Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Camp Reg Her

Uploaded by

FacundoPMCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Camp Reg Her

Uploaded by

FacundoPMCopyright:

Available Formats

Shifting Perspectives on Development: An Actor-Network Study of a Dam in Costa Rica

Author(s): Christoph Campregher

Source: Anthropological Quarterly, Vol. 83, No. 4 (Fall 2010), pp. 783-804

Published by: The George Washington University Institute for Ethnographic Research

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40890839 .

Accessed: 27/02/2014 11:40

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The George Washington University Institute for Ethnographic Research is collaborating with JSTOR to

digitize, preserve and extend access to Anthropological Quarterly.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 200.123.187.130 on Thu, 27 Feb 2014 11:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ShiftingPerspectives on

Development: AnActor-Network

Studyof a Dam in Costa Rica

ChristophCampregher

Universityof Vienna,Austria

Universityof Costa Rica

Abstract

Thearticleconcernsthepoliticalnegotiations duringtheplanningprocessof

a hydroelectric dam whoseconstruction affectsan indigenouscommunity

in Costa Rica. In orderto allow the thickdescriptionof thisdevelopment-

network,the study traces how threeactors in the field- development

workers,indigenousactivists,and an independentresearcher - produce

culturalrepresentations and conceptswithapparentlyclear boundaries.

Thismultivocalaccountshowshow developmentprojectsconstitutethem-

selves by associatingheterogeneousactors. Simultaneously, it highlights

theproductionof culturalrepresentations and knowledgeof development.

[Keywords:anthropologyof development,Actor-Network Theory,chains

of translation,El Diquis, Costa Rica, hydroelectrical

dam, Trraba]

AnthropologicalQuarterly,Vol. 83, No. 4, pp. 783-804, ISSN 0003-549. 2010 by the Institutefor Ethnographic

Research (IFER) a part of the George WashingtonUniversity.All rightsreserved.

783

This content downloaded from 200.123.187.130 on Thu, 27 Feb 2014 11:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ShiftingPerspectiveson Development: An Actor-Network

Studyof a Dam in Costa Rica

L Introduction

The anthropological study of development, anthropology's "evil twin"

(Ferguson 1997a), has gained increasing importance and recognition as a

distinct subfield of anthropology as a discipline. Lewis and Mosse (2006)

distinguish three approaches in the anthropology of development: (a.)

instrumentalones, which promote social progress through the means of

more effective development interventions, institutional reforms,or the

establishment of new methods; (b.) deconstructivistapproaches, which

criticize development politics and economics as a distinct hegemonic dis-

course (Escobar 1995, Ferguson 1997b, Sachs 1992); and (c.) sociological

interactionism,which promotes a sociology of development based on the

empirical investigation of the interactions between developers, devel-

opees, and the "brokers" in between (Arce and Long 2000; Bierschenk,

Chauveau, and Olivier de Sardan 1999; Olivier de Sardan 2005). This paper

takes some insightsfrom Actor-NetworkTheory (ANT)to show, first,how

these three approaches can be combined to give a more complex picture

of development processes, and second, that each one of them reflectsthe

perspectives of actors' positions in the development context.

In the second half of 2006, I had the opportunityto study the negotia-

tions between an indigenous communityand a planned dam in southern

Costa Rica. For this study (Campregher 2008), I chose an interactionist

approach, taking the standpoint of a neutral outside observer. In the pres-

ent article, I want to reinterpretthis study based on a relational approach

informed by Actor-NetworkTheory and on the principle of symmetry

which states that scientific practice needs to be treated in the same way

as any other practice. The aim of this reinterpretationis to present the

anthropologist's interpretationson the same level as the descriptions and

interpretationsof the actors and informants(relativism), and finally to

interpretall together as different,but equally valid attempts to establish

and maintain networks(relationism).

To shiftthe observers' perspectives in the present case study will allow

us to combine some advantages of the three aforementioned paradigms

while avoiding some of their shortcomingsand "blind spots." In order to

provide a "thick description" (Geertz 1973) of the Costa Rican dam proj-

ect, I present the interpretations and points of view of the central

actors- development workers, indigenous activists, and an independent

researcher- including their reflectionson their own positions and those

of their respective counterparts. Each of these perspectives on develop-

784

This content downloaded from 200.123.187.130 on Thu, 27 Feb 2014 11:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CHRISTOPH

CAMPREGHER

mentwill be shownto correspondto the threeanthropologicalapproach-

es cited above. Finally,the actors,theirpractices,and discourseswill be

shownto formpartsof different chainsof translation(Latour1999).

IL Actor-NetworkTheory and the Study of Development

A growingnumberof studiesfromthe field of Science and Technology

Studies(STS)have arguedthatscientificpracticedoes notdifferprincipal-

lyfromotherordinaryand mundanepracticein the sense of permitting

usa privilegedinsightinto"reality"or "nature"(Bloor1991; Calln1986;

Latour1987, 1999). Ratherit is the specificconditionsand the contextsof

the productionof scientificknowledgewhich account for its status as

"true" facts. Scholars of STS emphasize, therefore,a sociologywhich

investigatesscience in the makingor as practicein the same wayanthro-

pologistswould studyanyotherkindof activity(Latour1987). One of the

consequencesof this positionis to adopt the principleof symmetry pro-

moted by Bloor (1991) that states that "true" knowledge must be

explainedbythe same conceptsas knowledgethatis considered"false."

Actor-Network Theoryis one approach in the fieldof STS. It aims to

overcomethe dichotomousdistinctionbetween nature/technology and

societybyusing a notion of networks that include human and non-human

agents.Their"network"conceptservesto describe basicallyany assem-

blage of at least threeelementsthat are in any way connected. Its ele-

mentsare humansand objects,whichneed to be treatedsymmetrically

bythe researcher{generalizedsymmetry) (Schulz-Schaeffer 2000).

Adopting these of for

principles symmetry anthropology would meanto

apply the same language to (1.) rightand wrongstatements(truthand

errorsor knowledgeand belief);(2.) humanbeingsand materialobjects(in

orderto overcomethe nature-society divide);(3.) westernand non-western

societies;and (4.) anthropologicaland non-anthropological practice.The

anthropologist should treatthem in the same way and explain them by

using the same kindof factorsand concepts(Rottenburg 1998:62-64).An

anthropology based on theseprinciplesofsymmetry promisesto overcome

notonlythe modernwesternphilosophywhichconceptualizesnatureand

societyas twodistinctspheres,butalso the granddividebetweenmodern

and primitive or premodernsocietiesbyframingthemas collectivesthat

integratea different numberof humanand non-humanbeings,and which

constructtheircosmologiesaroundthem(Latour1993). This is one of the

785

This content downloaded from 200.123.187.130 on Thu, 27 Feb 2014 11:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ShiftingPerspectiveson Development: An Actor-NetworkStudyof a Dam in Costa Rica

reasons why STS and especially Actor-NetworkTheory are increasinglyrel-

evant for the anthropological study of development (Mosse 2005,

Rottenburg2009, Weilenmann 2005). These studies do not claim any prin-

cipal differencebetween western culture or expert knowledge, on the one

hand, and local knowledge or culturallyconstrained beliefs, on the other

hand, which in conventional development thinkingoften represent possi-

ble obstacles of development success or reasons for project failure.

Treating anthropological practice in the same way we treat any other

kind of practice has at least two consequences. First,we cannot make a

difference between the opinions or considerations of anthropologists

when they speak or write about a development project (or other aspects

of society) and those of people from other professions and backgrounds.

All are products of specific circumstances and are equally positioned. As I

will show, every one of the three anthropological approaches mentioned

above, identifieswith a specific actor's position or standpoint fromwhich

development is observed- be that the developers, the developees, or the

one of an observer from "outside." Consequently, neither one of them

can be considered as more objective than the others, as that would mean

that there would be actors in the development arena that see realitymore

directly, more objectively, or more "truly" than others. It would also

mean to establish an asymmetryof viewpoints a priori to the investiga-

tion, which is exactly what we should avoid. I propose to integrate insights

from all actors' positions by switching between the three mentioned

approaches and to combine them using a relational approach, as Actor-

Network Theory suggests (Latour 1999, 2005). Second, if scientific

accounts are positioned no differentlyto how other actors' accounts are,

than we should striveto include various accounts in the description of spe-

cific phenomena, either by integratingthem as far as that is possible or,

as I opt for, by alternating them by shiftingthe observers' perspectives

and their corresponding frames of reference.

What do I mean by "shiftingthe perspectives?" Everyaccount of reali-

ty not only depicts reality,but always orders the way in which we perceive

it. As a consequence, every representation has its blind spot: it cannot

observe either its own position or its own differentiationsand classifica-

tions. If we cannot get rid of the blind spots, at least we can tryto place

them differently.So, instead of getting lost in endless and complex

debates about definitions of reality,we can change, or shift,the observ-

er's positions according to the goals of our study (Rottenburg2009).

786

This content downloaded from 200.123.187.130 on Thu, 27 Feb 2014 11:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CHRISTOPH

CAMPREGHER

Forthe presenttext,thatmeansthe following:

(1.) Instead of describingour case studyof the politicalnegotiations

betweena planneddam and an indigenouscommunity conventionallyfrom

the viewpointof the anthropologist and tryingto confirmmyaccount by

citingexcerptsand passagesof interviews, I will illustratethe representa-

tionsoftheactorsor actorgroupsas theyweregivenbythem(sectionsIII.I

and III.II). Followingthis,theviewpointofthe researcher (sectionMINI)will

be treatedand presentedin thesame wayas the non-sociological accounts.

(2.) As I willshow,the threeperspectivesof the actorsin the case study

correspondwiththe three anthropologicalapproaches describedabove

(instrumentalanthropology,criticaldeconstructivism, and sociological

interactionism) in its positioningand itsview on the phenomenon.

all

(3.) Finally, threeactor groupscontributeto the constitutionof a

unifiedrepresentation of the dam project,and all act as elementsin larg-

er chains of translation.The last part (III.IV) describes how the actors

develop theirrepresentations and how theyinteractwithotherelements

in the network.

III. Case Study: To Develop a Dam

The context of our case study is a hydroelectricalproject called

Hydroelectrical ProjectEl Diquis^ or PHEDforitsinitiallettersin Spanish,

whichis planned to be constructedin southernCosta Rica,and the con-

structionof which affectsthe indigenouscommunityof Trraba. The

mainactorsare sociologistsand anthropologists who are employedbythe

projectto workon and withthe affectedpopulation,indigenousoppo-

nentsto the project,and an independentresearcher.The sociologistsand

anthropologistsof the PHED confrontthe question of how to mediate

betweenrivalgroupsin Trrabaand the project'sexecutives(instrumen-

tal approach).In the followingsection(III.I), I will let themspeak to the

readerin orderto describethe projectand the difficulties theyconfront.

A coalitionof indigenousactivistsin Trrabacategoricallyrejectsthe

construction of the dam. They"deconstruct"the plans and argumentsof

its representatives,demandingin its stead the rightto realize theirown

ideas of an autonomous indigenousdevelopment(criticaldeconstruc-

tivism).In sectionIII.II, these criticswill be presented.Thissectionis fol-

lowed bya descriptionof the independentethnographer's (interactionist)

positionas outsideobserver(III.III).

787

This content downloaded from 200.123.187.130 on Thu, 27 Feb 2014 11:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ShiftingPerspectiveson Development: An Actor-NetworkStudyof a Dam in Costa Rica

All positionsare similarin the sense thattheyproduceculturalrepre-

sentationsof the same social reality,representationswhichtheyperceive

as real and genuine. In addition, all of them translateand mediate

betweenrealityand its representations (Latour1999). In the last section

(III.IV),I willshowwhythe actorsdepend on each other,whiletheytryto

establishdifferent and competingrepresentations of reality.

///./Developmentand its Promoters

Atthe end of2004 the CostaRicanElectricity Institute (ICE)2presentedthe

latestversionof a seriesof plansto constructa dam forthe productionof

in the country'sSouthernPacificregion.This project,whichis

electricity

titledHydroelectrical ProjectEl Diquis (PHED),aims to constructa dam at

the Trraba Riverwhichbordersthe recognizedindigenousterritory of

the same name. Witha lake of approximately six thousand hectares,it

shouldproducemorethansix hundredmegawattsof electricity forwhich

it needs the investmentof about 1.85 millionUS Dollars (Artavia2008,

InstitutoCostarricense de Electricidad2006).

In general,theargumentsin the project'spolicydocumentsaim to con-

vincepowerful actorssuchas politicians, transnational corporations,inter-

nationalorganizations,investorsor opposingenvironmental groups,and

non-governmental organizations(NGOs).Theyargue the necessityof the

projectformeetingthe country'srisingdemandforenergy,and promote

theproject'sbenefits forthepoorregion'seconomy,possibilities ofemploy-

ment,infrastructure, and opportunities forlocal tourism.Atthesame time,

theyrespondto criticalvoices fromconservationist organizationsby pre-

senting measures to reduce environmental impact and damages.

To establishthe contactwiththe ruralpopulationin the projectarea,

the ICE maintainsa special departmentas partof the project'sorganiza-

tionalstructure, the Departmentof Social Investigation. In an one-storied

building in the provincecapital Buenos work

Aires, about a dozen devel-

opmentworkerswithsociologicalbackgrounds, and their Their

assistants.

taskscan be dividedintothreedomains: (a.) informing affectedpopula-

tionsabout the project;(b.) researchon the population;and (c.) coordina-

tion withaffectedcommunitiesthroughtheirown representatives. The

argumentsof the project'spolicyplans are hardlyusefulto convince the

affectedpeople of its benefitsas theygenerallyargue in the name of a

ratherabstractnationalinterestand macro-economic advantages.It is the

project'ssocial scientists'taskto translatethese plans intoconcretestate-

788

This content downloaded from 200.123.187.130 on Thu, 27 Feb 2014 11:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CHRISTOPH

CAMPREGHER

mentsand to findanswersto the questionsof worriedfarmersand ambi-

tiouscommunity leaders.

Amongthe populationin the projectarea, the indigenouscommunity

of Trraba is one of the mostdifficultones. The specificproblemsthat

arose for the PHED in Trraba are primarilydue to the community's

indigenousidentityand the specificlegal characterof its recognizedter-

Ata meeting,the social scientistsat the PHEDdescribeitsspecific

ritory.

relevanceas follows:

Reportof the Membersof the DepartmentforSocial Investigation3

In Trraba, there exist various organized groups which compete

among themselves.Each groupclaims to representthe indigenous

community or partsof it, and simultaneouslyquestionsthe legiti-

macyof othergroups.We originallyworkedwiththe Associationof

Integral Development (ADI),4which according to Costa Rican

IndigenousLaw is the legallyrecognizedinstitution that represents

theterritory.5 The indigenousterritory ofTrrabais subjectto a spe-

cificlegislation,establishedbythe Costa RicanIndigenousLawand

internationalconventionssuch as the ILO Convention169.6 For

example, inside the legallyestablishedterritory land can only be

owned byindigenouspeople and can onlybe tradedbetweenthem.

Nevertheless,in the past the legal normswere not successfully

implementedand executed,and so it comes,thattodayonlyabout

ten per cent of Trraba'sland is actuallypossessed by indigenous

persons.The majorityof the land is in the handsof non-indigenous

colonists,althoughtheycannotclaim any legal titleto it. Thissitu-

ation has led to a seriesof long lastingproblemsand conflicts.

Otherexistinggroupsin the community formthe politicaloppo-

sitionto the ADI and its leaders' politics.Theyargue thatthe ADI is

an institution imposedbythe stateand, therefore,rejectit. Instead

theyclaim the rightto formtheirown organizationsindependently

and to promotetheirvisionsof developmentautonomouslyof the

state. These oppositional groups frequentlyrefer to the ILO

Convention169, ratifiedby Costa Rica in 1992, which recognizes

specificrightsof indigenouspeoples. The majorityof theirleaders

rejectedthe PHED in the past.

In 2005, the ICEneededto completegeologicalstudiesat thewest-

ernriverside oftheTrrabariverinsidethe indigenousterritory. The

789

This content downloaded from 200.123.187.130 on Thu, 27 Feb 2014 11:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ShiftingPerspectiveson Development: An Actor-Network

Studyof a Dam in Costa Rica

affectedarea is propertyof a non-indigenoussettler. Initially,the ICE

got permission from both the ADI which legally representsthe com-

munityand itsterritory,and fromthe individual landowner. However,

shortlyafter the ICE began to carry out the studies, a coalition of

opponents fromthese independent indigenous groups denounced the

ICE's actions at Costa Rica's Supreme Court.7They argue, first,that the

excavations and explorations which the ICE undertook affect the

water quality of the Trraba River negatively.Second, according to

the ILO Convention,the state must consult the indigenous population

if it is to undertake any legislative or administrative action that

affectsit or its territory.Anyconsultation must, so these indigenous

leaders, include the whole communityor at least representativesfrom

all of the organizations that exist in Trraba. Therefore,they argue

the ICE has not yet consulted the community.As a consequence, the

studies would violate their fundamental rights.

As a reaction, the ICE has stopped the studies until the complaint

should be resolved. We, the Department of Social Investigation,

established working relations with all organized groups in Trraba,

some of them maintain a more cooperative position while others

are more critical. One of our current projects is an ethnography of

Trraba in which we want to focus on the ideas and concepts of

development that exist among the communitymembers and its fac-

tions. The results will be compared to the ICE's notion of develop-

ment and to the possibilities of convergence of these seemingly

opposing visions, in order to build on stronger relations with and

among the community's organizations

In the mid-term,we aim to establish a common legitimate plat-

form, in which all of the rivaling groups participate, in order to

facilitate the coordination with them. In the future, this platform

should define the indigenous community's position regarding the

project on common grounds based on information, rather than

rumors and misinterpretationas has been the case in the past.

Another difficultyhas been to integrate the social dynamics of

this specific case into the project's plans and strategies. It has

proven difficultto communicate complex social issues inside an

organization that is predominantly composed of people with back-

grounds in economics and engineering. Having to deal with cultur-

ally differentpopulations is a relatively new issue for the ICE. For

790

This content downloaded from 200.123.187.130 on Thu, 27 Feb 2014 11:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CHRISTOPH

CAMPREGHER

manyexecutives,it has been surprising thata relativelysmallgroup

of ruralpeasants (as theyperceiveTrraba)can stop or delay the

project's activities.So, our effortsare to integratethe complex

social realityinto the project'spolicyplans and strategies,on the

one hand,and to raise consciousnessforthe complexissues related

withindigenouspeoples such as Trraba,on the other.

(End of the reportof the PHED's social scientists.)

In short,the sociologistsand anthropologists confrontthe following

challenges:Theyneed to carefullybuilda trustingrelationshipwitheach

one of the conflictingfactions,whichtheyshould then integrateinto a

decision makingprocess.They mustdefinecommongoals whichcould

serveto connectthe projectand thedifferent groupsin orderto avoid the

escalatingof existingconflictsand rivalries.Thesegroupsare to be helped

in theireffortsand tasks in orderto build relationsof trustand confi-

dence. Local visionsof developmentneed to be investigatedin orderto

define where they can meet with the ICE's vision. The significanceof

social factorsneed to be increasedin the planningprocessof develop-

ment projects,and consciousnessfor ethnicdifferenceand indigenous

rightsmustbe promotedinsidethe ICE.

Theirapproach representsthe instrumental paradigm,similarin kind

to the accounts which Euro-American anthropologistsadopted in their

engagement in multilateraldevelopmentinstitutions such as the World

Bank(Horrowitz 1996). In thesecases, sociologistsor anthropologists

were

mediatorsbetweenthe plans of these institutions and the complexreali-

ties in whichtheyare to be implemented.Theycan be seen as "brokers"

or "translators"(Lewis& Mosse2006) in the developmentcontext.

///.//Deconstruction

The ICE'splans forthe constructionof the dam have provokedopposition

froma groupof indigenousTrrabas.The "Frontagainstthe PHED" is an

alliance of indigenousleaders of Trraba.SupportedbyvariousNGOs,it

organizes periodic meetings,assemblies, press conferences,and other

activitiesto statetheirdiscontentwiththe project.In theirconversations

and publicspeeches theycriticizehow the ICEapproachesthe communi-

ty,the project,and theirunderlying notionof development.

Theirargumentsemphasizethe negativeeffectsof the projecton the

region'secology,and theconflictsthatmayariseas a resultofthe presence

791

This content downloaded from 200.123.187.130 on Thu, 27 Feb 2014 11:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ShiftingPerspectiveson Development: An Actor-Network

Studyof a Dam in Costa Rica

of even larger numbers of non-indigenous migrantworkers. Many of the

older Teribes recall their largely negative experiences when the firstwave

of non-indigenous settlers came during the construction of the Inter-

American Highwayin the 1960s (Guevara and Chacn 1992, Amador 2002).

The conflictingrelations between these two ethnic groups and the still mar-

ginal position of indigenous peoples in Costa Rican society are the reasons

forthe last one's skeptical attitude towards the state's development policy.

Contraryto this policy, their spokespersons promote a vision of an

autonomous and auto-determined indigenous development that consid-

ers cultural, ecological, and economic factors- instead of emphasizing

exclusivelythe last one. They demand access to key resources which other

regions or social groups have, such as land or capital in the formof cred-

its or special funds. Instead of exploiting natural resources, they suggest

conserving them to benefit from them in the long run. Eco-tourism,the

promotion of research of the still existing biological diversity,and organ-

ic agricultureare considered alternatives that may be economically viable

without destroying their environment. The indigenous leaders say that

promoters of the PHED argue in terms of economic benefits and techno-

logical modernization. But they in turn experienced the modernization

process as one of integrationinto the Costa Rican society as the most mar-

ginal and underprivileged group. The benefits promised by the project do

not meet their needs because these benefits would not bring any change

in their relation with the state and the rest of society.

Supported largely by non-governmental organizations and programs,

various groups in Trraba work in the reforestation and protection of

their tropical forestsand tryto practice their agriculture in an ecological-

ly sustainable way. In their opinion, the construction of a dam would

reverse many of their achievements. As a result of these considerations,

they reject the project and its underlyingconcept of development.

The indigenous critics are against the PHED's concept of development

because it considers exclusively economic benefits. The project operates

on the basis of massive investment in infrastructureand technological

modernization for the extraction of value at the cost of the environment

and in form of a top-down interventionthrough an external enterprise.

Development in this understanding means modernization, economic

growth,and restructuringa rural, peripheral region.

The indigenous leaders, on the contrary,constructa differentvision of

development that considers cultural, social, and economic factors. It is

792

This content downloaded from 200.123.187.130 on Thu, 27 Feb 2014 11:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CHRISTOPH

CAMPREGHER

based on equal access to land,education,and capitalforindigenousfami-

lygroups,smallassociations,and cooperatives.Anditshouldbe conducted

in the formof autonomouslyadministrated programsthatwould be inde-

pendent of external institutions

and the influenceof morepowerful actors.

Developmentin thisviewis a self-determined, autonomousprocessthatis

preventedbycertainobstacles, butcan be pushedoffifmarginalgroupsor

regionsare providedequal access and rightsto keyresources.

In the presentcase, the indigenousopponentsof the dam question

the argumentsand the ideologyof the ICEand the underlyingnotionof

development.Theyprovideus witha deconstructivist response.Forthe

argument of this article,this means that,firstly,developmentinterven-

tionsdo not necessarilytake place withoutthe active resistanceof some

of the people theyaffect;and, secondly,that in practicediscoursesare

neverabsolute and all-comprising as some postmodernist studieswould

suggest(Escobar1995, Ferguson1997b), but always contested.Third,it

does not need an anthropologist to unmaskthe developmentdiscourses.

I suggestthat anthropologistsshould look forthe "real" opponents of

these interventions and documenttheirdeconstructivepracticeempiri-

cally, instead of speaking for them by puttingoneself in their place

(Olivierde Sardan 2005:112).

///.///ObservedfromOutside

The PHEDnotonlyprovokesopposition,butalso attractsthe attentionof

externalresearchers(Amador2002, Caldern2003). Foran anthropolog-

ical study,a Europeanresearcheradopts the perspectiveof the interest-

ed, but objective ethnographer(Campregher2008). His aim is to study

the relation between the PHED and the indigenous community,to

describe it as objectivelyand uncompromisingly as possible, and to

explainthe actor's positionsor discoursesin sociologicaltermswithref-

erenceto conceptsand theories.Thisallows himto describethe ongoing

negotiationfroma differentangle than both the developmentagents

and the opponents.

The ADI-Trrabais, as the membersof the PHED already mentioned,

the legal representationof Trraba. Its leading committeeis elected by

its members,but- so the criticssay- has been unchangedforfourcon-

secutiveperiods.Althoughonlya relativelysmall partof Trraba'sadult

populationis affiliatedto thisorganization,itsleaders claimto represent

the whole community.Besides ADI-Trraba,thereexistabout ten other

793

This content downloaded from 200.123.187.130 on Thu, 27 Feb 2014 11:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ShiftingPerspectiveson Development: An Actor-Network

Studyof a Dam in Costa Rica

groups, which call themselves "civil organizations." They constitute

themselves formally as associations and for the most part recruit their

supporters among kin members. The majority of their speakers are sen-

ior male heads of central households of these extended families. In coop-

eration with external organizations and support programs they organize

environmental projects, educational workshops, the production of hand-

icraft,and other communal activities. They are activists in indigenous

organizations, and participate in national or international activities,

meetings, and conferences. While the ADI sometimes tried to cooperate

with the PHED, at least when they felt doing so could strengthen their

own positions or bring benefits in exchange, the majority of the civil

groups reject the PHED.

The relation between these civil groups is itself characterized by ten-

sions and rivalry.Althoughfor the most part they reject both the ADI and

the PHED in favor of more radical indigenous politics which demand the

recognition of indigenous rights and autonomy as stated in the ILO

Convention169, they hardlysucceed in joining stable alliances or in choos-

ing either a common spokesperson or a unified organization. Rather,they

preferto maintain their separate associations in which they work along

familyaffiliationsin separate projects with the same aims. Only in some

cases do theyjoin in strategicalliances in favor or against specific topics.

The negotiation between the PHED and Trraba reflectsthese unstable

dynamics and includes a multitude of groups, persons, and their rivalries.

This complex political situation is the outcome of a historical process.

According to Henri Pittier (Gatschet 1894:218), who visited the region of

today's Buenos Aires at the end of the 19th century,Trraba at that time

was a small settlement of people fromdifferentethnic groups, who were

originallytaken to this place by Franciscan missionaries. In this conglom-

erate of different cultures, the Teribes or Trrabas, which originally

inhabited the north-westcoast of Panama, were the biggest group, which

in turn gave the settlement its name. The influence of the Catholic church

and its priests, who lived among the Trrabas, and of mestizo migrants

from Northern Panama, had the consequence that this "newly created"

indigenous group did not develop any coherent political organization that

could unite the whole communityto act collectively against intruders.

In the 1970s, the Teribes therefore rapidly adopted the legal ADI-

structurewhich was introduced by the state, followed by conflicts about

its leadership and membership in which indigenous and non-indigenous

794

This content downloaded from 200.123.187.130 on Thu, 27 Feb 2014 11:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CHRISTOPH

CAMPREGHER

groups confronted each other. Nevertheless, this institutionproved to be

hardly adequate and ineffectivefor the defense of the indigenous com-

munity's rightsand interests before the state and non-indigenous settlers

(Guevara & Chacn 1992). As a result of the growing acknowledgment of

indigenous peoples' rights in international human rights debates and

new possibilities through development cooperation, some indigenous

leaders in Trraba began to dissent from the ADI and create their own

indigenous associations. Originallycreated as a necessary preliminaryto

entering into cooperation with outside NGOs, these associations today

represent the most common form of political organization. Although

they are registered formallyas civil associations, in the majority of cases

their members recruit from the extended family of these founders. So,

they can be interpreted as a new type of organization that is simultane-

ously the result of processes of both resistance (Scott 1985), as they devel-

oped in opposition to the state's politics, and adaption to developing

relations with international civil society.

Given the limited possibilities for economic enterprise in Trraba, the

establishment of an indigenous association can be interpretedas a prom-

ising alternative for indigenous families that allows them to attract proj-

ect cooperations, donations, or fundingwhile maintaining a critical posi-

tion when confrontedwith the state's institutions.As a consequence, each

of these family associations fulfill political and economic functions for

their members as well as for the community(Campregher 2008:99).

In the same manner, some indigenous leaders' resistance to the PHED

can be seen as part of a strategyof adaption to the emergence of other

kinds of intervention, for example, to environmental or human rights

NGOs, whose interests are more compatible with indigenous ones. The

same can be said for the actual ADI-leadership. These politicians adapted

to the possibilities and institutional environment of the state structure

and thereforeresistany political project that could bringabout change in

this institutionalarrangement. That is why they heavily oppose and dele-

gitimize any other indigenous association or legal measures and reforms

that would change the existing structure.

The researcher perceives the political negotiation process between the

PHED and the indigenous communityas an arena in which various actors

with contradicting interestsand strategies confronteach other. Based on

his case study he concludes that the perception of development interven-

tions by affected populations is shaped by local necessities, existing con-

795

This content downloaded from 200.123.187.130 on Thu, 27 Feb 2014 11:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ShiftingPerspectiveson Development: An Actor-Network

Studyof a Dam in Costa Rica

flicts,historicexperience,and envisionedalternativesto this interven-

tion."Communities" or "cultures"are notclosed,autonomouslyfunction-

ingsystemswhichprojectsintervenein fromthe outside.Rather,theyare

assemblies of actors that tend to extend their relationswith external

actors and across geographical boundaries. Actorsin a development

arena adapt theirstrategiesand discoursesin orderto encourageinter-

ventionsbypowerful,externalpartners.Simultaneously theyoppose and

resistinterventionsthatcould countertheirinterestsor weaken existing

coalitionsand partnerships.

IIUV Mediators,Translation,and theActorNetworkPHED

We have adopted threedistinctperspectivesto describedifferent aspects

of the complexrelationshipbetweenthe PHEDand Trraba.Each one of

themhas itsown focus.It highlights certainaspects and elements,while

it neglectsothersand so leads to differentquestions.The threeapproach-

es are builton different epistemologicalfoundations.Adoptinga relativist

or relationalstandpoint,I decline to judge whichone of themwould be

more "correct,"as that would mean to a prioripreferone of them.

Instead,I suggestwe ask howthese perspectivescan be connected,keep-

ing in mind"how different framesof referenceare used to analyze the

'same' events,reflecting the differentpositionsof the actorsinvolvedin

the events themselvesand in their documentation"(Lewis & Mosse

2006:8). As in the case of development,the subjectitselfis constitutedby

the interpretations, definitions,and representations that are developed

byitsactors(Mosse2005). These representations changeaccordingto the

standpoint of the observer and they are shaped byeach one of them.So,

whatdo all theactors'representations have in commonand howcan their

perspectivesbe combined?

Let us observethe practiceof the actors in reverseorderas we trace

the actor-network PHED. The European researchercomes to investigate

the projectand the community. He participatesin and observesmeetings

and village life in Trraba. He interviewsand converseswiththose per-

sons who he believes to be keyactors,or moregenerally,who seem to

know more about the projectthan the average villager.Togetherwith

relatedobservations, theirstatementsare comparedto otherstudieswith

the aim of identifyingcontradictionsor similarities.Based on this

method,he formulatesgeneralizationsand statementsin the languageof

hisdiscipline.Atthe beginningofthejourney,hisaim is to studythe com-

796

This content downloaded from 200.123.187.130 on Thu, 27 Feb 2014 11:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CHRISTOPH

CAMPREGHER

munityand to transformthis experience into a scientifictext. Everycon-

tact he makes and every interview he undertakes changes his interestand

the outcome of his study. At the end of this process, his original interest

is associated with those of a series of actors, who influenced the course of

his investigation. It is transformedand translated (Calln and Law 1982).

The resulting text constitutes an actor-network in the sense that it inte-

grates the information,opinions, and perspectives of a series of persons.

It speaks in the name of and contains the voices of a larger set of actors.

Finally, the study is the end product of a chain of translation (Latour

1999), which produces a representation of what happens between a huge

number of persons and things in one part of the world, and introduces it

into the discourses at universities in differentplaces.

Indigenous village politicians are by themselves central elements of

differentchains. They need to establish relations with external institu-

tions in order to become relevant as representatives of the community.

They need to translate the multitude of persons and interests into a uni-

fied representation of the "indigenous community." Therefore they need

to use concepts and notions which are understood by external agents: The

villagers become the indigenous community.Their environment is trans-

lated into natural resources and these, in turn, will be associated with

other elements, such as the rightsstated in the ILO Convention 169. These

representations necessarily take the form of concepts that can be under-

stood and utilized by external institutionsand organizations. They need

to be understandable and compatible with the languages and discourses

of these institutionsin order to be recognized. Communication requires a

series of shared cultural representations, which allow actors to relate or

to integrate the differentinterests of, for example, indigenous peasants

and environmental NGOs.

Indigenous activistswho do not use this language and its concepts will

not be heard.8Theywill stay invisible elements of the assemblage that con-

stitutesthe communityand is represented by others. To be relevant in the

development arena implies the use of notions of its specificjargon (Escobar

1995), although they may representverydifferentvisions than those of the

powerful institutions.Being an indigenous representative then means to

talk about development, to be foror against the PHED, to protectthe envi-

ronmentand to representa very distinctculture. Only when a person suc-

ceeds in connecting elements from the economic, legal, social, cultural,

and ecological sphere utilizinga specific vocabulary, only then she or he

797

This content downloaded from 200.123.187.130 on Thu, 27 Feb 2014 11:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ShiftingPerspectiveson Development: An Actor-NetworkStudyof a Dam in Costa Rica

will be able to fulfilla representativefunction.These features,however,can

be interpretedas the resultof a specificnetworkingprocess in which indige-

nous leaders, supporters,and opponents mutuallyadapt to each other. In

other words, while indigenous representatives appear to be politically

engaged, critical of development, conservationist, independently of any

context, it is ratherbecause of the interactionswith a networkof external

actors that theyadopt and develop these features. In the same way,similar

features we attributeto indigenous cultures, peoples, or communities are

the product of networksthat cross boundaries between nations, between

the local and the global, or between thingsand humans.

The social scientists employed by the PHED mediate between the thou-

sands of people that are affected by the project directlyor indirectly,and

the few bureaucrats and engineers who design and plan it. They visit vil-

lages, speak to interested persons, and organize events and meetings

where they informpeople about the project. In their offices,they receive

the project plans and directivesas writtentexts,or in other words, as writ-

ten representationsof an envisioned future. Part of their work is to trans-

late these texts into a language understandable forthe population and to

sort out the elements that are most relevant forthe affected. At the same

time, they research the villages they visit. For project headquarters, they

need to transformtheir experiences again into written texts, much like

the independent anthropologist but under differentconditions. The real-

ity of the rural population needs to be transformed into writtenwords,

numbers, statistics, photographs, and maps. They become central ele-

ments in a chain that transformssocial realityinto useful informationthat

can be integrated into the project's plans and models.

In both directions, the informationthat flows along this chain is simul-

taneously reduced and amplified (Rottenburg2009). The executives of the

PHED cannot visit each village and each familyin the project area in order

to get a picture of the complex realityby themselves. They depend on the

representationsthat the project's employees produce in the formof state-

ments and statistics,necessary to combine it with informationfromother

relevant areas such as finances, geology or law, among others. Conversely,

the affected people cannot study every detail of the project's plans and

targets. The peasant family that worries about its home and its ground,

needs to know what the project signifiesforit. In both directions,the soci-

ologists and anthropologists reduce, select and amplify the information

that crosses their small offices,according to more or less stable criteria.

798

This content downloaded from 200.123.187.130 on Thu, 27 Feb 2014 11:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CHRISTOPH

CAMPREGHER

These development agents, in turn, depend on the work of mediators

such as the indigenous representatives. In their effortto establish a dom-

inant representation of what is going on, every one of them depends on

translatorswho speak in the name of the larger group of persons who live

there (Latour 1999). Otherwise, they would have to pass by every single

house to talk to every single household member. Some indigenous repre-

sentatives are recognized by them and enabled to speak for the group.

They become relevant if they are able to express concerns of the commu-

nity in relation to the project. Their words find a way into the

researchers' reportswhere they are re-represented.As they associate with

the project's agents or outside supporters, the indigenous leaders become

relevant and important to the project; simultaneously, the project starts

to form part of the community's concerns.

In the negotiation that precedes the construction of the dam, all of

these spokespersons struggle to establish representations that aim to

define the development of the dam. They intend to become obligatory

points of passage (Calln 1986) for the others in the network of human

and non-human allies. No indigenous activist can ignore the PHED if he or

she cares to be relevant as a spokesperson forthe community.Nor can the

PHED ignore the activists if it wants to establish a relation with the indige-

nous population. In the same way, the project needs to enroll an even

larger number of actors to become a stable actor-networkby itself: finan-

cial institutions,politicians, national and foreign firms,engineers, con-

structionworkers, among others. Their multitude of interests have to be

translated during this process of association and enrollment (Calln 1986),

and the independent researcher needs to write a text that assembles all

of them in order to conclude his research and to relate it to the discours-

es of his discipline.

IV. Conclusion

How much does the approach of this case study contribute to the devel-

opment of anthropology? By integratingthe anthropologist as the object

of analysis into our ethnographic field studies (what we might call the

STS turn), we highlight, first, the way he or she generates knowledge

while "circumstantially muddling through" (Marcus 2001:527) the field,

and second, how his or her cultural representations relate to those of

other actors. Drawing on concepts fromActor-NetworkTheory, I focused

799

This content downloaded from 200.123.187.130 on Thu, 27 Feb 2014 11:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ShiftingPerspectiveson Development: An Actor-NetworkStudyof a Dam in Costa Rica

on the relation between central actors in the case study, their discours-

es, and the main theoretical approaches in the anthropological study of

development. By foregrounding this relation in the text, I challenged

commonplace distinctions between scientific knowledge and the beliefs

or interpretations of the actors/informantsin the field. The result is a

multi-sitedethnography of development (Marcus 1995). One in which the

author starts to appear in the text, different(positioned) approaches are

combined, and we see how multiple actors construct the object of study

in the field. Combining and shiftingtheir differentperspectives avoids

one-sided accounts and allows us to provide a thicker description of

development in a local context.

Actors in a development arena which appear to have differentcultural

backgrounds- development agents, indigenous village politicians, and

the foreign researcher- do not necessarily act corresponding to different

cultural values. They do not belong to seperate "lifeworlds" (Arce and

Long 2000) or "worlds of knowledge" (Long 1989, Rossi 2006). Rather can

we show how these differentactor groups interact and how they mutual-

ly define each other's identities. Actor-NetworkTheory and the concept of

chains of translation not only avoid the establishment of apparently sep-

arated cultural spheres, they highlightthe processes in which actors trans-

formand translate differentand contraryinterestsin order to make them

compatible (Latour 1999).

The approaches of the three main groups in our case study have been

identified as elements in such chains of translations and I showed how

each one of them builds or even depends on the others in order to gath-

er, translate, and pass on information.As a consequence of their network-

ing activities (and even opposition or rejection implies the acknowledg-

ment and recognition of the other), all of them (development workers,

indigenous activists, and the researcher) increase their importance, no

matter if in the end the dam will be constructed, or not. Others (ordinary

community members, who engage less or only indirectlyin village poli-

tics) are re-represented by our main actors and their particular opinions,

considerations, and sorrows are translated into more general statements.

The studyof representationas proposed in this text may help to overcome

the resistance and adaptation/accomodation framework (Marcus 1995)

that has organized not only conventional research on indigenous peoples,

but also a considerable body of development studies (Escobar 1995,

Ferguson 1997b, Sachs 1992, Scott 1985).

800

This content downloaded from 200.123.187.130 on Thu, 27 Feb 2014 11:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CHRISTOPH

CAMPREGHER

While the chains of translation in STS usually appear to work well, in

the context of development they are controversial and contested. All our

actor groups have to strugglewith the riskthat the ones who follow in the

chain might question the representations they produce. These moments

become apparent when, for example, leading executives of the PHED

doubt that a small indigenous village could really stop their project, or

when they question the difficultyof findinga common representative or

committee that could speak for the community.

In indigenous Trraba, the community's differentfactions question the

legitimacy of their political speakers and thereby avoid the constitution

of a unified political representative body. Legal, economical, social, and

symbolical resources are mobilized in order to establish stable forms of

political representation. The study of representation as chains of transla-

tion as in the present case study may contribute to the ongoing debate on

indigeneity (Barnard 2006, Kuper 2003) and its political implications.

Finally,I hope to have shown that an empirical anthropology of represen-

tation which traces how concepts and their boundaries are produced and

translated by the very people we study and, at the same time, by our-

selves, is an important step towards a more symmetricalanthropology. It

expands what is in our ethnographic picture of the world by including the

fieldworkerand the research practice.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am gratefulto ChristianWawrinecand Michael Brendan Donegan for editing and

commentingon the text.Gabriele Habingerand PatriciaZuckerhutprovidedassistance

in the edition of an earlier Germandraftof this study.I am also gratefulto Elke Mader,

Georg Grnberg,and Andre Gingrichfor their help and advice. The research for the

case study was possible thanks to financial support from the Austrian Ministryof

Education and the Universityof Vienna. Last but not least, I want to thank the people

"in the field,"especially Digna and Enrique Riverain Trraba, as well as BorisGamboa,

JimmyGonzalez, and JorgeCole Villalobos of the PHED, who dedicated time, allowed

me to participatein theirmeetings,and shared their"perspectives" with me. Needless

to say,all errorsof fact and interpretationremain myown.

ENDNOTES

1Spanish: ProyectoHidroelctricoEl Diqus (PHED).

2Spanish: InstitutoCostarricensede Electricidad(ICE).

3The followingreport is a summaryof statements by members of the Departmentof

Social Investigation [rea Sodai) from a series of interviews undertaken between

801

This content downloaded from 200.123.187.130 on Thu, 27 Feb 2014 11:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

AnActor-

on Development:

Perspectives

Shifting Studyofa Dam inCostaRica

Network

Septemberand Novemberof 2006. It is not a quotation but a paraphrased summaryof

their statements about the relation between the PHED and Trraba. (Instituto

Costarricense de Electricidad. Members of the Social Department [Area Social]-

Conversationof 13.09.2006 in Buenos Aires.)

4Spanish:Asociacin de Desarrollo Integral(ADI).

5CostaRican Law 6172 of 1977.

6The Convention 169 (Convention on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples) of the

InternationalLabour Organisation(ILO) published in 1989 is the most importantlegal

referenceabout the rightsof indigenouspeoples at the internationallevel. It came into

force in 1991 after the ratificationby Norway and Mexico. Costa Rica signed the

Conventionin 1992. Accordingto Article7 of its constitution,internationalconven-

tions are superiorto national laws.

7lnCosta Rica, the Supreme Court"Saia IV" has supreme jurisdictionover constitution-

al cases. People can address the Sala IV when their fundamentalconstitutionalrights

are violated by legislativeor administrativemeasures. This legal action is called "recur-

"

so de amparo.

8Asshown bythe example of an older Teribewho stood up in a village assemblyin order

to tell the participantsthat god revealed to him that the dam would not be built ifcer-

tain religiouspracticeswere obeyed. The main part of the persons present,including

the members of human rightsNGOs, ignored the statement which obviously were

incompatiblewiththe discourse at work,although in another contextthe same state-

mentwould have been legitimate.The discussioncontinuedusingargumentsthat in our

(thatmeans the Occident's modern)understandingappear to be more "rational."

REFERENCES

Arce,Albertoand Norman Long,eds. 2000. Anthropology, Developmentand Modernity.

London: Routledge.

Artavia, Betania. 2008. "Despus de 38 aos de espera: Proyecto Hidroelctrico El

Diqus empezar en un ao." Diario Extra,February7, page 4.

Amador Matamoros,Jos-Luis.2002. "Identidad y polarizacin social en la comunidad

indgena de Curr, ante la posible construccinde una represa hidroelctrica."

M.Sc. Thesis. School of Anthropology,Universityof Costa Rica.

Barnard, Alan. 2006. "Kalahari Revisionism,Vienna and the 'Indigenous Peoples'

Debate." Social Anthropology 14(1):1-16.

Bierschenk,Thomas, Jean Pierre Chauveau, and Jean-PierreOlivier de Sardan, eds.

1999. Courtiersen development. Les villages africains en qute de projets. Paris:

Karthala.

Bloor, David. 1991 [1976]. Knowledgeand Social Imagery.Second edition with a new

foreword.Chicago: Chicago UniversityPress.

Caldern Gomez,JosA. 2003. "Desarrollo Hidroelctricoy Mecanismosde Interaccin

con Sociedades y TerritoriosIndgenas: el caso del P. H. Boruca en Costa Rica."

M.Sc. Thesis, School of Geography,Universityof Costa Rica.

Calln, Michel. 1986. "Some Elementsof a Sociology of Translation: Domesticationof

the Scallops and Fishermenof St. Brieuc Bay." In JohnLaw, ed. Power,Actionand

Belief:a New Sociologyof Knowledge?,196-233. London: Routledgeand Kegan Paul.

Calln, Micheland JohnLaw. 1982. "On Interestsand TheirTransformation:Enrolment

and Counter-Enrolment."Social Studies of Science 12(4):61 5-625.

802

This content downloaded from 200.123.187.130 on Thu, 27 Feb 2014 11:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CHRISTOPH

CAMPREGHER

Campregher,Christoph.2008. IndigenePolitikund Entwicklung.

Sozialanthropologische

Perspektiven.Saarbrcken: VDM.

Costa Rica. 1977. Indigenous Law of Costa Rica. Law Number6172 of 1977. San Jos,

Costa Rica.

Escobar, Arturo.1995. EncounteringDevelopment: The Making and Unmakingof the

ThirdWorld.Princeton: PrincetonUniversityPress.

Ferguson, James. 1997a. "Anthropologyand its Evil Twin: 'Development' in the

Constitutionof a Discipline." In Frederick Cooper and Randall Packard, eds.

InternationalDevelopmentand the Social Sciences. Essayson the Historyand Politics

of Knowledge,150-75. Berkeley:Universityof CaliforniaPress.

. 1997b [1990]. The Anti-PoliticsMachine: Development,De-Politicization

and Bureaucratic Power in Lesotho. 3rd Edition. Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press.

Gatschet, Albert S. 1894. "The Trraba Indians. Notes and News." American

Anthropologist, 7(2):218-219.

Geertz,Clifford.1973. "Thick Description:Toward an InterpretiveTheoryof Culture."

In Geertz, Clifford,ed. The Interpretationof Cultures:Selected Essays, 3-30. New

York: Basic Books.

Guevara, Marcos and Rubn Chacn. 1992. Territoriosindios en Costa Rica: orgenes,

situacin actual y perspectivas.San Jos,Costa Rica: Garca Hermanos.

Horrowitz,Michael. 1996. "On not Offendingthe Borrower.(Self?)-Ghettoizationof

Anthropologyat the WorldBank." DevelopmentAnthropologist 14(1):3-12.

Instituto Costarricense de Electricidad. 2006. El Proyecto Hidroelctrico Boruca.

Opciones Cajn y Veraguas.San Jos: ICE.

InternationalLabor Organisation.1989. ConventionNr. 169 "Conventionon Tribaland

IndigenousPeoples." Adopted on June 27, 1989 by the General Conferenceof the

International Labour Organisation at its seventy-sixthsession. Entryinto force

September 5, 1991. Geneva.

Kuper,Adam. 2003. "The Returnof the Native." CurrentAnthropology 44(3): 389-95.

Latour,Bruno. 1987. Science in Action: How to Follow Scientistsand EngineersThrough

Society.MiltonKeynes: Open UniversityPress.

. 1993. We Have NeverBeen Modern.Cambridge,MA: HarvardUniversity

Press.

. 1994. "On Technical Mediation: Philosophy, Sociology, Genealogy."

CommonKnowledge3(2): 29-64.

. 1999. Pandora's Hope: An Essay on the Reality of Science Studies.

Cambridge,MA: HarvardUniversityPress.

. 2005. Reassemblingthe Social. An Introductionto Actor-Network

Theory.

Oxford:OxfordUniversityPress.

Lewis, David and David Mosse, eds. 2006. DevelopmentBrokersand Translators.The

Ethnography of Aid and Agencies.Bloomfield,CT: Kumarian Press.

Long, Norman, ed. 1989. Encounters at the Interface: a Perspective on Social

Discontinuitiesin Rural Development.Wageningen:AgriculturalUniversity.

Marcus,George. 1995. "Ethnographyin/ofthe WorldSystem:The Emergenceof Multi-

sited Ethnography."Annual Reviewof Anthropology 24:95-117

. 2001. "From Rapport Under Erasure to Theaters of Complicit

Reflexivity."QualitativeInquiry7(4): 519-528.

803

This content downloaded from 200.123.187.130 on Thu, 27 Feb 2014 11:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Perspectives

Shifting AnActor-

on Development: Studyofa Dam in CostaRica

Network

Mosse, David. 2005. CultivatingDevelopment: An Ethnographyof Aid, Policy and

Practice. London: Pluto Press.

Olivier de Sardan, Jean-Pierre.2005. Anthropologyand Development: Understanding

Contemporary Social Change. London and New York: Zed Books.

Rossi, Benedetta. 2006. Aid Policies and RecipientStrategiesin Niger:WhyDoors and

Recipients Should Not Be Compartmentalized into Seperate 'Worlds of

Knowledge.'" In David Lewis and David Mosse, eds. Development Brokers and

Translators:The Ethnography of Aid and Agencies,27-50. Bloomfield,CT: Kumarian

Press.

Rottenburg,Richard. 1998. "Towards an Ethnographyof Translocal Processes and

Central Institutionsof Modern Societies." In Aleksander Posern-Zielinski,The Task

of Ethnology. Cultural Anthropology in Unifying Europe, 59-66. Pozna:

WydawnictwoDrawa.

. 2009. Far-FetchedFacts. A Parable of DevelopmentAid. Cambridge,

Mass.: MIT Press.

Sachs, Wolfgang.1992. The DevelopmentDictionary:A Guide to Knowledgeand Power.

London and New Jersey:Zed Books.

Said, Edward. 1978. Orientalism.London: Routledge.

Schulz-Schaeffer, Ingo. 2000. "Akteur-Netzwerk-Theorie.Zur Koevolution von

Gesellschaft,Natur und Technik." In JohannesWeyer.Soziale Netzwerke.Konzepte

und Methodender sozialwissenschaftlichenMethodenforschung, 189-211. Mnchen:

Oldenbourg.

Scott,James. 1985. Weaponsof the Weak: EveryDay Formsof Peasant Resistance.New

Haven: Yale UniversityPress.

von Organisationen

Weilenmann,Markus.2005. "Ist Projektrechtein Erfllungsgehilfe

der Entwicklungshilfe?Eine Fallstudie aus Burundi." Entwicklungsethnologie

14(1-2):129-148.

804

This content downloaded from 200.123.187.130 on Thu, 27 Feb 2014 11:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Checking If The Site Connection Is SecureDocument1 pageChecking If The Site Connection Is SecureFacundoPMNo ratings yet

- Edgeworth - Acts of Discovery - An Ethnography of Archaeological PracticeDocument73 pagesEdgeworth - Acts of Discovery - An Ethnography of Archaeological PracticeFacundoPMNo ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument14 pages1 PBFacundoPMNo ratings yet

- Stillitoe PaulDocument20 pagesStillitoe PaulFacundoPMNo ratings yet

- Dufraisse - Interpretation of Firewood Management As A Socio-Ecological IndicatorDocument2 pagesDufraisse - Interpretation of Firewood Management As A Socio-Ecological IndicatorFacundoPMNo ratings yet

- Adan Quan Clase 2Document19 pagesAdan Quan Clase 2FacundoPMNo ratings yet

- Bennett y Rogers - Street Music, Technology and The UrbanDocument13 pagesBennett y Rogers - Street Music, Technology and The UrbanFacundoPMNo ratings yet

- Burocracy and Indigenous KnowledgeDocument18 pagesBurocracy and Indigenous KnowledgeFranciscoNo ratings yet

- Mosse Anti-Social AnthropologyDocument23 pagesMosse Anti-Social AnthropologyFacundoPMNo ratings yet

- Colin LeysDocument17 pagesColin LeysFacundoPMNo ratings yet

- 21A.360J / Sts.065J / Cms.710J The Anthropology of Sound: Mit OpencoursewareDocument16 pages21A.360J / Sts.065J / Cms.710J The Anthropology of Sound: Mit OpencoursewareFacundoPMNo ratings yet

- The Soundscape NewsletterDocument13 pagesThe Soundscape NewsletterFacundoPMNo ratings yet

- The Political Economy of MusicDocument190 pagesThe Political Economy of MusicMitia Ganade D'Acol100% (2)

- Sound and Sentiment, 30th Anniversary Edition, by Steven FeldDocument38 pagesSound and Sentiment, 30th Anniversary Edition, by Steven FeldDuke University PressNo ratings yet

- 21A.360J / Sts.065J / Cms.710J The Anthropology of Sound: Mit OpencoursewareDocument16 pages21A.360J / Sts.065J / Cms.710J The Anthropology of Sound: Mit OpencoursewareFacundoPMNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- HouseDocument19 pagesHouseSandy100% (2)

- Wierzbicka PrimitivesDocument3 pagesWierzbicka PrimitivesMint NpwNo ratings yet

- Understanding Consumer and Business Buyer BehaviorDocument50 pagesUnderstanding Consumer and Business Buyer BehavioranonlukeNo ratings yet

- Lesson 9 - The Spiritual SelfDocument1 pageLesson 9 - The Spiritual SelfmichelleNo ratings yet

- Developmental Pathways To Antisocial BehaviorDocument26 pagesDevelopmental Pathways To Antisocial Behaviorchibiheart100% (1)

- A Study On Farmer Buying Behaviour For RotavatorDocument47 pagesA Study On Farmer Buying Behaviour For Rotavatorvishvak100% (1)

- BURKITT, Ian - The Time and Space of Everyday LifeDocument18 pagesBURKITT, Ian - The Time and Space of Everyday LifeJúlia ArantesNo ratings yet

- Strategic & Operational Plan - Hawk ElectronicsDocument20 pagesStrategic & Operational Plan - Hawk ElectronicsDevansh Rai100% (1)

- SampsonDocument9 pagesSampsonLemon BarfNo ratings yet

- Communicative Musicality - A Cornerstone For Music Therapy - Nordic Journal of Music TherapyDocument4 pagesCommunicative Musicality - A Cornerstone For Music Therapy - Nordic Journal of Music TherapymakilitaNo ratings yet

- Cory Grinton and Keely Crow Eagle Lesson Plan TemplateDocument5 pagesCory Grinton and Keely Crow Eagle Lesson Plan Templateapi-572580540No ratings yet

- Horror Film Essay Assessment StrategyDocument3 pagesHorror Film Essay Assessment StrategyAndreea IepureNo ratings yet

- Marketing Yourself Handout (1) : Planning Phase Situation AnalysisDocument6 pagesMarketing Yourself Handout (1) : Planning Phase Situation AnalysisSatya Ashok KumarNo ratings yet

- Contemporary WorldDocument1 pageContemporary WorldAngel SantiagoNo ratings yet

- Hospital Mission Vision Values ExamplesDocument4 pagesHospital Mission Vision Values ExamplesNesyraAngelaMedalladaVenesa100% (1)

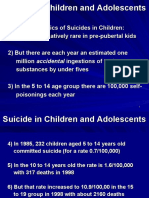

- Suicide in Children and Adolescents: AccidentalDocument32 pagesSuicide in Children and Adolescents: AccidentalThambi RaaviNo ratings yet

- Segmentation of Shoppers Using Their Behaviour: A Research Report ONDocument68 pagesSegmentation of Shoppers Using Their Behaviour: A Research Report ONpankaj_20082002No ratings yet

- W Astin Implement The Strategies and Rubric - Module 4Document6 pagesW Astin Implement The Strategies and Rubric - Module 4api-325932544No ratings yet

- Your Honor, We Would Like To Have This Psychological Assessment Marked As P-10Document7 pagesYour Honor, We Would Like To Have This Psychological Assessment Marked As P-10Claudine ArrabisNo ratings yet

- Sternberg Press - October 2017Document6 pagesSternberg Press - October 2017ArtdataNo ratings yet

- Social Media MarketingDocument11 pagesSocial Media MarketingHarshadNo ratings yet

- Biopsychology 1.1 1.4Document12 pagesBiopsychology 1.1 1.4sara3mitrovicNo ratings yet

- K-1 Teacher Led Key Ideas and DetailsDocument2 pagesK-1 Teacher Led Key Ideas and DetailsJessica FaroNo ratings yet

- OB Robbins Chapter 2Document21 pagesOB Robbins Chapter 2Tawfeeq HasanNo ratings yet

- Annotated Bibliography 1Document7 pagesAnnotated Bibliography 1api-355663066No ratings yet

- The Nature of Multi-Grade ClassesDocument2 pagesThe Nature of Multi-Grade ClassesApril Christy Mae Torres - CaburnayNo ratings yet

- GHWA-a Universal Truth Report PDFDocument104 pagesGHWA-a Universal Truth Report PDFThancho LinnNo ratings yet

- Talent AcquistionDocument14 pagesTalent AcquistionrupalNo ratings yet

- 3communication EthicsDocument12 pages3communication EthicsEmmanuel BoNo ratings yet

- Questions 1-4 Choose The Correct Letters A, B or CDocument6 pagesQuestions 1-4 Choose The Correct Letters A, B or CshadyNo ratings yet