Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Research

Uploaded by

JangOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Research

Uploaded by

JangCopyright:

Available Formats

19

Making Sense of Being and Becoming

Filipinos: An Indigenous Psychology

Perspective

JAY A. YACAT

University of the Philippines, Diliman

This qualitative study explored how 36 undergraduate students from

the University of the Philippines who were born, raised and currently

residing in the Philippines make sense of their "pagka-Pilipino" (being

Filipinos). Using the method of ginabayang talakayan (indigenous

facilitated discussions), it was found that notions of "being Filipino"

were shaped by any of three factors: a sense of shared origins

(pinagmulan); growing up in a similar cultural milieu (kinalakhan) and

a shared consciousness (kamalayan). This may suggest uniformity in

the participants' defmitions of "who the Filipino is" but analysis reveals

that different people and groups tend to place different emphases on

the three factors in their own attempts to come to terms with their

identities as Filipinos. Hence, "Filipino" and "being Filipino" may evoke

different meanings among different people.

National identity may be considered as one of the most

complex, even most highly contested, concepts in this modern

era. It may also have brought about the most dramatic effects,

both positive and negative, in world history (Salazar, 1998).

National identity has been the rallying cry of the colonized as

they fought for their freedom and independence from colonizers.

But at the same time, it also served as fuel for the oppression

and discrimination of individuals and groups considered as "not

one of us".

Despite these powerful yet opposite effects, interest on national

identity within psychology remains to be rather limited. The

individualist focus in mainstream psychology may account for

PHILIPPINE JOURNAL OF PSYCHOLOGY (2005), Vol 38 No 2, pp. 19-37.

20

this lack of interest. National identity and its relative, nationalism,

may be deemed as too "macro" a construct for a psychological

lens. Another reason may be that the concept may be too difficult

to manage or operationalize since the affiliate concept of nation

is also fraught with much semantic confusion (Jackson & Penrose,

1993). I found that if national identity is discussed, it is framed

rather negatively, e.g., as a source of intergroup tensions (Cassidy

& Trew, 1998) or in the reproduction and maintenance of

stereotypes.

However, the increasing popularity of social categorization

approaches may have provided some initial spark to this fledgling

domain: Credit could be given to Tajfel (1969, 1970) who

acknowledged the importance of membership to broader social

groups such as the nation to our social identity. This recognition

provided the preliminary basis for the development of his social

identity theory (Salazar, 1998).

In contrast, national identity has been a long standing concern

in the Philippines. However, Conaco (1996) observed that the

popular approach is to examine the concept in its socio-political-

historical context. Examples of this approach would be

Constantino's (1974) treatise on the mis-education of the Filipino

and even Enriquez's (1977) critique on supposedly Filipino national

values. In a series of surveys, Doronila (1982, 1989 and 1992)

provided the earliest empirical work on Filipino national

identification.

Within Philippine psychology, however, very few empirical

studies have been conducted. Cipres-Ortega (1984) explored the

development of social-psychological concepts, including national

identity, among children. Using a social cognitive approach, Conaco

(1996) examined the location of national identity within the matrix

of social identities identified as relevant by Filipino college students.

In general, the dominant discourse on national identity tends

to focus only on the political aspects. Hence, there is a tendency

to use national identity and citizenship interchangeably (Azurin,

1995). In this sense, national identity becomesa purely political

identity and refers only to identification with the state. However,

21

an emerging view treats national identity also as a cultural identity

(Anttila, 1997).

I feel that the role of culture in identity should never be

underestimated nor neglected. I define culture as a system that

creates meaning. A model called the circuit of culture demonstrates

a process whereby culture gathers meaning at five different

'moments' - representation, identity, production, consumption,

and regulation (du Gay, et al., 1997). Each of these 'moments' is

interlinked with the other 'moments' in an on-going process of

cultural encoding and dissemination. According to this formulation,

identities are created, used and regulated within a culture that

provides a set of meanings through a symbolic system of

representation that feeds on identity positions.

Following this formulation, it is interesting to see how

representations influence identity positions and vice versa. In

particular, it would be fascinating to examine how representations

of what it means to be a Filipino influence and are influenced by

our identity positions as Filipino.

Figure 1. The circuit of culture

22

This sensitivity to culture as a primary context for meaning

(and the subsequent creation and representation of identities) is

one of the arenas of the indigenous psychology perspective.

Enriquez (1976) decried the seemingly uncritical acceptance of

Western theories, models, techniques and methods that dominated

Philippine psychology in the 1970s. This lack of sensitivity to

Filipino cultural conditions, in his view, led to a psychology that

is alienating and alienated from the very people it was designed

to serve. He envisioned to formalize a psychology that would be

sensitive to Filipino realities and context, a psychology he termed

as sikolohiyang Pilipino (Filipino psychology), but without neglecting

knowledge derived in Western psychology that was found to be

applicable to the Philippine setting (Enriquez, 1994). Thus, the

indigenization of psychology in the Philippines was started.

Sinha (1997) identified four threads that define indigenous

psychological perspectives: a) arise from within the culture;

b) reflect local behaviors; c) interpret data from a local frame of

reference; .and d) yield results that are locally relevant. In essence,

indigenous psychology aims to produce knowledge and practice

that are culturally meaningful and relevant.

It is ironic that, despite the emphasis of sikolohiyang Pilipino

on identity and consciousness, no empirical investigation of Filipino

national identity from an indigenous psychological perspective

has been done. The present study is an attempt to bridge this

gap. Specifically, the study aimed to: a) surface meanings that

participants associate with the term "Filipino"; b) explore their

bases for defining the Filipino; c) examine the notions of "being

Filipino"; and d) identify persons and contexts that shape their

ideas and beliefs about being Filipino.

METHODOLOGY

In this study, I utilized a qualitative approach since I found

this approach most consistent with the indigenous psychology

perspective. In qualitative research, the wholeness of experience

is valued and the discovery of meaning and relevance is prioritized.

23

I employed the ginabayang talakayan (GT) or facilitated discussion,

an indigenous research method that is frequently used in the

elaboration of issues or concepts (such as the concepts of

pagkalalake at pagkababae in Pe-Pua, Aguiling-Dalisay, & Sto.

Domingo, 1993), or in the collective analysis of problems, and

decision-making (Galvez, 1988). In this research, I used the GT

mainly to surface the meanings attached by the participants to

the concept of being Filipino. Similar to the focus groups, the

collective nature of the GT method also moves away from

psychology's "essentially individualistic framework" (Puddifoot,

1995).

Participants

Thirty-six undergraduate students (18 males and 18 females)

from the University of the Philippines Diliman participated in the

study. UP was chosen since it has a diverse undergraduate student

population base, with a number of students coming from

geographic locations outside Metro Manila and Luzon.

The participants represented six cultural groupings: Metro

Manila and Batangas (Luzon); Iloilo and Cebu (Visayas); and

Christians and Muslims (Mindanao). I approached different student

organizations in order to identify and recruit potential participants.

Aside from these, they were also recruited based on the following

criteria: 1) both parents were Filipinos; 2) born, raised and

currently residing in the Philippines; 3) finished elementary and

secondary education in their home regions or provinces; and 4)

undergraduates at the time of study.

The mean age of the participants is 19.47 years. More than

half are products of private schools: elementary (77.8%) and

secondary (63.9%). Majority of the participants (86.1%) reported

using two to five languages, with Filipino as the most used

language (97.2%).

24

Procedure

Each GT is composed of three to five participants. I served as

the facilitator for all the six GTs. I used a guide written in Filipino

in facilitating the discussions, which I presented to every group

at the start of the GT for approval. .I also asked their permission

to record our discussions. Before we started, I explained to the

participants the purpose of the research and the details of the GT

process. I emphasized to each group that they have the prerogative

to steer the discussion in the direction and pace that they desired.

The discussions took place in the participants' accustomed

environments, usually in their tambayans (student nooks) or in

empty classrooms in the campus. The sessions usually lasted

from one to one and a half hours. At the end of every discussion,

I asked the participants about the process and thanked each one

for their time and contributions.

All the discussions were transcribed and the transcripts were

the bases of my analysis. I coded bits of information that I deemed

important. I gave particular attention to "indigenous concepts,"

or terms used by the participants to label their experiences,

feelings or thoughts (Patton, 1990). I then organized the coded

information into categories or themes. I also looked for similarities

and differences across cultural groupings. I also took note of

illuminating or exemplary quotes from the participants.

After the analysis, I attempted to present the findings to the

participants, but I was not able to re-convene all the groups for

such a purpose. I was only able to gather the Metro Manila

participants for the validation .phase.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

I would like to share an interesting observation that I have

made as I posed my initial questions to the groups. While the

participants gave immediate replies to the question "Are you a

Filipino>," an uncertain silence usually prevailed when I asked

them: "Why do you say so?" Some gave me incredulous and

confused stares as if telling me that I should know the answer

25

to that question since all of us were Filipinos. Some stated that

it is easier to answer the question if a foreigner has asked it. This

stance revealed to me what Jackson and Penrose (1993) wrote

about the concept of 'race' and 'nation' as being:

"...so rooted in the way we think about the world that we tend to take

the categories themselves for granted. {emphasis mine!

D

The term "taken for granted" does not mean that the notion

of being Filipino is unimportant. On the contrary, the participants

found their "Filipino-ness" an important aspect of their social

identity. This was similar to the findings of Conaco's (1996) study

on the social identification and identity of college students. One

participant from Manila remarked:

"Kapag tinanggal sa iyo iyun, hindi mo alam kung saan ka pupunta

o nanggaling. {If it's taken away from you, you wouldn't know where

D

to go or where you have come from"]

Being taken for granted meant that the idea of being Filipino

is usually unexamined, assumed, naturalized, and beyond inquiry

in the context when the people involved in an interaction are

assumed to be all Filipinos. Hence, the question "Are you a

Filipino?" is seen to be more legitimate when it comes from an

outsider. But, in the study, the participants were asked by another

Filipino to explain, examine, reflect on and even challenge their

own ideas about Filipino-ness. This was done in order to discover

how and why the meanings about being Filipino is constructed,

negotiated, and re-constructed.

Loob at Labas (From within and without):

Fllipino as a social category

For the participants, the label "Filipino" is a category that

denotes a specific group of people. Salient in their identification

of features were attributes that separated "Filipinos" from "non-

Filipinos." Thus, it was important for the participants in their

definition of Filipino to delineate members (ingroup) and non-

26

members (outgroup) of the category. This brings to mind Doronila's

(1989) concepts: boundaries of inclusion (loob) and boundaries of

exclusion (labas). The loobjlabas (internatilityjexternality)

dimension has been found to be important in Filipino indigenous

psychology (see Alejo, 1990; Enriquez, 1994; Miranda, 1989).

Qualitative analysis of these boundaries revealed three

important themes: pinaqmulan, (socio-political dimension);

kinalakhan, (cultural dimension); and kamalayan, (psychological

dimension). Figure 2 represents these three dimensions.

Pinagmulan Kinalakhan

Kamalayan

Figure 2. The dimensions of being Filipino

The first cluster of responses has something to do with the

following: being born in the Philippines, having parents who are

Filipinos, residing in the Philippines, is a Filipino citizen.

Collectively, I referred to this cluster as "piruupnulan" (socio-political

origins), which corresponds to a socio-political dimension. This'

dimension corresponds to the narrow definition of citizenship as

stated in the 1987 Constitution.

The second theme, which I termed "kinalakhan" (cultural roots),

revolves around participation and being immersed in a cultural

milieu acknowledged as Filipino. The features identified in this

cluster relate to ideas that identifies Filipinos from foreigners,

which Moerman (1974) termed as "ethnic identification devices."

27

The salient features in this cluster include speaking of a Philippine

language, and to a variety of beliefs and practices the participants

termed as diskarte (loosely, approach or strategy). The diskarte

concept is a fascinating one since I have heard the present

generation of young Filipinos use it in a variety of contexts (see

Tan, 1997). In this study, Ima, a Manila participant, defined

diskarte as:

athe way we see things, the way we look at things at saka paano natin

pine-face yung bawat sitwasyon na mc-encounzer." land how we [ace

every situation that we encounter]

Further exploration of the concept revealed two contexts of

meanings. The first referred to cultural behavior, which is

reminiscent of Jocano's (1997) asal. The second indicated a values

component, which Jocano termed as halaga. In this respect,

diskarte would refer to asal and halaga that the participants

viewed as identifiably Filipino.

The last cluster is what I called "kamalayan" (consciousness].

The responses in this dimension are associated with awareness

of the self as Filipino, acceptance of membership in the category

"Filipino", and also pride in this membership. I called it the

psychological dimension, following Enriquez (1977):

"Filipino identity is not static; a Filipino's self-image as a Filipino can be

as varied as his background; it goes without saying that all Filipinos (Ire

alike regardless of all these, his consciousness of being a Filipino

psychologically define him as one no matter how he sees and defines

the Filipino."

These stated boundaries become significant not only for

identifying others who are part of the loob or labas of the category

Filipino, but also for identifying the self as loob or labas.

Interestingly, it was found that adolescents residing in the United

States who self-identified as Filipinos provided bases that could

be clustered using the same dimensions (Protacio-Marcelino, 1996).

I considered the similarities as suggestive of a shared definition

28

of the label "Filipino" among those who are members of the

category. Conaco (1996) also observed the same tendencies in

Filipino students in her study. Thus, the dimensions may be

considered as part of the participants' social representations of

being Filipino. Also, the dimensions reflect the participants' idea

of a prototypical (stereotypic) Filipino.

While there was a seeming consensus in the content of Filipino

identity, I also found that the salience regarded for each dimension

varied across individuals and cultural groupings. The different

groups tended to highlight certain dimensions and aspects of the

representations that they considered as integral to being Filipino

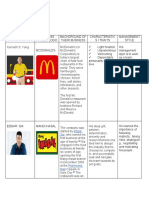

(see Table. 1).

Table 1. Dimensions and aspects of Filipino identity considered as integral across participant

groups

Group Dimension Aspects

Manila Kamalayan Pride in being a Filipino

Batangas Kinalakhan . Language

Cebu Kamalayan Awareness and acceptance

of self as Filipino

Iloilo Kinalakhan Cultural practices

Christians from Mindanao Kinalakhan Cultural practices

Muslims from Mindanao Plnagmulan Being a citizen of the Philippines

Participants from Manila and Cebu had a tendency to

emphasize the consciousness dimension while Batangas, Iloilo

and Mindanao Christian participants considered the cultural

aspects as most important. Meanwhile, the Muslim participants

regarded their citizenship as the only important criterion for being

a Filipino.

I also looked into aspects that the participants considered as

non-integral in their definitions of being Filipinos. The responses

were revealing. Manila and Cebu participants regarded the

proficiency in Filipino as non-integral in their idea of a Filipino

while Muslim referred to cultural beliefs, traditions and practices

as unimportant in their classification.

29

What do these findings suggest? Conaco (1996) interpreted

this heterogeneity as identity confusion among her stUQY

participants. However, I am more inclined to favor the motivational

aspect of self-categorization by Abrams and Hogg (1990):

aWeare driuen to represent the context dependent social world, including

the self, in terms of categories which are most accessible to our cognitiue

apparatus and which best fit releuant, i.e., subjectiuely important, useful;

meaningful, similarities and differences in stimulus domain. D

The similarities in the themes or dimensions represent those

ideas that are most accessible to the participants' cognitive

apparatus (the idea of a prototypical Filipino). However, the

differences accorded to the salience of each dimension reflect the

attempts by the participants to select which are subjectively

important. In the case of Manila and Cebu participants, the fact

that by their own admission, their language, ideologies and

practices are more American-oriented did not prevent them from

categorizing themselves as loob by highlighting the consciousness

dimension (acceptance of and pride in being a Filipino). Meanwhile,

the Muslim participants regarded themselves as loob based only

on their membership in the state. They de-emphasized the cultural

dimension largely due to the difference in religion.

This suggests that the participants were motivated to highlight

those dimensions that made them closer to the prototypical Filipino

and to de-emphasize the dimensions that distance them from

this ideal. This could also indicate that the notion of being Filipino

is still a relevant identity among the participants. This finding

echoes the results of Conaco's (1996) study.

Babaw at Lalim (Surface and Depth):

Filipino-ness as an ethical standard

While Filipino represents the social category, "paqka-Pilipino"

(being Filipino or Filipino-ness) denotes an evaluative aspect of

being a member of that social group. Filipino-ness refer to the

quality of being Filipino. From the discussions, two levels of

30

Filipino-ness (qualities) were identified by the participants. I used

the labels that the participants actually used in the discussions:

"Pilipino sa pangalan" (Filipino in name or nominal Filipino), and

"Pilipino sa puso" (Filipino by heart).

When asked to define what they meant by Pilipino sa

II

pangalan", the features enumerated by the participants

corresponded to an image of a passive citizen. This individual

may accept or recognize that he or she is a Filipino but may not

be involved in activities that highlight the identity.

According to Covar (1995), the kind of puso one has signifies

the strength of one's personal conviction. In this sense, a "Pilipino

sa puso" is someone who considers Filipino-ness a conviction -,

(pananindigan). Thus, the use of the term Pilipino sa puso"

II

suggests that Filipino-ness has become internalized or integrated

with the loob.. In the previous section, loob/Iabas was used in the

context of category membership. In this section, loob refers to

those ideas that are deemed important and relevant in relation to

the .self, while labas may be considered as irrelevant and

unimportant. While it is appropriate to assume that Pilipino sa

II

puso" have deemed their Filipino-ness as loob and thus, an

important aspect of their identity, it may be too hasty to say that

Filipino-ness is labas and therefore irrelevant among "Pilipino sa

pangalan."

I would argue that nominal Filipinos, due to a recognition of

the self as Filipino, also makes Filipino-ness a part of their loob.

However, there seems to be a qualitative difference or gradation

of this kind of integration into the loob.Again, I turned to Covar

(1995) for some answers. He used a Manuvu jar as a metaphor

for Filipino personhood. According to him, it has three elements:

loob, labas and lalim (depth). While Covar used lalim as a distinct

aspect of pagkatao, I used lalim to signify the gradation of

integration into the loob. Thus, Pilipino sa pangalan would imply

a superficial (mababaw) integration and Pilipino sa puso would

suggest a deeper (malalim) integration into the loob.

How would we know if Filipino-ness is superficial or not?

Based on Miranda's (1989) formulation, loob has galaw:

31

"Galaw is the person-al and person-alizing category. Man is personal

and personalized in his galaw, as that pagitan between his loob and his

labas, be it realized in kilos or concretized in gawa.

In this sense, the difference in Pilipino sa pangalan and Pilipino

sa puso lie in the activity (galaw) of the loob or the lack of it.

Since Filipino-ness is deeply integrated in a Pilipino sa puso's

loob then it has become personal and personalized, which can

only be realized in kilos (behavior) and concretized in qauia (habit).

Thus, the loob's galaw is recognized only when it is manifested

in the labas since: "Loob can manifest itself only through some

form of externalization" (Miranda, 1989).

Thus, a Pilipino sa puso can only be recognized through his

or her actions. Jayson, a participant from Batangas, expounds:

"Paranq hindi lang pina-practice yung pagiging Pilipino, nag-aaral siya

sa mga kultura sa Pilipinas. Inaalam niya yung pamumuhay ng i/;lang

tao, hindi lang iyong malalapit sa kaniya, parang gumagamit pa siya ng

oras para lang matutunan niya yung kultura ng Pilipinas D

does not

{ ...

only practice being a Filipino, he also studies the culture. He investigafes

the way of life of other people, not only those who are closest to him.

This comes to a point that he devotes a certain amount of time in

studying Filipino culture]

The following summarizes other responses by the participants

as part of the galaw of Pilipino sa puso.

Recognizes and accepts the self as Filipino'

Takes pride in being Filipino Recognizes and accepts fellow

Filipinos'

Has empathy for fellow Filipinos'

Involved in the affairs of fellow Filipinos

The Filipino-ness of Pilipino sa pangalan is also manifested

through the galaw of their loob. Table 2 summarizes the differences

between Pilipino sa pangalan and Pilipino sa puso in terms of

galaw.

32

Table 2. Differences between Pilipino sa pangalan and Pilipino sa puso

Kinds of Filipino-ness Level of integration Manifested "galaw"

into the Loob

Pilipino sa panga/an . Mababaw (superficial) Recognition and Acceptance

of self as Filipino

Pilipino sa puso Malalim(deep) Conviction in self as Filipino

I have noticed that Filipino-ness is not simply a description

of behaviors associated with those who identify as Filipinos. It

was very clear in the discussions, especially among Manila and

Cebu participants, that some individuals' Filipino-ness is better

than others. Thus, the idea of Filipino-ness invokes some sort of

an ethical standard of being Filipino.

Filil?ino-ness is the identity's performative aspect. The

performative is the. element that bring impetus to personhood

(Tolentino, 2001). In order for an identity to be validated, it has

to be performed. Through performance, the identity is rehearsed

and strengthened.

What is the relationship of Filipino-ness (identity position) to

the dimensions of being a Filipino (representation)? By examining

the manifested galaw of both identity positions, it seems that

level of consciousness (kamalayan) serves as the primary criterion

of determining identity position. High level means deeper

integration (Pilipino sa puso) while low level consciousness (Pilipino

sapangalan) may account for superficial integration.

SYNTHESIS AND CONCLUSIONS

The label "Filipino" functions as a social category. And as

such, it is important to identify its boundaries. The meaningful

boundaries define the loob/labas of the concept of Filipino. Identity

as Filipino was found to have three relevant components:

pinagmulan (socio-political component); kinalakhan (cultural

component); and kamalayan (psychological component). This

33

supports the position that national identity is more than a political

identity. It is possible to think of national identity as three kinds

of relationships: relationship with the state; relationship with

culture; and relationship with self and others. Also, the

extensiveness of the three themes across the cultural groups

denotes that these dimensions make up the representation of a

prototypical Filipino.

However, the more interesting finding is that individuals and

groups place differing emphases on the three dimensions. One

possible explanation would be is that they are motivated to

highlight dimensions that make them similar to this prototype

and at the same time, de-emphasize the characteristics that make

them dissimilar from this prototype. This suggests that the national

identity as Filipino is important. However, the analysis did not

provide an explanation for such a motivation. Would the desire

to be similar to the prototypical Filipino imply, as social identity

theory would suggest, that the Filipino as a social category has

attained a positive status in the eyes of the participants?

Unfortunately, this is beyond the study's scope.

Another important implication is that it reveals the

constructed-ness of our national identity. Our notion of being

Filipino is negotiated and not fixed. This means that our definitions

of being Filipino have the potential to be changed depending on

a variety of factors: gender, ethnicity, age, political convictions,

background, upbringing among others. True, this flexibility may

bring about more confusion about our national identity but ona

more positive note, this could also provide maneuverable spaces

for marginalized groups to participate in a national context:

Chinese-Filipinos, Amerasians and other biracials in the

Philippines; naturalized citizens; indigenous peoples; and non-

Christian groups.

Last, the analysis identified two kinds of Filipino-ness. This

is based on the level of identity integration into one's loob.

A more integrated sense of Filipino identity is called "Pilipino sa

puso". The individual who has not fully integrated this sense of

being Filipino into the self is known as ..Pilipino sa pangalan."

34

Kamalayan (psychological sense) seems to be the primary

determining factor of Filipino-ness. There is a need to explore the

function of the other two dimensions in determining identity

positions. How do differing emphases on the dimensions impact

on the resulting identity positions?

In this study, the relationship between representation and

identity position has been explored in the context of Filipino as

national identity. It was clear that both the social context and

individual subjectivity play significant roles in the direction with

which Filipino identities could take shape.

REFERENCES

Abrams, D. & Hogg, M. (1990). Social identity theory: Constructive

and critical advances. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Alejo, A. (1990). Tao po! Tuloy! Isang landas ng pag-unawa sa loob

ng tao. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

Anttila, J. (1997). Kansallisen identifioitumisen motiiviperustaa

etstmaessaey Motives for identification with a nation.

Psykologia, 32(2), 84-92.

Azurin, A. (1995). Reinventing the Filipino sense of being and

becoming. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Cassidy, C. & Trew, K. (1998). Identities in Northern Ireland:

A multidimensional approach. Journal of Social Issues, 54 (4);

725-740.

Cipres-Ortega, S. (1984). The development of social-psychological

concepts among children. Unpublished masters thesis,

University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City.

Conaco, M.C.G. (1996). Social categorization and identity in the

Philippines. Professorial Chair Paper Series No. 96--12. Quezon

City: CSSP Publications.

Constantino, R. (1969). The making of a Filipino: A story of

Philippine colonial politics. Quezon City: Malaya Books.

35

Covar, P. (1995). Unburdening Philippine society of colonialism.

Diliman Review 43(2), 15-20.

Doronila, M.L. (1982). The limits of educational change. Quezon

City: University of the Philippines Press.

Doronila, M.L. (1989). Some preliminary data and analysis Of the

content and meaning of Filipino national identity among urban

Filipino schoolchildren: Implications to education and national

development. Education Resource Center Occasional Paper.

Quezon City: Center for Integrative and Development Studies.

Doronila, M.L. (1992). National identity and social change. Quezon

City: University of the Philippines Press and the Center for

Integrative and Development Studies.

Du Gay, P., Hall, S., Janes, L., Mackay, H. & Negus, K. (ed.)

(1997). Doing cultural studies: The story of the Sony Walkman.

London: Sage/The Open University.

Enriquez, V.G. (1976). Sikolohiyang Pilipino: Perspektibo at

direksiyon. Ulat ng Unang Pambansang Kumperensiya sa

Sikolohiyang Filipino. Quezon City: Pam bansang Sarnahan sa

Sikolohiyang Pilipino.

Enriquez, V.G. (1977). Filipino psychology in the Third World.

Philippine Journal of Psychology, 10 (1); 3-18.

Enriquez, V.G. (1994). From colonial to liberation psychology: The

Philippine experience (International Edition). Manila: De La

Salle University Press.

Galvez, R. (1988). Ang ginabayang talakayan: Katutuborig

pamamaraan ng sama-samang pananaliksik. In R. Pe-Pua

(Ed.), Mga piling babasahin sa panlarangang pananaliksik II.

Quezon City: UP Department of Psychology.

Jackson, P. & Penrose, J. (1993). Introduction: placing "race" and

nation. In P. Jackson & J. Penrose, Constructions of race,

place and nation (pp. 1-23). Minnesota: University of Minnesota

Press.

36

Jocano, F.L. (1997). Filipino value system. Anthropology of the

Filipino People II. Metro Manila: Punlad Research House, Inc.

Miranda, D. (1989). Loob: The Filipino within. Manila: Divine Word

Publications.

Moerman, M. (1974). Accomplishing ethnicity. In R. Turner (Ed.),

Ethnomethodology. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Patton, M. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods

(2n d Ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Pe-Pua, R., Aguiling-Dalisay, G. & Sto. Domingo, M. (1993).

Pagkababae at pagkalalaki: Tungo sa pag-unawa sa

sekswalidad ng mga Pilipino. Diuia, 10(1-4), 1-8.

Protacio-Marcelino, E. (1996). Identidad at etnisidad: Karanasan

at pananaw ng mga estudyanteng Filipino Amerikano sa

California. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of

the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City.

Puddifoot, J. (1995). Dimensions of community identity. Journal

of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 5, 357-370.

Salazar, J.M. (1998). Social identity and national identity. In S.

Worchel, J. F. Morales, D. Paez & J.C. Deschamps (eds.),

Social identity: International perspectives (114-123). Thousand

Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc ..

Sinha, D. (1997). Indigenizing psychology. In J.W. Berry, Y.

Poortinga, & J. Pandey (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural

psychology. Vol. I: Theory and method (129-1.69). Boston: Allyn

and Bacon.

Tajfel, H. (1969). The formation of national attitudes: A social

psychological perspective. In M. Sherif &. C. Sherif (Eds.),

Interdisciplinary relationships in the social sciences. Chicago:

Aldine.

37

Tajfel, H. (1970). Aspects of national and ethnic loyalty, Social

Science Information, 9, 119-144.

Tan, M. (19971. Love and desire: Sexual risk among Filipino young

adults. Quezon City: UP Center for Women's Studies.

Tolentino, R. (2001). Sa loob at labas ng mall kong saun/Kaliluha'u

siyang nangyayaring hari: Ang pagkatuto at paqtatanqhal ng

kulturang popular. Quezon City: University of the Philippines

Press.

-

You might also like

- Making Sense of Our Being and Becoming A PDFDocument18 pagesMaking Sense of Our Being and Becoming A PDFJilian Mae Ranes OrnidoNo ratings yet

- Fil PsychDocument4 pagesFil Psychma.raisa.quilantang.20No ratings yet

- Project in Filipino Psychology MaryGenDocument16 pagesProject in Filipino Psychology MaryGenmgbautistallaNo ratings yet

- Filipino Psychology JournalDocument56 pagesFilipino Psychology JournalRachel TangNo ratings yet

- Social Categorization and Identity in The PhilippinesDocument10 pagesSocial Categorization and Identity in The PhilippinesJinky AlzateNo ratings yet

- Yacat2005 SummaryDocument3 pagesYacat2005 SummaryHannah MondillaNo ratings yet

- ReportingDocument60 pagesReportingJon Teodulo NiervaNo ratings yet

- 5 Pe-Pua Rogelia (2018) - Unpackaging The Concept of Loob in Handbook of Filipino Psychology Vol. 1 p.382-394Document17 pages5 Pe-Pua Rogelia (2018) - Unpackaging The Concept of Loob in Handbook of Filipino Psychology Vol. 1 p.382-394kuyainday123No ratings yet

- FILPSYCH IndigenizationDocument11 pagesFILPSYCH IndigenizationAngel Shayne C. PeñeraNo ratings yet

- Eduarte - Filpsy 6Document11 pagesEduarte - Filpsy 6Eduarte, IanNo ratings yet

- Divina D. Laylo - Final Paper - SSM114Document6 pagesDivina D. Laylo - Final Paper - SSM114DIVINA DELGADO-LAYLONo ratings yet

- Sikolohiyang Pilipino (SIKOPIL) Syllabus (Filipino Psychology)Document25 pagesSikolohiyang Pilipino (SIKOPIL) Syllabus (Filipino Psychology)paytencasNo ratings yet

- PePua Marcelino 2000Document23 pagesPePua Marcelino 2000Stacy ArrietaNo ratings yet

- Filipino Psychology Concepts and MethodsDocument116 pagesFilipino Psychology Concepts and MethodsEllia Waters100% (1)

- SHS - Diss - Q2 - Las2 FinalDocument4 pagesSHS - Diss - Q2 - Las2 FinalPaige Jan DaltonNo ratings yet

- Lecture Notes in Culture and Filipino Psychology The Filipinization of Personality Theory EncodedDocument20 pagesLecture Notes in Culture and Filipino Psychology The Filipinization of Personality Theory EncodedHannah MondillaNo ratings yet

- Filipino PsychologyDocument9 pagesFilipino PsychologykimNo ratings yet

- Asian J of Social Psycho 2002 PePua Sikolohiyang Pilipino FilipinoDocument23 pagesAsian J of Social Psycho 2002 PePua Sikolohiyang Pilipino FilipinoMichelle Anne P. GazmenNo ratings yet

- Indigenization of Psychology in The PhilippinesDocument21 pagesIndigenization of Psychology in The PhilippinesGeraldYgayNo ratings yet

- History of Phil. PsychologyDocument23 pagesHistory of Phil. PsychologyEureka Irish Pineda Ebbay75% (4)

- Filipino Psychology - Concepts and MethodsDocument116 pagesFilipino Psychology - Concepts and MethodsRoman Sarmiento70% (10)

- Filipino PsychologyDocument9 pagesFilipino Psychologyjimbogalicia100% (2)

- Sikolohiyang Pilipino PDFDocument19 pagesSikolohiyang Pilipino PDFVince Clark PatacayNo ratings yet

- Philippines I 765 783 PDFDocument19 pagesPhilippines I 765 783 PDFrhiantics_kram11No ratings yet

- Critical Psychology in Changing World SiDocument19 pagesCritical Psychology in Changing World SiDave MatusalemNo ratings yet

- Summary of SikoPilDocument9 pagesSummary of SikoPilKyra RMNo ratings yet

- Intro To SikoPilDocument9 pagesIntro To SikoPilJas BNo ratings yet

- Filipino PsychologyDocument9 pagesFilipino PsychologySu Kings AbetoNo ratings yet

- Sugboanong' Taras: A Glimpse of Cebuano Personality: June 2016Document23 pagesSugboanong' Taras: A Glimpse of Cebuano Personality: June 2016Aira VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Filipino PSychopathology (2022-23)Document11 pagesFilipino PSychopathology (2022-23)laiNo ratings yet

- Filipino PsychologyDocument34 pagesFilipino Psychologykristel.maghacotNo ratings yet

- Filipino Psychology ReviewerDocument15 pagesFilipino Psychology ReviewerGraceLy Mateo100% (1)

- Lesson 2-3 Sikolohiyang PilipinoDocument23 pagesLesson 2-3 Sikolohiyang PilipinoMaricris Gatdula100% (1)

- Filipino Psychology in The Third World PDFDocument18 pagesFilipino Psychology in The Third World PDFMelissaNo ratings yet

- Intro To SikoPilDocument8 pagesIntro To SikoPilmeNo ratings yet

- Geoup 6 Compiled ReportsDocument8 pagesGeoup 6 Compiled ReportsSierra Felecia RiegoNo ratings yet

- Filipino PsychologyDocument33 pagesFilipino PsychologyJirah MarcelinoNo ratings yet

- Sikfil ReviewerDocument6 pagesSikfil ReviewerBarrientos Lhea ShaineNo ratings yet

- Filipino Psychology: Filipino Filipinos Pambansang Samahan Sa Sikolohiyang Pilipino Virgilio EnriquezDocument7 pagesFilipino Psychology: Filipino Filipinos Pambansang Samahan Sa Sikolohiyang Pilipino Virgilio EnriquezCrizzle Jasmine Quintinita CardenasNo ratings yet

- Indigenization of Psychology PDFDocument16 pagesIndigenization of Psychology PDFThea Silayro0% (1)

- SAS - Session-5 - Indigenous - Psychology (GRACIA)Document6 pagesSAS - Session-5 - Indigenous - Psychology (GRACIA)Frany Marie GraciaNo ratings yet

- Discipline and Ideas in The Social Sciences 2 QuarterDocument8 pagesDiscipline and Ideas in The Social Sciences 2 QuarterMarianne80% (5)

- Filipino Psychology Filipino Psychology Concepts and Methods Concepts and MethodsDocument186 pagesFilipino Psychology Filipino Psychology Concepts and Methods Concepts and MethodsJas BNo ratings yet

- The Development of A Filipino Indigenous PsychologyDocument4 pagesThe Development of A Filipino Indigenous PsychologyMaria Divina Santiago0% (1)

- Reviewer Sa SikpilDocument7 pagesReviewer Sa SikpilHannah Faye InsailNo ratings yet

- NotesDocument8 pagesNotesTEOFILO PALSIMON JR.No ratings yet

- Mendoza Pantayong Pananaw EnglishDocument60 pagesMendoza Pantayong Pananaw EnglishLorenaNo ratings yet

- Module 1Document11 pagesModule 1Rose MaNo ratings yet

- Key Concepts and Ideas of Filipino Thinkers in The Social SciencesDocument6 pagesKey Concepts and Ideas of Filipino Thinkers in The Social Sciencesshiella mae baltazar94% (16)

- The Hybrid Tsinoys: Challenges of Hybridity and Homogeneity as Sociocultural Constructs among the Chinese in the PhilippinesFrom EverandThe Hybrid Tsinoys: Challenges of Hybridity and Homogeneity as Sociocultural Constructs among the Chinese in the PhilippinesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Rebranding Islam: Piety, Prosperity, and a Self-Help GuruFrom EverandRebranding Islam: Piety, Prosperity, and a Self-Help GuruNo ratings yet

- Difference and Sameness as Modes of Integration: Anthropological Perspectives on Ethnicity and ReligionFrom EverandDifference and Sameness as Modes of Integration: Anthropological Perspectives on Ethnicity and ReligionNo ratings yet

- Pedagogy of the Oppressor: Experiential Education on the US/Mexico BorderFrom EverandPedagogy of the Oppressor: Experiential Education on the US/Mexico BorderNo ratings yet

- A World of Many: Ontology and Child Development among the Maya of Southern MexicoFrom EverandA World of Many: Ontology and Child Development among the Maya of Southern MexicoNo ratings yet

- Nation, Self and Citizenship: An Invitation to Philippine SociologyFrom EverandNation, Self and Citizenship: An Invitation to Philippine SociologyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- UNESCO on the Ground: Local Perspectives on Intangible Cultural HeritageFrom EverandUNESCO on the Ground: Local Perspectives on Intangible Cultural HeritageNo ratings yet

- Universalism without Uniformity: Explorations in Mind and CultureFrom EverandUniversalism without Uniformity: Explorations in Mind and CultureJulia L. CassanitiNo ratings yet

- Organizational StructuresDocument13 pagesOrganizational StructuresJangNo ratings yet

- MfatspeechDocument5 pagesMfatspeechChirasree DasguptaNo ratings yet

- M ScottPeckDocument9 pagesM ScottPeckJangNo ratings yet

- Brown's Values-Based Theory Career GuidanceDocument7 pagesBrown's Values-Based Theory Career GuidanceJang100% (2)

- Guidance and CounselingDocument25 pagesGuidance and CounselingJangNo ratings yet

- K To 12 BasicDocument27 pagesK To 12 BasicJangNo ratings yet

- Theory On Work Adjustment Report Career GuidanceDocument13 pagesTheory On Work Adjustment Report Career GuidanceJangNo ratings yet

- Pastoral CounselingDocument13 pagesPastoral CounselingJangNo ratings yet

- PlacementDocument26 pagesPlacementJangNo ratings yet

- Brown's Values-Based Theory Career GuidanceDocument7 pagesBrown's Values-Based Theory Career GuidanceJang100% (2)

- Career Dev'tDocument31 pagesCareer Dev'tJangNo ratings yet

- Study HabitsDocument17 pagesStudy HabitsSrihari Managoli100% (4)

- Introduction To PsychologyDocument418 pagesIntroduction To Psychologynortomate100% (2)

- Career CounsellingDocument10 pagesCareer CounsellingJangNo ratings yet

- Guidance and CounselingDocument25 pagesGuidance and CounselingJangNo ratings yet

- Habit 7Document22 pagesHabit 7JangNo ratings yet

- ENFJ Extraverted INtuitive Feeling JudgingDocument3 pagesENFJ Extraverted INtuitive Feeling JudgingJangNo ratings yet

- PlacementDocument26 pagesPlacementJangNo ratings yet

- Organizational StructuresDocument13 pagesOrganizational StructuresJangNo ratings yet

- Brown's Values-Based Theory Career GuidanceDocument7 pagesBrown's Values-Based Theory Career GuidanceJang100% (2)

- Ecological SystemsDocument9 pagesEcological SystemsJangNo ratings yet

- CH 1fghDocument33 pagesCH 1fghJangNo ratings yet

- Disruptivedisorders5 150221194031 Conversion Gate01Document24 pagesDisruptivedisorders5 150221194031 Conversion Gate01JangNo ratings yet

- Holland Ria SecDocument31 pagesHolland Ria SecJangNo ratings yet

- Ethical Issues in Guidance and CounsellingDocument40 pagesEthical Issues in Guidance and CounsellingJangNo ratings yet

- Philosophy, Counseling, and PsychotherapyDocument30 pagesPhilosophy, Counseling, and PsychotherapyCodru Psiho100% (1)

- Guidance Model PDFDocument18 pagesGuidance Model PDFJean Lois Condeza GelmoNo ratings yet

- Career & Advising Services - Economics DepartmentDocument24 pagesCareer & Advising Services - Economics DepartmentJangNo ratings yet

- School Counseling Regs 2012Document93 pagesSchool Counseling Regs 2012JangNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of Teaching LLBDocument2 pagesPhilosophy of Teaching LLBJangNo ratings yet

- Vatican City (C & D)Document3 pagesVatican City (C & D)Natoy NatoyNo ratings yet

- 2021 Customs Broker Licensure Examination ResultsDocument3 pages2021 Customs Broker Licensure Examination ResultsRapplerNo ratings yet

- 9184 or The Government Procurement Reform Act, Requires AllDocument3 pages9184 or The Government Procurement Reform Act, Requires AllKatrina PajelaNo ratings yet

- Art Appreciation - Group1Document41 pagesArt Appreciation - Group1Noemi T. LiberatoNo ratings yet

- Monthly Accomplishment ReportDocument7 pagesMonthly Accomplishment ReportEdna RazNo ratings yet

- Language Diversity and English in The Philippines by Curtis McFarlandDocument23 pagesLanguage Diversity and English in The Philippines by Curtis McFarlandJhy-jhy OrozcoNo ratings yet

- Survey of Philippine Literature in EnglishDocument38 pagesSurvey of Philippine Literature in Englishyoonglespiano100% (1)

- Kenneth S. Yang: Edgar SiaDocument4 pagesKenneth S. Yang: Edgar SiaPark JiminNo ratings yet

- Civil Engineer 05-2017 Room AssignmentDocument28 pagesCivil Engineer 05-2017 Room AssignmentPRC Baguio100% (3)

- The Value and Understanding of The Historical, Social, Economic, and Political Implications of ArtDocument6 pagesThe Value and Understanding of The Historical, Social, Economic, and Political Implications of ArtKraix Rithe RigunanNo ratings yet

- ORNAP-NMC Newsletter (Vol. I Issue 2) - 2011Document2 pagesORNAP-NMC Newsletter (Vol. I Issue 2) - 2011Richard C. OngpoyNo ratings yet

- Filipiniana Reference and Information SourcesDocument24 pagesFilipiniana Reference and Information SourcesGrace CastañoNo ratings yet

- Filipino IngenuityDocument2 pagesFilipino IngenuityKylne Bcd100% (1)

- Template 2019 EnrolmentDocument36 pagesTemplate 2019 EnrolmentMishokie AshieNo ratings yet

- Humss Report-Card-Inside-Page-Grade-11Document1 pageHumss Report-Card-Inside-Page-Grade-11ZINA ARRDEE ALCANTARANo ratings yet

- Disciplines and Ideas in The Social SciencesDocument9 pagesDisciplines and Ideas in The Social SciencesMari Cel100% (2)

- Worksheet (Region 13)Document1 pageWorksheet (Region 13)Katherine MasangcayNo ratings yet

- Module 2Document11 pagesModule 2R-jay RiveraNo ratings yet

- Declaration OF Principles & State Policies: Principles vs. Policies Self-Executing vs. Not Self-ExecutingDocument3 pagesDeclaration OF Principles & State Policies: Principles vs. Policies Self-Executing vs. Not Self-ExecutingRJCenitaNo ratings yet

- Brief History of Science and Technology in The PhilippinesDocument11 pagesBrief History of Science and Technology in The PhilippinesElaine PolicarpioNo ratings yet

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocument2 pagesCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 World HXDocument10 pagesChapter 7 World HXJela Valencia100% (1)

- 10StrengtheningandPreserving 2Document15 pages10StrengtheningandPreserving 2Róy Meñales Jr.No ratings yet

- Prospero Covar Profile and WorksDocument37 pagesProspero Covar Profile and WorksKim0% (1)

- History of MaigoDocument3 pagesHistory of MaigoChezka OllidesNo ratings yet

- 21 Century Literature From The Philippines and The World: Quarter 1-Week 1Document11 pages21 Century Literature From The Philippines and The World: Quarter 1-Week 1Lovely Pitiquen100% (2)

- Manila RA - LET0318 - Math - e PDFDocument91 pagesManila RA - LET0318 - Math - e PDFPhilBoardResultsNo ratings yet

- RMO No. 13-2018annex ADocument2 pagesRMO No. 13-2018annex AChel-chan NiemNo ratings yet

- Mylene RuizDocument3 pagesMylene RuizQ u e e n ツNo ratings yet

- MODULEDocument8 pagesMODULEFrances Nicole SegundoNo ratings yet