Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Crime: White-Collar

Uploaded by

Michael RandolphOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Crime: White-Collar

Uploaded by

Michael RandolphCopyright:

Available Formats

A

N E W

Y O R K

L A W

J O U R N A L

S P E C I A L

S E C T I O N

White-Collar

Crime

www. NYLJ.com

Monday, September 30, 2013

By Benjamin Gruenstein

Benjamin Gruenstein is a partner in Cravath, Swaine &

Moores litigation department. Beth Lipman, a summer

associate, assisted in the preparation of this article.

Agrawal Allays Concerns About

Trade Secret Protection

the defendant completed his prison

term. But in its decision, the courtin

a partially split decisionnoted the limits of the Aleynikov decision and upheld

Agrawals convictions under both the

NSPA and EEA. Although the ultimate significance of the decision remains to be

seen, the caseas well as other developments that have taken place in the year

since Aleynikov was decidedshould

allay some of the concerns expressed

after Aleynikov about the strength of

trade secret rights in the Second Circuit.

Second Circuits 2012 Decision

in Aleynikov

The Aleynikov decision arose from

a fact pattern worthy of a law school

Bigstock

n April 11, 2012, the U.S. Court of

Appeals for the Second Circuit

issued its opinion in United States

v. Aleynikov,1 vacating the Southern District of New York convictions of a former

Goldman Sachs computer programmer

who stole source code related to Goldmans confidential trading system under

the National Stolen Property Act2 (NSPA)

and the Economic Espionage Act3 (EEA).

At the time, commentators expressed

concern that the opinion would severely

limit the ability of prosecutors to enforce

companies trade secrets under the

NSPA and EEA in cases, like Aleynikov,

in which the stolen source code was not

a good intended for resale (the courts

basis for holding that the EEA did not

apply) and was taken by intangible

means (the courts basis for holding

that the NSPA did not apply).

Courtwatchers expected further guidance to arrive in United States v. Agrawal,

a case pending in the Second Circuit at

the time Aleynikov was decided. Like

Aleynikov, Agrawal was an appeal in a

trade secrets case from convictions in

the Southern District of New York under

the NSPA and EEA. The fact patterns of

the two cases were similar, yet different

in ways that could allow the court to

explore the reach of the Aleynikov decision. The Second Circuit did not issue

its decision in Agrawal until last month,

approximately 14 months after the case

was arguedand over 8 months after

Monday, September 30, 2013

exam. In his last day as a computer

programmer at Goldman Sachs, Sergey

Aleynikov stole proprietary source code

for Goldmans high-frequency trading

system by uploading it onto a server in

Germany so that he could later retrieve

it and use it for the benefit of his new

employer, which also sought to develop

such a trading system. Aleynikov was

arrested and ultimately convicted of

violating the EEA (which at the time

criminalized the theft of trade secrets

related to or included in a product that

is produced for or placed in interstate

or foreign commerce) and the NSPA

(which criminalized the interstate transportation of stolen property).

The Second Circuit reversed

Aleynikovs convictions under both

statutes. The computer code, the court

reasoned, was purely intangible property and thus the theft of it by uploading it onto a server in Germany did not

constitute the sort of theft of goods,

wares or merchandise that the NSPA

criminalizes. The court also found no

violation of the EEA, whichat the

time of the decisiononly applied to

products produced for or placed in

interstate or foreign commerce. Goldmans high-frequency trading system, by

contrast, was so valuable that its source

code was not for sale but was for internal use only.4 In a concurring opinion,

Judge Guido Calabresi recognized the

apparent gap in the laws coverage for

invaluable property, and express[ed]

the hope that Congress will return to

the issue and state, in appropriate language, what [he] believe[d] they meant

to make criminal in the EEA.5

Developments in the Wake

of Aleynikov

Within months of the Aleynikov decision, Congress appeared to respond

to Calabresis recommendation and

amended the EEA so as to correct[]

the [Second Circuits] narrow reading

to ensure that our federal criminal laws

adequately address the theft of trade

secrets related to a product or service

used in interstate commerce.6 Congress

passed the Theft of Trade Secrets Clarification Act of 2012 on Dec. 18, 2012,

which expanded the scope of the EEA

from the theft of objects produced

for or placed in interstate or foreign

commerce to those product[s] or

service[s] used in or intended for use

in interstate or foreign commerce.7 The

EEA now covers systems like that of

Goldman Sachs that are used to conduct

trades impacting interstate commerce

even if the systems themselves are not

offered for sale outside the company.

Although the ultimate significance of Agrawal remains to be

seen, the case should allay some

of the concerns expressed after

Aleynikov about the strength

of trade secret rights in the

Second Circuit.

Showing even further support for

strengthened trade secret protection

laws, Congress amended the EEA again

weeks later, increasing the maximum

fines for misappropriating trade secrets

to benefit a foreign government to $5 million for individuals and the greater of $10

million or three times the value of the

stolen trade secrets for organizations.8

Congress also considered additional bills

that would: explicitly cover governmentsponsored hacking within the scope of

the EEA; clarify that trade secrets laws

apply to individuals illicitly accessing

American computers even if they are

never physically present in the United

States; establish the theft of trade secrets

as a predicate offense of the RICO statute9

and provide for a private right of action

by companies against those who steal

their trade secrets.10

At the same time that Congress sought

to clarify the scope of the EEA, the

Obama Administration in February 2013

released its Strategy on Mitigating the

Theft of U.S. Trade Secrets,11 announcing

its intention to make the protection of

trade secrets belonging to U.S. companies a federal law enforcement priority.

And after the Second Circuit reversed

Aleynikovs conviction last year, the

New York County District Attorneys

Office demonstrated its commitment to

prosecuting the theft of trade secrets,

charging Aleynikov himself in state

court with unlawful use of secret scientific material.12 Aleynikov moved to dismiss those claims on double jeopardy

grounds, and that motion was denied

on April 5, 2013. The court noted that

successive federal and state prosecutions for the same conduct are permitted and that the cases were charged

under different statutes.13 That case

appears to be moving forward.14

United States v. Agrawal

Despite hearing argument in the

case in June 2012, the Second Circuit

did not issue its decision in United

States v. Agrawal until Aug. 1, 2013.15

The facts of Agrawal were facially similar to those in Aleynikov, involving the

theft of confidential source code by a

bank programmer for use by his next

employer. Nevertheless, the court, in a

partially split decision, noted two differences that provided the bases to uphold

Agrawals convictions.

First, the court noted that unlike

Aleynikov, the property that Agrawal

had stolen was tangiblereams of

paper containing print-outs of the confidential source code. The court concluded that Agrawals argument challenging

his NSPA convictions failed because it

ignore[d] Aleynikovs emphasis on the

format in which intellectual property is

taken.16 As a result, it was irrelevant

that the code had been in an intangible

form before Agrawal took it from the

offices of his former employer.17 While

the court noted that the distinction

between stealing by printing and stealing by uploading to a server was of little

moment from the perspective of moral

Monday, September 30, 2013

culpability, it held that it nonetheless

makes all the difference for purposes

of the NSPA.18

Second, the court distinguished

Aleynikov on the basis that the government there took the position at trial

that the trading system itself was the

product produced for or placed in

interstate commerce under the EEA, but

in Agrawal the government considered

the traded securities themselves to be

the relevant products (and the source

code to be related to the securities).19

The difference, then, between the two

cases was one of pleading. Judge Rosemary S. Pooler, who served on both

the Aleynikov and Agrawal panels, dissented with regard to the courts EEA

findings, accusing the majority of effectively applying the broader, amended

version of the EEA to the conduct at

issue, despite the fact that the amendments were not retroactive to the earlier conduct.20 Pooler concluded that

even if the traded securities were the

relevant product, it was an impermissible stretch to say that the stolen

code related to those securities; in

any event, however, Pooler found that

the government had actually alleged

that the trading system, and not the

securities, was the relevant product

under the EEA.21

While the decision in Agrawal appears

to place limits on the earlier decision in

Aleynikov, the practical significance of

the decision may actually be narrow.

With respect to the NSPA, the Second

Circuit has clarified that the theft of com-

puter code that has been reduced to

writing or copied to a thumb drive will be

covered by the statute. Of course, while

this may provide a basis for enforcement in some cases, it stands to reason

that most computer code thieveseven

those who were not intentionally trying

to evade the NSPAwould use electronic

means to commit their crime. And, with

respect to the EEA, while the conclusion in Agrawal that prosecutors could

essentially plead around the jurisdiction

defect in Aleynikov is significant, it, of

course, only applies to pre-amendment

conduct and not to any cases brought

in response to conduct after Congress

amendment of the EEA in December

2012. For cases brought under the EEA in

response to conduct after that date, Congress swift legislative action undid the

Second Circuits work in Aleynikov well

before the Agrawal case was decided.

Conclusion

Although Agrawal was released from

prison in November 2012over eight

months before the Second Circuit issued

its decision upholding his convictions

he continues to fight the charges against

him and is now seeking en banc review

of the panels decision. Pending resolution of his petition, Agrawal is the law

of the circuit, and should allay some of

the fears that the Aleynikov decision

signified a weakening in trade secret

protection. And lest there be any doubt

of the governments commitment to

enforcing trade secrets, Congress swift

amendment of the EEA in response to

Aleynikov, as well as the New York County district attorneys decision to prosecute Aleynikov in state court for the

same conduct for which he was charged

federally, provide a strong indication

of the trajectory of enforcement in this

area. As future prosecutions in this area

are likely, courts will have ample opportunity to explore the contours of the

federal statutes protecting trade secrets

and the recent Second Circuit decisions

interpreting them.

1. 676 F.3d 71 (2d Cir. 2012).

2. 18 U.S.C. 2314.

3. 18 U.S.C. 1832.

4. Aleynikov, 676 F.3d at 82.

5. Id. at 83 (Calabresi, J., concurring).

6. Press Release, Statement of Senator Patrick Leahy (Nov.

27, 2012), available at http://www.leahy.senate.gov/press/senate-approves-leahy-bill-to-address-trade-secret-theft.

7. Pub. L. No. 112-236, 126 Stat. 1627 (emphasis added).

8. Foreign and Economic Espionage Penalty Enhancement

Act of 2012, Pub. L. No. 112-269, 126 Stat. 2442.

9. Whitehouse-Graham Discussion Draft, 113th Cong. (2013),

http://www.whitehouse.senate.gov/download/?id=bfff5944bb28-47f8-a309-b5bb3dd729ef.

10. Private Right of Action Against Theft of Trade Secrets

Act of 2013, H.R. 2466, 113th Cong.

11. Administration Strategy on Mitigating the Theft of U.S.

Secrets (2013), available at http://www.whitehouse.gov//sites/

default/files/omb/IPEC/admin_strategy_on_mitigating_the_

theft_of_u.s._trade_secrets.pdf.

12. N.Y. Penal Law 165.07.

13. People v. Aleynikov, No. 04447/2012, slip op. at 16-20

(N.Y. Sup. Ct. April 5, 2013).

14. In his expos on Aleynikov published in this months issue of Vanity Fair, Michael Lewis reported that while the District Attorneys Office offered Aleynikov a plea deal that would

not result in him serving additional jail time, Aleynikovs counsel swiftly rejected it. Michael Lewis, Goldmans Geek Tragedy, Vanity Fair, September 2013, at 312, 360.

15. No. 11-1074-CR, 2013 WL 3942204 (2d Cir. Aug. 1, 2013).

16. Id. at *13.

17. Id. at *14.

18. Id. at *13-15.

19. Id. at *8-10.

20. Id. at *23 (Pooler, J., concurring in part and dissenting

in part).

21. Id. at *24-28 (Pooler, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part).

Reprinted with permission from the September 30, 2013 edition of the NEW

YORK LAW JOURNAL 2012 ALM Media Properties, LLC. All rights reserved.

Further duplication without permission is prohibited. For information, contact 877257-3382 or reprints@alm.com. # 070-10-13-04

You might also like

- Protecting Legitimate Expectations and Estoppel in Scots LawDocument22 pagesProtecting Legitimate Expectations and Estoppel in Scots LawStuart HillNo ratings yet

- Short Summary of Prevention of Corruption ActDocument4 pagesShort Summary of Prevention of Corruption ActMandeep Singh WaliaNo ratings yet

- Reflections On The Goldman IP Theft Saga: Law360, New York (July 17, 2015, 1:16 PM ET)Document3 pagesReflections On The Goldman IP Theft Saga: Law360, New York (July 17, 2015, 1:16 PM ET)api-283774434No ratings yet

- 12 09 26 Preliminary Review of The German Federal Constitutional Court Electronic RecordsDocument7 pages12 09 26 Preliminary Review of The German Federal Constitutional Court Electronic RecordsHuman Rights Alert - NGO (RA)No ratings yet

- Helga M. Glock v. Glock, Inc., 11th Cir. (2015)Document18 pagesHelga M. Glock v. Glock, Inc., 11th Cir. (2015)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Abidor and House: Lost Opportunities To Sync The Border Search Doctrine With Today's TechnologyDocument31 pagesAbidor and House: Lost Opportunities To Sync The Border Search Doctrine With Today's TechnologyNEJCCCNo ratings yet

- United States v. Da-Chuan Zheng, Kuang-Shin Lin, Jing-Li Zhang, David Tsai, Allen Yeung, 768 F.2d 518, 3rd Cir. (1985)Document10 pagesUnited States v. Da-Chuan Zheng, Kuang-Shin Lin, Jing-Li Zhang, David Tsai, Allen Yeung, 768 F.2d 518, 3rd Cir. (1985)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- The CISG in IsraelDocument24 pagesThe CISG in IsraelDimaNo ratings yet

- Mpaa MotDocument11 pagesMpaa MottorrentfreakNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals Second Circuit.: No. 557. No. 558. Docket 32404. Docket 32405Document12 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Second Circuit.: No. 557. No. 558. Docket 32404. Docket 32405Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Choice of Law in TortDocument39 pagesChoice of Law in TortMaryam ShamteNo ratings yet

- Motion of Kyle Goodwin To Unseal Search Warrant Materials & Brief in Support IDocument14 pagesMotion of Kyle Goodwin To Unseal Search Warrant Materials & Brief in Support ITorrentFreak_No ratings yet

- Case 3 - Final-1Document18 pagesCase 3 - Final-1Haktan DemirNo ratings yet

- CISG Survey Highlights Issues on Attorneys' Fees, Bankruptcy, ContractsDocument12 pagesCISG Survey Highlights Issues on Attorneys' Fees, Bankruptcy, ContractsNga DinhNo ratings yet

- The Scope of Application of The Right To A Fair Trial in Criminal MattersDocument30 pagesThe Scope of Application of The Right To A Fair Trial in Criminal MattersOrland Marc LuminariasNo ratings yet

- Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum Co.Document9 pagesKiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum Co.Kim BalantaNo ratings yet

- Chiquita Plaintiffs Reply To Motion For ReconsiderationDocument8 pagesChiquita Plaintiffs Reply To Motion For ReconsiderationPaulWolfNo ratings yet

- SideBAR - Published by The Federal Litigation Section of The Federal Bar Association - Spring 2012Document20 pagesSideBAR - Published by The Federal Litigation Section of The Federal Bar Association - Spring 2012Robert E. KohnNo ratings yet

- Google LetterDocument3 pagesGoogle LetteronthecoversongsNo ratings yet

- Case Closed!: New Law Journal 160 NLJ 939 2 July 2010Document4 pagesCase Closed!: New Law Journal 160 NLJ 939 2 July 2010Reena GrewalNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument20 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 2011 Annals Fac LBelgrade IntDocument20 pages2011 Annals Fac LBelgrade IntMinhh ĐứccNo ratings yet

- The Supreme Court Wreaks Havoc in The Lower Federal Courts - TwomblyDocument4 pagesThe Supreme Court Wreaks Havoc in The Lower Federal Courts - TwomblyUmesh HeendeniyaNo ratings yet

- United States v. Rosenberg, 195 F.2d 583, 2d Cir. (1952)Document35 pagesUnited States v. Rosenberg, 195 F.2d 583, 2d Cir. (1952)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 4Document2 pages4Esha AmirNo ratings yet

- The CLOUD Act, E-Evidence, and Individual RightsDocument9 pagesThe CLOUD Act, E-Evidence, and Individual Rightslili.moliNo ratings yet

- Rogerson - Choice of Law in Tort A Missed OpportunityDocument10 pagesRogerson - Choice of Law in Tort A Missed OpportunitySwati PandaNo ratings yet

- Criminal Court Remedies InvestigationDocument28 pagesCriminal Court Remedies InvestigationhNo ratings yet

- 13 14 DigestDocument3 pages13 14 DigestDavid_0752No ratings yet

- Renvoi PDFDocument19 pagesRenvoi PDFAazamNo ratings yet

- English Law Jurisdiction CourtsDocument22 pagesEnglish Law Jurisdiction CourtsAnubhutiVarmaNo ratings yet

- Modern Law Review, Wiley The Modern Law ReviewDocument5 pagesModern Law Review, Wiley The Modern Law ReviewGantulga EnkhgaramgaiNo ratings yet

- Order Denying Rule 50 MotionsDocument20 pagesOrder Denying Rule 50 MotionsulmontNo ratings yet

- A Second Look at ArbitrabilityDocument37 pagesA Second Look at ArbitrabilitylulakrynskiNo ratings yet

- Forrest Denial of Defense Motion in Silk Road CaseDocument51 pagesForrest Denial of Defense Motion in Silk Road CaseAndy GreenbergNo ratings yet

- Heidelberg Americas v. Tokyo Kikai, 333 F.3d 38, 1st Cir. (2003)Document5 pagesHeidelberg Americas v. Tokyo Kikai, 333 F.3d 38, 1st Cir. (2003)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Cyber Law Project: D - R M L N L U - L, U PDocument21 pagesCyber Law Project: D - R M L N L U - L, U PRishi SehgalNo ratings yet

- Small v. United StatesDocument2 pagesSmall v. United StatesAndrew M. AcederaNo ratings yet

- The Hours Are Long - Unreasonable Delay After JordanDocument21 pagesThe Hours Are Long - Unreasonable Delay After JordanjzaprudkmkvxcryqtvNo ratings yet

- Thesis 1st DraftDocument40 pagesThesis 1st DraftKumsisa DejeneNo ratings yet

- Giorgi Glob. Holdings v. SmulskiDocument3 pagesGiorgi Glob. Holdings v. SmulskiJay TabuzoNo ratings yet

- Part I: International Commercial Arbitration, Chapter 6: Pathological Arbitration Clauses: Another Lawyers' Nightmare Comes TrueDocument9 pagesPart I: International Commercial Arbitration, Chapter 6: Pathological Arbitration Clauses: Another Lawyers' Nightmare Comes TruelauwenjinNo ratings yet

- United States v. Joseph Rodia, 194 F.3d 465, 3rd Cir. (1999)Document24 pagesUnited States v. Joseph Rodia, 194 F.3d 465, 3rd Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Yarn Industries, Inc. v. Krupp International, Inc., 736 F.2d 125, 4th Cir. (1984)Document6 pagesYarn Industries, Inc. v. Krupp International, Inc., 736 F.2d 125, 4th Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- ElcomSoft v. Passcovery Et. Al.Document14 pagesElcomSoft v. Passcovery Et. Al.Patent LitigationNo ratings yet

- CH - 4 JurisDocument6 pagesCH - 4 JurisM Ümer ToorNo ratings yet

- 0000013819Document5 pages0000013819Iyeke XcayalaNo ratings yet

- Board of Trade Vs OwenDocument111 pagesBoard of Trade Vs OwenTushabe PeterNo ratings yet

- State Immunity and Diplomatic Immunity Against Civil SuitDocument5 pagesState Immunity and Diplomatic Immunity Against Civil SuitFahmi PrayogaNo ratings yet

- Prenda Porn Extortion Racketeering Referred To IRSDocument11 pagesPrenda Porn Extortion Racketeering Referred To IRSmary engNo ratings yet

- Alexis Ac Robocop Et Al V The State Alexis Ac Robocop Et AlDocument8 pagesAlexis Ac Robocop Et Al V The State Alexis Ac Robocop Et AlrochardharricharanNo ratings yet

- Guevarra Vs AlmodovarDocument12 pagesGuevarra Vs AlmodovarelobeniaNo ratings yet

- United States v. DiRico, 69 F.3d 531, 1st Cir. (1995)Document7 pagesUnited States v. DiRico, 69 F.3d 531, 1st Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Lessons from Recent Obscenity ProsecutionsDocument10 pagesLessons from Recent Obscenity ProsecutionsColigny1977No ratings yet

- Jurisdiction Over The CaseDocument33 pagesJurisdiction Over The CaseAna leah Orbeta-mamburam100% (1)

- Stavrula KarapapaDocument20 pagesStavrula Karapapavishwas123No ratings yet

- Admissibility of Digital Evidence in BangladeshDocument5 pagesAdmissibility of Digital Evidence in BangladeshTanbir NahianNo ratings yet

- 26 - Order For Default JudgmentDocument13 pages26 - Order For Default JudgmentCynthia Stine100% (2)

- New Zealand Deportation Cases & The International Conventions: 2023, #1From EverandNew Zealand Deportation Cases & The International Conventions: 2023, #1No ratings yet

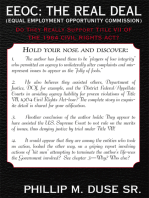

- Eeoc: the Real Deal: (Equal Employment Opportunity Commission)From EverandEeoc: the Real Deal: (Equal Employment Opportunity Commission)No ratings yet

- Eo Chinese Mil CosDocument4 pagesEo Chinese Mil CosMichael RandolphNo ratings yet

- HFS US New 08-01-2020 PDFDocument22 pagesHFS US New 08-01-2020 PDFMichael RandolphNo ratings yet

- How To Make Market Competition Work in Healthcare: Kerianne H. Holman, MD, and Rodney A. Hayward, MDDocument5 pagesHow To Make Market Competition Work in Healthcare: Kerianne H. Holman, MD, and Rodney A. Hayward, MDMichael RandolphNo ratings yet

- The Information and Consultation Agreement: Entered Into by TheDocument16 pagesThe Information and Consultation Agreement: Entered Into by TheMichael RandolphNo ratings yet

- VIMA - Model Shareholders AgreementDocument51 pagesVIMA - Model Shareholders AgreementMichael RandolphNo ratings yet

- VIMA - Model Non-Disclosure AgreementDocument13 pagesVIMA - Model Non-Disclosure AgreementMichael RandolphNo ratings yet

- Vima - CareDocument17 pagesVima - CareMichael RandolphNo ratings yet

- VIMA - Model Long Form Term SheetDocument24 pagesVIMA - Model Long Form Term SheetMichael Randolph100% (1)

- The New Crowdfunding Registration Exemption - Good Idea Bad ExecuDocument15 pagesThe New Crowdfunding Registration Exemption - Good Idea Bad ExecuMichael RandolphNo ratings yet

- The Very Faithless Elector PDFDocument21 pagesThe Very Faithless Elector PDFMichael RandolphNo ratings yet

- VIMA - Model Subscription AgreementDocument52 pagesVIMA - Model Subscription AgreementMichael RandolphNo ratings yet

- VIMA - Model Short Form Term SheetDocument13 pagesVIMA - Model Short Form Term SheetMichael RandolphNo ratings yet

- Adyen ProspectusDocument367 pagesAdyen ProspectusMichael RandolphNo ratings yet

- Wynn.v.AP PDFDocument31 pagesWynn.v.AP PDFMichael RandolphNo ratings yet

- Prima Facie DefinitionDocument1 pagePrima Facie DefinitionMichael RandolphNo ratings yet

- Guide To Interpleading Earnest Money DepositsDocument25 pagesGuide To Interpleading Earnest Money DepositsMichael RandolphNo ratings yet

- UMB Business Launch Competition ApplicationDocument3 pagesUMB Business Launch Competition ApplicationMichael RandolphNo ratings yet

- 8.15 CEO Employment Agreement Pro EmployerDocument9 pages8.15 CEO Employment Agreement Pro EmployerMichael RandolphNo ratings yet

- IBM-ConsultancyStudyReport Eng PDFDocument130 pagesIBM-ConsultancyStudyReport Eng PDFMichael RandolphNo ratings yet

- Buyer FormsDocument24 pagesBuyer FormsMichael RandolphNo ratings yet

- Equifax Homebuyers HandbookDocument23 pagesEquifax Homebuyers HandbookMichael RandolphNo ratings yet

- 2013 Online Club TrainingDocument30 pages2013 Online Club TrainingMichael RandolphNo ratings yet

- 2012 4447 Aleynikov Sergey AppBriefDocument60 pages2012 4447 Aleynikov Sergey AppBrieftom clearyNo ratings yet

- Leaflet THBDocument3 pagesLeaflet THBMichael RandolphNo ratings yet

- TWCDocument1 pageTWCMichael RandolphNo ratings yet

- Business Launch Competition - FINAL APPLICATION: Vdc@umb - EduDocument3 pagesBusiness Launch Competition - FINAL APPLICATION: Vdc@umb - EduMichael RandolphNo ratings yet

- Apollo 8000 Data SheetDocument8 pagesApollo 8000 Data SheetMichael RandolphNo ratings yet

- Aleynikov Motion To Dismiss StateDocument109 pagesAleynikov Motion To Dismiss StateMichael RandolphNo ratings yet

- MCSA - Windows Server 2008Document9 pagesMCSA - Windows Server 2008Michael RandolphNo ratings yet

- Humanitarian Negotiation Manual PDFDocument91 pagesHumanitarian Negotiation Manual PDFΑλεξαντερ ΤερσενιδηςNo ratings yet

- The Kashmir IssueDocument2 pagesThe Kashmir IssueSaadat LarikNo ratings yet

- VL Order Judge Mary Ann Grilli - Santa Clara County Superior Court - Dong v. Garbe Vexatious Litigant Proceeding Santa Clara Superior Court - Attorney Brad Baugh - Presiding Judge Rise Jones PichonDocument6 pagesVL Order Judge Mary Ann Grilli - Santa Clara County Superior Court - Dong v. Garbe Vexatious Litigant Proceeding Santa Clara Superior Court - Attorney Brad Baugh - Presiding Judge Rise Jones PichonCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasNo ratings yet

- Other Social Welfare Policies and ProgramsDocument7 pagesOther Social Welfare Policies and ProgramsJimron Brix AlcalaNo ratings yet

- Central Mindanao University v. RepublicDocument2 pagesCentral Mindanao University v. RepublicJardine Precious MiroyNo ratings yet

- Klan in MaineDocument8 pagesKlan in MaineNate McFadden100% (1)

- Karnataka Land (Restriction On Transfer) Act, 1991Document7 pagesKarnataka Land (Restriction On Transfer) Act, 1991Latest Laws TeamNo ratings yet

- A Kind of Coup - by Ronald Dworkin - The New York Review of BooksDocument3 pagesA Kind of Coup - by Ronald Dworkin - The New York Review of BooksDada BabelNo ratings yet

- Philippine Statutory ConstructionDocument6 pagesPhilippine Statutory Constructionben carlo ramos srNo ratings yet

- Critical - Review - Jindal Stainless Ltd. & Anr. v. State of Haryana & OrsDocument5 pagesCritical - Review - Jindal Stainless Ltd. & Anr. v. State of Haryana & OrsSubh AshishNo ratings yet

- Limkaichong v. LBP PDFDocument70 pagesLimkaichong v. LBP PDFChap ChoyNo ratings yet

- Summaries of Writ of Amparo, Habeas data, and KalikasanDocument15 pagesSummaries of Writ of Amparo, Habeas data, and KalikasanPhillip Joshua GonzalesNo ratings yet

- HG Module 3Document3 pagesHG Module 3Emmanuel M. Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Foundations of American Democracy (GoPo Unit 1)Document170 pagesFoundations of American Democracy (GoPo Unit 1)Yuvika ShendgeNo ratings yet

- Philippine Journalist Vs Journal EMPLOYEES UNION (G.R. NO. 192601 JUNE 3, 2013)Document1 pagePhilippine Journalist Vs Journal EMPLOYEES UNION (G.R. NO. 192601 JUNE 3, 2013)RobertNo ratings yet

- Guide Certificate636017830879050722 PDFDocument35 pagesGuide Certificate636017830879050722 PDFAll Open EverythingNo ratings yet

- Corporate Governance: Governance, Business Ethics, Risk Management, and Internal ControlDocument26 pagesCorporate Governance: Governance, Business Ethics, Risk Management, and Internal ControlPipz G. CastroNo ratings yet

- Office of Profit: A Constitutional Disqualification for LegislatorsDocument17 pagesOffice of Profit: A Constitutional Disqualification for Legislatorssiddharth0603No ratings yet

- PEOPLE VS. bERNARDINO gAFFUDDocument3 pagesPEOPLE VS. bERNARDINO gAFFUDmakNo ratings yet

- UNITED STATES Vs ExaltacionDocument3 pagesUNITED STATES Vs Exaltacionautumn moonNo ratings yet

- 81Document2 pages81Trem GallenteNo ratings yet

- Political Economy of Mass MediaDocument17 pagesPolitical Economy of Mass MediaMusa RashidNo ratings yet

- Che Guevara's Racism, Misogyny and Lack of Ethics ExposedDocument14 pagesChe Guevara's Racism, Misogyny and Lack of Ethics Exposedtamakun0No ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument8 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- PMU Letter - Regading Construction Work - Uyanga TranslationDocument2 pagesPMU Letter - Regading Construction Work - Uyanga TranslationУянга ВеганNo ratings yet

- CORAZON KO v. VIRGINIA DY ARAMBURO GR No. 190995, Aug 09, 2017 Co-Ownership, Sale, Void vs. Voidable Sale, Prescription - PINAY JURISTDocument6 pagesCORAZON KO v. VIRGINIA DY ARAMBURO GR No. 190995, Aug 09, 2017 Co-Ownership, Sale, Void vs. Voidable Sale, Prescription - PINAY JURISTDJ MikeNo ratings yet

- Lawyer Disbarment GroundsDocument31 pagesLawyer Disbarment GroundsJo RylNo ratings yet

- 4) GR 201043, Republic vs. YahonDocument8 pages4) GR 201043, Republic vs. YahonLeopoldo, Jr. BlancoNo ratings yet

- FROM MARX TO GRAMSCI AND BACK AGAINDocument16 pagesFROM MARX TO GRAMSCI AND BACK AGAINzepapiNo ratings yet