Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Musical Issue

Uploaded by

TsogtsaikhanEnerelCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Musical Issue

Uploaded by

TsogtsaikhanEnerelCopyright:

Available Formats

659250

research-article2016

JRMXXX10.1177/0022429416659250Journal of Research in Music EducationRicherme

Original Research Article

Measuring Music Education:

A Philosophical Investigation

of the Model Cornerstone

Assessments

Journal of Research in Music Education

2016, Vol. 64(3) 274293

National Association for

Music Education 2016

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0022429416659250

jrme.sagepub.com

Lauren Kapalka Richerme1

Abstract

Despite substantial attention to measurement and assessment in contemporary

education and music education policy and practice, the process of measurement has

gone largely undiscussed in music education philosophy. Using the work of physicist

and philosopher Karen Barad, in this philosophical inquiry, I investigated the nature

of measurement in music education while concurrently exploring the assumptions

underlying documents related to the proposed music Model Cornerstone Assessments.

First, Barads concepts of reflection and diffraction reveal the false assumption that

measurement captures rather than alters and produces musical experiences. Second,

measurement apparatuses are explained as boundary-making practices. Third, the

limits of measurement apparatuses are explored through Barads assertions about

experimental inclusions and exclusions and Lyotards concept of the differend,

and these limits are used to problematize the ambitious, value-laden discourse of

documents related to the music Model Cornerstone Assessments. Finally, through

Barads concept of intra-action, measurement is reinterpreted as a process through

which teacher and student emerge. Music education policymakers, teachers, and

students might adopt language emphasizing the intra-active nature of measurement

and empower themselves to critique and reimagine existing measurement apparatuses

and their measurement and assessment practices.

Keywords

measurement, assessment, philosophy, policy, music education

1Indiana

University Jacobs School of Music, Bloomington, IN, USA

Corresponding Author:

Lauren Kapalka Richerme, Music Education Department, Indiana University Jacobs School of Music,

1201 E 3rd St., Bloomington, IN 47405, USA.

Email: lkricher@indiana.edu

Richerme

275

Contemporary education policies in North America and beyond are entrenched in the

language of measurement and assessment (e.g., Darling-Hammond, Amrein-Beardsley,

Haertel, & Rothstein, 2012; Horsley, 2014; Perrine, 2013). In the United States, while

individual states began taking action toward educational accountability in the 1960s

and 1970s (Mehta, 2013), the advent of the No Child Left Behind Act (2002) unified

assessment collecting and reporting procedures. More recently, in order for states to

receive a waiver granting flexibility from the requirements set by No Child Left

Behind, policymakers must adopt annual, statewide, aligned, high-quality assessments and include student growth as a significant factor in teacher evaluations

(U.S. Department of Education, 2012, p. 1). As a result of this policy and programs

such as Race to the Top (American Recovery and Reinvestment, 2009), the majority

of states have adopted the Common Core State Standards, which enable the development and implementation of common comprehensive assessment systems to measure

student performance annually that will replace existing state testing systems

(Common Core, 2015, p. 2). While states such as Indiana and Oklahoma have withdrawn from the Common Core State Standards, policymakers have replaced them with

their own statewide standards and assessments. Despite growing parental opposition

to student testing (e.g., OConner, 2014; Sanchez, 2015), large-scale student assessment will likely form an integral part of American education policies for the foreseeable future.

The language of measurement and assessment has also permeated music education discourse and action (e.g., Arostegui, 2003; Scott, 2012; Shuler, 2012;

Wesolowski, 2012). Drawing inspiration from the Common Core State Standards,

music educators authoring the 2014 National Core Arts Standards conceived of

these standards in integration with new Model Cornerstone Assessments (State

Education Agency Directors of Arts Education, 2014). The authors of the current

in-progress drafts of the Model Cornerstone Assessments intend them to provide

formative and summative means to measure student achievement of performance

standards in the National Core Music Standards (National Association for Music

Education, 2015a, p. 1). The writers of documents associated with drafts of the

Model Cornerstone Assessments note the assessments voluntary nature, and thus

they serve as suggestions rather than as policy mandates. However, the authors of

the Conceptual Framework for the National Core Arts Standards express hope that

these assessments will focus the great majority of classroom- and district-level

assessments around rich performance tasks that demand transfer (State Education

Agency Directors of Arts Education, 2014, p. 16).1 The music Model Cornerstone

Assessments website indicates the current pilot testing of the creating, performing,

and responding assessments for ensembles and for grades two, five, and eight of the

proficient, accomplished, and advanced assessments for technology and composition-theory and of the proficient assessment for guitar/keyboard/harmonizing

instruments (National Association for Music Education, 2016). Despite substantial

attention to measurement and assessment in contemporary education and music education policy and practice, the process of measurement has gone largely undiscussed

in music education philosophy.

276

Journal of Research in Music Education 64(3)

Music education does not always necessitate formal measurements and assessments. Indeed, music teaching and learning frequently occur through an apprenticeship model that utilizes hands-on training and informal assessment. This philosophical

inquiry focuses on contemporary American school-based K12 music education and

rests on the premise that the current political climate necessitates some amount of

student measurement and assessment.

Philosophical inquiries investigate specifically philosophical questions, including

those related to ontology or the nature of being (Jorgensen, 1992). Through such

examinations, philosophers question assumptions underlying thinking and practice

(Bowman, 1998; Froehlich & Frierson-Campbell, 2012; Phelps, Ferrara, & Goolsby,

1993). The purpose of this philosophical inquiry is to investigate the nature of measurement in music education while concurrently exploring the assumptions underlying

documents related to the proposed music Model Cornerstone Assessments. These

assessments, which necessitate the process of measurement, were chosen because of

their potentially wide-reaching implications, but the issues and questions raised in this

inquiry could apply to other measurements and assessments.2

Theoretical Framework

This investigation draws on the work of Karen Barad, a contemporary philosopher

who also holds a degree in theoretical particle physics. Her most cited work, Meeting

the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and

Meaning (Barad, 2007), has received marked attention from writers in fields ranging

from media studies (e.g., Deuze, 2012) to economics (e.g., Orlikowski, 2015) to education philosophy (e.g., Fenwick & Edwards, 2010; Taguchi, 2010; Wegerif, 2013).

Since the current emphasis on measurement in education relies on a worldview that

foregrounds scientific verification, Barads physics background allows her to provide

a unique philosophical perspective on the process and implications of measurement.

Although measurement within a scientific laboratory clearly looks different than

measurement within educational settings, the same general set of procedures governs

both practices. Writing about measurement in education and psychology, Thorndike

and Thorndike-Christ (2010) explain:

Measurement in any field involves three common steps: (1) identifying and defining the

quality or the attribute that is to be measured, (2) determining the set of operations by

which the attribute may be isolated and displayed for observation, and (3) establishing a

set of procedures or definitions for translating our observations into quantitative

statements of degree or amount. (p. 10)

These steps occur regardless of whether one is measuring qualities of a particle in

a physics experiment or aspects of student learning in a music classroom; while the

what may change, the overarching how does not. Thus, Barads writings about

measuring quantum phenomena can inform music educators understandings of their

own measurement practices.

Richerme

277

Measurement is distinct from assessment. Consistent with Thorndike and

Thorndike-Christ (2010), Payne (2003) explains that in education, Measurement is

concerned with the systematic collection, quantification, and ordering of information.

It implies both the process or quantification, and the result (p. 7). In contrast, educational assessment is the interpretive integration of application tasks (procedures) to

collect objectives-relevant information for educational decision making and communication about the impact of the teaching-learning process (Payne, 2003, p. 9). In

other words, measurement involves gathering data and assigning numbers to qualities

such as attributes or behaviors, while assessment encompasses making inferences and

value judgments about the collected information (e.g., Miller, Linn, & Gronlund,

2009; Reynolds, Livingston, & Willson, 2009). Put simply, Assessment =

Measurement + Evaluation (Payne, 2003, p. 9).

Measurement is central to the Model Cornerstone Assessments. Authors of related

documents explain that they aimed to develop common tools to measure student

learning (Common Arts Assessment Initiative, 2014, p. 1) and that the Model

Cornerstone Assessments would show how student learning can be measured

through rich performance tasks (State Education Agency Directors of Arts Education,

2014, p. 8). The term measure also appears in all current versions of the Model

Cornerstone Assessments; each of the 23 assessment drafts begins with the opening

line Model Cornerstone Assessments (MCAs) in music are tasks that provide formative and summative means to measure student achievement of performance standards

in the National Core Music Standards (e.g., National Association for Music

Education, 2015a, p. 2; 2015c, p. 2).3 While the Model Cornerstone Assessments

ultimately enable teachers to assess students by interpreting and communicating

the information they collect, their authors, in alignment with definitions in education

literature, indicate that the process of measurement serves as a necessary precursor to

such action.

Because Barads (2007) interest lies in the ways in which individual scientists

engage with quantum phenomena, she writes almost exclusively about the process

of measurement rather than about how the experimenter or wider scientific community assesses those measurements. Yet, since Barads larger philosophical project involves drawing on contemporary scientific measurement practices to

reconceptualize existence, applying her writings to practices beyond measurement

is consistent with her work. As such, this philosophical inquiry focuses on the

process of measurement while at times extending Barads ideas to aspects of

assessment.

First, in this philosophical inquiry I explore Barads (2007) concepts of reflection

and diffraction and use them as a framework through which to analyze documents

related to the Model Cornerstone Assessments. Second, I explain Barads writings

about measurement apparatuses and apply them to the Model Cornerstone Assessments.

Third, I investigate the limits of measurement apparatuses. Fourth, I examine the relationship between teacher and student in the measurement process using Barads concept of intra-action. Finally, I posit four suggestions for music education policy and

practice.

278

Journal of Research in Music Education 64(3)

Reflection and Diffraction

Barad (2007) draws on aspects of the physics phenomena of reflection and diffraction

to distinguish between reflective and diffractive methodologies. She explains that

reflection involves mirror images, writing, To mirror something is to provide an

accurate image or representation that faithfully copies that which is being mirrored

(p. 86). In reflection, objects are held at a distance, and a clear boundary exists

between observer and object. Researchers relying on a reflective methodology consider themselves and their measurements independent from the phenomena under

their investigation. In contrast, diffractive patterns necessitate marking differences

from within and as part of an entangled state (p. 89). In diffraction, observer and

object are not fixed but emerging and contingent on each other.4 Researchers relying

on a diffractive methodology consider themselves part of and evolving in integration

with the phenomena they measure.

Writers of documents associated with the music Model Cornerstone Assessments

imply that those adopting the assessments will use a reflective rather than a diffractive

methodology. For example, authors state that teachers can use the pilot and final versions of the assessments to monitor and improve student learning in the arts

(Common Arts Assessment Initiative, 2014, p. 1). Similarly, the writers of the

Conceptual Framework that accompanies the National Core Arts Standards assert that

teachers can capture student work based on the model cornerstone assessments

(State Education Agency Directors of Arts Education, 2014, p. 6). Words like monitor

and capture insinuate a distanced observer distinct from students and their work. Just

as one can monitor a room from a hidden camera or capture a candid photograph, these

authors imply that a teacher can measure student growth without altering students

learning processes or musical experiences.

Barad (2007) explains the false assumptions underlying reflective methodologies,

writing, Scientific practices may more adequately be understood as a matter of intervening rather than representing (p. 54). By isolating certain qualities and quantities,

quantum physics experiments do not just represent existing conditions, they change

the phenomena under investigation. This does not mean that measurement is not reproducible; reproducibility results from adherence to specific procedures of measurement

(Barad, 2007). In other words, scientists control their experimental conditions so that

they intervene with phenomena in the same manner each time, thus allowing them to

replicate findings.

Through the act of measuring, scientists and music educators alike alter the

phenomena under investigation. Take, for example, the part of the second-grade

creating Model Cornerstone Assessment that involves improvising two four-beat

long rhythmic answers to a teachers rhythmic prompts (National Association for

Music Education, 2015a). During the task, the teacher measures student learning and

then assesses it with a rubric, and the students fill out a self-assessment sheet, which

includes statements such as I kept a steady beat and My answers were expressive

followed by the choices of yes with a smiling face, no with a frowning face, and sometimes with a neutral face (National Association for Music Education, 2015a, p. 7).

Richerme

279

Consider how a group of second graders might respond in the following three

scenarios: The students improvise without the teacher using the Model Cornerstone

Assessment; the teacher explains the Model Cornerstone Assessment and then the students improvise; the students improvise and then the teacher explains that he or she

just measured and assessed their improvisations using the Model Cornerstone

Assessment.5 Would a student in each context have a different musical experience? If

so, why?

In all three scenarios, decisions the teacher makes regarding content and pedagogy

will affect students experiences. For instance, while the second-grade students improvise, the music educator may focus their attention on specific musical concepts or on

other aspects of the experience, such as their emotions or bodies. These decisions

affect students immediate musical experiences as well as their future musical engagements; students who practice using dynamics while improvising will likely attend to

that musical quality differently in subsequent music performing, listening, and creating experiences. Yet, in the first and third scenarios, when students do not anticipate

that the teacher will measure their improvisations, the quality and intensity of students

attention and their accompanying emotions will likely contrast those of students made

aware of forthcoming measurements.

In the second scenario, in which, as suggested in the assessments instructions, the

teacher makes the students aware of the measurement before the improvisation, the

students approach the musical endeavor with the prospect of measurement. Secondgrade students who know that they and their teacher will determine to what extent they

have kept a steady beat have more reason to focus their full attention on that quality

than those who do not anticipate that a teacher will measure their improvisations. In

other words, students respond differently to the direction keep a steady beat than to

the statement Im going to measure the steadiness of your beat. Additionally, students may experience nervousness, excitement, or other feelings before, during, and

after the measurement. While any musical experience can arouse such emotions, the

process of measurement has the potential to alter the type, quality, and strength of

students emotional experiences.

Students may also change when teachers share their assessment of the measured

performance with them.6 Such action can affect how students in this scenario remember the musical experience. For example, imagine a student who circled the yes and

smiling face next to the statement I kept a steady beat only to have the teacher indicate that he or she did not keep a steady beat. The student, who may have felt happy

after the initial musical experience, may now look back on the event with sadness.

Similarly, in the third scenario, in which the teacher makes the students aware of the

measurement only after the musical experience, while the students will not feel the

embodied-emotional reactions or cognitive intensification associated with an impending measurement, their perceptions of and feelings about the musical experience will

likely change as they reflect on their actions and receive input from their teacher. In

short, the prospect of measurement can affect ones anticipation of a musical experience, the process of measurement can affect ones engagement during a musical experience, and the results of past measurements can affect ones memories of a musical

280

Journal of Research in Music Education 64(3)

experience. While an individual students reactions to any form of measurement

depend on a variety of factors, ranging from prior experiences to the current classroom

environment to his or her general disposition, these scenarios reveal that measurement

does not just monitor or capture students music-making and learning but fundamentally changes it.

Because students cannot undo the alterations resulting from their learning being

measured and assessed, those processes will affect their future musical engagements.

In other words, experiencing measurement and assessment contributes to ones changing musical self. Imagine that the teacher in the second and third aforementioned scenarios then repeats the improvisation exercise without any measurement. Since the

students have practiced intensely focusing their attention on the musical elements

named in the measurement and assessment processes, such practices will influence

their subsequent musical endeavors. For example, a student who circled the no and

frowning face next to the statement I used interesting rhythms cannot help but bring

that information to subsequent musical endeavors.

Measurement and assessment do not just change existing experiences, they constitute ones evolving experiences. Randall Allsup (2015) writes, We are more than the

music we make; we are simultaneously made and remade by the music we make

(p. 8). The experience of hearing a specific genre of music or undertaking a certain

musical practice contributes to ones evolving musical self and interfaces with all

future musical endeavors. Likewise, while students are more than measurement

results, they are made and remade by measurements and assessments.

Although measurements and assessments can leave students upset or unmotivated,

they can also positively impact their musical development. Students who intensely

direct their attention toward keeping a study beat or the complexity of their rhythmic

improvisations can build on those experiences in their future musical endeavors. In

addition to propagating false assumptions about the nature of measurement, language

that neglects the role of measurement and subsequently assessment in producing an

individuals continually changing musical experiences may cause teachers and students

to miss the potentially beneficial ways in which these processes can enhance learning.

If measurement in part constitutes students changing musical and educational experiences and selves, then measurement apparatuses deserve significant attention.

Measurement Apparatuses

The act of measuring necessitates a specific measurement apparatus that forms boundaries in order to function. Barad (2007) explains, Apparatuses are not mere observing

instruments but boundary-drawing practicesspecific material (re)configurations of

the worldwhich come to matter (p. 140). This statement has two important implications. First, the boundaries drawn by measurement apparatuses do not preexist those

apparatuses. For example, the authors of the music Model Cornerstone Assessments

create boundaries between the practices of creating, performing, and responding as well as between types of musical engagement such as ensembles, composition-theory, technology, and guitar/keyboard/harmonizing instruments (National

Richerme

281

Association for Music Education, 2016). Within each measurement apparatus,7 the

authors distinguish further boundaries between qualities such as expressive and

formal, thus demarcating limits between concepts associated with those labels (e.g.,

National Association for Music Education, 2015b, p. 7). The boundaries between and

within these practices are not inevitable or universal but temporary configurations

determined by the apparatuses creators. Likewise, teachers and students adapting the

Model Cornerstone Assessments to meet their local needs inevitably draw new boundaries between musical practices and qualities.

Second, boundaries are practices that those using measurement apparatuses sustain and reinforce. When second-grade students measure and assess their learning by

filling out the self-assessment sheets following their rhythmic improvisations, they

reproduce the boundaries between the musical concepts enumerated on their sheets.

The boundaries between musical concepts and practices exist in and through the act of

making informal and formal measurements. Teachers also produce boundaries through

practices beyond measurement and assessment; actions such as selecting content and

emphasizing and labeling certain terms all contribute to divides between different

types of musical practices and concepts as well as between school musical practices

and music-making taking place elsewhere in society. These boundary-producing practices exist in integration with those created and reinforced through measurement and

assessment procedures.

It is important to note that measurement need not involve a physical apparatus

beyond the human body. Just as scientists can use their eyes to approximate quantities

such as distances and speeds, music educators can use their ears to measure various

musical qualities. For example, a teacher can measure and assess a students tone by

listening and comparing the sound to memories of prior musical experiences without

using a written rubric. Yet, when codified measurement apparatuses do exist, their

repeated use can affect how people understand the qualities named within them.

Barad (2007) contrasts physicist Werner Heisenbergs position that quantities in

quantum systems such as position and momentum exist in the world waiting to be

measured with physicist Niels Bohrs assertion that quantities emerge through measurement, noting that Heisenberg eventually agreed with Bohr. According to Bohr,

concepts are idealizations or abstractions that lack determinant meanings absent

the appropriate experimental arrangements (p. 296). A particle does not exist in a

single position waiting to be measured; rather, it exists in multiple positions simultaneously. The practice of measurement forces the particle into a single, identifiable

position.

Likewise, the aspects of music-making named in a given measurement apparatus

are not waiting to be measured; they only come into existence through measurement

practices. For instance, through their measurements, those choosing to utilize the creating Model Cornerstone Assessments produce the practice of creating. In fifth

grade, creating might be notating or recording music for a specific purpose or context while using at least three of the musical elements named in the assessment instructions (National Association for Music Education, 2015b), and in eighth grade,

creating might be making music with a beginning, middle, and end for a short video

282

Journal of Research in Music Education 64(3)

(National Association for Music Education, 2015c). If the majority of music educators

in a given district or state decide to use and reuse these assessments, these practices

will come to constitute musical creating in those locations. Likewise, any repeated

assessmentbe it an adaptation of a Model Cornerstone Assessment or an assessment

formulated from scratchhas the potential to constitute a specific musical practice.

Additionally, while fifth- and eighth-grade students could take the aforementioned

tasks in a number of directions, the associated measurement apparatuses ultimately

inform how they will engage with them. Both the fifth-grade and eighth-grade assessments final scoring rubrics rate students musical creations on expressive intent and

craftsmanship (National Association for Music Education, 2015b, p. 14; 2015c,

p. 10). For the teachers and students using these measurement apparatuses to make

assessments, these qualities will contribute to understandings of creating as well as

distinguish high-quality musical creating from that of lesser quality. Such perceptions are not inevitable; they exist through the repeated boundary-making practices

necessitated by specific measurement apparatuses as well as through decisions, ranging from selecting content to determining pedagogy to connecting with music makers

outside of the classroom, that function in integration with measurement and assessment. A measurement apparatus does not just capture preexisting musical practices, it

produces musical practices.

Given the important role of measurement apparatuses, the authors of the Model

Cornerstone Assessments deserve credit for not simply preserving past boundaries.

For example, the authors of the current drafts of the Model Cornerstone Assessments

ask music technology students to construct their own message or interpretation while

arranging a cover song of their choice (National Association for Music Education,

2015e). Such tasks contrast those teachers might create in conjunction with the 1994

National Music Standards. Yet, no matter how innovative, educational measurement

apparatuses become problematic if teachers do not continually adapt them to their

individual circumstances.

While the authors of a recently added statement on the music Model Cornerstone

Assessments webpage assert that the Model Cornerstone Assessments provide adaptable assessment tasks (National Association for Music Education, 2016), the authors

of the Conceptual Framework for the National Core Arts Standards simultaneously

assert their variability and universality, writing, These tasks are intended to serve as

models to guide the development of local assessments and as such, will eventually be

benchmarked with student work and available on the NCCAS website (State

Education Agency Directors of Arts Education, 2014, p. 9). Additionally, the

Conceptual Framework authors state that the online repository for student work will

utilize the labels near standard, at standard, and above standard (State Education

Agency Directors of Arts Education, 2014, p. 6). Despite these authors acknowledgment of possible local variations, the prospect of nationwide labels for student work

may encourage educators teaching in diverse situations to adopt the same measurement apparatuses and make comparisons across school, district, and state lines.8 While

music educators might benefit from freely available choices of rigorous, adaptable

assessments and accompanying examples of student work, such action becomes

Richerme

283

problematic if music educators and students confine themselves to specific measurement apparatuses, thus placing limits on their possible musical understandings, practices, and experiences.

The Limits of Measurement Apparatuses

By bounding concepts and practices, measurement apparatuses determine inclusions

and exclusions. Barad (2007) writes, Given a particular measuring apparatus, certain

properties become determinate, while others are specifically excluded. Which properties become determinate is not governed by the desires or will of the experimenter but

rather by the specificity of the experimental apparatus (p. 19). For example, through

the Uncertainty Principle, Heisenberg demonstrated that one can measure either a particles position or momentum but not both simultaneously; the incompatibility of the

measurement apparatuses needed for each quantity limit a scientist to making one

measurement or the other.

Although different apparatuses will determine and ultimately create different quantities, none can determine all of them at once (Barad, 2007). While the proposed Model

Cornerstone Assessments name a wide range of musical qualities and practices, some

potential musical information will always cease to exist in any measurement endeavor.

For example, without alteration, the eighth-grade creating assessment task does not

allow students to express themselves through music without a clear beginning, middle,

or end or to engage with musical material in ways that a teacher may not consider

expressive. Likewise, the scoring rubrics for the creating Model Cornerstone

Assessments inevitably exclude or minimize other potentially meaningful aspects of

what someone not entrenched in these measuring apparatuses language might call

creating. Measuring creating with an apparatus highlighting virtual audiences

reactions to students cross-genre improvisations would produce markedly different

conceptions of creating than those fostered by the current drafts of the Model

Cornerstone Assessments.

More problematically, writers of materials related to the Model Cornerstone

Assessments include value-laden terminology that implies uniformity among those

interfacing with the measurement apparatuses. For instance, authors of the Conceptual

Framework for the National Core Arts Standards explain that the Model Cornerstone

Assessments are intended to engage students in applying knowledge and skills in

authentic and relevant contexts (State Education Agency Directors of Arts Education,

2014, p. 16). Such language assumes that all teachers and students will agree on what

constitutes authentic and relevant. Yet, teachers and students prior experiences,

current environments, and future aims interface with what each individual currently

terms authentic and relevant.9

Such situations create an instance of what philosopher Jean-Franois Lyotard

(1983/1988) terms the differend. He explains:

The differend is the unstable state and instant of language wherein something which must

be able to be put into phrases cannot yet be. This state includes silence, which is a negative

284

Journal of Research in Music Education 64(3)

phrase, but it also calls upon phrases which are in principle possible. This state is signaled

by what one ordinarily calls a feeling: One cannot find the words, etc. (p. 13)

These statements suggest that the differend can occur in two potentially overlapping

ways.

First, the differend forms when a practice or concept that one can put into language

does not fit within a specific discourse. For example, Deborah Bradley (2011) uses

Lyotards writings about differends to critique Wisconsins preservice music teacher

assessment guidelines, which she asserts contain Eurocentric and elitist phrase regimens that lead to the omission of certain forms of music-making from curricula. As

demonstrated through their emphasis on notation and Western musical terminology,

the revised 2014 National Core Music Standards, like their 1994 predecessors,10

clearly favor Eurocentric musical practices. Language for non-Eurocentric musical

practices exists, but music educators and students cannot argue for it within the parameters imposed by the language, albeit adaptable, of the current drafts of the Model

Cornerstone Assessments. Through its advocates voices, a musical practice or concept not named in the Model Cornerstone Assessments becomes a differend as it

asks to be put into phrases, and suffers the wrong of not being able to be put into

phrases right away (Lyotard, 1983/1988, p. 13).

A second instance of the differend occurs when an experience defies language.

While Lyotard uses the example of silence, aspects of musical experiences also seem

to fit within this explanation. For example, Susanne Langer (1957) asserts that music

does not involve the discursive symbolization inherent in language; instead, through

presentational symbols, a composer articulates subtle complexes of feeling that language cannot even name, let alone set forth (p. 222). Such aspects of music thus

constitute a differend that defies current rhetoric. In Lyotards (1983/1988) words,

What remains to be phrased exceeds what [human beings] can presently phrase

(p. 13). While it is beyond the scope of this philosophical inquiry to discuss all of the

potential facets of musical experiences that may currently lack expression in language,

aspects of the emotional, social, and ethical qualities of musical engagement may all

serve as possible instances of the differend.

While the authors of the Model Cornerstone Assessments deserve recognition

for including a wide range of music-making, no measurement apparatus will ever

address the full range of language related to the worlds vast musical practices or

account for the parts of musical experiences that defy clear quantification. As such,

the limits of the Model Cornerstone Assessments call into question the ambitious

goals articulated by the authors of the Conceptual Framework for the National Core

Arts Standards. These authors call the Model Cornerstone Assessments worthy to

teach to, adding:

Indeed, the term cornerstone is meant to suggest that just as a cornerstone anchors a

building, these assessments should anchor the curriculum around the most important

performances that students should be able to do (on their own) with acquired content

knowledge and skills. (State Education Agency Directors of Arts Education, 2014, p. 15)

Richerme

285

The image of anchors and practice of anchoring are problematic because

whether state and district leaders adopt the Model Cornerstone Assessments directly

or write their own variations, such language suggests the need to solidify music education curricula and measurement apparatuses regardless of changing local musical differends that teachers, students, and community members may find particularly

meaningful. While music educators, students, and other stakeholders will inevitably

need to make choices about what to measure at a given time and place, language such

as anchor and worthy to teach to neglects the limits of measurement apparatuses

and may dissuade individuals from highlighting the currently unmeasured and immeasurable aspects of musical experiences.

Intra-Action

Thus far in this philosophical inquiry I have primarily focused on the relationships

between measurement and student and measurement apparatus, student, and teacher.

The effect of measurement on teachers and on teacher-student relationships has gone

largely undiscussed. How might the measurement process interface with teachers

evolving selves and teacher-student engagement?

The diffractive methodology discussed earlier necessitates what Barad (2007)

terms intra-action. She distinguishes between interaction, which occurs between

discrete entities, and intra-action, through which determinant entities emerge

(p. 128). To use a physics example, interaction occurs if a wave collides with a wall

and then retreats unaffected by the event. In contrast, intra-action involves a wave and

wall that both alter as a result of their meeting; the wave changes as it is sent backward

from the wall and interferes with itself, and the wall changes as it absorbs energy from

the wave. The intra-action between wave and wall in part constitutes the evolving

identity of each. Barad asserts the intra-active nature of both scientific measurement

and existence more broadly, writing, Reality is therefore not a fixed essence. Reality

is an ongoing dynamic of intra-activity (p. 205).

The current drafts of the Model Cornerstone Assessments do provide students

opportunities to intra-act with their musical surroundings. For example, the accomplished level of the ensemble performing assessment asks students to draw on their

own interests in order to select, analyze, prepare, and perform three contrasting musical pieces with attention to appropriateness for performance contexts (National

Association for Music Education, 2015d). According to the assessment rubric, students who successfully meet this standard will have Exhibited insightful expressive

qualities representative of stylistic/composer and personal intent with attention to

nuance and sub-phrasing as a means to connect with the listener (National Association

for Music Education, 2015d, p. 13). Such writing suggests intra-actions between student and music and student and listener.

Yet, when it comes to teachers, measurements, and students, rather than intraactions, authors writing materials associated with the Model Cornerstone Assessments

imply the existence of interactions. For example, authors of the Conceptual Framework

for the National Core Arts Standards state, With a focus on processes, enduring

286

Journal of Research in Music Education 64(3)

understandings, essential questions, and assessments, these arts standards represent a

new and innovative approach to arts education that will serve students, teachers, parents, and decisionmakers now and in the future (State Education Agency Directors of

Arts Education, 2014, p. 25). The word serve implies that students, teachers, parents,

and decisionmakers have fixed identities; the materials serve preexisting needs

rather than change or produce the aforementioned actors. In other words, students,

teachers, parents, and decisionmakers interact with the named materials and with each

other, leaving each individuals identity fundamentally unchanged.

When Model Cornerstone Assessments documents do suggest that teachers might

alter as a result of intra-actions, they highlight teacher-teacher relationships rather than

teacher-student ones. For instance, authors of the Common Arts Assessment

Initiative (2014) document explain that the pilot version aims to promote collaboration and exchange of instructional ideas among teachers (p. 1). While teachers may

alter in the process of sharing ideas with each other, how they change as a result of

intra-acting with students during measurement practices remains absent from this and

similar documents.

Understanding not just measurement but existence as intra-active means that when

a teacher measures and assesses student learning, both teacher and student alter. For

instance, the teacher might change as he or she realizes that specific tone production

suggestions had little impact on the majority of students performances or as he or she

becomes curious about how a student came to make a certain compositional decision.

Simultaneously, the student may feel proud at having met a specific expectation, frustrated at not fully comprehending a measurement apparatus, or grateful for a better

understanding of what he or she can improve.

Through these intra-actions, the very idea of what it means to be a teacher and

student emerges. The one who measures comes in part to constitute a teachers

evolving self while the one who has his or her learning measured comes in part to

constitute a students evolving self. However, given that constructions of teacher

and student necessitate each other, a more accurate statement might be, Intra-active

measurement and assessment processes produce the integrated, evolving constructs of

teacher and student. Such intra-actions can bring teachers and students closer

together or distance them, cause them to work harder at their respective roles, or make

them apathetic. However, intra-actions cannot leave teachers, students, and their

relationships with each other unchanged. In short, measuring and assessing are not just

actions that teachers do to students but intra-active processes that produce teachers,

students, and music education.

Implications

In considering the nature of measurement in music education, I argued that measurement changes and ultimately in part constitutes musical experiences, measurement

apparatuses create musical practices and propagate inclusions and exclusions, and

teachers and students emerge as a result of intra-acting during measurement and

assessment processes. These assertions suggest four possible implications for practice.

Richerme

287

First, discourse about measurement, and more broadly assessment, necessitates

accompanying language noting the intra-active nature of such engagements. Words

like measure and assess are problematic because as transitive verbs, they transfer

action from one noun to another. For instance, the phrase The teacher measures student learning shifts the action away from an unchanged teacher. Such language

neglects that teachers and students alter through and are constituted by measurement

and assessment processes. Yet, given the current educational political climate, it is

impractical and potentially detrimental to eliminate words such as measure and assess

from music education discourse.

Instead, music educators might complement terms such as measure and assess

with language such as grow, develop, and become. For example, teachers, students,

and policymakers might make statements such as, Students develop through selfassessments of their improvisations or Students grow when teachers measure and

assess their compositions. Rather than implying that measurement takes a snapshot of

existing practices, such language acknowledges that measurement, in conjunction

with assessment, alters and inevitably produces musical experiences. The aforementioned statements also have the added advantage of positioning measurement and

assessment as processes that students participate in rather than as acts done to them.

Placing students as the subject of statements about measurement and assessment reinforces their active role in these processes.

Teachers, students, and policymakers could also use complementary language to

acknowledge the intra-active nature of teachers measurement and assessment experiences. For instance, authors might consider phrases such as, By measuring and assessing students, teachers can become more responsive to their developmental needs. Such

discourse emphasizes that rather than distanced observers, teachers evolve through and

are constituted by their measurement and assessment practices.

A second implication for policy and practice is that because measurement apparatuses produce and reinforce a particular set of musical experiences, policymakers,

teachers, and students might empower themselves and each other to engage critically

with and potentially alter them. Regardless of whether teachers and students use measurement apparatuses they created or ones formulated by others, they might consider

the limits of their existing practices. For example, teachers and students might examine

the instructions, self-assessments, and teacher rubrics associated with the Model

Cornerstone Assessments proposed for their grade level or musical elective and discuss

what aspects of music that they find meaningful are missing from such documents.

Because assessment involves the combination of measurement and evaluation

(Payne, 2003), music educators and students might also interrogate how they make

value judgments about measured quantities. For instance, they could ask: What meaning do we find in these value judgments, and how do they affect our musical and

educative experiences? To what extent do these evaluations reflect the values of music

makers in our multiple communities? How might we evaluate these measured quantities differently?

Additionally, Barad (2007) asserts the need for analyzing how boundaries are produced rather than presuming sets of well-worn binaries in advance (p. 30). Drawing

288

Journal of Research in Music Education 64(3)

on this statement, teachers and students might engage in critical dialogue about who

produced their measurement apparatuses, how they created them, and for what purposes. As a result of such explorations, teachers and students might consider how they

could alter their existing measurement apparatuses as well as create possible alternative measurement apparatuses. Such action aligns with a conception of the Model

Cornerstone Assessments as adaptable models rather than unchangeable mandates.

By giving themselves the agency to engage critically with and alter measurement

apparatuses, music educators and students can develop higher order thinking skills

related to the process of measurement and adopt measurement apparatuses meaningful

for their particular circumstances.

Third, teachers, students, and policymakers might balance discourse calling for

relevant and reliable assessments (e.g., State Education Agency Directors of Arts

Education, 2014, p. 16) with language promoting spaces for uncertainty, experimentation, and vulnerability. As such, music education policymakers might reconsider or

qualify language such as The evidence that is collected tells students what is most

important for them to learn. What is not assessed is likely to be regarded as unimportant (State Education Agency Directors of Arts Education, 2014, p. 15). Perhaps drawing on Lyotards concept of the differend, music educators, students, and policymakers

might recognize and celebrate that there exist aspects of musical experiences that defy

the language of measurement and assessment. While teachers can perhaps hint at

unnamable musical facets using language such as poetry and metaphors,11 they might

also facilitate musical spaces not directly focused on measurable goals. Although past

measurements and assessments will always influence subsequent musical endeavors,

by complementing such discourse with the promotion of unmeasured experiences,

music education teachers, students, and policymakers can meet the demands of the

existing education climate while retaining possibilities for experiences highlighting

the unique aspects of musical engagements praised by philosophers such as Langer.

Finally, if measurement and assessment are intra-active processes through which

student and teacher emerge, then music educators and students might question to

what extent they feel satisfied with the evolving identities forming as a result of current measurement and assessment intra-actions and contemplate the possibilities of

changes to those intra-actions. Music educators might ask: How can I promote measurement and assessment intra-actions through which students emerge possessing

the dispositions needed to seek out more musical growth and to feel capable and

empowered to continue learning music beyond school walls? To what extent do my

measurement and assessment intra-actions benefit or harm my relationships with students as well as my own conception of myself as teacher? What possible students

and teachers do my current measurement and assessment practices exclude or inhibit

from emerging, and how might I act otherwise?

Moreover, since Barad (2007) conceives of intra-action not just as a part of measurement but of life, music educators and students might reimagine music education as a

fundamentally intra-active process. As such, teachers and students might consider how

the assumptions, aims, and questions underlying all aspects of their musically educative

intra-actions contribute to their evolving conceptions of students, teachers, and

Richerme

289

relationships between the two. For example, music educators and students could question how their intra-actions with music makers outside of the classroom enable the

emergence not just of students but of musicians who consider themselves contributing members of various local and global musical communities. Teachers and students might also contemplate how their musical intra-actions reinforce exclusions,

social injustices, and hegemonic systems in their school and beyond, perhaps countering such practices with intra-actions favoring empathy, openness, and reflective ethical action. Such undertakings involve asking not just how musical endeavors can alter

others but how teachers, students, music-making, and their interrelationships change

in the process.

In summary, current discourse surrounding the music Model Cornerstone

Assessments assumes a reflective and interactive worldview in which measurement

apparatuses capture existing circumstances. Yet, Barad (2007) demonstrates the

inaccuracy of such assumptions with regard to measurement, instead positing the concepts of diffraction and intra-action and explaining measurement apparatuses as

boundary-making practices. Measurement apparatuses produce both musical experiences and evolving entities such as students and teachers. By reconsidering their

language and action, policymakers, music educators, and students can promote more

accurate understandings of measurement and assessment processes and empower

themselves to reimagine their intra-actions with measurement and with each other.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank Phil Richerme, professor of physics at Indiana University, for

verifying the scientific accuracy of this paper and offering suggestions for further clarification.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship,

and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this

article.

Notes

1. The authors of the music Model Cornerstone Assessments are not the same as those who

wrote the Conceptual Framework, but the webpage on which the Conceptual Framework

is located (http://www.nationalartsstandards.org/) includes a prominent link to the music

Model Cornerstone Assessments webpage. As such, while some authors of the Model

Cornerstone Assessments may have different goals than the authors of the Conceptual

Framework, it is important to consider how their work is situated within broader discourse

related to the Model Cornerstone Assessments.

2. In offering this investigation, I do not aim to dismiss or undermine the work of those generously volunteering their time to author the documents discussed here. Given the contemporary education paradigm, the current drafts of Model Cornerstone Assessments serve the

290

Journal of Research in Music Education 64(3)

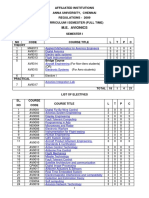

Image 1. Diffractive pattern.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

important function of providing music educators a practical starting point for thoughtful,

multifaceted assessments that go beyond simple performance tasks or knowledge recall.

A complete list of the current drafts is available at http://www.nafme.org/my-classroom/

standards/mcas-information-on-taking-part-in-the-field-testing/.

Barad (2007) initially explains that in physics, diffraction occurs when the phenomena

being measured self-interacts. For example, a diffractive pattern emerges when a wave

interacts with itself when passing through an opening. Image 1 demonstrates the constructive and destructive interference that constitute such phenomena. In this diffractive pattern,

the constructive interference is most visible in the center of the image, while the destructive interference is most visible at the top and bottom next to the wall. When constructing a diffractive methodology, Barad expands this explanation to include intra-actions

between different entities.

The Model Cornerstone Assessments are meant to be adaptable. While this scenario uses a

draft of a Model Cornerstone Assessment as written, it illuminates the nature of the practices of

measurement and assessment in education more broadly and thus has implications for teachers

adapting the Model Cornerstone Assessments as well as those using other assessments.

While no exact parallel exists in physicsa researcher would not share the results of

measurement with the particle under investigationBarad (2007) extends the process of

diffraction to interpersonal relationships, using it as justification for her concept of intraaction, which is explained in a later section of this article. Thus, it is consistent with Barads

philosophy to apply her writings about diffraction not just to the process of measurement

but to explanations of interpersonal assessment practices that utilize past measurements.

Since all of the current Model Cornerstone Assessment drafts indicate that they are designed

to measure student achievement (e.g., National Association for Music Education, 2015a,

p. 2; National Association for Music Education, 2015c, p. 2), referring to them as measurement apparatuses is consistent with their authors language.

While most authors of the Conceptual Framework for the National Core Arts Standards

are not directly affiliated with the music Model Cornerstone Assessments, Scott Shuler

and Richard Wells are both co-chairs of the National Core Music Standards writing team

Richerme

291

and music MCA Benchmarking Facilitators (see http://nccas.wikispaces.com/Model

+Cornerstone+Assessment+Benchmarking+Landing+Page). The authors of the music

Model Cornerstone Assessments webpage (http://www.nafme.org/my-classroom/stan

dards/mcas-information-on-taking-part-in-the-field-testing/) do not directly note the

possibility of benchmarking student work. However, on the National Coalition for Core

Arts Standards website, there is a statement thanking those participating in the current

music Model Cornerstone Assessment pilot testing displayed alongside hyperlinks to

both the Conceptual Framework and a webpage entitled MCA Benchmarking 2015

(see http://nccas.wikispaces.com/High+School+MCA+Piloting+Teachers). Although

the authors of music Model Cornerstone Assessments may not have the same goals as

these other stakeholders, it is important to examine the discourse surrounding their work.

9. A recently added statement on the music Model Cornerstone Assessments webpage

explains them as part of a move to authentic and contextually based assessments

(National Association for Music Education, 2016). The authors of this statement suggest a

possible move away from the universal conceptions of authenticity and relevance implied

by the authors of the Conceptual Framework.

10. See, for example, Benedict (2007) and Schmidt (1996).

11. See, for example, Kristevas (1974/1984) assertions about the possibilities of poetic

language.

References

Allsup, R. E. (2015). Music teacher quality and the problem of routine expertise. Philosophy of

Music Education Review, 23, 524. doi:10.2979/philmusieducrevi.23.1.5

American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, Pub. L No. 111-5, 123, Stat. 115 (2009).

Arostegui, J. L. (2003). On the nature of knowledge: What we want and what we get with

measurement in music education. International Journal of Music Education, 40, 100115.

doi:10.1177/025576140304000108

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Benedict, C. L. (2007). Naming our reality: Negotiating and creating meaning in the margin.

Philosophy of Music Education Review, 15, 2336.

Bowman, W. (1998). Philosophical perspectives on music. New York, NY: Oxford University

Press.

Bradley, D. (2011). In the space between the rock and the hard place: State teacher certification

guidelines and music education for social justice. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 45(4),

7996. doi: 0.5406/jaesteduc.45.4.0079

Common Arts Assessment Initiative. (2014). Retrieved from http://www.nafme.org/my-classroom/

standards/mcas-information-on-taking-part-in-the-field-testing/Common Core State Standards.

Darling-Hammond, L., Amrein-Beardsley, A., Haertel, E., & Rothstein, J. (2012). Evaluating

teacher evaluation. Phi Delta Kappan, 93(6), 815. doi:10.1177/003172171209300603

Deuze, M. (2012). Media life. Cambridge, UK: Policy Press.

Fenwick, T., & Edwards, R. (2010). Actor-network theory in education. New York, NY:

Routledge.

Froehlich, H., & Frierson-Campbell, C. (2012). Inquiry in music education. New York, NY:

Taylor & Francis.

Horsley, S. (2014). Globally convergent accountability policies and the cultural status of

state funded school music programs: A state-level comparison. In P. Gouzouasis (Ed.),

292

Journal of Research in Music Education 64(3)

Proceedings of the 17th biennial international seminar of the commission on music policy:

Culture, education, and media (pp. 7278). Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia.

Jorgensen, E. R. (1992). On philosophical method. In R. Colwell (Ed.), Handbook of research

on music teaching and learning (pp. 91114). New York, NY: Schirmer Books.

Kristeva, J. (1984). Revolution in poetic language (M.Waller, Trans.). New York, NY: Columbia

University Press. (Original work published 1974)

Langer, S. K. (1957). Philosophy in a new key: A study in the symbolism of reason, rite, and art

(3rd ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lyotard, J. (1988). The differend: Phrases in dispute (G. Van Den Abbeele, Trans.). Minneapolis,

MN: University of Minnesota Press. (Original work published 1983)

Mehta, J. (2013). The allure of order: High hopes, dashed expectations, and the troubled quest

to remake American schooling. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Miller, D., Linn, R. I., & Gronlund, N. E. (2009). Measurement and assessment in teaching

(10th ed.). Upper River Saddle, NJ: Pearson.

National Association for Music Education. (2015a). Music model cornerstone assessment:

Artistic process: Creating 2nd grade general music. Retrieved from http://www.nafme.

org/wp-content/files/2014/11/Music_MCA_Grade_2_GenMus_Creating_2015.pdf

National Association for Music Education. (2015b). Music model cornerstone assessment:

Artistic process: Creating 5th grade general music. Retrieved from http://www.nafme.org/

wp-content/files/2014/11/Music_MCA_Grade_5_GenMus_Creating_2015.pdf

National Association for Music Education. (2015c). Music model cornerstone assessment:

Artistic process: Creating 8th grade general music. Retrieved from http://www.nafme.org/

wp-content/files/2014/11/Music_MCA_Grade_8_GenMus_Creating_2015.pdf

National Association for Music Education. (2015d). Music model cornerstone assessment:

Artistic process: Performing ensembles: Accomplished & advanced. Retrieved from

http://www.nafme.org/wp-content/files/2014/11/Music_MCA_Ensemble_Performing_

Accomplished_Advanced_2015.pdf

National Association for Music Education. (2015e). Music model cornerstone assessment:

Technology: Proficient. Retrieved from http://www.nafme.org/wp-content/files/2014/11/

Music_MCA_Technology_Proficient_2015.pdf

National Association for Music Education. (2016). Student assessment using Model Cornerstone

Assessments. Retrieved from http://www.nafme.org/my-classroom/standards/mcas-infor

mation-on-taking-part-in-the-field-testing/

No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, Pub. L. No. 107-110, 115, Stat. 1425 (2002).

OConner, J. (2014, April 21). Why Florida parents want to opt their kids out of state tests.

Retrieved from http://stateimpact.npr.org/florida/2014/04/21/why-florida-parents-want-toopt-their-kids-out-of-state-tests/

Orlikowski, W. J. (2015). The sociomateriality of organisational life: Considering technology

in management research. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 39, 125141. doi:10.1093/cje/

bep058

Payne, D. A. (2003). Applied educational assessment (2nd ed.). Toronto: Wadsworth.

Perrine, W. M. (2013). Music teacher assessment and Race to the Top: An initiative in Florida.

Music Educators Journal, 100(1), 3944. doi:10.1177/0027432113490738

Phelps, R. P., Ferrara, L., & Goolsby, T. W. (1993). A guide to research in music education

(4th ed.). Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press.

Reynolds, C. R., Livingston, R. B., & Willson, V. (2009). Measurement and assessment in

education (2nd ed.). Upper River Saddle, NJ: Pearson.

Richerme

293

Sanchez, C. (2015, March 5). Why some parents are sitting kids out of tests. National Public

Radio. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2015/03/05/390239788/why-someparents-are-sitting-kids-out-of-tests

Schmidt, C. M. (1996). Who benefits? Music education and the National Standards. Philosophy

of Music Education Review, 4, 7182.

Scott, S. J. (2012). Rethinking the roles of assessment in music education. Music Educators

Journal, 98(3), 3135. doi:10.1177/0027432111434742

Shuler, S. C. (2012). Music assessment, part 2Instructional improvement and teacher evaluation. Music Educators Journal, 98(3), 710. doi:10.1177/0027432112439000

State Education Agency Directors of Arts Education. (2014). National Core Arts Standards:

A conceptual framework for arts learning. Retrieved from http://www.nationalartsstandards

.org/content/conceptual-framework

Taguchi, H. L. (2010). Going beyond the theory/practice divide in early childhood education:

Introducing an intra-active pedagogy. New York, NY: Routledge.

Thorndike, R. M., & Thorndike-Christ, T. (2010). Measurement and evaluation in psychology

and education (8th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

U.S. Department of Education. (2012). ESEA flexibility policy document. Retrieved from http://

www2.ed.gov/policy/elsec/guid/esea-flexibility/index.html

Wegerif, R. (2013). Dialogic: Education for the Internet age. New York, NY: Routledge.

Wesolowski, B. C. (2012). Understanding and developing rubrics for music performance

assessment. Music Educators Journal, 98(3), 3642. doi:10.1177/0027432111432524

Author Biography

Lauren Kapalka Richerme is an assistant professor of music education at the Indiana

University Jacobs School of Music. Her research interests include philosophy and education

policy.

Submitted July 15, 2015; accepted April 26, 2016.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Collins Reading For IELTS PDFDocument145 pagesCollins Reading For IELTS PDFMaria Leah dela Rosa Tapawan100% (1)

- Rieber Sealing in AmericaDocument10 pagesRieber Sealing in Americaulloap*100% (1)

- Book UploadDocument270 pagesBook Uploadchuan88100% (20)

- Book UploadDocument270 pagesBook Uploadchuan88100% (20)

- Tugas Metalurgi LasDocument16 pagesTugas Metalurgi LasMizan100% (2)

- Monday Thursday: GMUB Jazz Project Schedule 2018-2019Document1 pageMonday Thursday: GMUB Jazz Project Schedule 2018-2019TsogtsaikhanEnerelNo ratings yet

- Financial Report 2018 2019Document14 pagesFinancial Report 2018 2019TsogtsaikhanEnerelNo ratings yet

- Some Mistakes When Teaching PianoDocument10 pagesSome Mistakes When Teaching PianoTsogtsaikhanEnerelNo ratings yet

- Susan Hallam Music Development - Research PDFDocument32 pagesSusan Hallam Music Development - Research PDFKaren MoreiraNo ratings yet

- IELTS - Write Right - Retyped by Hội các sĩ tử luyện thi IELTSDocument260 pagesIELTS - Write Right - Retyped by Hội các sĩ tử luyện thi IELTSNguyen Duc Tuan100% (16)

- Issue of Music EducationDocument2 pagesIssue of Music EducationTsogtsaikhanEnerelNo ratings yet

- Golliwog's CakewalkDocument2 pagesGolliwog's CakewalkTsogtsaikhanEnerelNo ratings yet

- The Piano Lesson Companion Book: Level 1Document17 pagesThe Piano Lesson Companion Book: Level 1TsogtsaikhanEnerelNo ratings yet

- Issue of Music Education 1Document16 pagesIssue of Music Education 1TsogtsaikhanEnerelNo ratings yet

- Music Education IssueDocument20 pagesMusic Education IssueTsogtsaikhanEnerelNo ratings yet

- IELTS - Write Right - Retyped by Hội các sĩ tử luyện thi IELTSDocument260 pagesIELTS - Write Right - Retyped by Hội các sĩ tử luyện thi IELTSNguyen Duc Tuan100% (16)

- Golliwog's CakewalkDocument2 pagesGolliwog's CakewalkTsogtsaikhanEnerelNo ratings yet

- Thermal Oil Boiler Vega PDFDocument2 pagesThermal Oil Boiler Vega PDFrafiradityaNo ratings yet

- Analysis and Design of Column: Chapter ThreeDocument23 pagesAnalysis and Design of Column: Chapter Threejebril yusufNo ratings yet

- 2068 TI 908miller CodanDocument24 pages2068 TI 908miller CodanFlo MarineNo ratings yet

- Tolerances and FitsDocument12 pagesTolerances and FitsnikitaNo ratings yet

- Fields of Application: About The TestsDocument47 pagesFields of Application: About The TestsStefan IonelNo ratings yet

- Cfa EqrsDocument2 pagesCfa EqrsarunachelamNo ratings yet

- Sound Isolation 2017Document81 pagesSound Isolation 2017vartika guptaNo ratings yet

- Speech About Go GreenDocument4 pagesSpeech About Go GreenMuhammadArifAzw100% (1)

- Identification of Textile Fiber by Raman MicrospecDocument9 pagesIdentification of Textile Fiber by Raman MicrospecTesfayWaseeNo ratings yet

- Hot and Dry Climate SolarPassiveHostelDocument4 pagesHot and Dry Climate SolarPassiveHostelMohammed BakhlahNo ratings yet

- Delta Industrial Articulated Robot SeriesDocument15 pagesDelta Industrial Articulated Robot Seriesrobotech automationNo ratings yet

- Electric Motor Problems & Diagnostic TechniquesDocument12 pagesElectric Motor Problems & Diagnostic Techniquesjuanca249No ratings yet

- Tos 2ND and 3RD Periodical Test Science 8 Tom DS 1Document5 pagesTos 2ND and 3RD Periodical Test Science 8 Tom DS 1Aileen TorioNo ratings yet

- Chapter1 Electrostatic 2016 ReviewedDocument98 pagesChapter1 Electrostatic 2016 ReviewedSyaza IzzatyNo ratings yet

- 8620 Wearable Ring Scanner Data Sheet en PDFDocument2 pages8620 Wearable Ring Scanner Data Sheet en PDFDinesh Kumar DhundeNo ratings yet

- F5 KSSM Tutorial 1.1 (Force and Motion Ii)Document13 pagesF5 KSSM Tutorial 1.1 (Force and Motion Ii)Alia Qistina Mara KasmedeeNo ratings yet

- Mass and Thermal Balance During Composting of A Poultry Manure-Wood Shavings Mixture at Different Aeration RatesDocument9 pagesMass and Thermal Balance During Composting of A Poultry Manure-Wood Shavings Mixture at Different Aeration RatesPrashant RamNo ratings yet

- Case Studies in Engineering Failure Analysis: K. Gurumoorthy, Bradley D. Faye, Arindam GhoshDocument8 pagesCase Studies in Engineering Failure Analysis: K. Gurumoorthy, Bradley D. Faye, Arindam GhoshRif SenyoNo ratings yet

- Lab Equipment PowerpointDocument41 pagesLab Equipment PowerpointPatrick Jordan S. EllsworthNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 4 - Design of Footings-2-Isolated FootingDocument10 pagesChapter - 4 - Design of Footings-2-Isolated FootingAdisalem BelayNo ratings yet

- Soil CompactionDocument24 pagesSoil Compactionsyah123No ratings yet

- Activity 1Document6 pagesActivity 1Aldwin AjocNo ratings yet

- HW 3Document3 pagesHW 3Siva RamNo ratings yet

- CPRF Analysis PDFDocument8 pagesCPRF Analysis PDFMohd FirojNo ratings yet

- Avionics Unit 1Document25 pagesAvionics Unit 1Raahini IzanaNo ratings yet

- Filmgate Technical Screen Print InformationDocument34 pagesFilmgate Technical Screen Print InformationramakrishnafacebookNo ratings yet

- Light NcertDocument55 pagesLight NcertDani MathewNo ratings yet

- Unit Plan M7 S.Y. 2020 2021Document14 pagesUnit Plan M7 S.Y. 2020 2021dan teNo ratings yet