Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Allsop Risk, Protection, and Substance Use in

Uploaded by

Carlos AngaritaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Allsop Risk, Protection, and Substance Use in

Uploaded by

Carlos AngaritaCopyright:

Available Formats

J. DRUG EDUCATION, Vol.

33(1), 91-105, 2003

RISK, PROTECTION, AND SUBSTANCE USE IN

ADOLESCENTS: A MULTI-SITE MODEL

ELIZABETH SALE, PH.D.

EMT Associates, Inc.

SOLEDAD SAMBRANO, PH.D.

Center for Substance Abuse Prevention

J. FRED SPRINGER, PH.D.

EMT Associates, Inc.

CHARLES W. TURNER, PH.D.

Caliber Associates

ABSTRACT

This article reports findings from a national longitudinal cross-site evaluation

of high-risk youth to clarify the relationships between risk and protective

factors and substance use. Using structural equation modeling, baseline data

on 10,473 youth between the ages of 9 and 18 in 48 high-risk communities

around the nation are analyzed. Youth were assessed on substance use

(cigarette, alcohol, and marijuana use), external risk factors including family,

school, peer and neighborhood influences, and individual risk and protective

factors including self-control, family connectedness, and school connectedness. Findings indicate strong direct relationships between peer and parental

substance use norms and substance use. Individual protective factors, particularly family and school connectedness were strong mediators of individual

substance use. These findings suggest that multi-dimensional prevention

programming stressing the fostering of conventional anti-substance use attitudes among parents and peers, the importance of parental supervision, and

development of strong connections between youth and their family, peers,

and school may be most effective in preventing and reducing substance use

patterns among high-risk youth.

91

2003, Baywood Publishing Co., Inc.

92

SALE ET AL.

Substance use is increasingly recognized as one of the nation=s most pervasive,

costly, and challenging health and social problems. The use of alcohol and drug

has resulted in tens of thousands of deaths annually, with the estimated costs of

alcohol and drug abuse in terms of lost earnings alone is estimated to be over $200

billion dollars annually [1]. Additionally, the use, and particularly the early use, of

tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, and other illicit drugs is intricately entwined with

serious personal and social problems, including school failure, crime, family

violence and abuse, and a host of additional social and personal problems that

constitute a continuing national tragedy.

Over the past 30 years, prevention researchers have produced substantial

evidence documenting the relationship between individual and environmental

factors and adolescent substance abuse. The prevention field has clearly recognized the power of social normsthe attitudes and behaviors perceived to prevail

in the social environmentas an influence on youth behavior. Peer influence

is an often-cited reason that youth begin to use substances. Research has established peer attitudes and behaviors as one of the strongest correlates of selfreported substance use [2-7]. Broader social norms (conveyed in the media and

in advertising) and conventional family norms [8] have also been identified

as correlates of use, or resistance to use, among youth. In this study, the peer and

parental substance use-related influences are referred to as substance use norms.

Another related branch of research has focused upon external risk and

protective factors, or those influences in the external environment that go beyond

the direct effects of peer and parental normative influences. These external risk

and protective factors include family dysfunction, poor maternal mental health,

poor family supervision, poor parenting practices, poor school climate, and

neighborhood disorder [9-16]. This body of research has shown that youth who

felt alienated from positive social institutions (family, school, and positive

peers) due to negative environmental factors were more likely to experiment with

alcohol and drugs than youth more connected to positive institutions. Youth

feeling detached from their families, school, and positive peers find deviant peers

with whom they can connect, and these associations lead to early experimentation

and later abuse of cigarettes, alcohol, and other drugs.

Research on the relationships between external risk and protective factors and

adolescent substance use shows strong evidence that negative influences in

children=s lives affect their use patterns. However, it fails to explain why youth

from the same risk environments have different substance use behaviors. Several

researchers have focused on the importance of individual protective factors in

differentiating youth who used and those who did not, while still acknowledging

the important role of external risk factors. Research using an individual protective

factor framework has shown that individuals with social competency, autonomy,

self-control and self-efficacy, were less likely to use than their counterparts

[17-20]. Much of the resiliency research has emphasized the importance of

attachments to positive influences, such as a caring and trusted adult [17]. Most

RISK, PROTECTION, AND SUBSTANCE USE /

93

often this bonding is seen as an individual (internal) attribute, the young persons

belief that this external connection is meaningful to him or her. Developing a sense

of connectedness [21] to meaningful segments of the environment that provide

and support positive opportunities is an important aspect of the internal protective orientation of young people in high-risk environments. Protective factors

therefore represent the influences, orientations, and behaviors in youths lives

that contribute to positive development and help prevent negative behaviors and

outcomes such as substance use.

AN INTEGRATED MODEL OF ADOLESCENT

SUBSTANCE USE

The analyses in the present study incorporate much of the thinking presented

above regarding the important relationship between substance use norms, external

and internal risk and protective factors, and adolescent substance use. Our model

asserts that external and internal risk and protective factors all influence substance

use behaviors, and that it is the interrelationship between the internal and external

factors, particularly connectedness of youth to their families and school, that are

most critical.

This theory-driven model draws heavily from the work of Hawkins and Weis

[12] and Kumpfer and Turner [22]. Hawkins and Weis=s social development

model was created in the context of juvenile delinquency, and asserted that

the most important units of socialization, family, schools, peers, and community, influence behavior sequentially [12, p. 73]. Juvenile delinquency could

be reduced not by focusing upon single influences, but by examining the ways in

which factors emerge and interact during the different stages in youngsters

lives [12, p. 74]. More specifically, they posit that opportunities for involvement

and interaction must exist in order for youth to become attached and committed

to conventional social values. This attachment and commitment leads to positive

associations with peers, which leads to nondelinquent behaviors. Kumpfer and

Turners social development model supports this research using a sample of

mainly Caucasian youth living in the State of Utah (n = 1800) [22]. This model

recognized the role of family, school, and peers in determining substance use

behaviors among adolescents, and expands the model to include academic

efficacy, or a measure of the degree to which youth felt effective in school. The

present analysis is a further expansion of this research, using a large sample of

high-risk youth.

METHOD

The study uses data from the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention (CSAP)

National Cross-Site Evaluation of High Risk Youth Programs. Forty-eight highrisk youth demonstration programs, funded by CSAP in 1994 and 1995, across the

94

SALE ET AL.

nation participated in the study. Programs were implemented to prevent and

reduce the use of alcohol and other drugs among at-risk youth. The evaluation

used a quasi-experimental comparison group design to study the more than 6,000

youth who participated in the 48 demonstration programs, comparing them with

more than 4,500 similar youth in the same communities who were not participating in the programs. The study used the CSAP National Youth Survey (CNYS),

a survey of external and internal risk and protective factors, substance use norms,

and substance use patterns. Youth were interviewed in person either during a

class session for school-based programs, or in an after-school or community

setting for community-based programs by evaluation staff. Testing occurred at

program entry, program completion, six months after program completion, and

18 months after program completion. Youth received small incentives of a $5 cash

equivalent at each administration for participating in the survey. Interviews took

between 45 minutes and 1 2 hours depending upon the age of the youth.

Participants

Youth in the study ranged between the ages of 9 and 18, and more than half

(57 percent) between 11 and 13 years of age when they entered the study. This

concentration of youth in pre- and early-adolescence shows that the prevention

programs in the study recruited and served predominantly children perceived to be

at a transition point that put them at particular risk for substance use initiation.

It also reflects the fact that youth in early adolescence are still relatively accessible

for organized programming because they do not yet drive, hold part-time jobs, or

have the freedom of movement available to older teens.

Because 19 (40 percent) of the programs included in the study targeted female

adolescents exclusively, there are many more females (66 percent) than males

(34 percent) in the total sample. Females are slightly older than males (mean

female age = 12.84; male = 12.76). The programs served a diversity of racial/

ethnic groups. More than 33 percent of the youth were African American and

around 25 percent were Hispanic. Of the remaining youth, approximately

10 percent were Native American, 10 percent were Asian/Pacific Islander, and

10 percent were White/non-Hispanic. Some programs used recruitment procedures that targeted special populations, adding diversity to the youth sample.

Most programs recruited youth from high-risk settings: schools, neighborhoods,

housing developments, or youth organizations. As an alternative, several programs based participant selection on a common individual behavioral or personal

attribute. Specifically, two programs served youth who had been placed in a secure

facility by court order; two programs targeted youth with disabilities (physical and

developmental/emotional); one program focused on young women with histories

of sexual abuse; and one program focused on youth in the foster care system.

Looking at the total pool of youth in the cross-site sample reporting substance use during the previous 30 days at baseline, the rate of use is low (Figure 1).

RISK, PROTECTION, AND SUBSTANCE USE /

95

Figure 1. Self-reported 30-day substance use at baseline:

percentage of study sample (N = 10,473).

The most frequently reported substances used were alcohol (18 percent),

cigarettes (18.5 percent), and marijuana (14 percent). Relatively few youth

reported recent use of drugs such as cocaine or crack, speed, tranquilizers, PCP,

and heroin.

The use rates of youth in the cross-site sample were higher than those of the

general population of youth. Table 1 compares use rates of 12- to 17-year olds in

the study sample with those of youth who participated in the 1998 National

Household Survey on Drug Abuse (NHSDA), a randomly sampled general population survey of persons 12-years-old and older [23]. Use rates for the NHSDA

population are considerably lower than those of the cross-site sample, indicating

the high-risk nature of the cross-site sample. Although the circumstances of the

NHSDA and the National Cross-Site Evaluation data collection are not identical,

this comparison suggests that the cross-site programs served youth who were at

higher risk for initiating use when young.

To profile the sample, a composite measure of 30-day substance use was

constructed. This composite measure includes the use of any one of three

substancestobacco, alcohol, or marijuanawithin the past 30 days. Figure 2

displays the percentage of youth who reported substance use by age and gender

using this composite measure of 30-day use.

Use rates for younger children remain low until around age 13 and then rise

rapidly until age 16 for females and age 17 for males. Use rates across the age

groups are consistently higher among males than females. Substance use among

96

SALE ET AL.

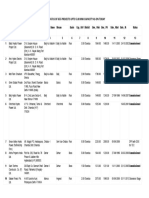

Table 1. Comparison of NHSDA and Cross-Site Substance Use

for 12- to 17-Year-Old Respondents

30-Day cigarette use

30-Day alcohol use

NHSDA

Cross-site

NHSDA

Cross-site

NHSDA

Cross-site

12-13

8.0%

9.6%

4.9%

11.3%

1.7%

5.8%

14-15

18.2%

32.8%

20.9%

31.2%

8.8%

27.0%

16-17

29.3%

51.4%

32.0%

46.4%

14.7%

46.7%

Age

30-Day marijuana use

Note: National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (NHSDA) sample size for 12- to

17-year-olds (n = 6,778); Cross-Site sample size for 12- to 17-year-olds (n = 7,245).

Figure 2. Self-reported 30-day substance use at baseline

by age and gender (N = 10,473).

females levels off at age 16 and remains somewhat constant through age 18. Males

in the 16- and 17-year-old age groups are mainly from very high-risk sites serving

incarcerated males, which accounts for the high use pattern in the age group at

program entry. The lower 30-day use rates for 18-year-olds suggests that the older

youth who participated in the study programs were individuals who were not as

involved in recent drug use as the younger high-school aged youth.

RISK, PROTECTION, AND SUBSTANCE USE /

97

Measures

The CSAP National Youth Survey designed for the Cross-Site Evaluation

included items in four domains: substance use norms, external risk and protection,

internal risk and protection, and individual substance use. Substance use norms

measures included: 1) perceived parental attitudes toward their child substance

use; 2) perceived peer attitudes toward substance use; and 3) peer substance use.

External risk and protective factor measures included: 1) family supervision;

2) family communication; 3) school prevention environment, or the degree to

which schools convey prevention messages about substance use and positive

personal development; 4) community protection environment, or the degree to

which the respondent participates in organized opportunities in the community;

and 5) neighborhood risk, or the perceptions of neighborhood substance use,

crimes against persons and property. Internal risk and protective factors include

measures of: 1) family bonding; 2) school bonding; 3) self-efficacy; and

4) self-control.

Pathways of Influence among Risk and

Protective Factors and Substance Use

These interrelationships between substance use, substance use norms, external

risk and protive factors, and internal risk and protective factors, were explored

with structural equation modeling using LISREL [24]. Specifically, the pathways

of influence among the risk and protective factors and substance use that were

supported in earlier research were examined using this large sample of high-risk

youth. The model presented in Figure 3 is based on data from the full (both

participant and comparison youth) study sample at baseline.1

The model includes the array of risk and protection factors and substance use

norms described in the previous section.2 The model fits the data well (CFI =

0.90),3 meeting the high standard for good model fit in these kinds of analyses.

Modeling Decisions

To produce a parsimonious model and improve statistical fit, the number of

factors included in the model was reduced analytically. The number of internal

1

Multigroup analyses contrasting treatment and comparison youth demonstrated no substantial

differences in model fit or path coefficients, justifying use of the combined sample of youth at high risk.

All exogenous variables were allowed to correlate. For each latent construct, the items demonstrating

the strongest factor loadings were fixed to 1.0 to scale the latent factors [25].

2

The width of each arrow shaft indicates the strength of the association between the individual

protective factor and substance use; i.e., the degree to which higher protection on the factor relates to

less use. Wider arrows shafts are indicative of stronger relationships.

3

The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) statistic measures the goodness of fit. Models with indices of 0.90

or more are considered to be strong-fitting models.

98

SALE ET AL.

Figure 3. Structural equation model of risk and protection factors

and substance use among high-risk youth (N = 10,473).

factors was reduced to three: school connectedness, family connectedness, and

self-control. School connectedness, a newly constructed latent variable, is

composed of the school bonding and self-efficacy items, forming a single measure

that represents the importance of the school as a forum in which youth can realize

self-efficacy. Family connectedness is a latent variable that combines the original

family bonding measure with the family communication measure. The new

measure represents the importance of family as a forum for safe and supportive

communications during the developmental years. Self-control is maintained in

its original form.

In the external risk and protective factors domain, family supervision, school

prevention environment, community protection environment, and neighborhood

risk were included in the model. School performance, a factor combining selfreported measures of grades in school and school attendance, was added to the

model as a latent variable, mediating between school connectedness and peer

substance use. In the substance-use norm domain (parent and peer attitudes and

per use), the model asserts that substance-use norm measures mediate between

external and internal risk and protective factors and substance use. More specifically, the positioning of the peer norm measures (peer attitudes, peer substance

use) implies that the creation of positive friendship groups is an important

RISK, PROTECTION, AND SUBSTANCE USE /

99

consequence of family and school influences. Youth are involved in positive

peer groups because their families and schools have stressed the importance of

developing positive relationships with peers. The positioning of the parent norm

measure (parental attitudes) implies that family connectedness and family supervision create an environment in which parents= messages carry weight.

Interpreting the Model

The model in Figure 3 supports the relationship between risk and protection

factors and substance use, particularly the roles of family and school. Family

connectedness is a key to the substantial path of influence on substance use shown

in the model. When family connectedness is high, family supervision and parental

attitudes exert strong influences on peer associations and substance use. When

family connectedness is high and parental supervision is high, parental attitudes

carry particular weight. The substantial direct negative effect (coefficient = 0.40)

on substance use indicates that parental attitudes matter in the connected

familyeven when those attitudes are at odds with peer attitudes and behaviors.

School connectedness is also a crucial link in the internal risk and protection path.

Family connectedness and self-control contribute to school connectedness, which

relates to school performance, peer substance use, and ultimately personal

substance use. The measure of school performance (self-reported grades and

attendance) provides an important link in this path. Youth doing well in school

tend to associate with non-using peers and use less. In the community domain,

neighborhood risk is associated with peer substance use as an influence on

personal use, reflecting the importance of social environment in shaping youth

behaviors. Youth living in more dysfunctional neighborhoods are more likely to

associate with substance using peers and use themselves. The model clearly

supports the interactive nature of protective influencesinternal, external, and

normativeagainst substance use.

Pathways of Influence among Males and Females

The model shown in Figure 4 shows the pathway of influence according to

gender. (Coefficients in parentheses are for females.)4 There is a strong fit for

both males and females, and the overall statistical fit of the model is good

(CFI = 0.90). All of the hypothesized paths hold for both gender groups.

Some interesting implications emerge from the few gender differences shown

in the model. Significant differences in the strength of the structural paths emerged

along four paths in the model. School connectedness is a stronger predictor of

reported school performance (grades and school attendance) for females (0.43)

4

All item and factor variances were estimated freely between the group, with equality constraints

placed on the factor loadings and factor correlations.

100

SALE ET AL.

Figure 4. Structural equation model for males and females

(males, N = 3,596; females, N = 6,941).

than for males (0.13), suggesting that for females than for males, bonding to school

influences their academic performance. Parental attitudes toward substance use

are slightly more strongly related to personal use for females (0.42) than for

males (0.37). This suggests that females are less likely than males to use if

their parents clearly disapprove of their use. Both paths from neighborhood

risk to peer substance use to the subject=s own substance use are slightly stronger

for males (0.31 and 0.56) than females (0.14 and 0.48). Males are more

influenced by peer and community factors than females. However, these differences are minor within the overall similarity of the paths to substance use for

both genders.

Pathways of Influence among Younger and Older Youth

The models were also analyzed according to the age of youth in the study.

The sample was divided in two groups: 9 to 11 year olds and 12 to 18 year olds.

The unconstrained model fit the data well (CFI = 0.92). (Coefficients in parentheses are for the older youth.) The model is strong for both younger and older

youth.

Several major age-related differences emerge in the model. The first is the

importance of family factors for older youth. Family supervision and parental

RISK, PROTECTION, AND SUBSTANCE USE /

101

Figure 5. Structural equation model for younger and older youth

(younger (9-11), N = 2,879; older (12-18), N = 7,566).

attitudes are stronger predictors of substance use behavior in youth 12 years and

older than they are for preteens. Some of this difference may be attributed to

reduced variation in the younger group, where positive orientation toward family

is higher in general. Nevertheless, the data indicate that the family continues to

play a critical protective role as youth develop through adolescencedespite the

fact that teens report a decline in family supervision and family connectedness as

they grow older (see Figures 3 and 4).

Second, peers influence older youth more than younger youth. Peer attitudes

and perceptions of peer use are stronger predictors of substance use among older

youth than they are for those younger than 12. This reflects the developing

sensitivity to social perceptions that begins in early adolescence and continues

into adulthood. Third, the path from school connectedness to school performance

is stronger for younger youth than for the older group. This suggests that school

plays a critical role in influencing positive behaviors that may lead to prevention of or reductions in substance use among younger youth. Fourth, school

performance is a stronger predictor of substance use behavior in older youth

than in younger youth. For students 12 and older, the model suggests that poor

grades are associated with substance-using peers and personal substance use.

In sum, school performance, parental supervision, parental attitudes, and peer

attitudes influence youths decisions regarding personal use, especially among

older youth.

102

SALE ET AL.

Model Summary

In summary, the model of risk and protection factors for substance use among

high-risk youth is robust. It is based on a large sample of at-risk youth, and it

applies to females and males, and younger and older youth. The model emphasizes

the critical importance of family, peers, and individual protective factors for

buffering youth from substance use. More importantly, it suggests the interdependence of these domains. The key to prevention is not to make youth

insensitive to their social environment, but to ensure that they are strongly

connected to positive, healthy environments. Given the stability of the model

across these important population subgroups, practitioners can use it to address

important questions about which risk and protective factors prevention programs

should be targeting. By reducing to a manageable number the important predictors of substance use, the model should help practitioners focus their resources

efficiently to improve program outcomes.

DISCUSSION

The CSAP National Cross-Site Evaluation of High-Risk Youth Programs has

created an excellent opportunity to expand knowledge about risk and protective

factors and substance use among youth at high risk. The models presented here

bring additional coherence and focus to the ways in which risk, protective, and

normative factors influence substance use among youth. Expanding on prior

research, these models show the indirect and direct relationships among individual, family, peer, school, and community factors using a large sample of

high-risk youth. The model is relatively stable across age and gender. There is

some evidence that family and school influences are more important for females

than males and that peer and neighborhood risk influences are stronger for males.

The models also show the important role that family plays in adolescent substance

use, especially for older youth.

By specifying plausible pathways within and between external, internal, and

normative risk factors and substance use, the model adds detail to understanding why adolescents use. In terms of internal risk and protection, the

analyses have important research implications. The previous literature on

internal risk and protection has proposed numerous attitudes, orientations, and

personal competencies as critical factors in youths use of substances. The

result has been confusion. This analysis suggests a much simpler structure of

important issues. Factors that build connectedness with the external environment (family and school connectedness) are critical deterrents to adolescent

substance use.

The analyses also point to the importance of school as a forum for changing

substance use patterns. Both school connectedness and school performance

RISK, PROTECTION, AND SUBSTANCE USE /

103

show strong associations with individual substance use. Furthermore, this study

shows the strong association between peers and individual substance use. The

relationship between peer and individual substance use is the strongest among

the factors in the model. This finding is supported among males and females, as

well as older and younger youth. Peer effects also serve as a powerful mediator

between individual, family, school, and community factors and individual substance use. Finally, by highlighting the importance of the family and the school,

the model suggests that youth develop important personal competencies (such

as cooperativeness, a positive view of the future, a belief in self, and a feeling of

personal efficacy) through positive orientations to, and interactions with, central

social settings.

These analyses have direct implications for prevention policy and practice.

They confirm the importance of comprehensive prevention that addresses the

range of environmental factors as well as the individual orientations and behaviors

of the youth themselves. The central implication for prevention is the need to build

connections to positive and meaningful social environments for youth. Though

important, just changing the environment, or just changing individual orientations,

is not enough. Protection and positive development requires connection between

the two. Building and supporting these connections is a central challenge to

prevention and a positive promise to youth.

REFERENCES

1. H. Harwood, Updating Estimates of the Economic Costs of Alcohol Abuse in the United

States: Estimates, Update Methods and Data, report prepared by the Lewin Group

for the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2000.

2. R. L. Akers, Deviant Behavior: A Social Learning Approach, Wadsworth, Belmont,

California, 1977.

3. D. Elliott, D. Huizinga, and S. S. Ageton, Explaining Delinquency and Drug Use,

Behavioral Research Institute, Boulder, Report No. 21, 1982.

4. D. S. Ford, Factors Related to the Anticipated Use of Drugs by Urban Junior High

School Students, Journal of Drug Education, 13:2, pp. 187-197, 1983.

5. S. W. Fors and D. G. Rojek, The Social and Demographic Correlates of Adolescent

Drug Use Patterns, Journal of Drug Education, 13:3, pp. 205-222, 1983.

6. B. Foster, Upper Middle Class Adolescents Drug Use: Patterns and Factors, Advances

in Alcohol and Substance Abuse, 4:2, pp. 27-36, 1984.

7. E. E. Oetting and F. Beauvais, Peer Cluster Theory: Drugs and the Adolescent, Journal

of Counseling and Development, 65, pp. 17-22, 1986.

8. M. D. Newcomb, G. J. Huba, and P. M. Bentler, Risk Factors for Drug Use among

Adolescents: Concurrent and Longitudinal Analyses, American Journal of Public

Health, 776, pp. 525-531, 1986.

9. D. Baumrind, Familial Antecedents of Adolescent Drug Use: A Developmental

Perspective, in National Institute on Drug Abuse Research: Monograph Series,

104

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

SALE ET AL.

C. L. A. Jones and R. J. Battjes (eds.), National Institute on Drug Abuse, pp. 13-44,

1985.

J. Brook, D. Brook, A. Gordon, M. Whiteman, and P. Cohen, The Psychosocial

Etiology of Adolescent Drug Use: A Family Interactional Approach, Genetic, Social

and General Psychology Monographs, 116:Whole No. 2, 1990.

D. Hawkins, R. Catalano, and J. Miller, Risk and Protective Factors for Alcohol and

Other Problems in Adolescence and Early Adulthood: Implications for Substance

Abuse Problems, Psychological Bulletin, 112, pp. 64-105, 1992.

J. D. Hawkins and J. G. Weiss, The Social Development Model: An Integrated

Approach to Delinquency Prevention, Journal of Primary Prevention, 6:2, pp. 73-97,

1985.

G. M. Smith and C. P. Fogg, Psychological Predictors of Early Use, Late Use, and

Nonuse of Marijuana among Teenage Students, in Longitudinal Research on Drug

Use: Empirical Findings and Methodological Issues, D. B. Kandel (ed.), pp. 101-113,

1978.

J. A. Stein, M. D. Newcomb, and P. M. Bentler, An 8-Year Study of Multiple

Influences on Drug Use and Drug Use Consequences, Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 53, pp. 1094-1105, 1987.

J. A. Stein, M. D. Newcomb, and P. M. Bentler, Stability and Change in Personality:

A Longitudinal Study from Early Adolescence to Young Adulthood, Journal of

Research in Personality, 20:3, 1986.

J. A. Stein, M. D. Newcomb, and P. M. Bentler, Personality and Drug Use: Reciprocal

Effects Across Four Years, Personality & Individual Differences, 1987.

B. Benard, Fostering Resiliency in Kids: Protective Factors in the Family, School,

and Community, Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory/Western Regional

Center for Drug-Free Schools and Communities, Portland, Oregon, 1991.

H. B. Kaplan, S. S. Martin, and C. Robbins, Application of a General Theory of Deviant

Behavior: Self-Derogation and Adolescent Drug Use, Journal of Health and Social

Behavior, 23, pp. 274-294, 1982.

H. B. Kaplan, S. S. Martin, and C. Robbins, Pathways to Adolescent Drug Use:

Self-Derogation, Peer Influence, Weakening of Social Controls, and Early Substance

Use, Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 25, pp. 270-289, 1984.

E. Werner and R. Smith, Vulnerable But Invincible: A Longitudinal Study of Resilient

Children and Youth, Adams, Bannister, and Cox, New York, 1982.

M. D. Resnick, P. S. Bearman, R. W. Blum, K. E. Bauman, K. M. Harris, J. Jones,

J. Tabor, T. Beunning, R. Sieving, M. Shew, M. Ireland, L. Bearinger, and J. R. Udry,

Protecting Adolescents from Harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study

on Adolescent Health, Journal of the American Medical Association, 278, pp. 823-832,

1997.

K. L. Kumpfer and C. W. Turner, The Social Ecology Model of Adolescent Substance

Use: Implications for Prevention, The International Journal of Addictions, 25:4A,

pp. 435-463, 1991.

SAMHSA/OAS, National Household Survey on Drug Abuse Population Estimates

1998, Office of Applied Studies, Rockville, Maryland, 1998.

K. G. Joreskog and D. Sorbom, Lisrel 8: New Statistical Features, SSI, Chicago,

1999.

RISK, PROTECTION, AND SUBSTANCE USE /

105

25. B. Byrne, Structural Equation Modeling with EQS and EQS/Windows: Basic

Concepts, Applications and Programming, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks,

1994.

Direct reprint requests to:

Elizabeth Sale, Ph.D.

Senior Research Associate

EMT Associates, Inc.

2nd Floor

208 North Euclid

St. Louis, MO 63108-1602

e-mail: esale@emt.org

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- JDDocument19 pagesJDJuan Carlo CastanedaNo ratings yet

- Epq JDocument4 pagesEpq JMatilde CaraballoNo ratings yet

- Protein Synthesis: Class Notes NotesDocument2 pagesProtein Synthesis: Class Notes NotesDale HardingNo ratings yet

- Erp Software Internship Report of Union GroupDocument66 pagesErp Software Internship Report of Union GroupMOHAMMAD MOHSINNo ratings yet

- Oxfordhb 9780199731763 e 13Document44 pagesOxfordhb 9780199731763 e 13florinaNo ratings yet

- Relatório ESG Air GalpDocument469 pagesRelatório ESG Air GalpIngrid Camilo dos SantosNo ratings yet

- HRM Unit 2Document69 pagesHRM Unit 2ranjan_prashant52No ratings yet

- Commissioning GuideDocument78 pagesCommissioning GuideNabilBouabanaNo ratings yet

- APP Eciation: Joven Deloma Btte - Fms B1 Sir. Decederio GaganteDocument5 pagesAPP Eciation: Joven Deloma Btte - Fms B1 Sir. Decederio GaganteJanjan ToscanoNo ratings yet

- Httpswww.ceec.Edu.twfilesfile Pool10j07580923432342090202 97指考英文試卷 PDFDocument8 pagesHttpswww.ceec.Edu.twfilesfile Pool10j07580923432342090202 97指考英文試卷 PDFAurora ZengNo ratings yet

- The RF Line: Semiconductor Technical DataDocument4 pagesThe RF Line: Semiconductor Technical DataJuan David Manrique GuerraNo ratings yet

- BAFINAR - Midterm Draft (R) PDFDocument11 pagesBAFINAR - Midterm Draft (R) PDFHazel Iris Caguingin100% (1)

- DepEd K to 12 Awards PolicyDocument29 pagesDepEd K to 12 Awards PolicyAstraea Knight100% (1)

- List/Status of 655 Projects Upto 5.00 MW Capacity As On TodayDocument45 pagesList/Status of 655 Projects Upto 5.00 MW Capacity As On Todayganvaqqqzz21No ratings yet

- Underground Rock Music and Democratization in IndonesiaDocument6 pagesUnderground Rock Music and Democratization in IndonesiaAnonymous LyxcVoNo ratings yet

- History of Downtown San Diego - TimelineDocument3 pagesHistory of Downtown San Diego - Timelineapi-671103457No ratings yet

- Unitrain I Overview enDocument1 pageUnitrain I Overview enDragoi MihaiNo ratings yet

- Exam SE UZDocument2 pagesExam SE UZLovemore kabbyNo ratings yet

- El Rol Del Fonoaudiólogo Como Agente de Cambio Social (Segundo Borrador)Document11 pagesEl Rol Del Fonoaudiólogo Como Agente de Cambio Social (Segundo Borrador)Jorge Nicolás Silva Flores100% (1)

- The Hittite Name For GarlicDocument5 pagesThe Hittite Name For GarlictarnawtNo ratings yet

- Corporate Office Design GuideDocument23 pagesCorporate Office Design GuideAshfaque SalzNo ratings yet

- Master Your FinancesDocument15 pagesMaster Your FinancesBrendan GirdwoodNo ratings yet

- CVA: Health Education PlanDocument4 pagesCVA: Health Education Plandanluki100% (3)

- NDA Template Non Disclosure Non Circumvent No Company NameDocument9 pagesNDA Template Non Disclosure Non Circumvent No Company NamepvorsterNo ratings yet

- Scantype NNPC AdvertDocument3 pagesScantype NNPC AdvertAdeshola FunmilayoNo ratings yet

- Module 3 - Risk Based Inspection (RBI) Based On API and ASMEDocument4 pagesModule 3 - Risk Based Inspection (RBI) Based On API and ASMEAgustin A.No ratings yet

- A Christmas Carol AdaptationDocument9 pagesA Christmas Carol AdaptationTockington Manor SchoolNo ratings yet

- TDS Tetrapur 100 (12-05-2014) enDocument2 pagesTDS Tetrapur 100 (12-05-2014) enCosmin MușatNo ratings yet

- Commercial Contractor Exam Study GuideDocument7 pagesCommercial Contractor Exam Study Guidejclark13010No ratings yet

- Amazfit Bip 5 Manual enDocument30 pagesAmazfit Bip 5 Manual enJohn WalesNo ratings yet