Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Physician Agency

Uploaded by

Andrea Mae SanchezCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Physician Agency

Uploaded by

Andrea Mae SanchezCopyright:

Available Formats

Physician Agency:

How do physicians influence the medical services used by patients?

***In neoclassical theory, the firm sets price and quantity in order to maximize profit subject to

the constraint of market demand. Every phrase in this paradigm has been questioned when it is

applied to physician-firms.

1. Do physicians maximize profit?

Many have argued that physicians are motivated differently than other business people, that

they are, for example, concerned for their patients health, and make different tradeoffs

when it comes to their own gain or the utility of their patient-customers.

2. Are physicians constrained by market demand?

Physicians are said to work at an advantage in relation to their customers because of their

superior knowledge of the patients medical condition and of what treatments are likely to be

most helpful. According to this argument, physicians behave differently because they may

exercise market power in ways inaccessible to other sellers, controlling, not being

constrained by, patients demand.

3. Do physicians even set price and quantity?

Ubiquitous third party payers (an entity, other than the health care provider, that reimburses

and manages health care expenses) set prices to patients through terms of coverage and to

physicians through terms of reimbursement. Managed care plans seek to impose their will

on physicians decisions about treatment. In light of these complications, it is not surprising

that doctors and patients are not a ready application of neoclassical economic theory.

Using currently available textbooks as a point of reference, there is no consensus about an

alternative approach to physicianpatient interaction. Some texts present no model at all.

Among the texts committing to a model, no model or approach garners more than one vote from

the electorate of authors. And no text uses a model as a general way of organizing the

discussion of physician behavior

In a patients contact with the doctor, the doctors position is not, here is the price of my

services, how many do you want? It is more like, here is what you should do. Physicians set

quantity, and more generally, the treatment patients should use, and may make this decision in

light of the factors affecting them. Empirical studies [e.g., Gaynor and Gertler (1995)] find that

when normal demand-side variables, such as demand-price, income, and clinical need are

controlled for, variables affecting the supply of care, such as supply price, physician attitudes, or

partnership incentives, influence what happens to the patient. How is this to be understood?

Physicians induce demand: The physician-induced demand (PID) hypothesis,

associated with Evans (1974), is essentially that physicians engage in some persuasive

activity to shift the patients demand curve in or out according to the physicians self-

interest. Patients have incomplete information about their condition, and may be

vulnerable to this advertising-like activity.

- The economic theory of physician behavior has emphasized contracting and

information issues. Economists have recognized for a long time that a significant

market is missing in the health sector: payments or insurance based on health

outcomes.

- Some elements of treatment are not reported. Insurance coverage and provider

payment are based on reports of measures such as number of visits or days in

the hospital, or accounting costs, which only partially reveal the resources devoted

to treatment

- A physician or other health care provider must be relied upon to prescribe the clinical

content of the services connected with a visit or a day, and to invest (costly) effort

into making these services productive in terms of the patients health. Thus, the

physician almost always supplies her own input into the production of health care for

the patient. This input, which is often referred to as effort, but also could be

understood as quality, is simply not contractible; the market for insurance and

payment policies based on the physicians effort is also missing.

Medical Education as an Investment

- A demand and supply framework can be used to address whether the limited supply

of physicians has protected physician incomes and generated rents

- If medical school tuition were set at cost, this in itself would be prima facie evidence

for a restriction on entry leading to rents.

- The number of physicians could be at the competitive level, but the cost of training is

subsidized, perhaps to enable medical schools to collectively choose a pool of new

physicians with desirable social characteristics (high quality, ethnic diversity, social

consciousness, geographic distribution).

- The number of places at medical schools is set by administrative policy. Tuition is

subsidized. We observe then an excess demand at the subsidized price. If there

were no subsidy, the number of places demanded would be less than are demanded

at the subsidized price. It is impossible to tell if the quantity demanded at the full

price is more or less than the regulated quantity.

- A large number of empirical studies have looked at the question of entry restriction,

attempting to measure any excess return on the students investment in medical

education. In an era before federal subsidy of medical education, Friedman and

Kuznets (1954) found evidence of monopoly returns that they attributed to AMA

restrictions on entry. The presence of a tuition subsidy for medical schools (which

does not generally exist for law or business schools) implies that, if supply were

restricted to the competitive level, even the marginal physician would enjoy rents

(equal to the subsidy see Figure 1). More recent studies which evaluate the return

to tuition investment contend with evaluating students opportunity costs and

correcting for physicians long hours, without a clear finding of excess return due to

entry restrictions in medicine [see, e.g., Sloan (1970), Leffler (1978), Marder et al.

(1988)]. Weeks et al. (1994), for example, studied the return to education for

physicians, lawyers, dentists, and MBAs, and found post-high school rates of return

of 2025% for all groups

It seems very plausible that during the first half of this century, restrictions on the output of

medical schools elevated physicians economic position. When supply is constant and demand

increases a lot, sellers benefit.

(Different source)

- Net present value (NPV) is the best way to estimate the value of an investment

decision. The NPV for a medical education is positive at an annual cost of

attendance ranging from $10,000 to $100,000

- Another method to analyze investment decisions is the payback period; how long it

takes to recover the upfront costs. This is simple but ignores the time value of money

- The time-cost of money trumps everything else, because all costs of a medical

education are paid in cash up front. There is no return on this investment during

medical school and minimal return during clinical training. It is only after a physician

finishes training that the investment can be recouped.

- Tuition makes little difference on the timing of when the investment is recouped.

Private school tuition is 55% higher than in-state public school tuition, yet within just

a few more years of post-training work, the private school graduate can recoup their

investment

- For example, if one starts medical school at 27 instead of 23, the loss in lifetime

earnings is $1,000,000. Using data from 2003-2004, Dorsey showed that shortening

medical school by 1 year increased the NPV of a medical education by $160,000-

$230,000, with the majority of this due to earlier realization of the income of a

practicing physician. They also found that shortening residency training by 1 year

generates a financial benefit of $170,000. These effects are not mutually exclusive

but in fact additive.

Reference:

Doroghazi, R., & Alpert, J. (2014). A medical education as an investment: Financial food for thought. The American

Journal of Medicine. 127, 7-11. Retrieved from http:// dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.08.004

Cuyler, A., & Newhouse, J. (2000). Handbook of Health Economics. Retrieved from http://kie.vse.cz/wp-

content/uploads/Handbook_of_Health_Economics__Volume_1A.pdf

You might also like

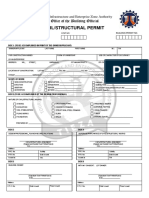

- Civil-Structural-Permit BACK-2Document1 pageCivil-Structural-Permit BACK-2Andrea Mae SanchezNo ratings yet

- Loads As Per NSCP 2015Document3 pagesLoads As Per NSCP 2015Andrea Mae Sanchez100% (1)

- 312217807-NSCP-design-Response-Spectra SDDocument2 pages312217807-NSCP-design-Response-Spectra SDAndrea Mae SanchezNo ratings yet

- Electrical Permit PDFDocument2 pagesElectrical Permit PDFYasmin75% (4)

- Graduate School - Admission TestDocument3 pagesGraduate School - Admission TestAndrea Mae SanchezNo ratings yet

- Pallitive Unit Nursing Committee Monitoring of Existing Plans and ProjectsDocument2 pagesPallitive Unit Nursing Committee Monitoring of Existing Plans and ProjectsAndrea Mae SanchezNo ratings yet

- Civil-Structural-Permit BACKDocument2 pagesCivil-Structural-Permit BACKAndrea Mae Sanchez100% (1)

- BGHMC List of Remaining WorksDocument2 pagesBGHMC List of Remaining WorksAndrea Mae SanchezNo ratings yet

- CF3 CF4: Column Schedule Footing ScheduleDocument1 pageCF3 CF4: Column Schedule Footing ScheduleAndrea Mae SanchezNo ratings yet

- Midterm Assignment 1: Solutions and Answers HereDocument1 pageMidterm Assignment 1: Solutions and Answers HereAndrea Mae SanchezNo ratings yet

- Peri Accessories For BayombongDocument3 pagesPeri Accessories For BayombongAndrea Mae SanchezNo ratings yet

- Calendar of ActivitiesDocument9 pagesCalendar of ActivitiesAndrea Mae SanchezNo ratings yet

- Final-Exam TEST LANGDocument1 pageFinal-Exam TEST LANGAndrea Mae SanchezNo ratings yet

- Folder HeadingsDocument1 pageFolder HeadingsAndrea Mae SanchezNo ratings yet

- Icfs Proposal SPCDocument1 pageIcfs Proposal SPCAndrea Mae SanchezNo ratings yet

- Fencing Plan: Private Access RDDocument1 pageFencing Plan: Private Access RDAndrea Mae SanchezNo ratings yet

- For BackloadDocument1 pageFor BackloadAndrea Mae SanchezNo ratings yet

- Existing Riprap: Cyclone WireDocument1 pageExisting Riprap: Cyclone WireAndrea Mae SanchezNo ratings yet

- Fencing Estimate - Cyclone WiresDocument1 pageFencing Estimate - Cyclone WiresAndrea Mae SanchezNo ratings yet

- Itablestructural For PrintingDocument2 pagesItablestructural For PrintingAndrea Mae SanchezNo ratings yet

- Vicinity Map: LOT 4-A-3-F-1Document1 pageVicinity Map: LOT 4-A-3-F-1Andrea Mae SanchezNo ratings yet

- For Fencing PermitDocument2 pagesFor Fencing PermitAndrea Mae SanchezNo ratings yet

- General Structural Notes: Wall Intersection DetailDocument1 pageGeneral Structural Notes: Wall Intersection DetailAndrea Mae SanchezNo ratings yet

- EARTHQUAKE ENGINEERING - Midterm ExamDocument33 pagesEARTHQUAKE ENGINEERING - Midterm ExamAndrea Mae SanchezNo ratings yet

- Pre-Stressed Concrete MSCE 514: Problem Set 2Document8 pagesPre-Stressed Concrete MSCE 514: Problem Set 2Andrea Mae Sanchez0% (1)

- Earthquake Engineering MSCE 510: Problem Set 3Document4 pagesEarthquake Engineering MSCE 510: Problem Set 3Andrea Mae SanchezNo ratings yet

- Estimate SampleDocument1 pageEstimate SampleAndrea Mae SanchezNo ratings yet

- MSCE 510 Ps 2Document3 pagesMSCE 510 Ps 2Andrea Mae SanchezNo ratings yet

- MSCE 510 Ps 2Document3 pagesMSCE 510 Ps 2Andrea Mae SanchezNo ratings yet

- S14062 Wire and Strand Brochure - Construction ProductsDocument24 pagesS14062 Wire and Strand Brochure - Construction ProductsMohammed Abdulwajid Siddiqui100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Colegio Tecnico Profesional Santo DomingoDocument3 pagesColegio Tecnico Profesional Santo DomingoStaling BFloresNo ratings yet

- John Rawls A Theory of JusticeDocument2 pagesJohn Rawls A Theory of JusticemartinNo ratings yet

- Labor Economics ManualDocument97 pagesLabor Economics ManualLam Wai Kuen100% (3)

- 022482-2508a Sps855 Gnss Modular Receiver Ds 0513 LRDocument2 pages022482-2508a Sps855 Gnss Modular Receiver Ds 0513 LRJames Earl CubillasNo ratings yet

- 2023 Occ 1ST ExamDocument3 pages2023 Occ 1ST ExamSamantha LaboNo ratings yet

- General Awareness Questions Asked CGL17 - 10 PDFDocument13 pagesGeneral Awareness Questions Asked CGL17 - 10 PDFKishorMehtaNo ratings yet

- The Use of Mathematica in Control Engineering: Neil Munro Control Systems Centre Umist Manchester, EnglandDocument68 pagesThe Use of Mathematica in Control Engineering: Neil Munro Control Systems Centre Umist Manchester, EnglandBalaji SevuruNo ratings yet

- Females Working in A Male Dominated PositionDocument14 pagesFemales Working in A Male Dominated PositionAlexis DeCiccaNo ratings yet

- Recovering The Essence in Language - EssayDocument3 pagesRecovering The Essence in Language - EssayOnel1No ratings yet

- Outlook Errors & SMTP ListDocument19 pagesOutlook Errors & SMTP Listdixityog0% (1)

- Venue and Timetabling Details Form: Simmonsralph@yahoo - Co.inDocument3 pagesVenue and Timetabling Details Form: Simmonsralph@yahoo - Co.inCentre Exam Manager VoiceNo ratings yet

- Insat 3d BrochureDocument6 pagesInsat 3d BrochureNambi HarishNo ratings yet

- Diagnosing Borderline Personality DisorderDocument12 pagesDiagnosing Borderline Personality DisorderAnonymous 0uCHZz72vwNo ratings yet

- Aashto T 99 (Method)Document4 pagesAashto T 99 (Method)이동욱100% (1)

- Correction Factor PET PDFDocument6 pagesCorrection Factor PET PDFAnonymous NKvozome5No ratings yet

- Quiz in STSDocument2 pagesQuiz in STSGeron PallananNo ratings yet

- Autism Awareness Carousel Project ProposalDocument5 pagesAutism Awareness Carousel Project ProposalMargaret Franklin100% (1)

- 220-229 Muhammad Hilal SudarbiDocument10 pages220-229 Muhammad Hilal SudarbiMuh Hilal Sudarbi NewNo ratings yet

- Mfuzzgui PDFDocument7 pagesMfuzzgui PDFMohammad RofiiNo ratings yet

- Component Object ModelDocument13 pagesComponent Object ModelY.NikhilNo ratings yet

- Eular Beam FailureDocument24 pagesEular Beam FailureSaptarshi BasuNo ratings yet

- Rubric For Talk ShowDocument1 pageRubric For Talk ShowRN Anunciacion100% (2)

- Physics of CheerleadingDocument1 pagePhysics of CheerleadingMarniella BeridoNo ratings yet

- Studio D A1 WorkbookDocument4 pagesStudio D A1 WorkbookZubyr Bhatty0% (1)

- 1735 - Alexander Pope - Works Vol IDocument244 pages1735 - Alexander Pope - Works Vol IMennatallah M.Salah El DinNo ratings yet

- Linear Equations and Inequalities in One VariableDocument32 pagesLinear Equations and Inequalities in One VariableKasia Kale SevillaNo ratings yet

- Alfredo Espin1Document10 pagesAlfredo Espin1Ciber Genesis Rosario de MoraNo ratings yet

- Training: A Project Report ON & Development Process at Dabur India LimitedDocument83 pagesTraining: A Project Report ON & Development Process at Dabur India LimitedVARUN COMPUTERSNo ratings yet

- The SophistsDocument16 pagesThe SophistsWella Wella Wella100% (1)

- PP-12-RIBA 4 ChecklistDocument6 pagesPP-12-RIBA 4 ChecklistKumar SaurabhNo ratings yet