Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Burma in 2010: A Critical Year in Ethnic Politics

Uploaded by

Pugh JuttaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Burma in 2010: A Critical Year in Ethnic Politics

Uploaded by

Pugh JuttaCopyright:

Available Formats

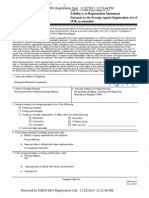

Burma Policy Briefing Nr 1

June 2010

Burma in 2010: A Critical Year in Ethnic Politics

2010 is set to become Burma’s most important

and defining year in two decades. The general CONCLUSIONS & RECOMMENDATIONS

election scheduled by the ruling State Peace

and Development Council (SPDC) could well The 2010 general election could mark

determine the country’s political landscape for the most defining moment in a

another generation. All institutions and parties generation, but new divisions in

are faced with the uncertainties of political Burmese politics are undermining

transformation. This includes the military prospects for democracy and national

SPDC, mass Union Solidarity and Develop- reconciliation

ment Association, opposition National League

for Democracy and diverse ethnic nationality Resolution of Burma’s long-standing

organisations. ethnic crises is integral to the achieve-

ment of real peace, democracy and

At this critical moment in Burma’s history, it constitutional government.

is still not certain whether the general election

will prove an accepted step in the SPDC’s The UN and international community

seven-stage roadmap for political reform or need to establish a common focus on the

become the basis for a new generation of election and its political consequences.

grievances. As the election countdown contin-

ues, new divisions are emerging in Burmese Political and ethnic inclusion is essential

politics, warning that a unique opportunity for if Burma’s long history of state failure is

dialogue and national reconciliation could be to be addressed.

lost.

To establish sustainable ethnic peace,

An inclusive discussion and focus on the elec-

there must be conflict resolution,

tion are vital if its conduct and consequences

humanitarian progress and equitable

are to have common meaning – whether in

participation in the economy, bringing

Burma (Myanmar)1 or the international com-

rights and benefits to all the country’s

munity. Burma’s first election in twenty years

(and third in fifty) marks a rare moment of

peoples and regions.

supposedly national participation in deciding

the representatives of central and local

government. Its historic importance cannot be

Political violence and impasse have long

ignored.

underpinned economic decline and

In no conflict-torn country can a general humanitarian emergency. The problems are

election be expected to resolve all political closely interlinked. But given the primacy of

crises overnight. But it can be an important ethnic conflict in all political eras since

catalyst in establishing peace by acting as an independence, precedent strongly indicates

indicator of popular sentiment and precursor that, unless ethnic peace and justice are

of change. After decades of insurgency and achieved, the legacies of state failure and

military rule, Burma faces many challenges. humanitarian suffering will only continue.

Burma Policy Briefing | 1

BACKGROUND ethnically diverse countries in Asia, minority

peoples make up an estimated third of

Conflict and ethnic grievance have continued Burma’s 56 million, and perceptions of

through every stage of Burma’s political discrimination, poverty and governmental

history since independence in 1948.2 neglect have long fuelled conflict.

Insurgencies broke out among such ethnic

groups as the Karen, Karenni, Mon and Pao Efforts at conflict resolution date back to

during the short-lived parliamentary era independence. Lobbying, however, for ethnic

(1948-62). Armed opposition then reform during the parliamentary era and

accelerated among other nationalities, peace talks with different insurgent groups

including the Kachin, Palaung and Shan, after failed to resolve the many anomalies in the

General Ne Win seized power in a military 1947 constitution, which was federal in style

coup and imposed one-party rule under the but not in name. Subsequently, conflict only

“Burmese Way to Socialism” (1962-88). increased during a quarter century of military

socialist rule under Ne Win’s BSPP.

Burma has since remained in a militarised

state under the present State Peace and The 1974 constitution created for the first

Development Council (formerly State Law time a sense of ethnic equality on the political

and Order Restoration Council: SLORC), map. It demarked seven divisions where most

which assumed power in 1988 after re- of the Burman majority live and seven ethnic

pressing demonstrations that brought down states: Chin, Kachin, Karen, Kayah (Karenni),

the Burma Socialist Programme Party (BSPP) Mon, Rakhine (Arakan) and Shan. But the

government of Ne Win. totalitarian nature of government and

draconian counter-insurgency tactics by the

A ceasefire policy was instituted by the new Burma armed forces (Tatmadaw) in the rural

regime in 1989 and a general election held the countryside only increased antipathy and

following year. But insurgencies have resistance. The national economy collapsed,

continued in several border areas; ceasefire and in 1987 Burma was classified with Least

forces have maintained their arms; and there Developed Country status by the United

is as yet no transition to a democratic system Nations as one of the world’s ten poorest

of government. nations. Change was clearly long overdue.

The social and humanitarian consequences 1988 was a year of seismic events that wit-

have been profound. Burma is one of the nessed mass pro-democracy protests and Ne

poorest countries in Asia and ranks 138 on Win’s resignation but ended with another

the UN Human Development Index, putting security crackdown by a new generation of

it on a par with Cambodia and Pakistan. Tatmadaw leaders. The new regime promised

There are over 180,000 refugees from Burma democratic change, but hopes for swift

in neighbouring countries as well as over two reform soon faded. Only in 2010, more than

million migrant workers, legal and illegal.3 twenty years later, does the SPDC appear

There are an estimated 470,000 people ready to institute a new system of govern-

internally displaced in eastern rural districts.4 ment. This, in turn, is precipitating another

The country remains the world’s largest major upheaval in national politics that is on

producer of illicit opium after Afghanistan.5 a parallel with other tumultuous years of

And treatable or preventable diseases like government change: 1948, 1962 and 1988.

malaria, tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS

continue to take a heavy human toll. For the moment, Burma’s future political

course remains contentious and far from

The whole country is affected by such suf- clear. Will the 2010 election and introduction

fering, but the major impact is felt in ethnic of a new constitution prove the basis for a

nationality regions, especially conflict-zones new era of consensual government or will it

along the borders with Bangladesh, China, perpetuate conflict and national division?

India and Thailand. One of the most The country is entering a critical period.

2 | Burma Policy Briefing

THE CHANGING SOCIO-POLITICAL The most important transformation in politi-

LANDSCAPE cal movements was taking place since inde-

pendence. A major test of wills thus devel-

From 1988 to 1991 Burmese politics under- oped as to who would control Burma’s transi-

went a major transformation that persisted in tion: the Tatmadaw, the NLD or ethnic

most organisational aspects for the next two groups in the borderlands who hoped that the

decades. In 2010, however, the imminence of political pendulum could be swinging their

political change is forcing all groups and way. For the next two decades, there would

parties to reconsider their positions. In be frequent calls in Burma and abroad for

essence, to take part in Burma’s new political “tripartite” dialogue as the most appropriate

system, all parties have to register with the method to resolve the country’s political

authorities and transform. crises.

Under Ne Win’s BSPP government, no ethnic Ultimately, it was the Tatmadaw government

parties were recognised by the constitution. that maintained – and increased – national

Instead, ethnic opposition was represented by control through a combination of measures.

a diversity of militant groups in two major These included the repression of the NLD

blocks: the nine-party National Democratic and other opposition groups, the drawing up

Front (NDF), formed 1976, that sought a fed- of a new constitution by a hand-picked

eral union; and allies of the Communist Party National Convention (1993-2008), and the

of Burma (CPB), which had remained the growth of the pro-military Union Solidarity

country’s largest insurgent force since 1948. and Development Association (USDA,

formed 1993) to over 21 million members. In

This pattern of three-cornered conflict particular, Senior General Than Shwe and the

between the BSPP, NDF and CPB was then Tatmadaw leaders consistently rejected tri-

shattered by the 1988 upheavals that caused partite dialogue and United Nations or other

new groups and alignments to emerge. Four international initiatives seeking to bring

events stood out: Burma’s different parties together around the

same table.

The BSPP was replaced by a new system

of military government under the Ethnic politics thus continued in complex

SLORC-SPDC. and uncertain form. In private, there were

many links between the different ethnic

In 1989 the new government introduced parties and alliances, with a common deter-

an ethnic ceasefire policy following mu- mination to be influential in the country’s

tinies that caused the collapse of the CPB transition. But there was little agreement

and formation of new ethnic forces in about how this should be achieved. Following

northeast Burma. Several ethnic forces, the 1988-91 upheavals, three new and

led by the United Wa State Army importantly different groupings emerged:

(UWSA), quickly agreed to peace terms. electoral, ceasefire and non-ceasefire

The 1990 general election was over- organisations.6

whelmingly won by the National League

On the electoral front, 19 ethnic nationality

for Democracy (NLD) and allied ethnic

parties won seats in the 1990 election, spear-

parties that gained the second largest

headed by the Shan Nationalities League for

block of seats.

Democracy (SNLD). Subsequently, most

Over a dozen MPs-elect went under- parties allied with the NLD through such

ground to escape arrest for having tried initiatives as the 1998 Committee Represent-

to convene a parliament and govern- ing the People’s Parliament. But different

ment. They subsequently joined up with strategies also emerged. From 1995, protest-

other democracy activists, thousands of ing restrictions on freedom of expression, the

whom had fled into NDF-controlled ter- SNLD and allied parties joined the NLD in

ritories in the borderlands since 1988. boycotting the National Convention to draw

Burma Policy Briefing | 3

up the new constitution. But six parties, cating autonomous regions similar to those in

including the Union Pao National China; and a 13-party group led by ex-NDF

Organisation (UPNO), continued to attend. members proposing a federal union. Neither

of these ideas was accepted; SPDC officials

Then in 2002 the SNLD and eight other

equate “federalism” with “disintegration”.8

parties set up the United Nationalities

Ceasefire representatives nevertheless contin-

Alliance (UNA) in an effort to promote the

ued attending the National Convention on

ethnic nationality cause. But like the NLD,

the basis that their demands would go into

the electoral ethnic parties grew increasingly

the historical record and could later be re-

marginalised during the long years of

vived. But ceasefire groups grew increasingly

SLORC-SPDC government.

concerned over the lack of political progress.

Ceasefire politics were similarly diverse. By

Non-ceasefire or insurgent groups also

2000, over 25 ethnic forces, some of which

remained a militant presence. In 1992, a

“united front” highpoint was achieved with

“ The laws are…against the opinions of the the formation of the National Council Union

of Burma (NCUB), bringing together over

twenty anti-government groups. These

international community and the actual desires of the

included the Karen National Union (KNU,

people of Myanmar... formed 1947), long the country’s leading

ethnic force, and National Coalition

All these election laws are based on the unjust and Government Union of Burma (NCGUB,

formed 1990) comprising exile MPs-elect. A

legally unapproved constitution 2008. According to new political dynamic appeared possible,

uniting ethnic militants in the borderlands

these election laws, we feel that the coming elections and democracy activists from the Burman

cannot be free and fair. ” majority in the cities. But differences over

strategy and the growing ceasefire movement

UNA letter to UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, March 2010 eroded the NCUB’s effectiveness.

This was highlighted when the KNU lost its

were small militia or factions, had been headquarters on the Thai border following a

accorded ceasefire status. But 16 major or 1994 breakaway by the Democratic Karen

“official” groups were recognized, including Buddhist Army (DKBA) which accepted a

former NDF members such as the well- ceasefire with the military government. As

organised Kachin Independence Organisa- fighting continued and refugee numbers

tion (KIO, formed 1961) and New Mon State grew, the KNU, NDF, NCUB and other

Party (NMSP, formed 1958). militant groups maintained their advocacy

for ethnic rights. In 2001, an Ethnic

These peace agreements brought the first Nationalities Council (ENC) was also formed

cessation of hostilities and loss of life for to foster broader unity in preparation for

many decades in key border areas, opening tripartite dialogue. But as the SPDC roadmap

up long closed-off regions to development went forward, non-ceasefire strength and

and trade. But political and economic influence declined inside the country.

progress was slow, and resentment grew over

the exploitation of natural resources, such as All the armed ethnic groups also came under

timber and minerals, with limited benefits to pressure to maintain peace in the borderlands

the local people.7 from Asian neighbours, notably China,

Thailand, India and Bangladesh, who

Then at the National Convention, ceasefire accelerated major trade, energy and infra-

representatives put forward their demands in structure projects with the SPDC. The

two different blocks: a 4-party ex-CPB group, economic and humanitarian situation in

the Peace and Democracy Front (PDF), advo- Burma remained grave. But by the 21st

4 | Burma Policy Briefing

century, despite Western boycotts, Burma’s divisions). At the same time, the future

natural resource wealth and strategic position President is required to have military

were gaining Asian priority in one of the experience and 25 percent of seats in the

fastest-developing regions of the world. The legislatures (as well as three key ministries)

idiosyncratic days of Ne Win’s hermetic will be reserved for military appointees.10

“Burmese Way to Socialism” were receding

into history. While the SPDC built a new In one significant change, there will be some

capital at Nay Pyi Taw in the centre of the redrawing of the ethnic map. Seven smaller

country, many of the new natural resource ethnic groups not acknowledged in previous

projects, including gas pipelines and constitutions will gain territories in the form

hydroelectric dams, were located in ethnic of self-administered areas (a “division” for

nationality regions. But it remained the Wa, and “zones” for the Danu, Kokang,

questionable who would really benefit. Lahu, Palaung and Pao in the Shan state and

the Naga in the Sagaing division).

Finally, as the socio-political landscape

changed, ethnic community-based groups This appeared an important historical step.

became more active. Ethnic leaders from But concerns were growing among ethnic

faith-based organisations like the Myanmar parties over the continued military domi-

Council of Churches were go-betweens in nation of government. Not only had there

peace talks, while secular groups increased in been little or no input by electoral and cease-

number from the mid-1990s as the growth of fire groups in the new constitution but there

NGOs gathered pace in the country. Some of were also major uncertainties about how the

these, notably the Shalom Foundation, 2010 election, ceasefire transition and new

concentrated on peace issues, while others system of government would work. SPDC

like the Metta Development Foundation set announcements were rare, intermittent fight-

up aid projects in conflict-affected areas. ing continued with the KNU and other ethnic

forces in the borderlands, and over 2,100

In summary, political change was long political prisoners remained in jail and the

delayed, but community life was by no means NLD leader Aung San Suu Kyi was still under

moribund.9 With the advent of ceasefires, house arrest.11 Detained ethnic leaders in-

international business, the internet and travel cluded Hkun Htun Oo of the electoral SNLD

mobility, Burma in 2010 was different in and General Hso Ten of the ceasefire Shan

many social and economic respects to Ne State Army (North) who had received jail

Win’s one-party state in 1988. terms of 93 and 106 years for alleged sedition.

In the meantime, despite restrictions imposed

THE CHALLENGE OF THE 2010 on other political movements, senior govern-

ELECTION ment officials began canvassing for the USDA

that was expected to turn into a pro-military

The completion of the country’s new consti- party before the polls. As the SPDC’s game

tution during 2008 and announcement of the plan unfolded, opposition groups faced the

2010 election gave a new impetus to political dilemma of how to respond. After two dec-

life. As details emerged, there were few sur- ades of SLORC-SPDC rule, many parties

prises. Burma’s future government will con- hoped that time was still on their side and

tinue to be dominated by the military under that tripartite dialogue, supported by interna-

an executive and unitary system rather than a tional pressure, was still feasible. But two

federal or union system as proposed by pro- government announcements indicated that

democracy and ethnic groups. There will be there was no longer room for complacency.

three elected bodies: a bicameral legislature at In April 2009 the SPDC unilaterally ordered

the national level comprising the People’s that ceasefire groups must transform into

Assembly (lower house) and the National new “Border Guard Force” (BGF) battalions

Assembly (upper house), as well as 14 re- under government authority before the polls.

gional legislatures (for the ethnic states and Then in March 2010, the election laws were

Burma Policy Briefing | 5

announced, setting deadlines for when parties cal repression and “unjust” electoral laws;12

must register to take part – or become and the April resignation of Prime Minister

unregistered and effectively illegal. Thein Sein and 26 other ministers and offi-

cials to form the new Union Solidarity and

Events now began to move fast, with parties Development Party (USDP) from the USDA.

having little choice but to declare themselves The NLD, which for two decades had flown

on or off the SPDC’s political roadmap. the main banner for Burma’s democracy

Hopes for alternative routes to dialogue cause, now faced deregistration and oblivion,

appeared at an end. while continued military domination of gov-

ernment seemed assured via the expected

USDP victory in the election, along with the

“Myanmar is a multinational nation. Peaceful reserved seats for military appointees in the

legislatures.

solution of the problems based on equality and

Against this backdrop, the representation of

solidarity should be the only means when there are ethnic parties began to look very different.

From the outset, there were controversies and

conflicts and contradictions among the national new blurring of the lines between electoral,

ceasefire and non-ceasefire groups as

minorities or between a big race and a smaller race. different parties and citizens decided their

future positions.

They cannot be solved by suppression or resorting to

arms. ” Electoral: A new generation of ethnic elec-

toral parties appeared certain in national

Bao Youxiang, UWSA chairman, November 2009 politics following the polls. Over half the

forty parties registered by the end of May

represented ethnic nationality groups. Some

well-known names left the stage and new

THE ETHNIC RESPONSE actors entered. Given the diversity and small

size of most parties, leaders recognized that

The long-term consequences of the 2010 elec- there was little chance ethnic parties would

tion and government transition may take have much impact on the national stage

years to become clear. In such a strife-torn under existing political conditions. For this

country, new crises can always be expected. reason, the decision whether to stand or not

During 2009-10 the election did not act as a came down to two judgements: to boycott

focus for political and ethnic unity. Instead, because the SPDC roadmap is not regarded as

fresh divisions emerged, reflecting the frag- credible or to stand because, as a popular

mentation that had occurred during previous saying put it, “a constitution is better than no

periods of governmental change. Diverse constitution”.

strategies were discussed, but ultimately most

stakeholder groups were faced with three In particular, after five decades of totalitarian

choices: to participate, boycott or confront rule, some ethnic leaders believed that the

the polls. All were high-risk choices that introduction of a new “power-sharing”

could determine the fate of different political system of multiparty parliamentary govern-

movements for a generation. ment in which 75 percent of seats are

“civilian” offered a better platform for long-

Further shifts in the positions of different po- term change than continued conflict and

litical and ethnic movements can be expected military rule. They argued that such countries

as the election approaches. In particular, the as Indonesia, South Korea and the Philip-

tone of future politics was coloured by two pines had found their own ways for transition

historic decisions early in 2010: the vote of from military rule through parliamentary

the NLD central committee in March not to processes during previous decades. Pro-

stand in the election on the grounds of politi- election leaders were especially keen that

6 | Burma Policy Briefing

ethnic parties stand for constituencies in the tained leaders in order to discuss cooperation

state legislatures which, otherwise, would be in “democratization and national solidar-

won without contest by pro-military and ity”.15 No response was forthcoming, and in

Burman-led parties, notably the USDP. March the UNA sent a statement to UN

Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon calling for

Most ethnic parties still wanted a union syst- international pressure on the SPDC to release

em, and there remained important areas of political prisoners, halt military operations

disagreement, including the powers of the and begin tripartite dialogue with the NLD

ethnic states, cultural rights, security, foreign and ethnic representatives. The 2008 consti-

affairs, and control over natural resources. tution and election laws, the UNA said, were

But it was hoped that reforms could be against “the actual desires of the people”.16

introduced in future legislation, despite the

likely difficulties in moving constitutional The UNA’s decision not to take part was not

amendments. the complete end of the arguments. As hap-

pened with the NLD boycott, some former

Based upon such considerations, the electoral

members tried to support electoral move-

landscape began to change during 2010. Only

ments in new guises. For example, a break-

four of the ethnic parties from the 1990

away group set up a new All Mon Region

general election re-registered (for example,

Democracy Party after a Mon Working Com-

the Union Kayin [Karen] League). They were

mittee, including Mon electoral and ceasefire

joined by a new generation of nationality

representatives, decided not to contest the

parties, reflecting the complexity of ethnic

polls. The Shan Nationals Democratic Party

politics. The Pao National Organisation, for

also included former SNLD members. But as

example, was an amalgamation of the

the election drew closer, there were no

ceasefire group of that name and the UPNO.

guarantees that these new parties would enjoy

The Kachin State Progressive Party (KSPP)

a more durable future than the UNA parties

was formed by Dr Tu Ja and officials of the

now departing the electoral stage.

ceasefire KIO who resigned to help set up a

civilian party. Among the leaders of the Kayin Ceasefire: During 2009-10, similar

People’s Party were a KNU peace mediator uncertainties beset the country’s diverse

Dr Simon Tha and retired naval commander ceasefire groups. In terms of history,

Tun Aung Myint. The Union Democracy membership, finance and territorial control,

the ceasefire forces far outweighed electoral

Party was a broader grouping, set up by vet- parties in their ability to operate

eran Shan politician Shwe Ohn to support the independently and, with an estimated 40,000

ethnic cause in parliament.13 Other ethnic troops under arms, their existence was a

parties included Chin, Kokang, Lahu, Mon, continued reminder of the need for conflict

Mro, Palaung, Rakhine, Shan and Wa identi- resolution in Burma’s “neither war nor

ties. Their common refrain was the pledge to peace” impasse.17

pursue ethnic political and cultural rights in

the establishment of peace and democracy. The ceasefire groups, however, were not

closely allied, consisting of former NDF

In contrast, there were other influential eth- parties, ex-CPB members of the PDF and

nic movements that decided not to contest various small militia or breakaway factions.

the polls. The United Nationalities Alliance of Their ceasefire terms had generally allowed

parties from the 1990 election supported the them to maintain their arms and territory

Shwegondaing Declaration of its NLD ally, until the introduction of a new constitution.

stating that the party could only participate In the meantime, while attending the

on three conditions: the release of political National Convention, they had concentrated

prisoners, constitutional amendments and on building peace through business and

international monitoring of the polls.14 SNLD development programmes. But there were no

members also petitioned the SPDC for a clear agreements on political timetables or

meeting with Hkun Htun Oo and other de- military transition when the new constitution

Burma Policy Briefing | 7

was introduced. Instead, given their broader warned that the people were feeling

social and community structures, ceasefire “threatened and insecure” by government

leaders wanted to support new ethnic parties actions.20 The KIO also went ahead with

in the promised multi-party election and then support for the new KSPP in the elections.

negotiate military change with the new But by May, no major breakthrough had

government following the polls. occurred, with SPDC officials warning the

Disappointed by the 2008 constitution, they NMSP that, if the ceasefire forces did not

wanted to see clear evidence of political transform into BGFs, the situation would

reform before agreeing to transformation. return to “pre-ceasefire” conditions.21

In private, none of the different sides wanted

a return to full-scale conflict. Agreement was

“Every ethnic group wants peace and development still possible if the ceasefire groups were

allowed to transform on compromise terms

for their state. They do not want conflict. They will after the polls. But military training and

deployments were stepped up by different

respond according to how they are treated. ” forces in both China and Thailand border

areas, and local civilians prepared to leave

Gen. Htay Maung, KNU/KNLA Peace Council chairman, April 2010 their homes if fighting should break out.

Meanwhile one ceasefire group, the Shan

State Army (North), split in April over the

BGF issue, and there were rumours that

dissatisfaction was rising among troops in

The SPDC, however, took ceasefire groups by such ceasefire groups as the DKBA that had

surprise with its April 2009 order that the already accepted the BGF system. After over

groups break down into BGF battalions, two decades of ceasefires, no clear or

effectively under government authority. inclusive resolution appeared imminent.

Officers over 50 should retire, and 30

Tatmadaw soldiers would join each 326- Non-ceasefire: As political developments

troop battalion, including one of the three accelerated, non-ceasefire groups became

commanding officers. Most of the smaller further marginalised from national influence

groups acceded; in the ethnic conflict-zones, during 2010. Over a dozen armed ethnic

the Tatmadaw has long supported local groups and factions still exist around Burma’s

militia. But veteran nationalists from such borders. They are allied with Burman

movements as the KIO, NMSP and UWSA dissidents in such fronts as the NCUB, which

refused. Unease then worsened in August includes remnants of the armed All Burma

when the SPDC sent in troops against the Students Democratic Front as well as exile

ceasefire Myanmar National Democratic MPs in the NCGUB. But the strength of non-

Alliance Army in the Kokang region to ceasefire groups has been on the decline since

support a breakaway faction that accepted the the mid-1990s, only four movements still

BGF orders. As many as 200 people were maintaining forces of significant size: the

killed or wounded, and 37,000 refugees fled Chin National Front on the India border, and

into China.18 the KNU, Karenni National Progressive Party

and Shan State Army-South (SSA-S) on the

Talks then continued into 2010 and SPDC Thai border.

deadlines were repeatedly pushed back. The

UWSA chairman Bao Youxiang told the All non-ceasefire groups denounced the 2010

SPDC negotiator Lieutenant General Ye polls. At its February 2010 central committee

Myint that a “peaceful solution” based on meeting, the KNU pledged to “vigorously

“equality and solidarity” should be the only oppose” the election, denouncing it as an

means to resolve conflict.19 His remarks were “extension” of the 2008 constitution “adopted

echoed by General Htay Maung, chairman of through fraud and coercion”.22 The SSA-S

the ceasefire KNU/KNLA Peace Council, who leader Yawd Serk warned that “large-scale

8 | Burma Policy Briefing

civil war” might break out.23 And sporadic ENC and NCGUB to call for a new “national

but sometimes heavy fighting in several reconciliation” programme.26

border areas, especially with the KNU and

SSA-S, was evidence that insurgent struggles However, achieving a united voice between

were by no means over. armed and non-armed member groups

proved difficult. This was highlighted when

A particular new source of conflict were gov- the ENC wrote a letter to United States

ernment business schemes with Asian neigh- Senator Jim Webb after his visit to Burma.

bours, such as the proposed Hat Gyi dam in The group rejected armed struggle as a

the Karen state that was backed by both Thai- “solution” and pledged its support for

land and China.24 But during any fighting, it “eligible ethnic groups in running for office”

was usually the civilian population that to ensure a representative vote.27 Recognising

suffered the most. Despite the increasing the changing political landscape and

resettlement of refugees to third countries in emergence of new ethnic parties, not all non-

the West, official refugee numbers in Thai- ceasefire leaders agreed with an election

land remained around 130,000 (mostly Karen boycott or disruption. If they fail to keep in

and Karenni), with up to two million mi- touch with the people, history could pass

grants, both legal and illegal. insurgent and borderland groups by.

On a smaller scale, refugees and illegal mi- Community-based organisations, meanwhile,

grants also remained on the Bangladesh and viewed the growing uncertainties and threats

India borders (mostly Muslim refugees on the of new volatility in ethnic areas with deepen-

former, Chin and Naga on the latter). This ing concern. After decades of conflict, com-

scale of violence led to calls for an investiga- munity leaders advocated that all sides main-

tion into “crimes against humanity or war tain dialogue to resolve political disagree-

crimes” in Burma, an appeal subsequently ments. “The ethnic minority groups in all

echoed in a report by UN human rights regions of Burma need peace,” the Human

Special Rapporteur Tomás Ojea Quintana.25 Rights Foundation of Monland said. “The

people in ethnic regions need development to

In political terms, however, non-ceasefire improve their livelihoods, education for their

groups had to watch as bystanders while children and health care in their

electoral and ceasefire groups engaged with communities."28

the SPDC. Any future peace talks with the

KNU and other non-ceasefire forces could For Burma’s long-suffering peoples, such

only come after the election. With the NLD progress is long overdue.

and UNA boycotting the election, veteran

insurgent leaders claimed that their long- CONCLUSION

standing position of no compromise with the

military government without political In 2010, Burma is on the brink of epoch-

solutions was vindicated. But they struggled shaping change. After two decades of military

to find an effective strategy to rally rule, Than Shwe and the SPDC generals

opposition against the polls. Pressure was also finally appear ready to move ahead to the

exerted on them from neighbouring next stage of their roadmap for political

governments to maintain a low profile, the reform. Through a combination of measures,

Thai authorities several times raiding KNU continued dominance of the Tatmadaw and

and other opposition safe houses on the Thai Than Shwe’s supporters in government seems

side of the border. assured. These include marginalising the

NLD and victorious parties from the 1990

Most anti-SPDC groups along the borders election; reserving seats for military

eventually came to support the 2009 appointees and the likely victory of the USDP

formation of a Movement for Democracy and in the 2010 polls; building a new capital at

Rights for Ethnic Nationalities, bringing Nay Pyi Taw; and promoting trade and

together the broader alliances of the NCUB, energy deals with Asian neighbours. Conflict

Burma Policy Briefing | 9

and divisions among ethnic nationality ethnic areas, the new economic projects are a

groups further strengthen the military’s growing source of grievance, with local

dominance. Only, it appears, will changes communities complaining of being bypassed

within the Tatmadaw itself cause the military and excluded.30

authorities to alter course now.

A series of explosions in April 2010 that hit

targets across the country warned that resent-

ment could be rising against the military

“The ethnic minority groups in all regions of Burma government and its supporters. Various

dissident groups were accused or suspected.

need peace, and want the new government to solve Targets included a toll gate near Muse in the

Shan state; the Mytisone and Thaukyaykhat

their political problems and end armed conflicts dam projects in the Kachin state and Bago

division respectively; Loikaw police station in

through peaceful negotiations with ethnic minority the Kayah state; a telecommunications office

in Kyaikmayaw, Mon state; and the Water

armed groups. Festival in Yangon, in which 10 people were

The people in ethnic regions need development to killed and over 170 wounded. After another

two decades of military rule, Burma remains

improve their livelihoods, education for their children in a state of conflict.

and health care in their communities. ” The international community and all political

groups in Burma therefore face major

Human Rights Foundation of Monland, March 2010 challenges in their responses to the 2010

election. To date, there has been little unity

and consensus. The situation is reminiscent

Burma’s troubled history since independence of the 2008 referendum to which there was

does not portend easy or quick solutions. also a disparate response, meaning that the

Parties supporting the election believe that it proposed new constitution was never fully

could take the life of at least one parliament, faced up to, debated or approved by all

until 2015, for political progress and reforms stakeholders. The international community,

to take root. But as political momentum too, remains divided by Western policies of

gathered pace in early 2010, it became clear sanctions and Asian policies of engagement.

that not only would there be little chance of

amending the 2008 constitution but that the For these reasons, a sustained and inclusive

election would go ahead without the NLD focus is vital on the 2010 election, both within

and both ceasefire and non-ceasefire groups Burma and the international community, so

whose inclusion is integral for national that its outcome can have clear and historic

reconciliation. As at other key turning points meaning. There are three major areas by

in Burma’s history in 1948 and 1962, a new which reform transition can be adjudged:

government system is about to be introduced political, ethnic and economic.

to a backdrop of conflict and exclusion.

The political challenges include the

The starkest warnings of Burma’s plight are construction of a democratic system of

in the countrywide poverty and humanitarian government that guarantees representation

crises. Despite the growing economic links and human rights for all. The ethnic

with Asian neighbours, the military govern- challenges include conflict resolution and

ment remains among the most condemned in humanitarian progress in the most

the international community and the subject impoverished regions of the country. And the

of repeated censure by the United Nations for economic challenges include equitable

grave human rights abuses, including forced participation, sustainable development and

labour, torture and extrajudicial executions in progress that will bring benefits to every

the ethnic borderlands.29 Indeed in many district and ethnic group.

10 | Burma Policy Briefing

In summary, without such benchmarks for 13. Mizzima News, “Shwe Ohn invites political par-

inclusive reform benefiting all peoples and ties to unite for strong opposition”, 23 September

2009.

citizens being achieved, the election and

introduction of a new government are 14. NLD, “The Shwegondaing Declaration”, 29 April

2009.

unlikely to bring sustainable peace and

15. “Shan party petitions junta chief for meeting with

reconciliation to Burma.

detained leaders”, S.H.A.N., 6 January 2010.

16. UNA letter, “To H.E. Ban Ki-moon, the

Secretary-General United Nations Organization New

NOTES

York”, 16 March 2010.

1. In 1989 the military government changed the offi- 17. Kramer, Tom, Burma: Neither War Nor Peace:

cial name of the country from Burma to Myanmar. The Future Of The Cease-Fire Agreements In Burma,

They can be considered alternative forms in the Bur- Amsterdam: Transnational Institute, 5 July 2009.

mese language, but their use has become a politicised 18. Kramer, Tom, Burma’s Cease-fires at Risk:

issue. The UN uses Myanmar, but it is not commonly Consequences of the Kokang Crisis for Peace and

used in the English language. Therefore Burma will Democracy, Transnational Institute, Peace & Security

be mostly used in this publication. This is not Briefing No. 1, September 2009.

intended as a political statement. 19. Bao Youxiang, UWSA chairman, letter, “To

2. For historical analyses of the ethnic conflict, see for General Ye Myint, Our opinion and demands

example Smith, Martin, Burma: Insurgency and the concerning the problem of determination of Wa

Politics of Ethnicity, London: Zed Books, 1999; South, region boundary and transformation of troops”, 10

Ashley, Ethnic Politics in Burma: States of Conflict, November 2009.

Abingdon: Routledge, 2008. 20. Gen. Htay Maung, chairman KNU/KNLA Peace

3. Tomás Ojea Quintana, “Progress report of the Council, letter to, “Lt-Gen. Ye Myint, Chief of

Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights Military Intelligence, Naypidaw”, 22 April 2010.

in Myanmar”, Human Rights Council, 10 March 21. Kon Hadae, Independent Mon News Agency, “SEC

2010, p.17. gives NMSP a ‘pre-ceasefire relationship’

4. Thailand Burma Border Consortium, Protracted ultimatum”, 19 April 2010.

Displacement and Militarisation in Eastern Burma, 22. KNU, “Statement of 2nd Meeting of the Central

November 2009, p. 3. Committee after the 14th KNU Congress”, 22

5. Kramer, Tom, Martin Jelsma and Tom Blickman, February 2010.

Withdrawal Symptoms in the Golden Triangle: A 23. Hseng Khio Fah, “Shan rebel leader warns of

Drugs Market in Disarray, Amsterdam: large scale civil war”, S.H.A.N. 28 April 2010.

Transnational Institute, January 2009.

24. Work was halted for a time after two Thai

6. The analyses in this report are based on written engineers were killed in guerrilla attacks. See for

materials and interviews with representatives of example, Saw Yan Naing, “Survey Work Pressing

government and different ethnic groups over many Ahead at Hat Gyi Dam Site”, The Irrawaddy, 19

years. August 2009.

7. See for example, Global Witness, A Conflict of 25. Quintana, op. cit.

Interests: The uncertain future of Burma’s forests, 26. UPI, “Myanmar democracy group offers

London, 2003. alternative”, 14 August 2009.

8. See for example, speech of Vice-Senior General 27. ENC (Union of Burma), letter to Senator Webb,

Maung Aye, New Light of Myanmar, 8 January 2010. 28 September 2009.

9. See, South, Ashley. Civil Society in Burma: The 28. Human Rights Foundation of Monland,

Development of Democracy amidst Conflict, Policy No.3/2010, 31 March 2010.

Studies No. 51, Washington D. C.: East-West Center

29. See for example, Quintana, op. cit.

and Singapore: ISEAS Publishing, 2008.

10. For an analysis, see for example, International 30. See for example, Global Witness, A Disharmoni-

ous Trade: China and the continued destruction of

Crisis Group, Myanmar: Towards the Elections, Asia

Report No.174, 20 August 2009. Burma's northern frontier forests, London, 2009;

Kachin Development Networking Group, Resisting

11. See for example, Amnesty International, The the ood: Communities taking a stand against the

repression of ethnic minority activists in Myanmar, imminent construction of Irrawaddy dams,

London, 2010. www.burmariversnetwork.org, 2009; and Shwe Gas

12. NLD statement, “A message to the people of Movement, Corridor of Power: China’s Trans-Burma

Burma”, 6 April 2010. Oil and Gas Pipelines, Chiang Mai, 2009.

Burma Policy Briefing | 11

TNI-BCN Project on Ethnic Conflict in Burma Burma Policy Briefings

Burma has been afflicted by ethnic conflict and civil war since Burma in 2010: A Critical Year

independence in 1948, exposing it to some of the longest in Ethnic Politics, Burma Policy

running armed conflicts in the world. Ethnic nationality peoples Briefing No.1, June 2010

have long felt marginalised and discriminated against. The

situation worsened after the military coup in 1962, when Burma’s 2010 Elections:

minority rights were further curtailed. The main grievances of Challenges and Opportunities,

ethnic nationality groups in Burma are the lack of influence in Burma Policy Briefing No.2,

the political decision-making processes; the absence of June 2010

economic and social development in their areas; and what they

see as the military government's Burmanisation policy, which

translates into repression of their cultural rights and religious

freedom.

This joint TNI-BCN project aims to stimulate strategic thinking

on addressing ethnic conflict in Burma and to give a voice to

ethnic nationality groups who have until now been ignored and

isolated in the international debate on the country. In order to

respond to the challenges of 2010 and the future, TNI and BCN

believe it is crucial to formulate practical and concrete policy

options and define concrete benchmarks on progress that

national and international actors can support. The project will

aim to achieve greater support for a different Burma policy,

which is pragmatic, engaged and grounded in reality.

The Transnational Institute (TNI) was founded in 1974 as an

independent, international research and policy advocacy Other Briefings

institute, with strong connections to transnational social

movements and associated intellectuals concerned to steer the Burma’s Cease-fires at Risk;

world in a democratic, equitable, environmentally sustainable Consequences of the Kokang

and peaceful direction. Its point of departure is a belief that Crisis for Peace and

solutions to global problems require global co-operation. Democracy, by Tom Kramer,

TNI Peace & Security Briefing

BCN was founded in 1993. It works towards democratisation Nr 1, September 2009.

and respect for human rights in Burma. BCN does this through

information dissemination, lobby and campaign work, and the Neither War nor Peace; The

strengthening of Burmese civil society organisations. In recent Future of the Cease-fire

years the focus has shifted away from campaigning for economic Agreements in Burma. Tom

isolation towards advocacy in support of civil society and a Kramer, TNI, July 2009.

solution to the ethnic crises in Burma.

From Golden Triangle to

Rubber Belt? The Future of the

Transnational Institute Burma Centrum Netherlands Opium Bans in the Kokang and

PO Box 14656 PO Box 14563 Wa Regions. Tom Kramer, TNI

1001 LD Amsterdam 1001 LB Amsterdam Drug Policy Briefing No.29,

The Netherlands The Netherlands July 2009.

Tel: +31-20-6626608 Tel.: 31-20-671 6952

Fax: +31-20-6757176 Fax: 31-20-671 3513 Withdrawal Symptoms in the

E-mail: burma@tni.org E-mail: info@burmacentrum.nl Golden Triangle; A Drugs

www.tni.org/page/tni-bcn- www.burmacentrum.nl Market in Disarray. Tom

burma-project Kramer, Martin Jelsma, Tom

www.tni.org/drugs Blickman, TNI, January 2009.

12 | Burma Policy Briefing

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- HARVARD:Crackdown LETPADAUNG COPPER MINING OCT.2015Document26 pagesHARVARD:Crackdown LETPADAUNG COPPER MINING OCT.2015Pugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- SOMKIAT SPEECH ENGLISH "Stop Thaksin Regime and Restart Thailand"Document14 pagesSOMKIAT SPEECH ENGLISH "Stop Thaksin Regime and Restart Thailand"Pugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- #Myanmar #Nationwide #Ceasefire #Agreement #Doc #EnglishDocument14 pages#Myanmar #Nationwide #Ceasefire #Agreement #Doc #EnglishPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- #NEPALQUAKE Foreigner - Nepal Police.Document6 pages#NEPALQUAKE Foreigner - Nepal Police.Pugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Justice For Ko Par Gyi Aka Aung Kyaw NaingDocument4 pagesJustice For Ko Par Gyi Aka Aung Kyaw NaingPugh Jutta100% (1)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- ACHC"social Responsibility" Report Upstream Ayeyawady Confluence Basin Hydropower Co., LTD.Document60 pagesACHC"social Responsibility" Report Upstream Ayeyawady Confluence Basin Hydropower Co., LTD.Pugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- MNHRC REPORT On Letpadaungtaung IncidentDocument11 pagesMNHRC REPORT On Letpadaungtaung IncidentPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- HARVARD REPORT :myanmar Officials Implicated in War Crimes and Crimes Against HumanityDocument84 pagesHARVARD REPORT :myanmar Officials Implicated in War Crimes and Crimes Against HumanityPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Modern Slavery :study of Labour Conditions in Yangon's Industrial ZonesDocument40 pagesModern Slavery :study of Labour Conditions in Yangon's Industrial ZonesPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Asia Foundation "National Public Perception Surveys of The Thai Electorate,"Document181 pagesAsia Foundation "National Public Perception Surveys of The Thai Electorate,"Pugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- Davenport McKesson Corporation Agreed To Provide Lobbying Services For The The Kingdom of Thailand Inside The United States CongressDocument4 pagesDavenport McKesson Corporation Agreed To Provide Lobbying Services For The The Kingdom of Thailand Inside The United States CongressPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- United Nations Office On Drugs and Crime. Opium Survey 2013Document100 pagesUnited Nations Office On Drugs and Crime. Opium Survey 2013Pugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- BURMA Economics-of-Peace-and-Conflict-report-EnglishDocument75 pagesBURMA Economics-of-Peace-and-Conflict-report-EnglishPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Children For HireDocument56 pagesChildren For HirePugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- Laiza Ethnic Armed Group Conference StatementDocument1 pageLaiza Ethnic Armed Group Conference StatementPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- U Kyaw Tin UN Response by PR Myanmar Toreport of Mr. Tomas Ojea QuintanaDocument7 pagesU Kyaw Tin UN Response by PR Myanmar Toreport of Mr. Tomas Ojea QuintanaPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- Myitkyina Joint Statement 2013 November 05.Document2 pagesMyitkyina Joint Statement 2013 November 05.Pugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- Rcss/ssa Statement Ethnic Armed Conference Laiza 9.nov.2013 Burmese-EnglishDocument2 pagesRcss/ssa Statement Ethnic Armed Conference Laiza 9.nov.2013 Burmese-EnglishPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- UNODC Record High Methamphetamine Seizures in Southeast Asia 2013Document162 pagesUNODC Record High Methamphetamine Seizures in Southeast Asia 2013Anonymous S7Cq7ZDgPNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Poverty, Displacement and Local Governance in South East Burma/Myanmar-ENGLISHDocument44 pagesPoverty, Displacement and Local Governance in South East Burma/Myanmar-ENGLISHPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- MON HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT: DisputedTerritory - ENGL.Document101 pagesMON HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT: DisputedTerritory - ENGL.Pugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- KNU and RCSS Joint Statement-October 26-English.Document2 pagesKNU and RCSS Joint Statement-October 26-English.Pugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- KIO Government Agreement MyitkyinaDocument4 pagesKIO Government Agreement MyitkyinaPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- Karen Refugee Committee Newsletter & Monthly Report, August 2013 (English, Karen, Burmese, Thai)Document21 pagesKaren Refugee Committee Newsletter & Monthly Report, August 2013 (English, Karen, Burmese, Thai)Pugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- Ceasefires Sans Peace Process in Myanmar: The Shan State Army, 1989-2011Document0 pagesCeasefires Sans Peace Process in Myanmar: The Shan State Army, 1989-2011rohingyabloggerNo ratings yet

- Brief in BumeseDocument6 pagesBrief in BumeseKo WinNo ratings yet

- SHWE GAS REPORT :DrawingTheLine ENGLISHDocument48 pagesSHWE GAS REPORT :DrawingTheLine ENGLISHPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- The Dark Side of Transition Violence Against Muslims in MyanmarDocument36 pagesThe Dark Side of Transition Violence Against Muslims in MyanmarPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- TBBC 2013-6-Mth-Rpt-Jan-JunDocument130 pagesTBBC 2013-6-Mth-Rpt-Jan-JuntaisamyoneNo ratings yet

- Taunggyi Trust Building Conference Statement - BurmeseDocument1 pageTaunggyi Trust Building Conference Statement - BurmesePugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- R 250 KH Thao Dien Q2Document19 pagesR 250 KH Thao Dien Q2kitty2ponNo ratings yet

- Ufo WalkthroughDocument7 pagesUfo WalkthroughBrian BestNo ratings yet

- A National Security Strategy OF AND: Engagement EnlargementDocument41 pagesA National Security Strategy OF AND: Engagement EnlargementpuupuupuuNo ratings yet

- Russian GaugeDocument3 pagesRussian Gaugemow007No ratings yet

- American Air Power Strategy in WWII PDFDocument290 pagesAmerican Air Power Strategy in WWII PDFGotonielNo ratings yet

- Janes - 2009 - ChinaDocument655 pagesJanes - 2009 - ChinapaulakansasNo ratings yet

- Filling A Gap: The Clandestine Gang Fixing Rome IllegallyDocument2 pagesFilling A Gap: The Clandestine Gang Fixing Rome IllegallypentitiNo ratings yet

- NELSON MANDELA Worksheet Video BIsDocument3 pagesNELSON MANDELA Worksheet Video BIsAngel Angeleri-priftis.No ratings yet

- Attractions Magazine Fall 2015 PDFDocument64 pagesAttractions Magazine Fall 2015 PDFattractions magazineNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- AlcazarDocument18 pagesAlcazargbaeza9631No ratings yet

- BLAS 140B (89701) SyllabusDocument6 pagesBLAS 140B (89701) SyllabusdspearmaNo ratings yet

- Ancient RomeDocument228 pagesAncient RomeLudwigRoss88% (26)

- Hybrid - ENG - FOR WEB 02Document284 pagesHybrid - ENG - FOR WEB 02OlaNo ratings yet

- Chinese Revolution The Biggest Genocide On Planet Earth, Communism and The Jews, Mao Tse Tung and Rothschild Funds - Capt Ajit VadakayilDocument64 pagesChinese Revolution The Biggest Genocide On Planet Earth, Communism and The Jews, Mao Tse Tung and Rothschild Funds - Capt Ajit VadakayilAnonymous00007No ratings yet

- Peace Is A Resistance To The Terrible Satisfactions of WarDocument30 pagesPeace Is A Resistance To The Terrible Satisfactions of WarJuan Carlos SabellaNo ratings yet

- 998micro0311b PDFDocument40 pages998micro0311b PDFcpt_suzukiNo ratings yet

- DdressDocument59 pagesDdressTiger HabibNo ratings yet

- Mughal NotesDocument35 pagesMughal NotesKainat Tufail100% (1)

- Admiral David KirkeDocument3 pagesAdmiral David KirkeSubhash ChopraNo ratings yet

- A Need To KnowDocument234 pagesA Need To KnowBob Andrepont100% (1)

- Religious Ideologies and Tax Evasion in Somalia The Case of SomaliDocument77 pagesReligious Ideologies and Tax Evasion in Somalia The Case of Somaliaial somaliaNo ratings yet

- X-Universe - Rogues Testament by Steve MillerDocument281 pagesX-Universe - Rogues Testament by Steve MillerRoccoGranataNo ratings yet

- Brock, Roger-Greek Political Imagery From Homer To Aristotle-Bloomsbury Academic (2013)Document273 pagesBrock, Roger-Greek Political Imagery From Homer To Aristotle-Bloomsbury Academic (2013)juanemmma100% (1)

- National Security Law OutlineDocument76 pagesNational Security Law OutlinemoonNo ratings yet

- Cavitation & Super Cavitation: Intersting PhenomentomnDocument27 pagesCavitation & Super Cavitation: Intersting PhenomentomnAnonymous kRbbzLNo ratings yet

- North Korea Under Kim Chong-Il Power, Politics, and Prospects For ChangeDocument256 pagesNorth Korea Under Kim Chong-Il Power, Politics, and Prospects For ChangeLaur Goe100% (3)

- ListDocument64 pagesListMuchlisar FebriantoNo ratings yet

- Mesbg - Armies-Of-The-Hobbit - Designer-Commentary (Aug 2020)Document3 pagesMesbg - Armies-Of-The-Hobbit - Designer-Commentary (Aug 2020)argonia6100% (1)

- JTNews - April 15, 2011Document44 pagesJTNews - April 15, 2011Joel MagalnickNo ratings yet

- Whitman As A Representative PoetDocument6 pagesWhitman As A Representative PoetDipankar Ghosh100% (1)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (28)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.From EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (110)

- 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedFrom Everand1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (111)

- Briefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndFrom EverandBriefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndNo ratings yet

- Selling the Dream: The Billion-Dollar Industry Bankrupting AmericansFrom EverandSelling the Dream: The Billion-Dollar Industry Bankrupting AmericansRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- Prisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldFrom EverandPrisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1145)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryFrom EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (44)