Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Albert VS. University Publishing

Uploaded by

Ken AliudinOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Albert VS. University Publishing

Uploaded by

Ken AliudinCopyright:

Available Formats

G.R. No.

L-19118 January 30, 1965

MARIANO A. ALBERT, plaintiff-appellant,

vs.

UNIVERSITY PUBLISHING CO., INC., defendant-appellee.

Uy & Artiaga and Antonio M. Molina for plaintiff-appellant.

Aruego, Mamaril & Associates for defendant-appellees.

(BENGZON, J.P., J.)

Facts:

The University Publishing Co. Inc. through its President Jose Aruego entered into a

contract with Mariano Albert whereby the corporation agreed to pay a certain sum in

installments for the exclusive right to publish his revised commentaries in the RPC and for his

share in the previous sale of the books first edit edition. The corporation failed to pay the

second installment thereby making the whole amount due and demandable (i.e. there was an

acceleration clause). Albert then sued the corporation.

The lower court rendered judgment in favor of Albert and a writ of execution was issued

against the corporation. Albert however, petitioned for a writ of execution against Aruego, as the

real defendant, stating that there is no such entity as University Publishing Co. Inc. Albert

annexed to his petition a certification from the SEC saying that their records contain no such

registered corporation.

The corporation countered by saying that Aruego is not a party to this case and that,

therefore, Alberts petition should be denied. The corporation countered by saying that Aruego is

not a party to this case, and that therefore, Alberts petition should be denied. The

corporation, actually did not want Aruego to be declared a party to the present case is

because there would be no need to institute a separate action against Aruego to be declared

a party to the present case is because there would then be a need to institute a separate

action against Aruego; and if this is done, Aruego can set up the defense of prescription under

the Statute of Limitations.

Held:

1.) The corporation cannot invoke the doctrine of estoppel. The fact of non-registration of

the corporation has not been disputed because the corporation only raised the point that it

and not Aruego is the party defendant thereby assuming that the corporation is an

existing corporation with an independent juridical personality. HOWEVER, precisely on account of

non- registration, it cannot be considered a corporation not even a corporation de facto. It has

therefore no personality separate from Aruego; it cannot be sued independently. The estoppel

doctrine has not been invoked and even if it had been, it is not applicable to the case at bar: (a)

Aruego had represented a non-existing entity and induced not only Albert but also the court

to believe in such representation (b) He signed the contract as president of the

corporation stating that this was a corporation duly organized and existing under the laws of

the Philippines. One who induced another to act upon his willful misrepresentation that a

corporation was duly organized and existing under the law, cannot thereafter set up against

his victim the principle of corporation by estoppel.

2.) Aruego is the real defendant as he had control over the proceedings. Had Aruego been

named as party defendant instead of or together with the corporation, there would be no

room for debate as to his personal liability. Since he was not so named, matters of due process

have arisen. Parties to a suit are persons who have a right to control the proceedings, to

make defense, to adduce and crossexamine witnesses and to appeal from a decision. In the case

at bar, Aruego, was and in reality, the one who answered and litigated through his own firm as

counsel. He was in fact, if not on name, the defendant. Clearly then Aruego had his day in

court as the real defendant and due process of law has been substantially observed.

3.) Aruego is the real party in interest because he reaped the benefits from the contract.

You might also like

- Albert v. University Publishing Co., 13 SCRA 84 (1965)Document5 pagesAlbert v. University Publishing Co., 13 SCRA 84 (1965)inno KalNo ratings yet

- Albert Vs University Publishing CoDocument1 pageAlbert Vs University Publishing CoSyoi DiazxNo ratings yet

- 3 Corpo ThreeeeeeeDocument24 pages3 Corpo ThreeeeeeeMiko TabandaNo ratings yet

- Albert V University Publishing Co - DigestDocument3 pagesAlbert V University Publishing Co - DigestBelle MaturanNo ratings yet

- Salvatierra vs. GarlitosDocument2 pagesSalvatierra vs. GarlitosVanya Klarika NuqueNo ratings yet

- Chiang Kai ShiekDocument2 pagesChiang Kai ShiekRaymart SalamidaNo ratings yet

- 28 - Soriano Vs CA 174 Scra 195Document10 pages28 - Soriano Vs CA 174 Scra 195Anonymous hbUJnBNo ratings yet

- Hall vs. PiccioDocument5 pagesHall vs. Piccio8111 aaa 1118No ratings yet

- Corpo Case DigestDocument6 pagesCorpo Case DigestWresen AnnNo ratings yet

- Prelims Notes (Corpo)Document9 pagesPrelims Notes (Corpo)charmagne cuevasNo ratings yet

- Corporation Law Case Digests - 1 PDFDocument113 pagesCorporation Law Case Digests - 1 PDFMalaica Nina Maloloy-onNo ratings yet

- 16 Lumanlan vs. CuraDocument2 pages16 Lumanlan vs. CuraJpSocratesNo ratings yet

- Soriano VsDocument2 pagesSoriano VsRaymart SalamidaNo ratings yet

- Case Digest From P 43 OnwardsDocument15 pagesCase Digest From P 43 OnwardsDiana DungaoNo ratings yet

- Hall vs. PiccioDocument1 pageHall vs. PiccioNei BacayNo ratings yet

- McConnel V CADocument2 pagesMcConnel V CARaymond Cheng100% (2)

- McConnell V CADocument1 pageMcConnell V CAPB AlyNo ratings yet

- Salvatierra Vs GarlitosDocument2 pagesSalvatierra Vs GarlitosChilzia RojasNo ratings yet

- Francisco Vs GSISDocument10 pagesFrancisco Vs GSISkrys_elleNo ratings yet

- 002 Universal Mills Corp. v. Universal Textile Mills Inc.Document2 pages002 Universal Mills Corp. v. Universal Textile Mills Inc.joyce100% (3)

- 11 Clavecilla Radio System v. Antillon (Garcia)Document1 page11 Clavecilla Radio System v. Antillon (Garcia)ASGarcia24No ratings yet

- Vda de Salvatierra Vs GarlitosDocument1 pageVda de Salvatierra Vs GarlitosJosiah BalgosNo ratings yet

- Palacio V Fely TransportDocument2 pagesPalacio V Fely TransportJued CisnerosNo ratings yet

- Ang Si Heng VDocument1 pageAng Si Heng VLadyfirst MANo ratings yet

- 04.0 Gen Credit Vs Alsons - DigestDocument1 page04.0 Gen Credit Vs Alsons - DigestsarmientoelizabethNo ratings yet

- BPI V de CosterDocument2 pagesBPI V de CosterTonifranz Sareno100% (1)

- Sulo NG Bayan, Inc. vs. Araneta, Inc., 72 SCRA 347Document6 pagesSulo NG Bayan, Inc. vs. Araneta, Inc., 72 SCRA 347Irish Wahid100% (1)

- 155 Ellingwood v. Wolf's Head Oil Refining (Acido)Document2 pages155 Ellingwood v. Wolf's Head Oil Refining (Acido)Jovelan EscañoNo ratings yet

- SP - Fernandez V MaravillaDocument1 pageSP - Fernandez V MaravillaCzar Ian AgbayaniNo ratings yet

- Yu Chuck Vs Kong Li PoDocument1 pageYu Chuck Vs Kong Li PoAliceNo ratings yet

- Philippine Institute of ArbitratorsDocument62 pagesPhilippine Institute of ArbitratorsjessconvocarNo ratings yet

- Tan Boon Bee V Jarencio DigestDocument1 pageTan Boon Bee V Jarencio DigestRejane MarasiganNo ratings yet

- Corpo Cases - RanadaDocument11 pagesCorpo Cases - RanadaJohn Rosendo GalangNo ratings yet

- 12 PASAR vs. LIMDocument2 pages12 PASAR vs. LIMmei atienzaNo ratings yet

- Lim Tong Lim v. Philippine Fishing Gear Industries, Inc., G.R. No. 136448Document14 pagesLim Tong Lim v. Philippine Fishing Gear Industries, Inc., G.R. No. 136448Krister VallenteNo ratings yet

- Del Monte v. Court of AppealsDocument1 pageDel Monte v. Court of Appealsnirvanalitol montoro100% (1)

- Heirs of Pael vs. Ca FactsDocument2 pagesHeirs of Pael vs. Ca FactsDenise DianeNo ratings yet

- Corpo CASE DigestsDocument13 pagesCorpo CASE DigestskkkNo ratings yet

- Universal Mills Corp V Textile MillsDocument1 pageUniversal Mills Corp V Textile MillsMiguel CastricionesNo ratings yet

- Form and Contents DigestedDocument6 pagesForm and Contents DigestedFran JaramillaNo ratings yet

- PADGETT vs. BABCOCKDocument1 pagePADGETT vs. BABCOCKRuth TenajerosNo ratings yet

- Sample Bar Answers AbuelDocument5 pagesSample Bar Answers AbuelMadeleine RomeroNo ratings yet

- What Is Genuine Issue?Document11 pagesWhat Is Genuine Issue?Jay ArNo ratings yet

- 89 - Pascual vs. OrozcoDocument2 pages89 - Pascual vs. Orozcomimiyuki_No ratings yet

- Corpo Ranada CasesDocument41 pagesCorpo Ranada CasesSusan Sabilala MangallenoNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Fe Tan Uy VDocument7 pagesHeirs of Fe Tan Uy VHermosa GreggNo ratings yet

- Pirovana Vs de La RamaDocument2 pagesPirovana Vs de La Ramasexy_lhanz017507No ratings yet

- Asia Banking Corp. vs. Standard Products Co. Inc.Document2 pagesAsia Banking Corp. vs. Standard Products Co. Inc.talla aldoverNo ratings yet

- Corp Digest Week 2Document4 pagesCorp Digest Week 2JessieRealistaNo ratings yet

- Ramon C. Lee and Antonio Lacdao v. The Hon. Court of AppealsDocument1 pageRamon C. Lee and Antonio Lacdao v. The Hon. Court of AppealsTeff QuibodNo ratings yet

- Villa Rey Transit Vs FerrerDocument2 pagesVilla Rey Transit Vs FerrerRia Kriselle Francia Pabale100% (2)

- Chiang Kai Shek School VsDocument2 pagesChiang Kai Shek School VsAmado EspejoNo ratings yet

- ChatGPT Case DigestsDocument8 pagesChatGPT Case DigestsAtheena Marie PalomariaNo ratings yet

- Corpo Case DigestsDocument602 pagesCorpo Case DigestsMhayBinuyaJuanzonNo ratings yet

- 10 Yasuma Vs Heirs of de VillaDocument4 pages10 Yasuma Vs Heirs of de VillaCharm Divina LascotaNo ratings yet

- Universal Mills V Universal Textile Mills DigestDocument1 pageUniversal Mills V Universal Textile Mills DigestRejane MarasiganNo ratings yet

- La Campana Coffee Factory V KaisahanDocument2 pagesLa Campana Coffee Factory V KaisahanJued CisnerosNo ratings yet

- Labor - Digest - Imperial Textile Mills vs. NLRC - UpdatDocument2 pagesLabor - Digest - Imperial Textile Mills vs. NLRC - UpdatEri WatanabeNo ratings yet

- THOM v. BALTIMORE TRUST CO.Document2 pagesTHOM v. BALTIMORE TRUST CO.Karen Selina AquinoNo ratings yet

- Albert v. University Publishing (Jore)Document2 pagesAlbert v. University Publishing (Jore)mjpjoreNo ratings yet

- Waiver and RenunciationDocument1 pageWaiver and RenunciationKen AliudinNo ratings yet

- Tax Law 2019 Bar ExaminationsDocument10 pagesTax Law 2019 Bar ExaminationsKen AliudinNo ratings yet

- Eo 266Document3 pagesEo 266Ken AliudinNo ratings yet

- Petition For Recognition SampleDocument5 pagesPetition For Recognition SampleKen Aliudin100% (1)

- Petition For Recognition of Foreign JudgmentDocument2 pagesPetition For Recognition of Foreign JudgmentKen AliudinNo ratings yet

- Aquino Issues EO 23 On Indefinite Log BanDocument2 pagesAquino Issues EO 23 On Indefinite Log BanKen AliudinNo ratings yet

- People vs. TanDocument1 pagePeople vs. TanKen AliudinNo ratings yet

- Custom Search: The Lawphil Project - Arellano Law FoundationDocument1 pageCustom Search: The Lawphil Project - Arellano Law FoundationKen AliudinNo ratings yet

- Farolan V Cta DigestDocument1 pageFarolan V Cta Digestmark0% (1)

- Aguas v. LlemosDocument2 pagesAguas v. Llemoschappy_leigh118No ratings yet

- Notice: Debarment Notices Schools and Libraries Universal Service Support Mechanism: Bokhari, HaiderDocument3 pagesNotice: Debarment Notices Schools and Libraries Universal Service Support Mechanism: Bokhari, HaiderJustia.comNo ratings yet

- Relinqueshment DeedDocument2 pagesRelinqueshment DeedParul SinghNo ratings yet

- PNB Vs CA & PADILLADocument1 pagePNB Vs CA & PADILLAJoel Milan50% (2)

- 4a - S Q and A To Bar Sales and LeaseDocument30 pages4a - S Q and A To Bar Sales and LeaseJessyyyyy123No ratings yet

- Offer Letter For Residential Accommodation Format of Leased AccomodationDocument3 pagesOffer Letter For Residential Accommodation Format of Leased Accomodationanon_788224026No ratings yet

- Affidavit of Loss TITLEDocument2 pagesAffidavit of Loss TITLEDiazNo ratings yet

- SDFGSDF 23 Q 4 SDFGDSFDocument1 pageSDFGSDF 23 Q 4 SDFGDSFAdventist Hospital DavaoNo ratings yet

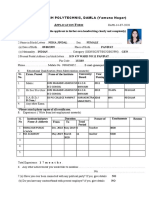

- Seth Jai Parkash Polytechnic, Damla (Yamuna Nagar) : PhotographDocument2 pagesSeth Jai Parkash Polytechnic, Damla (Yamuna Nagar) : PhotographDeepak MittalNo ratings yet

- Paresh Patel v. Diplomat 1419VA Hotels, LLC, 11th Cir. (2015)Document5 pagesParesh Patel v. Diplomat 1419VA Hotels, LLC, 11th Cir. (2015)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Rent RegulationsDocument3 pagesRent RegulationskanyiNo ratings yet

- pp2 Coursework 1 - 201808Document3 pagespp2 Coursework 1 - 201808api-289044570No ratings yet

- PDFDocument2 pagesPDFtyndylsNo ratings yet

- Romualdez Brothers and Harvey and O'Brien For Appellant. Joaquin Ramirez For AppelleesDocument3 pagesRomualdez Brothers and Harvey and O'Brien For Appellant. Joaquin Ramirez For AppelleesCharisa BelistaNo ratings yet

- LA Rocks V Alex & Ani - ComplaintDocument36 pagesLA Rocks V Alex & Ani - ComplaintSarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- Form GST REG-06: Government of IndiaDocument3 pagesForm GST REG-06: Government of IndiaChaitanya DachepallyNo ratings yet

- FL DMV Vehicle Registration ExemptionDocument2 pagesFL DMV Vehicle Registration ExemptionLisa CapriottiNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of Heirship: PhilippinesDocument4 pagesAffidavit of Heirship: PhilippinesMary Jovilyn Mauricio100% (1)

- Affidavit of CommitmentDocument5 pagesAffidavit of Commitmentjimmy_andangNo ratings yet

- AgrarianDocument24 pagesAgrarianGeraldine Gallaron - CasipongNo ratings yet

- Digests Reyes and GuintoDocument4 pagesDigests Reyes and Guintorcciocon08No ratings yet

- Marquez v. EspejoDocument3 pagesMarquez v. EspejoMarie Dudan100% (1)

- Affidavit in Fact Standing CitizenshipDocument4 pagesAffidavit in Fact Standing CitizenshipjoeNo ratings yet

- Francisco Vs Master Iron WorksDocument16 pagesFrancisco Vs Master Iron WorksGuinevere RaymundoNo ratings yet

- Playboy Enterprises, Inc. V. Frena FactsDocument10 pagesPlayboy Enterprises, Inc. V. Frena FactsnvmndNo ratings yet

- Cooperatives - Articles of CooperationDocument1 pageCooperatives - Articles of Cooperationcapamar100% (2)

- Extension of Time ClaimsDocument2 pagesExtension of Time ClaimsindikumaNo ratings yet

- Legal Aspects of Business (LAB) : Post Graduate Programme in Management (PGPM)Document19 pagesLegal Aspects of Business (LAB) : Post Graduate Programme in Management (PGPM)AshiNo ratings yet

- Galindo Vs COA PDFDocument26 pagesGalindo Vs COA PDFAnjNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Negotiable Instruments: As per Indian LawsFrom EverandIntroduction to Negotiable Instruments: As per Indian LawsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- University of Berkshire Hathaway: 30 Years of Lessons Learned from Warren Buffett & Charlie Munger at the Annual Shareholders MeetingFrom EverandUniversity of Berkshire Hathaway: 30 Years of Lessons Learned from Warren Buffett & Charlie Munger at the Annual Shareholders MeetingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (97)

- Buffettology: The Previously Unexplained Techniques That Have Made Warren Buffett American's Most Famous InvestorFrom EverandBuffettology: The Previously Unexplained Techniques That Have Made Warren Buffett American's Most Famous InvestorRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (132)

- AI For Lawyers: How Artificial Intelligence is Adding Value, Amplifying Expertise, and Transforming CareersFrom EverandAI For Lawyers: How Artificial Intelligence is Adding Value, Amplifying Expertise, and Transforming CareersNo ratings yet

- Ben & Jerry's Double-Dip Capitalism: Lead With Your Values and Make Money TooFrom EverandBen & Jerry's Double-Dip Capitalism: Lead With Your Values and Make Money TooRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- The SHRM Essential Guide to Employment Law, Second Edition: A Handbook for HR Professionals, Managers, Businesses, and OrganizationsFrom EverandThe SHRM Essential Guide to Employment Law, Second Edition: A Handbook for HR Professionals, Managers, Businesses, and OrganizationsNo ratings yet

- The Startup Visa: U.S. Immigration Visa Guide for Startups and FoundersFrom EverandThe Startup Visa: U.S. Immigration Visa Guide for Startups and FoundersNo ratings yet

- Wall Street Money Machine: New and Incredible Strategies for Cash Flow and Wealth EnhancementFrom EverandWall Street Money Machine: New and Incredible Strategies for Cash Flow and Wealth EnhancementRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (20)

- Disloyal: A Memoir: The True Story of the Former Personal Attorney to President Donald J. TrumpFrom EverandDisloyal: A Memoir: The True Story of the Former Personal Attorney to President Donald J. TrumpRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (214)

- Getting Through: Cold Calling Techniques To Get Your Foot In The DoorFrom EverandGetting Through: Cold Calling Techniques To Get Your Foot In The DoorRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (63)

- Indian Polity with Indian Constitution & Parliamentary AffairsFrom EverandIndian Polity with Indian Constitution & Parliamentary AffairsNo ratings yet

- The Chickenshit Club: Why the Justice Department Fails to Prosecute ExecutivesWhite Collar CriminalsFrom EverandThe Chickenshit Club: Why the Justice Department Fails to Prosecute ExecutivesWhite Collar CriminalsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (24)

- Contract Law in America: A Social and Economic Case StudyFrom EverandContract Law in America: A Social and Economic Case StudyNo ratings yet

- LLC: LLC Quick start guide - A beginner's guide to Limited liability companies, and starting a businessFrom EverandLLC: LLC Quick start guide - A beginner's guide to Limited liability companies, and starting a businessRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- International Business Law: Cases and MaterialsFrom EverandInternational Business Law: Cases and MaterialsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Venture Deals: Be Smarter Than Your Lawyer and Venture CapitalistFrom EverandVenture Deals: Be Smarter Than Your Lawyer and Venture CapitalistRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (34)

- Nolo's Quick LLC: All You Need to Know About Limited Liability CompaniesFrom EverandNolo's Quick LLC: All You Need to Know About Limited Liability CompaniesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- The Complete Book of Wills, Estates & Trusts (4th Edition): Advice That Can Save You Thousands of Dollars in Legal Fees and TaxesFrom EverandThe Complete Book of Wills, Estates & Trusts (4th Edition): Advice That Can Save You Thousands of Dollars in Legal Fees and TaxesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- How to Win a Merchant Dispute or Fraudulent Chargeback CaseFrom EverandHow to Win a Merchant Dispute or Fraudulent Chargeback CaseNo ratings yet