Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Abstinen Dalam Penjara Dan Kepuasan Sexual PDF

Uploaded by

Titah RahayuOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Abstinen Dalam Penjara Dan Kepuasan Sexual PDF

Uploaded by

Titah RahayuCopyright:

Available Formats

563271

research-article2014

TPJXXX10.1177/0032885514563271The Prison JournalCarcedo et al.

Article

The Prison Journal

2015, Vol. 95(1) 4365

The Relationship 2014 SAGE Publications

Reprints and permissions:

Between Sexual sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0032885514563271

Satisfaction and tpj.sagepub.com

Psychological Health

of Prison Inmates: The

Moderating Effects of

Sexual Abstinence and

Gender

Rodrigo J. Carcedo1, Daniel Perlman2,

Flix Lpez1, M. Begoa Orgaz1,

and Noelia Fernndez-Rouco1,3

Abstract

Research has found a relationship between sexual satisfaction and

psychological health in prisoners, although few studies have focused on

possible moderators of this relationship. The main foci of this study of

a sample of prison inmates were as follows: (a) the association between

sexual satisfaction and psychological health and (b) the moderating effects

of heterosexual activity level (abstinent vs. non-abstinent) and gender on

the relationship between these two variables. In-person interviews were

conducted with 82 males and 91 females who lived in separate modules in

Spains Topas Penitentiary. Sexual satisfaction was a significant predictor of

psychological health only for members of the sexually abstinent group. These

1University of Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain

2University of North Carolina, Greensboro, NC, USA

3University of Cantabria, Santander, Spain

Corresponding Author:

Rodrigo J. Carcedo, Department of Developmental and Educational Psychology, University of

Salamanca, Facultad de Psicologa, Avda. de la Merced, 109-131 37005 Salamanca, Spain.

Email: rcarcedo@usal.es

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UQ Library on March 13, 2015

44 The Prison Journal 95(1)

findings point to the positive effect of sexual satisfaction on psychological

health, especially for the inmates in a less favorable sexual situation (i.e.,

sexual abstinence).

Keywords

sexual abstinence, sexual satisfaction, psychological health, prison inmates

The research to be reported in this article focused on (a) the differences in

sexual satisfaction as a function of gender and the level of sexual activity

(being sexually abstinent or not), (b) the relationship between sexual satis-

faction and psychological health, and (c) the moderating effect of gender

and level of sexual activity on this relationship. Many authors have noted

that inmates suffer due to heterosexual sexual relationship deprivation in

prison (Lacombe, 1997; Levenson, 1983; Maeve, 1999; Neuman, 1982;

Snchez, 1995). However, none of the authors has empirically tested

whether these inmates showed less sexual satisfaction than the inmates

who have had sex. The role of gender in this relationship is also unknown.

In addition, some prison studies have found a relationship between sexual

satisfaction and psychological health (Carcedo, Lpez, Orgaz, Toth, &

Fernndez-Rouco, 2008), but there are no studies of whether this associa-

tion is moderated by other variables such as gender and the level of sexual

activity.

Gender, Sexual Abstinence, and Sexual Satisfaction

Female inmates have been found to show higher levels of sexual satisfaction

than males (Carcedo et al., 2008). However, after controlling for age, nation-

ality, total time in prison, actual sentence time served, and estimated time to

parole and partner status, this difference was not statistically significant

(Carcedo et al., 2011).

Several authors have reported negative feelings toward abstinence by both

male and female inmates (i.e., Lacombe, 1997; Maeve, 1999; Neuman, 1982;

Snchez, 1995). However, only one study of prison inmates has empirically

investigated the differences in the sexual satisfaction of heterosexually absti-

nent and heterosexually active inmates, finding much lower levels of sexual

satisfaction in the sexually abstinent group (Carcedo, 2005). Gender was not

taken into account in that study, although this is an important variable to con-

sider. In the present study, sexual abstinence and gender effects will be exam-

ined together with respect to inmates sexual satisfaction.

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UQ Library on March 13, 2015

Carcedo et al. 45

Sexual Satisfaction and Psychological Health

Prison inmates have been identified as an at-risk population for poor psycho-

logical health because of the distress associated with incarceration (Toch,

1977; Zamble & Porporino, 1988). One of the possible causes of this risk is

that inmates encounter difficulties in having a satisfactory sex life (Carcedo,

2005; Lacombe, 1997; Levenson, 1983; Maeve, 1999; Neuman, 1982).

Linville (1981) found that approximately three quarters of a sample of 100

males in a minimum-security prison reported emotional problems because of

sexual deprivation. In addition, sexual satisfaction and psychological health

and other well-being-related measures have been shown to be significantly

related in prison settings (Carcedo, 2005; Carcedo et al., 2008; Carcedo,

Perlman, Lpez, & Orgaz, 2012) and non-prison studies (Fegg et al., 2003;

Lau, Wang, Cheng, & Yang, 2005; Nicolosi, Moreira, Villa, & Glasser, 2004;

Taleporos & McCabe, 2002). Higher levels of sexual satisfaction were asso-

ciated with higher levels of psychological health and other well-being related

measures.

Moderating Effect of Gender and Sexual

Abstinence on the Relationship Between Sexual

Satisfaction and Psychological Health

The suffering and the deterioration of psychological health due to the lack

of sexual satisfaction have been suggested regarding male inmates

(Lacombe, 1997; Levenson, 1983; Linville, 1981; Neuman, 1982), female

inmates (Pardue, Arrigo, & Murphy, 2011; Snchez, 1995), and both gen-

ders (Carcedo et al., 2008; Carcedo et al., 2012). However, it is unknown if

the relationship between sexual satisfaction and psychological health is dif-

ferent for male and female inmates. In a study of 118 male and 70 female

prison inmates, Carcedo et al. (2008) found that sexual satisfaction signifi-

cantly explained the psychological health for both genders, although 6.2%

more of the variance was explained for females than males. Notwithstanding,

the possible moderator effect of gender was not tested. In non-prison popu-

lation studies that have strictly measured sexual satisfaction or sexual well-

being, this variable has been associated with psychological health and

happiness in both genders, but the relationship between sexual variables

and psychological measures has been slightly stronger among women than

among men (Laumann et al., 2006; Taleporos & McCabe, 2002). Thus, the

possibility that gender moderates the relationship between sexual satisfac-

tion and psychological health warrants consideration. This will also be

examined in the present study.

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UQ Library on March 13, 2015

46 The Prison Journal 95(1)

In arguing that a lack of sexual satisfaction can negatively impact prison

inmates psychological health, most authors (Lacombe, 1997; Levenson,

1983; Maeve, 1999; Neuman, 1982; Snchez, 1995) were referring mainly to

inmates who have not had heterosexual sexual relationships during their

incarceration. Thus, these authors were implicitly confounding sexual satis-

faction with sexual abstinence. Whereas sexual satisfaction reflects an evalu-

ation of ones current sexual life, sexual abstinence refers to the complete

lack of sexual relationships during a period of time. These different concepts

may delineate different situations: An inmate may have been sexually absti-

nent during the last 6 months, yet show reasonable high sexual satisfaction.

By contrast, an inmate may have been sexually active, yet have low sexual

satisfaction. In addition, the relationship between inmates sexual satisfaction

and psychological health may be different for sexual abstainers versus sexu-

ally active individuals. No prison study has investigated this moderating

effect. Notwithstanding, non-prison studies have found a stronger relation-

ship between sexual satisfaction and general well-being for those who have

been sexually deprived due to the presence of sexual dysfunctions (Lau et al.,

2005; Ventegodt, 1998), physical disabilities (Taleporos & McCabe, 2002),

amputations (Walters & Williamson, 1998), and having had germ-cell tumor

therapy (Fegg et al., 2003). Therefore, the moderating effect of being sexu-

ally abstinent versus active in the relationship between sexual satisfaction

and psychological health will be tested in this research.

According to reactance theory (RT; Brehm, 1966), any form of depriva-

tion may increase the desire for the deprived object (Brehm & Brehm, 1981),

amplifying its relevance for individuals psychological health. The major

premise of RT is that individuals wish to operate with a freedom to choose

behaviors to satisfy their needsin this case sexual needs. If their freedom is

reduced, threatened, or eliminated, individuals will become motivationally

aroused to regain this freedom (Brehm, 1966, p. 2). Thus, psychological

reactance is a motivational state directed toward the re-establishment of free

behaviors that have been eliminated or threatened with elimination. (p. 9).

With reference to this research, reactance is likely to be high among inmates

whose access to heterosexual activity is thwarted by their circumstances. We

believe that in enhancing the value of sex, such reactance may intensify the

association between their sexual satisfaction and psychological well-being.

Control Variables

Other variables have been demonstrated to be related to inmates psychologi-

cal health. For example, a set of socio-demographic and punishment-related

variables have been found to be important. Poorer mental health has been

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UQ Library on March 13, 2015

Carcedo et al. 47

exhibited by inmates who are younger, Caucasian (Lindquist, 2000), married

(Lindquist, 2000; Lindquist & Lindquist, 1997), and who have longer sen-

tences and a longer expected time prior to their release (James & Glaze,

2006). Due to these findings, the authors include age, ethnic group-nationality,

partner status, total time in prison, actual sentence time served, and estimated

time to parole as control variables when predicting psychological health.

Although the relationship between these variables and sexual satisfaction has

not been investigated in prison research, these variables were also included in

analyzing the effect of sexual abstinence on sexual satisfaction because of

their potential association with inmates sexual satisfaction.

In addition, masturbation has been found to be related to sexual satisfac-

tion and well-being-related measures in non-prison studies (Das, 2007; Das,

Parish, & Laumann, 2009; Langstrom & Hanson, 2006), and social loneli-

ness has been shown to be an important predictor of prisoners psychological

health (Carcedo et al., 2008). Taking these results into consideration, we also

included the frequency of masturbation as a possible predictor of sexual sat-

isfaction and psychological health, and social loneliness as a possible predic-

tor of psychological health.

In sum, we set out to examine the following research questions in this

study: (a) Will gender and sexual abstinence be associated with inmates

sexual satisfaction after controlling for age, ethnic group-nationality, part-

ner status, total time in prison, actual sentence time served, estimated time

to parole, and frequency of masturbation? (b) Will sexual satisfaction be

associated with inmates psychological health after controlling for age, eth-

nic group-nationality, partner status, total time in prison, actual sentence

time served, estimated time to parole, social loneliness, and frequency of

masturbation? (c) Will gender and/or sexual abstinence play a moderating

role in the relationship between sexual satisfaction and psychological

health? More specifically, will sexual satisfaction explain more variance in

the psychological health among inmates in the worse-off heterosexually

abstinent group than among inmates in the heterosexually active group?

Will sexual satisfaction explain more variance in the psychological health

of females than of males?

Method

Design

The data for this study were collected in two sessions. The primary variables

of our study were all evaluated in the first session. These included sexual

satisfaction (the main predictor variable), social loneliness and frequency of

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UQ Library on March 13, 2015

48 The Prison Journal 95(1)

masturbation (other relevant interpersonal and sexual predictors), the moder-

ating variables (heterosexual activity level and gender), and the control vari-

ables (age, nationality, partner status, total time in prison, actual sentence

time served, and anticipated time to parole). The outcome variable (psycho-

logical health) was evaluated in the second session. Depending on the

inmates schedules, the second session was conducted approximately a week

later. The heterosexual activity status of participants (i.e., abstinent vs. het-

erosexually active) was obtained in both sessions. It was checked in the sec-

ond session to verify that the situation of the inmates had not changed between

sessions. There was no participant change.

Participants

In total, 173 medium-security prison inmates (91 men and 82 women) from a

prison in the northwestern region of Spain provided data for this study during

2008. Their average age was 35.10 years, with a range from 20 to 62.

Regarding nationality, 41.04% (n = 71) were Spanish, whereas 58.96% were

foreigners (n = 102). While 35.26% (n = 61) had no romantic partner, 64.74%

(n = 112) had a partner. The mean of total time in prison for all offenses,

actual sentence time served for their current offense, and estimated time to

parole were 51.35, 42.61, and 24.98 months, respectively.

With respect to the characteristics of the sample regarding sexual behav-

ior, 46.24% (n = 80; 53 men and 27 women) of the inmates had been sexually

abstinent for at least 6 months, and 53.76% (n = 93; 29 men and 64 women)

had had sexual relationships in the last 6 months. Inmates reported that all

their sexual relationships had been heterosexual and had included vaginal

coitus at least once in the last 6 months. All these sexual behaviors were con-

sensual except for the case of one female and one male inmate who had also

had consensual sexual relationships. Finally, of the heterosexually active

group, 6.59% reported having maintained sexual relationships during their

furloughs outside the prison, 74.72% reported having had sexual relation-

ships in the conjugal visits rooms inside the prison, and 24.18% reported

having had sexual relationships in other areas inside the prison where men

and women share different activities (e.g., at their workplace in prison, the

socio-cultural module, the gym, etc.). Although some of the inmates reported

having had homosexual contacts in prison, none reported having had homo-

sexual contacts during the 6 months prior to data collection.

Participants were selected to have an equal number of men and women.

After stratifying by gender, 80% of the participants were randomly selected,

while 20% were selected under a snowball sampling scheme (Goodman,

1961). Participants were excluded under the following conditions: (a) they

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UQ Library on March 13, 2015

Carcedo et al. 49

had been in prison for less than 6 months, the time considered necessary to

adapt to prison life and develop new relationships inside the facility; (b) the

estimated time to parole was less than a month, a period when inmates are

usually focused on being released more than their life in prison; (c) they did

not speak Spanish or English; (d) they had been diagnosed with a serious

mental disorder (e.g., psychotic and mood disorders); or (e) they were not in

optimal condition to be interviewed (e.g., under the influence of drugs or

expressing high levels of anxiety or distrust toward the interviewer). Only

eight potential participants declined or stated that they were not interested in

being interviewed. Due to an interviewer error or that the inmate refused to

answer, 23 participants skipped a single item from one or more scales, but

they were included in the analyses using the mean of the other items in the

scale that had been answered. All of the participants considered the interview

as a generally positive experience, especially because it gave them an oppor-

tunity to express their personal worries and feelings.

Procedure

This study is part of a larger project that involved two interview sessions. The

first author conducted in-person interviews with each participant in a private

room, separated from the rest of the inmates, in the inmates module. Both

sessions consisted of interview questions formulated specifically for this

project and standardized questionnaires. Both kinds of measures were mixed

in the two sessions. The time needed to complete questionnaires was kept

short (approximately 30 min) to avoid participants either getting tired or

experiencing an invasive sense of being questioned (i.e., an interrogation

effect).

The first session lasted between 60 and 90 min. Before the start of the

interview, the interviewer spent a significant amount of time gaining each

inmates trust. Usually, the trust-building phase took around 20 min.

However, depending on the inmates responsiveness, in some cases it took

up to 2 hr. Before beginning the interview itself, participants were invited

to read and sign the consent form. They also were asked to participate and

were informed about the possibility of leaving the study whenever they

wished to do so. In addition, participants were informed about the confiden-

tiality and anonymity of their answers, which meant that any information

given during the interview would not be divulged and their names would

not appear in any printed reports. No names were attached to the interviews

and an informed consent statement was signed by the inmate and the inter-

viewer. Approximately a week later, the second session was conducted; it

usually lasted around 30 min.

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UQ Library on March 13, 2015

50 The Prison Journal 95(1)

Measures

Primary predictor variable: Sexual satisfaction. To measure this construct, the

Sexual Satisfaction subscale of the Multidimensional Sexual Self-Concept

Questionnaire (MSSCQ; Snell, 1995) was used. A total of five items were

scored on 5-point Likert-type scales that ranged from 1 (not at all character-

istic of me) to 5 (very characteristic of me). The total sexual satisfaction score

was obtained by summing the scored items and dividing them by the number

of items answered. Possible scores range from 1 to 5 (high sexual satisfac-

tion). Coefficient alpha for this subscale was .96.

Other interpersonal and sexual predictor variables: Social loneliness and frequency

of masturbation. To measure loneliness, the five-item social loneliness sub-

scale of the short version of the Social and Emotional Loneliness Scale for

Adults (SELSA-S; DiTommaso, Brannen, & Best, 2004) was used. Items

were answered on a 7-point Likert-type scale that ranged from 1 (strongly

disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The total score was obtained by adding the

individual scores and dividing them by the number of items answered. Pos-

sible scores range from 1 to 7 (high loneliness). Coefficient alpha for this

subscale was .81.

The following question was used to measure masturbation: Masturbation

is a normal and very common human behavior. In the last 6 months, how

often did you masturbate? The possible answers ranged from 1 (never), 2

(less than once per month), 3 (once or twice per month), 4 (once or twice per

week), 5 (once per day), to 6 (more than once per day).

Moderating variables: Heterosexual activity level (abstinence) and gender.Absti-

nence was recorded as 0 for the inmates who had not experienced any sexual

relationships in the past 6 months, and 1 for the inmates who had had at least

one sexual relationship in the last 6 months. Gender was recorded as 0 for

females and 1 for males.

Outcome variable: Psychological health. To assess this dimension, the short,

Spanish version of the Psychological Health subscale of the World Health

Quality of Life scale (WHOQOL-BREF; Lucas, 1998) was used. Six

items were scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale that ranged, with differ-

ent labels, from 1 (not at all; very dissatisfied; never) to 5 (extremely-completely;

very satisfied; always). The Psychological Health State score was obtained

by summing the individual scores and dividing them by the number of

items answered. Possible score range from 1 to 5 (positive health). Alpha

was .72.

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UQ Library on March 13, 2015

Carcedo et al. 51

Control variables

Age. Inmates were asked to state their ages, and this variable was con-

firmed using inmate penitentiary records to ensure accuracy.

Partner status. This item was rated as 0 for inmates without a partner and

1 for inmates in a romantic relationship.

Nationality. Nationality was split into Spaniards (0) versus foreigners (1).

Total time in prison. This variable was obtained from the sum of all time

spent in a prison for previous and current offenses. It was collected by review-

ing inmates penitentiary records and recorded in months.

Actual sentence time served.This item denotes the time spent in prison

since the last entry (i.e., during the current prison term). It also was obtained

from inmate penitentiary records and listed in months.

Estimated time to parole.After discussions with the legal advisors from

Topas Penitentiary, we chose to take three quarters of participants actual

sentences as the expected time when inmates would be paroled due to the

fact that it was the modal parole time. This fact was familiar to the inmates,

thus they were likely to expect parole around this time. Clearly, actual time to

parole varies, depending on inmates characteristics and behavior. The esti-

mated time to parole was the amount of time remaining before each inmates

expected parole date. This variable was also recorded in months.

Analysis Strategy

The primary research issue addressed by this project is how the sexual satis-

faction of heterosexually abstinent (male and female) and heterosexually

active (male and female) inmates is related to their psychological health.

Because of the presence of non-orthogonality in the design (i.e., sexual activ-

ity level is significantly associated with gender, see Table 1), the individual

and combined effects of sexual activity level, gender, and sexual satisfaction

on psychological health were assessed. In particular, we used the model com-

parisons strategy recommended by Neter, Kutner, Nachtsheim, and

Wasserman (1996) who applied previous authors recommendations on

ANOVA designs (Appelbaum & Cramer, 1974; Cramer & Appelbaum, 1980;

Maxwell & Delaney, 1990) to regression designs. Following Neter et al.s

recommendations, a logical sequence of model comparisons is undertaken,

beginning with the test of the higher order interaction (third order: Sexual

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UQ Library on March 13, 2015

52 The Prison Journal 95(1)

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of Major Variables for Sexual-Abstinent and Non-

Sexual-Abstinent Groups.

Sexually abstinent Sexually active

(n = 80) (n = 93)

M (SD) M (SD)

Variables % % p

1. Age 35.44 (8.37) 34.81 (7.18)

2. Nationality (Spanish) 39.44% 60.56%

3. Partner status (with partner) 24.11% 75.89% ***

4. Total time in prison 58.78 (57.08) 44.96 (33.06)

5. Actual sentence served 44.06 (47.25) 41.35 (32.05)

6. Time to parole 25.68 (21.51) 24.37 (16.24)

7. Social loneliness 3.84 (1.80) 3.03 (1.60) **

8. Frequency of masturbation 2.86 (1.42) 2.69 (1.40)

9. Gender (males) 64.63% 35.37% ***

10. Sexual satisfaction 1.44 (0.78) 3.38 (1.34) ***

11. Psychological health 3.32 (0.78) 3.65 (0.67) **

Note. Chi-squares were performed using the exact test. Asymptotic likelihood ratio chi-

squares yielded the same significant differences.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

satisfaction Sexual activity level Gender), proceeding to a test of lower

order interactions (second order: Sexual satisfaction Sexual activity level,

Sexual satisfaction Gender, and Sexual activity level Gender) in the pres-

ence of the others (eliminating tests), and finally a test of each interaction in

the absence of the other (ignoring tests). At the end of this procedure, the

so-called conditional effects are tested. These effects are also called main

effects in ANOVA designs (see Hayes & Matthes, 2009). Akin to the proce-

dure used with second-order interactions, at this stage, a test of each main

effect in the presence of the other main effects is performed (eliminating

tests), and, finally, a test of each main effect in the absence of the other main

effects (ignoring tests) is performed. Only the minimum number of tests nec-

essary to logically determine a final statistical model is performed, allowing

valid conclusions to be drawn even in the presence of highly non-orthogonal

regression models (Neter et al., 1996).

In all the analyses reported here, participant age, partner status, national-

ity, total time in prison, actual sentence time served, estimated time to parole,

social loneliness, and frequency of masturbation were controlled because

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UQ Library on March 13, 2015

Carcedo et al. 53

previous research has linked them to prisoner and non-prison psychological

health (Carcedo et al., 2008; Das, 2007; Das et al., 2009; James & Glaze,

2006; Langstrom & Hanson, 2006; Lindquist, 2000; Lindquist & Lindquist,

1997). Also, participant age, total time in prison, actual sentence time served,

estimated time to parole, social loneliness, frequency of masturbation, and

sexual satisfaction were centered before entry into the models. Thus, the

parameter estimates associated with sexual satisfaction, gender, and sexual-

abstinent group are referenced to an average Spaniard prison inmate with-

out a partner (i.e., one of an average age of 35 years, who has served an

average 51 months of total time in prison, who has been incarcerated for an

average 42 months during the current stay, and who has an average esti-

mated 25 months remaining until parole).

As shown in Table 1, heterosexually abstinent and heterosexually active

inmates are differently distributed within gender categories. Under these cir-

cumstances, asymptotic likelihood ratio tests of categorical association are

likely to be inaccurate. Thus, all tests of categorical association were con-

ducted under a permutation-based exact test statistical modeling framework

(Mehta & Patel, 2002, pp. 9-39), yielding p values and conclusions that

remain valid under the conditions observed.

To study how sexual abstinence and gender were related to sexual satisfac-

tion, the same analytic approach was utilized. In this case, the logical

sequence of model comparisons starts with the test of interaction (Sexual

activity level Gender), proceeding to a test of each main effect in the pres-

ence of the other (eliminating tests), and finally a test of each main effect in

the absence of the other (ignoring tests).

SPSS 17.0 was used for data analysis. This program and the MODPROBE

script (Version 1.2) developed by Hayes and Matthes (2009) were used for

probing and plotting the interactions. The pick-a-point approach (Aiken &

West, 1991; Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003) was utilized. This proce-

dure selects representative values of the moderator variable (in this case, two

categories: 0 for sexual-abstinent, and 1 for non-sexual-abstinent) and

then estimates the effect of the focal predictor at those values.

Results

Descriptive statistics were calculated and are displayed in Table 1 separately

by heterosexually abstinent and heterosexually active inmates. To examine

whether there are mean differences based on sexual activity status for the

study variables, t tests for independent samples and chi-square tests (exact

test) were conducted.

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UQ Library on March 13, 2015

54 The Prison Journal 95(1)

Sexual Activity and Gender Differences on Sexual Satisfaction

An ANCOVA was performed to analyze the main and interaction effects of

sexual activity and gender on sexual satisfaction after controlling for age,

nationality, partner status, total time in prison, actual sentence time served,

and estimated time to parole. In short, neither gender nor the control variables

were significantly associated with sexual satisfaction. Nor were any signifi-

cant interaction effects between gender and level of sexual activity found for

sexual satisfaction. Sexual activity level, however, was significantly associ-

ated with sexual satisfaction (B = 1.805, SE = .228, R2 = .457, p < .001).

After accounting for the control variables, Bonferroni post hoc comparisons

were used to analyze the differences between the heterosexually abstinent

and heterosexually active groups, using estimated marginal means, also

called least-squares means. As was expected, the heterosexually abstinent

inmates (M = 1.511, SE = .148) reported much lower levels of sexual satisfac-

tion than the heterosexually active ones (M = 3.316, SE = .136).

Moderating Effect of Sexual Activity and Gender on the

Relationship Between Sexual Satisfaction and Psychological

Health

Regarding the interaction effect of Sexual satisfaction Heterosexual activity

level and Sexual satisfaction Gender on psychological health, a series of hier-

archical linear regression analyses were performed. The Type III Sums of Squares

and a simultaneous entry of the variables in different steps were utilized. We used

the analysis strategy described above (Neter et al., 1996). Socio-demographic

and penitentiary control variables (age, nationality, total time in prison, actual

sentence time served, and time to parole) were included in the first step; interper-

sonal and sexual variables (social loneliness and frequency of masturbation) were

included in the second step; conditional effects of sexual satisfaction, heterosex-

ual activity level, and gender were added in the third step; the three 2-way inter-

actions (Sexual satisfaction Heterosexual activity level, Sexual satisfaction

Gender, and Heterosexual activity level Gender) were added in the fourth step;

and the 3-way interaction (Sexual satisfaction Heterosexual activity level

Gender) was included in the fifth step. The third-order level interaction was not

significant. Then, this interaction was dropped from the final model, and we con-

tinued studying the model with the three second-order possible interactions.

Table 2 builds different sequences of hierarchical regression analyses,

once the three-way interaction was dropped. Model 1 only includes the con-

trol variables. Model 2 adds interpersonal and sexual variables. Model 3 adds

the conditional effects and interactions of the variables on which this study is

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UQ Library on March 13, 2015

Carcedo et al. 55

Table 2. Predictors of the Prison Inmates Psychological Health.

Psychological health

Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4

B SE B SE B SE B SE

Step 1: Control variables (socio-demographics and penitentiary)

Age 0.003 0.007 0.003 0.007 0.000 0.006

Nationality 0.399*** 0.116 0.440*** 0.107 0.487*** 0.103 0.422*** 0.096

Partner status 0.167 0.117 0.054 0.110 0.179 0.128

Total time in prison 0.000 0.002 0.001 0.002 0.000 0.002

Actual sentence served 0.002 0.003 0.002 0.002 0.002 0.002

Time to parole 0.009** 0.003 0.007* 0.030 0.006* 0.003 0.004 0.002

Step 2: Interpersonal and sexual variables

Social loneliness 0.170*** 0.030 0.158*** 0.029 0.150*** 0.028

Frequency of masturbation 0.023 0.037 0.007 0.039

Step 3: Conditional effects

Gender 0.040 0.204

Sexual activity level 0.499 0.267 0.468* 0.231

Sexual satisfaction 0.360*** 0.102 0.351*** 0.089

Step 4: Interaction model

Gender Sexual activity level 0.205 0.265

Gender Sexual satisfaction 0.014 0.086

Sexual satisfaction Sexual 0.261* 0.103 0.266** 0.101

activity level

R2 .126 .269 .360 .344

Note. The same interaction effect was found when selected only the participants who did not miss any item

from the scales (n = 150).

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

focused. Finally, Model 4 includes only the variables and the interaction that

proved to be significant in Model 3. In this last model, the parameters of

nationality, social loneliness, sexual satisfaction, heterosexual activity level

(in this case because it is necessary for the interaction term), and the interac-

tion between sexual satisfaction and heterosexual activity level were esti-

mated. In Model 1, only nationality and estimated time to parole showed to

be significant. In Model 2, the significant variables that entered in the model

were nationality, estimated time to parole, and social loneliness. Models 3

and 4 showed that nationality, estimated time to parole (not in Model 4),

social loneliness, sexual satisfaction, and the interaction between sexual sat-

isfaction and heterosexual activity level were significant. The contribution of

explained variance by the interaction term to the Model 4 was significant

(R2 = .027, p = .009). Being a foreign inmate, being lower in social loneliness,

having a shorter estimated time to parole, and being higher in sexual satisfac-

tion were associated with higher psychological health (see Table 2).

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UQ Library on March 13, 2015

56 The Prison Journal 95(1)

Table 3. Conditional Effects of Sexual Satisfaction at Two Sexual Activity Levels

on Psychological Health.

Psychological health

B SE t 95% CI

Sexual activity level

Sexual-abstinent (0) 0.351 0.089 3.956*** [0.176, 0.526]

Non-sexual-abstinent (1) 0.084 0.048 1.753 [0.011, 0.179]

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Psychological health

5 Sexual abstinence

4

3 Non-sexual abstinence

2

1

1 2 3 4 5

Sexual Satisfaction

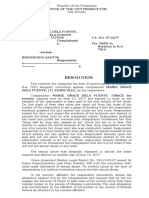

Figure 1. The moderating impact of sexual abstinence on the relationship

between sexual satisfaction and psychological health.

The level of sexual satisfaction predicted psychological health among the

sexually abstinent inmates. The more sexually satisfied inmates were, the

greater their psychological health. A similar, but non-significant trend (p =

.081) was found among the non-sexual-abstinent group (see Table 3). The

resulting interaction plot can be seen in Figure 1.

Discussion

This study found two main results: (a) Sexual satisfaction was lower for sexually

abstinent inmates in comparison to inmates who have had heterosexual sexual

relationships in the last 6 months, and (b) sexual satisfaction was a significant

predictor of psychological health but only for the sexually abstinent group.

Gender and Sexual Activity Level Differences in Sexual

Satisfaction

After accounting for the control variables, no differences in sexual satisfac-

tion scores were found between male and female inmates. This result contra-

dicts our first two studies (Carcedo, 2005; Carcedo et al., 2008) but supports

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UQ Library on March 13, 2015

Carcedo et al. 57

the findings of a more recent work (Carcedo et al., 2011) in which a set of

control variables were included. However, no control variables were included

in the other two previous studies that showed women to have a higher level

of sexual satisfaction than men (Carcedo, 2005; Carcedo et al., 2008). This

makes clear that when control variables are included, gender is no longer

significant for inmates sexual satisfaction.

In addition, the heterosexually abstinent prison inmates showed lower

sexual satisfaction than the heterosexually active group. This result is akin to

Carcedos (2005) findings. In the present study, no interaction effect of gen-

der by heterosexual activity level was found. In sum, having a sexual rela-

tionship is important for inmates psychological health, independent of the

inmate being a male or a female.

Sexual Satisfaction and Psychological Health

Independent of gender and sexual activity level, higher levels of sexual satis-

faction were associated with higher levels of psychological health. This result

is consistent with other prison studies (Carcedo, 2005; Carcedo et al., 2008;

Carcedo et al., 2012; Linville, 1981), other authors statements about prison

inmates (Lacombe, 1997; Levenson, 1983; Linville, 1981; Neuman, 1982),

and non-prison studies (Fegg et al., 2003; Lau et al., 2005; Nicolosi et al.,

2004; Taleporos & McCabe, 2002). For all of them, higher levels of sexual

satisfaction were associated with higher levels of psychological health and

other well-being-related measures.

Of all the things that influence well-being, one might question the impor-

tance of sex. The 2007 Durex Global Sexual Well-Being Survey showed that

the typical adult around the world only has sex once a week with foreplay and

intercourse averaging a mere 36 min (Durex, 2007; Wylie, 2009). Despite

this, Kahneman, Krueger, Schkade, Schwarz, and Stone (2004) found that

intimate relations are the most positively evaluated of all daily activities.

Blanchflower and Oswald (2004) add to this that the effect of sex on happi-

ness is statistically well determined, monotonic, and large, especially for

individuals under age 40 (p. 411).

The Moderating Effects of Sexual Activity Level on the

Relationship Between Sexual Satisfaction and Psychological

Health

Sexual satisfaction was a significant predictor of psychological health but

only for the sexually abstinent group. In other words, the relationship between

sexual satisfaction and psychological health is significant for the group whom

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UQ Library on March 13, 2015

58 The Prison Journal 95(1)

we believe were experiencing greater reactance due to their lack of choice in

their sexual behaviors. This is the first time that this result has been encoun-

tered in prison inmates. However, this finding is consistent with RT (Brehm

& Brehm, 1981) and other results found in non-prison populations whose

freedom to choose has been reduced or eliminated due to constraining situa-

tions such as the presence of sexual dysfunctions (Lau et al., 2005; Ventegodt,

1998), physical disabilities (Taleporos & McCabe, 2002), amputations

(Walters & Williamson, 1998), and having endured germ-cell tumor therapy

(Fegg et al., 2003).

The interviewers observations and the data gathered from this and another

of our previous studies (Carcedo, 2005) have relevance for understanding the

obtained interaction. Inmates who have not had sex for a long time made

more references to terms and adjectives related to sexual well-being and

expressed more anger (a concept-related to reactance) than did the inmates

who have had sex in the last 6 months. We suspect that what inmates discuss

reflects the importance they attribute to things; that is, we believe that those

who are sexually abstinent due to the conditions of prison life see sex as more

crucial to their well-being than do non-sexual-abstinent inmates. Thus, flow-

ing from these ideas and supporting our results, sexual satisfaction may be

more central for the psychological health of sexually abstinent inmates.

Notwithstanding, this result needs to be further investigated not only in prison

inmates but also in other populations with sexual problems in relation with

other individuals without these issues. The scarcity of empirical evidence

regarding the heterosexual desires and behaviors of inmates makes it espe-

cially important to focus on such populations in future studies.

The stronger relationship between sexual satisfaction and psychological

well-being among the sexually abstinent group also complements themes in

the early prison literature. The authors of these early studies discussed the

possible negative consequences of sexual abstinence for inmates health

(Levenson, 1983; Linville, 1981; Neuman, 1982; Snchez, 1995). As conju-

gal visits within prisons were even rarer than they are today, these authors

presumably were referring to inmates who had not had sex for a long time.

The present findings imply that it is for such sexually deprived inmates that

the negative mental health consequences are most pronounced, not for

inmates with greater access to and involvement in heterosexual activity.

This sexual deprivation could increase the desire for having sexual rela-

tionships, thus intensifying the impact of sexual satisfaction on psychological

health, as RT (Brehm & Brehm, 1981) posits. Thus, RT can explain why

higher levels of sexual satisfaction were associated with higher levels of psy-

chological health, although only for the inmates belonging to the sexually

abstinent group.

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UQ Library on March 13, 2015

Carcedo et al. 59

Future research pertaining to the sexual activity by sexual satisfaction interac-

tion might go in several directions. First, in cross-sectional studies, it would be

profitable to demonstrate that reactance is greater in populations such as inmates

whose members are prevented from having sex and that in sexually constrained

subgroups these reactance processes mediate between sexual satisfaction and

psychological health. Second, longitudinal studies of the inmates going from the

sexually abstinent group to the sexually active group (or vice versa) are war-

ranted. Consider those starting in the sexual-abstinent group: It would be valu-

able to demonstrate on a within-subject bases (a) that prior to the transition sexual

satisfaction is associated with psychological health but this association is non-

significant afterward, and (b) that sexual needs are highly important prior to the

transition but decline in importance after the transition. Third, it would be valu-

able to isolate a group of inmates who have not had sexual relationships for a long

time. If our analysis is correct, there should still be a strong sexual satisfaction/

psychological health association for this unique population. A final area for future

research might be efforts to apply RT to other deprivations of prison life.

Some heterosexually abstinent participants in this study reported relatively

higher levels of sexual satisfaction and psychological health. To fully under-

stand this, it would be beneficial to study why some inmates adjust better than

others to sexual deprivation. For instance, individuals who have had fairly nega-

tive sexual experiences in the past might not have been very interested in sex, or

individuals for whom sexual abstinence is a positive value might interpret this

situation in a more positive way, or some people may be generally more positive

in their outlook such that they judge both their sexual situation and their well-

being through positive lens. In this sense, sexual deprivation may not be consid-

ered and experienced by these individuals as necessarily negative.

The Moderating Effect of Gender on the Relationship Between

Sexual Satisfaction and Psychological Health, and Control

Variables

The moderating effect of gender on the relationship between sexual satisfac-

tion and psychological health was not found, contradicting previous non-

prison studies (Laumann et al., 2006; Taleporos & McCabe, 2002). An

association between being more sexually satisfied and having greater psy-

chological health was obtained, however, consistent with the only prison

study of which we are aware that has dealt with this relationship (Carcedo

et al., 2008). In that particular study, sexual satisfaction predicted psychologi-

cal health for both genders, although the percentage of explained variance

was slightly higher for women. Carcedo et al.s study did not statistically test

whether that difference was significant. However, the conditional effect of

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UQ Library on March 13, 2015

60 The Prison Journal 95(1)

sexual satisfaction in the current investigation supports and refines Carcedo

et al.s work, since a group of control variables were analyzed simultaneously

with sexual satisfaction to predict psychological health. This result is also

consistent with previous RT findings, because research in psychological reac-

tance has detected gender differences only in an insignificant portion of the

reactance literature. In this sense, psychological reactance is not gender-

specific (Brehm & Brehm, 1981).

Limitations of the Present Study

Although we think that the sample size is quite large for an interview study

focused on an uncommon topic in prison and sexuality research, the statisti-

cal power for detecting effects, especially interaction effects, is still low.

Thus caution is needed in generalizing these results to the whole prison popu-

lation. Even more caution is needed in making generalizations to the non-

prison population. More research is needed in this regard. In addition, in light

of the uneven ratio of women to men within the two sexual activity groups,

we used the model comparisons framework articulated by Appelbaum and

Cramer (1974) and Maxwell and Delaney (1990) to deal with non-orthogonality.

Still future research is needed to check if similar results are found using com-

pletely balanced or orthogonal designs.

Another limitation of this study is that causation is difficult to infer due to

the correlational design. In a recent issue of the Journal of Sex & Marital

Therapy, Balon (2008) stated that psychological health may lead to sexual

satisfaction or sexual satisfaction and psychological health may have a circu-

lar relationship. However, in the same issue, Rosen and Bachmann (2008)

used empirical evidence and the perspective of a positive psychology to argue

for a directional relationship from sexual satisfaction to well-being.

Finally, despite the interviewer stressing the confidentiality and anonym-

ity of the study, homosexual contacts might have been underreported by the

inmates. In evaluating that possibility it is important to keep in mind that all

the inmates indicated they felt very comfortable during the interview and

they disclosed other sensitive information about themselves. Future research-

ers might employ more subtle ways of seeking information about homosex-

ual acts to determine if their true rate is higher in Spanish prisons than was

reported to the current research team.

Implications and Conclusions

Finally, these results have practical implications. Allowing inmates to have

romantic and sexual relationships with other inmates in prison appears to be

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UQ Library on March 13, 2015

Carcedo et al. 61

a valuable option for them, especially for those without a partner. Therefore,

having this as a prison policy may be beneficial for inmates sexual satisfac-

tion and psychological health. It may also benefit prisons: Inmates scoring

higher on psychological health have lower levels of misconduct at prison

(Wright, Salisbury, & Van Voorhis, 2007). Furthermore, lower levels of per-

sonal distress, a psychological health-related concept, have been significantly

associated with lower recidivism rate after inmates are released (Gendreau,

Little, & Goggin, 1996). Thus, we would point out that housing men and

women in the same prison can be beneficial, particularly if they are allowed

to start romantic relationships and maintain sexual relationships. Nevertheless,

education and policies to control sexual risks (e.g., unwanted pregnancies,

STDs, and sexual-partner violence) also have to be developed. For example,

in the prison where this study was conducted, the prison gives condoms to

inmates every month, offers some sexual education courses, tests inmates for

STDs and HIV, supervises their relationships to prevent any possible sort of

violence, and takes into consideration the inmates criminal records.

Historically, as well as now, sexuality has all too often been left in the

shadows rather than illuminated. Myths, false beliefs, and fears have always

surrounded this topic. If we add prison, the resultant equation is even more

scary, and misconceptions are likely to proliferate. Prison systems con-

cerned with inmates needs have offered some alternatives to sexual depriva-

tion such as conjugal visits. For inmates who have no partner, however,

conjugal visits are not a viable solution. Systems such as the one we studied

that allow inmates to form relationships are needed.

Correctional systems focused on punishing inmates have adopted an easy

solution: deprivation. Independent of the prison system and the cultural view

of sexuality, the fact is that sexual satisfaction seems to be associated with

psychological health, especially for those who have not had sex for a long

time. We advocate for more research in this area, but if the present results are

supported in the future, the implication for prison policies appears clear:

Sexual activity enhances psychological health and, among those without a

partner, being satisfied with ones sexual situation enhances psychological

health. The former effect appears more powerful than the latter. Rather than be

guided by our own (mis)conceptions, let us be guided by tested knowledge.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to the regional education authority of Castilla y Len and

the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports of Spain which provided two grants, one

to carry out this study (ref. SA007B08), and another through the Jos Castillejo pro-

gram to support the stay of the first author in the Department of Human Development

and Family Studies at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. The first author

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UQ Library on March 13, 2015

62 The Prison Journal 95(1)

is also grateful to this department for their support and help with this project. Finally,

he wants to thank Ioana Scripa for her help in preparing the manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research,

authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research,

authorship, and/or publication of this article: The authors received financial support

for the research from the regional education authority of Castilla y Len (Junta de

Castilla y Len, ref. SA007B08). The first author also received a grant from the

Ministry of Educacin, Culture and Sports of Spain to support his stay in the

Department of Human Development and Family Studies at the University of North

Carolina at Greensboro.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting

interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Appelbaum, M. I., & Cramer, E. M. (1974). Some problems in the nonorthogonal

analysis of variance. Psychological Bulletin, 81, 335-343.

Balon, R. (2008). In pursuit of (sexual) happiness and well-being: A response. Journal

of Sex & Marital Therapy, 34, 298-301.

Blanchflower, D., & Oswald, A. (2004). Money, sex and happiness: An empirical

study. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 106, 393-415.

Brehm, J. W. (1966). A theory of psychological reactance. New York, NY: Academic

Press.

Brehm, S. S., & Brehm, J. W. (1981). Psychological reactance: A theory of freedom

and control. New York, NY: Academic Press.

Carcedo, R. J. (2005). Necesidades sociales, emocionales y sexuales. Estudio en

un centro penitenciario [Social, emotional, and sexual needs: Study in a peni-

tentiary]. Salamanca, Spain: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de

Salamanca.

Carcedo, R. J., Lpez, F., Orgaz, M. B., Toth, K., & Fernndez-Rouco, N. (2008).

Men and women in the same prison: Interpersonal needs and psychological health

of prison inmates. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative

Criminology, 52, 641-657.

Carcedo, R. J., Perlman, D., Lpez, F., & Orgaz, M. B. (2012). Heterosexual roman-

tic relationships, interpersonal needs, and quality of life in prison. The Spanish

Journal of Psychology, 15, 187-198.

Carcedo, R. J., Perlman, D., Orgaz, M. B., Lpez, F., Fernndez-Rouco, N., &

Faldowski, R. (2011). Heterosexual romantic relationships inside of prison:

Partner status as predictor of loneliness, sexual satisfaction, and quality of life.

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UQ Library on March 13, 2015

Carcedo et al. 63

International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 55,

898-924.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regres-

sion/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Mahwah, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum.

Cramer, E. M., & Appelbaum, M. I. (1980). Nonorthogonal analysis of variance

Once again. Psychological Bulletin, 87, 51-57.

Das, A. (2007). Masturbation in the United States. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy,

33, 301-317.

Das, A., Parish, W. L., & Laumann, E. O. (2009). Masturbation in urban China.

Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38, 108-120.

DiTommaso, E., Brannen, C., & Best, L. A. (2004). Measurement and validity char-

acteristics of the short version of the Social and Emotional Loneliness Scale for

adults. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 64, 99-119.

Durex (2007). Sexual wellbeing global survey. Retrieved from http://www.durex.

com/en-ph/sexualwellbeingsurvey/pages/default.aspx

Fegg, M. J., Gerl, A., Vollmer, T. C., Gruber, U., Jost, C., Meiler, S., & Hiddemann,

W. (2003). Subjective quality of life and sexual functioning after germ-cell

tumour therapy. British Journal of Cancer, 89, 2202-2206.

Gendreau, P., Little, T., & Goggin, C. (1996). A meta-analysis of the predictors of

adult offender recidivism: What works! Criminology, 34, 575-607.

Goodman, L. A. (1961). Snowball sampling. Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 32,

148-170.

Hayes, A. F., & Matthes, J. (2009). Computational procedures for probing interac-

tions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behavior

Research Methods, 41, 924-936.

James, D. J., & Glaze, L. E. (2006). Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates

[Electronic Version]. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. Retrieved

from http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mhppji.pdf

Kahneman, D., Krueger, A., Schkade, D., Schwarz, N., & Stone, A. (2004). A survey

method for characterizing daily life experience: The day reconstruction method.

Science, 306, 1776-1780.

Lacombe, E. (1997). Limpact de lincarcration sur lexpression de la sexualit dun

groupe en milieu correctionnel ouvert: Pistes dintervention [The impact of incar-

ceration on the sexual expression of an open prison regime group: Clues for the inter-

vention]. (Unpublished masters thesis). University of Montreal, Qubec, Canada.

Langstrom, N., & Hanson, R. K. (2006). High rates of sexual behavior in the general

population: Correlates and predictors. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 35, 37-52.

Lau, J. T., Wang, Q., Cheng, Y., & Yang, X. (2005). Prevalence and risk factors

of sexual dysfunction among younger married men in a rural area in China.

Urology, 66, 616-622.

Laumann, E. O., Paik, A., Glasser, D. B., Kang, J.-H., Wang, T., Levinson, B., . . .

Gingell, C. (2006). A cross-national study of subjective sexual well-being among

older women and men: Findings from the global study of sexual attitudes and

behaviors. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 35, 145-161.

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UQ Library on March 13, 2015

64 The Prison Journal 95(1)

Levenson, L. (1983). Sexual attitudes of males in a protected environment. Journal

of the American Society of Psychosomatic Dentistry and Medicine, 30, 135-136.

Lindquist, C. H. (2000). Social integration and mental well-being among jail inmates.

Sociological Forum, 15, 431-455.

Lindquist, C. H., & Lindquist, C. A. (1997). Gender differences in distress: Mental

health consequences of environmental stress among jail inmates. Behavioral

Sciences & the Law, 15, 503-523.

Linville, S. L. (1981). Assessing sexual attitudes and behaviors of incarcerated males

in a minimum security institution. Morgantown: West Virginia University.

Lucas, R. (1998). Versin espaola del WHOQOL [Spanish version of the WHOQOL].

Madrid, Spain: Ergon.

Maeve, M. K. (1999). The social construction of love and sexuality in a womans

prison. Advances in Nursing Science, 21, 46-65.

Maxwell, S. E., & Delaney, H. D. (1990). Designing experiments and analyzing data:

A model comparison perspective. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Mehta, C., & Patel, N. (2002). StatXact 5: Statistical software for exact nonparametric

inference (User Manual Vol. 1). Cambridge, MA: Cytel Software Corporation.

Neter, J., Kutner, M. H., Nachtsheim, C., & Wasserman, W. (1996). Applied linear

statistical models. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

Neuman, E. (1982). El problema sexual en las crceles [The sexual problem in pris-

ons]. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Editorial Universidad.

Nicolosi, A., Moreira, E. D., Villa, M., & Glasser, D. B. (2004). A population study

of the association between sexual function, sexual satisfaction and depressive

symptoms in men. Journal of Affective Disorder, 82, 235-243.

Pardue, A., Arrigo, B. A., & Murphy, D. S. (2011). Sex and sexuality in womens

prisons: A preliminary typological investigation. The Prison Journal, 91,

279-304.

Rosen, R. C., & Bachmann, G. A. (2008). Sexual well-being, happiness, and satis-

faction, in women: The case for a new conceptual paradigm. Journal of Sex &

Marital Therapy, 34, 291-297.

Snchez, M. G. (1995). La abstinencia sexual forzosa de las reclusas en los estab-

lecimientos carcelarios de Venezuela [Forced sexual abstinence of female prison

inmates in Venezuela]. Coro: Composicin Comput.

Snell, W. E. (1995). The Multidimensional Self-Concept Questionnaire. In C. M.

Davis, W. L. Yarber, R. Bauserman, G. E. Schreer & S. L. Davis (Eds.), Handbook

of sexuality-related measures (pp. 521-524). London, England: Sage.

Taleporos, G., & McCabe, M. P. (2002). The impact of sexual esteem, body esteem,

and sexual satisfaction on psychological well-being in people with physical dis-

ability. Sexuality and Disability, 20, 177-183.

Toch, H. (1977). Living in prison: The Ecolology of survival. New York: Free Press.

Ventegodt, S. (1998). Sex and quality of life in Denmark. Archives of Sexual Behavior,

27, 295-307.

Walters, A. S., & Williamson, G. M. (1998). Sexual satisfaction predicts quality of

life: A study of adult amputees. Sexuality and Disability, 16, 103-115.

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UQ Library on March 13, 2015

Carcedo et al. 65

Wright, E. M., Salisbury, E. J., & Van Voorhis, P. (2007). Predicting the prison

misconducts of women offenders: The importance of gender-responsive needs.

Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 23, 310-340.

Wylie, K. (2009). A global survey of sexual behaviours. Journal of Family &

Reproductive Health, 3(2), 39-49.

Zamble, E., & Porporino, F. J. (1988). Coping, behaviour and adaptation in prisons.

New York: Springer-Verlag.

Author Biographies

Rodrigo J. Carcedo is an associate professor in the Department of Developmental

and Educational Psychology, University of Salamanca. His research focuses on inter-

personal and sexual needs related to prisoners and other socially excluded popula-

tions. His research has been published in The International Journal of Offender

Therapy & Comparative Criminology, The Spanish Journal of Psychology,

Adicciones, Behavioral Psychology, and Sex Education: Sexuality, Society and

Learning.

Daniel Perlman is a professor of human development & family studies, University of

North Carolina at Greensboro. He is co-author of a textbook, Intimate Relationships,

and co-editor of the Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships. He has also

published his work in prestigious journals such as Criminal Justice and Behavior,

Journal of Social Issues, Archives of Sexual Behavior, Personality and Social

Psychology Bulletin, and Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. He has also

served as president of four professional associations.

Flix Lpez is professor in the Department of Developmental and Educational

Psychology, University of Salamanca. A senior scientist, his research interests are

sexuality and interpersonal relationships needs theory, infancy, adolescence, and

socially excluded populations. He has recently published in The International Journal

of Offender Therapy & Comparative Criminology, The Spanish Journal of Psychology,

Psicothema, and Infancia y Aprendizaje.

M. Begoa Orgaz is an associate professor in the Department of Methodology of

Behavioral Sciences, University of Salamanca. A data analyst, her most recent publi-

cations have appeared in The International Journal of Offender Therapy &

Comparative Criminology, Behavioral Psychology, BMC Pediatrics Journal, and

Computers in Human Behavior.

Noelia Fernndez-Rouco is an assistant professor in the Department of Education,

University of Cantabria. Her research interests include well-being in transsexual,

homosexual, and prison inmate populations, and needs theory. Her most recent pub-

lications are a book and an article in The International Journal of Offender Therapy

and Comparative Criminology.

Downloaded from tpj.sagepub.com at UQ Library on March 13, 2015

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Dirty Slang DictionaryDocument20 pagesDirty Slang DictionaryMr. doody82% (33)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Myth of Matriarchal PrehistoryDocument193 pagesThe Myth of Matriarchal PrehistoryFer González Blanco93% (14)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Resolution RapeDocument8 pagesResolution Rapekoey100% (1)

- BDSM... Knowledge 1Document2 pagesBDSM... Knowledge 1Samlove02No ratings yet

- Sex - The Grafenberg Spot FaqDocument3 pagesSex - The Grafenberg Spot FaqCiceroFilosofiaNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Freud, Erikson, Piaget, Kohlberg Theories: Developmental PhenomenaDocument3 pagesComparison of Freud, Erikson, Piaget, Kohlberg Theories: Developmental PhenomenaNorashia MacabandingNo ratings yet

- People v. Daniel (IGNACIO)Document1 pagePeople v. Daniel (IGNACIO)Christian IgnacioNo ratings yet

- Rule 103 v. Rule 108Document10 pagesRule 103 v. Rule 108PmbNo ratings yet

- Persons HW # 6Document19 pagesPersons HW # 6Pouǝllǝ ɐlʎssɐNo ratings yet

- INCREASE DEPRESSION AND ANXIETY CONDITION DUE TO COVID-19 OUTBREAK - Compressed PDFDocument23 pagesINCREASE DEPRESSION AND ANXIETY CONDITION DUE TO COVID-19 OUTBREAK - Compressed PDFTitah RahayuNo ratings yet

- Poster Case Report Edit AkhirDocument1 pagePoster Case Report Edit AkhirTitah RahayuNo ratings yet

- WHODAS2.0 36itemsSELFDocument4 pagesWHODAS2.0 36itemsSELFendriNo ratings yet

- F - Flyer 2nd - Konas Pdskji 2019Document3 pagesF - Flyer 2nd - Konas Pdskji 2019Titah RahayuNo ratings yet

- Pain Assessment Scales PDFDocument10 pagesPain Assessment Scales PDFArio Wahyu PamungkasNo ratings yet

- Pain Assessment Scales PDFDocument10 pagesPain Assessment Scales PDFArio Wahyu PamungkasNo ratings yet

- Relation Dyration of Marriage PDFDocument7 pagesRelation Dyration of Marriage PDFTitah RahayuNo ratings yet

- Cognitive and Other Predictors of Change in Quality of Life One Year After Treatment For Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia or Myelodysplastic SyndromeDocument4 pagesCognitive and Other Predictors of Change in Quality of Life One Year After Treatment For Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia or Myelodysplastic SyndromeTitah RahayuNo ratings yet

- Escala GarfDocument1 pageEscala GarfAna Claudia PoiteNo ratings yet

- 1752-1947!5!17 Trombosis Arteri MesenterikaDocument5 pages1752-1947!5!17 Trombosis Arteri MesenterikaTitah RahayuNo ratings yet

- 11 - 206memahami DispareuniaDocument8 pages11 - 206memahami DispareuniaResti Puteri Apriyuslim0% (1)

- Antipsikotik Ke Bayi PDFDocument4 pagesAntipsikotik Ke Bayi PDFTitah RahayuNo ratings yet

- Glenoid Size, Inclination, and Version: An Anatomic Study: R. Sean Churchill, MD, John J. Brems, MD, and Helmuth KotschiDocument6 pagesGlenoid Size, Inclination, and Version: An Anatomic Study: R. Sean Churchill, MD, John J. Brems, MD, and Helmuth KotschiTitah RahayuNo ratings yet

- Screech Owl Nest BoxDocument1 pageScreech Owl Nest Box1940LaSalleNo ratings yet

- 2017Document107 pages2017GEGAYNo ratings yet

- CDC Hiv Safer Sex 101Document1 pageCDC Hiv Safer Sex 101api-376088129No ratings yet

- Official Lust Man Standing Guide v0.11Document41 pagesOfficial Lust Man Standing Guide v0.11Pat LannyNo ratings yet

- Schooling Walkthrough v07Document23 pagesSchooling Walkthrough v07ran domNo ratings yet

- Intersex People Are Individuals Born With Any of Several Variations inDocument1 pageIntersex People Are Individuals Born With Any of Several Variations inDave SorianoNo ratings yet

- CtenophoraDocument23 pagesCtenophoraAnonymous eOcg87KnNo ratings yet

- Senate Election: ResultsDocument16 pagesSenate Election: ResultsThe University Daily KansanNo ratings yet

- Gay Rights-Final Research PaperDocument7 pagesGay Rights-Final Research Paperapi-239846657100% (1)

- Thomas Minar Arrest ReportDocument14 pagesThomas Minar Arrest ReportIndiana Public Media NewsNo ratings yet

- PP VS RamosDocument2 pagesPP VS RamosJacqueline WadeNo ratings yet

- Gelect 2: Gender and Society: OrientationDocument192 pagesGelect 2: Gender and Society: OrientationNorman Louis CadaligNo ratings yet

- Prop 57 - Nonviolent CrimesDocument6 pagesProp 57 - Nonviolent CrimesLakeCoNewsNo ratings yet

- Meiosis FoldableDocument48 pagesMeiosis FoldablejojopebblesNo ratings yet

- Module 4 (Basics of Sti, Hiv & Aids)Document37 pagesModule 4 (Basics of Sti, Hiv & Aids)Marky RoqueNo ratings yet

- 'Gay Gaze' and The Refashioning of Queer Imaginaries in Digital IndiaDocument10 pages'Gay Gaze' and The Refashioning of Queer Imaginaries in Digital IndiafeepivaNo ratings yet

- Elevated Risk of Blood Clots in Women Taking Birth Control Containing Drospirenone, Study ShowsDocument3 pagesElevated Risk of Blood Clots in Women Taking Birth Control Containing Drospirenone, Study ShowsJomerlyn AbaricoNo ratings yet

- Maine's Shameful State Secret Child Sex AbuseDocument2 pagesMaine's Shameful State Secret Child Sex AbuseLori HandrahanNo ratings yet

- 04 - The Hierophant - Cindy Spencer Pape - Teach Me (Geek Love 3)Document102 pages04 - The Hierophant - Cindy Spencer Pape - Teach Me (Geek Love 3)AdrianaMihai100% (1)

- Philippine Eagle: TaxonomyDocument5 pagesPhilippine Eagle: TaxonomyCJ AngelesNo ratings yet

- SOC134 Cheat Sheet 3Document5 pagesSOC134 Cheat Sheet 3Aman Kumar TrivediNo ratings yet