Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sustainable Community Development Code Beta Version 1.2

Uploaded by

bcap-oceanCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sustainable Community Development Code Beta Version 1.2

Uploaded by

bcap-oceanCopyright:

Available Formats

Sustainable Community Development Code

A Code for the 21st Century

Beta Version 1.2 Revised: 1-30-09

Sustainable Community Development Code Beta version 1.2 1

Sustainable Community Development

Code Approach

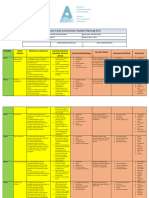

The sustainable community development code framework is sustainable at its core,

multi-disciplinary in its approach, and contextually oriented. It fully encompasses

environmental, economic, and social equity. It is innovative and distinctive by linking

Because a community is, by definition, placed,

natural and man-made systems, incorporating useful features of other zoning systems,

its success cannot be divided from the success of its place....

for example, performance and form based, and responds to regional climate, ecology,

its soil, forests, grasslands, plants and animals, water, light, and air.

and culture.

The two economies, the natural and the human, support each other;

each is the other's hope of a durable and livable life. The basic organization and approach to each topic is to examine relevant obstacles,

incentives, and regulations. The first row of every topic identifies obstacles to

--Wendell Berry achieving stated goals that might be found in a zoning code, for example, bans on

solar panels as accessory uses. The second row suggests incentives that might be

created to achieve a goal, for example, increased density in a multi-family

development that installs green roofs. The third focuses on regulations that might be

adopted to ensure progress in a particular area, for example, mandatory water-

conserving landscape standards.

Each row is divided into five columns. The first three columns suggest levels of effort

for the three basic approaches noted above. For example, a good (bronze) level of

effort in removing obstacles to small-scale wind turbines might be removing height

limits on accessory structures in some residential districts. Up the scale, a silver level

might be to prohibit private covenants in subdivisions that do not allow small-scale

wind turbines. The highest level of effort (gold) could allow wind-turbines as a by-right

use in many zone districts subject to specific performance standards related to issues

such as noise. The fourth and fifth columns in each section provide key references

and code examples/citation with hyperlinks.

Sustainable Community Development Code Beta version 1.2 2

4.2.1. Complete Streets

Table of Contents 4.2.2. Bicycle Mobility Systems

4.2.3. Pedestrian Mobility Systems

The topics covered in the Sustainable Community Development Code are listed below.

4.2.4. Public Transit

Chapters currently available are highlighted in blue. New chapters will be available soon.

Other topics are under consideration. Background research monologues have been 4.3. Parking

prepared for many of these topics and are available online at www.law.du.edu/rmlui. Work

is continuing on individual sections. 5. COMMUNITY

5.1. Community Development (forthcoming)

1. ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH AND NATURAL RESOURCES 5.2. Public Participation and Community Benefits

1.1. Climate Change

1.2. Low Impact Development and Green Infrastructure 6. HEALTHY NEIGHBORHOODS, HOUSING, FOOD SECURITY

1.3. Natural Resource Conservation/Sensitive Lands Protection (forthcoming) 6.1. Community Health and Safety

1.4. Water Conservation 6.2. Affordable Housing

1.5. Solid waste and recycling (forthcoming) 6.3. Housing Diversity and Accessibility

6.4. Food Production and Security

2. NATURAL HAZARDS

7. ENERGY

2.1. Floodplain Management (forthcoming)

2.2. Wildfires in the Wildland-Urban Interface 7.1. Renewable Energy: Wind (small- and large-scale)

2.3. Coastal Hazards 7.2. Renewable Energy: Solar (including solar access)

2.4. Steep Slopes (forthcoming) 7.3. Energy Efficiency and Conservation (forthcoming)

8. LIVABILITY

3. LAND USE AND COMMUNITY CHARACTER

8.1. Noise (forthcoming)

3.1. Character and Aesthetics (forthcoming)

8.2. Lighting (forthcoming)

3.2. Urban Form and Density (forthcoming)

8.3. Visual Elements

3.3. Historic Preservation (forthcoming)

4. MOBILITY & TRANSPORTATION

4.1. Transit Oriented Development

4.2. Mobility Systems

Sustainable Community Development Code Beta version 1.2 3

Acknowledgements

OTHER CONTRIBUTORS (IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER)

A very special thank you to all of those individuals and organizations that have Eric Bergman, Tom Boone, Michael Buchenau, Lisa Buckley, Lisa Burke,

participated by freely giving their time and talent to this endeavor: Federico Cheever, Tom Clark, Jeffrey Conklin, Michelle DeLaria, Jeremy Klop,

Robin Kniech, Jim Lindberg, Jill Litt, Chuck Luna, David Mallory, Michael

PRIMARY AUTHORS & RESEARCH ASSISTANTS AND THEIR

McCormick, Carol McLennan, Heather McLeod, Chris Nevitt, Doug Plasencia,

CHAPTERS Peter Pollock, John Powers, David Riddle, Randall Rutsch, Fahiyre Sancar,

David Schaller, Ron Stimmel, Elizabeth Tallent, Ed Thomas, Jamie Thompson,

• Bill Collins, Bill Collins Associates: Visual Elements Bud Watson, Morey Wolfson.

• Lyndsey Crum, University of Denver Sturm College of Law: Parking

• Michelle Delaria, Denver Urban Drainage District: Low Impact

Development/Green Infrastructure

ORGANIZATIONS

• Chris Duerksen, Clarion Associates: Climate Change Association of State Floodplain Managers, AWARE Colorado, Bill Collins

• Erica Heller, Clarion Associates: Renewable Energy: Wind Power Associates, Colorado Office of Smart Growth, Denver Regional Council of

• Jeff Hirt, Clarion Associates: Community Health and Safety Governments, Denver Urban Gardens, Clarion Associates, PMC (California),

• Joe Holmes, RMLUI: Parking, Transit Oriented Development University of Denver Sturm College of Law, Colorado Center for Sustainable

• Amy Kacala, Clarion Associates: Water Conservation Urbanism (University of Colorado), Meza Construction, Civic Results, Douglas

• Leigh-Anne King, Clarion Associates: Housing Diversity and Accessibility, County, Fehr & Peers Transportation Consultants, City of Boulder, City of

Affordable Housing Aurora, Front Range Economic Strategy Center, National Trust for Historic

• Jeremy Klop, Fehr & Peers: Complete Streets

Preservation, University of Colorado School of Medicine, EDAW, Urban

• Molly Mowery, Clarion Associates: Natural Hazards: Wildfire

• Cynthia Peterson, AWARE Colorado: Low Impact Development/Green

Drainage & Flood Control District, Tri-County Health Department, Rocky

Infrastructure Mountain Land Use Institute, Denver City Council, Michael Baker

• Craig Richardson, Clarion Associates: Natural Hazards: Coastal Jr.(Massachusetts and Arizona), Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Alliance for a

• Randall Rutsch, City of Boulder: Public Transit Sustainable Colorado, City of Boulder, US Environmental Protection Agency,

• Jamie Scubelek, Erasmus University: Pedestrian and Bicycling Systems Model Forest Policy Program (Maryland), Colorado Governor's Energy Office.

• Libby Tart-Schoenfelder, City of Aurora Planning Department: Transit

Oriented Development

• James Van Hemert, RMLUI: Food Production and Security, Public

Participation & Community Benefits

• Bob Watkins, City of Aurora Planning Department: Transit Oriented

Development

• Darcie White, Clarion Associates: Renewable Energy: Solar Access

Sustainable Community Development Code Beta version 1.2 4

Climate Change and

Greenhouse Gas Reduction

Revised 1-28-09

INTRODUCTION

Global warming is being accepted as a fact of life in most quarters. Tangible evidence seems to be accumulating on an

almost daily basis—shorter winters, melting polar ice caps, rising sea levels, and deeper droughts. Greenhouse gasses

are increasingly linked to global warming and are seen as a primary culprit.

Greenhouse gases are made up of carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxides. They contribute to global warming by

trapping radiation from the sun. The bulk of greenhouse gases emitted in the United States is associated with

transportation (e.g., cars) and energy generation and usage.

IMPLICATIONS OF NOT ADDRESSING THE ISSUE

If current low-density, “sprawl” development patterns in many communities continue and expand, the ability to reduce

VMTs in the future will be seriously hamstrung. Once development patterns are set, it is exceedingly difficult to affect

travel patterns and preferences. Low-density development makes cost-effective mass transit nearly impossible.

The same is true with preservation of mature trees that absorb huge quantities of greenhouse gases and sequester

them for many years. If mature trees are needlessly cut to accommodate new development rather than new

development being shaped to preserve these trees whenever possible, their destruction will actually release stored

greenhouse gases (through burning or rotting), and it will take decades to replace them with smaller trees that absorb

much less carbon dioxide in their early years.

Additionally, if communities do not take steps to accommodate and encourage alternative energy sources such as wind

and solar, development patterns may be set that prohibit retrofitting in the future.

THE ROLE OF LAND USE REGULATIONS IN CONTROLLING

GREENHOUSE GAS GENERATION

Land-use and zoning regulations can thus play an important role in helping to reduce greenhouse gas emissions

through:

Encouraging development patterns that allow less reliance on autos for mobility and result in reduction in

vehicle miles traveled and corresponding greenhouse gas emissions

Preserving existing trees that can sequester carbon dioxide and require the planting of new trees

Promoting alternative energy generation such as solar and wind power that do not generate greenhouse

gases as do oil, gas, and coal-fired power plant

Sustainable Community Development Code Beta version 1.2 5

DRAFT Sustainable Community Development Code Framework

CLIMATE CHANGE

KEY STATISTICS AND FACTS:

Greenhouse gases include carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxides.

The United States, with 4% of the world’s population, emits almost 25% of global carbon dioxide each year—second only to China. Carbon emissions in the U.S. have increased about 20% since 1990

In the U.S., each person’s direct emissions amount to 40% of this total—mostly from household energy and transportation. Total per person carbon emissions are about 16.5 metric tons (11.0 home; 5.00 auto; .5 air travel). 60% of transportation emissions

come from fueling and driving autos.

The average mid-size car emits 9.500 pounds of carbon dioxide annually

In the U.S., development is becoming more spread out--land consumed for development has increased at a rate of twice that of population growth between 1982 and 2002. During that period, per capita vehicle miles traveled (VMT) increased three times

population growth

According to a study of 83 metro areas by Reid Ewing, residents in compact regions (Boston, Portland) drove about 25% less than those in sprawling regions (Atlanta, Raleigh)

Residents in the most walkable neighborhoods drive 26 fewer miles per day than those in the most sprawling areas according to a report conducted in King County, Washington, by Larry Frank. A study for the City of Sacramento, CA, reported that a compact

growth scenario would result in a 25% reduction in VMT per house per day

According to a study by Ewing, a doubling of development density can reduce VMTs by 5%. Other studies report a 5-15% reduction in VMT associated with mixed-use projects

According to the Dept. of Energy, a 30-year old hardwood tree can sequester the equivalent of 136 pounds of carbon dioxide annually. About 70 such trees would offset the carbon dioxide emissions from one medium-size car

Planting a hectare of riparian forest can over the next 100 years offset the carbon emissions caused by 54,000 gallons of gasoline

Net carbon sequestration by forests, urban trees, and agriculture can offset 15% of total U.S. carbon dioxide emissions annually

CLIMATE CHANGE AND GREENHOUSE GAS REDUCTION

Achievement Levels (Note: higher levels generally incorporate or exceed actions of lower levels)

Bronze (Good) Silver (Better) Gold (Best) References/Commentary Code Examples/Citations

Remove Allow mixed-use development by Allow larger recycling facilities in Require all single-family See .org for tools for protecting Colorado Springs Mixed-Use

Obstacles right in selected zone districts appropriate industrial and developments to include trees and urban forests Development Manual,

Permit solar and small wind commercial zone districts minimum % of accessory units T. Litman, Parking Management ://www.springsgov.com/units/plann

0 turbines by right in selected zone Reduce parking requirements for Prohibit single-use Best Practices, American ing/Currentproj/CompPlan/MixedUs

districts (See Renewable Energy mixed-use developments/in developments/buildings in Planning Association. 2006 eDev/I.pdf

Section (solar access and wind mixed-use districts commercial zone districts See Smart Code mixed-use Santa Cruz, CA – accessory

power) of Code framework for Tailor development standards (e.g., downtown) (transect) districts at dwelling unit program

citations) (e.g., landscaping, open space, Prohibit urban level ://www.smartcodecentral.org/ ://www.ci.santa-

Allow accessory units and parking) to encourage infill and development (e.g., more than cruz.ca.us/pl/hcd/ADU/adu.html.

US Department of Energy

live/work units by right in mixed-use development (e.g., 1 residential unit/acre) outside See Housing Affordability Section

methodology for calculating

residential zone districts alternative open space such as defined urban service areas of Model Code for additional

carbon sequestration by trees:

plazas, community gardens, citations regarding accessory

Allow live-work units in ://ftp.eia.doe.gov/pub/oiaf/1605/c

green roofs; reduced landscaped dwelling units

commercial and mixed-use drom/pdf/sequester.pdf

districts Permit small-scale buffers with enhanced State of Oregon urban growth

recycling facilities in residential ornamental fencing) boundary regulations

zone districts Reduce overly restrictive ://www.oregon.gov/LCD/ruraldev.s

height/setback requirements for html

small-scale wind turbines

Sustainable Community Development Code Beta version 1.2 6

DRAFT Sustainable Community Development Code Framework

CLIMATE CHANGE

Achievement Levels (Note: higher levels generally incorporate or exceed actions of lower levels)

Bronze (Good) Silver (Better) Gold (Best) References/Commentary Code Examples/Citations

Create Offer density/height bonuses for Reduce transportation impact Encourage low-energy Chesapeake Bay Program urban Portland, OR, FAR bonuses for

Incentives green roofs fees for mixed-use and infill maintenance landscaping by tree canopy program ecoroofs (City zoning code 33.510:

Give bonus points for green/cool projects to reflect lower traffic giving additional landscaping ://www.dnr.state.md.us/forests/p ://www.epa.gov/hiri/resources/pdf/

roofs in commercial design generation credit rograms/urban/urbantreecanopy EcoroofsandGreenCityStrategies.p

standard point systems Create density bonus and goals.asp df

Allow and encourage shared expedited processing incentives For general information on

parking arrangements for infill and mixed-use permeable pavement, see Landscaping credit for preserving

Tree protection during developments ://www.epa.gov/owow/nps/pave existing trees:

Give priority parking for vans,

construction

Allow green roofs to qualify for ments.pdf and ://www.colleyville.com/files/Ch.%2

hybrid vehicles, and bicycles in

open space credits ://www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/per 004%20Landscaping%20and%20B

parking standards

meable_paving uffering.pdf

Give increased landscaping Offer height increases, density

bonuses, and flexibility regarding ://www.ewgateway.org/pdffiles/libr

credit for preserving existing

non-conforming use regulations ary/wrc/TB-LandscapingRegs.pdf

trees

for projects that remove Austin, Texas, Development Code:

impermeable surfaces from Subchapter E: Design Standards

existing developments or reduce and Mixed-Use, available online at

during redevelopment or use ://www.ci.austin.tx.us/development

permeable pavement /downloads/final.pdf

Enact Require sidewalks in all Require replacement of all trees Require green roofs on all University of Florida, A Guide To Aspen/Pitkin County Renewable

Standards developments and connections removed during development on commercial and multifamily Selecting Existing Vegetation For Energy Mitigation Program.

with adjacent sites an inch/inch diameter basis or developments. A Low Energy Landscapes. ://www.aspencore.org/sitepages/pi

Adopt historic preservation contribution to offsite tree fund Require low-energy online. d31.php;

standards to protect existing Enact minimum density/intensity landscaping. American Planning Assn. PAS ://www.greenpowergovs.org/Solar

structures (and energy they standards to encourage compact Report 446, Tree Conservation 4aspencode.html

Enact limitations on house size

represent) development Ordinances. Zoning Practice Boulder, Colorado, Solar Access

Adopt minimum reforestation

Limit coniferous trees on Adopt pedestrian connectivity July 2006, Tree Preservation. Regulations, available online at

requirements for sites without

southern sides of buildings in standards to reduce vehicle use For a good discussion of a http://www.bouldercolorado.gov/file

vegetation.

northern climates to preserve carbon offset measurement s/PDS/codes/solrshad.pdf

Enact solar access ordinance Establish mandatory carbon

solar access (See Renewable Energy/solar methodology, see Forest Maryland Forest Conservation

budgets/limits for new

Require planting of deciduous access section.) Guardians Carbon Offfset Act/Regulations:

developments (emissions from

trees Program Description: ://www.dnr.state.md.us/forests/pro

Require bicycle fleets for all added traffic, energy used in

://www.fguardians.org/support_d gramapps/newFCA.asp

Adopt regulations to protect hotels, resorts construction materials, future

ocs/document_carbon- Franklin, TN, connectivity 5.10.4)

larger trees Limit number of garages allowed energy requirements) and

calculation-methodology_2- and tree protection regulations

Require provision of bicycle on each residential lot (1-2 vs. 3- offsets/impact fees

07.pdf (5.3): ://www.franklin-

racks in all multifamily and 4) Require minimum % of homes

US EPA Personal Emissions gov.com/pdf/Franklin%20Zoning%

commercial developments Limit impermeable surface areas in subdivisions to be oriented

Calculator: 20Ordinance-%20Effective%201-1-

and require use of permeable for passive solar access (on

://www.epa.gov/climatechange/e 08.pdf

pavement in appropriate areas an east/west axis) (See

missions/ind_calculator.html Bicycle Level of Service Standards:

Renewable Energy/solar

Sustainable Community Development Code Beta version 1.2 7

DRAFT Sustainable Community Development Code Framework

CLIMATE CHANGE

access section.) U.S. Green Building Council, http://sf-now.com/sf-

Require outdoor signage to be LEED for Neighborhood Rating bike/SFBC_LOS_Research.pdf;

turned off when business is System (See Green Construction Florida DOT:

closed and Technology chapter.), ://www.dot.state.fl.us/planning/syst

available online at ems/sm/los/pdfs/blos-art.pdf

Require new developments to

be carbon neutral ://www.usgbc.org/DisplayPage.a Fort Collins, CO, minimum density

spx?CMSPageID=222 requirements in medium-density

mixed-use zone district:

://www.ci.fort-

collins.co.us/cityclerk/codes.php

CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION—FUTURE SECTION

Sustainable Community Development Code Beta version 1.2 8

example, excess nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorus, lead to algae blooms and a condition known as eutrophication,

which damages aquatic ecosystems. Metals and other toxic chemicals in polluted runoff negatively impact aquatic life and human

Low Impact Development/Green Infrastructure health. Finally, polluted runoff can introduce bacteria, viruses and other pathogens into local water bodies.

Revised 1-14-09

Without the application of innovative

INTRODUCTION approaches, communities will continue

On undeveloped land most precipitation filters through the soil recharging groundwater and providing base flow to nearby streams, to finance storm drainage infrastructure

ponds, wetlands, rivers and lakes. as well as capital improvement projects

to address waterway stabilization and

Land development adds impervious surfaces such as cement, asphalt, and roofing. The natural cycle is disturbed, and the amount water quality needs brought on by

of precipitation that is infiltrated decreases, while the runoff portion increases. This changes both water quantity and quality, with traditional, drainage-based

increased flood risk, pollutant loading, waterway scour and sedimentation. Low impact development (LID) and green infrastructure development. These approaches will

have emerged as techniques that can reduce the negative effects of traditional, drainage-based land development. increase financial pressures on local

governments, continue to degrade water

Low impact development (LID) is a holistic planning, design, and construction process that seeks to reduce runoff volume by quality and negatively impact the natural

infiltrating and absorbing small, frequent storms close to where runoff is generated. Green Infrastructure is a new term that is often functions of riparian corridors.

used interchangeably with LID. In fact, green infrastructure appears to be eclipsing LID and includes a broader goal of using

natural systems and functions to reduce runoff and manage stormwater.

Figure: Advanced Pavement Technology

GOALS FOR LOW IMPACT DEVELOPMENT/GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE

There are many techniques communities can use, either alone or in combination, to promote the adoption of LID or green

infrastructure approaches to land use and stormwater management. The choices made regarding these techniques are often a

reflection of the individual community’s needs and priorities.

The goal of LID and green infrastructure is to reduce the negative impacts of increased imperviousness on waterways, riparian

areas and overall water quality with the ultimate goal of having developed land function similar to undeveloped land. Communities

Fire lane Bioswale can advance this goal by:

Removing regulatory obstacles to LID/green infrastructure design

Except as otherwise noted, all photos in this chapter are provided by Michelle DeLaria, Cynthia Peterson, Joe Chaplin Providing incentives to encourage developments to use LID/green infrastructure design.

and Herman Feissner and Chuck Taylor. Contact Michelle DeLaria at mdelaria@udfcd.org for photo use. Providing opportunities for LID techniques in the public right of way.

Providing regulatory guidance on LID/green infrastructure design.

Green infrastructure also includes a concept of scale, whereas LID is typically associated with small, decentralized BMPs. For Requiring that land development design mimic pre-development hydrology.

example, green infrastructure on a large scale may be a constructed wetland that offers multiple stormwater, environmental and Requiring that redevelopment incorporate LID/green infrastructure approaches to restore pre-development hydrology

social benefits. On a small scale, green infrastructure may include a bioswale or a permeable paver system to reduce runoff and to the maximum extent practicable.

provide a site amenity.

Addressing offsite costs of drainage-based design.

Regardless of the term used or project scale, mimicking predevelopment hydrology to meet water quality and channel protection

goals using natural system functions (infiltration, absorption and evapo-transpiration) is the common objective. The best protection of our water quality, riparian corridors and waterways is the thoughtful use of land that promotes healthy

watersheds. The following code chart presents many options, from modest to aggressive, that may be used as a path to low

impact development and/or green infrastructure.

IMPLICATIONS OF NOT ADDRESSING THE ISSUE

The impacts of traditional approaches to stormwater management are present in almost every community. Scoured, downcut and

destabilized waterways are among the most visible results of added impervious area and drainage-based land development.

Furthermore, the strategy of collecting runoff in storm sewer systems and conveying it to the nearest stream or river as quickly as

possible only serves to create an “express route” for nonpoint source pollutants that can impair nearby water resources. For

Sustainable Community Development Code Beta version 1.2 9

DRAFT Sustainable Community Development Code Framework

LOW IMPACT DEVELOPMENT/GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE

Key Statistics:

Impervious area in the U.S. nearly covers an area the size of Ohio. 1

Undeveloped land naturally absorbs small, frequent storms – for example, this is about the first inch of precipitation in the Denver Front Range. 2

Undeveloped land in metro Denver, for example, has less than one runoff event a year; after development; there are 20-30 runoff events. 3

The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) is in debt approximately $20 billion to the U.S. Treasury. 4

In the St. Louis, Mo., area, more than $2.2 billion of new development has occurred on land that was underwater during the 1993 flood. 5

A 1,000 square foot rooftop will contribute almost 350 gallons of runoff from only one inch of rain. 6

Because of impervious surfaces, a typical city block generates over five times more runoff than a woodland area of the same size. 7

Narrower streets can result in a five to 20% overall reduction in impervious area for a typical residential subdivision. 8

Cluster development can reduce imperviousness by 10 percent to 50 percent compared to conventional subdivision layouts, reducing the rate and volume of runoff and the quantity of pollutants. 9

Clean Water Services (an Oregon public utility) determined that car habitat (roads, parking lots, driveways) is 54% of the impervious area in suburban land development. 10

Roads and driveways often comprise the greatest amount of impervious area in new development (Pennsylvania) - as much as 70% of the total impervious area. 11

Boulder, Colorado’s municipal trees intercept 6 million cubic feet of stormwater annually, or 1,271 gallons per tree on average. The total value of this benefit to the city is $532,311, or $14.99 per tree. 12

ACHIEVEMENT LEVELS

Bronze (Good) Silver (Better) Gold (Best) References/Commentary Code Examples/Citations

Remove • Guidelines that could be

Obstacles

Reduce parking: Provide the same review timeframe Provide engineering • National Association of Home Builders.

for LID design as drainage-based templates for infiltration and Municipal Guide to LID. Available adopted into local code: Urban

Reduce minimum off street parking Drainage Criteria Manual

standards design absorption techniques when online. Retrieved January 15, 2009.

techniques are combined, Volume 3 – Four Step Process:

• Permit shared parking Provide credit towards open space • AWARE Colorado, an initiative of the BMP Planning for New

dedication and set-aside such as grass buffers,

League of Women Voters of Colorado Development and

• Reduce minimum off-street parking if requirements for protection of bioswales, and permeable

Education Fund, provides information Redevelopment, section 1.2:

public transportation is available sensitive natural areas and wildlife pavement systems to community leaders statewide about Available online. Retrieved

Flush curb • Allow single sided parking on street habitat Provide LID site development the impacts of land use on water January 15, 2009.

Allow pervious materials for templates for residential, quality, and suggests strategies to

• Allow overnight parking in • Snohomish County Code, Low

sidewalks in accordance with commercial and industrial protect rivers, lakes and streams.

driveways and on-street in Impact Development, Section

Americans with Disabilities Act development Resources available online. Retrieved

developments that use shared 30.63C.010, go to page 550.

driveways and rear-loaded garages requirements Base fees, charges and January 15, 2009.

• Colorado Association of Stormwater http://www.co.snohomish.wa.us/

Establish street templates based on standards upon the true cost

Permit or encourage flush curbs or wheel and Floodplain Managers. , Resources Documents/Departments/Council

actual access needs of emergency of drainage-based land

stops and sumped landscape islands in available online. Retrieved January 15, /county_code/CountyCodeTitle3

equipment development to the

parking lots 2009. 0.pdf

community

Place stormwater design review early in Reduce the size of conventional • Model Ordinances to Protect

stormwater infrastructure Except in critical aquifer • ECONorthwest. The Economics of Low

Permeable paver parking lot the development review process Impact Development: A Literature Local Resources

requirements relative to the use and recharge areas, allow

Enable joint department review of Review. Available online. Retrieved http://www.epa.gov/owow/nps/or

benefits of LID/Green Infrastructure porous/permeable pavement

development plans January 15, 2009. dinance/index.htm

options for right-of-way and

Encourage property owners to adopt

Allow alternative street designs that emergency access: fire lanes, • U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

site-based LID/green infrastructure

reduce imperviousness but maintain shoulders and alley Reducing Stormwater Costs Through

practices, such as rain gardens, rain

emergency access barrels and other rainwater Update development, LID Strategies and Practices. Available

Allow alternative cul-de-sac designs that harvesting practices* building, and plumbing codes Online. Retrieved January 15, 2009.

reduce imperviousness but maintain Allow LID/green infrastructure to allow reuse of stormwater • University of Nevada. Nonpoint

emergency access and full access for techniques off-site for infill and for non-potable purposes Education for Municipal Officials

pedestrians and cyclists redevelopment areas (NEMO). Available online. Retrieved

January 15, 2009.

Sustainable Community Development Code Beta version 1.2 10

ACHIEVEMENT LEVELS

Bronze (Good) Silver (Better) Gold (Best) References/Commentary Code Examples/Citations

Prohibit private covenants that prevent University of Arizona. NEMO.

the use of LID and/or water conservation Available online. Retrieved January 15,

landscaping 2009.

Allow narrower sidewalks or sidewalks City of Seattle. Street Edge

on one side of the street as appropriate Alternatives (SEA Streets) project:

Provide predictability and transparency Available online. Retrieved January 15,

about which lands are more suitable for 2009.

development and which are a priority for Puget Sound Partnership. Puget

preservation (see chapter on Sensitive Sound Regulatory Assistance Project:

Natural Lands) Available online. Retrieved January

Permeable paver street Allow LID/Green Infrastructure facilities 15, 2009.

to count towards local open space set National Association of Home Builders.

aside requirements Builders Guide to LID: Available online.

Acknowledge trees as part of community Retrieved January 15, 2009.

infrastructure and develop a coordinated U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

design for locating public utilities to Fact Sheets & Reports,

provide enough space for mature tree Design/Guidance Manuals. Available

canopy and root development (see online. Retrieved January 15, 2009.

Structural Soil guidelines under

References) Cornell University. Cornell Structural

Soil for Urban Trees. Available online.

Green Roof Adopt streamlined permitting procedures Retrieved January 15, 2009.

for brownfield redevelopment plan review

Urban Drainage and Flood Control

Tailor standards for landscaping, District. Peak Flow Control for Full

buffering, parking, and open space areas Spectrum of Design Storms, detention

to avoid imposing suburban parking concept paper. Available online.

requirements in high-density infill areas Retrieved January 15, 2009.

Stormwater Center. Better Site Design

Fact Sheet: Narrower Residential

Streets.

www.stormwatercenter.net/Assorted%

20Fact%20Sheets/Tool4_Site_Design/

narrow_streets.htm.

Retrieved January 15, 2009.

Street bioswale

Photo: Seattle Public Utilities

Sustainable Community Development Code Beta version 1.2 11

ACHIEVEMENT LEVELS

Bronze (Good) Silver (Better) Gold (Best) References/Commentary Code Examples/Citations

Create

Provide incentives such as eliminating or Sponsor pilot demonstration projects Provide cost sharing for Mecklenburg County. Watershed - City of Sammamish. Proposed

Incentives

reducing stormwater drainage fees, providing Subsidize maintenance of LID/Green property owners to retrofit Urban Cost Share Program. Available LID Municipal Code

density credits, expediting case Infrastructure BMPs on private with runoff reduction online. Retrieved January 15, 2009. Amendments. Available online.

processing/approval time if the property to ensure functionality techniques A Citizen’s Guide to Stormwater Retrieved January 15, 2009.

development/redevelopment incorporates one Management in Maryland. Available

or more of the following: Identify LEED point potential outside

online. Retrieved January 15, 2009.

of structures (stormwater volume

LID and green infrastructure reduction, water quality, urban heat US Green Building Council. LEED for

Shared driveway techniques island) and provide incentives for Neighborhood Development. Available

Shared parking including LEED points in the site online. Retrieved January 15, 2009.

Transit-oriented developments or design

mixed-use Grant additional open space credit

Narrow or shared driveways for off-site LID/green Infrastructure

that is improved/designed for public

Cluster development recreational purposes and social

Phased construction value

Plans for reduced soil disturbance Provide incentives, such as

and/or compaction increased Floor Area Ratios, for

Retaining or amending topsoil green roofs that reflect

environmental, economic and social

Surface swales and ditches instead benefits

of storm sewer

Create formal program offering

Retaining existing trees on site incentives to property owners who

Street bioswale

Rear-loaded garages use pervious pavement elements

Reduce stormwater management

facility requirements for

developments employing

comprehensive rainwater

harvesting*

Permeable pavers and bioswale

Sustainable Community Development Code Beta version 1.2 12

ACHIEVEMENT LEVELS

Bronze (Good) Silver (Better) Gold (Best) References/Commentary Code Examples/Citations

Enact

Standards

Require runoff reduction techniques Integrate LID and “No Adverse Require that new Urban Drainage Flood Control District. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

for new development and Impact” recommendations from development mimics pre- Urban Drainage Criteria Manual Site Design checklist. Available

redevelopment Association of State Floodplain development hydrology Volume 3 – Four Step Process: BMP online.

Require and enforce riparian buffer Managers into the local development Require and enforce riparian Planning for New Development and Center for Watershed

strips that adequately protect riparian code buffer strips of at least 100 Redevelopment, section 1.2: Available Protection. Code and Ordinance

functions and values Require and enforce riparian buffer feet that adequately protect online. Worksheet. . Available online.

Integrate LEED requirements with strips of at least 50 feet that riparian functions and values Association of State Floodplain National Association of

Porous landscape detention

stormwater benefits in the building adequately protect riparian functions Require no net runoff volume Managers. Resources available Homebuilders. Model Green

and land development code and values increase when variances for online. Home Building Guidelines.

Integrate National Association of Require redevelopment projects to extra parking are granted Stormwater Center. Better Site Design http://www.nahbgreen.org/conte

Home Builders’ Model Green Home increase porosity and permeability When technically feasible, Fact Sheet: Narrower Residential nt/pdf/nahb_guidelines.pdf

Building Guidelines in land Require developers to conduct a require porous/permeable Streets. National Association of

development code natural resource inventory prior to pavement options for right-of- www.stormwatercenter.net/Assorted% Homebuilders .Tree

site design way and emergency access: 20Fact%20Sheets/Tool4_Site_Design/ Preservation Ordinances .

Evaluate actual parking needs for narrow_streets.htm

residential and commercial Require that high quality topsoil be fire lanes, shoulders, alleys. Available online.

development and revise parking saved and replaced onsite or soil Establish maximum parking U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Stormwater Center. Model

Private road with standards accordingly must be augmented with organic limitations instead of, or in Residential LID Tools. Available Ordinances for Aquatic

detention under pavers materials addition to, minimum parking online. Resource Protection. Available

Prohibit roof downspouts from

discharging to impervious surfaces Prohibit excessive soil compaction requirements. Nonpoint Education. Addressing online.

such as driveways by requiring laying mulch, chipped Establish a system that Imperviousness in Plans, Site Design Urban Design Tools: Low

wood, or plywood sheets before allows/requires payment-in- and Land Use Regulations. Available Impact Development http://lid-

Require porous/pervious materials be online.

used in areas of parking lots that will construction equipment enters site lieu fees for off-site LID/green stormwater.net/

be used for snow storage Require parking lot landscaping that Infrastructure . Center for Watershed Protection Site Southeast Metro Stormwater

promotes infiltration, such as porous Require developers to meet Planning Model Development Authority: Criteria Manuals,

Enact tree ordinances that protect Principles

landscape detention, swales, and at least 50% of their Templates, and Sample

existing trees and require new trees http://www.cwp.org/22_principles.htm

filter strips stormwater requirements with Drawings. Available online.

to be planted in such a way as to

develop/maintain healthy tree cover Require pervious parking for the LID/green infrastructure Guidelines for Developing and Lacey, Washington. Zero

spaces constructed beyond the practices. Evaluating Tree Ordinances. Available Impact Development Ordinance.

Require operations and maintenance online.

plan for LID and other stormwater average needs http://www.ci.lacey.wa.us/lmc/lm

Street bioretention

structures for new and Require developers to meet at least c_main_page.html

redevelopment 25% of their stormwater Natural Resources Defense

Require developers to meet a requirements with LID/green Council. Stormwater Strategies:

specified percentage of their infrastructure practices. Community Responses to

stormwater requirements with Adopt regulations to protect steep Runoff Pollution: Chapter 12:

LID/green infrastructure practices slopes, hillsides, and other sensitive Zero Impact Development

natural lands Ordinance

Require any public trees removed or

http://www.nrdc.org/water/polluti

damaged during construction be Adopt an impact fee that is used to

on/storm/chap12.asp

replaced on- or off-site with an purchase open space that assists in

equivalent amount of tree caliper stormwater management Douglas County. Grading,

(e.g., remove a 24-diameter Erosion and Sediment control

tree/replace with 6 four-inch diameter Manual. Available online.

trees)

Sustainable Community Development Code Beta version 1.2 13

ACHIEVEMENT LEVELS

Bronze (Good) Silver (Better) Gold (Best) References/Commentary Code Examples/Citations

Differentiate between greenfield, Require long-term maintenance

brownfield and infill development in agreements that allow for public

local codes, ordinances, and policies inspections of the management

Allow two-track driveways by practices and also account for

technical street/subdivision transfer of responsibility in leases

specifications and/or deed transfers

Require all road/street projects to Conduct regular inspections,

allocate a minimum amount of the prioritizing properties that pose the

total project cost to LID/green highest risk to water quality

infrastructure elements Develop a plan approval and post-

Adopt requirement that some construction verification process to

percentage of parking lots, alleys, or ensure that stormwater standards

roads in a development use pervious are being met, including enforceable

Permeable pavers with high albedo materials procedures for bringing

noncompliant projects into

Require large developments to adopt compliance

transportation demand management

techniques to lower vehicle use and

parking demand

STRATEGIC SUCCESS FACTORS

Supportive planning policy and programs support and compliment regulations and are listed here as strategic success factors.

Local government creates formal program offering incentives (e.g., cost sharing, reduction in street widths/parking requirements, assistance with maintenance) to property owners who utilize pervious pavement element

Support or partner with land trusts to acquire critical natural areas

Adopts funding mechanisms for remediation and redevelopment of brownfield sites.

Establish a dedicated source of funding for open space acquisition and management

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

End notes

1. Elvidge,C.D.,C. Milesi,J.B.Dietz,B. Tuttle,P.C.Sutton, R. Nemani and J.E. Vogelmann (2004), U.S. Constructed Area Approaches the Size of Ohio, EOS,Vol. 85, No. 24, 15 June 2004.

2. Full Spectrum Detention 2005-01-01 Concept Paper, James Wulliman and Ben Urbonas, 2005. http://udfcd.org/downloads/pdf/tech_papers/Full%20Spectrum%20Detention%202005-01-01%20Concept%20Paper.pdf

3. Urban Watershed Research Institute – Low Impact Development training class October, 2006, Ben Urbonas.

4. Association of State Floodplain Managers - National Flood Programs and Policies in Review, 2007 http://www.floods.org/Publications/NFPPR_2007.asp

5. http://www.wetlands-initiative.org/FloodDamageSummary.html

6. Protecting Our Waters: Subdivision Design, http://clean-water.uwex.edu/plan/subdivision.htm

7. EPA 841-F-03-003. Protecting Water Quality from Urban Runoff.

8. Better Site Design Fact Sheet: Narrower Residential Streets

9. Site Planning for Urban Stream Protection: Chapter 4 - Stream Protection Clusters

10. http://www.oeconline.org/rivers/stormwater/impacts

11. Pg 11: http://www.dep.state.pa.us/dep/subject/advcoun/Stormwater/Manual_DraftJan05/Section08-jan-rev.pdf

12. City Of Boulder, Colorado Municipal Tree Resource Analysis

*Rainwater harvesting techniques that impede the flow of gravity and capture water for use at some later time (including pumping or bucket dipping) are currently prohibited in Colorado without a water right. Low impact development techniques that mimic predevelopment hydrology though infiltration, absorption

(landscaping) or by not producing runoff in the first place (porous and permeable pavements), are legal.

Sustainable Community Development Code Beta version 1.2 14

2. Preserve critical environmental areas such as wetlands, forests, and riparian corridors from encroachment

Wildlife Habitat and Biodiversity Protection by development

Revised 5-26-09 3. Conserve water thus reducing pressure to divert and dam rivers and streams, the most significant habitat in

many ecosystems

4. Remove exotic species, particularly plants, from development sites and prohibit their introduction

5. Reduce greenhouse gas emissions and thus reduce climate change and pressure on existing habitats and

species (See chapter on climate change for tools.)

INTRODUCTION

In the early 20th Century, the biggest threats to wildlife were over-hunting and over-fishing.

Mankind is still the biggest threat to wildlife, but the primary reason today is destruction of critical

habitat by development. One-third of all species in the United States are at serious risk. In fast

growing states like Florida, Texas, and California the threats to native ecosystems were rated as

extreme in one recent study. These problems have been exacerbated by global warming and

climate change that are putting added stress on wildlife.

Fortunately, and often because of the value of wildlife to their local economies, local governments The increased distance between habitat patches makes it less likely wildlife will be able to travel between

across the United States are taking action to preserve wildlife habitat and biodiversity. patches.

Source: USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service - Watershed Science Institute

IMPLICATIONS OF NOT ADDRESSING THE ISSUE

Environmental guru Lester Brown, in his sobering book Plan B, warns that if action is not taken

quickly and decisively, mankind will witness the sixth major species extinction event in history.

According to Brown, the first five were caused by natural disasters and climate change. This one

will be laid at the feet of humans, because it will result mainly from habitat destruction—from

forests to prairies, wildlife habitats are under threat as never before.

The result of that loss will be immeasurable not only in economic terms, but also in terms of man’s

quality of life and the character of our communities. As noted biologist Edmund O. Wilson has

observed, “Surely the rest of life matters.”

GOALS FOR WILDLIFE HABITAT AND BIODIVERSITY PROTECTION The fragmented landscape on the left in this illustration has 60% more edge than the unfragmented landscape on

the right. When habitat patches are fragmented, the linear feet of edge increase favoring species that prefer

Land use and zoning regulations can play an important role in helping to protect wildlife habitat in a number of ways. edge habitat and often increasing predation and parasitism that need core habitat species

These are incorporated into the primary goals for wildlife habitat and biodiversity protection. Source: USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service - Watershed Science Institute

Removing regulatory obstacles to wildlife habitat and biodiversity protection

Establish incentives to protect wildlife habitat

Establish standards that accomplish the following:

1. Protect large contiguous blocks of wildlife habitat and open space and prevent fragmentation by

development.

Sustainable Community Development Code Beta version 1.2 15

Sustainable Community Development Code

WILDLIFE HABITAT AND BIODIVERSITY PROTECTION

KEY STATISTICS:

Note to reader: citations forthcoming

One-third of the best-known species of plants and animals are at risk and more than 200 species of U.S. fauna and flora are already extinct.

27 ecosystem types have declined 98% or more since the European settlement of this country. Prairies, sagebrush steppes, and oak savannas are just a few that have been almost entirely wiped out.

Significant declines have been document for almost 30% of North American bird species—most due to factors such as loss of wetlands and native grasslands as well as poor land use decisions.

In 2001, U.S. residents spent about $108 billion on wildlife watching.

A study of 17 conservation areas acquired under Florida’s Conservation and Recreation Lands, Preservation 2000, and Florida Forever program estimated their economic impact at $128 million in retail sales, 1,200 jobs, $21.7 million in

wages, and $7.2 million in state sales tax.

Almost 50% of mainland U.S. residents participated in nature-based activities on their last vacation.

A study in California in the 1990s calculated that wetlands provided up to $22.9 billion in value annually including water supply, water quality, recreation, and fishing-related jobs.

According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, in 2006 nearly 60 million anglers generated over $45 billion in retail sales and created employment for 1 million people. Fishing is one of the most popular outdoor activities of lower-income citizens.

A national bipartisan poll conducted in 2004 revealed that 65% of American voters would support modest tax increases to pay for programs to protect wildlife habitat, water quality, and neighborhood parks. Latino voters weighed in with 77% support. An earlier

similar survey by the National Assn. of Realtors found that more than 80% of voters support preserving farmland, natural areas, stream corridors and historic areas under pressure for development.

WILDLIFE HABITAT AND BIODIVERSITY PROTECTION

ACHIEVEMENT LEVELS

Bronze (Good) Silver (Better) Gold (Best) References/Commentary Code Examples/Citations

Remove Allow cluster/conservation subdivisions in Reduce sprawl and encourage infill Restrict septic systems in rural See Randall Arendt’s For general agricultural

Obstacles urban/rural transition areas development by adopting tailored standards areas with significant wildlife Conservation Design For zoning references see the

Identify preferential development sites; for parking, open space, and storm water habitat Subdivisions (1996) and Municipal Research and

rezone to allow development by-right management (see Climate Change chapter) Adopt true rural zoning (1 unit/80 Rural By Design (1994). Services Center of

Repeal small-lot (< 1unit/20 acres) residential acres+) in sensitive wildlife habitat Chicago: American Planning Washington. online.

To reduce sprawl and protect open space,

or agricultural zone districts in sensitive rural areas Association. Retrieved May 26, 2009.

allow mixed-use development districts that

Rocky Mountain Arsenal habitat areas Illustrative conservation University of Wisconsin

allow denser development by-right Ban planned unit developments in

National Wildlife Refuge designs by Foth and Van Extension provides the

To avoid fragmentation of wildlife habitat, To facilitate clustering on small lots in a rural jurisdictions in vicinity of

conservation subdivision, allow community sensitive natural areas Dyke. online. Retrieved May basic elements of a

remove subdivision requirements for

septic systems 21, 2009. conservation subdivision

individual lot access drives and allow shared Require developers to provide

Wells, Barbara (2002). ordinance. Available online

driveways adequate funding to undertake

Smart Growth At The here and . Retrieved May

wildlife habitat impact analysis for

Frontiier. Northeast-Midwest 21, 2009.

large projects

Institute. online. Retrieved Summary ordinance

May 21, 2009. requirements for

Daniels, Tom (1999). What to conservation subdivisions

Do About Rural Sprawl, in selected Wisconsin

(1999). Paper Presented at communities. online.

The American Planning Retrieved May 21, 2009.

Association Conference, For a description of PUDs

Cluster subdivision protecting Seattle, WA with a pro/con scorecard,

woodland. Source: Foth & Van April 28, 1999. online. see the Center for Land

Dyke. Retrieved May 21, 2009. Use Education, Planned

Duerksen, Chris and Snyder, Unit Development (2005).

Sustainable Community Development Code Beta version 1.2 16

Sustainable Community Development Code

WILDLIFE HABITAT AND BIODIVERSITY PROTECTION

Cara (2005). Nature-Friendly Available online. Retrieved

Communities. Washington: May 21, 2009.

Island Press. See case

studies of Baltimore County,

MD, and Dane County

(Madison), WI, for effective

growth management on the

urban/exurban interface.

Barnes and Adams, A Guide

to Urban Habitat

Conservation Planning, offers

a good summary of issues to

consider for urban wildlife

habitat plans and ordinances.

online. Retrieved May 21,

2009.

Create Offer density bonuses for provision of large Adopt a development rights transfer program Adopt a purchase of development Pruetz, Rick (2003). Beyond Farmland

Incentives blocks of contiguous open space to provide incentive for open space rights (PDR) program and support Takings and Givings. Arje development rights in

Grant extra credit against subdivision and preservation with a significant or dedicated Press. Considered the Suffolk County, New

PUD open space requirements for active Identify and map critical habitat sites where funding source (e.g., sales tax leading publication on YorkSuffolk County, NY.

wildlife management development is discouraged earmark) transferable development A description of one of

rights strategies and the nation’s first PDR

Grant additional open space credit for

After being on the verge of ordinances. Description programs. online.

removal of exotic vegetation

extinction in 1967, the available online. Retrieved Retrieved May 27, 2009.

American bald eagle has May 21, 2009.

officially been taken off the Skoloda, Jennifer (2002),

endangered species list today. Wildlife Habitat In A

Comprehensive Plan. Center

for Land Use Education.

Summary of how to integrate

wildlife habitat considerations

in a local comprehensive

plan. online. Retrieved May

21, 2009.

For excellent overviews of

PDR programs, see Purchase

of Development Rights:

Conserving Western Lands,

Bird house in an area

Preserving Western

protected by a conservation

easement. Cherokee Ranch,

Livelihoods (2002). Western

Douglas County, CO Governors’ Assn. online.

Retrieved May 21, 2009.

Sustainable Community Development Code Beta version 1.2 17

Sustainable Community Development Code

WILDLIFE HABITAT AND BIODIVERSITY PROTECTION

Enact Require a significant minimum percent open Limit the size of planned unit developments in Require new development to Conservation Thresholds for Mark Bobrowski and

Standards space set aside requirement in all rural zone districts or prohibit entirely offset any loss of critical habitat by Land-Use Planners (2003). Andrew Teizt, Model Land

subdivisions (e.g., 75% in rural areas). Adopt true large-lot agricultural zoning (e.g., 1 requiring purchasing conservation Environmental Law Institute. Use Ordinance to Protect

Require wildlife habitat to be protected as part unit/80 acres rights or lands elsewhere A review and synthesis of the Natural Resources,

of any open space set aside Create urban services boundary to basic conservation standards online. Retrieved May 26,

Adopt water-conserving landscaping

Adopt tree and vegetation protection restrict development outside of rely on in reviewing 2009.

standards

ordinances designated growth areas development proposals. Florida Wildlife-Friendly

Require the use of conservation subdivisions online. Retrieved May 26,

Adopt wildlife-friendly fencing standards Adapt comprehensive wildlife Toolbox is an on-line

in urban/rural transition areas with large 2009.

protection regulations (See resource containing sample

Require use of native plants in landscaping minimum open space requirement

references to Summit County, CO, Nolon John (2003). Open plans and ordinances

plans Adopt development setbacks (e.g., 100 feet)

and Teton County, WY) Ground: Effective Local relating to conservation of

Adopt fiscal impact analysis requirements for from all sensitive natural areas (wetlands, Strategies for Protecting wildlife habitat. online.

large developments riparian areas, critical wildlife areas) Natural Resources. Retrieved May 26, 2009.

Require removal of exotic vegetation on Washington: Island Press. Summit County, Colorado,

Pronghorn Antelope Migration development sites Provides a comprehensive Wildlife Habitat Overlay

Preservation. Source: Wildlife look at local land preservation

Adopt open space impact fees District. online. Retrieved

Conservation Society strategies and tools.

Ban domestic pets in developments near May 26, 2009.

sensitive wildlife habitat Information online.

Retrieved May 26, 2009. Salt Lake City Riparian

Habitat Protection

Development and Dollars: An Ordinance (urban habitat

Introduction To Fiscal Impact protection). online.

Analysis in Land Use Retrieved May 26, 2009.

Planning. Natural Resources

Defense Council. online. Tucson, AZ, water

Retrieved May 26, 2009. conservation ordinances.

online. Retrieved May 26,

Duerksen, et al, Habitat 2009.

Protection Planning: Where

The Wild Things Are. PAS Natural, Scenic,

Polar Bear. Recently listed as

Report 470/471. American Agricultural and Tourism

a threatened species due to

global warming. Planning Assn. (1997). Resources Protection.

online. Retrieved May 26, Teton County, (Wyoming).

2009. Land Development

Regulations, (Article III). .

Duerksen, Chris and Snyder, online. Retrieved May 27,

Cara (2005). Nature-Friendly 2009.

Communities. Washington:

Island Press.) See case Progressive habitat

studies Teton County, WY, protection ordinances

and Sanibel, FL , for addressing environmental

progressive habitat protection performance standards,

ordinances interior wetlands

conservation district, beach

For a discussion of tree and sand dune system.

conservation ordinances, see Sanibel (Florida) Code

Model Tree Protection (Articles XIII, IX, VII).

Ordinance. Scenic America. online. Retrieved May 27,

online. Retrieved May 26, 2009.

2009.

Sustainable Community Development Code Beta version 1.2 18

Sustainable Community Development Code

WILDLIFE HABITAT AND BIODIVERSITY PROTECTION

Strategies for Managing the

Effects of Climate Change on

Wildlife and Ecosystems. The

Heinz Center. online.

Retrieved May 26, 2009.

McElfish, James (2004).

Nature-Friendly Ordinances

Environmental Law Institute.

STRATEGIC SUCCESS FACTORS

Regulatory tools must be grounded in solid comprehensive policy planning and accompanied by competent administration and supportive programs.

PLANNING POLICY

Identify high-priority resource protection areas in local plans and undertake specific area plans to protect.

Coordinate local government capital improvement plans to avoid extending infrastructure into or near critical wildlife habitat

PROGRAMS & ADMINISTRATION

Counties provide financial assistance for their towns to plan/revitalize local business districts—helps reduce rural commercial sprawl.

Coordinate parks and open space planning with wildlife habitat protection. Identify key habitats to acquire and protect

Add resource biologist/planner to staff to provide thorough review of wildlife impacts of projects.

Provide funds for local land trusts to assist in open space protection

Sustainable Community Development Code Beta version 1.2 19

Water Conservation

Revised 1-29-09

INTRODUCTION

Worsening drought, population growth, and record wildfire seasons in recent years have called sharp attention to the

need to make more efficient use of our water supply. While states and communities in the arid Southwest have

understandably led the charge in improving municipal water efficiency through regulations, even cities on the water-rich

Great Lakes like Chicago have found themselves exceeding their water allowances and developing efficiency

strategies. 1 For municipal water providers, water availability is a three-part equation of water supply (surface and

ground plus storage), water treatment capacity, and water distribution capacity. Each part of the equation poses costs

and challenges to communities in the form of acquiring adequate water rights and investing and maintaining the

treatment and distribution infrastructure. In the next 20 years, the US will add approximately 53 million more people and

will have to rise to the challenge of meeting their drinking, bathing, irrigation, and commercial processing needs with a

finite supply of fresh water. have to improve their performance sooner or later. However, the implications for waiting are costly. Communities that

have embraced water conservation measures have enjoyed significant reductions in overall water consumption for both

This section reviews a range of tools from managing peaks in demand to recycling gray water for irrigation. Models are residential and non-residential development.

drawn from a variety of communities across the US including Arizona, California, Minnesota, Florida, and

Massachusetts as well as organizations such as US Green Building Council’s Leadership in Energy and Environmental Southwestern communities, whose long relationship with water conservation measures has allowed for analysis, have

Design (LEED) program and the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) Model Green Home Building enjoyed marked improvements since implementing conservation ordinances. From 1994-2005 Albuquerque, NM,

Guidelines. The regulations are divided into the following ordinance categories: decreased system-wide per capita use from 250 gallons per day to 173g/d while Tucson, AZ, reduced consumption

from 169 g/d to 156 g/d. Improvements can also be more immediate. In only three years, the Las Vegas Valley brought

Efficient Landscaping their per capita consumption down from 283 g/d to 256 g/d. Reducing demand on the water supply system helps to

Water Use/Waste extend the life of existing infrastructure, eliminate or prolong the need for system capacity upgrades for treatment,

Water Harvesting distribution, and storage, and enhances a community’s ability to deal with a drought.

Greywater Recycling

GOALS FOR WATER CONSERVATION

It is worth noting that the vast majority of communities with water conservation ordinances in place couple those The primary goals of the tools discussed in this section are to:

regulatory tools with a variety of educational materials and financial incentives to promote additional efficiency. Reduce community per capita water use while retaining attractive landscapes

Education campaigns target everything from everyday options for reducing waste to introducing new technologies or

Enable communities to meet future needs of their growing populations

practices such as rain gardens or rainwater harvesting. Incentives are often in the form of rebates that facilitate

efficiency updates to existing buildings such as rebates for installing water efficient appliances, toilets, faucet aerators, Protect ground and surface water supplies from unsustainable depletion

and shower heads as well as in the landscape through such means as turf removal credits and free or discounted rain Eliminate unnecessary waste in water use practices

sensors for irrigation systems. These programs help promote the adoption of new technologies and practices and help Reduce wastewater treatment volume and associated municipal expenditures; and

improve efficiency of existing development not impacted by many of the regulatory tools. Any community interested in Promote the increased use of harvested and recycled water for irrigation needs

improving water efficiency should consider education and incentive tools in conjunction with regulations as part of their

overall strategy.

Special Note :Not all provisions suggested are legal in all states. Colorado law restricts re-use generally for tributary

IMPLICATIONS OF NOT ADDRESSING THE ISSUE waters-meaning no harvesting barrels

Failing to establish water conservation provisions at the local level can have significant impacts on the future growth,

economy, and food supply of a community. Water is essential to life and as such one can argue that communities will

1 City of Chicago, Chicago’s Water Agenda, 2003, Mayor Richard M. Daley

Sustainable Community Development Code Beta version 1.2 20

DRAFT Sustainable Community Development Code Framework

WATER CONSERVATION

KEY STATISTICS:

The population of the US is anticipated to increase to 250 million people by 2040

Ninety percent of all drinking water in the US is pumped from groundwater supplies and most communities have witnessed falling water tables. Water use is exceeding the recharge rate

Global warming forecasts foresee steadily increasing temperatures worldwide, with more extreme storms, increased drought in some locations and increased flooding in others

Landscape irrigation accounts for approximately 51 percent of all domestic water consumption in the U.S.

There is a high level of variability in per capita water consumption between municipalities in comparable climatic zones (e.g., in 2005 the average single-family residential water consumption in Tucson, AZ, was 114 gallons per capita per day compared to

174 in Las Vegas, NV) indicating the potential for more efficient consumption patterns

WATER USE AND WASTE

Achievement Levels

Bronze (Good) Silver (Better) Gold (Best) References/Commentary Code Examples/Citations

Remove Identify limiting ordinances (e.g., Allow attractive hardscaping Override private covenants and Wisconsin Department of Las Vegas Valley communities

Obstacles CC & Rs) that require the use of alternatives to landscaping restrictions that require turf grass Natural Resources, Rain served by Southern Nevada Water

turf in lawns and common areas requirements (e.g., ornamental or limit water-conserving Gardens: A how-to Authority including Boulder City,

and craft exceptions to the limiting gravel, mulch) landscaping manual for homeowners Henderson, North Las Vegas, Clark

ordinances (2003) County, Las Vegas (multiple

Permit rain gardens, drainage ordinances)

swales, and similar facilities by Tucson, AZ (Water Waste and

right Tampering Ordinance – Ordinance

Create More information on rain 6096, Plumbing Codes – Ordinance

Grant extra landscaping credit Accelerate permitting for Give extra landscaping credit for

Incentives for rain gardens protection of native plants on site gardens and sample 7178, Emergency Water

developments meeting LEED-ND

water conservation standards garden plans available Conservation – Ordinance 8461),

Give bonus points in design available online at

review systems for water online at

http://www.ci.tucson.az.us/water/ordi

conservation and water http://www.raingardens.or

g/Index.php nances.htm

harvesting

U.S. Green Building Council, LEED

Enact Include optional low-water Require all new commercial and Require use of on-site or Albuquerque, NM enjoyed for Neighborhood Rating System

Standards landscaping or plant list as multi-family development to use municipal recycled /harvested a 35% decrease in single- (See reduced water use credits,

part of landscaping code Xeriscape (drought tolerant) water for non-potable uses family residential daily per p.101.), available online at

principles and low-water plants capita water consumption ://www.usgbc.org/ShowFile.aspx?Do

from established plant list in after adopting water- cumentID=2845

landscaping efficient landscaping

provisions

Sustainable Community Development Code Beta version 1.2 21

DRAFT Sustainable Community Development Code Framework

WATER CONSERVATION

WATER USE

Achievement Levels

Bronze (Good) Silver (Better) Gold (Best) References/Commentary Code Examples/Citations

Remove Update building code to be in full Las Vegas Valley communities

Obstacles compliance with the US Energy served by Southern Nevada Water

Policy Act of 1992 (EPAct) Authority including Boulder City,

Create Western Resource Henderson, North Las Vegas, Clark

Allow increased density in Large Customer Mandatory

Incentives exchange for reduced water use in Water Conservation Plan – Advocates, Water in the County, Las Vegas (multiple

ordinances)

multi-family developments require large water users (e.g., Urban Southwest (2006)

those consuming more than Santa Monica, CA (No Water Waste

50,000 gpd) to submit a long- Ordinance), available online at

range water conservation plan http://www.smgov.net/EPD/residents/

that addressed both indoor Water/waste_ordinance.htm

and outdoor water use. San Francisco, CA (Residential

Clearly define enforcement Water Conservation Ordinance) ,

methods and associated available online at

penalties in the ordinance http://www.sfgov.org/site/uploadedfile

s/dbi/Key_Information/19_ResidEner

Enact gyConsBk1107v5.pdf

Prohibit landscape watering Regulate days of the week Regulate water-wasting

Standards between 11 am and 7 pm during watering is allowed (e.g., outdoor activities such as Austin, TX, Water Use Management

hot and dry months (as defined by alternate days by even v. odd hosing down pavement, Ordinance, available online at

local temperature and precipitation street numbers) buildings, or equipment unless ://www.ci.austin.tx.us/watercon/water

patterns) runoff is returned directly to a ordinance.htm

Restrict watering on steep

slopes stormwater drain Flagstaff, AZ

Regulate wasteful residential ://www.flagstaff.az.gov/index.asp?nid

Require installation of water =104

meters on all new construction irrigation practices such as

or rehabilitation misdirected spray heads, Shrewsbury, MA

runoff into driveway or http://www.shrewsbury-

adjacent lots, and broken or ma.gov/sewerwater/publicnotice.asp#

leaking sprinklers conservation

Require all new and renovated

car washes to install water

recycling systems

Sustainable Community Development Code Beta version 1.2 22

DRAFT Sustainable Community Development Code Framework

WATER CONSERVATION

WATER CONSERVATION: REDUCE DEMAND ON WATER TREATMENT AND DELIVERY SYSTEMS*

Rainwater Harvesting and Achievement Levels

Greywater Recycling Bronze (Good) Silver (Better) Gold (Best) References/Commentary Code Examples/Citations

Remove Identify limiting regulations and Allow above- and below- Allow water storage tanks as a Tucson Water, Water Harvesting (FL) Palm Beach County

Obstacles private covenants (e.g., ground water storage tanks by-right accessory use except in Guidance Manual (2005) Reclaimed Water Ordinance

homeowner association CC & Rs) as a conditional use except special districts (e.g., historic Texas Water Development Board, The (Ord. No. 97-12, § 1, 5-20-97)

and craft exceptions that include in special districts (e.g., districts) or locations where Texas Manual on Rainwater available online at

rainwater harvesting tanks historic districts) or locations water rights law prohibits on-site Harvesting (2005) http://www.municode.com/resou

Where state water law allows, where water law prohibits retention of rainwater rces/gateway.asp?sid=9&pid=1

Lighthouse, BC Green Building Code

repeal any ban on the ability of on-site retention of rainwater 0323

Background Research: Greywater

development to have on-site Recycling (2007)

rainwater harvesting systems

://www.housing.gov.bc.ca/building/gre

Work with legislators to update en/Lighthouse%20Research%20on%2

state law where current regulations 0Greywater%20Recycling%20Oct%20

completely or effectively prohibit 22%2007%20_2_.pdf

greywater recycling. Arizona is

Arizona State law on greywater

commonly regarded as the best

recycling with further analysis and

example of statewide legislation for

state-by-state comparative discussion

greywater recycling

available online at

://www.oasisdesign.net/greywater/law/

index.htm#arizona

Create Reduce/eliminate permit fees for Offer credits to residential and

Incentives installation of water storage tanks commercial developments that

Revise plumbing and building code install water harvesting systems

requirements to allow for greywater Eliminate permit requirement for

recycling systems greywater recycling systems for

small residential systems

Enact Create specific screening Require the installation of Require specified percentage of Florida currently has a water

Standards requirements to apply to this use recycled water distribution irrigation water in a development recycling capacity of 1.1 billion

appropriate to the use context infrastructure in all new to come from grey water or gallons/day, over half of its total

Local jurisdictions can further refine development so recycled harvested rainwater wastewater treatment capacity

the list of system size and design water use is an option for Require greywater recycling Florida Department of

requirements for different capacity irrigation systems. Environmental Protection, Florida

systems and associated standards Require development design Water Conservation Initiative

above those established in to include water harvesting (2002)

applicable state law for landscape irrigation

Sustainable Community Development Code Beta version 1.2 23

Wildfire Hazard in the Wildland-Urban Interface

Revised 1-28-09

INTRODUCTION

Wildfire is a natural hazard that occurs throughout a variety of regions in the United States. Wildfire severity and

frequency may depend on a host of factors, not limited to a region’s topography, fire history, forest management

practices, weather patterns and fuel type. Many ecosystems—including southwestern California chaparral, Midwest

tallgrass prairie, and various pine stands of the Southwest, Rocky Mountains and Southeast—depend on fire for natural

biological functions. 1 In addition to ecosystem benefits, however, wildfire acts as a risk to communities by jeopardizing

personal safety and property, threatening watersheds, crippling infrastructure, prompting erosion and landslides,

temporarily displacing residents, impacting recreation and tourism opportunities, and leading to other destructive Other challenges in reducing wildfire risk include varying perceptions of risk. A good deal of research indicates that

outcomes. These economic, ecologic, and social risks can be exacerbated through land use and development homeowners often underestimate their individual risk to wildfire. 4 This can lead to resistance to regulations on private

decisions that allow increased growth in areas prone to wildfire—the area known as the wildland-urban interface, or property or decisions to live in areas that are prone to recurring wildfires. Additionally, a lack of financial resources for

WUI. performing mitigation such as tree thinning or roof replacements, may inhibit well-intentioned homeowners.

It is common for many communities to perform wildfire mitigation in the WUI. These techniques, such as thinning trees

on private and public lands, maintaining forest health through appropriate management, and requiring non-flammable GOALS FOR REDUCING WILDFIRE RISK IN THE WUI