Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Female World of Cards and Holidays Women, Families, and The Work of Kinship

Uploaded by

André Justino OmisileOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Female World of Cards and Holidays Women, Families, and The Work of Kinship

Uploaded by

André Justino OmisileCopyright:

Available Formats

The Female World of Cards and Holidays: Women, Families, and the Work of Kinship

Author(s): Micaela di Leonardo

Source: Signs, Vol. 12, No. 3 (Spring, 1987), pp. 440-453

Published by: University of Chicago Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3174331

Accessed: 22-02-2016 18:28 UTC

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

http://www.jstor.org/stable/3174331?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/

info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content

in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship.

For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Signs.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 164.41.232.88 on Mon, 22 Feb 2016 18:28:23 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE FEMALE WORLD OF CARDS

AND HOLIDAYS: WOMEN, FAMILIES,

AND THE WORK OF KINSHIP'

MICAELA DI LEONARDO

Whyis itthatthemarriedwomenofAmericaare supposedtowrite

all thelettersand sendall thecardsto theirhusbands'families?My

old man is a muchbetterwriterthanI am, yethe expectsme to

correspondwithhiswholefamily.IfI askedhimtocorrespondwith

mine,he would blow a gasket.[LETTER TO ANN LANDERS]

careWomen'splace in man'slifecyclehas been thatofnurturer,

taker,and helpmate,theweaverofthosenetworksofrelationships

on which she in turnrelies. [CAROL GILLIGAN, In a Different

Voice ]2

Feministscholarsin the past fifteenyears have made great stridesin

ofthe relationsamonggender,kinship,

new understandings

formulating

JohnWilloughby,

Manythanksto CynthiaCostello,RaynaRapp, RobertaSpalter-Roth,

and BarbaraGelpi, Susan Johnson,and SylviaYanagisakoof Signsfortheirhelp withthis

article.I wishin particularto acknowledgetheinfluenceofRaynaRapp'sworkon myideas.

1Acknowledgment

formyparaphraseof her

and gratitudeto CarrollSmith-Rosenberg

title,"The Female World of Love and Ritual:RelationsbetweenWomen in NineteenthCenturyAmerica,"Signs:JournalofWomenin Cultureand Society1, no. 1 (Autumn1975):

1-29.

2 Ann Landers letterprintedin WashingtonPost (April15, 1983); Carol Gilligan,In a

DifferentVoice (Cambridge,Mass.: HarvardUniversityPress, 1982), 17.

[Signs:Journalof Womenin Cultureand Society1987, vol. 12, no. 3]

C 1987 by The Universityof Chicago. All rightsreserved.0097-9740/87/1203-0003$01.00

440

This content downloaded from 164.41.232.88 on Mon, 22 Feb 2016 18:28:23 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Spring1987 / SIGNS

and thelargereconomy.As a resultofthispioneeringresearch,womenare

newlyvisibleand audible,no longersubmergedwithintheirfamilies.We

see householdsas loci ofpoliticalstruggle,inseparablepartsofthe larger

societyand economy,ratherthanas havensfromthe heartlessworldof

Andhistoricaland culturalvariationsin kinshipand

industrialcapitalism.3

have

clearerwiththematuration

offeminist

become

forms

historical

family

and social-scientific

scholarship.

Two theoreticaltrends have been key to this reinterpretation

of

women'sworkand familydomain.The firstis theelevationto visibility

of

women's nonmarketactivities-housework,child care, the servicingof

ofall theseactivitiesas

men,and thecareoftheelderly-and thedefinition

labor, to be enumeratedalongsideand countedas partof overallsocial

reproduction.The second theoreticaltrendis the nonpejorativefocuson

women's domesticor kin-centerednetworks.We now see themas the

of kinship

productsof conscious strategy,as crucialto the functioning

women's

as

sources

autonomous

and

of

systems,

power

possibleprimary

sites of emotionalfulfillment,

and, at times, as the vehicles foractual

survivaland/orpoliticalresistance.4

Recently,however,a divisionhas developed betweenfeministinterpretersof the "labor"and the "network"perspectiveson women'slives.

Those who focuson women'sworktend to envisionwomenas sentient,

goal-orientedactors,while thosewho concernthemselveswithwomen's

ties to otherstend to perceivewomenprimarily

in termsofnurturance,

The mostcelebratedrecentexampleofthis

other-orientation-altruism.

3 Heidi I. Hartmann,"The Familyas the Locus ofGender,Class, and PoliticalStruggle:

The ExampleofHousework,"Signs6, no. 3 (Spring1981):366-94; and ChristopherLasch,

Haven in a HeartlessWorld: The FamilyBesieged(New York:Basic Books, 1977).

4 Representativeexamples of the firsttrend include JoannVanek, "Time Spent on

American231 (November1974): 116-20; RuthSchwartzCowan, "A

Housework,"Scientific

Case Studyof Technologicaland Social Change: The WashingMachine and the Working

Wife,"in Clio's ConsciousnessRaised, ed. Mary Hartmannand Lois Banner (New York:

Harper& Row, 1974),245-53; AnnOakley,Women'sWork:TheHousewife,Pastand Present

(New York: Vintage, 1974); Hartmann;and Susan Strasser,Never Done: A Historyof

AmericanHousework(New York:PantheonBooks, 1982). Key contributions

to the second

trendinclude Louise Lamphere,"Strategies,Cooperationand ConflictamongWomen in

Domestic Groups," in Women,Culture and Society,ed. Michelle ZimbalistRosaldo and

Louise Lamphere (Stanford,Calif.: StanfordUniversityPress, 1974), 97-112; Mina Davis

Caulfield,"Imperialism,the Familyand theCulturesofResistance,"SocialistRevolution20

(October 1974): 67-85; Smith-Rosenberg;

SylviaJunkoYanagisako,"Women-centeredKin

Networksand UrbanBilateralKinship,"AmericanEthnologist4, no. 2 (1977): 207-26; Jane

Humphries,"The WorkingClass Family,Women'sLiberationand Class Struggle:The Case

ofNineteenthCenturyBritishHistory,"ReviewofRadical PoliticalEconomics9 (Fall 1977):

25-41; Blanche Weisen Cook, "Female SupportNetworksand PoliticalActivism:Lillian

Wald, CrystalEastman,Emma Goldman,"inA HeritageofHer Own,ed. NancyF. Cottand

Elizabeth H. Pleck (New York: Simon & Schuster,1979); Temma Kaplan, "Female Consciousnessand CollectiveAction:The Case ofBarcelona,1910-1918,"Signs7, no. 3 (Spring

1982): 545-66.

441

This content downloaded from 164.41.232.88 on Mon, 22 Feb 2016 18:28:23 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

di Leonardo

/ THE WORK OF KINSHIP

ofhistoriansAlice Kessler-Harrisand

divisionis the opposingtestimony

RosalindRosenbergin theEqual Employment

Commission's

Opportunity

case againstSears Roebuck and Company. Kesslersex discrimination

Harris argued that Americanwomen historicallyhave activelysought

higher-paying

jobs and havebeen preventedfromgainingthembecause of

sexdiscrimination

byemployers.RosenbergarguedthatAmericanwomen

in the nineteenthcenturycreated among themselves,throughtheir

domesticnetworks,a "women'sculture"thatemphasizedthe nurturance

ofchildrenand othersand themaintenanceoffamilylifeand thatdiscouraged women fromcompetitionover or heavy emotionalinvestmentin

demanding,high-paidemployment.5

I shallnothere addressthisspecificdebatebut,instead,shallconsider

its theoreticalbackgroundand implications.I shallarguethatwe need to

fuse,ratherthanto oppose, thedomesticnetworkand laborperspectives.

In whatfollows,I introducea newconcept,theworkofkinship,bothtoaid

empiricalfeministresearchon women, work,and familyand to help

advancefeminist

theoryin thisarena.I believethattheboundary-crossing

dichotnatureofthe concepthelps to confoundthe self-interest/altruism

omy,forcingus froman either-orstanceto a positionthatincludesboth

perspectives.I hope in thisway to contributeto a morecriticalfeminist

visionofwomen'slives and the meaningoffamilyin the industrialWest.

in Northern

In my recent field researchamong Italian-Americans

California,I foundmyselfconsideringthe relationsbetween women's

I was concernedwith

kinshipand economiclives. As an anthropologist,

Americannuclearfamilyor housepeople's kinlivesbeyondconventional

hold boundaries.To thisend, I collectedindividualand familylifehistories, askingabout all kinand close friendsand theiractivities.I was also

veryinterestedinwomen'slabor.As I satwithwomenandlistenedtotheir

accountsoftheirpast and presentlives,I began to realizethattheywere

involvedin threetypesofwork:houseworkand childcare, workin the

labor market,and the workofkinship.6

and ritualcelebraBykinworkI referto theconception,maintenance,

kinties, includingvisits,letters,telephonecalls,

tionofcross-household

presents,and cards to kin; the organizationof holidaygatherings;the

creationand maintenanceofquasi-kinrelations;decisionsto neglector to

5 On this debate, see Jon Weiner, "Women's Historyon Trial," Nation 241, no. 6

(September7, 1985): 161, 176, 178-80; KarenJ. Winkler,"Two Scholars'Conflictin Sears

Sex-BiasCase Sets OffWar in Women'sHistory,"ChronicleofHigherEducation(February

5, 1986), 1, 8; RosalindRosenberg,"What Harms Women in the Workplace,"New York

Times(February27, 1986);AliceKessler-Harris,

Commis"Equal Employment

Opportunity

sionvs. Sears Roebuckand Company:A PersonalAccount,"RadicalHistoryReview35 (April

1986): 57-79.

6 Portionsofthe

following

analysisare reportedin Micaela di Leonardo,The Varietiesof

EthnicExperience:Kinship,Class and GenderamongCaliforniaItalian-Americans

(Ithaca,

N.Y.: Cornell UniversityPress, 1984), chap. 6.

442

This content downloaded from 164.41.232.88 on Mon, 22 Feb 2016 18:28:23 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Spring1987 / SIGNS

intensifyparticularties; the mentalwork of reflectionabout all these

ofalteringimagesoffamily

activities;and thecreationand communication

and kinvis-a-vistheimagesofothers,bothfolkand massmedia. Kinwork

is a keyelementthathas been missingin the synthesisofthe "household

labor" and "domesticnetwork"perspectives.In our emphasison individual women's responsibilitieswithinhouseholdsand on the job, we

reflectthecommonpictureofhouseholdsas nuclearunits,tiedperhapsto

thelargersocialand economicsystem,but notto each other.We missthe

point of telephone and softdrinkadvertising,of women's magazines'

confusednostalgiaforthemythical

Amerholidayissues,ofcommentators'

ican extendedfamily:it is kinshipcontactacross households,as muchas

our culturalexpectationof satiswomen'sworkwithinthem,thatfulfills

life.

fyingfamily

takestime,intention,

Maintainingthesecontacts,thissense offamily,

and skill. We tend to thinkof human social and kin networksas the

thesocialtracescreatedby

epiphenomenaofproductionand reproduction:

we see themas partof

our materiallives. Or, in theneoclassicaltradition,

leisure activities,outside an economic purviewexcept insofaras they

involveconsumptionbehavior.But the creationand maintenanceofkin

and quasi-kinnetworksin advanced industrialsocieties is work; and,

moreover,it is largelywomen'swork.

The kin-worklens broughtintofocusnew perspectiveson myinformants'familylives. First,lifehistoriesrevealedthatoftenthe veryexistence ofkincontactand holidaycelebrationdepended on the presenceof

an adult woman in the household. When couples divorcedor mothers

died, the workof kinshipwas leftundone; when women entered into

sanctionedsexual or maritalrelationshipswithmen in these situations,

the men's kinshipnetworksand organizedgatherings

theyreconstituted

and holidaycelebrations.Middle-agedbusinessmanAl Bertini,forexample, recalledthedeathofhismotherinhisearlyadolescence:"I thinkthat's

probablyone ofthebiggestlossesinlosinga family-yeah,I rememberas a

childwhenmyMom was alive . .. theholidaysweretreatedwithenthusiasm and love . . . aftershe died the attemptwas therebut itjust didn't

materialize."Laterin life,whenAl Bertiniand hiswifeseparated,hisown

and his sonJim'sparticipation

in extended-family

contactdecreasedrapida

But

when

ly.

Jimbegan relationshipwithJaneBateman,she and he

moved in with Al, and Jimand Jane began to invitehis kin over for

holidays.Janesingle-handedly

plannedand cooked the holidayfeasts.

Kinwork,then,is likehouseworkand childcare:menin theaggregate

do notdo it. It differs

fromtheseformsoflaborinthatitis harderformento

substitutehired labor to accomplishthese tasksin the absence of kinswomen. Second, I foundthatwomen,as theworkersin thisarena,generally had much greaterkin knowledgethan did their husbands, often

includingmoreaccurateand extensiveknowledgeoftheirhusbands'fami443

This content downloaded from 164.41.232.88 on Mon, 22 Feb 2016 18:28:23 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

di Leonardo / THE WORK OF KINSHIP

lies. This was truebothofmiddle-agedand youngercouplesand surfaced

in theformofhumorousarguments

and

as a phenomenonin myinterviews

in wives' detailed additionsto husbands'narratives.Nick Meraviglia,a

middle-agedprofessional,discussedhis Italianantecedentsin the presence ofhis wife,Pina:

was a veryoutspokenman, and it was reNick: My grandfather

portedhe tookoffforthehillswhenhe foundoutthatMussolini was in power.

Pina: Andhe was a verytallman;he used tohavetobowhishead to

get inside doors.

Nick: No, thatwas myuncle.

Pina: Your grandfather

too, I've heardyourmothersay.

Nick: My motherhas a sisterand a brother.

Pina: Two sisters!

Nick: You're right!

Pina: Maria and Angelina.

feudsand crises

Womenwere also muchmorewillingto discussfamily

and theirown roles in them;men tendedto repeatformulaicstatements

assertingfamilyunityand respectability.(This was much less true for

youngermen.) Joe and Cetta Longhinotti'sstatementsillustratethese

tendencies.Joerespondedto myquestionaboutkinrelations:"We all get

along. As a rule, relatives,you got nothingbut trouble."Cetta, instead,

discussedher relationswitheach ofher grownchildren,theirwives,her

in-laws,and her own blood kin in detail. She did not hide the factthat

relationswere strainedin several cases; she was eager to discuss the

evolutionofproblemsand to seek myopinionsofher actions.Similarly,

withone ofherbrothers

Pina Meravigliatoldthefollowing

storyofherfight

with hystericallaughter:"There was some bitingand hair pullingand

choking... itwas terrible!I shouldn'teventellyou .... "Nick,meanwhile,

an imageoffamilyunityand respectawas concernedabout maintaining

bility.

Also, men waxed fluentwhile womenwere quite inarticulatein discussingtheirpast and presentoccupations.When askedabouttheirwork

and NickMeraviglia,unionbakerand professional,

lives,JoeLonghinotti

oftheirworkcareers.CettaLonghigave detailednarratives

respectively,

nottiand Pina Meraviglia,clericaland formerclerical,respectively,offeredonlyshortdescriptionsfocusingon factorsofambience,suchas the

"lovelythings"sold by Cetta's firm.

These patternsare notrepeatedin theyoungergeneration,especially

among youngerwomen, such as Jane Bateman,who have managedto

acquire trainingand jobs withsome prospectofmobility.These younger

444

This content downloaded from 164.41.232.88 on Mon, 22 Feb 2016 18:28:23 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Spring1987 / SIGNS

and detailedinterestin their

women,though,have added a professional

for

the

work

of

a

felt

to

responsibility

kinship.7

jobs

tasks,familyhistoriesand

Althoughmen rarelytookon anykin-work

liferevealedthatkinswomenoftennegotiated

accountsof contemporary

and gift-buying

hosting,food-preparation,

amongthemselves,alternating

entire

task

sometimes

clusters

to one woman.

ceding

responsibilities-or

was

or

tasks

related

to

on

clearly

Taking

ceding

acquiringor divesting

oneselfof power withinkin networks,but womenvariedin theirinterforexample,

pretationof the meaningof thispower. Cetta Longhinotti,

reliedon the"familyChristmasdinner"as a symbolofhercentralkinship

withherdaughter-in-law

roleand was involvedinpainfulnegotiations

over

the issue: "Last year she insisted-this is touchy.She doesn't want to

spend the holidaydinnertogether.So lastyearwe wentthere.But I still

had mydinnerthe nextday ... I made a big dinneron ChristmasDay,

regardlessof who's coming-candles on the table, the whole routine..I

decoratethe house myselftoo . .. well, I just feelthatthe timewillcome

when maybe I won't feel like cookinga big dinner-she should take

advantageof the factthatI feel like doing it now." Pina Meraviglia,in

forceofthedevelopmentalcycle

contrast,was saddenedbythecentripetal

butwas unworriedaboutthepowerdynamicsinvolvedin hernegotiations

withdaughters-and mother-in-law

over holidaycelebrations.

Kin workis notjust a matterofpoweramongwomenbut also ofthe

mediationofpowerrepresentedbyhouseholdunits.8

Womenoftenchoose

to minimizestatusclaims in theirkin workand to include numbersof

sisterAnna,for

householdsundertherubricoffamily.CettaLonghinotti's

manwhoseparentshaveconsiderable

example,is marriedtoa professional

economicresources,whileJoeand Cetta have low incomesand no other

kin.Cettaand Annaremainclose,talkon thephoneseveraltimesa

well-off

week, and assisttheiradult children,dividedby distanceand economic

status,in remainingunitedas cousins.

Finally,women perceivedhousework,child care, marketlabor, the

care ofthe elderly,and theworkofkinshipas competingresponsibilities.

Kin workwas a unique category,however,because it was unlabeledand

because women feltthey could either cede some tasks to kinswomen

and/orcouldcutthembackseverely.Womenvariouslycitedthepressures

ofmarketlabor,theneeds oftheelderly,and theirowndesiresforfreedom

7

Clearly,manywomendo, in fact,discusstheirpaid laborwithwillingnessand clarity.

The point here is that there are opposing gender tendenciesin an identicalinterview

situation,tendenciesthatare explicablein termsofboththe materialrealitiesand current

culturalconstructions

of gender.

8 Papanekhas rightly

focusedon women'sunacknowledged

familystatusproduction,but

whatis conceivedofas "family"

shifts

and varies(Hanna Papanek,"FamilyStatusProduction:

The 'Work'and 'Non-Work'of Women," Signs4, no. 4 [Summer1979]: 775-81).

445

This content downloaded from 164.41.232.88 on Mon, 22 Feb 2016 18:28:23 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

di Leonirdo / THE WORK OF KINSHIP

and job enrichment

as reasonsforcuttingback Christmascardlists,organized holidaygatherings,multifamily

dinners,letters,visits,and phone

calls. They expressedguiltand defensivenessabout thiscutbackprocess

about theirfailuresto keep familiesclose throughconand, particularly,

stantcontactand abouttheirfailurestocreateperfectholidaycelebrations.

Cetta Longhinotti,duringthe periodwhen she was visitingher elderly

mothereveryweekendin additionto workinga full-time

job, said ofher

grownchildren,"I'd havethewholeganghereoncea month,butI've been

so busythatI haven'tdone thatforaboutsixmonths."AndPina Meraviglia

lamentedherinsufficient

workon familyChristmases,"I wishI had really

made it traditional. . . like mysister-in-law

has special stories."

Kin work,then,takesplace in an arena characterizedsimultaneously

Like housework

bycooperationand competition,

byguiltand gratification.

and childcare, it is women'swork,withthe same lackofclear-cutagreement concerningits proper components:How oftenshould sheets be

changed?When shouldchildrenbe toilettrained?Shouldan auntsend a

niece a birthdaypresent?Unlikehouseworkand childcare,however,kin

work,takingplace acrosstheboundariesofnormative

households,is as yet

unlabeled and has no retinueof expertsprescribingits correctforms.

have muchto sayabout

Neitherhome economistsnorchildpsychologists

nieces' birthdaypresents.Kin workis thusmoreeasilycut back without

On the otherhand,the resultsofkinwork-frequent

social interference.

kincontactand feelingsofintimacy-arethe subjectofconsiderablecultural manipulationas indicatorsof familyhappiness. Thus, women in

expressedovercuttingback

generalare subjectto theguiltmyinformants

kin-workactivities.

to theresultsofwomen'skin

referred

Althoughmanyofmyinformants

work-cross-householdkin contactsand attendantritualgatherings-as

I suggestthatin factthisphenomenonis

particularlyItalian-American,

ofAmericankinship.We thinkofkin-work

taskssuch

broadlycharacteristic

forholidaycardlists,and

as the preparationofritualfeasts,responsibility

forcooking,

giftbuyingas extensionsofwomen'sdomesticresponsibilities

consumption,and nurturance.Americanmen in generaldo not take on

thesetasksanymorethantheydo houseworkandchildcare-and probably

less, as thesetaskshave notyetbeen thesubjectofintensepublicdebate.

Andmyinformants'

on kinship

genderbreakdowninrelativearticulateness

and workplacethemes reflectsthe stillprevalentoccupationalsegregation-most women cannotfindjobs thatprovideenoughpay, status,or

promotionpossibilitiesto make them worthfocusingon-as well as

The commonrecogniwomen'sperceivedpowerwithinkinshipnetworks.

tionofthatpoweris reflectedin SelmaGreenberg'sbookon nonsexistchild

rearing.Greenbergcalls mothers"press agents"who sponsorrelations

between theirown childrenand other relatives;she advises a mother

446

This content downloaded from 164.41.232.88 on Mon, 22 Feb 2016 18:28:23 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Spring1987 / SIGNS

to deny those kin access to her

whose relativestreather disrespectfully

children.9

Kin workis a salientconceptin otherpartsofthe developedworldas

well. Larissa Adler Lomnitzand Marisol Perez Lizaur have foundthat

"centralizingwomen" are responsibleforthese tasksand forcommunicating "familyideology" among upper-classfamiliesin Mexico City.

MatthewsHamabata, in his studyof upper-classfamiliesin Japan,has

foundthatwomen's kin workinvolveskey financialtransactions.Sylvia

JunkoYanagisakodiscoveredthat,amongruralJapanesemigrantsto the

was assignedto womenas

UnitedStates,themaintenanceofkinnetworks

the migrantsadopted the Americanideologyofthe independentnuclear

familyhousehold. Maila StivensnotesthaturbanAustralianhousewives'

kintiesand kinideology"transcendwomen'sisolationindomesticunits."10

This is notto say thatculturalconceptionsofappropriatekinworkdo

notvary,even withinthe UnitedStates.Carol B. Stackdocumentsinstitutionalized fictivekinshipand concomitantreciprocitynetworksamong

impoverishedblack Americanwomen. Women in populationscharacterizedby intensefeelingsofethnicidentitymayfeelboundto emphasize

particularoccasions-Saint Patrick'sor Columbus Day-with organized

as

familyfeasts.These constructs

maybe mediatedby religiousaffiliation,

in the differing

emphaseson Fridayor SundayfamilydinnersamongJews

and Christians.Thus the personnelinvolvedand the amountand kindof

labor considerednecessaryforthe satisfactory

ofparticular

performance

kin-worktasksare likelyto be culturallyconstructed."But while the kin

and quasi-kinuniversesand the ritualcalendarmayvaryamongwomen

theirgeneralresponsibility

formaintaining

accordingto race or ethnicity,

kin linksand ritualobservancesdoes not.

As kinworkis notan ethnicor racialphenomenon,neitheris it linked

9 Selma Greenberg,Rightfromthe Start:A Guide to NonsexistChild Rearing(Boston:

Houghton MifflinCo., 1978), 147. Anotherexample of indirectsupportforkin work's

mathstudents,whichfoundthata major

genderedexistenceis a recentstudyofuniversity

reason forwomen's failureto pursue careers in mathematicswas the pressureof family

involvement.Compare David Maines et al., Social Processes of Sex Differentiation

in

Mathematics(Washington,D.C.: NationalInstituteof Education,1981).

10Larissa Adler Lomnitzand Marisol P6rez Lizaur, "The Historyof a Mexican Urban

Family,"Journalof FamilyHistory3, no. 4 (1978): 392-409, esp. 398; MatthewsHambata,

For Love and Power: FamilyBusinessin Japan (Chicago: Universityof Chicago Press, in

press);SylviaJunkoYanagisako,"Two ProcessesofChangein Japanese-American

Kinship,"

JournalofAnthropologicalResearch31 (1975): 196-224; Maila Stivens,"Womenand Their

Kin: Kin, Class and Solidarityin a Middle-ClassSuburbof Sydney,Australia,"in Women

United,Women Divided, ed. PatriciaCaplan and JanetM. Bujra (Bloomington:Indiana

UniversityPress, 1979), 157-84.

" Carol B. Stack,All Our Kin: Strategiesfor Survivalin a BlackCommunity

(New York:

Harper& Row, 1974). These culturalconstructions

may,however,varywithinethnic/racial

populationsas well.

447

This content downloaded from 164.41.232.88 on Mon, 22 Feb 2016 18:28:23 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

di Leonardo / THE WORK OF KINSHIP

on Americanfamilylifestill

onlyto one social class. Some commentators

reflectthe influenceofworkdone in Englandin the 1950sand 1960s (by

ElizabethBottand byPeterWillmottand MichaelYoung)intheirassumpfamiliesare close and extended,whilethe middle

tionthatworking-class

classsubstitutes

friends(oranomie)forfamily.Othersreflecttheprevalent

normiddlefamilypessimismin theirpresumptionthatneitherworkingclassfamilieshave extendedkincontact.'2

Insofaras kincontactdependson

residentialproximity,

thelargereconomy'sshiftswillinfluenceparticular

groups'experiences.Factoryworkers,close to kin or not, are likelyto

disperse when plants shut down or relocate. Small businesspeopleor

independentprofessionalsmay,however,remainresidentin particular

to kin-forgenerations,

areas-and thusmaintainproximity

whileprofessionalemployeesoflargefirmsrelocateat theirfirms'

behest.Thispattern

obtainedamongmyinformants.

kincontactcan be and is effected

In anyevent,cross-household

at long

distance throughletters,cards, phone calls, and holidayand vacation

visits. The formand functionsof contact,however,varyaccordingto

economicresources.Stackand BrettWilliamsofferrichaccountsof kin

networks

Chicanofarmworkers

amongpoorblacksand migrant

functioning

to provideemotionalsupport,labor,commodity,and cash exchange- a

Far

funeralvisit,helpwithlaundry,thegiftofa dressorpiece offurniture.'3

in degree are exchangessuch as the loan ofa vacationhome, a

different

boatingtrip,or the provisionof freeprofessionalservicesmultifamily

The pointis

examplesfromthe kinnetworksofmywealthierinformants.

thathouseholds,as labor-and income-pooling

units,whatevertheirrelativewealth,are somewhatporousin relationto otherswithwhose members theyshare kin or quasi-kinties. We do not reallyknowhow class

differences

operatein thisrealm;it is possiblethattheydo so largelyin

termsofideology.It maybe, as David Schneiderand RaymondT. Smith

and theverypoorare moreopen in recognizing

suggest,thatthe affluent

12

Elizabeth Bott, Familyand Social Network,2d ed. (New York: Free Press, 1971);

MichaelYoungand PeterWillmott,Familyand Kinshipin East London(London:Routledge

& KeganPaul, 1957),and Familyand Class ina LondonSuburb(London:Routledge& Kegan

are HerbertGans, The Urban

Paul, 1960). Classic studiesthatpresumethisclass difference

Villagers:Groupand Class intheLifeofItalian-Americans

(New York:Free Press,1962);and

Mirra Komarovsky,Blue-Collar Marriage (New York: Random House, 1962). A recent

example is Ilene Philipson,"HeterosexualAntagonismsand the Politicsof Mothering,"

SocialistReview12, no. 6 (November-December1982):55-77. EdwardShorter,TheMaking

oftheModernFamily(New York:BasicBooks,1975),epitomizesthepessimismofthe"family

sentiments"school. See also MaryLyndonShanley,"The Historyofthe Familyin Modern

England: Review Essay," Signs4, no. 4 (Summer1979): 740-50.

13

Stack;and BrettWilliams,"The TripTakesUs: ChicanoMigrantstothePrairie"(Ph.D.

diss., Universityof Illinoisat Urbana-Champaign,

1975).

448

This content downloaded from 164.41.232.88 on Mon, 22 Feb 2016 18:28:23 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Spring1987 / SIGNS

themselvesas

necessaryeconomicties to kinthanare thosewho identify

middle class.'4

Recognizingthatkinworkis genderratherthanclassbased allowsus to

see women'skinnetworksamongall groups,notjust amongworking-class

and impoverishedwomenin industrializedsocieties.This recognitionin

turnclarifiesour understanding

of the privilegesand limitsof women's

womencan "buy out" of

varyingaccess to economicresources.Affluent

housework,child care-and even some kin-workresponsibilities.But

they,like all women,are ultimately

responsible,and subjectto bothguilt

and blame,as theadministrators

ofhome,children,andkinnetwork.Even

thewealthiestwomenmustnegotiatethetimingandvenueofholidaysand

otherfamilyritualswiththeirkinswomen.It maybe thatkinworkis the

corewomen'sworkcategoryinwhichall womencooperate,whilewomen's

perceptionsof the appropriatenessof cooperationforhousework,child

care, and the care ofthe elderlyvariesby race,class, region,and generation.

But kinworkis notnecessarilyan appropriatecategoryoflabor,much

less genderedlabor,in all societies.In manysmall-scalesocieties,kinship

is the majororganizingprincipleofall social life,and all contactsare by

definition

kincontacts.'5

One cannot,therefore,

speakoflaborthatdoes not

involvekin. In the United States, kin workas a separable categoryof

in concertwiththe ideological

genderedlabor perhapsarose historically

and materialconstructsof the moralmother/cult

of domesticity

and the

in the eighteenth

privatizedfamilyduringthe courseofindustrialization

and nineteenthcenturies.These phenomenaareconnectedtotheincrease

in the ubiquityofproductiveoccupationsfor menthatare notorganized

throughkinship.This includes the demise of the familyfarmwith the

and rural-urban

thedeclineoffamcapitalizationofagriculture

migration;

in factoriesas firmsgrew,ended childlabor,and began to

ilyrecruitment

assertbureaucratizedformsofcontrol;thedeclineofartisanallaborand of

smallentrepreneurial

enterprisesas largefirmstookgreaterand greater

sharesofthecommoditymarket;thedeclineofthefamilyfirmas corporations-and theirmanagerialworkforces-grewbeyondthe capacitiesof

individualfamiliesto provisionthem;and, finally,

the riseofcivilservice

bureaucraciesand public pressureagainstnepotism.'6

David Schneiderand RaymondT. Smith,Class Differences

and Sex Rolesin American

Kinshipand FamilyStructure(EnglewoodCliffs,N.J.: Prentice-Hall,Inc., 1973),esp. 27.

15See NelsonGraburn,ed.,

Readingsin Kinshipand Social Structure(New York:Harper

& Row, 1971), esp. 3-4.

16 The moralmother/cult

ofdomesticity

is analyzedin BarbaraWelter,"The CultofTrue

Womanhood,1820-1860,"AmericanQuarterly18, no. 2 (Summer1966): 151-74; Nancy

Cott, The Bonds of Womanhood:"Women'sSphere" in New England, 1780-1835 (New

14

449

This content downloaded from 164.41.232.88 on Mon, 22 Feb 2016 18:28:23 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

di Leonardo

/ THE WORK OF KINSHIP

workedalongsideofnon-kin,

As menincreasingly

andas theideologyof

for

accepted,perhapstheresponsibility

separatesphereswas increasingly

kinmaintenance,likethatforchildrearing,becamegender-focused.

Ryan

pointsout that"built into the updated familyeconomy. . . was a new

Thisvoluntarism,

measureofvoluntarism."

though,"perceivedas theshift

to domesticaffection,"

also signaledthe riseof

frompatriarchalauthority

forfamily

life.Justas the"idea offatherhood

women'smoralresponsibility

itselfseemed almost to witheraway" so did male involvementin the

forkindredlapse.'7

responsibility

With postbellum economic growth and geographic movement,

women'snew kinburdeninvolvedincreasingamountsoftimeand labor.

The ubiquity of lengthyvisits and of frequentletter-writing

among

womenatteststo this.And forvisitorsand forthose

nineteenth-century

who were residentiallyproximate,the continuingcommonalitiesof

women'sdomesticlaborallowedforkindsofworksharing-nursing,childdifferentikeeping,cooking,cleaning-that men,withtheirincreasingly

ated and controlledactivities,probablycould notmaintain.This is notto

male productiveworkdid notcontinue;myown

saythatsome kin-related

data,forinstance,showkininvolvement

amongsmallbusinessmenin the

present. It is, instead,to suggesta generaltrendin materiallifeand a

culturalshiftthatinfluencedeven thosewhose productiveand kin lives

remainedcommingled.Yanagisakohas distinguished

betweenthe realms

to anthropology's

ofdomesticand publickinshipin orderto drawattention

relatively"thindescriptions"ofthe domestic(female)domain.Usingher

typology,we mightsay thatkinworkas genderedlaborcomes intoexistencewithinthe domesticdomainwiththerelativeerasureofthedomain

ofpublic, male kinship."8

Press, 1977);and RuthBloch,"AmericanFeminineIdeals in

Haven, Conn.: Yale University

Transition:The Rise ofthe MoralMother,1785-1815,"FeministStudies4, no. 2 (June1978):

shiftintheUnitedStatesis based on

ofthegeneralpolitical-economic

101-26.The description

HarryBraverman,Labor and MonopolyCapital: The DegradationofWorkin theTwentieth

and

Century(New York:MonthlyReviewPress,1974);PeterDobkinHall, "FamilyStructure

EconomicOrganization:MassachusettsMerchants,1700-1850,"in Familyand Kinin Urban

Communities,

1700-1950,ed. TamaraK. Hareven(New York:NewViewpoints,1977),38-61;

Michael Anderson,"Family,Household and the IndustrialRevolution,"in The American

Familyin Social-HistoricalPerspective,ed. MichaelGordon(New York:St. Martin'sPress,

1978),38-50; Tamara K. Hareven,Amoskeag:Lifeand Workin an AmericanFactoryCity

(New York:PantheonBooks, 1978); RichardEdwards,ContestedTerrain:The TransformationoftheWorkplacein theTwentieth

Century(New York:Basic Books,1979); MaryRyan,

The Cradle of the Middle Class: The Family in Oneida County,New York, 1790-1865

(Cambridge:Cambridge UniversityPress, 1981); Alice Kessler-Harris,Out to Work: A

Press,

Historyof Wage-earningWomenin the UnitedStates(New York:OxfordUniversity

1982).

17

Ryan,231-32.

18

SylviaJunkoYanagisako,"Familyand Household:The AnalysisofDomesticGroups,"

8 (1979): 161-205.

Annual Reviewof Anthropology

450

This content downloaded from 164.41.232.88 on Mon, 22 Feb 2016 18:28:23 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Spring1987 / SIGNS

Whetheror notthisproposedhistoricalmodelbears up underfurther

research,the questionremains,Why do womendo kinwork?However

materialfactorsmay shape activities,theydo not determinehow individuals may perceive them. And in consideringissues of motivation,of

intention,of the culturalconstructionof kin work,we returnto the

inrecentfeminist

altruismversusself-interest

theory.Consider

dichotomy

weavers

theepigraphstothisarticle.Arewomenkinworkersthenurturant

ofthe Gilliganquotation,or victims,likethefed-upwomanwhowritesto

complainto Ann Landers?That is, are we to see kinworkas yetanother

exampleof"women'sculture"thattakesthe care ofothersas its primary

desideratum?Or are we to see kinworkas anotherwayin whichmen,the

economy,and the stateextractlaborfromwomenwithouta fairreturn?

And how do women themselvessee theirkinworkand its place in their

lives?

As I have indicatedabove, I believe that it is the creationof the

self-interest/altruism

dichotomythat is itselfthe problem here. My

like mostAmericanwomen,accepted theirprimary

women informants,

forhouseworkand thecare ofdependentchildren.Despite

responsibility

two major waves of feministactivismin this century,the genderingof

certaincategoriesof unpaid labor is stilllargelyunaltered.These work

withsome women'slaborforcecommitclearlyinterfere

responsibilities

womenare simply

mentsat certainlife-cycle

stages;but,moreimportant,

discriminatedagainstin the labor marketand rarelyare able to achieve

wage and statusparitywithmen ofthe same age, race, class, and educationalbackground.19

as formostAmericanwomen, the

Thus formy women informants,

domesticdomainis notonlyan arenainwhichmuchunpaidlabormustbe

undertakenbut also a realm in whichone may attemptto gain human

satisfactions-andpower-not availablein the labormarket.Anthropoloon the

gistsJaneCollierand Louise Lampherehave writtencompellingly

which

and

economic

in

structures

varyingkinship

may shape

ways

women's competitionor cooperationwith one another in domestic

domains.20Feminists consideringWestern women and familieshave

in termsofhusband-wife

relationsor

lookedat theissue ofpowerprimarily

and

children.

If

we

relations

between

adoptCollier

parents

psychological

is notonly

we

see

that

kin

work

and Lamphere'sbroadercanvas,though,

men

and

children

benefit

but

also

from

which

labor that

women'slabor

womenundertakeinordertocreateobligationsin menand childrenand to

strugglewithher

gainpowerover one another.Thus Cetta Longhinotti's

venue

of

Christmas

dinner

over

the

is

notjust about a

daughter-in-law

19See Donald J.Treimanand Heidi I. Hartmann,eds., Women,Workand Wages:

Equal

Pay for Jobsof Equal Value (Washington,D.C.: NationalAcademyPress, 1981).

20Lamphere(n. 4 above); JaneFishburneCollier,"Womenin Politics,"in Rosaldoand

Lamphere,eds. (n. 4 above), 89-96.

451

This content downloaded from 164.41.232.88 on Mon, 22 Feb 2016 18:28:23 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

di Leonardo / THE WORK OF KINSHIP

overaltruism,itis alsoaboutthecreationoffutureobligations.

competition

oftheirchildren'sfriendship

with

AndthusCetta'sand Anna'ssponsorship

and a cooperativemeansofgaining

each otheris bothan act ofnurturance

power over thosechildren.

thoseofmyinformants

Althoughthiswas not a clear-cutdistinction,

tendedto be mostinvestedin kin

who were moreexplicitlyantifeminist

shift

historical

towardgreaterautonomyfor

work.Giventheoverwhelming

youngergenerationsand the witheringof children'sfinancialand labor

was in mostcases tragically

obligationsto theirparents,thisinvestment

doomed. Cetta Longhinotti,forexample,had repaid her own mother's

devotionwith extensivehome nursingduringthe mother'slast years.

Given Cetta's generalfailureto directher adultchildrenin work,marital

choice, religiousworship,or even frequencyofvisits,she is unlikelyto

receive such care fromthemwhen she is older.

lensthusrevealsthecloserelationsbetweenaltruismand

The kin-work

in women'sactions.As economistsNancyFolbre and Heidi

self-interest

Hartmannpointout, we have inheriteda Westernintellectualtradition

thatboth dichotomizesthe domesticand public domainsand associates

to see self-interest

in

themon exclusiveaxes such thatwe findit difficult

the home and altruismin the workplace.21But why,in fact,have women

foughtforbetterjobs if not, in part, to supporttheirchildren?These

ofwomen's

beds thatwarpourunderstanding

dichotomiesare Procrustean

and "self-interest"

are cultural

livesbothat homeand at work."Altruism"

thatare not necessarilymutuallyexclusive,and we forget

constructions

thisto our peril.

unacThe conceptofkinworkhelps to bringintofocusa heretofore

knowledgedarrayof tasksthatis culturallyassignedto womenin industrializedsocieties.At the same time,thisconcept,embodyingnotionsof

bothlove and workand crossingtheboundariesofhouseholds,helpsus to

and commudebateson women'swork,family,

reflecton currentfeminist

ofthesephenomenaand womnity.We newlysee boththeinterrelations

thoseinterrelations.

en's rolesin creatingand maintaining

Revealingthe

conceiveas love and consideractuallaborembodiedinwhatwe culturally

theself-interest/alingthepoliticaluses ofthislaborhelpsto deconstruct

truismdichotomyand to connectmore closelywomen's domesticand

lives.

labor-force

The truevalue ofthe concept,however,remainsto be testedthrough

researchon gender, kinship,and

furtherhistoricaland contemporary

labor.We need to assessthesuggestionthatgenderedkinworkemergesin

concertwiththe capitalistdevelopmentprocess;to probe the historical

recordforwomen'sand men'svaryingand changingconceptionsofit;and

21

Nancy Folbre and Heidi I. Hartmann,"The Rhetoricof Self-Interest:Selfishness,

and Genderin EconomicTheory,"in TheConsequencesofEconomicRhetoric,ed.

Altruism,

Press,forthcoming).

ArjoKlamerand Donald McCloskey(New York:CambridgeUniversity

452

This content downloaded from 164.41.232.88 on Mon, 22 Feb 2016 18:28:23 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Spring1987 / SIGNS

and material

to researchthe currentrange of its culturalconstructions

realities.We knowthathouseholdboundariesare moreporousthanwe

had thought-buttheyare undoubtedlydifferentially

porous,and thisis

whatwe need to specify.We need, in particular,to assess therelationsof

to

changinglaborprocesses,residentialpatterns,and theuse oftechnology

changingkinwork.

Alteringthe values attachedto this particularset of women's tasks

will be as difficult

as are the housework,child-care,and occupationalresearchin theselatterareas is

segregationstruggles.Butjust as feminist

and cumulative,so researching

kinworkshouldhelp us to

complementary

piece togetherthe home, work,and public-lifelandscape-to see the

femaleworldofcardsand holidaysas itis constructed

and livedwithinthe

changingpoliticaleconomy.How femalethatworldis to remain,and what

itwouldlooklikeifitwerenotsex-segregated,

are questionswe cannotyet

answer.

DepartmentofAnthropology

Yale University

453

This content downloaded from 164.41.232.88 on Mon, 22 Feb 2016 18:28:23 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- A Slave Family in ArkansasDocument22 pagesA Slave Family in Arkansasromandaylamy100% (1)

- Playful Homeschool Planner - FULLDocument13 pagesPlayful Homeschool Planner - FULLamandalecuyer88No ratings yet

- Family Abolition: Capitalism and the Communizing of CareFrom EverandFamily Abolition: Capitalism and the Communizing of CareRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Radical America - Vol 5 No 4 - 1971 - July AugustDocument124 pagesRadical America - Vol 5 No 4 - 1971 - July AugustIsaacSilver100% (1)

- (123doc) - Toefl-Reading-Comprehension-Test-41Document8 pages(123doc) - Toefl-Reading-Comprehension-Test-41Steve XNo ratings yet

- The Social Construction of Black Feminist ThoughtDocument30 pagesThe Social Construction of Black Feminist Thoughtdocbrown85100% (2)

- Transforming The Race-Mother-Motherhood and Eugenics in British Modernism-Emily HarbinDocument256 pagesTransforming The Race-Mother-Motherhood and Eugenics in British Modernism-Emily HarbinzepolkNo ratings yet

- Where Men Are Wives and Mothers Rule: Santería Ritual Practices and Their Gender ImplicationsDocument199 pagesWhere Men Are Wives and Mothers Rule: Santería Ritual Practices and Their Gender ImplicationsMarinaNo ratings yet

- Postmodernism and Gender Relations in Feminist TheoryDocument24 pagesPostmodernism and Gender Relations in Feminist Theorypanos stebNo ratings yet

- Methods of Recording Retruded Contact Position in Dentate PatientsDocument15 pagesMethods of Recording Retruded Contact Position in Dentate PatientsYossr MokhtarNo ratings yet

- Feminist Generations: The Persistence of the Radical Women's MovementFrom EverandFeminist Generations: The Persistence of the Radical Women's MovementRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Alice Echols - Cultural FeminismDocument21 pagesAlice Echols - Cultural FeminismbongofuryNo ratings yet

- Disposable Domestics: Immigrant Women Workers in the Global EconomyFrom EverandDisposable Domestics: Immigrant Women Workers in the Global EconomyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Abolition Feminisms Vol. 2: Feminist Ruptures against the Carceral StateFrom EverandAbolition Feminisms Vol. 2: Feminist Ruptures against the Carceral StateAlisa BierriaNo ratings yet

- Unruly Equality: U.S. Anarchism in the Twentieth CenturyFrom EverandUnruly Equality: U.S. Anarchism in the Twentieth CenturyRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- ROSALDO, M. The Use and Abuse of Anthropology. Reflections On Feminism and Cross - CulturalDocument30 pagesROSALDO, M. The Use and Abuse of Anthropology. Reflections On Feminism and Cross - CulturalFlorencia Rodríguez100% (1)

- IEC ShipsDocument6 pagesIEC ShipsdimitaringNo ratings yet

- A Revolutionary Faith: Liberation Theology Between Public Religion and Public ReasonFrom EverandA Revolutionary Faith: Liberation Theology Between Public Religion and Public ReasonNo ratings yet

- Arens - Auditing and Assurance Services 15e-2Document17 pagesArens - Auditing and Assurance Services 15e-2Magdaline ChuaNo ratings yet

- Feminist and International Organizations Ann TicknerDocument29 pagesFeminist and International Organizations Ann Ticknerbelanyegas50% (2)

- Funding Feminism: Monied Women, Philanthropy, and the Women’s Movement, 1870–1967From EverandFunding Feminism: Monied Women, Philanthropy, and the Women’s Movement, 1870–1967No ratings yet

- Conceiving the Future: Pronatalism, Reproduction, and the Family in the United States, 1890-1938From EverandConceiving the Future: Pronatalism, Reproduction, and the Family in the United States, 1890-1938Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Interpreting the Internet: Feminist and Queer Counterpublics in Latin AmericaFrom EverandInterpreting the Internet: Feminist and Queer Counterpublics in Latin AmericaNo ratings yet

- Making Livable Worlds: Afro-Puerto Rican Women Building Environmental JusticeFrom EverandMaking Livable Worlds: Afro-Puerto Rican Women Building Environmental JusticeNo ratings yet

- Kahneman & Tversky Origin of Behavioural EconomicsDocument25 pagesKahneman & Tversky Origin of Behavioural EconomicsIan Hughes100% (1)

- Laboratory of Deficiency: Sterilization and Confinement in California, 1900–1950sFrom EverandLaboratory of Deficiency: Sterilization and Confinement in California, 1900–1950sNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 - Organization Structure & CultureDocument63 pagesChapter 3 - Organization Structure & CultureDr. Shuva GhoshNo ratings yet

- Strangers At Home: Amish and Mennonite Women in HistoryFrom EverandStrangers At Home: Amish and Mennonite Women in HistoryNo ratings yet

- Fashioning Character: Style, Performance, and Identity in Contemporary American LiteratureFrom EverandFashioning Character: Style, Performance, and Identity in Contemporary American LiteratureNo ratings yet

- Neoliberalism, Interrupted: Social Change and Contested Governance in Contemporary Latin AmericaFrom EverandNeoliberalism, Interrupted: Social Change and Contested Governance in Contemporary Latin AmericaNo ratings yet

- Mexican New York: Transnational Lives of New ImmigrantsFrom EverandMexican New York: Transnational Lives of New ImmigrantsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Engendering Democracy in Brazil: Women's Movements in Transition PoliticsFrom EverandEngendering Democracy in Brazil: Women's Movements in Transition PoliticsNo ratings yet

- Women's Culture and Lesbian Feminist Activism - A Reconsideration of Cultural FeminismDocument31 pagesWomen's Culture and Lesbian Feminist Activism - A Reconsideration of Cultural FeminismAleksandar RadulovicNo ratings yet

- The Sixteenth Century JournalDocument12 pagesThe Sixteenth Century Journalapi-278489886No ratings yet

- Adrienne Rich - Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian ExistenceDocument30 pagesAdrienne Rich - Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian ExistenceTomás EstefóNo ratings yet

- In Darkness and SecrecyDocument4 pagesIn Darkness and SecrecyDaniel López Yáñez100% (1)

- The Woman Fantastic in Contemporary American Media CultureFrom EverandThe Woman Fantastic in Contemporary American Media CultureRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Fourierist Communities of Reform The Social Networks of Nineteenth Century Female Reformers Amy Hart Full ChapterDocument62 pagesFourierist Communities of Reform The Social Networks of Nineteenth Century Female Reformers Amy Hart Full Chaptercatherine.morris903100% (10)

- Activism and the American Novel: Religion and Resistance in Fiction by Women of ColorFrom EverandActivism and the American Novel: Religion and Resistance in Fiction by Women of ColorNo ratings yet

- The Politics of Love: Sex Reformers and the NonhumanFrom EverandThe Politics of Love: Sex Reformers and the NonhumanNo ratings yet

- Queer Argentina - Movement Towards The Closet in A Global Time (2017, Palgrave Macmillan US)Document207 pagesQueer Argentina - Movement Towards The Closet in A Global Time (2017, Palgrave Macmillan US)grandebizinNo ratings yet

- Liberation in Print: Feminist Periodicals and Social Movement IdentityFrom EverandLiberation in Print: Feminist Periodicals and Social Movement IdentityRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Feminine Singularity: The Politics of Subjectivity in Nineteenth-Century LiteratureFrom EverandFeminine Singularity: The Politics of Subjectivity in Nineteenth-Century LiteratureRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Public Religions in the Future World: Postsecularism and UtopiaFrom EverandPublic Religions in the Future World: Postsecularism and UtopiaNo ratings yet

- Activism in the Name of God: Religion and Black Feminist Public Intellectuals from the Nineteenth Century to the PresentFrom EverandActivism in the Name of God: Religion and Black Feminist Public Intellectuals from the Nineteenth Century to the PresentJami L. CarlacioNo ratings yet

- American Sociological Association Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Contemporary SociologyDocument5 pagesAmerican Sociological Association Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Contemporary SociologyMiodrag MijatovicNo ratings yet

- Redeeming La Raza Transborder Modernity Race Respectability and Rights Gabriela Gonzalez All ChapterDocument67 pagesRedeeming La Raza Transborder Modernity Race Respectability and Rights Gabriela Gonzalez All Chaptersusan.catanzarite506100% (13)

- Feminism as Life's Work: Four Modern American Women through Two World WarsFrom EverandFeminism as Life's Work: Four Modern American Women through Two World WarsNo ratings yet

- Finding Feminism: Millennial Activists and the Unfinished Gender RevolutionFrom EverandFinding Feminism: Millennial Activists and the Unfinished Gender RevolutionNo ratings yet

- Silk Stockings and Socialism: Philadelphia's Radical Hosiery Workers from the Jazz Age to the New DealFrom EverandSilk Stockings and Socialism: Philadelphia's Radical Hosiery Workers from the Jazz Age to the New DealNo ratings yet

- Fashioning Politics and Protests New Visual Cultures of Feminism in The United States Emily L Newman Full ChapterDocument67 pagesFashioning Politics and Protests New Visual Cultures of Feminism in The United States Emily L Newman Full Chapterantonia.connor789100% (17)

- BLACKWOOD - Gender, SExuality in Certain North AmeDocument17 pagesBLACKWOOD - Gender, SExuality in Certain North AmeAlessandra KafkaNo ratings yet

- Alone at the Altar: Single Women and Devotion in Guatemala, 1670-1870From EverandAlone at the Altar: Single Women and Devotion in Guatemala, 1670-1870No ratings yet

- Gendered Paradoxes: Women's Movements, State Restructuring, and Global Development in EcuadorFrom EverandGendered Paradoxes: Women's Movements, State Restructuring, and Global Development in EcuadorNo ratings yet

- The Enclosed Garden: Women and Community in the Evangelical South, 1830-1900From EverandThe Enclosed Garden: Women and Community in the Evangelical South, 1830-1900No ratings yet

- Seattle in Coalition: Multiracial Alliances, Labor Politics, and Transnational Activism in the Pacific Northwest, 1970–1999From EverandSeattle in Coalition: Multiracial Alliances, Labor Politics, and Transnational Activism in the Pacific Northwest, 1970–1999No ratings yet

- 2011 Annual RVWDocument28 pages2011 Annual RVWNath BaltierraNo ratings yet

- Guatemala's Catholic Revolution: A History of Religious and Social Reform, 1920-1968From EverandGuatemala's Catholic Revolution: A History of Religious and Social Reform, 1920-1968No ratings yet

- Chapter 13 Exercises With AnswerDocument5 pagesChapter 13 Exercises With AnswerTabitha HowardNo ratings yet

- Organizational ConflictDocument22 pagesOrganizational ConflictTannya AlexandraNo ratings yet

- Vendor Information Sheet - LFPR-F-002b Rev. 04Document6 pagesVendor Information Sheet - LFPR-F-002b Rev. 04Chelsea EsparagozaNo ratings yet

- Huawei R4815N1 DatasheetDocument2 pagesHuawei R4815N1 DatasheetBysNo ratings yet

- Ito Na Talaga Yung FinalDocument22 pagesIto Na Talaga Yung FinalJonas Gian Miguel MadarangNo ratings yet

- Harper Independent Distributor Tri FoldDocument2 pagesHarper Independent Distributor Tri FoldYipper ShnipperNo ratings yet

- Pe 03 - Course ModuleDocument42 pagesPe 03 - Course ModuleMARIEL ASINo ratings yet

- The Indonesia National Clean Development Mechanism Strategy StudyDocument223 pagesThe Indonesia National Clean Development Mechanism Strategy StudyGedeBudiSuprayogaNo ratings yet

- Quantitative Methods For Economics and Business Lecture N. 5Document20 pagesQuantitative Methods For Economics and Business Lecture N. 5ghassen msakenNo ratings yet

- Carob-Tree As CO2 Sink in The Carbon MarketDocument5 pagesCarob-Tree As CO2 Sink in The Carbon MarketFayssal KartobiNo ratings yet

- Ricoh IM C2000 IM C2500: Full Colour Multi Function PrinterDocument4 pagesRicoh IM C2000 IM C2500: Full Colour Multi Function PrinterKothapalli ChiranjeeviNo ratings yet

- Linguistics Is Descriptive, Not Prescriptive.: Prescriptive Grammar. Prescriptive Rules Tell You HowDocument2 pagesLinguistics Is Descriptive, Not Prescriptive.: Prescriptive Grammar. Prescriptive Rules Tell You HowMonette Rivera Villanueva100% (1)

- B122 - Tma03Document7 pagesB122 - Tma03Martin SantambrogioNo ratings yet

- Specificities of The Terminology in AfricaDocument2 pagesSpecificities of The Terminology in Africapaddy100% (1)

- Online Extra: "Economists Suffer From Physics Envy"Document2 pagesOnline Extra: "Economists Suffer From Physics Envy"Bisto MasiloNo ratings yet

- Study 107 - The Doctrine of Salvation - Part 8Document2 pagesStudy 107 - The Doctrine of Salvation - Part 8Jason MyersNo ratings yet

- BNF Pos - StockmockDocument14 pagesBNF Pos - StockmockSatish KumarNo ratings yet

- Duavent Drug Study - CunadoDocument3 pagesDuavent Drug Study - CunadoLexa Moreene Cu�adoNo ratings yet

- Test Your Knowledge - Study Session 1Document4 pagesTest Your Knowledge - Study Session 1My KhanhNo ratings yet

- AnticyclonesDocument5 pagesAnticyclonescicileanaNo ratings yet

- Application of Graph Theory in Operations ResearchDocument3 pagesApplication of Graph Theory in Operations ResearchInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology100% (2)

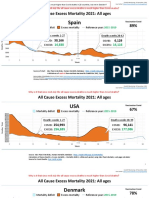

- Countries EXCESS DEATHS All Ages - 15nov2021Document21 pagesCountries EXCESS DEATHS All Ages - 15nov2021robaksNo ratings yet

- Blue Prism Data Sheet - Provisioning A Blue Prism Database ServerDocument5 pagesBlue Prism Data Sheet - Provisioning A Blue Prism Database Serverreddy_vemula_praveenNo ratings yet