Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dat. 030 NEU

Uploaded by

Srijana RegmiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dat. 030 NEU

Uploaded by

Srijana RegmiCopyright:

Available Formats

Article 30

Mental element

1. Unless otherwise provided, a person shall be criminally responsible

and liable for punishment for a crime within the jurisdiction of the Court

only if the material elements are committed with intent and knowledge.

2. For the purposes of this article, a person has intent where:

(a) In relation to conduct, that person means to engage in the

conduct;

(b) In relation to a consequence, that person means to cause that

consequence or is aware that it will occur in the ordinary course

of events.

3. For the purposes of this article, "knowledge" means awareness that a

circumstance exists or a consequence will occur in the ordinary course of

events. "Know" and "knowingly" shall be construed accordingly.

Literature:

Roger S. Clark, The Mental Element in International Criminal Law: The Rome Statute of the International

Criminal Court and the Elements of Crime, 12 CRIM. L.F. 291 (2001); Albin Eser, Mental Elements Mistake of

Fact and Mistake of Law, in: Antonio Cassese/Paola Gaeta/John R.W.D. Jones (eds.), THE ROME STATUTE OF THE

INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT: A COMMENTARY 889, Vol. I (2002); Mohamed Elewa Badar, Mens rea

Mistake of Law & Mistake of Fact in German Criminal Law: A Survey for International Criminal Tribunal, 5

INT'L C. L. REV. 203 (2005); Kirsten M. F. Feith, The Mens Rea of superior responsibility as developed by ICTY

jurisprudence, 14 LEIDEN J. INT'L L. 617 (2001); Otto Triffterer, The new International Criminal Law Its

General Principles establishing Individual Criminal Responsibility, in: Kalliopi Koufa (ed.), THESAURUS

ACROASIUM, THE NEW INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL LAW 639, Vol. XXXII (2003); id., "Command Responsibility"

crimen sui generis or participation as "otherwise provided" in Article 28 Rome Statute?, in: Jrg Arnold et al.

(eds.), MENSCHENGERECHTES STRAFRECHT, FESTSCHRIFT FR ALBIN ESER ZUM 70. GEBURTSTAG 91 (2005); id.,

Command Responsibility, Article 28 Rome Statute, an Extension of Individual Criminal Responsibility for Crimes

Within the Jurisdiction of the Court Compatible with Article 22, nullum crimen sine lege?, in: Otto Triffterer,

GEDCHTNISSCHRIFT FR THEO VOGLER 213 (2004); Claus Roxin, STRAFVERFAHRENSRECHT (25th ed. 1998);

Gerhard Werle, PRINCIPLES OF INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL LAW (2005).

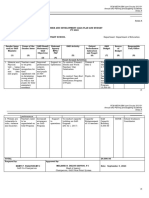

Contents: margin No.

A. Introduction/General Remarks 1. "conduct"...................................... 17

1. Historical development........................ 1 2. "means to engage in the

2. Purpose................................................. 2 conduct" ....................................... 19

3. Scope.................................................... 3 IV. Sub-paragraph 2 (b)

4. Protected values ................................... 4 1. "consequence".............................. 20

B. Analysis and interpretation of elements 2. "means to cause that

I. Paragraph 1 consequence"................................ 21

1. "criminally responsible and 3. "aware that it will occur in the

liable for punishment".................. 5 ordinary course of events" ........... 22

2. "material elements"...................... 6 V. Paragraph 3

3. "committed" ................................. 7 1. "For the purposes of this article" . 24

4. "intent and knowledge"................ 9 2. "awareness that a circumstance

5. "Unless otherwise provided" ....... 14 exists" ........................................... 25

II. Paragraph 2 3. "awareness that ... a

1. "For the purposes of this article" . 16 consequence will occur in the

III. Sub-paragraph 2 (a) ordinary course of events" ........... 28

A. Introduction/General Remarks

1. Historical development

The Draft Statute for an International Criminal Court, contained in the Report of the 1

International Law Commission on the Work of its Forty-Sixth Session, did not contain a

provision concerning mental elements nor moral culpability1. In its 1995 Report, the Ad Hoc

1 1994 ILC Draft Statute.

Donald K. Piragoff/Darryl Robinson 849

article 30 Part 3. General principles of criminal law

Committee on the Establishment of an International Criminal Court2 noted that many

delegations expressed support for the inclusion in the Statute of provisions on general principles

of criminal law, including provisions on mens rea. During the sessions in 1996 of the

Preparatory Committee on the Establishment of an International Criminal Court, a number of

proposals were made regarding the insertion of a set of general principles, which included

various proposals concerning mens rea or mental elements3. These proposals included

provisions similar to those finally adopted by the Rome Conference, as well as proposals

concerning other possible mental elements, such as specific intent, wilful blindness, recklessness

and dolus eventualis. These proposals were further discussed by the Preparatory Committee at

its session in February 1997 and a number of decisions were taken4, which resulted in a draft

provision of narrower scope that was very similar to that finally adopted by the Rome

Conference in 19985.

2. Purpose

2 A general view was expressed in the Preparatory Committee on the Establishment of an

International Criminal Court that "since there could be no criminal responsibility unless mens

rea was proved, an explicit provision setting out all the elements involved should be included in

the Statute"6. A clear understanding of the general legal framework in which the court would

operate was important for the Court, States Parties and the accused so as to provide guidance,

predictability and certainty, and to promote consistent jurisprudence on fundamental questions,

including the issue of moral culpability or mens rea7.

3. Scope

3 Despite the desire of the Preparatory Committee that all the mental elements should be set

out in the Statute, these elements are not contained in one article. Article 30 only refers

specifically to "intent" and "knowledge". With respect to other mental elements, such as certain

forms of "recklessness" and "dolus eventualis", concern was expressed by some delegations that

various forms of negligence or objective states of mental culpability should not be contained as a

general rule in article 30. Their inclusion in article 30 might send the wrong signal that these

forms of culpability were sufficient for criminal liability as a general rule. As no consensus

could be achieved in defining these mental elements for the purposes of the general application

of the Statute, it was decided to leave the incorporation of such mental states of culpability in

individual articles that defined specific crimes or modes of responsibility, if and where their

incorporation was required by the negotiations. Therefore, other relevant mental elements are to

be found within the specific definition of crimes8 or other general principles of criminal law9

contained in the Statute. Thus, the opening words of paragraph 1 of article 30 ("Unless

otherwise provided"), recognise that mental elements might also be provided elsewhere in the

2 Ad Hoc Committee Report, p. 19.

3 1996 Preparatory Committee II, p. 9293.

4 Preparatory Committee Decisions Feb. 1997, p. 27.

5 For an account of the history of the negotiations on article 30, see: P. Saland, International Criminal Law

Principles, in: R. S. Lee (ed.), THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT, THE MAKING OF THE ROME

STATUTE: ISSUES, NEGOTIATIONS, RESULTS 189 (1999); and R. S. Clark, The Mental Element in

International Criminal Law: The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court and the Elements of

Crime, 12 CRIM. L.F. 291, 295316 (2001).

6 1996 Preparatory Committee I, p. 45.

7 Ad Hoc Committee Report, p. 19.

8 E.g., "wilful" or "wilfully" in article 8 para. 2 (a), or "treacherously" in article 8 paras. 2 (b) (xi) and (e) (ix).

9 E.g., "with the aim of furthering the criminal activity or criminal purpose of the group", in article 25 para. 3

(d) (i); "knew or, owing to the circumstances at the time, should have known in article 28 lit. a (i); or knew,

or consciously disregarded" in article 28 lit. b (i).

850 Donald K. Piragoff/Darryl Robinson

Mental element article 30

Statute, including in the elaboration of the Elements of Crimes, pursuant to article 9, provided

that these are consistent with the Statute.

Paragraphs 2 and 3 of article 30 provide definitions of "intent" and "knowledge". These

provisions describe the meaning of these terms and the degree of mental culpability or mens rea

that is required. For example, in order to intend conduct, a person must "mean" to engage in

conduct; it is not sufficient if the conduct was brought about carelessly. To know or have

knowledge of a circumstance, means to have "awareness" that it exits; mere suspicion is not

sufficient (unless it amounts to wilful blindness or some other high degree of awareness or

advertence to the existence of the circumstance).

Paragraph 1 of article 30 applies these definitions of "intent" and "knowledge" to the

material elements of the definitions of crimes in the Statute. The exact scope of this application,

however, has to be inferred for each crime depending on the specific material elements set out in

the definition of the crime and in light of the proviso to paragraph 1 ("Unless otherwise

provided"), and paragraph 2 ("For the purposes of this article").

4. Protected values

Many legal historians are of the view that prior to the twelfth century a person could be held 4

criminally liable merely if the persons conduct caused harm, regardless of any blameworthy

state of mind. Under the influence of Canon law and Roman law a requirement for some element

of moral blameworthiness a guilty mind was imposed by the courts. This requirement has

been expressed in the Latin maxim: actus non facit reum nisi mens sit rea10. It is now a basic

requirement of modern legal systems.

B. Analysis and interpretation of elements

I. Paragraph 1

1. "criminally responsible and liable for punishment"

The modes of commission and of participation by which a person shall be "criminally 5

responsible and liable for punishment for a crime within the jurisdiction of the Court" are

outlined in article 25 para. 3. These various modes of criminal responsibility (such as

"commits", "orders, solicits or induces", "aids, abets, or otherwise assists", "in any other way

contributes to the commission", "incites" and "attempts") must, by virtue of article 30, be

committed with intent and knowledge in order for a person to be criminally responsible and

liable for punishment. Despite the apparent assertion in article 25 that a person shall be

criminally responsible and liable for punishment if the persons conduct falls within any of the

subparagraphs of paragraph 3 of that article, the conditions of article 30 must also be fulfilled in

order to attach to that person any criminal responsibility and liability for punishment for a crime

within the jurisdiction of the Court. This is in accord with the Latin legal maximum: "actus non

facit reum nisi mens sit rea"11.

2. "material elements"

The "material elements" of a crime refer to the specific elements of the definition of the 6

crimes as defined in articles 5 to 8. This term refers to the conduct or action described in the

definition, any consequences that may be specified in addition to the conduct, and any factual

10 Translation: "An act does not make a person guilty of a crime, unless the persons mind be also guilty".

11 Ibid.

Donald K. Piragoff/Darryl Robinson 851

article 30 Part 3. General principles of criminal law

circumstances that qualify the definition12. This is confirmed by paragraphs 2 and 3 of article 30,

which define the meaning of "intent" or "knowledge" with respect to each of "conduct",

"consequences" and "circumstances". Although previous drafts had used the term "physical

elements", the term was changed in the Drafting Committee of the Rome Conference to

"material elements" in order to better reflect and connote the policy that the term incorporated

"conduct", "consequences" and "circumstances", which in most cases would be "physical" in

nature, but in many instances are not of such a character13.

The conduct of a crime includes a prohibited action14 or prohibited omission15 that is

described in the definition of a crime16. The consequences of a crime can refer either to a

completed result, such as the causing of death17, or the creation of a state of harm or risk of

harm, such as endangerment18, for example. The circumstances of a crime qualify the conduct

and consequences. They may, for example, describe the requisite features of the persons19 or

things20 mentioned in the conduct and consequence elements.

There are four special types of material element that warrant particular comment.

First, some material elements have a "legal" character; for example, requiring that a victim

be a "protected person" under the Geneva Conventions of 194921. Article 30 does not require

proof that the accused knew the relevant law or that he or she correctly completed such a legal

evaluation. Indeed, article 32 para. 2 affirms that a mistake of law as to the scope of the criminal

prohibition is not a ground for excluding criminal responsibility22. Accordingly, all that is

12 E.g., article 8 para. 2 (b) (x), defines a crime that contains all three types of material elements: conduct

("subjecting persons....to physical mutilation or to medical or scientific experiments"); circumstances ("who

are in the power of an adverse power";) and consequences ("which cause death to or seriously endanger the

health of such person or persons").

13 For example, in the Statute "conduct" sometimes refers to an omission (e.g., failure to do something),

"consequences" sometimes refers to a state of being rather than a physical result (e.g., a risk of harm

occurring), and "circumstances" sometimes refers to a quality or value of a physical object or a situation (e.g.,

legal status of a person or a building, or degree of harm or deprivation). For specific examples, see the text

accompanying infra notes 14 to 18.

Supra note 5, R. S. Clark, 299, 304305, queries how the change from "physical" to "material" came about,

and concludes that it did not convey a change of policy or substance by the Drafting Committee, but only a

reflection of drafting consistency. The present author recalls that the change was made for stylistic and

consistency reasons, as noted in the text of the present paper (see above).

The Elements of Crimes followed this same approach to material elements (conduct, consequences and

circumstances), often repeating the exact words of the Statute, and at other times adding elaborations from

international instruments or jurisprudence, but they were not intended to alter the overall definition of the

crime: see article 9 para. 3.

14 E.g., "killing", "causing serious bodily or mental harm", "inflictingconditions of life", "imposing

measures" and "forcibly transferring" in article 6.

15 E.g., "failed to take all necessary and reasonable measures" in article 28 lit. a (ii) and b (ii).

16 For greater discussion of the meaning of "conduct", see Part II, 1, below.

17 E.g., improper use of a flag of truce "resulting in death or serious personal injury" in article 8 para. 2 (b) (vii);

subjecting persons to physical mutilation or to medical or scientific experimentation "which cause death to

such person or persons" in article 8 para. 2 (b) (x).

18 E.g., subjecting persons to physical mutilation or to medical or scientific experimentation "whichseriously

endangers the health of such person or persons" in article 8 para. 2 (b) (x).

19 E.g., that the victims who are killed must be "members of the group" (article 6 (a)) or be "combatants"

(article 8 para. 2 (b) (vi)) or that the persons who are forcibly transferred must be "children of the group"

(article 6 (e)) or the persons who are compelled to take part in the operations of war must be "nationals of the

hostile party" (article 8 para. 2 (b) (xv)).

20 E.g., that the attacks or bombardment must be directed against "towns, villages, dwellings or buildings which

are undefended and which are not military objectives" (article 8 para. 2 (b) (v)) or "buildings dedicated to

religion, education, art, science" (article 8 para. 2 (b) (ix)).

21 Article 8 para. 2 (a).

22 An interesting question arises where the mistake of law is not related to the criminal prohibition itself, but

another area of law. For example, a bona fide mistake as to the "ownership" of particular property might

negate the mental element for the crime of pillage: see article 32 para. 2.

852 Donald K. Piragoff/Darryl Robinson

Mental element article 30

required is that the accused knew the factual elements that established this legal character (for

example, that the victim was affiliated with an adverse party)23.

Second, some material elements involve a normative aspect, or a "value judgment".

Examples include the requirement of "serious" injury to body or health, "severe" deprivation of

physical liberty, or "humiliating or degrading" treatment24. Such elements are similar to

elements of a legal character, as it is not required to show that the accused correctly completed

the normative evaluation. Otherwise, the accuseds subjective opinions would determine

whether a crime had been committed. For example, a perpetrator violently amputating the limbs

of a victim, and intending to do so, can hardly escape liability by arguing that he did not

consider the bodily harm to be "serious"25. The Court must decide if the material element is

satisfied (including whether the harm was "serious"), and decide whether the perpetrator had the

intent or awareness of the factual character establishing that "seriousness" (in this case, the

intent to amputate a limb). This rather obvious proposition accords with common sense as well

as the approach of national legal systems26, and is now confirmed in paragraph 4 of the General

Introduction to the Elements, which provides that "with respect to mental elements associated

with elements involve value judgment it is not necessary that the perpetrator personally

completed a particular value judgement, unless otherwise indicated"27.

Third, some material elements contain an adjectival phrase that incorporates a mental state.

Examples include inflicting conditions of life "calculated" to bring about the physical

destruction of a group and imposing measures "intended" to prevent births28. Do these refer to

the calculation or intentions of the accused or do they refer to an objective characterization of

the conditions or measures? Whether these hybrid elements are treated as mental elements or

material elements may have a bearing on the determination of culpability29. If what is required is

proof that there was such a "calculation" or "intent", then arguably this requirement would be

satisfied if it were shown that the accused so calculated or intended (i.e., mental element), or

that there was a broader calculation or intent, for example, among the planners, or evident from

the nature and scale of the acts (i.e., material element) and that the accused was aware of this

material element (i.e., knowledge of material element required by article 30).

Fourth, in the Elements of Crime some circumstance elements were identified as "contextual

elements", because they relate not to the conduct of the accused but rather to the broader

"context" that renders the crime an international crime. For war crimes, this is the existence of

an armed conflict; for crimes against humanity, it is the widespread or systematic attack against

a civilian population; and for genocide, it is the pattern of genocidal conduct30. As will be

explained below, reduced mental elements were considered appropriate in the Elements of

Crimes for contextual elements.

23 A possible deviation from this approach appears in the Elements of Crimes for article 8 para. 2 (b) (vii)

(improper use of a flag of truce), where the regulatory nature of these offences led delegations to include a

requirement that the perpetrator "knew or should have known of the prohibited nature of such use".

24 Article 8 para. 2 (iii), article 7 para. 1 (e), and article 8 para. 2 (b) (xxi), respectively. There is no hard and

fast rule to identify "value judgments", as this can depend on the circumstances. For example, an accused that

had been indoctrinated in hate propaganda could not escape liability by arguing that victims from a targeted

minority were not considered to be "persons".

25 Article 6 (b) of the Statute.

26 See e.g., a case of the Supreme Court of Canada, R. v. Finta [1994] 1 S.C.R. 701, 819 (accused must be

aware of the facts or circumstances that bring the acts within the definition of a crime against humanity, but

need not know that his actions were "inhumane").

27 Out of an abundance of caution, several provisions in the Elements nonetheless spell out the application of

this principle to particular elements: see, e.g., article 7 para. 1 (k), element 3.

28 Article 6 (c) and (d). See also the elements for article 8 para. 2 (a) (ii)-2 (war crime of biological

experiments): "the intent of the experiment was non-therapeutic" (emphasis added).

29 See: M. Kelt/H. von Hebel, General Principles of Criminal Law and the Elements of Crimes, in: R. S. Lee et

al. (eds.), THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT: ELEMENTS OF CRIMES AND RULES OF PROCEDURE 27

(2001).

30 See para. 7 of the General Introduction to the Elements, and the final element of each crime.

Donald K. Piragoff/Darryl Robinson 853

article 30 Part 3. General principles of criminal law

Finally, in addition to the material elements of a particular offence, preconditions for the

jurisdiction of the Court may also have to be proven where contentious31, but neither the Statute

nor any principle of international law require a mental element for such preconditions.

3. "committed"

7 The term "committed" clearly refers to the mode of participation in crime that is described in

sub-paragraph 3 (a) of article 25 (i.e., "commits such a crime"). The term, however, is also used

generically in a broader sense and also includes all of the other modes of criminal responsibility

described in article 25 sub-paras. 3 (b) to (f). This interpretation is supported by the discussion,

above, of the term "criminally responsible and liable for punishment".

8 For example, in the case of some modes of criminal responsibility in article 25 (such as

inciting others to commit genocide or attempting to commit a crime), not all of the physical or

material elements described in the definition of the crimes in articles 5 8 need actually be

committed. Nevertheless, there is a form of "commission" in respect of the material elements of

the definition of a crime by a person who undertakes one of the modes of criminal responsibility

described in article 25 paras. 3 (b) to (f), even if the actual intended, attempted or incited crime

is not carried out or completed. Therefore, the term "committed" refers to the commission of a

material element of a crime by any of the modes of criminal responsibility described in article

25 (a) to (f).

4. "intent and knowledge"

9 Each of the terms "intent" and "knowledge" is specifically defined in paragraphs 2 and 3 of

article 30, respectively. See below.

10 Prior to the February 1997 session of the Preparatory Committee, there had been some

debate as to whether these two terms should be disjunctive ("or") or conjunctive ("and")32. At

the February 1997 session, a decision was taken to use the conjunctive formulation, which was

subsequently adopted by the Rome Conference. This decision was based on the theory that, in

general, one cannot perform an action or cause a consequence intentionally unless one also has

knowledge of the circumstances in which that action or consequence was committed. Where a

relevant circumstance is not known to a person, the persons act is not intentional in the context

of that circumstance. For example, one cannot be said to intentionally attack or bombard a

civilian target, contrary to article 8 para. 2 (b) (v), unless one is aware of the circumstances that

render the civilian buildings "undefended" or "not military objectives". In result, "intent"

necessarily includes or requires "knowledge" of the relevant surrounding circumstances or

foresight of consequences. However, "knowledge" can exist independently of "intent", as one

can know that a circumstance exists or that a consequence will occur even if one does not intend

or wish that it exists or occurs. The conjunctive formulation in article 30 para. 1, ensures that

even where knowledge of a particular circumstance might be a separate element of a crime33, a

person cannot be criminally responsible and liable for punishment unless the other material

elements34 are also committed with intent.

This approach was subsequently confirmed in the Elements of Crimes, which distinguishes

between the crime as a whole and particular material elements. Paragraph 2 of the General

31 E.g., the location of the commission of a crime, the nationality of a perpetrator, the fact that a crime was

committed after the entry into force of the Statute, or the fact that a particular event falls within the scope of a

situation referred to the Court: see articles 1114.

32 E.g., 1996 Preparatory Committee II, p. 92.

33 E.g., article 7 para. 1 ("with knowledge of the attack"); article 8 para. 2 (b) (iv) ("in the knowledge that such

attack will cause incidental loss of life or injury to civilians").

34 E.g., article 7 para. 1 (intentionally committing the "following acts" as described in (a) to (k)); article 8 para.

2 (b) (vi) "intentionally launching an attack".

854 Donald K. Piragoff/Darryl Robinson

Mental element article 30

Introduction to the Elements reiterates the article 30 formulation that the material elements of a

crime (i.e. the elements considered collectively in forming the crime as a whole) must be

committed with "intent and knowledge". However, this does not mean that each particular

material element must be committed with both intent and knowledge. Indeed, this would

contradict article 30 paras. 2 and 3, which set out the relevant mental elements for each type of

material element. Therefore, with respect to particular mental elements, paragraph 2 of the

General Introduction to the Elements refers to "the relevant mental element, i.e. intent,

knowledge or both, set out in article 30" (emphasis added).

A question arises as to whether the conjunctive formulation changes existing international 11

jurisprudence35 that an accomplice (such as an aider and abettor) need not share the same mens

rea of the principal (e.g., an intent to kill), and that "a knowing participation in the commission

of an offence" or "awareness of the act of participation coupled with a conscious decision to

participate" is sufficient mental culpability for an accomplice. It is submitted that the

conjunctive formulation has not altered this jurisprudence, but merely reflects the fact that

aiding and abetting by an accused requires both knowledge of the crime being committed by the

principal and some intentional conduct by the accused that constitutes the participation. Even if

a strict literal reading of the conjunctive in paragraph 1 were made, such that an accomplice

must intend the consequence committed by the principal, the same interpretative result would

occur. Article 30 para. 2 (b), makes it clear that "intent" may be satisfied by an awareness that a

consequence will occur in the ordinary course of events. This same type of awareness can also

satisfy the mental element of "knowledge", as defined in article 30 para. 3. Therefore, if both

"intent" and "knowledge" are required on the part of an accomplice, these mental elements can

be satisfied by such awareness. Therefore, by either interpretation article 30 confirms the

existing international jurisprudence.

A number of the definitions of crime specifically require that the material elements be 12

"intentional" or be committed "intentionally"36. This is likely superfluous, given the general rule

in article 30. The specific presence of these terms is likely a product of the negotiation process

whereby certain delegations wished to make clear the intentional nature of the crimes before

they agreed to their inclusion in articles 7 and 8 or the terms are reflective of other international

instruments, such as the Geneva Conventions, which were used as the basis of the negotiations.

While there may be a surplusage in these instances, the significance of article 30 to these

provisions is that it also imports the element of "knowledge" into these definitions of crime.

The major significance of article 30, however, is its effect on definitions that do not 13

expressly specify a mental element. Although a particular definition of a crime may be silent as

to the requisite mental element, article 30 would import the mental elements of "intent and

knowledge" as being the mental elements required in order to render an accused criminally

responsible and liable for punishment for that particular crime.

Concerns were expressed by some delegations, particularly during the negotiation of the

Elements, as to the potential difficulties of proving mental elements. Such difficulties may be

mitigated if the Court adopts doctrines such as the principle of "wilful blindness" to be a type of

"knowledge". In addition, paragraph 3 of the General Introduction to the Elements of Crimes re-

affirms the elementary proposition that "the existence of intent and knowledge can be inferred

from relevant facts and circumstances"37.

35 Prosecutor v. Furundzija, Case No. IT-95-17/1-T, Judgement, Trial Chamber, 10 Dec. 1998, paras. 236241.

36 E.g., article 7 paras. 2 (b), (e), (f) and (h); article 8 paras. 2 (b) (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), (ix), (xxiv) and (xxv), and

paras. 2 (e) (i), (ii), (iii) and (iv).

37 See also Prosecutor v. Akayesu, Case No. ICTR-96-4-T, Judgment, Trial Chamber, 2 Sep. 1998, para 498

(intent may be inferred from presumptions of fact, intent may be inferred from context of perpetration of

acts); Prosecutor v. Kayishema, Case No.ICTR-95-1-T, Judgment, Trial Chamber, 21 May 1999, para 93

(intent can be inferred from words and deeds, patterns of purposeful action), affirmed, Prosecutor v.

Kayishema, Case No. ICTR-95-1-A, Judgment, Appeal Chamber, 1 June 2001, para 159.

Donald K. Piragoff/Darryl Robinson 855

article 30 Part 3. General principles of criminal law

5. "Unless otherwise provided"

14 This term performs two functions: first, it establishes the article 30 standard as the "default

rule" for all material elements, and second, it signals that there may be deviations from that

approach where otherwise provided.

The status of article 30 as the default rule was explicitly re-affirmed in the Elements, in order

to avoid the necessity of spelling out the mental element for every material element, particularly

where the application of article 30 is clear. Accordingly, paragraph 2 of the General Introduction

to the Elements explains, "[w]here no reference is made in the Elements of Crimes to a mental

element for any particular conduct, consequence or circumstance listed, it is understood that the

relevant mental element i.e., intent, knowledge or both, set out in article 30, applies". Thus, for

each material element listed, article 30 implicitly applies, and mental elements were articulated

only where there was a need to depart from the article 30 standard or to clarify a potential

ambiguity in its application.

The second function of the phrase is to signal that there may be deviations from the article

30 standard where otherwise provided. An issue that was not settled at the Rome Conference

was whether only the Rome Statute could "otherwise provide", or whether other sources, such as

the Elements of Crimes, could also provide for a deviation. This debate continued during the

negotiation of the Elements. Some delegations were of the view that the Elements could not call

for a deviation from article 30, as the Elements document is subsidiary to the Statute38. Other

delegations, while conceding that the Elements could not override the Statute, argued that some

deviations were necessary to make the crimes workable and to faithfully reflect the intent of the

Statute as well as the jurisprudence. The latter view was eventually accepted, and the solution

reached appears in the General Introduction to the Elements, paragraph 2: "Exceptions to the

article 30 standard, based on the Statute, including applicable law under its relevant provisions,

are indicated below" (emphasis added). This formulation recognizes the primacy of the Statute,

and indicates that exceptions must directly or indirectly flow from the Statute, but also

recognizes that the Statute itself, through article 21 (applicable law), allows reliance on other

sources, including treaties, general principles and the Elements. Thus, the approach seems to

avoid suggesting that States Parties could legislate a deviation through the Elements, but allows

them to codify a deviation where necessary to reflect their intent when drafting the Statute or to

reflect the relevant treaties and jurisprudence39.

There are various ways in which the Statute, and the elaboration of the Statute contained in

the Elements, provide for departures from the article 30 standard. In almost all cases, the effect

is to reduce the standard that would otherwise apply.

For example, article 28 (a), of the Statute, on command responsibility, requires that a

commander knew "or should have known" of the commission of crimes. The "should have

known" standard reflects the principle that the commander is under a duty to make arrangements

to remain informed of the activities of forces under his or her control. The precise meaning of

"should have known" remains for the Court to determine. As the Statute is a criminal law

instrument, it is unlikely that a mere civil negligence standard is sufficient, but it is clear that the

standard is lower than the article 30 standard. Similarly, article 28 (b), requires that non-military

superiors either knew "or consciously disregarded information which clearly indicated" the

commission of crimes. This standard of culpability is higher than that imposed on the military

commander (as the latter is obliged to maintain a system of military discipline), but still reflects

the principle that anyone commanding forces is subject to some duty.

38 Article 9 para. 3.

39 A subsequent agreement among all treaty parties concerning the application or interpretation of a treaty may

be taken into account in interpreting the treaty: article 31 para. 3 of the VCLT.

856 Donald K. Piragoff/Darryl Robinson

Mental element article 30

Similarly, with the war crime of conscripting or enlisting children under the age of fifteen

years40, the Elements require only that the perpetrator "knew or should have known" that the

person was under the age of fifteen years. This flexible mental element, regarding the age of the

children recruited, reflects the interpretation of delegations that persons recruiting or enlisting

young persons are under some degree of obligation to try to verify the age41. Again, the precise

meaning of "should have known" remains for the Court to determine42.

A reduced mental element is also articulated with respect to each of the "contextual

elements", i.e. the circumstance elements that address the surrounding context that renders a

crime a matter of concern to the international community as a whole43. For war crimes, this is

the existence of an armed conflict; for crimes against humanity, it is the widespread or

systematic attack against a civilian population; and for genocide, it is the pattern of genocidal

conduct44. Since these contextual elements do not relate directly to the conduct of the accused,

but rather to the context creating an international dimension, the full application of article 30

was not considered necessary. At the same time, some degree of awareness of the context was

considered necessary for the perpetrator to be held responsible for an international crime45.

Therefore the Elements provide for a reduced mental element in relation to the contextual

elements46.

Rather than merely reducing the mental element required, a provision may modify the

default rule of article 30 by indicating that no mental element is required at all. For example, for

the crime against humanity of persecution, article 7 para. 1 (h) requires that the persecutory

conduct be committed in connection with any act in article 7 para. 1 or with any ICC crime. This

requirement was inserted to ensure that the Court would deal only with serious cases of criminal

severity. Accordingly, during the Elements debates, the provision was regarded as a

"jurisdictional" provision and not a component of the evil of the crime, so the Elements specify

that a corresponding mental element is not required47.

It is also possible to require an additional element of intent or knowledge; for example, some 15

provisions of the Statute require that the impugned conduct (which must be committed with

intent and knowledge, by virtue of article 30 para. 1) also be committed for a specific or ulterior

purpose; i.e., "with intent to" or "with the intention of" achieving certain ends or purposes48. In

some instances, the Elements of Crimes have added specific intents to further elaborate the

definitional elements contained in the Statute49. These are specific intents or dolus specialis,

40 Article 8 para. 2 (b) (xxvi). The "should have known" standard was also adopted in the elements for article 8

para. 2 (b) (vii) (improper use of flag of truce, etc.)

41 See also the elements for article 6 lit. e, genocide by forcibly transferring children.

42 The term "should have known" is used, for example, in supra note 37, Prosecutor v. Akayesu, Case No.

ICTR-96-4-T, para. 520, where in the context it appears to refer not to a civil negligence standard but rather a

criminal law standard (wilful blindness is one possibility).

43 Article 5 of the Statute.

44 See paragraph 7 of the General Introduction to the Elements, and the final element of each crime.

45 See for example, ICTY cases such as Prosecutor v. Tadic, Case No. IT-91-1-A, Judgment, Appeal Chamber,

15 July 1999, para 255 and national cases such as supra note 26, R. v. Finta [1994], 1 S.C.R. 701, 815 and

819.

46 For genocide, given that knowledge of the genocidal context would inevitably be established in the course of

proving genocidal intent, "the appropriate requirement, if any, for a mental element regarding this

circumstance" was left to be determined by the Court: Elements, Introduction to Genocide. For crimes

against humanity, the Elements clarify that the perpetrator need not have knowledge of the characteristics of

the attack nor of the details of the plan or policy: Elements, Introduction to Crimes Against Humanity. For

war crimes, knowledge of the armed conflict is listed as an element, but the introduction to war crimes limits

the extent of awareness required, leaving the mental requirement highly ambiguous and for the Court to

determine: Elements, Introduction to War Crimes.

47 Elements, fn. 21.

48 E.g., article 6 ("with intent to destroy"); article 7 para. 2 (h) and (i) ("with the intention of maintaining";

"with the intention of removing").

49 E.g., Elements of Crime concerning article 8 para. 2 (b) (xii) ("in order to"), and article 8 para. 2 (a) (ii)-1

("for such purposes as").

Donald K. Piragoff/Darryl Robinson 857

article 30 Part 3. General principles of criminal law

which are required in addition to the general intent that is to be imported by paragraph 1 into the

definition of crimes. The specific intent is an element that must be proved in addition to any

intent imposed by article 30. It is a separate mental element that is not linked to any material

element that must be proved or to which the article 30 would apply. It does not require that that

which is intended to be achieved, actually results in fact. For example, under article 6

(genocide), any of the various acts listed under (a) (e) must be committed intentionally (by

virtue of article 30), with the additional specific intent (i.e., purpose) to destroy a particular

group; it is not necessary to prove that the group was actually destroyed.

Although some early proposals had contemplated making mention of both types of intent50,

the decision of the Preparatory Committee was that "there was no need, however, to distinguish

between general and specific intention, because any specific intent should be included as one of

the elements of the definition of the crime"51. Accordingly, paragraph 1 of article 30 only refers

to "intent". See below, under the discussion of paragraph 2, whether the meaning of the term

"intent", as used in those provisions where a specific intent is required, is to be interpreted in

accord with both or only one of the definitions of "intent" as defined in article 30 para. 2.

Finally, some Statute provisions may appear to modify the article 30 standard but are not

intended to do so. For example, some of the war crimes provisions use terms such as "wilful" or

"wilfully"52, and the term "deliberately" appears in one of the forms of genocide53. These terms

appear because many of the Rome Statute provisions faithfully reproduced definitions in

instruments such as the Geneva Conventions or Genocide Conventions, which were considered

customary international law. It appears that the intent of the drafters was not to deviate from the

default rule of article 30, and this interpretation is now confirmed by the approach in the

Elements54.

II. Paragraph 2

1. "For the purposes of this article"

16 This phrase appears to signify that the definitions in paragraphs 2 and 3 apply directly to

article 30 and apply indirectly to the Statute through the operation of paragraph 1, which imports

"intent" and "knowledge" as the minimum mens rea into all of the crimes within the jurisdiction

of the Court, unless otherwise provided. Therefore, other provisions of the Statute could provide

for different definitions or meanings of these terms in respect of specific crimes. No specific

alternative definitions of these terms, however, are provided in the current Statute.

III. Sub-paragraph 2 (a)

1. "conduct"

17 Commencing with the August 1996 session of the Preparatory Committee55, the Draft

Statute had contained a bracketed proposal concerning "Actus reus" (act and/or omission), which

was further refined at the February 1997 session56 and submitted to the Rome Conference57.

Paragraph 1 of then article 28 had provided that conduct can "constitute either an act or

50 1996 Preparatory Committee II, p. 92.

51 1996 Preparatory Committee I, p. 45, para. 199.

52 Article 8 para. 2 (a) (i) and (iii).

53 Article 6 lit. c.

54 See, e.g., Elements, article 6 lit. d, element 1; article 8 para. 2 (a) (i), element 1; and article 8 para. 2 (a) (iii),

element 1; none of which provide an alternative mental element and therefore rely on article 30.

55 1996 Preparatory Committee I, p. 45 and II, p. 90.

56 Preparatory Committee Decisions Feb. 1997, p. 26.

57 Report of the Preparatory Committee on the Establishment of an International Criminal Court, UN GAOR,

53rd Sess., UN Doc. A/AC.249/1998/CRP. 7 (1998), p. 6465 (article 28).

858 Donald K. Piragoff/Darryl Robinson

Mental element article 30

omission, or a combination thereof". Paragraph 2 of then article 28 attempted to describe the

circumstances in which a person could be held criminally responsible for an omission, which

included some proposed circumstances that implied mental elements other than intent or

knowledge. At the Rome Conference, agreement could not be reached on this proposed article,

and it was decided to delete it from the Statute with the understanding that the question of when,

and if, omissions might constitute or be equivalent to conduct would have to be resolved in

future by the Court.

Therefore, for the purposes of article 30 the term "conduct" denotes positive action and may 18

also include an intentional omission, where the causal result and moral culpability of the

intentional omission is equivalent to the achievement of the same result caused by an intentional

act58. As for the inclusion of any other type of omissions within the Statute (including their

mental elements), these would have to be governed by, or through the Courts interpretation of,

other provisions of the Statute59 through the opening words of paragraph 1 ("Unless otherwise

provided") and in accord with article 21.

2. "means to engage in the conduct"

This phrase signifies, at a minimum, that conduct must be the result of a voluntary action on 19

the part of an accused. It includes the basic consciousness or volition that is necessary to

attribute an action (i.e., actus reus) as being the product of the voluntary will of a person. In this

sense, however, the phrase merely distinguishes involuntary from voluntary conduct. Generally,

the term "intent" also connotes some element, although even minimal, of desire or willingness to

do the action, in light of an awareness of the relevant circumstances or likely consequences. As

noted earlier, unless relevant circumstances are known that qualify the action as prohibited

conduct, it cannot be said that the person intends the conduct. Therefore, "intent" necessarily

includes an element of "knowledge"60. In the civil law, these concepts are incorporated in the

term "dolus directus".

As was noted above ("Material Elements"), where a conduct element involves a legal

conclusion or value judgement, it is not required that the accused correctly completed the legal

or normative evaluation, but simply that the accused was aware of the relevant facts61.

IV. Sub-paragraph 2 (b)

1. "consequence"

Some crimes prohibit conduct62,

other crimes prohibit not only conduct but the consequences 20

that causally occur63 and other crimes prohibit the causing of consequences without specifying a

particular predicate conduct64. Often conduct and consequence can be intertwined with little

distinction in time or place between the two65. In all situations where a consequence is part of

the definition of a crime, paragraph 2 of article 30 defines what is meant when paragraph 1

58 E.g., article 8 para. 2 (b) (xxv) ("intentionally using starvation of individuals..."). The omission of

intentionally starving individuals results in the achievement of the equivalent result (i.e., death) as would an

intentional killing.

59 E.g., article 28 paras. 1 (b) and 2 (c) ("failed to take all necessary and reasonable measures ...").

60 G. Williams, TEXT BOOK OF CRIMINAL LAW 52 (1978), and 116117 (2nd ed. 1983).

61 One example of a conduct element involving a value judgment would be the intentional infliction of "severe"

pain or suffering: article 7 para. 1 (f).

62 E.g., article 8 para. 2 (b) (i) ("directing attacks against civilian objects").

63 E.g., article 7 para. 1 (k) ("Other inhumane acts of a similar character intentionally causing great suffering, or

serious injury to body or to mental or physical health").

64 E.g., article 6 (b) ("causing serious bodily harm or mental harm to members of the group").

65 E.g., article 8 para. 2 (a) (i) ("wilful killing").

Donald K. Piragoff/Darryl Robinson 859

article 30 Part 3. General principles of criminal law

requires that the consequences (where consequences are material elements) be committed with

intent.

As was noted above ("Material Elements"), where a consequence element involves a legal

conclusion or value judgement, it is not required that the accused correctly completed the legal

or normative evaluation, but simply that the accused was aware of the relevant facts66.

2. "means to cause that consequence"

21 This reflects the notion that specified consequences in the definition of a crime must causally

follow from the persons conduct, and that the person desires or means that such consequences

occur. The phrase incorporates both the concepts of a desire for the occurrence of consequences

(i.e., dolus directus) and a causal connection between the person and the consequence.

The observations made above concerning conduct elements involving a "value judgement"

apply equally to consequence elements.

3. "aware that it will occur in the ordinary course of events"

22 Traditionally, in most legal systems, "intent" does not only include the situation where there

is direct desire and knowledge that the consequence will occur or will be caused, but also

situations where there is knowledge or foresight of such a substantial probability that the

consequence will occur. Few things in life are certain, and certainty is often a question of

degree. People generally govern their lives on the basis that common sense or the ordinary

course of events would pronounce that the occurrence of a particular consequence flowing from

a particular conduct is highly probable, such as to be equivalent to certainty for all practical

purposes. This is likely the meaning to be attributed to the phrase "will occur in the ordinary

course of events". In civilian legal systems, it is a notion captured by the concept of dolus

eventualis67. In common law systems, it is generally considered as being a form of intent.

23 During the course of debate over article 6, many delegations expressed concerns that the

phrase "with intent to destroy" needed clarification, particularly with respect to distinguishing

between "responsible decision makers or planners and a general-intent or knowledge

requirement for the actual perpetrators of genocidal acts"68. However, it was emphasised that the

Statute was not the appropriate forum for considering amendments to the Genocide Convention

and that "the question of intent could be addressed under the applicable law or the general

provisions of criminal law"69. The definition of "intent" in paragraph 2, by clearly encompassing

both concepts of intention as described in paragraph 2 (a) and (b), is able to addresses the

concern that the actual perpetrators of genocidal acts, while not specifically intending or

meaning that their acts destroy an entire group, may nonetheless be aware that such consequence

66 One example of a consequence element involving a value judgment would be that the conduct caused death

or "seriously endangered the health" of the victims (article 8 para. 2 (b) (x)).

67 The concept "dolus eventualis" does not have a monolithic or uniform meaning within all civil law systems.

Nevertheless, in all civil law systems, it appears to include the concept connoted by the phrase "will occur in

the ordinary course of events"; i.e., an awareness of a substantial or high degree of probability that the

consequence will occur. However, in some civil law systems, it also includes the situation of an awareness of

a substantial or serious risk that a consequence will occur and indifference whether it does, which is similar

to the concept of "recklessness" in many common law countries. Additionally, some civil law countries may

also consider some mental states of inadvertence to be included in this concept. Due to different national

conceptions, attempts to define the concepts were abandoned during the negotiations. Whatever may be the

merits of the distinction under national legal systems, it was clear that the first-noted meaning of "dolus

eventualis" is included (i.e., "will occur in the ordinary course of events"). The latter meanings of "dolus

eventualis" or "recklessness" were not incorporated explicitly into article 30, although it may be open to the

Court to interpret the inclusion of some aspects of these meanings, which import a high degree of advertence

or probability. The concepts may also exist in some specific crimes in the Statute under a different name

(e.g., article 28). See supra note 5, P. Saland, 205; and supra note 5, R. S. Clark, 301, 314315.

68 Ad Hoc Committee Report, p. 13, para. 62; 1996 Preparatory Committee I, p. 17, para. 60.

69 1996 Preparatory Committee I, p. 17, para. 60.

860 Donald K. Piragoff/Darryl Robinson

Mental element article 30

will occur in the ordinarily course of events as a result of their acts. Alternatively, it can also be

argued that the specific intent referred to in article 6 connotes a more limited meaning of

"intent", such as is described only in paragraph 2 (a) of article 30, which is preserved by the

opening words of paragraph 1 ("Unless otherwise provided")70. It will be for the Court to

interpret the meaning of "intent" in article 6 in light of its historical antecedents and the effect of

article 30 and the Elements of Crimes.

V. Paragraph 3

1. "For the purposes of this article"

See discussion of the same phrase in paragraph 2, above. 24

2. "awareness that a circumstance exists"

See the discussion of "knowledge" under paragraph 1 and paragraph 2 (a), above. Awareness 25

or consciousness of the existence of relevant circumstances that define or qualify a crime

connotes the common understanding of "knowledge" or the concept that a crime be committed

"knowingly". It is a concept that is significantly intertwined with the meaning of "intent", as

discussed earlier.

Awareness of a circumstance is a question of degree, and some legal systems include within 26

this concept the state of mind where a person greatly suspects the true state of affairs but

deliberately avoids steps to ascertain their validity or deliberately shuts his or her eyes to an

obvious means of knowledge. This is often referred to as "wilful blindness", which is

tantamount to actual knowledge71. It is distinguished from "recklessness" or even "negligence"

due to the conscious awareness of the substantial risk of the true state of affairs and the

deliberate avoidance of taking steps to find out the truth. Essentially, the person does not want to

know and deliberately shuts his or her eyes to the truth. It may be argued that the specific

definition in paragraph 3 excludes such concept and that actual awareness or cognizance is

required. Alternatively, it may also be open to the Court to interpret "awareness" to include

wilful blindness in some situations.

An erroneous appreciation or awareness of the relevant facts by an accused can constitute a 27

defence of mistake of fact, as such mistake is a negation of the requisite "knowledge" or

awareness of relevant circumstances. This is specifically acknowledged in article 32 para. 1.

As was noted above ("Material Elements"), where a circumstance element involves a legal

conclusion or value judgement, it is not required that the accused correctly completed the legal

or normative evaluation, but simply that the accused was aware of the relevant facts72.

3. "awareness that...a consequence will occur in the ordinary course of events"

See discussion of the same concept of "awareness" under article 30 para. 2 (b), discussed 28

above under the heading of "Awareness that a circumstance exits".

70 The more restrictive meaning was given to the phrase "with intent to destroy" by the ICTR in supra note 37,

Prosecutor v. Akayesu, Case No. ICTR-96-4-T. Subsequent cases have also indicated a fairly onerous mens

rea requirement (specific intent or dolus eventualis) and that the accused must share in this intent: Prosecutor

v. Rutaganda, ICTR-96-3-T, Judgment, Trial Chamber, 6 Dec. 1999, para 5962; Prosecutor v. Jelisic, IT-

95-10-T, Judgment, Trial Chamber, 14 Dec. 1999, para 78; Prosecutor v. Krstic, Case No. IT-98-33-T,

Judgment, Trial Chamber, 2 Aug. 2001.

71 E.g., see J.C. Smith/B. Hogan, CRIMINAL LAW 103 (4th ed. 1978).

72 One example of a circumstance element involving a value judgment would be that the conduct "was of a

character similar" to other acts listed in article 7 para. 1 (article 7 para. 1 (k)).

Donald K. Piragoff/Darryl Robinson 861

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Benchmemov2 01Document64 pagesBenchmemov2 01Srijana RegmiNo ratings yet

- Benchmemov2 01Document64 pagesBenchmemov2 01Srijana RegmiNo ratings yet

- Benchmemov2 01Document64 pagesBenchmemov2 01Srijana RegmiNo ratings yet

- (Exemplar) The Secret River Coursework Essay 3Document3 pages(Exemplar) The Secret River Coursework Essay 3Andrei PrunilaNo ratings yet

- Domestic Incident Report FormDocument7 pagesDomestic Incident Report FormZez SamuelNo ratings yet

- Creating Public Value in Complex and Changing TimesDocument45 pagesCreating Public Value in Complex and Changing TimesFelipe100% (2)

- Companies Act 2013 IndiaDocument15 pagesCompanies Act 2013 IndiaBhagirath Ashiya100% (2)

- The Essence of Neoliberalism - Le Monde Diplomatique - English EditionDocument3 pagesThe Essence of Neoliberalism - Le Monde Diplomatique - English EditionMA G. D Abreu.100% (1)

- 21 - G.R.No.195021 - Velasquez V People - MSulit - March 21Document2 pages21 - G.R.No.195021 - Velasquez V People - MSulit - March 21Michelle Sulit0% (1)

- 15th IHL Moot - Moot Problem - FINAL PDFDocument11 pages15th IHL Moot - Moot Problem - FINAL PDFSrijana RegmiNo ratings yet

- 459ADocument65 pages459ASrijana RegmiNo ratings yet

- Dat. 028 NEUDocument49 pagesDat. 028 NEUSrijana RegmiNo ratings yet

- Bibliography TemplateDocument1 pageBibliography TemplateSrijana RegmiNo ratings yet

- 2013 ApplicantDocument54 pages2013 ApplicantSrijana RegmiNo ratings yet

- Memorial, NepalDocument36 pagesMemorial, NepalSrijana RegmiNo ratings yet

- Memorial, NepalDocument36 pagesMemorial, NepalSrijana RegmiNo ratings yet

- Human Trafficking and Transportation (Control) Act, 2064: Short Title, Extension and CommencementDocument12 pagesHuman Trafficking and Transportation (Control) Act, 2064: Short Title, Extension and CommencementSrijana RegmiNo ratings yet

- Ga Resolution 2625Document9 pagesGa Resolution 2625Srijana RegmiNo ratings yet

- Convention On TortureDocument24 pagesConvention On TortureSrijana Regmi100% (1)

- Secretary's Certificate SampleDocument1 pageSecretary's Certificate SampleSeth InfanteNo ratings yet

- Harborco: Iacm Conference, Bonn, 1997Document3 pagesHarborco: Iacm Conference, Bonn, 1997muralidarinNo ratings yet

- Odigo Warns Israelis of 9-11 Attack (From Haaretz) - My Related Article at Http://tinyurl - Com/8b5kvx6Document3 pagesOdigo Warns Israelis of 9-11 Attack (From Haaretz) - My Related Article at Http://tinyurl - Com/8b5kvx6alibaba1aNo ratings yet

- Access SBM Pasbe FrameworkDocument46 pagesAccess SBM Pasbe FrameworkRoland Campos100% (1)

- Normal Chaos of Family Law Dewar MLR 1998Document19 pagesNormal Chaos of Family Law Dewar MLR 1998CrystalWuNo ratings yet

- Aristotle (384 - 322 BCE)Document22 pagesAristotle (384 - 322 BCE)tekula akhilNo ratings yet

- Rise of Political Islam and Arab SpringDocument21 pagesRise of Political Islam and Arab Springwiqar aliNo ratings yet

- Umair Hamid - Court TranscriptDocument28 pagesUmair Hamid - Court TranscriptDawn.com100% (1)

- Poa Cri 173 Comparative Models in Policing 1Document10 pagesPoa Cri 173 Comparative Models in Policing 1Karen Angel AbaoNo ratings yet

- Synthesis of Studying CultureDocument3 pagesSynthesis of Studying CultureAl Cheeno AnonuevoNo ratings yet

- WebinarDocument42 pagesWebinarMAHANTESH GNo ratings yet

- The Cuban Revolution EssayDocument4 pagesThe Cuban Revolution EssayJulian Woods100% (6)

- GAD Plan and Budget TemplateDocument2 pagesGAD Plan and Budget TemplateMelanie Delos SantosNo ratings yet

- ABC Diplomacy enDocument40 pagesABC Diplomacy envalmiirNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 881 August 30, 1902 THE UNITED STATES, Complainant-Appellee, vs. PEDRO ALVAREZ, Defendant-AppellantDocument3 pagesG.R. No. 881 August 30, 1902 THE UNITED STATES, Complainant-Appellee, vs. PEDRO ALVAREZ, Defendant-AppellantRache BaodNo ratings yet

- Second Quarter Examination: Politics and Governance ReviewDocument8 pagesSecond Quarter Examination: Politics and Governance ReviewRomeo Erese IIINo ratings yet

- Manila Lawn Tennis Club lease dispute resolved by Supreme CourtDocument1 pageManila Lawn Tennis Club lease dispute resolved by Supreme CourtShimi FortunaNo ratings yet

- Viking PresentationDocument95 pagesViking PresentationStuff Newsroom100% (1)

- Eugene Dupree v. United States, 264 F.2d 140, 3rd Cir. (1959)Document7 pagesEugene Dupree v. United States, 264 F.2d 140, 3rd Cir. (1959)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Book - Ethiopian Yearbook of International LawDocument283 pagesBook - Ethiopian Yearbook of International LawTesfaye Mekonen100% (1)

- Answer With Counterclaim and Cross ClaimDocument10 pagesAnswer With Counterclaim and Cross ClaimRedbert Dela CernaNo ratings yet

- Lanuevo Disbarred for Unauthorized Reevaluation of Bar Exam ResultsDocument1 pageLanuevo Disbarred for Unauthorized Reevaluation of Bar Exam ResultsLgie LMNo ratings yet

- 407) Macalintal vs. COMELEC (G.R. No. 157013, July 10, 2003)Document185 pages407) Macalintal vs. COMELEC (G.R. No. 157013, July 10, 2003)Carmel Grace KiwasNo ratings yet

- Ong Chiu Kwan v. CADocument2 pagesOng Chiu Kwan v. CALouise QueridoNo ratings yet