Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Eastern Broadcasting Corp. v. Dans, Jr.

Uploaded by

Noreenesse SantosCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Eastern Broadcasting Corp. v. Dans, Jr.

Uploaded by

Noreenesse SantosCopyright:

Available Formats

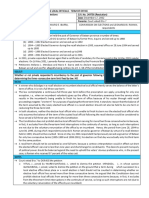

G.R. No.

L-59329

Eastern Broadcasting Corp. v. Dans, Jr.

July 19, 1985

Gutierrez, Jr., J.

FACTS:

Radio Station DYRE was closed on the ground that the radio station was used to incite people to sedition.

A petition was filed by Eastern Broadcasting to compel the Minister of Transportation and

Communications, Ceferino S. Carreon (Commissioner, National Telecommunications Commission), et. al.

to allow the reopening of Radio Station DYRE which had been summarily closed on grounds of national

security; alleging denial of due process and violation of its right of freedom of speech.

On 25 March 1985, before the Court could promulgate a decision squarely passing upon all the issues

raised, Eastern Broadcasting through its president, Mr. Rene G. Espina suddenly filed a motion to withdraw

or dismiss the petition. Eastern Broadcasting alleged that (1) it has already sold its radio broadcasting station

in favor of Manuel B. Pastrana as well as its rights and interest in the radio station DYRE in Cebu including

its right to operate and its equipment; (2) the National Telecommunications Commission has expressed its

willingness to grant to the said new owner Manuel B. Pastrana the requisite license and franchise to operate

the said radio station and to approve the sale of the radio transmitter of said station DYRE; (3) in view of

the foregoing, Eastern Broadcasting has no longer any interest in said case, and the new owner, Manuel B.

Pastrana is likewise not interested in pursuing the case any further.

ISSUE(s):

Whether or not radio broadcasting enjoys a more limited form. YES

HELD:

The case has become moot and academic. However, for the guidance of inferior courts and administrative

tribunals exercising quasi-judicial functions, the Court issues the following guidelines:

(1) The cardinal primary requirements in administrative proceedings laid down by the Court in Ang Tibay

v. Court of Industrial Relations (69 Phil. 635) should be followed before a broadcast station may be

closed or its operations curtailed;

(2) It is necessary to reiterate that while there is no controlling and precise definition of due process, it

furnishes an unavoidable standard to which government action must conform in order that any

deprivation of life, liberty, or property, in each appropriate case, may be valid (Ermita-Malate Hotel

and Motel Operators Association v. City Mayor, 20 SCRA 849);

(3) All forms of media, whether print or broadcast, are entitled to the broad protection of the freedom of

speech and expression clause. The test for limitations on freedom of expression continues to be the

clear and present danger rule - that words are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as

to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that the lawmaker

has a right to prevent;

(4) The clear and present danger test, however, does not lend itself to a simplistic and all embracing

interpretation applicable to all utterances in all forums. Broadcasting has to be licensed. Airwave

frequencies have to be allocated among qualified users;

(5) The clear and present danger test must take the particular circumstances of broadcast media into

account. The supervision of radio stations whether by government or through self-regulation by

the industry itself calls for thoughtful, intelligent and sophisticated handling;

(6) The freedom to comment on public affairs is essential to the vitality of a representative democracy;

and

G.R. No. L-59329

Eastern Broadcasting Corp. v. Dans, Jr.

July 19, 1985

(7) Broadcast stations deserve the special protection given to all forms of media by the due process and

freedom of expression clauses of the Constitution.

A broadcast corporation cannot simply appropriate a certain frequency without regard for government

regulation or for the rights of others. All forms of communication are entitled to the broad protection of

the freedom of expression clause. Necessarily, however, the freedom of television and radio broadcasting

is somewhat lesser in scope than the freedom accorded to newspaper and print media.

Radio broadcasting, more than other forms of communications, receives the most limited protection from

the free expression clause, because:

o First, broadcast media have established a uniquely pervasive presence in the lives of all citizens. Material

presented over the airwaves confronts the citizen, not only in public, but in the privacy of his home.

o Second, broadcasting is uniquely accessible to children. Bookstores and motion picture theaters may

be prohibited from making certain material available to children, but the same selectivity cannot be

done in radio or television, where the listener or viewer is constantly tuning in and out. Similar

considerations apply in the area of national security.

The broadcast media have also established a uniquely pervasive presence in the lives of all Filipinos.

Newspapers and current books are found only in metropolitan areas and in the poblaciones of

municipalities accessible to fast and regular transportation. Even here, there are low income masses who

find the cost of books, newspapers, and magazines beyond their humble means. Basic needs like food and

shelter perforce enjoy high priorities. On the other hand, the transistor radio is found everywhere. The

television set is also becoming universal. Their message may be simultaneously received by a national or

regional audience of listeners including the indifferent or unwilling who happen to be within reach of a

blaring radio or television set. The materials broadcast over the airwaves reach every person of every age,

persons of varying susceptibilities to persuasion, persons of different I.Q.s and mental capabilities, persons

whose reactions to inflammatory or offensive speech would be difficult to monitor or predict. The impact

of the vibrant speech is forceful and immediate. Unlike readers of the printed work, the radio audience has

lesser opportunity to cogitate, analyze, and reject the utterance.

Still, the government has a right to be protected against broadcasts which incite the listeners to violently

overthrow it. Radio and television may not be used to organize a rebellion or to signal the start of

widespread uprising. At the same time, the people have a right to be informed. Radio and television would

have little reason for existence if broadcasts are limited to bland, obsequious, or pleasantly entertaining

utterances. Since they are the most convenient and popular means of disseminating varying views on public

issues, they also deserve special protection.

DOCTRINE(s)/KEY POINT(s):

- All forms of communication are entitled to the broad protection of the freedom of expression clause.

Necessarily, however, the freedom of television and radio broadcasting is somewhat lesser in scope than

the freedom accorded to newspaper and print media.

- Radio broadcasting, more than other forms of communications, receives the most limited protection from

the free expression clause, because:

o First, broadcast media have established a uniquely pervasive presence in the lives of all citizens. Material

presented over the airwaves confronts the citizen, not only in public, but in the privacy of his home.

o Second, broadcasting is uniquely accessible to children. Bookstores and motion picture theaters may

be prohibited from making certain material available to children, but the same selectivity cannot be

done in radio or television, where the listener or viewer is constantly tuning in and out. Similar

considerations apply in the area of national security.

You might also like

- Eastern Broadcasting vs. Dans DIGESTDocument1 pageEastern Broadcasting vs. Dans DIGESTJanlo FevidalNo ratings yet

- 3.) People vs. FortesDocument3 pages3.) People vs. FortesFelix DiazNo ratings yet

- Cabansag vs. Fernandez Freedom of Expression and The Administration of JusticeDocument4 pagesCabansag vs. Fernandez Freedom of Expression and The Administration of JusticeRowardNo ratings yet

- Ayer Productions Pty. Ltd. v. CapulongDocument4 pagesAyer Productions Pty. Ltd. v. CapulongNoreenesse Santos100% (1)

- Dela Cruz V People - Case DigestDocument2 pagesDela Cruz V People - Case DigestAbigail TolabingNo ratings yet

- Iglesia Ni Cristo vs. Court of AppealsDocument2 pagesIglesia Ni Cristo vs. Court of AppealsNori100% (1)

- Guanzon v. de Villa, 181 SCRA 623Document14 pagesGuanzon v. de Villa, 181 SCRA 623Christia Sandee SuanNo ratings yet

- Case Digest: Valmonte Vs BelmonteDocument4 pagesCase Digest: Valmonte Vs BelmonteKIM COLLEEN MIRABUENANo ratings yet

- Newsounds vs. DyDocument2 pagesNewsounds vs. DyNina Castillo50% (2)

- People vs. CayatDocument2 pagesPeople vs. Cayatabethzkyyyy100% (1)

- Lagunzad Vs Soto Vda. de GonzalesDocument2 pagesLagunzad Vs Soto Vda. de GonzalesGladys Bantilan100% (1)

- Al-Ghoul vs. CA (Digest)Document2 pagesAl-Ghoul vs. CA (Digest)Eumir Songcuya100% (1)

- 122-ATIENZA - People vs. Fortes (G.R. No. 90643, June 25, 1993)Document2 pages122-ATIENZA - People vs. Fortes (G.R. No. 90643, June 25, 1993)Adrian Gabriel S. Atienza100% (1)

- 34.1 Ortigas & Co. vs. Feati Bank DigestDocument2 pages34.1 Ortigas & Co. vs. Feati Bank DigestEstel Tabumfama100% (4)

- Adiong Vs Comelec Case DigestDocument2 pagesAdiong Vs Comelec Case DigestEbbe Dy100% (1)

- 16 Manila Electric Co Vs LimDocument1 page16 Manila Electric Co Vs Limjed_sindaNo ratings yet

- Rights During Trial QaDocument7 pagesRights During Trial Qaadonis.orillaNo ratings yet

- MIRASOL V DPWHDocument1 pageMIRASOL V DPWHLei Jeus TaligatosNo ratings yet

- Case Digest of Ayer Productions Vs CapulongDocument2 pagesCase Digest of Ayer Productions Vs CapulongMarco Rvs86% (7)

- Freedman v. Maryland DigestDocument2 pagesFreedman v. Maryland DigestTrisha Dela RosaNo ratings yet

- Lagunzad Vs Sotto Vda GonzalesDocument3 pagesLagunzad Vs Sotto Vda GonzalesJessamine OrioqueNo ratings yet

- Near V. Minnesota: Constitutional Law IiDocument15 pagesNear V. Minnesota: Constitutional Law IiBelle CabalNo ratings yet

- Adiong v. ComelecDocument2 pagesAdiong v. ComelecSean GalvezNo ratings yet

- Sanidad VS ComelecDocument2 pagesSanidad VS ComelecRuss Tuazon100% (1)

- Lopez vs. Court of Appeals (GR L-26549, 31 July 1970) : FactsDocument6 pagesLopez vs. Court of Appeals (GR L-26549, 31 July 1970) : FactsAlicia Dangeline RañolaNo ratings yet

- Soriano vs. LaguardiaDocument2 pagesSoriano vs. LaguardiaVanityHughNo ratings yet

- PP V DueroDocument2 pagesPP V DueroCarlyn Belle de Guzman50% (2)

- Rotary International v. Rotary Club of DuarteDocument2 pagesRotary International v. Rotary Club of DuarteChou Takahiro100% (1)

- GMA Netwaork v. COMELEC (Digest)Document2 pagesGMA Netwaork v. COMELEC (Digest)Arahbells100% (1)

- Phil Journ Inc VS Thoenen Case DigestDocument4 pagesPhil Journ Inc VS Thoenen Case DigestIlyka Jean Sionzon100% (1)

- IBP Vs Mayor AtienzaDocument3 pagesIBP Vs Mayor AtienzaNath AntonioNo ratings yet

- Lopez vs. Court of Appeals Freedom of Expression, Libel and National SecurityDocument2 pagesLopez vs. Court of Appeals Freedom of Expression, Libel and National SecurityRowardNo ratings yet

- Case # 65 MTRCB V AbscbnDocument2 pagesCase # 65 MTRCB V AbscbnEa GabotNo ratings yet

- VILLAR V TIP CDDocument2 pagesVILLAR V TIP CDheloiseglaoNo ratings yet

- 17 Navarro Vs VillegasDocument1 page17 Navarro Vs VillegasErwin Bernardino100% (1)

- Pita vs. Court of Appeals, 178 SCRA 362, October 05, 1989 Case DigestDocument2 pagesPita vs. Court of Appeals, 178 SCRA 362, October 05, 1989 Case DigestElla Kriziana Cruz67% (3)

- Pineda-Ng Vs PeopleDocument1 pagePineda-Ng Vs PeopleJudy Miraflores DumdumaNo ratings yet

- Ayer Productions VS CapulongDocument2 pagesAyer Productions VS CapulongAlyssa Mae Ogao-ogaoNo ratings yet

- Guanzon vs. Devilla Case DigestDocument2 pagesGuanzon vs. Devilla Case DigestCaitlin KintanarNo ratings yet

- Castro Vs PabalanDocument3 pagesCastro Vs PabalanaldinNo ratings yet

- in Re - Column of Ramon Tulfo 4171990Document8 pagesin Re - Column of Ramon Tulfo 4171990Arahbells100% (1)

- 2008.consti2 Lecture With CasesDocument129 pages2008.consti2 Lecture With CasesJanet Tal-udanNo ratings yet

- Alvero-vs-Dizon (Art 129)Document1 pageAlvero-vs-Dizon (Art 129)tink echivereNo ratings yet

- Corp - Gochan v. YoungDocument2 pagesCorp - Gochan v. YoungIrish GarciaNo ratings yet

- Telecom and Broadcast Attorneys vs. COMELECDocument2 pagesTelecom and Broadcast Attorneys vs. COMELECDana Denisse Ricaplaza100% (1)

- Chavez vs. Secretary Gonzales, G.R. No. 168338 Case DigestDocument3 pagesChavez vs. Secretary Gonzales, G.R. No. 168338 Case DigestElla Kriziana CruzNo ratings yet

- Cantwell v. Connecticut 310 U.S. 296 May 20, 1940Document3 pagesCantwell v. Connecticut 310 U.S. 296 May 20, 1940Edwin VillaNo ratings yet

- Perfecto v. Judge Esidera, A.M. No. RTJ-15-2417, July 22, 2015Document9 pagesPerfecto v. Judge Esidera, A.M. No. RTJ-15-2417, July 22, 2015Matthew Henry RegaladoNo ratings yet

- 42 PEOPLE Vs OTADORADocument2 pages42 PEOPLE Vs OTADORAKeilah ArguellesNo ratings yet

- (Case No. 420) : Prepared By: Cecille Diane DJ. MangaserDocument2 pages(Case No. 420) : Prepared By: Cecille Diane DJ. MangaserCecille MangaserNo ratings yet

- Gonzales V Kalaw KatigbakDocument2 pagesGonzales V Kalaw Katigbakitsmesteph100% (1)

- Del Rosario V de Los SantosDocument2 pagesDel Rosario V de Los SantosMigs GayaresNo ratings yet

- People V ManriquezDocument2 pagesPeople V ManriquezistefifayNo ratings yet

- Malacat V CADocument2 pagesMalacat V CAmmaNo ratings yet

- Pita Vs CADocument2 pagesPita Vs CARandy Sioson100% (2)

- Heirs of Cabais vs. CADocument8 pagesHeirs of Cabais vs. CAAji AmanNo ratings yet

- Adiong Vs Comelec 2Document2 pagesAdiong Vs Comelec 2Raymond PascoNo ratings yet

- Case Digest: Bayan V. Executive Secretary ErmitaDocument3 pagesCase Digest: Bayan V. Executive Secretary ErmitakjsitjarNo ratings yet

- Beltran v. Sec. of Health 476 SCRA 168Document2 pagesBeltran v. Sec. of Health 476 SCRA 168A M I R A100% (1)

- 018 - Eastern Broadcasting V Dans JRDocument4 pages018 - Eastern Broadcasting V Dans JRAubrey AquinoNo ratings yet

- Tan v. Commission On ElectionsDocument3 pagesTan v. Commission On ElectionsNoreenesse SantosNo ratings yet

- The Province of North Cotabato v. The Gov. of The Republic of The Phils. Peace PanelDocument4 pagesThe Province of North Cotabato v. The Gov. of The Republic of The Phils. Peace PanelNoreenesse SantosNo ratings yet

- Why A Federalist Is Now An Anti-Federalist (Edmund S. Tayao)Document2 pagesWhy A Federalist Is Now An Anti-Federalist (Edmund S. Tayao)Noreenesse SantosNo ratings yet

- White Light Corp. v. City of ManilaDocument3 pagesWhite Light Corp. v. City of ManilaNoreenesse SantosNo ratings yet

- Two BBL Strategies (Artemio v. Panganiban)Document2 pagesTwo BBL Strategies (Artemio v. Panganiban)Noreenesse SantosNo ratings yet

- Tano v. SocratesDocument3 pagesTano v. SocratesNoreenesse SantosNo ratings yet

- Sobejana-Condon v. Commission On ElectionsDocument3 pagesSobejana-Condon v. Commission On ElectionsNoreenesse SantosNo ratings yet

- Social Justice Society v. Atienza, Jr.Document5 pagesSocial Justice Society v. Atienza, Jr.Noreenesse Santos100% (1)

- Abueva FederalismDocument19 pagesAbueva FederalismfranzgabrielimperialNo ratings yet

- Socrates v. Commission On ElectionsDocument3 pagesSocrates v. Commission On ElectionsNoreenesse SantosNo ratings yet

- Talaga v. Commission On ElectionsDocument3 pagesTalaga v. Commission On ElectionsNoreenesse SantosNo ratings yet

- Kida v. Senate of The PhilippinesDocument2 pagesKida v. Senate of The PhilippinesNoreenesse SantosNo ratings yet

- Sema v. Commission On ElectionsDocument4 pagesSema v. Commission On ElectionsNoreenesse SantosNo ratings yet

- Samson v. AguirreDocument2 pagesSamson v. AguirreNoreenesse SantosNo ratings yet

- Navarro v. ErmitaDocument4 pagesNavarro v. ErmitaNoreenesse SantosNo ratings yet

- Sangalang v. Intermediate Appellate CourtDocument4 pagesSangalang v. Intermediate Appellate CourtNoreenesse Santos100% (1)

- Samahan NG Mga Progresibong Kabataan v. Quezon City PDFDocument4 pagesSamahan NG Mga Progresibong Kabataan v. Quezon City PDFNoreenesse Santos100% (5)

- Republic v. RambuyongDocument1 pageRepublic v. RambuyongNoreenesse Santos100% (2)

- Judge Dadole v. Commission On AuditDocument2 pagesJudge Dadole v. Commission On AuditNoreenesse SantosNo ratings yet

- Republic v. Court of AppealsDocument3 pagesRepublic v. Court of AppealsNoreenesse SantosNo ratings yet

- Philippine Society For The Prevention of Cruelty To Animals v. Commission On Audit, Et Al.Document2 pagesPhilippine Society For The Prevention of Cruelty To Animals v. Commission On Audit, Et Al.Noreenesse SantosNo ratings yet

- Pimentel v. Aguirre, Et Al.Document2 pagesPimentel v. Aguirre, Et Al.Noreenesse Santos100% (1)

- Philippine Constitutional Framework For Economic Emergency - Expanding The Welfare State, Restricting The National Security (Raul C. Pangalangan)Document16 pagesPhilippine Constitutional Framework For Economic Emergency - Expanding The Welfare State, Restricting The National Security (Raul C. Pangalangan)Noreenesse SantosNo ratings yet

- Rivera III v. Commission On ElectionsDocument1 pageRivera III v. Commission On ElectionsNoreenesse SantosNo ratings yet

- Province of Batangas v. RomuloDocument4 pagesProvince of Batangas v. RomuloNoreenesse Santos100% (1)

- Manila International Airport Authority v. Court of AppealsDocument2 pagesManila International Airport Authority v. Court of AppealsNoreenesse Santos100% (1)

- Ong v. AlegreDocument2 pagesOng v. AlegreNoreenesse SantosNo ratings yet

- Lucena Grand Central Terminal Inc. v. JAC Liner Inc.Document2 pagesLucena Grand Central Terminal Inc. v. JAC Liner Inc.Noreenesse Santos100% (1)

- Disomangcop v. DatumanongDocument3 pagesDisomangcop v. DatumanongNoreenesse SantosNo ratings yet

- Mendoza v. Commission On ElectionsDocument2 pagesMendoza v. Commission On ElectionsNoreenesse SantosNo ratings yet

- Five BoonsDocument1 pageFive BoonsHartford CourantNo ratings yet

- Sigmund Freud TheoryDocument8 pagesSigmund Freud TheoryAnonymous JxRyAPvNo ratings yet

- Remedies For Piracy of DesignsDocument8 pagesRemedies For Piracy of DesignsPriya GargNo ratings yet

- Corporation Law Midterms Practice Questions Until by LawsDocument6 pagesCorporation Law Midterms Practice Questions Until by LawsrubyNo ratings yet

- People Vs ReyesDocument1 pagePeople Vs ReyesOrville CipresNo ratings yet

- Plea BargainingDocument6 pagesPlea BargainingVaishali RathiNo ratings yet

- Top 3 Tips That Will Make Your Goals Come True: Brought To You by Shawn LimDocument8 pagesTop 3 Tips That Will Make Your Goals Come True: Brought To You by Shawn LimGb WongNo ratings yet

- Jayanti Dalal's The Darkness Descends (Jagmohane Shu Jovu?) : A Distress of Blindness and Compromising The SelfDocument5 pagesJayanti Dalal's The Darkness Descends (Jagmohane Shu Jovu?) : A Distress of Blindness and Compromising The SelfAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- The Sixties and The Advent of PostmodernismDocument19 pagesThe Sixties and The Advent of PostmodernismNawresNo ratings yet

- International Law Pressentations1Document11 pagesInternational Law Pressentations1czarinaNo ratings yet

- What Is Social InteractionDocument3 pagesWhat Is Social InteractionAli MirNo ratings yet

- Senate Judiciary Committee - Kavanaugh ReportDocument414 pagesSenate Judiciary Committee - Kavanaugh ReportThe Conservative Treehouse100% (4)

- Sklair, Leslie (1997) - Social Movements For Global Capitalism. The Transnational Capitalist Class in ActionDocument27 pagesSklair, Leslie (1997) - Social Movements For Global Capitalism. The Transnational Capitalist Class in Actionjoaquín arrosamenaNo ratings yet

- SushiDocument2 pagesSushiAiman Aslam KhanNo ratings yet

- Group Assignment - Group 1Document36 pagesGroup Assignment - Group 1tia87No ratings yet

- Discuss The Role of Media in The Politics of Today: Milton Obote Idi AminDocument16 pagesDiscuss The Role of Media in The Politics of Today: Milton Obote Idi AminAdupuk JosephNo ratings yet

- RmsDocument13 pagesRmssyeda hifzaNo ratings yet

- Course Professor Book Author Edition ISBN Pifp Books Tore Onlin eDocument11 pagesCourse Professor Book Author Edition ISBN Pifp Books Tore Onlin ePifp VillanovaNo ratings yet

- Unjust VexationDocument2 pagesUnjust Vexationaiyeeen50% (2)

- Rethinking Ergonomic Chairs: Humanics ErgonomicsDocument3 pagesRethinking Ergonomic Chairs: Humanics ErgonomicsWilliam VenegasNo ratings yet

- General Power of AttorneyDocument2 pagesGeneral Power of Attorneyjoonee09No ratings yet

- Multination Corporate Code of EthicsDocument35 pagesMultination Corporate Code of EthicsRoxana IftimeNo ratings yet

- Koser Lutz 1998Document16 pagesKoser Lutz 1998nini345No ratings yet

- University of Calcutta: Application Form For Under Graduate ExaminationsDocument1 pageUniversity of Calcutta: Application Form For Under Graduate ExaminationsAbhiranjan PalNo ratings yet

- Stages of Group FormationDocument5 pagesStages of Group FormationPrashant Singh JadonNo ratings yet

- Analyzing The Political Rhetorics in The Privilege Speech of Senator Francis "Kiko" Pangilinan On The State of Rice FarmersDocument2 pagesAnalyzing The Political Rhetorics in The Privilege Speech of Senator Francis "Kiko" Pangilinan On The State of Rice FarmersLAWRENCE JOHN BIHAGNo ratings yet

- Academic Writing 2Document19 pagesAcademic Writing 2SelsyyNo ratings yet

- Compediu TesteDocument6 pagesCompediu TesteAlexandra TasmocNo ratings yet

- Why Do People Join Groups: Group Norms: Parallel To Performance and Other Standards Established by The FormalDocument12 pagesWhy Do People Join Groups: Group Norms: Parallel To Performance and Other Standards Established by The FormalNupur PharaskhanewalaNo ratings yet

- Aristotle Concept of CatharsisDocument8 pagesAristotle Concept of CatharsisSohel Bangi75% (4)