Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Eating-Disordered Patients With Without Self-Injurious Behaviors - A Comparison of Psychopathological Features

Uploaded by

Alicia Svetlana0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

26 views19 pagesWWW

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentWWW

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

26 views19 pagesEating-Disordered Patients With Without Self-Injurious Behaviors - A Comparison of Psychopathological Features

Uploaded by

Alicia SvetlanaWWW

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 19

European Eating Disorders Review

Er. Eat Disonders Ree. 1, 379-36 (2008)

abiched online 9 Apel 2003 n We InterScience (www.tercenes. wiley com). BOK 10002/n1510,

Paper

Eating-disordered Patients With and Without

Self-injurious Behaviours: A Comparison of

Psychopathological Features

Laurence Claes*, Walter Vandereycken and Hans Vertommen

Department of Psychology, Catholic University of Leuven, Leuven,

Belgium

Objective: A considerable numer of eating-disordered patients also display

all kinds of self-injurious behaviours (SIB), which might be viewed as an

indicator of psychopathological severity

Method: To test this hypothesis in 70 females admitted to a specialized

treatment programme for eating disorders, a wide spectrum of psychopatho-

logical features toas studied by means of self-reporting questionnaires: clinical

symptomatology, personality disorders, aggression regulation, trauma history,

dissociation and body experience. A comparison was made between patients

with (n= 27) and without SIB (n= 43), as well as between patients with one

(n=13) versus more types (n= 14) of SIB.

Results: In general, patients with STB reported significantly more complaints

or signs of anxiety, depression, hostility, cluster B personality disorders,

feelings of anger, traumatic experiences, dissociation and negative appreciation

of body size. The presence of more than one type of SIB cus linked to a more

pronounced clinical symptomatology and trauma history. Copyright © 2003

John Wiley & Sons, Ltd and Eating Disorders Association.

INTRODUCTION

Like other authors (e.g. Herpertz, 1995) we use the term self-injurious

behaviour (SIB) for moderate derangements of the body surface, such as

cutting, carving and buming of the skin, Such SIB is defined as a direct,

socially unacceptable behaviour that causes minor to moderate physical

injury, while the individual is in a psychologically distressed state but is,

Correspondence to: Laurence Claes, Catholle University Leuven, Department of Peychology,

“Tieneestrant 102, 3000 Leven, Belgiam. Tel 3216-8261 53, Foe + 82-16-32 5916

"Buropean ating Disorder Reo

Coprsghe © Ja Wey Sone, Ll aed Eng Detar Asscttn. 5) 379-596 0015)

aes etal, Eur. Eat. Disorders Rev. 11, 379-996 (2003)

not attempting suicide nor responding to a need for self-stimulation or a

stereotyped behaviour (as found in mental redardation or autism). In a

considerable frequency SIB has been described in eating-disordered

patients (e.g. Favara & Santonastaso, 1998, 2000) for whom it may have

many different meanings or functions (Suyemoto, 1998). Those

anorectics and bulimics who admitted SIB reported higher levels of

general psychopathological dysfunctioning (Claes, Vandereycken, &

Vertommen, 2001; Favaro & Santonastaso, 1999). Hence, from a lini

‘viewpoint it is relevant to assume that the presence of SIB could be an

indicator of the severity of the psychopathology, as suggested by,

Newton, Freeman, and Munro (1993), To test this hypothesis, we have

assessed clinical symptomatology, personality disorders, trauma his-

ory, dissociation, body experience and aggression regulation in a

clinical sample of eating-disordered patients with and without a history

of self-injury. Because of the wide variety in forms and frequency of SIB

a differentiation within this subgroup is warranted, We did not choose

the option of comparing ‘compulsive’ SIB (eg. scratching, nail biting)

with ‘impulsive’ SIB (e.g. burning, cutting), as proposed by Favaro and

Santonastaso (1998), because of the questionable distinction and the fact

that a previous study showed that many patients displayed both types

of SIB (Claes et al., 2001). Therefore we decided to split the group

according to a clear-cut criterion: the number of reported SIBs.

With respect to those patient characteristics thought to be worthy of

study, we were inspired by the following findings or questions. With

respect to clinical symptomatology, research in other patient samples

showed a relation between SIB and antisocial behaviour (e.g. Simeon

etal, 1992), increased number of physical illnesses and complaints (e.g.

Herpertz, 1995), current sexual dysfunction (e.g, Dulit et al., 1994), and

sexual behaviour at high risk for HIV (Diclemente, Ponton, & Hartley,

1991). The finding that SIB is linked to anger and anxiety (e.g. Simeon

et al., 1992) has not been confirmed by other researchers (eg, Dulit et al.,

1994; Herpertz, 1995). An association with depressive symptomatology

is also controversial (e.g. Herpertz, 1995). Although SIB is clearly

differentiated from suicide, self-injurers tend to report more suicidal

ideation and past suicide attempts independent of their SIB (e.g. Dulit

et al,, 1994); this is especially true for those with a borderline personality

disorder (Herpertz, 1995). Of all personality disorders the latter is most

often associated with SIB (e.g. Langbehn & Pfohl, 1993). Although this

association may induce a diagnostic bias (Ghaziuddin, Tsai, Naylor, &

Ghaziuddin, 1992), SIB may be viewed asa marker for severe personality

disorder (Simeon et al., 1992). With respect to traumatic experiences and

related problems, research has supported an association with SIB: at

least half of these patients experience depersonalization and a sense of

Copyright 208 Jahn Wiley & Sons id and Eating Disorders Associaton, 380

Eur, Eat, Disorders Rev. 11, 379-296 (2008) Self-njurious Behaviours

analgesia during the act (Leibenluft, Gardner, & Cowdry, 1987).

Furthermore, selfinjurers are more likely to come from families

characterized by divorce, neglect, or emotional deprivation (e.g. Pattison,

& Kahan, 1983), and often report a history of physical or sexual abuse i

childhood (eg. Langbehn & Pfohl, 1993). Last but not least, selft

destructiveness and interpersonal violence are two types of aggression.

Self-destructiveness is the deliberate attempt to inflict physical harm on

oneself and interpersonal violence is the deliberate attempt to cause

serious physical injury to other. In spite of the need for studies on the

coexistence of these behaviours, the relationship between self-destruc-

tiveness and interpersonal violence has received little scientific attention

(Hillbrand, 1995),

METHOD.

Subjects

We have gathered data from 70 female inpatients (mean age=21.7 years,

‘SD =6.2 years) admitted to a specialized unit for the treatment of eating

disorders. By means of a clinical interview supplemented by the Eating

Disorder Evaluation Scale (EDES; Vandereycken, 1993) patients were

diagnosed according to DSM-IV criteria (American Psychiatric Associa~

tion, 1994): 32.9 per cent (n= 23) as anorexia nervosa restrictive subtype

(AN-R), 25,7 per cent (i= 18) as anorexia nervosa bingeing-purging,

subtype (AN-P), and 41.4 per cent (n= 29) as bulimia nervosa (BN).

Instruments

The following set of self-report instruments was used to assess SIB,

clinical symptomatology, personality disorders, trauma history and

related problems, and aggression regulation, Questionnaires were

completed at admission as a part of the routine assessment.

Self-Injury Questionnaire

To assess SIB we made use of a newly developed self-reporting

instrument, the Self-Injury Questionnaire (SIQ; Claes et al., 2001; see also

Vanderlinden & Vandereycken, 1997), Subjects are asked if they have

deliberately injured themselves in the past year (hair pulling, scratching,

bruising, cutting, burning); if so, they are to specify —for each behaviour

separately—how often this happened, if they felt some pain, and what

kind of emotional experiences they had at the moment of self-injury

(being nervous, bored, angry, sad, scared, or some other feeling).

Additionally, they were asked to give some information about the age of

(Copyright © 2005 abn Wiley Song, id and Eating Dioner Assocation. 381

Eur. Eat. Disorders Rev. 11, 379-896 (2008)

injury, the first time such behaviour occurred

(calculated from the moment of admission: e.g. in the last 6 months,

between 6 and 12 months earlier), the body parts that were injured (e.g.

arms and /or hands, legs and /or feet) and, finally, how the self-injurious

act was considered (e.g. as an uncontrollable act or as a planned act).

Symptom Checklist

The Symptom Checklist (SCL-90; Dutch version: Arrindell & Ettema,

1986) is a well-known measure for the assessment of a wide array of

psychiatric symptoms. Along with a global measure for psychoncuroti-

cism, it measures complaints of (general/phobic) anxiety, depression,

somatization, obsessions /compulsions, paranoid ideation and inter-

personal sensitivity, hostility, and sleeplessness.

Munich Alcohol Test

The Munich Alcohol Test (MALT; Dutch version: Walburg & van Limbeek,

1985) was administered to assess several aspects of alcohol abuse such

as the admission of alcohol abuse, withdrawal symptoms, and

psychological as well as social problems due to the abuse.

Suicidal Ideation Scale

The 10-item Suicidal Ideation Scale of Rudd (1989) was added to assess

suicide risk.

ADP-IV questionnaire

Aimed at assessing personality disorders, the Dutch ADP-IV ques-

tionnaire (Schotie, De Doncker, Vankerckhoven, Vertommen, & Cosyns,

1998) consists of 94 items, which represent the 80 criteria of the 10 DSM-

IV personality disorders in a randomized order. The ADP-IV produces a

dimensional trait score and a categorical personality diagnosis. The

dimensional trait scores (which will be used in this study) are computed

by adding the item scores for each of the personality disorders

separately, for the three clusters of personality disorders (Cluster A:

Paranoid, Schizoid, Schizotypal; Cluster B: Antisocial, Borderline,

Histrionic, Narcissistic; Cluster C: Avoidant, Dependent, Obsessive-

Compulsive) and for a total trait score

Leiden Impulsiveness Scale

‘The Leiden Impulsiveness Scale (State/Trait) (LIS; developed by R. J.

Verkes) comprises 25 items: 11 items, supposed to measure impulsive-

ness conceived asa trait, were selected out of the Eysenck Impulsiveness

‘Scale (I; Eysenck, Pearson, Easting, & Allsopp, 1985); 14 items focus on

impulsiveness as a state and ask which of several impulsive behaviours

‘Copyright © 2008 ohn Wily Sons, Le and Eatog Disondens Aeration, 382

Eur, Eat. Disorders Reo. 11, 379-396 (2003) Selfinjurious Behaviow:s

were shown during the last week. The behaviours of interest are for

example gambling, drinking too much alcohol, fighting, bingeing, and

self-injuring (in our data analysis, the latter has been left out of course, to

‘measure impulsiveness in patients with SIB).

‘Traumatic Experiences Questionnaire

‘The Traumatic Experiences Questionnaire (TEQ; Nijenhuis, van der Hart, &

Vanderlinden, 1995) lists several kinds of emotional neglect and abuse,

physical abuse, sexual abuse (by family members and others), serious

family problems (such as alcohol abuse, poverty, psychiatric problems

of a family member), decease or loss of a family member, bodily harm,

and war experiences. For 28 items the subject is asked to indicate

whether he or she has had this kind of experience

Dissociation Questionnaire

‘The Dissociation Questionnaire (DIS-Q; Vanderlinden, Van Dyck,

Vandereycken, Vertommen, & Verkes, 1993) aims at assessing dissocia-

tive experiences: identity confusion and fragmentation (referring to

experiences of depersonalization and derealization), loss of control (over

behaviour, thoughts and emotions), amnesia (memory lacunas), and

absorption

Body Attitude Test

The Body Attitude Test (BAT; Probst, Vandereycken, Van Coppenolle, &

Vanderlinden, 1995) consists of 20 items to be scored on a 6-point scale

from ‘always’ (score=5) to ‘never’ (score=0). The higher the score, the

more abnormal the body experience. Meaningful subscales are: negative

appreciation of body size, lack of familiarity with respondent's own

body, and general body dissatisfaction.

StateTrait Anger Scale

The State-Trait Anger Scale (STAS; Spielberger, Krasner, & Solomon,

1988) includes separate scales measuring two different notions of anger.

State~Anger is defined as an emotional state consisting of subjective

feelings of tension, annoyance, irritation, fury and rage. The State-

Anger seale includes 10 items to be rated on a 4-point Likert scale, where

the respondents answer how they feel at a specific moment. Trait-Anger

is defined in terms of individual differences among, people in their

disposition to perceive a wide range of situations as annoying or

frustrating and in their tendency to respond to such situations with

marked elevations in State-Anger. The Trait-Anger scale also includes

10 items to be rated on a 4-point Likert scale but here the respondents

answer how they feel in general.

‘Copyright 200 Joke Wiley & Son Lid ud Eating Disorders Asoc, 383

L. Claes etal ur. Fat. Disorders Rev. 11, 579-396 (2003)

Anger Expression Seale

The Anger Expression Scale (AX; Spielberger et al., 1988) is designed to

judge how people usually react when they feel angry or furious. The

scale consists of 24 items, to be rated on a 4-point Likert scale. Two

subscales (each of eight items) discriminate between individual

differences in the tendency to express anger against other people or

objects in the environment (AX/Out) and experiences or feelings of

anger which are suppressed (AX/In). The third subscale (eight items)

refers to control over feelings of anger and is named AX/Control

Aggression Questionnaire

The Aggression Questionnaire (AQ; Buss & Perry, 1992) represents an

updated and psychometrically improved version of the Buss-Durkee

Hostility Inventory (Buss & Durkee, 1957). The final questionnaire

consists of 29 items measuring four concepts: physical aggression,

verbal aggression, anger, and hostility.

Hostility and Direction of Hostility Questionnaire

‘The Hostility and Direction of Hostility Questionnaire (HDHQ; Caine,

Foulds, & Hope, 1967) was designed to sample a wide, though not

exhaustive, range of possible manifestations of aggression, hostility or

punitiveness. It consists of 51 items and comprises five subscales: Urge

to Act Out Hostility (AH), Criticism of Others (CO), Projected

Delusional or Paranoid Hostility (PH), Self-Criticism (GQ, and Delu-

sional Guilt (DG). The first three subscales are summed to form an

extrapunitive (blaming others) score, and the latter two added to yield

an intropunitive (inwardly directed hostility) score. Furthermore, a

Direction of Hostility score (DH) score may be obtained from a formula

in which the sum of the three extrapunitive scales (AH +CO-+PH) is

balanced by subtracting it from the sum of twice the SC score and the

DG score: Direction of Hostility (DH) = (2SC + DG) - (AH + CO + PH).

Positive scores thus indicate intropunitiveness, while scores in a

negative direction indicate extrapunitiveness.

Data analysis

To find out whether the proportions of a particular self-injurious act

among the different ED subgroups are equal or not, we made use of the

likelihood-ratio chi-square statistic (L?; Mood, Graybill, & Boes, 1974).

‘This statistic tested the model with equal proportions among the groups

against the model with different proportions among the groups. When

the value of L? under the x” distribution proves to be significant, one can

reject the null hypothesis that the proportions among the different

‘groups are equal. Differences among the ED patients with and without

Copyright © 208 John Wy & Song, Land Rating Dieters Ascton 34

Eur. Eat, Disorders Rev. 11, 379-396 (2003) Self-injurious Behaviours

SIB with respect to the interval scaled variables were calculated by

means of ANOVAs. Post oc comparisons were made by means of

Scheffé’s post-hoc tests as provided by SPSS (version 10).

RESUI

TS

Table 1 shows the frequency of the different types of SIB in the three ED

subgroups. A total of 27 patients (38.6 per cent)—including six AN-R,

five AN-P and 16 BN—admitted to having carried out at least one form

of SIB. Nine patients (12.9 per cent) reported hair pulling, 10 scratching.

(14.3 per cen), five bruising (7.1 per cent), 22 cutting (31.4 per cent) and

eight burning (114 per cent). The differences between the two (hair

pulling, bruising) or three (scratching, cutting, burning) diagnostic

subgroups for each of these self-injurious acts were not significant (hair

pulling: L?=2.27, di 0.13; scratching: L?= 1.70, df=2, p=0.43;

bruising: L? = 0.04, df= 1, p=0.84; cutting: L?=2.46, df=2, p=0.29;

burning: [= 4.23, df=2, p= 0.12)

‘About half of the 27 self-injurious patients (n= 13) reported only one

form of SIB, while the others admitted two or more. At the time of

admission, 11.1 per cent (=3) of the patients had injured themselves

less than a month ago, 22.2 per cent (1 =6) between 1 and 12 months

ccarlier, 29.6 per cent (n =8) between 1 and 5 years previously, and 37 per

cent (nt =10) more than 5 years ago. Parts of the body that were mostly

injured were arms and hands (n= 19; 704 per cent), head and neck

(1=5; 18.5 per cent), legs and feet (= 1, 37 per cent), trunk and belly

(n=1, 3,7 per cent), and genitals (x= 1, 3.7 per cent). Only one patient

reported that her SIB was planned, whereas the others considered the

self-injurious acts as uncontrollable and /or unexpected.

Comparing the eating- dee TOD Ae 00> My

00:

W608 wee “Ost cop ste wo 9 = wo ow

ou sw " eo 99 won 06 on oF

SBP wZEL vue |) tise) cae) cH

“uy su st wo £6 o) rm fe) es

ou sh i @9 set 6) et =) oe

87% 508 cay @m — ¥8s GO 979 = GaN eae

n8vs su ve Go sa ap ste see

ll su ost Wo ate GO 6 8) e&

“OLS acs vis @m 909 69 09 62 ete

OEE aeetET ver wo cor © 2% 9) OT

saS'6r vs 9c. co vee ©) re FEE

as) Ww as w as) ow as Ww

oon aa a a"

sae SAE) @) 918 ON 0) AIS [IOL, (@ ais t< @ast

WHT Is POW ars IM

Teer,

sis

Aowopagnsuy

uogeziyewos

sworssaadoq]

eigoud

Spavay

06-198

AIS OWI pue ypEM sjuaHed paropsosyp-Suped 20} (SIs) aT uoHEapT }ePPMS,

2un Bue (L-TYFY) 1894, [OMOOTY WHERYA ay “O6-1DS AMP UO (SuONETAAP prepueys) Sazods uraus ay) Jo WosTedwMO “z aTqeL,

387

‘Copyright © 2608 John Wy & Sons, Lad and Eating Disorder Aseiaton

g ou so ost {9} Oet (99) TST

id su 60e Lie re oe ‘dutoo-sqQ,

g su su cd Tre ose ele quapuadaq,

AL OS o 7 oot a eo

S| su su vet 987 ed ed SRIOLETH

i) os 7 = es eee

= vu 96'S cee Le 98h oeb ouTepIog,

a or ee ste Tse Wee redijoznps,

oe 7 es as ogee

a

aor wee eon epee wescon ea

oe oust

) AIS ON ) IS TOL

: srr aus

j a

a

ATs moypEO PUE

Apia stuaned pozoprosyp-Sue9 10y S11 pue ATE 2p Ho (SuoHE}A9p prepurs) Sar09s Meausayp Jo WosHEAUTOD “€ a1aPL

‘Coprigit © 2000 ohn Wiley Sons Li and Eating Disorders Asoston

Self-injurious Behaviours

Eur, Eat, Disorders Rev. 11, 379-396 (2008)

1000> doe !100> Ao 00> dy

su Lo can ors em ce woo 199 He) ose en

ou ‘su ey st co ver OP) TH DOL onnespessig

su su Go os «eo siz «9 se © cor Avserrareg

ou WTS 6D ost (con siz @e) se OD Fat ears pou

AVI

su gett ©) eoeL OH THT Lust) voST ree

su ou eo rst © 69r «Ps 6) ea vwordiosay,

su ate eL ©) eet em te en Le 6D 9s esoumy

su wageZ con ror won az TM) ses Hey omo Jo S807

su wager uD rss ww OD 818 GE—_¥99_woRsRIUOD Aap

Osta

MP6TL—o9LR 6 we oe uo 066 oo sr 24005 10,

ntEIZ nT 0 ero 180 0) 1 wo 0€0 asnge jenxes,

ETL eB 9E wo 120 1 (90) és (0) 690 uonepramnut x25

eu EL @o 9x0 “0 160) 001 CO 0 aenge peorshiy

se 06F © 10 Eat oD eet ott asngy 304g,

su ‘su @p #80 180 oD HT Go 90 vpa(8oN our

Oa.

a Ww as) Ww as ow as) Ww

een eu nou ="

se) (PSE) (©) a5 ON ©) as ek @ ais t< ais t

word as MOE, as WM

IS mmowpes Pur wpe

suaned paraprostp-Bune9 10) LV PUe DSIC DAL 2M Uo (SuoHEIAap prepUuE}s) sa10>8 UeaLE a4p Jo UostredLIO} “} >14eL

389

Copyright 2008 John Wey & Son, Led ane Hating Dieter asus,

Bl ee ~~ GD ve) Do Ze Dc» gfagnsoy jo mo Busy

S) osu aise wD se 6D os ow (0 —-¥S_~—_Ausoy jo sno Bunow

a) 5 0 oy et gD eae ou cet

Feet eMac cE Caen gee ou |) HHL

s| oo ep coe eM ve ce een see

eS) su eH) se ex 9) oe

g| GD at Dat oot Pca

es) ™ oo Gh mz 69 oF se “oe

: Sn co) 0

vu yu est vor ens) Bt

BZ) osu su 661 ew rm) coe

<| 8) US) gE) om as) st esuop ay

a x

su eee sit re rat ret aes

su we) THLE). HL ee aL

sys

a Ww a Ww a W a WwW

— a wae a

se) (PEE) US ON ©) as ToL, (@ as t< aust

IS OHM a1 EM

L. Claes etal

araprostp-Gupeo 30) [HGH pue DVddl “XV ‘SVLS 2tn wo

IS mom pue pe syOHd

yelaap prepueys) saxoos uvat aup jo uostreduto °s a1qUJ,

Copyight © 2003 ohn Wiiky Sons, Ll and Eating Disorders Associaton,

Self-njurious Behaviours

&

g

= 1509 uae wa a Susp

: 00> dy 1150 >in 5004s

lec 9 ue 19 Jonson

§[ su su 9 G9) ec rs ‘sor ner

Hon ow se DOs Dt Ts mp

su Lore s 03 18 @D o6 & soaks

Bose ace ro) eek sa salud

ou uw It wD 6T on ee $T Avmnsoy payafory

Bl ors atey 2 Gc @d os v9 sao 0 ws

391

{Copyright © 200 John Way & Sons, Land Rating DiscrersAssseton

L. Claes etal Eur. Bat. Disorders Rev.

179-396 (200)

anger-out and anger-control reactions. Furthermore, patients with SIB

did not display more verbal or physical aggression on the BPAV than

patients without SIB. On the contrary, on the acting-out hostility scale of

the BDHI, patients with SB showed higher scores. However, if we

climinate the item in this scale which refers to SIB, this statistical

significance disappears. Therefore, we can conclude that patients with

SIB experienced more angry feclings, but did not show more direct

(physical, verbal) aggressive behaviours against others or things. With

respect to hostility, described by Buss and Perry (1992) as the cognitive

component of aggression, the groups were not differentiated from each

other. However, patients with SIB showed much more self-criticism and

guilt, and were thus more intropunitive than patients without SIB. A

comparison of patients with one versus more types of SIB did not reveal

significant differences with respect to anger, hostility and (verbal/

physical) aggressive behaviours against others. The subgroups only

differed with respect to anger-control, which was higher in patients with

more types of SIB. One should keep in mind here that this concerns

control of angry reactions against others but not necessarily against

themselves.

DISCUSSION

‘The present study shows the frequency of self-injury in different

subtypes of ED patients. Thirty-eight per cent of the total group reported

atleast one form of SIB: in AN-R 26.1 per cent, in AN-P 27.8 per cent, and

in BN 55.2 per cent. These results are in line with other research findings.

Jacobs and Isaacs (1986) noted that 35 per cent of AN patients show SIBs,

and Mitchell et al. (1986) reported SIB in 40.5 per cent of BN patients.

Furthermore, in accord with several other authors (eg. Favaro &

Santonastaso, 2000; Welch & Fairburn, 1996), our results do not show

any significant differences in SIB frequencies among the AN and BN

subgroups. In contrast to other authors (e.g. Favaro & Santonastaso,

2000), who show that impulsive SIB such’as skin cutting is more

frequent in AN-P than in the AN-R, we did not find any significant

difference between the AN-R and the AN-P group.

Eating-disordered patients with SIB show more clinical symptoma-

tology—anxiety, depression, and hostility—than patients without SIB.

Furthermore, within the SIB group, the highest scores on clinical

symptomatology were found among those patients who carried out

more than one type of SIB. Therefore, we may conclude that the number

of SIBs can be considered an index for the severity of clinical

symptomatology. This finding is also confirmed by the fact that patients

Copyright 200 Joh Wey & Sons 1 and Eating Disorder Asin, 392

Eur, Bat, Disorders Rev. 11, 379-396 (2003) Selfinjurious Behaviours

with STB report more suicidal ideation than those without SIB. This was

also noted by Hillbrand (1995): ‘In spite of the differences between SIB

and suicidal behaviour, these two forms of aggression against sclf

coexist frequently. Suicidal behaviour has been estimated to occur in 50

per cent to 90 per cent of self-injurious individuals’.

Furthermore, we found that cating-disordered patients with SIB show

more cluster B (borderline, antisocial) personality disorders than those

without SIB. However, within the SIB group, no difference was found

between those with one or more types of SIB. Herpertz (1995) found that

the borderline personality disorder was present in 52 per cent of the SIB

patients. The histrionic personality disorder was the second most frequent

diagnosis but occurred in only 23 per cent of the subjects. The patients in

Herpertz’s study did not show a high degree of aggression although

antisocial personality disorder was diagnosed in 15 per cent of the subject

‘Thesame can be said about our patients withSIB: they show more features

of the antisocial personality disorder, but on direct measures of aggressive

behaviour they do not score higher than the patients without SIB (as will

be discussed below). This can be explained by the fact that patients with

SIB indeed do not display more aggressive behaviours against others than

patients without SIB. On the other hand, the phenomenon of social

desirability might have distorted our findings: it is to be expected (and

perhaps even more soin eating-disordered patients who value being liked

by others) that aggressive behaviours are underreported

(On our measures of aggression, SIB patients report much more anger

than those without SIB. But with respect to the aggressive behaviours

against others, they do not differ from patients without SIB except for the

acting-out hostility scale of the BDHI, which was higher for the SIB

patients. However, if we eliminate the item which refers to SIB this

statistical significance disappears. The same results concerning anger

‘were found by Hillbrand (1995) who reported that selF-injuring patients

are generally more angry as well as more verbally and physically

aggressive than non-SIB patients (based on observational assessments).

‘Again, the fact that we found less aggressive behaviour in our patients

can be due to the fact that our results are based on a self-report

questionnaire, in which social desirability can play a distorting role.

Furthermore, we found—in the same way as Bennum (1983)—that self

injurious patients show a stronger degree of self-abasement and self-

criticism, including guilt and self-punitiveness, than patients without

SIB. From these findings one may conclude that SIB patients tum their

anger against themselves (and not against others) because of guilt

feelings and self-punitiveness as is often described in the literature

(imeon & Hollander, 2001). However, one can also hypothesize that

patients feel guilty and have to punish themselves after they have injured

[Copyright 208 John Wiley & Sons Lid and Eating Diarders Associaton 393

1, Claes etal Bur. Eat. Disorders Reo. 11, 379-396 (2008)

themselves. Therefore, we think it is important in further research to

clearly differentiate between feelings before and after self-injury.

Our findings provide further confirmation of the strong association

between self-destructive behaviour and childhood histories of emo-

tional, physical and sexual abuse (Simeon & Hollander, 2001): the more

SIB the greater the likelihood of self-reported traumatic experiences in

the past, especially sexual abuse. Furthermore, patients with SIB report

many more dissociative experiences. Although it is difficult to elucidate

the real nature of the linkage, our findings seem to converge into some

association between SIB, dissociative experiences and trauma history

(see also Vanderlinden & Vandereycken, 197). According to Herpertz

(1995), SIB itself includes overwhelming affect: dysphoria, anger,

despair, anxiety etc. that cannot be controlled and mastered. She tends

to conclude that SIB develops out of strong uncontrolled affect rather

than out of urging drives and impulses to act. She therefore supports the

concept of sclf-damaging acts as a form of affect regulation. In

Herpertz’s view poor affect regulation in SIB patients is the underlying

psychopathological dimension resulting in dysphoria and rejection

sensitivity as well as severe disturbance of personality such as

borderline personality disorder and co-morbidity with eating disorders,

substance abuse or other behaviour control problems. Our own research

points in the same direction: the eating-lisordered SIB patients report

more angry feelings, psychiatric symptoms, borderline and antisocial

personality features, and more severe trauma histories,

Last but not least we have to consider the hypothesis of impulse

‘dyscontrol as the basic mechanism, because our patients with SIB report

higher impulsiveness measured as a trait (‘acting without thinking’).

This is supported indirectly by the tendency to show more borderline

features and the fact that SIB is more often found in bulimic patients,

compared to restricting anorectics (Favaro & Santonastaso, 1998;

Favazza, De Rosear, & Conterio, 1989; Lacey, 1993; Welch & Fairburn,

1996). But the impulse dyscontrol hypothesis seems to be contradicted

by a lack of difference in scores on measures of aggressiveness. This,

however, could be due to an underreporting of socially disapproved

behaviours especially in patients who wish to please others and avoid

criticism. Making use of observations along with or instead of self-

reporting measures could give us more information about this issue.

REFERENCES

American Psychiatric Association. (1994), Diagnostic and statistica? manual of

‘mental disorders (Ath ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Copyright © 2008 ob Wiley Sona, Ltd and Eating Disorders Assodati, 304

Eur. Eat, Disonders Rev. 11, 379-396 (2008) Self-njurious Behaviours

Arvindell, W. A, & Etlema, J. H. M. (1986). SC1-90: Handleiding bij een

smultidimensionele psychopathologie-indicator. Lisse: Swets & Zeitlinger.

Bennum, I. (1983). Depression and hostility in self-mutilation, Suicide and Life

Threatening Behavior, 13, 71-84.

Buss, A. H., de Durkee, A. (1957), An inventory for assessing different kinds of

hostility. journat of Consulting Psychology, 21, 343-349,

Buss, A. H., & Perry, M. (1992). The Aggression Questionnaire. Journal of

Personality and Social Peychology, 63, 452859.

Caine, T. M, Foulds, G. A., & Hope, K. (1967). Manual of the Hostility and

Direction of Hostility Questionnaire (HDHQ). London: University Press.

Claes, L,, Vandereycken, W,, é& Vertommen, H. (2001). Self-injurious behaviors

in eating-disordered patients. Eating Behaviors, 2, 263-272.

DiClemente, R.J,, Ponton, L. E, & Hartley, D. (1991). Prevalence and correlates

‘of cutting behavior: Risk for HIV transmission. Jounal of the American

Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 30, 735-739.

Dulit, R. A., Fyer, M.R,, Leon, A. C,, Brodsky, B.S, & Frances, A, J. (1994),

‘Clinical correlates of self-mutilation in borderline personality disorder.

American journal of Peychiatry, 151, 1305-1311

Eysenck, $. B.G., Pearson, P.R., Fasting, G., & Allsopp, JF. (1985). Age norms

for impulsiveness, venturesomeness and empathy in adults. Personality

and Individual Differences, 6, 613-619.

Favaro, A., & Santonastaso, P. (1998). Impulsive and compulsive self-injurious

behaviour in bulimia nervosa: Prevalence and psychological correlates.

Journal of Neroous and Mental Disease, 186, 157-165.

Favaro, A., & Santonastaso, P. (1999). Different types of self-injurious behavior

in bulimia nervosa. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 40, 57-60.

Favaro, A., & Santonasiaso, P. (2000). Self-injurious behavior in anorexia

nervosa. Journal of Neroous and Mental Disease, 188, 537-542.

Favazza, A.R,, De Rosear, L,, & Conterio, K. (1986). Self-mutilation and eating.

disorders. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behaviour, 19, 352-361

Ghaziuddin, M, Tsai, L., Naylor, M.,6Ghaziuddin, N. (1992). Mood disorderin

a group of self-cutting adolescents. Acta Paedopsychiatrica, 5, 103-105.

Herpertz, 5, (1995). Selfinjurious behaviour: Psychopathological and nosolo-

gical characteristics in subtypes of self-injurers. Acta Psychiatrica

Seandinavica, 91, 57-68.

Hillbrand, M. (1995). Aggression against self and aggression against others in

violent psychiatric patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology,

63, 668-671

Jacobs, B. W,, & Isaacs, S. (1986). Pre-pubertal anorexia nervosa: A retrospective

controlled study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 27, 237-250.

Lacey, J. H. (1993). Self-damaging and addictive behaviour in buliraia nervosa.

British journal of Psychiatry, 163, 190-194.

Langbehn, D. , & Pfohl, B. (1993). Clinical correlates of self-mutilation among,

psychiatric inpatients, Armals of Clinical Psychiatry, 5, 45-51.

Leibentuft,E., Gardner, D.L., & Cowdry, R. W. (1987). The inner experience of

the borderline self-mutilator. Journal of Personality Disorders, 1, 317-324

Copyright © 2009 Jot Wey & Sons, Li an Eating Disorders Associaton, 395

L. Claes et al Eur. Eat. Disorders Reo, 11, 379-996 (2008)

Mitchell, E,, Boutacoff, L.1,, Hatsukami, D,, Pyle, R. L., & Eckert, E. D. (1986).

Laxativa abuse as a variant of bulimia, Journal of Neroous and Mental

Disease, 174, 174-176.

Mood, A. M., Graybill, F. A., & Boes, D. C. (1974). Introduction to the theory of

statistics. Third Edition. Singapore: McGraw-Hill Book Company.

Nijonhuis, F., van der Hart, O, & Vanderlinden, J. (1998). Vragenlijst belastende

ervaringen (Traumatic Experiences Questionnaire). Amsterdam: Uni

versity of Amsterdam, Department of Psychology.

Newton, JR, Freeman, C.P,,& Munro, J. (1993), Impulsivity and dyscontrol in

Bulimia nervosa: Is impulsivity an indepent phenomenon or a marker

of severity? Acta Psyckiatrica Scandinavica, 87, 389-294.

Pattison, E. M,, & Kahan, J. (1983). The deliberate self-harm syndrome.

“American Journal of Psychiatry, 140, 867-872.

Probst, M,, Vandereycken, W., Van Coppenolle, H., & Vanderlinden, }. (1995).

‘The Body Attitude Test for patients with an eating disorder:

Psychometric characteristics of a new questionnaire, Fating Disorders:

‘The Journal of Treatment and Prevention, 3, 133-144.

Rudd, M. D. (1986). The prevalence of suicidal ideation among college students.

‘Suicide and Life Threatening Bekavior, 19, 173-183.

Schotte, C.K. W., De Doncker, D,, Vankerckhoven, C., Vertommen, H., &

Cosyns, P. (1998), Self-report assessment of the DSM-IV personality

disorders. Measurement of trait and disiress characteristics: The ADP-

IV. Psychological Medicine, 28, 1179-1188.

‘Simeon, D,, & Hollander, E. (Eds). (2001). Self injurious behaviors: Assessment and

treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Simeon, D., Stanley, B., Frances, A,, Mann, J. J, Winchel, R., & Stanley, M.

(1992). Self mutilation in personality disorders: Psychological and

biological correlates. American Journal of Psychiatry, 149, 221-226.

Spietberger, C.D. Krasner 5.8, &Solomon, P. (1988). Theexperience, expression

‘and control of anger. In M. P.Janisse Ed), Individual diferences,stressand

Irealth psychology (pp. 89-108). New York: Springer-Verlag.

Suyemoto, K. L, (1998). The functions of selF-mutilation. Clinical Psychology

Review, 18, 531-354.

Vandereycken, W. (1993). The Eating Disorders Evaluation Scale. Eating

Disorders: The Journal of Treatment and Prevention, 1, 115-122.

Vanderlinden, J, & Vandereyeken, W. (1997). Trauma, dissociation, and impulse

dyscontrol in eating disorders. New York: Brunner/Maz¢h

Vanderlinden, J, Van Dyck, ., Vandereycken, W., Vertommen, H., & Verkes,R

J.(4993). The Dissociation Questionnaire (DIS-Q): Developmentofa new

self-report questionnaire. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 1, 21-27.

Walburg, J. A., & van Limbeek, J. (1985). Munchen: Alcokol Test. Lisse: Swets &

Zoitlinger,

Welch, §. L., & Fairburn, C. G. (1996). Impulsivity or comorbidity in bulimia

nervosa: A controlled study of deliberate self-harm and alcohol and

drug misuse in a community sample. British Journal of Psychiatry, 169,

451-458,

‘Copyright 210 Jon Wiley & Sons, Lid an Eating Disorder Assocation. 396

Copyright of European Eating Disorders Review is the property of John Wiley & Sons

Inc. and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a

listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may

print, download, or email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Regulated Professions AustraliaDocument8 pagesRegulated Professions AustraliaAlicia SvetlanaNo ratings yet

- Social Learning TheoryDocument6 pagesSocial Learning TheoryAlicia SvetlanaNo ratings yet

- Bernstein PDFDocument15 pagesBernstein PDFVirgílio BaltasarNo ratings yet

- Written Emotional ExpressionDocument11 pagesWritten Emotional ExpressionAlicia SvetlanaNo ratings yet

- Suicidality in BDDDocument15 pagesSuicidality in BDDAlicia SvetlanaNo ratings yet

- Bandura - Sociocognitive Self-Regulatory Mechanisms Governing Transgressive BehaviourDocument11 pagesBandura - Sociocognitive Self-Regulatory Mechanisms Governing Transgressive Behaviournikatie4846No ratings yet

- Uso de Terapias Alternativas en MexicoDocument10 pagesUso de Terapias Alternativas en MexicoAlicia SvetlanaNo ratings yet

- Written Emotional ExpressionDocument11 pagesWritten Emotional ExpressionAlicia SvetlanaNo ratings yet

- Encuesta Nacional Epidemiologia PsiquiatricaDocument16 pagesEncuesta Nacional Epidemiologia Psiquiatricaapi-3707147100% (2)

- Effect of Cortisol On Memory in Women With BPDDocument12 pagesEffect of Cortisol On Memory in Women With BPDAlicia SvetlanaNo ratings yet

- Gene Envirmonment Interaction in Prediction of Behavior Inhibition in Middle ChildhoodDocument6 pagesGene Envirmonment Interaction in Prediction of Behavior Inhibition in Middle ChildhoodAlicia SvetlanaNo ratings yet

- Emotional Intelligence and Locus of Control ThesisDocument62 pagesEmotional Intelligence and Locus of Control ThesisAlicia SvetlanaNo ratings yet

- GAD Review For DSM 5Document14 pagesGAD Review For DSM 5Alicia SvetlanaNo ratings yet

- Developmental Pathways in ODD and CD (1-2p)Document13 pagesDevelopmental Pathways in ODD and CD (1-2p)Alicia SvetlanaNo ratings yet

- Alexithymia, Eating Behavior and Self EsteemDocument8 pagesAlexithymia, Eating Behavior and Self EsteemAlicia SvetlanaNo ratings yet

- Depression, Alexithymia and Eating Disorders PDFDocument11 pagesDepression, Alexithymia and Eating Disorders PDFAlicia SvetlanaNo ratings yet

- Comorbidity of Anx DX and EDxDocument7 pagesComorbidity of Anx DX and EDxAlicia SvetlanaNo ratings yet

- Catharsis, Rumination, Distraction, Anger and Aggressive Responding PDFDocument8 pagesCatharsis, Rumination, Distraction, Anger and Aggressive Responding PDFAlicia SvetlanaNo ratings yet

- ANSIEDAD Y DEPRESIÓN, EL PROBLEMA de Su DiferenciaciónDocument9 pagesANSIEDAD Y DEPRESIÓN, EL PROBLEMA de Su DiferenciaciónjuaromerNo ratings yet

- Craske - PD Review For DSM 5Document20 pagesCraske - PD Review For DSM 5Alicia SvetlanaNo ratings yet

- Attentionalbias To Threat and Emotional Response To Biological Challenge PDFDocument19 pagesAttentionalbias To Threat and Emotional Response To Biological Challenge PDFAlicia SvetlanaNo ratings yet

- Abnormalities of Visual Processing and Frontostriatal Systems in BDDDocument9 pagesAbnormalities of Visual Processing and Frontostriatal Systems in BDDAlicia SvetlanaNo ratings yet

- APA Ethics Code PDFDocument18 pagesAPA Ethics Code PDFAlicia SvetlanaNo ratings yet

- Anxiety and Anxiety Disorders in Children and Adolescents Implications For DSM 5 PDFDocument44 pagesAnxiety and Anxiety Disorders in Children and Adolescents Implications For DSM 5 PDFAlicia SvetlanaNo ratings yet

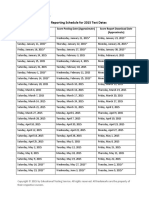

- Score Reporting Schedule Test DatesDocument3 pagesScore Reporting Schedule Test DatesAlicia SvetlanaNo ratings yet

- Colegio Ontario SupervisionDocument6 pagesColegio Ontario SupervisionAlicia SvetlanaNo ratings yet

- A Comparison of Insight in BDD and OCDDocument14 pagesA Comparison of Insight in BDD and OCDAlicia SvetlanaNo ratings yet

- Abnormalities of Visual Processing and Frontostriatal Systems in BDDDocument9 pagesAbnormalities of Visual Processing and Frontostriatal Systems in BDDAlicia SvetlanaNo ratings yet

- Colegio Ontario CuotasDocument1 pageColegio Ontario CuotasAlicia SvetlanaNo ratings yet