Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Language Urn NBN Si Doc MJPBDGML

Uploaded by

Yamith José FandiñoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Language Urn NBN Si Doc MJPBDGML

Uploaded by

Yamith José FandiñoCopyright:

Available Formats

U D K 800.

1:316

James W. Tollefson

Washingtonska univerza, Seattle

L A N G U A G E PLANNING AND SOCIAL T H E O R Y

Novoklasini in zgodovinskostrukturalni pristop k raziskovanju jezikovnega nartovanja se protista-

vita glede na e n o t o analize, vlogo zgodovinske analize, namen vrednotenja in implicitno ideologijo.

T h e neoclassical and the historical-structural approach to language planning research are contrasted

with reference to the unit of analysis, the purpose of evaluation, and implicit ideology.

Research in the field of language planning seeks to describe and explain

deliberate efforts to change language structure and language use. Its emphasis is on

p l a n n e d change, as distinct from unplanned or "natural" language change.

Research in this area has focused upon such issues as language standardization;

language acquisition and loss; development of writing systems, normative gram-

mars, and dictionaries; linguistic modernization, including development of scienti-

fic and technological terminology; and efforts to use vernaculars in education and

government. A m o n g the major questions in language planning are: U n d e r what

conditions will specific changes in language structure be accepted by a speech

community? When will vernacular languages be considered acceptable as official

languages of government and education? What kinds of policies will effectively

regulate language use within bilingual and multilingual speech communities? H o w

might languages be codified or standardized?

Since the field of language planning began to take shape in the 1960s, the

amount of published material has grown so rapidly that there are now journals (e.

g., Language Problems and Language Planning published at the University of

Texas), an introductory textbook ( E a s t m a n , 1983), theoretical essays (e. g., Rubin

and J e r n u d d , 1971), and h u n d r e d s of case studies (see Lencek 1971; Fishman

1974). A m o n g the most important international conferences on language planning

was the Ljubljana Seminar on the Multinational Society, convened by the United

Nations Secretariat, J u n e 8 - 2 1 , 1965 (for the collected papers, see Mackey and

V e r d o o d t 1975).

Despite the large and growing literature on language planning, attempts to

synthesize the field into a comprehensive theoretical framework have proved to be

inadequate. T h e most important difficulties in this effort are the lack of compara-

ble methodologies of empirical studies, the trivial nature of many generalizations,

the irrelevance of much of research to actual language planning processes, and the

isolation of language research f r o m related issues of social planning.

A central aspect of these limitations is the coexistence of two competing

analytical approaches. Research within the n e o c l a s s i c a l framework presumes

that the rational calculus of individuals is the proper focus of language planning

research. In this view, the formulation of language plans and policies involves

rational analysis of the costs and benefits of alternatives; the implementation of

plans and policies consists of distributing these costs and benefits in a m a n n e r

designed to achieve formulated goals; and the evaluation of plans and polices

consists of quantitative measures of the "fit" between stated goals and achieved

ends. T h e neoclassical approach contrasts with the h i s t o r i c a l - s t r u c t u r a l

approach developed primarily for application to language problems in developing

nations (cf W o o d 1982). T h e historical-structural approach examines the history of

the social system within which planning takes place, with primary emphasis upon

structural considerations (e. g., class). T h e historical-structural approach searches

for the origin of constraints on planning; the sources of the costs and benefits of

alternatives; the relationship between language planning and other areas of social

planning; and the social, political, and economic factors that constrain or impel

changes in language structure and use.

T h e differences between research within the neoclassical approach and research

within the historical-structural approach involve the unit of analysis each employs,

the role of historical analysis, and the purpose of evaluation in the planning

process. These differences are reviewed and critiqued in part one of this article.

These conceptual issues reflect more f u n d a m e n t a l differences between the two

f r a m e w o r k s . These more f u n d a m e n t a l differences involve the underlying ideologi-

cal orientation of the p r o p o n e n t s of the two approaches and their different views of

the relative importance of individual choice and collective behavior in social

science research. T h e impact of these differences on the development of language

planning theory is examined in the second part of this article.

Part I - Competing Analytical A p p r o a c h e s

T h e Neoclassical Model of Language Planning

In the neoclassical model of language planning, the language planning process

is conceptualized as the formulation and implementation of plans according to

a rational analysis of the costs and benefits of alternatives (Jernudd and Das G u p t a

1971; T h o r b u r n 1971). O n e particularly important set of costs includes difficulties

encountered in implementation. It is assumed that successful implementation

requires accurate and comprehensive analysis of potential difficulties as part of the

formulation of plans and policies. Political organization and economic structures

are viewed as the setting within which plans are formulated and as possible sources

of difficulties for plan implementation. It is presumed that plans and policies

reflecting the needs and goals of the sociopolitical system will be more easily

implemented than those that run counter to those needs and goals. Thus it is widely

claimed that plans and policies should conform to the general drift of social forces if

they are to be successful. It is presumed further that language is a resource like any

other resource, that language thus has quantifiable economic value, and that its

economic value is a central c o m p o n e n t in the rational assessment of costs and

benefits of alternative plans (Fishman, D a s G u p t a , J e r n u d d , and Rubin 1971).

T h e neoclassical f r a m e w o r k presupposes that planners seek to formulate and

implement plans that will provide the greatest return (i. e . , maximum net benefits

after costs). T h e f r a m e w o r k also presupposes that plans and policies are the

cumulative result of individual decisions about the costs entailed and the benefits to

be gained from alternatives. In its broadest form, this f r a m e w o r k is an example of

the neoclassical micro-economic theory of consumer choice (Shaw 1975). T h e

model has b e e n extended to include variables such as the costs and benefits to

specific agents responsible for planning (Jernudd 1971), the processes by which

costs and benefits are distributed within the political system (Pool 1972), the role of

evaluation in planning (Rubin 1971; J e r n u d d 1983), and the impact of ethnicity,

nationality, and religion ( D a s G u p t a 1970). T h e model has been further extended

by applying it to nation building (Barnes 1977), economic development (Hoevar

1982), and international relations (Alisjahbana 1974).

T h e Historical-Structural Model of Language Planning

Both corpus planning (i. e . , changes in language structure) and status planning

( i . e . , changes in the social or political role of languages) are carried out within the

context of broader economic and social planning. This means that the benefits of

plans often accrue with reference to economic and sociopolitical aims. For in-

stance, the status planning decision in the United States to expand the functional

range of Spanish to include the exercise of voting is analyzed within the neoclassical

f r a m e w o r k as a cost expended in order to achieve the benefits of increased political

participation of the Spanish-speaking community and its greater commitment to

the English-dominant political system. In contrast, within the historical-structural

a p p r o a c h , research seeks to discover the mechanisms that perpetuate existing class

structure and exploitation, as well as the contradictory tendencies that lead to

structural transformation (Bach and Schraml 1982). Though this approach permits

a wide range of viewpoints, the primary insights have been derived from Marxist

analysis.

Within the historical-structural approach, the language planning process is

viewed as one arena within which the interests of dominant groups are maintained

and the seeds of transformation are developed. T h u s the m a j o r goal of language

planning research is to examine the historical basis for planning processes and to

make explicit the mechanisms by which language planning decisions serve or

undermine particular class interests. Language planning institutions are viewed as

being inseparable from the political economy, and no different from other class-

based structures.

In contrast to the neoclassical model, the historical-structural model assumes

that the primary goal of research and analysis is to discover the historical and

structural pressures that lead to particular policies and plans. Structural factors

influence language planning decision through their impact on the composition of

planning bodies and on the economic interests which are expressed by the

sociopolitical goals to which those bodies are committed. Thus language planning is

considered a macro-social rather than a micro-social process (Tollefson 1981b).

Moreover, language planning is conceptualized as a historical process inseparable

f r o m structural considerations, particularly the class-based political system. T h e

unit of analysis is thus the historical process as opposed to the neoclassical

approach, which examines individual decisions.

Explanations for planning decisions may refer to a wide range of historical and

structural factors. These include: the nation's role in the international division of

labor, the stage of the nation's economic development, the political organization of

decision-making, and the role of language in broader social policy (Tollefson

1986).

Critique of the Neoclassical Model

T h e neoclassical model of language planning dominates research in the field.

This approach has conceptualized language planning as similar to other forms of

planning and has demonstrated that, like other resources, language can be planned

(Rubin and Jernudd 1971). This achievement has resulted, however, in the

separation of language planning from historical and structural processes that might

explain the causes and consequences of particular policies. T h e issue is not the

assumption that planners behave rationally or that the attempt to maximize

benefits is an essential characteristic of the planning process. T h e problems with

the neoclassical approach involve (1) the nonhistorical nature of the approach and

the resulting lack of attention to structural constraints on decision-making; and (2)

limitations in the model's ability to provide a theoretically sound evaluation of

plans and policies.

The assumption that planners formulate plans and policies in response to their

rational analysis of the language situation constitutes a separation of the planning

process from history. This "freezing" of history precludes analysis of the historical

causes for adoption of the planning approach or for specific decisions. M o r e o v e r ,

the assumption that planners base their decisions upon rational cost-benefit

analysis ignores the issue of why particular groups may benefit more than others

from a particular policy. Critics of the neoclassical approach point out that costs

and benefits are not distributed equally throughout a population and that costs and

benefits are determined by existing political and economic structures, of which

language planning bodies arc only a small part.

T h e neoclassical definition of successful planning is attainment of formulated

goals (Rubin 1971). This definition limits evaluation to a comparison of formulated

goals and implemented plans, and precludes evaluation that is "external" to the

planning process (Tollefson 1981a). This limited view of evaluation has profound

political implications. If planning bodies reflect the interests of dominant groups

(and this is one of the main claims of the historical-structural approach), then the

neoclassical approach provides the theoretical basis for preserving those interests.

That is, the neoclassical model provides no basis for a social scientific critique of

the effects of plans and policies on language rights, language use, or the distribu-

tion of wealth and power. That the neoclassical model is nonhistorical and amoral

in its evaluation of plans and policies can be seen in the G e r m a n n policy of

restricting use of Slavic languages in certain areas of Southern Austria during the

Second World War. Within the neoclassical approach, that policy is considered to

be "successful" if it is effectively implemented, even by means of violence and

other forms of coercion.

T h e failure of the neoclassical model to a c c o m m o d a t e coercion reflects its

assumption that language choice is predictible but " f r e e . " T h a t is, within the

neoclassical model, a population affected by policies analyzes costs and benefits

and then makes a free choice on that basis. When the model is applied to language

learning, it compares the costs of learning (e. g., time, money) and the benefits (e.

g., better jobs, educational opportunities), and assumes that learning will take

place when the benefits significantly outweigh the costs. This analysis fails to

recognize that there may be no real alternative. To attribute the use of G e r m a n by

Slavic people in Southern Austria in the 1940s to their cost-benefit analysis utterly

fails to capture the historical context for this important language shift. Within the

neoclassical approach, there is no theoretical difference between the acquisition of

G e r m a n among Slavs in Austria during the 1940s and the acquisition of French by

a highly motivated group of American high school students on vacation in Paris.

Critique of the Historical-Structural Model

Although the neoclassical model explains planning decisions with reference to

cost-benefit analysis, others argue that planning decisions are in fact manifestations

of the historical and structural factors that d e t e r m i n e the alternatives available as

well as their relative costs and benefits. The historical-structural model assumes

that planning is rational, but emphasizes instead the macrostructural forces affec-

ting planning. Individual actions are explained by locating individuals within the

larger political-economic system, primarily with reference to class, the central unit

of analysis, but also with reference to religion, ethnicity, and other such variables.

Within the historical-structural model, the costs and benefits of learning a language

(or not learning one) are the result of historical and structural variables which the

neoclassical model holds constant, and thus ignores.

The primary difficulty with the historical-structural approach is that there is no

necessary connection between structural categories (e. g., class) and the actions of

specific planners or groups. Individuals may hold varying positions and m a k e

varying decisions that cannot be directly explained in historical-structural terms.

Related problems are the resiliency of policies that may persist long after planners

have concluded that they are not in their best interests, and the capacity of politico-

administrative systems to alter or subvert plans as they are implemented (Tollefson

1981b). In such cases, the model's emphasis on historical and structural factors

makes it difficult to explain individual decision-making. At times, the approach

seems to view individuals strictly as victims or beneficiaries of historical and

structural factors. A b u - L u g h o d (1975:201) summarizes this view as follows: " H u -

man beings, like iron filings [are] impelled by forces beyond their conscious control

and, like atoms stripped of their cultural and temporal diversity, [are] denied

creative capacity to innovate and shape the worlds f r o m which and into which they

are m o v e d . "

In contrast to the severe restriction on evaluation implicit in the neoclassical

a p p r o a c h , the historical-structural approach presumes that plans which are success-

fully implemented will serve dominant interests, and thus the neoclassical evalu-

ation of plans is relatively u n i m p o r t a n t . Of far greater importance is evaluation of

the effects of policies upon historical-structural factors, most significantly on the

distribution of economic resources and political power. Concern for language

rights is an associated issue in that the exercise of language rights reflects the

different economic status of language communities; m o r e o v e r , language rights may

be the focus for conflict between competing groups.

Part II - Issues of Ideology and Social Organization

Although the neoclassical and historical-structural approaches coexist within

the field (at times, within a single analysis), language planning research has been

dominated by the neoclassical approach. T h e preoccupation with individual deci-

sion-making has led to repetitive typologies of language planning processes and

settings, and to individual case studies having little theoretical value. In large part,

these limitations are due to the underlying ideology of the neoclassical approach

and its narrow view of the p r o p e r content of social research.

O n e effect of the dominance of the neoclassical model is an emphasis on the

characteristics of individuals and groups affected by planning decisions. In studying

second language acquisition, for instance, researchers list characteristics of lear-

ners, such as motivation, in order to formulate hypotheses about rate of learning

and eventual level of attainment. Yet the mechanisms linking these characteristics

to language acquisition are not specified. For instance, studies in C a n a d a examine

the effectiveness of planned attempts to increase learners' motivation (see Pool

1974). Similarly, in special programs for refugees and immigrants, the U . S.

D e p a r t m e n t of State emphasizes the values and attitudes of individual learners as

the key to successful language learning, health, and employment (Tollefson 1989).

In such cases, the neoclassical model locates the primary variables within the

individual. T h e model thus shares assumptions with a broad range of social science

research focused on individual decision-making, such as the equilibrium model of

economics that is expressed most explicitly in supply-side theory (Bach and

Schraml 1982). These assumptions express the underlying belief that the key to

understanding social systems is the individual, that differences between socio-

political systems express the cumulative effect of individual decisions, and that the

p r o p e r focus of social science is the analysis of those decisions.

These premises are articles of faith. That is, they constitute an ideology that is

not subject to empirical verification. Yet they profoundly affect the relationship

between researchers and the object of their study. First, these premises insulate

planners f r o m any evaluation which is external to the planning process. T h e only

evaluative criterion is whether stated goals are achieved. Within the neoclassical

model, the researcher is an objective observer who is not part of the historical-

structural context. T h e researcher's primary challenge is to analyze the planning

process without "interfering" in it. As a result, the field generally does not

encompass research on a p p r o p r i a t e social, political, and economic criteria for

evaluating policies. O n e result is that researchers have little impact on policy

making. Indeed, neoclassical ideology presents a theoretical obstacle to resear-

chers' involvement in the planning process.

T h e premises of the neoclassical model have also limited the ability of resear-

chers to respond to the disillusionment with social planning that has characterized

the social sciences since the early 1970s. Neoclassical advocates of the planning

approach can argue merely that better policies d e p e n d on more accurate informa-

tion. T h e y d o not examine the forces that lead to adoption or rejection of the

planning a p p r o a c h , the historical and structural factors which establish evaluative

criteria, or the political and economic interests that benefit from the perceived

failure of planning.

T h e neoclassical approach is particularly unsuited to deal with two additional

issues. First, how do language communities form and how d o they come to invest

their language(s) with varying degrees of value? Neoclassical theory is limited to

deriving typologies of language communities based on their linguistic characteri-

stics, their functional variation, and their degree of multilingualism. It is unable to

develop a theory to account for the formation and development of language groups

and the range of linguistic variation within t h e m . Moreover, it is unable to explain

why some communities are willing, for instance, to go to war over language issues,

while others easily accept language loss, and still others exhibit a flexible attach-

ment to language patterned by factors that are outside the neoclassical model.

The neoclassical model also cannot handle a second set of issues: What are the

mechanisms by which changes take place in language structure and language use,

and how does the language planning process affect these mechanisms? T h e

neoclassical approach is limited to correlating planning decisions and language

changes; it is unable to specify the mechanisms by which planning brings about

these changes. T h u s it has n o predictive power.

In order to develop a theory of language planning, the field requires emphasis

on those areas the neoclassical model has ignored: a theoretical account of the

mechanisms by which planning affects the development of language communities

as well as the structure and function of their language varieties. Because the

historical-structural approach is concerned with such issues, it offers some hope

that a theory of language planning can be derived.

A central tenet of the approach is that the action of groups is fundamentally

different f r o m the sum of the individual actions of its m e m b e r s . T h u s planning

bodies as well as populations affected by their decisions are viewed as products of

history and the social relationships which organize groups. T h e primary task of the

field is to develop a theory of language planning that makes explicit the mecha-

nisms by which the planning process shapes the history and structure of language

communities. Emphasis on individual decisions by planners and policy makers

cannot fulfill this need.

A n additional difficulty with the neoclassical model is the assumption that

language is a resource like any other resource, with economic value for which costs

may be expended (Fishman 1971). This assumption is the basis for treating

language learning and language change as the result of cost-benefit analysis. Within

the historical-structural a p p r o a c h , language is unlike most other resources (though

like labor) because of the social relationships that give it form in linguistic

communities (cf. Bach and Schraml 1982; W o o d 1982). Language involves histori-

cally real people organized into communities according to roles, symbols, and

ideologies that may not correspond to the economic logic of cost-benefit analysis.

T h e possibilities for planning, therefore, depend upon the social organization of

communities. T h u s the task for research is to explain the link between the

organization of these communities, changes in their language structure and use,

and the planning process. A plan which aims to change language structure or use

may require a transformation of existing social relationships. T h u s analysis of

language planning cannot be analytically separated from historical processes of

structural transformation.

T h e historical-structural model rejects the neoclassical separation between the

researcher and the language planning process. A central task of the approach is

analysis of the historical and structural basis of social science theories. T h e

approach presumes that shifts in theoretical perspective have a historical basis and

that all theories are e m b e d d e d in sociopolitical structure. This central importance

of the underlying ideology of social theory has not been widely recognized within

the field (though see Khubchandani 1981).

Conclusion

T h e primary theoretical task currently facing the field is to specify the processes

for the formation of linguistic communities and ways in which planning can affect

those processes. At present, we can roughly outline the direction which this inquiry

is likely to take. Historical-structural factors are responsible for defining communi-

ties. Communities may develop language varieties which they perceive to be their

own without regard to linguistic "facts" ( e . g . , in the case of similar varieties

considered to be different "languages"). T h e development of those varieties

follows historical processes that govern a range of characteristics that define

communities, including religion, ethnicity, and class. Planning may affect language

change only to the extent permitted by historical-structural factors.

This sketch suggests directions for research. U n d e r what historical and structu-

ral conditions will language come to be an identifying characteristic of a commu-

nity? What historical and structural conditions permit language to lose its identify-

ing power? H o w do language communities perceive the role of planning bodies,

and what factors account for varying perceptions? U n d e r what conditions will

different linguistic groups be transformed into a unified community? What constra-

ints affect planned attempts to change language structure and language use?

These and other research questions are part of a complex effort to develop

a theory of language planning. Ultimately, a theory of planning and a theory of

language must be integrated. Language change is central to both. Until that broad

synthesis is achieved, the field of language planning would benefit from a sustained

effort to examine the historical-structural context of the planning a p p r o a c h ,

planning institutions and decision-making processes, and the causes and effects of

planning within sociopolitical communities.

References

A b u - L u g h o d , J. 1975. C o m m e n t s : T h e End of the Age of Innocence: Migration and Urbanization,

edited by B. DuToit and H. Safa. T h e Hague: M o u t o n , pp. 201-208.

A l i s j a h b a n a , S. T a k d i r . 1974. L a n g u a g e Policy, L a n g u a g e E n g i n e e r i n g and Literacy in I n d o n e -

sia and Malaysia: A d v a n c e s in L a n g u a g e Planning, edited by J o s h u a A . F i s h m a n . T h e H a g u e :

M o u t o n , pp. 391-416.

B a c h R o b e r t L . , a n d L i s a A . S c h r a m l . 1982. Migration, Crisis, and Theoretical Conflict:

I n t e r n a t i o n a l Migration Review 16, no. 2, pp. 320-341.

B a r n e s , D a y l e . 1977. National L a n g u a g e Planning in China: L a n g u a g e Planning Processes, edited

by J o a n R u b i n , Bjrn H. J e r n u d d , Jyotirindra D a s G u p t a , J o s h u a A F i s h m a n , and C h a r l e s A .

F e r g u s o n . T h e H a g u e : M o u t o n , p p . 255-274.

D a s G u p t a , J y o t i r i n d r a . 1970. L a n g u a g e Conflict and National D e v e l o p m e n t . Berkeley: Uni-

versity of California Press.

E a s t m a n , C a r o l M. 1983. L a n g u a g e Planning: A n I n t r o d u c t i o n . San Francisco: C h a n d l e r and

Sharp.

F i s h m a n , J o s h u a A . 1971. T h e Sociology of L a n g u a g e : An Interdisciplinary Social Science

A p p r o a c h to L a n g u a g e in Society: A d v a n c e s in the Sociology of L a n g u a g e , V o l u m e I, edited by

J o s h u a A . F i s h m a n . T h e H a g u e : M o u t o n , pp. 217-404.

1974. A d v a n c e s in L a n g u a g e Planning: International Perspectives. T h e H a g u e : M o u t o n .

F i s h m a n , J o s h u a A., J y o t i r i n d r a D a s G u p t a , B j r n H. J e r n u d d , a n d J o a n R u -

b i n . 1971. Research O u t l i n e for C o m p a r a t i v e Studies of L a n g u a g e Planning. In R u b i n and

J e r n u d d , p p . 293-306.

H o e v a r , T o u s s a i n t . 1982. E c o n o m i c Costs of Linguistically Alternative C o m m u n i c a t i o n s Sy-

stems: T h e C a s e of U z b e k i s t a n : Nationalities P a p e r s 10, p p . 55-64.

J e r n u d d , B j r n H . 1971. N o t e s on E c o n o m i c Analysis for Solving L a n g u a g e P r o b l e m s . In R u b i n

and J e r n u d d , pp. 263-272.

J e r n u d d , B j r n H . 1983. Evaluation of L a n g u a g e Planning: W h a t H a s the Last D e c a d e Accompli-

s h e d ? : Progress in L a n g u a g e Planning, edited by J u a n C o b a r r u b i a s and J o s h u a A. F i s h m a n .

Berlin: M o u t o n , pp. 345-378.

J e r n u d d , B j r n H . , a n d J y o t i r i n d r a D a s G u p t a . 1971. T o w a r d s a T h e o r y of L a n g u a g e

Planning. In R u b i n and J e r n u d d , pp. 195-216.

K h u b e h a n d a n i , L a c h m a n M. 1981. L a n g u a g e Planning in Plural Societies. P u n e , India: C e n t r e

for C o m m u n i c a t i o n Studies.

L e n c e k , R a d o . 1971. P r o b l e m s in Sociolinguistics in the Soviet U n i o n : G e o r g e t o w n University

M o n o g r a p h Series on L a n g u a g e s and Linguistics 24, p p . 269-301.

M a c k e y , W i l l i a m F . , a n d A l b e r t V e r d o o d t . 1975. T h e Multinational Society: P a p e r s of the

Ljubljana Seminar. Rowley, Massachusetts: N e w b u r y H o u s e .

P o o l , J o n a t h a n . 1972. National Diversity and L a n g u a g e Diversity: A d v a n c e s in the Sociology of

L a n g u a g e , V o l u m e II, edited by J o s h u a A . Fishman. T h e H a g u e : M o u t o n , p p . 213-230.

1974. Mass Opinion on L a n g u a g e Policy: T h e Case of C a n a d a : A d v a n c e s in L a n g u a g e Planning,

edited by Joshua A . F i s h m a n . T h e H a g u e : M o u t o n , pp. 481-492.

R u b i n , J o a n . 1971. E v a l u a t i o n and L a n g u a g e Planning. In R u b i n and J e r n u d d , pp. 217-252.

R u b i n , J o a n a n d B j r n H. J e r n u d d . 1979. C a n L a n g u a g e Be P l a n n e d ? H o n o l u l u : University

Press of Hawaii.

S h a w , P. 1975. Migration T h e o r y and Fact. Philadelphia: Regional Science R e s e a r c h Institute.

T h o r b u r n , T h o m a s . 1971. Cost-Benefit Analysis in L a n g u a g e Planning. In R u b i n and J e r n u d d ,

pp. 253-262.

T o l l e f s o n , J a m e s W . 198 l a . Alternative P a r a d i g m s in the Sociology of L a n g u a g e : W o r d 32, no. 1,

p p . 1-14.

1981b. Centralized and Decentralized L a n g u a g e Planning: L a n g u a g e P r o b l e m s and L a n g u a g e

Planning 5, no. 2, pp. 175-188.

1986. L a n g u a g e Policy and the Radical Left in the Philippines: T h e N e w P e o p l e ' s A r m y and Its

A n t e c e d e n t s : L a n g u a g e P r o b l e m s and L a n g u a g e Planning 10, no. 2, pp. 177-189.

1989. Alien Winds: T h e R e e d u c a t i o n of A m e r i c a ' s Indochinese R e f u g e e s . New Y o r k : P r a e g e r .

W o o d , C h a r l e s H . 1982. Equilibrium and Historical-Structural Perspectives on Migration: Inter-

national Migration Review 16, no. 2, pp. 298-319.

POVZETEK

R a z i s k o v a n j e jezikovnega n a r t o v a n j a zahteva premiljene n a p o r e za o b l i k o v a n j e jezikovnega

ustroja in jezikovne r a b e . O d 60. let je p o d r o j e jezikovnega n a r t o v a n j a hitro raslo, ni pa se razvila

s t r n j e n a teorija jezikovnega n a r t o v a n j a . T o je d e l o m a posledica dveh t e k m u j o i h analitinih pristopov

na tem p o d r o j u : novoklasinega in z g o d o v i n s k o s t r u k t u r a l n e g a . Prvi d o m n e v a , da so odloitve o jeziku

rezultat individualnih analiz strokov in koristi. R a z i s k o v a n j e z n o t r a j novoklasinega pristopa poskua

opisati in razloiti to p o d l a g o za individualna jezikovna o d l o a n j a . V t e m pristopu se jezikovna politika

o c e n j u j e s a m o glede na s t o p n j o u j e m a n j a med izraenimi narti in doseenimi cilji. Z g o d o v i n s k o s t r u k t u -

ralni pristop pa n a s p r o t n o p o u d a r j a omejitve pri o d l o a n j u , r a z m e r j e m e d jezikom in drugimi podroji

d r u b e n e g a n a r t o v a n j a odloitve o jeziku. T a prispevek protistavlja novoklasini in zgodovinskostruk-

turalni pristop glede na e n o t o analize, ki j o e d e n ali d r u g u p o r a b l j a , vlogo zgodovinskega raziskovanja

in n a m e n v r e d n o t e n j a .

Novoklasini in zgodovinskostrukturalni pristop t o r e j o d r a a t a osnovne razlike, vpletajo ideoloke

usmeritve predlagalcev o b e h pristopov, pa tudi razline poglede na vlogo individualne izbire in

skupinskega v e d e n j a pri raziskovanju d r u b e n e znanosti. T e razlike se raziskujejo s p o s e b n i m ozirom na

njihov vpliv na teorijo jezikovnega n a r t o v a n j a .

Na k o n c u se p r e d l a g a j o b o d o e smeri za teoretino raziskovanje n a r t o v a n j a jezikov. P o s e b e n

p o u d a r e k je d a n p o t r e b i po strnjeni teoriji jezika in jezikovnega n a r t o v a n j a .

You might also like

- Principles of Academic WritingDocument1 pagePrinciples of Academic WritingYamith José FandiñoNo ratings yet

- Well Written PaperDocument24 pagesWell Written PaperDavid ClarkNo ratings yet

- Academic Writing PDFDocument20 pagesAcademic Writing PDFYamith José FandiñoNo ratings yet

- Essential Elements Academic WritingDocument1 pageEssential Elements Academic WritingYamith José FandiñoNo ratings yet

- Academic EssayDocument2 pagesAcademic EssayMariya MulrooneyNo ratings yet

- Brief - Guides - Elements of An Essay PDFDocument3 pagesBrief - Guides - Elements of An Essay PDFYamith José FandiñoNo ratings yet

- Signal Words and PhrasesDocument2 pagesSignal Words and PhrasesSanjeeb KafleNo ratings yet

- Genres and Academic WritingDocument3 pagesGenres and Academic WritingYamith José FandiñoNo ratings yet

- Academic Writing Principles and PracticeDocument1 pageAcademic Writing Principles and PracticeYamith José FandiñoNo ratings yet

- Academic Writing Expressing Opinion and AttitudeDocument5 pagesAcademic Writing Expressing Opinion and AttitudeYamith José FandiñoNo ratings yet

- The Writing ProcessDocument43 pagesThe Writing Processmanuelgilbert76100% (2)

- Useful PhrasesDocument8 pagesUseful PhraseswinnieXDNo ratings yet

- Academic Writing LiteratureDocument9 pagesAcademic Writing LiteratureBerna GündüzNo ratings yet

- Six FeaturesDocument2 pagesSix FeaturesanitamarquesNo ratings yet

- Language Teaching ResearchDocument23 pagesLanguage Teaching ResearchMickey Ambareen100% (1)

- CALLA Learning Strategies-How To Teach ThemDocument5 pagesCALLA Learning Strategies-How To Teach ThemYamith José FandiñoNo ratings yet

- Academic Essay StructuresDocument2 pagesAcademic Essay StructuressershxNo ratings yet

- What Is An Academic PaperDocument9 pagesWhat Is An Academic PaperDavid ClarkNo ratings yet

- Te Kawa A Maui Academic Writing Guide PDFDocument66 pagesTe Kawa A Maui Academic Writing Guide PDFYamith José FandiñoNo ratings yet

- Teacher Cognitition in Language Teaching PDFDocument29 pagesTeacher Cognitition in Language Teaching PDFYamith José FandiñoNo ratings yet

- The CALLA Model Strategies For ELL Student Success PDFDocument41 pagesThe CALLA Model Strategies For ELL Student Success PDFYamith José FandiñoNo ratings yet

- Content and Language Integrated Learning From Practice To Principles PDFDocument23 pagesContent and Language Integrated Learning From Practice To Principles PDFYamith José FandiñoNo ratings yet

- Distance Education For Teacher Training by Mary Burns EDC PDFDocument338 pagesDistance Education For Teacher Training by Mary Burns EDC PDFYamith José FandiñoNo ratings yet

- Clil Book EngDocument51 pagesClil Book EngTheencyclopedia100% (1)

- Learning Subject Matter Through The Medium of A Foreign Language ClilDocument1 pageLearning Subject Matter Through The Medium of A Foreign Language ClilYamith José FandiñoNo ratings yet

- Content Based L2 teaching-CLIL PDFDocument34 pagesContent Based L2 teaching-CLIL PDFYamith José FandiñoNo ratings yet

- Clil in PrimaryDocument2 pagesClil in PrimaryYamith José FandiñoNo ratings yet

- CLIL and The Teaching of Foreign LanguagesDocument5 pagesCLIL and The Teaching of Foreign LanguagesYamith José FandiñoNo ratings yet

- Reviews of Journal ArticlesDocument2 pagesReviews of Journal ArticlesPiyush MalviyaNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Case-Smiths Occupational Therapy For Children and Adolescents - Ebook (Jane Clifford OBrien Heather Kuhaneck)Document1,597 pagesCase-Smiths Occupational Therapy For Children and Adolescents - Ebook (Jane Clifford OBrien Heather Kuhaneck)Anthony stark100% (9)

- Lesson Plan-Water CycleDocument2 pagesLesson Plan-Water Cycleapi-392887301No ratings yet

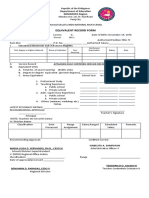

- Equivalent Record Form: Department of Education MIMAROPA RegionDocument1 pageEquivalent Record Form: Department of Education MIMAROPA RegionEnerita AllegoNo ratings yet

- Government Information Systems Plan of The PhilippinesDocument116 pagesGovernment Information Systems Plan of The PhilippinesJack Nicole Tabirao75% (4)

- 04chapter3 PDFDocument38 pages04chapter3 PDFMegz OkadaNo ratings yet

- What If - Let Your Imagination Flourish - Adobe Khan + CreateDocument5 pagesWhat If - Let Your Imagination Flourish - Adobe Khan + CreateMrs Curran SISNo ratings yet

- Integrated ReflectionDocument3 pagesIntegrated ReflectionJenny ClarkNo ratings yet

- PGD Aiml BrochureDocument27 pagesPGD Aiml BrochurePramod YadavNo ratings yet

- Assignment FP002 ORC Casanova GuadalupeDocument11 pagesAssignment FP002 ORC Casanova GuadalupeGuadalupe Elizabeth Casanova PérezNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 Philosophical Perspectives of The SelfDocument3 pagesLesson 1 Philosophical Perspectives of The SelfPortgas D. Ace83% (6)

- Social Case Study ReportDocument3 pagesSocial Case Study ReportHanabusa Kawaii IdouNo ratings yet

- Second Term Plarform English IIDocument19 pagesSecond Term Plarform English IIJohann VelasquezNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 12humss CDocument11 pagesChapter 1 12humss CBea Aizelle Adelantar Porras100% (1)

- NADCA 2012AnnualReportDocument15 pagesNADCA 2012AnnualReportwholenumberNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Learning (First Quarter) in Health 1 Most Learned Competencies Learning Competency CodeDocument3 pagesAssessment of Learning (First Quarter) in Health 1 Most Learned Competencies Learning Competency CodeRames Ely GJNo ratings yet

- Teaching Strategies in MTB 1Document6 pagesTeaching Strategies in MTB 1HASLY NECOLE HASLY LAREZANo ratings yet

- ETHICS - Reflection PaperDocument2 pagesETHICS - Reflection PaperErika Nell LachicaNo ratings yet

- Yaya Maimouna RizalDocument5 pagesYaya Maimouna RizalKriselle Ann CalsoNo ratings yet

- Sedimentation of Reservoir Causes and EffectsDocument33 pagesSedimentation of Reservoir Causes and Effects53 Hirole AadeshNo ratings yet

- Invent For SchoolsDocument14 pagesInvent For Schoolssandeep kumarNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae Yuliza Fuji 2014Document2 pagesCurriculum Vitae Yuliza Fuji 2014jeffierNo ratings yet

- Hospital Visit ReportDocument3 pagesHospital Visit ReportRania FarranNo ratings yet

- Online Railway PassesDocument23 pagesOnline Railway PassesSenthil KumarNo ratings yet

- Y1S1 2020-21 - TIMETABLE - Njoro Campus - BDocument3 pagesY1S1 2020-21 - TIMETABLE - Njoro Campus - BBONVIN BUKACHINo ratings yet

- Hedges: Softening Claims in Academic WritingDocument2 pagesHedges: Softening Claims in Academic WritingChristia Abdel HayNo ratings yet

- Abhyaas GE-PI: Sample Interview QuestionsDocument3 pagesAbhyaas GE-PI: Sample Interview QuestionsAbhyaas Edu Corp0% (1)

- Nairobi - Fulltime - 3rd Trimester 2022 Common Teaching Timetables - 08.09.2022Document5 pagesNairobi - Fulltime - 3rd Trimester 2022 Common Teaching Timetables - 08.09.2022Chann AngelNo ratings yet

- Meaning and Definition of Educational Technology PDFDocument34 pagesMeaning and Definition of Educational Technology PDFJason BautistaNo ratings yet

- Sample AcknowledgmentDocument4 pagesSample AcknowledgmentNishant GroverNo ratings yet

- Science Olympiad FlyerDocument2 pagesScience Olympiad FlyerIra RozenNo ratings yet