Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Stevenson Meares (1992) An Outcome Study of Psychotherapy For Patients With Borderline Personality Disorder

Uploaded by

bpregerOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Stevenson Meares (1992) An Outcome Study of Psychotherapy For Patients With Borderline Personality Disorder

Uploaded by

bpregerCopyright:

Available Formats

,

An Outcome Study of Psychotherapy for Patients

With Borderline Personality Disorder

Janine Stevenson, M.B., B.S., F.R.A.N.Z.C.P.,

and Russell Meares, M.D., F.R.A.N.Z.C.P., F.R.C.Psych.

Obiective; This study evaluated the effectiveness ofwell-defined outpatient psychotherapy for

patients with borderline personality disorder. Method: Thirty patients with borderline personal-

ity disorder diagnosed according to the DSM-lij criteria were given twice weekly outpatient

psychotherapy for 12 months by trainee therapists who were closely supervised. The treatment

approach was based on a psychology ofself (this term being used in its broad sense), and strong

efforts were made to ensure that all therapists adhered to the treatment model. Outcome meas-

ures included frequency ofuse ofdrugi(both prescribed and illegal), number ofvisits to medical

professionals, number of episodes of violence and self-harm, time away from work, number of

hospital admissions, time spent as an inpatient, score on a self-report index of symptoms, and

number of DSM-III criteria (weighted for frequency, severity, and duration) fulfilled. Results'

The subjects showed statistically significant improvement from the initial assessment to the end

ofthe year of follow-up on every measure. Moreover, 30% ofthe subjects no longer fulfilled the

DSM-Ill criteria for borderline personality disorder. This improvement had persisted 1 year after

the cessation oftherapy. Conclusions: The results suggest that a specific form ofpsychotherapy

is of benefit for patients with borderline personality disorder.

(Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:358-362)

r,t

U ntil comparatively recently, no treatment was

available for persons with severe personality dis-

order. Individuals so badly damaged were consideted

sions per week. Measures were taken to assess the

tients before, during, and after treatment.

"unanalyzable." However, over the last two decades, Treatment Model

methods of treating borderline and narcissistic person-

alities have been steadily evolving. The aim of this pro- We made considerable efforts to develop a cohmD!.

ject was to evaluate the effectiveness of an identifiable consistently applied, and identifiable treatment olp

form of psychotherapy, conducted by trainee therapists proach. It was based on the notion that borderline per

working under dose supervision, in the management of sonality disorder is a consequence of a disruption in thl

outpatients with borderline personality disorder. As far development of the self. The principal assumption ,.

as we are aware, this report describes the first prospec- that a certain kind of mental activity, found in re\"cnl

tive study of this kind. and underlying symbolic play, is necessary to the gen

eration of the self. This kind of mental activity is non

linear, associative, and affect laden. In early life its pre'

THE STUDY ence depends on a sense of "union" with caregivers, in

which they are experienced as extensions of the derel

A group of patients with severe personality disorder oping individual's subjective life (1, p. 243). Develop

were given psychotherapy for 12 months, at two ses- ment is disrupted through repeated "impingements" Ie

of the social environment, which have an impact on rh,

child rather like that of a loud noise. This effect arise'

Received March 27, 1990; revision received July 22, 1991; accepted through actual stimuli (abuse of various kinds is com

Aug. 29, 1991. From the Department of Psychiatry, Westmead Hos-

pital. Address reprint requests to Dr. Meares, Department of Psychia-

mon in the early lives of borderline patients [3-51 '.

try, Westmead Hospital, Darcy Road, Wesrmead, New South Wales through high anxiety, and through responses that dr'

2145, Australia. not connect with the child's immediate reality and S<'

Supported by a New South Wales Institute of Psychiatry research seem to come from "outside."

grant to Dr. Stevenson.

The authors thank Prof. D. Newell for assistance with the statistical

The aim of therapy is maturational. Specifically, it is '"

analysis. help the patient discover, elaborate, and represent a per

Copyright 1992 American Psychiatric Association. sonal reality (6), i.e., a reality that relates to an inner hte

358 Am] Psychiatry 149:3, March 199~

JANINE STEVENSON AND RUSSELL MEARb

Jnd that has an affective core (7). The first task is to es- had been physically attacked and injured; had been hu-

.ablish the enabling atmosphere in which the generative miliated after revelation of an emotional state; had felt

~ental activity can arise. In order to do so, the therapist "paranoid"; and had been enraged. A disjunction was

:nust imaginatively immerse himself or herself in the em- signaled by the change from inner concerns ("images")

,rvonic inner life of the patient. Empathy, however, in- to outer events, by the affect which escalated from agi-

,,,itably fails. The second main task of the therapist is to tation to anger, and by the alteration in self state indi-

detect these failures, to focus with the patient on his or cated by the pompous voice. It is apparent that the

her experience at the moment of the failures, and then to therapist's response was sensed as an intrusion (16). In

Jllow these experiences to be the starting point of expe- one sense it was "correct," in that it was accurate; in

nential explorations. Such empathic failures, or disjunc- another it was not, since it produced a disjunction. The

:Ions, are indicated by 1) negative affect (e.g., deadness, "correct" subsequent response is to explore the effect

Jnxiety), 2) linear thinking, 3) an orientation toward of the first response. This requires skill, since it may be

("ents and the outer world, 4) a change in self state (e.g., sensed as a second intrusion.

devaluing, grandiose), and 5) emergence of transference A second difficulty in rating transcripts is that the nu-

"henomena (8). An illustrative therapy session, which in- ances of the interchange are often reflected in changes

:Iudes a further description of the treatment method, is in voice, which are a matrer of subjective judgment. In

reproduced elsewhere (9). the incident just described, for example, the change of

This therapeutic approach was influenced by Robert voice at "Good point" was not noticed by the therapist.

Hobson's work with borderline patients at the Bethle- Despite these problems, a linguistic analysis of tran-

hem Royal Hospital, London, during the 1960s (10). scripts, based on Halliday's systemic grammar (17), is

The theoretical framework includes essential elements underway in order to provide data for a future manual

frOm the work of Kohut (11) and Winnicott (12)_ The that will address a limited range of therapeutic issues.

model is consistent with Pine's description of the "bor-

Jerline-ehild-to-be" (13). Sub;ects

Whether therapists adhere to the therapeutic model is

a major problem in psychotherapy outcome research. Patients were referred by psychiatrists, allied health

In this project, the problem was approached in three professionals, community clinics, and inpatient units,

main ways. First, all therapists were given instruction and some were self-referred. Eighty-five consecutive

In the method by means of weekly seminars. Second, all patients were rated by three independent psychiatrists

therapy sessions were audiotaped and replayed with a according to the DSM-III criteria for borderline per-

,upervisor once a week. In this way, the supervisor could sonality disorder in a diagnostic interview that included

make judgments about adherence to the model and sug- the Diagnostic Interview for Borderline Patients (18).

gest alterations of therapists' behavior. Third, in order They were then seen by a consultant psychotherapist

ro achieve maximum uniformity of approach, supervi- who made a diagnosis of borderline personality disor-

<,ors, on occasion, supervised together. der on dynamic grounds. Potential subj ects were also

Ideally, a manual that defines therapeutic behavior is required to display persisting social dysfunction (e.g.,

"sed to establish adherence, in the manner of Luborsky unemployment for more than 12 months, absence of

14). This might be done by independent judges rating or severely dysfunctional interpersonal relationships,

[[anscripts, which facilitates replication studies and antisocial behavior). Sixty-seven patients fulfilled these

also matching of outcome against the treatment model. criteria. All 67 had previously been unsuccessfully in-

However, in this case such a process is complex, since volved in other forms of therapy for a period of not less

rhe therapeutic field is "intersubjective" (15). The thera- than 6 months.

peutic response cannot be judged as "correct" before it Eight of these patients were considered unsuitable for

is made. Its suitability is evident only after it has been psychotherapy for the following reasons: borderline in-

made. For example, a patient who had spent much of tellectual retardation (N=2), language difficulty (N=2),

his early life in an orphanage and who could not re- antisocial and uncontrollable violent behavior (N=1),

member anything before the age of 10 began a session and failure to keep three consecutive appoinrments

b" announcing that his girlfriend was pregnant. This (N=3). F'f):y-nine potential subjects now remained.

appeared to be "no problem," since she would get an After tne course of treatment was explained, 11 pa-

abortion. After a few connecting sentences, the patient, tients declined treatment or accepted but failed to keep

showing litrle affect, went on to say that he wondered " further appointments. At this stage written consent was

whether some early memories were beginning to be re- , obtained from the remaining 48 patients, all initial as-

covered, since he had had "images" of himself as a ter- sessments were performed, an appointment was made

rified child being dragged from under a bed, presum- for an interview with a close friend or relative of each

,lbly to be taken to the orphanage. The therapist then patient, and the patient was assigned to a therapist. Af-

remarked that the forthcoming abortion seemed to ter 6 months of therapy and at the conclusion of ther-

have triggered feelings relating to his being "gotten rid apy, further assessments were performed. During the

of' by his own mother. The patient said, "Good point," 12 months, eight patients dropped out of therapy,

In a rather pompous voice. He then recounted, without mostly in the first 3 months, before a firm relationship

Jny apparent reason, successive incidents in which he had been established with the therapist. This left 40 pa-

,m J Psychiatry 149:3, March 1992 359

PSYCHOTHERAPY FOR BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER

tients who completed 12 months of therapy. (Seven of for the entire year preceding and for the year followin,

these elected to continue therapy for a longer time and therapy. They included amount of time away from

so were excluded from the present study. They were work (in months), use of medical facilities (number OJ

doing well. The decision to omit them was on the outpatient visits to a medical facility each month.

grounds that they had not terminated and that their quantity of drugs (prescribed and illegal) used On .1

current state might seem to inflate the value of the treat- daily basis, self-destructive behavior and outwardly d:.

ment.) It was explained to the 33 patients who com- rected violence (number of episodes over a 12-momh

pleted the 12-month course of therapy that they would period), and number of hospital admissions and tim"

be contacted a year later "to see how they were doing." spent as an inpatient (in months). Information was oh-

Of these 33 patients, three could not be contacted. tained from the patient, friends or relatives, medica,

Thus, ofthe 48 patients who accepted therapy, 37 com- records, and referral sources. Such methodology rr-

pleted all assessments. Seven continued therapy and duces errors that may be inherent in the patient's OWn

were excluded from the present study. The remaining report. All assessments were performed by the researrh

30 patients are the subject of this article. psychiatrist U.S.), who was not involved in the therapI

process.

Therapists and Supervisors The MINITAB data analysis software was used n,

analyze results. Paired t tests were used to explore the

The 20 therapists we~e relatively untrained in psycho- 'i:lifferences between the independent variables befor,'

therapy, since they were trainee psychiatrists (1-3 years and atter therapy, followed by post hoc Bonferroni ad

of psychiatry training, 1-2 years of postgraduate medi- justments of alpha levels.

cal training), registered nurses, and psychologists. They

were young (average age=30.6 years-dose to the aver-

age age of the patients), 12 were single and eight were RESULTS

married, and 11 were male and nine female. Six had

postgraduate qualifications. The mean age of the subjects was 29.4 years (SD=

Although the supervisors had different training experi- 7.9). Nineteen were female and 11 male. Nine were

ences, they developed fairly consistent supervisory behav- married. Only three had not completed junior high

ior. Two were trained by Robert Hobson, a third was a school; six had undertaken college srudies. Eight suh-

psychoanalyst trained in London, a fourth was oriented jects had received long-term institutional or foster carr.

toward Sullivan's interpersonal psychology, and two oth- None had serious medical problems. Twenty-tw"

ers were oriented toward Kohut's self psychology. (73.3%) were receiving government financial assistanc,

(sickness benefits, invalid pension, unemploymem

benefits, etc.). The remaining eight worked erraticali<

METHOD in various nonskilled (N=2), skilled (N=3), and profes-

sional (N=3) occupations. Ouly two owned their own

Demographic data-age, sex, occupation, partner's homes; the remainder were renting privately, livin~

occupation, marital status, education, physical health, with friends or relatives, or in government housing.

place of residence, parent's or surrogate parent's occu- There was a significant reduction in the number a!

pation, and country of origin-were collected on all DSM-III criteria fulfilled at follow-up (mean=10.50

subjects. (A large number of patients had been adopted, compared with pretreatment (mean=17.40) (table 1'.

placed in foster homes, or institutionalized early in life.) The most frequently observed changes were reduction,

The number of DSM-III criteria for borderline person- in impulsivity, affective instability, anger, and suicid.1i

aliry disorder fulfilled by the subject was determined. Each behavior. It is also noteworthy that at follow-up, oni<

was weighted on the basis of frequency, severity, and du- 70% (N=21) of the 30 subjects fulfilled the DSM-JIi

rarion, and the total score was recorded. (A number of criteria for borderline personality disorder, compareJ

patients also fulfilled the DSM-III criteria for other per- with 100% before treatment.

sonality disorders, such as schizotypal, histrionic, narcis- There was a marked and statistically significant im-

sistic, and antisocial.) No modifications were made fol- provement on all seven objective behavioral measure,

lowing publication of DSM-III-R, since the criteria were over the 12 months following therapy compared with

essentially unchanged. the 12 months before therapy when pretreatment score,

The Cornell Index (19) provided a self-report rating were compared with follow-up scores (table 1); for ex-

of symptoms. An initial measure was taken to assess ample, medical office visits dropped to only one-se l '

severity of dysfunction and as a baseline for later com- enth of pretreatment rates (3.50 to 0.47 per patient per

parison. This index is generally used for quite disabled month), and self-harm and drug use dropped 10 onf-

patients. Consequently, it was considered more suitable fourth of pretreatment rates.

for our population of subjects than instruments used Cornell Index scores had dropped significantly 12

for neurotic patients. Measures were taken at the initial months after treatment when compared with pretreat-

assessment, atter 6 months of therapy, atter 12 months ment levels (table 1); the rate of change over the 2 year,

of therapy, and at follow-up 12 months later. was approximately linear (mean scores at 0, 6, 12, aoo

Objective behavioral measures were collected en bloc 24 months were 42.63, 41.00,33.60, and 28.63).

360 Am J Psychiatry 149:3, March 19 92

JANINE STEVENSON AND RUSSELL MEARES

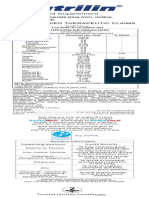

TABLE 1. Scores of 30 Patients on Behavioral Measures, the Cornell Index, and OSMIII Criteria for Borderline Personality Disorder fat the 12

Months Preceding and Following Psychotherapy

One Year Before One Year Afrer

Therapy Therapy Paired t Test

.\leasure Mean SD Mean SD t (dI=29j p

Violent behavior (episodes per year) 2.70 4.05 0.80 1.80 3.69 <0.001

Drugs used (number per day) 3.80 3.42 0.63 0.80 5.05 <0.001

.\tedical visits (number per month) 3.50 2.75 0.47 0.57 6.16 <0.001

Self-harm (episodes per year) 3.77 4.66 0.83 1.18 3.82 <0.001

Time away from work (months per year) 4.47 4.10 1.37 2.57 4.90 <0.001

Hospital admissions (number per year} 1.77 1.52 0.73 1.02 3.03 <0.01

rime as an inpatient (months per year) 2.87 2.33 1.47 1.87 2.73 <0.05

Cornell Indexa score (at end of year) 42.63 14.90 28.63 13.35 5.68 <0.001

DSM-Ill score b (at end of year) 17.40 2.87 10.50 5.08 7.48 <0.001

'.\ self-report rating of symptoms.

;'~umber of criteria for borderline personality disorder (weighted for frequency, severity, and duration) fulfilled by subject.

DISCUSSION the other hand, since personality disorder is relatively

enduring, comparisons between different periods of the

Thirty patients with the diagnosis of borderline per- patients' lives offer a suitable means of obtaining a con-

sonality disorder were treated for 12 months. They trol. Thus, 1 year of the patients' lives before treatment

showed significant symptomatic and behavioral im- was compared with 1 year after.

provement. Moreover, 30% no longer fulfilled the This study cannot be compared with most others in

DSM-Ill criteria for borderline personality disorder. this area, since they usually concern inpatients and are

Improvement was maintained at follow-up 12 months retrospective. Tucker et al. (20), however, reported on

later. These findings suggest that a specific form of ther- a prospective study of inpatients, the results of which,

apy, supervised in a focused and coherent way, is help- over 2 years, were favorable.

ful to a group of people who, most studies report, "do Of particular interest in the present study is the find-

nO! fare well at follow-up" (20). ing that patients were able to terminate treatment

Studies of the management of borderline personality and maintain their improvement. Alternative expla-

disorder have been criticized on the grounds that diag- nations for the good outcome did not seem plausible.

nostic criteria are not clear, outcome measures are rela- Those that were considered included spontaneous re-

tively subjective, designs are retrospective rather than mission, a ceiling effect, selective attrition, and inter-

prospective, and there are no control measures (21). In current therapy.

this study we attempted to overcome these problems. Spontaneous remission seemed an unlikely explana-

The palients were carefully diagnosed according to lion for the results. In a previons study of psychother-

DSM-IlI, the outcome measures were objective, and the apy outcome, a period of 6 months with continuous

study was prospective. The ptincipal difficully, how- symptoms was used to differentiate patients with

ever, concerned the method of control; we used control chronic illness from Ihose whose illness remilted (H.

measures rather than control subjects. Brodaty, unpublished doctoral thesis, 1985). All pa-

No sensible or ethical solution to the problem of con- tients in our trial had continuous symptoms for 12

trol subjects was evident to us. Ideally, a "placebo" months, the majority for many years.

therapy would be compared with Ihe treatment model, A second possible explanation for the improvement

III the manner of pharmacotherapy studies. The control of our patients might be a so-called ceiling effect. Put

,ubjects would spend the same amount of time as the - another way, were the patients so disturbed that they

lither patients in sessions with a therapist. The thera- could deteriorate no further? The histories of our pa-

pist, however, blind to these circumstances, would be tients did not support this possibility. For example,

instructed by a supervisor to make interventions likely many had had inpatient treatment, but no patient ell-

to have no therapeutic effect. Such a design seemed un- tered the trial at one of these periods of crisis.

<lCceplable from several points of view, including the The possibility that selective patient attrition dis-

communal. The clinic is the only one of its kind. The torted the results of this study was not supported. There

expectation of referral sources was that their patients, was no evidence that the more disturbed patients had

who had usually already received extensive and various dropped out. Comparisons were made between trial

treatments including drugs and ECT, would receive a subjects and dropouts on demographic data (age, sex,

different" therapy, specially geared toward patients occupation, social class, etc.), Cornell Index scores, ful-

with severe personality disorders. Attempts to assign fillment of DSM-III criteria, and behavioral measures.

patients to treatments they had previously encountered No significant differences were found on any measure.

resulted in these patients' dropping out. An alternative, There was a tendency for the dropouls to live farther

the use of patients on the waiting list as control subjects, from the Ireatmenr center, although this difference did

;" impracticable with such an unstable population. On not reach statistical significance. Furthermore, the

\/111 Psychiatry 14Y:3, March 1992 361

PSYCHOTHERAPY FOR BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER

dropout rate was low-16%-eompared with the rates Childhood experiences in borderline patient's. Corupr Psychiatn

1989; 30018-25 .

in previous studies (22, 23). 6. Meares R: The secret and the self: on a new direction in psycho.

Finally, any intercurrent treatments were carefully therapy. Aust NZ] Psychiatry 1987; 21:545-559

monitored in this study. On entering the trial, all pa- 7. Emde R: The pre-representational self and its affective core. PSI-

tients had rheir medications gradually withdrawn. choana! Study Child 1983; 380165-192 .

Hypnotics and minor tranquilizers were given to a mi- 8. Meares R: The fragile Spielraum: an approach to transmurill~

internalization, in Progress in Self Psychology, vol 6: The Rc,lli-

nority of patients on occasion and to patients who ties of Transference. Edited by Goldberg A. Hillsdale, Nj, AnJ-

needed hospitalization. Those few patients who needed lytic Press, 1990

hospital admission during therapy, usually during a cri- 9. Meares R: Transference and the play space: towards a new basi..:

sis, continued to receive psychotherapy, while the ward metaphor. Contemporary Psychoanal (in press)

10. Hobson RF: Forms of Feeling: The Heart of Psychotherapy. Lon-

provided a supportive, containing environment, but no don, Tavistock Publications, 1985

other "treatment" was given. At each assessment inter- 11. Kohut H: How Does Analysis Cure? Contributions to the P5\"-

view interviewers asked about intercurrent treatment, chology of the Self. Edited by Goldberg A, Stepansky P. Chicag;l.

appointments with other doctors, and alternative thera- University of Chicago Press, 1984

pies. Little evidence of rhese was found. One patient 12. Winnicott DW: Playing and Reality. London. Tavistock Public.l

'-tions, 1971

who continued to see a previous therapist and who re- 13. Pine F: On the development of the "borderline-child-to-be." Am

ceived medications from him eventually dropped out. J Onhopsychiatry 1986; 56:3:450-457

Most patients had more or less exhausted other treat- 14. Luborsky L: Principles of Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy: A l\.1an

ment options before referral into our trial. ual for Supportive-Expressive Treatment. New York, Basi..:

Books, 1984

In conclusion, this repon suggests that a specific form 15. Stolorow RD, Brandchaft B, Atwood GE: Psychoanalytic Treat-

of psychotherapy is of benefit for borderline patients. ment: An Inrersubjective Approach. Hillsdale, NJ, Analyti.:

All patients will be followed up at 5 and 10 years. The Press, 1987

cost effectiveness of treatment and aspects of the thera- 16. Meares R: The secret, lies and the paranoid process. Contempo

peutic process that are related to change are the basis rary Psychoanal1988; 24:650-666

17. Halliday M: An Introduction to Functional Grammar. London.

for subsequent repons. Arnold, 1985

18. Gunderson .IG, Kolb JE, Austin D: The Diagnostic Interview for

Borderline Patients. AmJ Psychiatry 1981; 138:896-903

REFERENCES

19. Weider A, WoIffH, Brodman K, Mittelman B, Wechsler D: Cor~

1. Piaget]: The Language and Thought of the Child. London, Rout- nell Index. New York, Psychological Corp, 1948

ledge & Kegan Paul. 1959 20. Tucker L, Bauer SF, Wagner S, Harlam D, Sher I: Long-tenn

2. Winnicott DW: The Maturational Processes and the Facilitating hospital treatment of borderline patients: a descriptive outcome

Environment. New York, International Universities Press. 1960 study. Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144:1443-1448

3. Herman JL, Perry Je, van dec Kolk BA: Childhood trauma in 21. Aronson T: A critical review of psychotherapeutic treatments 01

borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146: borderline personality. J Nerv Ment Dis 1989; 177:511-528

490-495 22. Waldinger R, Gunderson J: Completed psychotherapies wirh

4. Ludolph PS, Westen D, Misle B, Jackson A, Wixom J, Wiss Fe: borderline patients. Am J Psychother 1984; 38:190-201

The borderline diagnosis in adolescents: symptoms and develop- 23. Gunderson J. Frank A, Ronningstam E, Wachter S, Lynch ,",

mental history. Am] Psychiatry 1990; 147:470-476 Wolf P: Early discontinuance of borderline patients from psy-

5. Zanarini M. Gunderson J, Marino F, Schwartz E, Frankenburg F: chotherapy.] Nerv Ment Dis 1989; 177:38-42

362 Am] Psychiatry 149:3, March 1992

You might also like

- The Naturalistic Course of Major Depression N The Absence of Somatic TherapyDocument6 pagesThe Naturalistic Course of Major Depression N The Absence of Somatic TherapyCarlos CostaNo ratings yet

- BA Treatments for Depression Meta-Analysis and ReviewDocument29 pagesBA Treatments for Depression Meta-Analysis and ReviewJoão Gabriel Ferreira ArgondizziNo ratings yet

- Conceptual Models in Mental Health NursingDocument10 pagesConceptual Models in Mental Health NursingPrasanth Kurien Mathew100% (7)

- Narrative Cognitive Behavior Therapy For PsychosisDocument12 pagesNarrative Cognitive Behavior Therapy For PsychosisGanellNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Psychological Intervention On Cognitive Appraisal and Level of Anxiety in Dialysis Patients: A Pilot StudyDocument4 pagesThe Influence of Psychological Intervention On Cognitive Appraisal and Level of Anxiety in Dialysis Patients: A Pilot StudyoanacrisNo ratings yet

- Terapia Cognitivauma Retrospectiva 9780470479216.corpsy0198Document3 pagesTerapia Cognitivauma Retrospectiva 9780470479216.corpsy0198RayssaNo ratings yet

- Rou Saud 2007Document11 pagesRou Saud 2007healliz36912No ratings yet

- Personality DisordersDocument13 pagesPersonality DisordersAnnisa Danni KartikaNo ratings yet

- Artigo Depressão Na TCCDocument21 pagesArtigo Depressão Na TCCLarissa BenderNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Abnormal Behavior in Historical ContextDocument14 pagesChapter 1 Abnormal Behavior in Historical ContextKyle Mikhaela NonlesNo ratings yet

- Psychoanalytic Versus Psychodynamic Therapy For DepressionDocument19 pagesPsychoanalytic Versus Psychodynamic Therapy For DepressionNéstor X. PortalatínNo ratings yet

- Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy For DepressionDocument7 pagesCognitive-Behavioral Therapy For DepressionTri Utami HandayaniNo ratings yet

- A Brief Behavioral Activation Treatment For D e P R e S S I o NDocument12 pagesA Brief Behavioral Activation Treatment For D e P R e S S I o NVARGAS MORENO HANNA VALERIANo ratings yet

- Personal Therapy HogartyDocument15 pagesPersonal Therapy HogartyBernardo LinaresNo ratings yet

- Dissociative Identity DisorderDocument11 pagesDissociative Identity DisorderIdilbaysal9100% (2)

- J Yebeh 2009 02 016Document6 pagesJ Yebeh 2009 02 016Oscar FernandezNo ratings yet

- Psychotherapy For Treating Anxiety DisordersDocument11 pagesPsychotherapy For Treating Anxiety DisordersShaista ArshadNo ratings yet

- PsychoSexualPsych PDFDocument7 pagesPsychoSexualPsych PDFtonyNo ratings yet

- Dissociation Affect Dysregulation Somatization BVDKDocument22 pagesDissociation Affect Dysregulation Somatization BVDKkanuNo ratings yet

- Tham khảo Multiple baseline study exampleFileDocument12 pagesTham khảo Multiple baseline study exampleFileHằng Trần Thị ThúyNo ratings yet

- The Psychodynamic Diagnostic ManualDocument3 pagesThe Psychodynamic Diagnostic ManualJrtabletsmsHopeNo ratings yet

- Day 1 Intro RV Rushed Version For 2018Document30 pagesDay 1 Intro RV Rushed Version For 2018api-391411195No ratings yet

- Early signs of schizophrenia relapseDocument11 pagesEarly signs of schizophrenia relapseamelia welindaNo ratings yet

- EJ880555Document14 pagesEJ880555taman ooNo ratings yet

- Horowitz Event ScalesDocument10 pagesHorowitz Event Scalesvota167No ratings yet

- Assignment On Psychotherapy: Submitted by Maj Mercy Jacob 1 Yr MSC Trainee Officer Con CH (Ec) KolkataDocument27 pagesAssignment On Psychotherapy: Submitted by Maj Mercy Jacob 1 Yr MSC Trainee Officer Con CH (Ec) KolkataMercy Jacob100% (2)

- Personality Dimensions and Depression: Review and CommentaryDocument11 pagesPersonality Dimensions and Depression: Review and Commentarysofia valloryNo ratings yet

- Task Analysis Emotional ProcessingDocument13 pagesTask Analysis Emotional ProcessingGloria KentNo ratings yet

- Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Women's Body-Image DissatisfactionDocument9 pagesCognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Women's Body-Image DissatisfactionAnda F. CotoarăNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Therapy of Affective Disorders. BeckDocument50 pagesCognitive Therapy of Affective Disorders. BeckFrescura10% (1)

- Cognitive Therapy Offers New Hope for SchizophreniaDocument10 pagesCognitive Therapy Offers New Hope for SchizophreniaMaria Fabiola Pachano PalaciosNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of Group Sociotherapeutic Work With Elements of Psychodrama With Torture VictimsDocument9 pagesCharacteristics of Group Sociotherapeutic Work With Elements of Psychodrama With Torture VictimsElena A. LupescuNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Emotional and Social Processes in PsychosisDocument8 pagesCognitive Emotional and Social Processes in Psychosishelen.ashton5No ratings yet

- Multisensory_Stimulation_for_Elderly_WitDocument5 pagesMultisensory_Stimulation_for_Elderly_WitslyvesterNo ratings yet

- Dolan 1996Document7 pagesDolan 1996Ainia TaufiqaNo ratings yet

- Can Cognitive Deficits Explain Differential Sensitivity To Life Events in Psychosis?Document7 pagesCan Cognitive Deficits Explain Differential Sensitivity To Life Events in Psychosis?奚浩然No ratings yet

- Bourvis Et Al-2017-Frontiers in PsychologyDocument13 pagesBourvis Et Al-2017-Frontiers in Psychologyioanaciocea87No ratings yet

- DBT For PTSD Related To Childhood Sexual AbuseDocument5 pagesDBT For PTSD Related To Childhood Sexual Abusecameronanddianne3785No ratings yet

- The Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous As An Adjunctive Treatment For Trauma Survivors An Experimental Approach 1522 4821 16 120Document3 pagesThe Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous As An Adjunctive Treatment For Trauma Survivors An Experimental Approach 1522 4821 16 120gpaul44No ratings yet

- Interpersonal Psychotherapy For Depressed Adolescents (IPT-A)Document8 pagesInterpersonal Psychotherapy For Depressed Adolescents (IPT-A)Wiwin Apsari WahyuniNo ratings yet

- Conrad - 1975 - The Discovery of Hyperkinesis - Society For The Study of Social ProblemsDocument11 pagesConrad - 1975 - The Discovery of Hyperkinesis - Society For The Study of Social ProblemsLais ArendNo ratings yet

- A CritiqueDocument9 pagesA Critiquewangarichristine12No ratings yet

- Transference Focused Psychotherapy Training During Residency An Aide To Learning Psychodynamic PsychotherapyDocument22 pagesTransference Focused Psychotherapy Training During Residency An Aide To Learning Psychodynamic PsychotherapyLíaNo ratings yet

- Schizo 3Document11 pagesSchizo 3Aldy GeriNo ratings yet

- Effects of Self-Compassion DepressionDocument8 pagesEffects of Self-Compassion DepressionBelfacinoNo ratings yet

- Robert: Psychological ReportsDocument15 pagesRobert: Psychological ReportsIcaro De Almeida VieiraNo ratings yet

- Hypnosis in Post-Abortion Distress: An Experimental Case Study Valerie J. Walters and David A. OakleyDocument15 pagesHypnosis in Post-Abortion Distress: An Experimental Case Study Valerie J. Walters and David A. Oakleyanon_956649193No ratings yet

- Therapeutic Factors in Two Forms of Inpa PDFDocument12 pagesTherapeutic Factors in Two Forms of Inpa PDFTasos TravasarosNo ratings yet

- Battery TestsDocument40 pagesBattery TestsStratiatella Faith Anthony100% (1)

- Psychotherapy of Personality DisordersDocument6 pagesPsychotherapy of Personality DisordersÁngela María Páez BuitragoNo ratings yet

- ENERGY PSYCH THERAPY EVIDENCEDocument19 pagesENERGY PSYCH THERAPY EVIDENCElandburender100% (1)

- Emotional Reactivity To Daily Events in Major and Minor DepressionDocument14 pagesEmotional Reactivity To Daily Events in Major and Minor DepressionПламен ПетковNo ratings yet

- Somatoform 1Document6 pagesSomatoform 1Dewina Dyani Rosari IINo ratings yet

- Special ArticlesDocument9 pagesSpecial ArticlesLuis PonceNo ratings yet

- Fedor Off 2001Document14 pagesFedor Off 2001Gustavo PaniaguaNo ratings yet

- Depression and Psychodynamic PsychotherapyDocument5 pagesDepression and Psychodynamic PsychotherapyRija ChoudhryNo ratings yet

- The Effects of A Reality Therapy Program For The Elderly With Depressive Disorder - Ko.enDocument8 pagesThe Effects of A Reality Therapy Program For The Elderly With Depressive Disorder - Ko.enTroy CabrillasNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 934 938Document5 pagesJurnal 934 938dayuNo ratings yet

- Stigma's Impact on Psychosis Recovery Mediated by Self-Esteem, HopelessnessDocument9 pagesStigma's Impact on Psychosis Recovery Mediated by Self-Esteem, HopelessnessAmina LabiadhNo ratings yet

- Rapid Core Healing Pathways to Growth and Emotional Healing :: Using the Unique Dual approach of Family Constellations and Emotional Mind Integration for personal and systemic healthFrom EverandRapid Core Healing Pathways to Growth and Emotional Healing :: Using the Unique Dual approach of Family Constellations and Emotional Mind Integration for personal and systemic healthNo ratings yet

- Application of Derivative ReviewDocument2 pagesApplication of Derivative ReviewbpregerNo ratings yet

- Learner Statistics ProjectDocument2 pagesLearner Statistics ProjectbpregerNo ratings yet

- Yarone LetterDocument1 pageYarone LetterbpregerNo ratings yet

- Functional Behavior AssessmentDocument17 pagesFunctional Behavior AssessmentbpregerNo ratings yet

- Ap Wor S1 04 24 GaDocument2 pagesAp Wor S1 04 24 GabpregerNo ratings yet

- Los Angeles County 2020 Affordable Housing Needs Report: Key FindingsDocument4 pagesLos Angeles County 2020 Affordable Housing Needs Report: Key FindingsbpregerNo ratings yet

- Bassianus BackstoryDocument1 pageBassianus BackstorybpregerNo ratings yet

- Rekkenmark YaroneDocument1 pageRekkenmark YaronebpregerNo ratings yet

- BrahppDocument1 pageBrahppbpregerNo ratings yet

- SkinnersBehaviorismSomeFundamentalsofB F 92Document15 pagesSkinnersBehaviorismSomeFundamentalsofB F 92Daniel CelisNo ratings yet

- Example Information Sheet and Consent Form (University of Edinburgh PREC)Document7 pagesExample Information Sheet and Consent Form (University of Edinburgh PREC)bpreger100% (1)

- House RulesDocument1 pageHouse RulesbpregerNo ratings yet

- SkinnersBehaviorismSomeFundamentalsofB F 92Document15 pagesSkinnersBehaviorismSomeFundamentalsofB F 92Daniel CelisNo ratings yet

- Ap Wor S1 03 02 GaDocument2 pagesAp Wor S1 03 02 GabpregerNo ratings yet

- The Place of Community in Social Work Practice Research: Conceptual and Methodological DevelopmentsDocument36 pagesThe Place of Community in Social Work Practice Research: Conceptual and Methodological DevelopmentsbpregerNo ratings yet

- Totems of The Dead Players Guide To The Untamed Lands (8189174)Document161 pagesTotems of The Dead Players Guide To The Untamed Lands (8189174)bpreger100% (7)

- Adventure DeckDocument13 pagesAdventure Deckminininja1475No ratings yet

- Becoming A Better Math TutorDocument145 pagesBecoming A Better Math Tutorpdizzle123No ratings yet

- MDMA Assisted Psychotherapy Treatment Manual Version7 19aug15 FINALDocument69 pagesMDMA Assisted Psychotherapy Treatment Manual Version7 19aug15 FINALbpregerNo ratings yet

- Realms of CthulhuDocument161 pagesRealms of CthulhuFilip Kolakovic96% (27)

- Other - FDP4400 - DD 4E - CounDocument19 pagesOther - FDP4400 - DD 4E - CounCurtis PlunkNo ratings yet

- Amelia ImputationDocument21 pagesAmelia ImputationbpregerNo ratings yet

- How To Create and Export Flow: Google's 20 Percent Time Program and It's Impact On MotivationDocument12 pagesHow To Create and Export Flow: Google's 20 Percent Time Program and It's Impact On MotivationbpregerNo ratings yet

- PsyCap QuestionnaireDocument2 pagesPsyCap Questionnairebpreger67% (3)

- Goldberg, 1990 Five FactorDocument14 pagesGoldberg, 1990 Five FactorbpregerNo ratings yet

- Machiavellianism and EvolutionDocument15 pagesMachiavellianism and EvolutionbpregerNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Intellect and OpennessDocument19 pagesThe Relationship Between Intellect and OpennessbpregerNo ratings yet

- User Manual Xiaomi Redmi Note 11S (English - 59 Pages)Document3 pagesUser Manual Xiaomi Redmi Note 11S (English - 59 Pages)Abdallah AbdallahNo ratings yet

- I CT Material ReferenceDocument96 pagesI CT Material Referencefsolomon100% (19)

- Swift C Sharp PosterDocument1 pageSwift C Sharp PosterJoshua Shalom Cherkes100% (1)

- Quantitative Analysis of Tipha's ProposalDocument5 pagesQuantitative Analysis of Tipha's ProposalmjchipocoNo ratings yet

- 201232626Document42 pages201232626The Myanmar Times100% (1)

- Introduction To Social Return On InvestmentDocument12 pagesIntroduction To Social Return On InvestmentSocial innovation in Western Australia100% (2)

- Anthony Giddens Sociology 6 TH Anthony Giddens Sociology 6 TH Editionpdf FreeDocument2 pagesAnthony Giddens Sociology 6 TH Anthony Giddens Sociology 6 TH Editionpdf FreeAnushree AyanavaNo ratings yet

- Astm C31-C31M-23Document7 pagesAstm C31-C31M-23mustafa97a141No ratings yet

- VECV Infra NormsDocument10 pagesVECV Infra Normsvikrantnair.enarchNo ratings yet

- Salerno TEACHING SOCIAL SKILLS Jan 2017Document86 pagesSalerno TEACHING SOCIAL SKILLS Jan 2017LoneWolfXelNo ratings yet

- Design and Development of Power Inverter Using Combinational Switches For Improvement of Efficiency at Light LoadsDocument3 pagesDesign and Development of Power Inverter Using Combinational Switches For Improvement of Efficiency at Light LoadsEditor IJRITCCNo ratings yet

- Resume Updated Format 2013Document6 pagesResume Updated Format 2013afiwfrvtf100% (2)

- Debian Reference - enDocument261 pagesDebian Reference - enAa AaNo ratings yet

- Vitamins, Minerals Plus Iron, Iodine, Taurine, and Zinc: Nutrition InformationDocument1 pageVitamins, Minerals Plus Iron, Iodine, Taurine, and Zinc: Nutrition InformationWonder PsychNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan: Freedom SongsDocument3 pagesLesson Plan: Freedom SongsAllison Lynné ArcherNo ratings yet

- Party Event Planner Services ProposalDocument7 pagesParty Event Planner Services ProposalAnton KenshuseiNo ratings yet

- Johann Sebastian Bach Raaf Hekkema: Suites BWV 1007-1012Document22 pagesJohann Sebastian Bach Raaf Hekkema: Suites BWV 1007-1012Stanislav DimNo ratings yet

- Managerial Accounting InsightsDocument147 pagesManagerial Accounting InsightsSiddhantSinghNo ratings yet

- Ajumose Mag Jan-March 2013Document24 pagesAjumose Mag Jan-March 2013AJUMOSETheNewsletterNo ratings yet

- Increasing Online Buying Intention-Adult Pshycology Based: AbstractDocument5 pagesIncreasing Online Buying Intention-Adult Pshycology Based: AbstractannamyemNo ratings yet

- FCE Reading and Use of English Practice Test 5 - 1st PartDocument3 pagesFCE Reading and Use of English Practice Test 5 - 1st PartFrederico Coelho de MeloNo ratings yet

- Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Vol. 62 / No. 18Document32 pagesMorbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Vol. 62 / No. 18Southern California Public RadioNo ratings yet

- #SocializingheritageDocument38 pages#SocializingheritageMiguel A. González LópezNo ratings yet

- The Joy of Living Dangerously PDFDocument4 pagesThe Joy of Living Dangerously PDFMax MoralesNo ratings yet

- Chap 2 Self and Personality 1Document77 pagesChap 2 Self and Personality 1jiyanshi yadavNo ratings yet

- Oliveboard Seaports Airports of India Banking Government Exam Ebook 2017Document8 pagesOliveboard Seaports Airports of India Banking Government Exam Ebook 2017samarjeetNo ratings yet

- Cekungan Tomori Dan SalawatiDocument17 pagesCekungan Tomori Dan SalawatiDimas WijayaNo ratings yet

- Strength Vision Diversity Team: VF CorporationDocument55 pagesStrength Vision Diversity Team: VF Corporationmanisha_jha_11No ratings yet

- BPCL Annual Report 2010Document172 pagesBPCL Annual Report 2010Chandra MouliNo ratings yet

- BOQ For Mr. Selhading With Out Price 2Document141 pagesBOQ For Mr. Selhading With Out Price 2Mingizem KassahunNo ratings yet