Professional Documents

Culture Documents

00423

Uploaded by

Thiago SartiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

00423

Uploaded by

Thiago SartiCopyright:

Available Formats

This online-rst version will be replaced with a nal version when it is included in the issue.

The nal version may differ in small ways.

Annals of Internal Medicine POSITION PAPER

Policy Recommendations to Guide the Use of Telemedicine in Primary

Care Settings: An American College of Physicians Position Paper

Hilary Daniel, BS, and Lois Snyder Sulmasy, JD, for the ACP Health and Public Policy Committee*

Telemedicinethe use of technology to deliver care at a mary care and reimbursement policies associated with telemedi-

distanceis rapidly growing and can potentially expand access cine use. The positions put forward by the American College of

for patients, enhance patientphysician collaboration, improve Physicians highlight a meaningful approach to telemedicine pol-

health outcomes, and reduce medical costs. However, the po- icies and regulations that will have lasting positive effect for pa-

tential benets of telemedicine must be measured against the tients and physicians.

risks and challenges associated with its use, including the ab-

sence of the physical examination, variation in state practice and

licensing regulations, and issues surrounding the establishment

of the patientphysician relationship. This paper offers policy rec- Ann Intern Med. doi:10.7326/M15-0498 www.annals.org

ommendations for the practice and use of telemedicine in pri- For author afliations, see end of text.

T he use of telemedicine (use of technology to deliver

health care services at a distance) and telehealth

services (a somewhat broader denition of telemedi-

for each is provided in the full position paper (see the

Appendix, available at www.annals.org).

In 2008, ACP published a position paper, E-Health

cine that includes not just delivery of health care ser- and Its Impact on Medical Practice (2), which discussed

vices at a distance but patient and health professional how the use of technology (including electronic health

education, public health, and public administration [1]) records, patient portals, and telemedicine) can aug-

has expanded rapidly to solidify a place in the modern ment the practice of medicine in an efcient and secure

health care conversation. The use of telemedicine tech- way. Since that paper's releasejust 1 year after the rst

nologies began mainly in rural communities and fed- iPhone (Apple) was introducedthe use of technology

eral health programs but has since been used in vari- is engrained into the everyday lives of persons across

ous medical specialties and subspecialties across care the United States and the world. The use of these tech-

settings. The term telemedicine comprises different nologies has been shown to increase patient satisfac-

types of technologies with different applicable func- tion while delivering care that is similar in quality to,

tions, outlined in the Table. and in some cases more efcient than, in-person care

Although telemedicine has been a component of and support. Research shows that telemedicine can po-

the health care eld for decades, only since the broad tentially reduce costs, improve health outcomes, and

proliferation of computer and smartphone technology increase access to primary and specialty care.

into the everyday lives of the general population has

telemedicine taken a foothold in how health care may

be delivered to larger groups of patients. Telemedicine METHODS

holds the promise to improve access to care, improve The ACP's Health and Public Policy Committee,

patient satisfaction, and reduce costs to the health care which is charged with addressing issues affecting the

system. However, various challenges and risks of tele- health care of the U.S. public and the practice of inter-

medicine, such as variations in state and federal laws, nal medicine and its subspecialties, developed these

limited reimbursement, logistic issues, and concerns positions and recommendations. The committee re-

about the quality and security of the care provided, viewed studies, reports, and surveys on all applications

should not be overlooked. and uses of telemedicine, patient satisfaction with tele-

As telemedicine technologies and applications medicine, and quality of telemedicine in addition to the

continue to develop and evolve, the American College legal landscape surrounding telemedicine, including li-

of Physicians (ACP) has compiled pragmatic recom- censing, prescribing, credentialing, and other legal re-

mendations on the use of telemedicine in the primary quirements. Draft recommendations were reviewed by

care setting, physician considerations for those who

use telemedicine in their practices, and policy recom-

mendations on the practice and reimbursement of tele- See also:

medicine. The statements represent the ofcial policy Editorial comment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

positions and recommendations of ACP. The rationale

* This paper, written by Hilary Daniel, BS, and Lois Snyder Sulmasy, JD, was developed for the Health and Public Policy Committee of the American College

of Physicians (ACP). Individuals who served on the Health and Public Policy Committee at the time of the project's approval and authored this position paper

were Thomas Tape, MD (Chair); Douglas M. DeLong, MD (Vice-Chair); Micah W. Beachy, DO; Sue S. Bornstein, MD; James F. Bush, MD; Tracey Henry, MD;

Gregory A. Hood, MD; Gregory C. Kane, MD; Robert H. Lohr, MD; Ashley Minaei; Darilyn V. Moyer, MD; Kenneth E. Olive, MD; and Shakib Rehman, MD.

Approved by the ACP Board of Regents on 27 April 2015.

This article was published online rst at www.annals.org on 8 September 2015.

www.annals.org Annals of Internal Medicine 1

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ on 09/15/2015

This online-rst version will be replaced with a nal version when it is included in the issue. The nal version may differ in small ways.

POSITION PAPER Recommendations for the Use of Telemedicine in Primary Care Settings

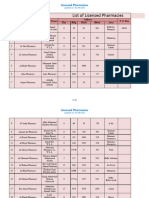

Table. Types of Telemedicine

Type of Telemedicine Description Example

Asynchronous Transmits a patient's medical information The radiographs of a patient's broken wrist are sent off site to an orthopedist for

not used in real time* evaluation as to whether the patient needs surgery

Synchronous Real-time interactive technologies, such as A physician sets aside 2 h each weeknight for e-visits in which patients can

2-way interactive video connect with the physician through a Webcam and be "seen" for acute health

conditions from their homes

A rural community with no primary care physicians connects patients at a

community health center through a 2-way video with physicians at a remote

location

Remote patient A patient's health information is gathered A patient with hypertension changes medication and uses a monitoring device

monitoring through technological devices and sent to measure blood pressure over the course of a week. The information is

for evaluation and stored in the patient's transferred to the patient's physician, who determines whether the patient

medical record for future use needs to come to the ofce for follow-up

Mobile health care Uses mobile technology, such as A primary care practice uses text messages to conrm appointments with

services smartphone applications and text patients

messages, to manage and track health

conditions or promote healthy behaviors

* Store and forward.

ACP's Board of Regents, Board of Governors, Council 3. ACP recommends that telehealth activities ad-

of Early Career Physicians, Council of Resident/Fellow dress the needs of all patients without disenfranchising

Members, Council of Student Members, and Council of nancially disadvantaged populations or those with low

Subspecialty Societies. The position paper and recom- literacy or low technologic literacy. In particular, tele-

mendations were reviewed by the ACP Board of health activities need to consider the following:

Regents. a. The literacy level of all materials (including writ-

ten, printed, and spoken words) provided to patients or

ACP POSITION STATEMENTS AND families.

b. Affordability and availability of hardware and In-

RECOMMENDATIONS ternet access.

1. ACP supports the expanded role of telemedicine c. Ease of use, which includes accessible interface

as a method of health care delivery that may enhance design and language.

patientphysician collaborations, improve health out- 4. ACP supports the ongoing commitment of fed-

comes, increase access to care and members of a pa- eral funds to support the broadband infrastructure

tient's health care team, and reduce medical costs needed to support telehealth activities.

when used as a component of a patient's longitudinal 5. ACP believes that physicians should use their

care. professional judgment about whether the use of tele-

a. ACP believes that telemedicine can be most ef-

medicine is appropriate for a patient. Physicians should

cient and benecial between a patient and physician

not compromise their ethical obligation to deliver clin-

with an established, ongoing relationship.

ically appropriate care for the sake of new technology

b. ACP believes that telemedicine is a reasonable

adoption.

alternative for patients who lack regular access to rele-

a. If an in-person physical examination or other di-

vant medical expertise in their geographic area.

c. ACP believes that episodic, direct-to-patient tele- rect face-to-face encounter is essential to privacy or

medicine services should be used only as an intermit- maintaining the continuity of care between the patient's

tent alternative to a patient's primary care physician physician or medical home, telemedicine may not be

when necessary to meet the patient's immediate acute appropriate.

care needs. 6. ACP recommends that physicians ensure that

2. ACP believes that a valid patientphysician rela- their use of telemedicine is secure and compliant with

tionship must be established for a professionally federal and state security and privacy regulations.

responsible telemedicine service to take place. A tele- 7. ACP recommends that telemedicine be held to

medicine encounter itself can establish a patient the same standards of practice as if the physician were

physician relationship through real-time audiovisual seeing the patient in person.

technology. A physician using telemedicine who has no a. ACP believes that there is a need to develop

direct previous contact or existing relationship with a evidence-based guidelines and clinical guidance for

patient must do the following: physicians and other clinicians on appropriate use of

a. Take appropriate steps to establish a relation- telemedicine to improve patient outcomes.

ship based on the standard of care required for an in- 8. ACP recommends that physicians who use tele-

person visit, or medicine should be proactive in protecting themselves

b. Consult with another physician who does have a against liabilities and ensure that their medical

relationship with the patient and oversees his or her liability coverage includes provision of telemedicine

care. services.

2 Annals of Internal Medicine www.annals.org

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ on 09/15/2015

This online-rst version will be replaced with a nal version when it is included in the issue. The nal version may differ in small ways.

Recommendations for the Use of Telemedicine in Primary Care Settings POSITION PAPER

9. ACP supports the ongoing commitment of fed- as policymakers and stakeholders shape the landscape

eral funds to establish an evidence base on the safety, for telemedicine going forward, to balance the benets

efcacy, and cost of telemedicine technologies. of telemedicine against the risks for patients. By estab-

10. ACP supports a streamlined process to obtain- lishing a balanced and thoughtful framework for the

ing several medical licenses that would facilitate the practice, use, and reimbursement of telemedicine in

ability of physicians and other clinicians to provide tele- primary care, patients, physicians, and the health care

medicine services across state lines while allowing system will realize the full potential of telemedicine.

states to retain individual licensing and regulatory

authority. From American College of Physicians, Washington, DC, and

11. ACP supports the ability of hospitals and critical Philadelphia, PA.

access hospitals to privilege by proxy in accordance

with the 2011 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Ser- Financial Support: Financial support for the development of

vices nal rule allowing a hospital receiving telemedi- this guideline comes exclusively from the ACP operating

cine services (distant site) to rely on information from budget.

hospitals facilitating telemedicine services (originating

site) in providing medical credentialing and privileging Disclosures: Authors have disclosed no conicts of interest.

to medical professionals providing those services. Authors followed the policy regarding conicts of interest de-

12. ACP supports lifting geographic site restrictions scribed at www.annals.org/article.aspx?articleid=745942.

Forms can be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors/icmje

that limit reimbursement of telemedicine and tele-

/ConictOfInterestForms.do?msNum=M15-0498.

health services by Medicare to those that originate out-

side of metropolitan statistical areas or for patients who

Requests for Single Reprints: Hilary Daniel, BS, American Col-

live in or receive service in health professional shortage

lege of Physicians, 25 Massachusetts Avenue Northwest, Suite

areas. 700, Washington, DC 20001; e-mail, hdaniel@acponline.org.

13. ACP supports reimbursement for appropriately

structured telemedicine communications, whether syn- Current author addresses and author contributions are avail-

chronous or asynchronous and whether solely text- able at www.annals.org.

based or supplemented with voice, video, or device

feeds in public and private health plans, because this

form of communication may be a clinically appropriate

service similar to a face-to-face encounter.

References

1. Health Resources and Services Administration. Telehealth. Ac-

cessed at www.hrsa.gov/ruralhealth/about/telehealth on 18 June

SUMMARY 2015.

2. American College of Physicians. E-Health and Its Impact on Med-

ACP believes that telemedicine can potentially be a ical Practice. Philadelphia: American College of Physicians; 2008: Po-

benecial and important part of the future of health sition Paper. Accessed at www.acponline.org/advocacy/current

care delivery. However, it is also important, especially _policy_papers/assets/ehealth.pdf on 11 August 2015.

www.annals.org Annals of Internal Medicine 3

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ on 09/15/2015

This online-rst version will be replaced with a nal version when it is included in the issue. The nal version may differ in small ways.

Current Author Addresses: Ms. Daniel: American College of medicine in these specialties and subspecialties, the

Physicians, 25 Massachusetts Avenue Northwest, Suite 700, positions and recommendations put forward by ACP

Washington, DC 20001.

are above all intended for the use of telemedicine in

Ms. Snyder Sulmasy: American College of Physicians, 190 N.

Independence Mall West, Philadelphia, PA 19160. primary care. Specialists and subspecialists provide in-

tegral services and work in conjunction with a patient's

Author Contributions: Conception and design: H. Daniel, primary care physician to provide coordinated care for

D.M. DeLong, M.W. Beachy, G.A. Hood, G.C. Kane, A. Minaei. the patient. ACP recognizes that the application and

Analysis and interpretation of the data: J.F. Bush, A. Minaei. principles for the use of telemedicine for specialties

Drafting of the article: L. Snyder Sulmasy. and subspecialties can vary depending on the situation,

Critical revision of the article for important intellectual con-

care setting, or standard of care.

tent: H. Daniel, L. Snyder Sulmasy, T. Tape, D.M. DeLong,

M.W. Beachy, T. Henry, G.A. Hood, R.H. Lohr, A. Minaei, D.V. Although still emerging, mHealth should also be

Moyer, S. Rehman. considered during telemedicine policy discussions.

Final approval of the article: H. Daniel, L. Snyder Sulmasy, T. Mobile technology use is high and continues to grow:

Tape, D.M. DeLong, M.W. Beachy, S.S. Bornstein, J.F. Bush, T. 90% of U.S. adults have a mobile phone, 58% of whom

Henry, G.A. Hood, G.C. Kane, R.H. Lohr, A. Minaei, D.V. have a smartphone (7). Although less conventionally

Moyer, K.E. Olive, S. Rehman.

Administrative, technical, or logistic support: S.S. Bornstein.

developed or researched than other telehealth ser-

vices, mHealth has positioned itself as a component of

the telemedicine eld. In 2013, the U.S. Food and Drug

Administration issued Mobile Medical Applications:

Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administra-

APPENDIX: EXPANDED BACKGROUND AND tion Staff (8), which explained how the agency plans to

RATIONALE monitor mHealth applications functioning as medical

In the past 10 years, the swift adoption of computer devices that may pose a greater risk to consumers if

and smartphone technology has spurred an interest in they do not fully understand the capabilities or limita-

and use of telemedicine. Telemedicine, as dened by tions of the application.

the Institute of Medicine, is the use of electronic infor- In addition to consumers, physicians, third-party

mation and communications technologies to provide payers, and major companies, federal legislators have

and support health care when distance separates par- taken an interest in the potential of telemedicine to im-

ticipants (3). Telemedicine is often used interchange- prove the system of health care delivery. Dozens of bi-

ably with the term telehealth, which is more broadly partisan bills were introduced during the 113th Con-

dened as the use of technology in general health gress related to telemedicine and health information

related services. Telemedicine may be characterized in technology, including the Telemedicine for Medicare

the public and private sectors differently, with 26 fed- Act (H.R. 3077), which would allow a physician to treat

eral agencies using 7 unique denitions of telemedi- Medicare beneciaries across state lines without ob-

cine and state legislatures determining which denition taining several medical licenses; the Telehealth Mod-

of telemedicine those operating within that jurisdiction ernization Act (H.R. 3750), which would create a single

use for the purposes of practice or reimbursement (4). federal standard for telemedicine use in national health

For the purpose of this document, telemedicine and care programs; the Telehealth Enhancement Act (H.R.

telehealth will be used interchangeably because tele-

3360), which would expand the types of originating

medicine is a component of telehealth activities.

sites under Medicare and Medicaid for the purpose of

Telemedicine comprises asynchronous, synchro-

telemedicine reimbursement; and the Medicare Tele-

nous, remote monitoring, and mobile health care ser-

health Parity Act (H.R. 5380), which would strategically

vice (mHealth) technologies. Denitions and examples

expand Medicare reimbursement for telehealth ser-

of these technologies are found in the Table. A recent

survey of physicians and hospital systems showed that vices administered in urban areas, retail health clinics,

a 2-way video or Webcam was the most commonly and a patient's home and identies additional health

used telemedicine technology (57.8%) and the type of care service professionals that can be reimbursed for

technology in which physicians and hospitals would providing telehealth services. These bills, or bills with

most likely invest (67.1%) (5). Primary care and subspe- similar intent, may be introduced in future Congresses.

cialist referral services, medical education, and con- The scope of many of these bills has broad implications

sumer medical and health information are also com- on the future of telemedicine use. It is critical at this

mon uses of telemedicine (6). Although this paper junction that any federal legislation balances the bene-

references the use of telemedicine for subspecialists ts and risks of telemedicine on the population, the

and other medical specialists, its ability to increase ac- effect on federal health care programs, and the long-

cess to these health professionals, or research on tele- term use of telemedicine.

www.annals.org Annals of Internal Medicine

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ on 09/15/2015

This online-rst version will be replaced with a nal version when it is included in the issue. The nal version may differ in small ways.

Benets of Telemedicine Benets from the use of telemedicine in subspe-

Telemedicine can be an efcient, cost-effective al- cialties are also seen in telestroke services. The Mayo

ternative to traditional health care delivery that in- Clinic telestroke program uses a hub-and-spoke sys-

creases the patient's overall quality of life and satisfac- tem that allows stroke patients to remain in their home

tion with their health care. Data estimates on the communities, considered a spoke site, while a team

growth of telemedicine suggest a considerable in- of physicians, neurologists, and health professionals

crease in use over the next decade, increasing from consult from a larger medical center that serves as the

approximately 350 000 to 7 million by 2018 (9). Re- hub site (17). A study on this program found that a

search analysis also shows that the global telemedicine patient treated in a telestroke network, consisting of 1

market is expected to grow at an annual rate of 18.5% hub hospital and 7 spoke hospitals, reduced costs by

between 2012 and 2018 (10). A study by Lee and col- $1436 and gained 0.02 years of quality-adjusted life-

leagues (11) found that by the end of 2014, an esti- years over a lifetime compared with a patient receiving

mated 100 million e-visits across the world will result in care at a rural community hospital (18). A study funded

as much as $5 billion in savings for the health care sys- by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute is

tem. As many as three quarters of those visits could be enrolling patients with Parkinson disease to measure

from North American patients (11). their ability to connect with neurologists through tele-

Telehealth technologies have long been devel- medicine. Research shows that although these patients

oped and used by government agencies, and the Vet- do better under the treatment of a neurologist, fewer

eran's Health Administration (VHA) has piloted and in- than one half of Medicare patients with the disease see

stituted telehealth programs with measurable positive a neurologist due to lack of access (19). The Patient-

health outcomes. Telemedicine has been used for over Centered Outcomes Research Institute study will test

a decade by Veterans Affairs; in scal year 2013, more the feasibility of patients being treated in their homes,

than 600 000 veterans received nearly 1.8 million epi- whether telemedicine reduces caregiver burden, and

sodes of remote care from 150 VHA medical centers whether it improves the quality of care and overall pa-

and 750 outpatient clinics (12). It has been suggested tient satisfaction (20).

that the VHA could be a potential model for the use of

telehealth in the primary care setting given the agen-

cy's success in providing home telehealth services, Health Outcomes

such as regular contact with a nurse or other members Sample studies of telemedicine used in the treat-

of a patient's medical team to help control chronic con- ment of medical conditions and in various settings sug-

ditions (including diabetes, depression, or hyperten- gest that efcient use of telemedicine technologies can

sion) (13). The VHA's Care Coordination/Home Tele- improve overall health outcomes. Telemedicine as a

health program, with the purpose of coordinating care case-management tool has been shown to improve

of veteran patients with chronic conditions, grew outcomes in older patients with diabetes with limited

1500% over 4 years and saw a 25% reduction in the access to care (21) and in patients with other chronic

number of bed days, a 19% reduction in numbers of conditions (22). An analysis of patient satisfaction with

hospital readmissions, and a patient mean satisfaction physicians during telemedicine encounters found little

score of 86% (14). difference between encounters in the in-person or vir-

The Indian Health Service has also successfully in- tual setting (23).

tegrated telemedicine technology into its infrastruc- Two large-scale telemedicine pilot programs are

ture, and tribal communities across the country and in often referenced as examples of how telemedicine may

remote or rural areas have had increasing access to improve health outcomes. The Antenatal and Neonatal

primary and specialty care through telemedicine. A Guidelines, Education and Learning System program at

comparison study of patients waiting for an evaluation the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences used

by an ear, nose, and throat subspecialist before and telemedicine technologies to provide rural women with

after the introduction of telemedicine in an Alaskan high-risk pregnancies access to physicians and subspe-

community saw signicant decreases in the number of cialists at the University of Arkansas. In addition, the

new patients waiting 5 months or longer for a consul- program operated a call center 24 hours a day to an-

tation (47% before vs. 8% after) and the average wait swer questions or help coordinate care for these

time for an appointment (4.2 vs. 2.9 months) (15). The women and created evidence-based guidelines on

program used store-and-forward technology to take common issues that arise during high-risk pregnancies.

photographs and videos at an originating site in the The program is widely considered to be successful and

community that were then sent to a distant site for eval- has reduced infant mortality rates in the state (24).

uation by subspecialists. This allowed subspecialists to The Extension for Community Healthcare Out-

see the problem and triage patients accordingly, re- comes program focuses on using technology to con-

sulting in reduced wait times and higher efciency (16). nect subspecialists at an academic medical center to

Annals of Internal Medicine www.annals.org

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ on 09/15/2015

This online-rst version will be replaced with a nal version when it is included in the issue. The nal version may differ in small ways.

primary care physicians who are then trained on how to Research suggests that the most cost-effective uses

care for patients with hepatitis C who did not previously of telemedicine are in radiology, home health care,

receive treatment in their communities. The program psychiatry, and prisoner health care but less so in other

found similar health outcomes for the community- applications due to lack of reimbursement by payers

treated group compared with the group that was (29). An analysis of the Health Buddy Program, which

treated in person at the academic medical center (25). used a personalized hand-held device to identify the

In an analysis of the primary care clinicians who partic- need for care management interventions for chronically

ipated in the program, 75% indicated that they had dis- ill Medicare beneciaries, found spending reductions

cussed what they learned through the program with between $312 and $524 per person per quarter (30).

colleagues, spreading information that can potentially The overall cost savings associated with telemedicine

help others in treating liver diseases (26). may not be seen immediately, but over time. As the use

of telemedicine increases, additional analysis of the

cost-effectiveness or cost benet comparison of tele-

Access

medicine against in-person visits will be needed to fully

One of the broadest benets of telemedicine is in-

understand the scope of potential savings to the health

creased access to primary and specialty care for pa-

care system.

tients to physicians and subspecialists, physicians to

potential patients, hospitals to patients, and physicians Challenges of Telemedicine

to other physicians. Telemedicine technologies can The integration of telemedicine into the health care

connect patients with a clinician without having to incur system is not without challenges. Most laws and regu-

long travel times and associated expenses if they do lations relating to reimbursement and the practice of

not have ready access or are unwilling to travel. An medicine were drafted before the use of telemedicine

analysis of cost savings during a telehealth project at by larger markets; state guidelines on the practice of

the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences be- telemedicine, prescribing, and licensing vary; Web

tween 1998 and 2002 suggested that 94% of partici- sites that offer on-demand, episodic care for minor

pants would have to travel more than 70 miles for med- health conditions may disrupt the continuity of care be-

ical care (27). Elsewhere, hospitals, academic medical tween a patient and his or her physician or medical

centers, physician ofces, and clinics may be linked home and undermine care coordination; and some

through mobile workstations that can connect medical hesitation remains among physicians and patients. Le-

professionals in each location with a large network of gal barriers to the widespread adoption of telemedi-

off-site physicians and subspecialists. cine mainly center on medical licensure, credentialing,

Beyond the rural setting, telemedicine may aid in and privileging that would allow physicians to practice

facilitating care for underserved patients in both rural in several locations. Beyond these challenges, concerns

and urban settings. Two thirds of the patients who par- exist about depersonalization of the patientphysician

ticipated in the Extension for Community Healthcare relationship, particularly in the primary care setting,

Outcomes program were part of minority groups, sug- and the risk for harm. The physical interaction between

gesting that telemedicine could be benecial in help- a physician and patient and the in-person examina-

ing underserved patients connect with subspecialists tion are important components of a patient's care that

they would not have had access to before, either allow a physician to gather a comprehensive under-

through direct connections or training for primary care standing of the patient and his or her needs and build

physicians in their communities, regardless of geo- trust and communication.

graphic location.

Licensing

Cost Current law requires physicians to be licensed in

Treating patients at home or outside the clinical the jurisdiction in which a patient receives treatment,

setting, when applicable and appropriate, can yield with some limited exceptions, and a relatively small

cost savings by intervening before the development of number of physicians have more than 3 active medical

more serious conditions, reducing hospital visits or re- licenses (6%) (31). Most proposals to change the med-

admissions, effectively managing chronic conditions, ical licensing system fall into the categories of preemp-

and reducing travel costs or lost productivity. A pro- tion, mutual recognition and portability, or federal li-

gram in New Mexico that used telemedicine to provide censure and regulation. State medical licensing policy

hospital-level care in a patient's home found savings of and how it relates to telemedicine varies, and many

19% over similar patients who were treated in the hos- states have exceptions that allow a physician to consult

pital setting, mostly derived from shorter length of stay with a physician licensed in another state. However,

in the hospital and fewer diagnostic and laboratory consultation exemptions are not consistent, and some

tests (28). states do not have explicit exemptions (3). Other states

www.annals.org Annals of Internal Medicine

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ on 09/15/2015

This online-rst version will be replaced with a nal version when it is included in the issue. The nal version may differ in small ways.

have specialty licenses allowing physicians to practice Direct-to-Patient Episodic Telemedicine

across state lines for telemedicine only, special pur- As the use of telemedicine has grown in the physi-

pose licenses, or telemedicine licenses or certicates cian and patient populations, the term telemedicine

(32). In 2014, the Federation of State Medical Boards has increasingly become synonymous with Web sites or

(FSMB) nalized an interstate compact that would help mobile health applications that provide episodic care

expedite the licensing process for physicians in obtain- for low-acuity health conditions. Depending on state

ing medical licenses in several states. The compact law, these services enable patients and physicians to

would allow physicians who meet eligibility require- interact 24 hours a day via 2-way video conferencing on

ments to apply for an expedited medical license in a a computer, smartphone, tablet, or telephone. They

principal state, complete necessary registration estab- also allow physicians to diagnose acute conditions;

lished by an Interstate Commission, and receive a li- prescribe drugs; offer medical advice or second opin-

cense in a member state. The physician must pay asso- ions; and refer patients to a different physician, subspe-

ciated fees required by the states and the Interstate cialist, or more appropriate treatment location (such as

an urgent care center or emergency department). This

Commission.

type of consumer-driven health care poses challenges

to maintaining a patient-centered, longitudinal relation-

ship between a patient and his or her physician.

Variation of State Regulation Patient preference is increasingly driving health

Physicians and other medical professionals who care delivery innovations, and episodic telemedicine is

practice telemedicine also run into a patchwork of state one such innovation. As employers and insurance com-

laws. No 2 states are the same: A state-by-state evalua- panies see cost savings associated with these sites, they

tion of telemedicine policies found nearly 50 combina- are more likely to partner with them or reimburse for

tions of requirements, standards, and licensure policies their use. An e-visit typically costs approximately $40

(patientphysician encounter requirement, telepre- (vs. $73 for an in-person visit), and other analyses show

senter requirement, informed consent, and licensure a greater difference in the cost of an e-visit versus in-

and out-of-state practice) (33). For example, the Geor- person visit (37). Although episodic telemedicine pro-

gia Composite Medical Board requires that a face-to- vides on-demand, convenient care, this does not nec-

face encounter with a patient occur before a telehealth essarily equate to long-term, high-value care. This type

service is delivered, with some exceptions (34); in Ohio, of telemedicine may be suitable for part of overall care,

a face-to-face examination is not needed to provide a not independent care or as a long-term replacement

telemedicine service if the physician can gather the for a primary care physician. When these types of spo-

same information through the telemedicine encounter radic telemedicine visits occur, the continuity of a pa-

as they would through a face-to-face visit encounter tient's care may be disrupted and result in larger issues

(35). State medical boards may serve as a resource later on if the information from the visit is not appropri-

for physicians or patients who are unaware of their ately communicated to the patient's physician or med-

state's statutes about telemedicine or Internet ical home and may undermine the establishment or

prescribing. maintenance of a patientphysician relationship.

Reimbursement for telemedicine also varies by Little research has been done on how remote-

state. Forty-six states and the District of Columbia have consultation Web sites or applications may affect the

some type of Medicaid reimbursement for telehealth, continuity of a patient's care, and anecdotal evidence

suggests that antibiotics may be overprescribed in this

and 21 states and the District of Columbia require pri-

setting (38). Maintaining continuity of care has been

vate insurers to cover telemedicine services as dened

shown to be effective in improving health outcomes

by those states (36). Medicare coverage for telemedi-

and is essential in patient-centered care. As remote

cine is narrow and limited to certain beneciaries, tech-

consultation servicesand more broadly, telemedicine

nologies, and areas. State legislatures have been active

as a wholeare integrated into the existing system of

in working to advance telehealth reimbursement poli-

health care delivery, it will be important to continue to

cies. The American Telemedicine Association reports

encourage patients to establish and maintain relation-

that, as of September 2014, a total of 15 states had ships with physicians in their local communities who

introduced legislation mandating private coverage of can coordinate care and handle complex medical is-

telemedicine services and 11 states had introduced sues that cannot be addressed over the remote consul-

legislation mandating Medicaid coverage for tele- tation medium.

health. Several state telemedicine boards have ex-

pressed interest in reviewing existing policies and Positions

potentially updating them to address the growing de- 1. ACP supports the expanded role of telemedicine

mand for telemedicine. as a method of health care delivery that may enhance

Annals of Internal Medicine www.annals.org

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ on 09/15/2015

This online-rst version will be replaced with a nal version when it is included in the issue. The nal version may differ in small ways.

patientphysician collaborations, improve health out- Telemedicine has been shown in some cases to aid

comes, increase access to care and members of a pa- in extending the range of primary care physicians and

tient's health care team, and reduce medical costs subspecialists to patients they could not reach other-

when used as a component of a patient's longitudinal wise, provide care equitable to that of in-person visits,

care. and reduce costs through heightened efciency. Large-

a. ACP believes that telemedicine can be most ef- scale demonstration projects have yielded successful

cient and benecial between a patient and physician results and educational tools and guidance that can be

with an established, ongoing relationship. applied to various care settings. The potential benets

b. ACP believes that telemedicine is a reasonable of telemedicine have been recognized not only by the

alternative for patients who lack regular access to rele- public and many members of the medical community

vant medical expertise in their geographic area. but also federal and state legislators. The Patient Pro-

c. ACP believes that episodic, direct-to-patient tele- tection and Affordable Care Act supports expanded

medicine services should be used only as an intermit- use of telemedicine, especially in new Medicare care

tent alternative to a patient's primary care physician models (such as accountable care organizations) ex-

when necessary to meet the patient's immediate acute plored under the Center for Medicare & Medicaid In-

care needs. novation and Medicaid health home initiatives (42).

Increased demands on the health care system by Although little empirical evidence exists about the

patients, insurers, and employers to provide high qual- inuence of independent remote-consultation Web

ity at a low cost in a convenient setting require innova- sites to support or fracture the continuity of care be-

tive thinking and new approaches to delivery. As tween a physician and patient, their popularity among

technology has become a mainstay in most persons' patients seeking quick, convenient care independent of

day-to-day lives, the public has become more accept- their usual primary care physician merits a deeper dis-

ing and open to telemedicine as a form of health care cussion about the role of these services in the health

delivery for preventive care, acute care, and chronic care delivery system. Physicians who incorporate tele-

disease management. A 2008 study on the attitudes of medicine as a component of care through direct con-

urban and rural populations found that both were re- tact with the patient, as a way to consult with subspe-

ceptive to using telemedicine for primary care services cialists, or as a method of referring patients to

(39). Although initially slow to adopt telemedicine tech- subspecialists offer the most complete and benecial

nologies into the health care delivery system, many telemedicine care. This type of telemedicine keeps the

physicians, patients, and health care settings now use care for the patient centralized and a full medical his-

telemedicine to provide consultations, diagnoses, and tory available to the patient's physician or care team.

treatment of medical conditions ranging from acute to Patient-initiated telemedicine care through on-demand

severe. Forty-two percent of hospitals use some form of Web site or health applications challenges the concept

telemedicine (40), and a survey of physicians found that of whole-person care by creating individual silos with

approximately 40% believed that using technology to each visit that may or may not be integrated into the

communicate with patients would improve outcomes patient's medical history. Although it is possible to es-

(41). tablish a patientphysician relationship via telemedi-

In 2008, ACP published the position paper, E- cine, as noted later in this paper, translating those as-

Health and Its Impact on Medical Practice (2), which sociations into meaningful relationships may prove

highlighted the potential benets of telemedicine on difcult.

patientphysician collaborations, such as increasing pa- Although patient-initiated telemedicine may be

tient access, improving communication by broadening convenient for the patient, it presents several chal-

communication beyond ofce visits and telephone care lenges to maintaining continuity of care and a strong

to include other effective and convenient strategies us- patientphysician relationship. It also may not deliver

ing technology; improving patient satisfaction by en- the same benets as telemedicine used as a compo-

hancing access to high-quality health care from his or nent of a patient's care recommended by the patient's

her physicians and health team, improving the ef- physician. Several variable factors (such as the medical

ciency of health care for patients, physicians, and em- history provided to the consulting physician by the pa-

ployers through more appropriate use of resources tient, ability of the consulting physician to access the

and lowering the cost for payers; facilitating patient patient's electronic health record, or even technology

participation in health care decision making and self- failure) may increase the likelihood that the visit may

management; and enabling virtual teams to contribute become an orphan event in the medical history, leaving

to enhanced patient-care processes. ACP believes that the patient's physician or health care team without

these collaborations are most benecial in longitudinal knowledge of the visit, prescriptions that may have

patientphysician relationships and can drive high- been written, or recommendations. In addition, not be-

value care. ing able to do a physical examination hinders certain

www.annals.org Annals of Internal Medicine

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ on 09/15/2015

This online-rst version will be replaced with a nal version when it is included in the issue. The nal version may differ in small ways.

therapeutic elements associated with touch or interper- direct previous contact or existing relationship with a

sonal communication (43) and raises concerns about patient must do the following:

the accuracy of diagnoses when the physician cannot a. Take appropriate steps to establish a relation-

touch the patient to, for example, detect tenderness or ship based on the standard of care required for an in-

swollen glands. person visit, or

Much like retail health clinics that treat same-day, b. Consult with another physician who does have a

walk-in patients for low-acuity medical conditions, the relationship with the patient and oversees his or her

telemedicine care setting creates limitations to care de- care.

livery and may not be appropriate for all patients or Ethical considerations of telemedicine often center

conditions. The lack of physical interaction can affect on the establishment of a patientphysician relationship

the type of care a patient may receive and the degree and if, when, and how a relationship may be estab-

to which a physician can examine the patient. For ex- lished through telemedicine. The ACP Ethics Manual

ample, it may not be appropriate for a man aged 57 Sixth Edition (44) states that an individual patient

years with a history of cardiovascular disease reporting physician relationship is formed on the basis of mutual

upper respiratory distress to seek care through an on- agreement. The FSMB states that a patientphysician

demand telemedicine service. Conversely, a relatively relationship generally starts when a patient seeks assis-

healthy man aged 35 years with symptoms of sinusitis tance for a health-related matter and is denitively es-

would probably be able to have his problem resolved tablished when the physician agrees to undertake di-

through an on-demand site with few serious concerns agnosis and treatment of the patient and the patient

to his health, although the physician providing the tele- agrees to be treated, regardless of whether there has

medicine service should encourage the man to seek been an encounter in person between the physi-

in-person physician care if the physician believes that cian . . . and patient (45).

the patient needs a physical examination to conrm di-

The FSMB and American Medical Association ac-

agnosis. The circumstances under which a patient may

knowledge that a patientphysician relationship may be

seek on-demand telemedicine should be made on a

established through certain telemedicine technologies

case-by-case basis according to the patient's medical

if conditions similar to an in-person visit are met. How-

needs.

ever, standards of care for in-person visits also apply to

Because convenience is consistently cited as the

encounters that do not take place in person, including

driving factor for seeking care through on-demand

those regarding privacy, informed consent, documen-

telemedicine sites, physicians in all types of practices

tation, continuity of care, and prescribing. For example,

should consider ways to integrate convenient care op-

writing prescriptions based only on an online ques-

tions into their practice, such as the patient-centered

tionnaire or phone-based consultation does not consti-

medical home model, same-day scheduling, or e-visits

tute an acceptable standard of care (44). Care deliv-

and e-consultations. The patient-centered medical

ered via telemedicine should provide information

home model strives to coordinate care across the

health system and provide patients with access to care equal to an in-person examination, conform to the stan-

that matches their needs, including increased access to dard of care expected of in-person care, and incorpo-

after-hours care and convenient care options (such as rate diagnostic tests sufcient to provide an accurate

telephone consultations with a health professional with diagnosis. Some courts have deemed remote technol-

knowledge of the patient's medical record). Physicians ogies as adequate for establishing a patientphysician

are also encouraged to engage patients on the impor- relationship even if the 2 persons never meet. A case

tance of having longitudinal relationships with physi- tried in Texas found that a pathologist contracted with a

cians they trust, who have overall responsibility for their patient's physician who did not have any physical inter-

care, and work in partnership with patients and collab- action with the patient did have a patientphysician re-

oratively with other health care professionals. The lationship because the pathologist's work beneted the

patient-centered medical home model is ideally suited patient (46).

to providing such a relationship, providing the conve- Telemedicine brings the opportunity for increased

nience and tools patients want while reducing the po- access to care, but these benets must be balanced

tential for fracturing their continuity of care by seeking according to the nature of the particular encounter and

episodic care through direct-to-patient sites. the risks from the loss of the in-person encounter (such

2. ACP believes that a valid patientphysician rela- as the potential for misdiagnosis; inappropriate testing

tionship must be established for a professionally re- or prescribing; and the loss of personal interactions

sponsible telemedicine service to take place. A that include the therapeutic value of touch, communi-

telemedicine encounter itself can establish a patient cations with body language, and continuity of care). To

physician relationship through real-time audiovisual date, little evidence exists about the effects of tele-

technology. A physician using telemedicine who has no medicine on patientphysician relationships (47).

Annals of Internal Medicine www.annals.org

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ on 09/15/2015

This online-rst version will be replaced with a nal version when it is included in the issue. The nal version may differ in small ways.

3. ACP recommends that telehealth activities ad- maintaining the continuity of care between the patient's

dress the needs of all patients without disenfranchising physician or medical home, telemedicine may not be

nancially disadvantaged populations or those with low appropriate.

literacy or low technologic literacy. In particular, tele- Telemedicine is mainly recognized as a delivery

health activities need to consider the following: method used to augment traditional carenot a medi-

a. The literacy level of all materials (including writ- cal specialty that would or should replace existing med-

ten, printed, and spoken words) provided to patients or ical practice. As is the case with in-person care, physi-

families. cians and patients are in the most appropriate position

b. Affordability and availability of hardware and In- to determine whether the patient would benet from

ternet access. telemedicine as part of their care. Physicians should

c. Ease of use, which includes accessible interface take into account evidence-based practices and the

design and language. best interest of an individual patient and his or her cir-

ACP reafrms its position from the 2008 e-health cumstances when considering whether to incorporate

paper advocating for protocols and materials that make telemedicine.

telemedicine accessible and affordable to all popula- Many new and inventive telemedicine technologies

tions, including those who may be disenfranchised. An and applications are developed every day; however,

examination of 62 telehealth Web sites assessed vari- until they are tested and shown to be effective in their

ous components of these sites and identied issues to intended uses, it should not be assumed that they are

consider for future designs (48). With research showing better simply because of their novelty. Although tech-

that expansion of telemedicine can benet many pa- nology has advanced considerably, certain aspects of

tient groups, including underserved populations, those the medical encounter, such as the physical examina-

who use telemedicine or create and distribute informa- tion, cannot be entirely replicated through telemedi-

tion on telehealth services should be cognizant of the cine. However, if a physician believes that physical ex-

factors that may hamper patients' understanding or use amination is essential for clinically appropriate care,

of telemedicine and how it applies to their individual telemedicine should not be used exclusively to diag-

needs (49). nose the patient.

4. ACP supports the ongoing commitment of fed- The ACP ethics manual (44) regarding the physi-

eral funds to support the broadband infrastructure cian and the patient states the following:

needed to support telehealth activities. The physician's primary commitment must always

To provide high-speed, reliable connections for be to the patient's welfare and best interest, whether in

telehealth and mHealth, a strong broadband infrastruc- preventing or treating illness or helping patients to

ture must be in place. This is particularly important in cope with illness, disability, and death. . . . The interest

rural communities, where a lack of physicians may re- of the patient should always be promoted regardless of

quire patients to use telemedicine as their main source nancial arrangements; the health care setting; or pa-

of primary care or access to subspecialists. In March tient characteristics, such as decision-making capacity,

2010, the Federal Communications Commission re- behavior, or social status.

leased the National Broadband Plan with the goals of 6. ACP recommends that physicians ensure that

designing policies to spur innovation of, investment in, their use of telemedicine is secure and compliant with

and access to broadband capabilities (50). In 2014, the federal and state security and privacy regulations.

Federal Communications Commission announced As the use of telemedicine, and particularly the use

$400 million in annual funding for the Healthcare Con- of 2-way interactive video, by patients and physicians

nect Fund with the aim of increasing broadband Inter- increases, it is important that patients' protected health

net services to rural clinicians, among others (51). This information is kept secure and condential. Recent

type of continued investment is needed to support a large-scale technologic security breaches have raised

strong network for U.S. clinicians offering telehealth public concern about the safety of consumers' personal

services and to keep up with the demand of existing information when collected and stored as a part of a

telehealth services and the rapidly expanding mHealth telemedicine encounter. An analysis of research found

market. a lack of standardization in telemedicine security (52).

5. ACP believes that physicians should use their Many questions arise when the security of a telemedi-

professional judgment about whether the use of tele- cine encounter is considered, such as the following:

medicine is appropriate for a patient. Physicians should Are the patient and physician using secure devices? Is

not compromise their ethical obligation to deliver clin- information stored in a secure manner? Are the services

ically appropriate care for the sake of new technology compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Ac-

adoption. countability Act (HIPAA) or the Health Information

a. If an in-person physical examination or other di- Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act? Is

rect face-to-face encounter is essential to privacy or information properly encrypted? What is the security of

www.annals.org Annals of Internal Medicine

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ on 09/15/2015

This online-rst version will be replaced with a nal version when it is included in the issue. The nal version may differ in small ways.

network connections between sites? In addition, physi- tions and medical specialty organizations have devel-

cians should be aware of state laws or regulations oped guidance for use of telemedicine in certain areas,

around the recording of telemedicine sessions, images, such as telemental health, teledermatology, and home

or audio or visual information gathered and the inclu- telehealth. The American Telemedicine Association has

sion of such recordings into a patient's health record. worked with groups to develop standards and clinical

Physicians must be conscientious of the type of guidelines for medical specialties, including primary

technologies they use to facilitate telemedicine and and urgent care. As telemedicine continues to develop,

whether they meet the terms of state and federal laws. ACP believes that medical specialty societies and state

For example, Skype (Microsoft) is a widely used Internet medical boards should collaborate to establish guid-

service that connects users through audio, video, and ance for best practices in the use of telemedicine.

instant messaging. However, Skype is not considered 8. ACP recommends that physicians who use tele-

HIPAA-compliant because Microsoft has not entered medicine should be proactive in protecting themselves

into a business associates agreement as required by against liabilities and ensure that their medical liability

the HIPAA Omnibus Rule. In 2014, a physician in Okla- coverage includes provision of telemedicine services.

homa who was providing telepsychiatry services and Physicians who provide care through telemedicine

prescriptions over Skype was sanctioned by the state have the same duty of care to their patients as if they

medical board. He was placed on 2 years of probation were seeing them face to face but may encounter more

and required to complete a prescribing practices questions on their liability when providing remote care.

course after it was determined that Skype was noncom- There is a dearth of information on medical liability in

pliant with Oklahoma's telemedicine policy (53). the arena of telehealth. The examples of legal chal-

7. ACP recommends that telemedicine be held to lenges are primarily alleged illegalities in prescribing

the same standards of practice as if the physician were drugs over the Internet and not a result of physicians

seeing the patient in person. providing negligent care through telemedicine (54). In

a. ACP believes that there is a need to develop addition, individual medical malpractice carriers may

evidence-based guidelines and clinical guidance for have policies in place that provide differing coverage

physicians and other clinicians on appropriate use of depending on the state in which the physician is prac-

telemedicine to improve patient outcomes. ticing, the state in which he or she is providing a tele-

ACP supports similar standards for telemedicine as health service, or provisions of the carrier's service.

in-person encounters, such as maintaining the privacy In 2010, the University of Maryland School of Law's

and security of the patient's health information and the Law & Health Care program convened a roundtable

medical record, adhering to evidence-based clinical discussion on the legal impediments to telemedicine,

practice guidelines, and prescribing practices. State which included medical malpractice and liability. Partic-

medical boards or legislatures may pass policies and ipants identied areas that may present challenges to

mandate certain requirements that are unique to medical liability providers specic to telemedicine, in-

telemedicinefor example, that a face-to-face encoun- cluding litigation issues, quality of medicine, quality of

ter must take place before using telemedicine, even if technology, and training (55). Other legal consider-

the telemedicine encounter would be a clinically ap- ations include how to determine which state's laws will

propriate alternative. An analysis of state practice stan- be used when the physician and patient are in different

dards and licensure found a wide-ranging variation in locations. Although these challenges are unique to

these policies (33). telehealth, most liability does not considerably differ

Telemedicine policymakers should be cautious not from that of in-person care. Physicians using telemedi-

to set higher standards for telemedicine than for in- cine should ensure that they are adhering to all privacy

person encounters if there is no medical purpose. For laws as they would if they were seeing patients in per-

example, some states require the presence of a tele- son and adhere to the same level of professionalism.

presenter (an individual present with a patient or on the For example, a physician would not examine a patient

premises trained to assist a physician during a tele- in a public place without the patient's express consent;

medicine encounter) with the patient at each telemedi- therefore, physicians would not see patients over tele-

cine visit (33). Although the presence of a telepresenter medicine media in public places or potentially expose

may be appropriate in some cases to ensure proper patients and their health information without the pa-

functioning of equipment, aid the patient throughout tients' consent.

the visit, or present the patient's case to the distant site With little precedent providing guidance for how to

physician, mandating the presence of telepresenter at protect physicians against liabilities that may arise

every telemedicine encounter creates an unnecessary when using telemedicine, physicians should be cau-

barrier to use. tious and proactive by evaluating their existing medical

Longstanding ACP policy supports evidence-based liability coverage; obtaining documentation ensuring

practices in health care. Some state medical associa- that their coverage pertaining to telemedicine in each

Annals of Internal Medicine www.annals.org

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ on 09/15/2015

This online-rst version will be replaced with a nal version when it is included in the issue. The nal version may differ in small ways.

state in which physicians practice, if applicable; and en- In 2014, the FSMB nalized an interstate licensure

suring that they are following all state regulations about compact that expedites the process of obtaining sev-

the recording and storing of information gathered eral medical licenses by streamlining the system (58).

through telemedicine. The compact received bipartisan support during the re-

9. ACP supports the ongoing commitment of fed- view process, and many applaud the effort to simplify

eral funds to establish an evidence base on the safety, the process for physicians seeking several licenses, im-

efcacy, and cost of telemedicine technologies. prove access to telemedicine services, and uphold pa-

Although telemedicine has been studied exten- tient protection. The compact is supported by more

sively, additional research is necessary to establish an than 25 medical and osteopathic boards and is being

evidence base on best practices to inuence stakehold- considered by several state legislatures (59). ACP sup-

ers and policymakers on how best to implement and ports the FSMB interstate compact and its efforts to

reimburse for telehealth services. There are many ex- ease administrative burdens that may hinder physicians

amples of the usefulness of telemedicine and tele- from obtaining multiple medical licenses.

health in individual specialties, such as dermatology, Although holding multiple medical licenses may fa-

radiology, stroke, mental health, and cardiology; how- cilitate increased adoption of telemedicine by expand-

ever, some believe that evidence gaps in the overall ing the scope of where a physician can practice, there

benet of telemedicine are large enough to prevent are other ways for physicians to practice telemedicine

adoption of legislation or policies that would support across state lines without requiring changes to the ex-

wider adoption. A systematic review of reviews on tele- isting medical licensure system or obtaining an unre-

medicine including all e-health interventions found 21 stricted medical license. The number of physicians who

reviews reporting that telemedicine is effective and an hold 3 or more active medical licenses is relatively small

additional 18 stating that evidence is promising but (6%), and it has been suggested that those with 5 or

more active licenses are probably radiologists or pa-

incomplete (56). The review called for additional large-

thologists who practice telemedicine (58). Physicians

scale research into telemedicine. The Health Resources

who want to practice telemedicine but do not want to

and Services Administration, National Institutes of

obtain a full, unrestricted medical license to do so

Health, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Patient-

should determine whether the state in which they wish

Centered Outcomes Research Institute, and Center for

to practice telemedicine use 1 or more of the following

Medicare & Medicaid Innovation support projects and

arrangements:

research in innovative uses of technology and tele-

Special purposes license: Some states allow health

medicine. The potential cost savings to the U.S. health

professionals to obtain a limited license in the state for

care system warrant continued investment into and ex-

the delivery of specic health services.

ploration of telemedicine.

Reciprocity: Two or more states may enter into rec-

10. ACP supports a streamlined process to obtain-

iprocity, an agreement that gives physicians certain

ing several medical licenses that would facilitate the

privileges in 1 state given that physicians from the other

ability of physicians and other clinicians to provide tele- state are given the same privileges in their state.

medicine services across state lines while allowing Mutual recognition: Licensing authorities volun-

states to retain individual licensing and regulatory tarily agree to accept the policies and processes of the

authority. state in which the physician is licensed.

Telemedicine and state medical licensure propos- Licensure by endorsement: States grant licenses to

als are often intertwined, and modications to licensure health professionals licensed in other states with equal

portability are widely considered a way to remove bar- licensing standards (60).

riers that may hinder the adoption of telemedicine. 11. ACP supports the ability of hospitals and critical

Medical licensing has traditionally been considered a access hospitals to privilege by proxy in accordance

state authority under the Tenth Amendment, which with the 2011 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Ser-

gives states powers that are not granted to the federal vices nal rule allowing a hospital receiving telemedi-

government by the Constitution. The existing system of cine services (distant site) to rely on information from

state medical licensure requires a physician to apply hospitals facilitating telemedicine services (originating

directly to a medical or osteopathic board to obtain a site) in providing medical credentialing and privileging

license in an individual state or territory. In the past 20 to medical professionals providing those services.

years, there has been a movement to simplify the pro- The Joint Commission (TJC), a hospital-accrediting

cess of obtaining a medical license. All states now use organization, previously allowed hospitals providing

the United States Medical Licensing Examination, 25 telehealth services to privilege by proxy, which al-

state boards use a uniform application, and more than lowed for originating sites to accept the distant site's

one half of new-license applications use the FSMB privileging and credentialing decisions for physicians

credential-verication service (57). and health professionals who provide telemedicine ser-

www.annals.org Annals of Internal Medicine

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ on 09/15/2015

This online-rst version will be replaced with a nal version when it is included in the issue. The nal version may differ in small ways.

vices. However, revisions to the Conditions of Participa- geographic restrictions by allowing physicians and

tion from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services other health professionals to be reimbursed for tele-

(CMS) rendered the TJC's process invalid. Through the medicine services provided at 1 of 8 originating sites,

rulemaking process, the CMS approved regulations including the patient's home, if the physician or health

similar to those that the TJC previously used in 2011. professional is signed up for a next-generation ac-

The TJC also approved the same regulations in 2011 countable care organization. This preliminary expan-

(61). sion of telemedicine services to Medicare patients is a

Privileging by proxy is an optional process that rst step in providing care to thousands of beneciaries

does not prevent hospitals or facilities from using their and realizing the potential benets of telemedicine for

own credentialing and privileging processes. Some the Medicare system. It is important that patients are

hospitals may believe that the requirements to partici- not denied access to telemedicine and its potential

pate in the privileging-by-proxy process are more bur- benets simply because of where they are located

densome than their existing process and choose not to when they receive care.

take part. However, hospitals and critical access hospi- 13. ACP supports reimbursement for appropriately

tals should consider whether privileging by proxy could structured telemedicine communications, whether syn-

reduce the administrative cost or burden of credential- chronous or asynchronous and whether solely text-

ing health professionals. Privileging by proxy can save based or supplemented with voice, video, or device

signicant time and resources for both the originating feeds in public and private health plans, because this

and distant-site hospitals. Small hospitals and critical form of communication may be a clinically appropriate

access hospitals can benet substantially from the rule service similar to a face-to-face encounter.

by reducing the administrative burden of duplicative One of the most signicant challenges to wide-

activities for the originating site. The process can also spread telemedicine adoption is reimbursement. Re-

reduce the burden for telemedicine practitioners, who

search shows that telemedicine is most cost-effective

are not required to repeatedly go through the privileg-

when payers reimburse for those services. Telemedi-

ing and credentialing process.

cine has been reimbursed in various ways since 1999,

12. ACP supports lifting geographic site restrictions

but recent efforts by telemedicine proponents have re-

that limit reimbursement of telemedicine and tele-

sulted in expanded public and private payment for

health services by Medicare to those that originate out-

telehealth services. However, a patchwork of laws gives

side of metropolitan statistical areas or for patients who

physicians in some areas high incentives to adopt tele-

live in or receive service in health professional shortage

medicine, whereas incentives are lower or nonexistent

areas.

in other areas.

Limited access to care is not an issue specic to

Medicare: Medicare reimbursement for telehealth

rural communities; underserved patients in urban areas

is narrowly conned to certain Part B services, technol-

have the same risks as rural patients if they lack primary

ogies, and areas. A telemedicine service must originate

or specialty care regardless of where they live. The

geographic site restrictions limiting reimbursement of at a site outside metropolitan statistical areas or in a

telehealth services in Medicare were adopted in 2000 rural census tract that is also dened as a rural health

and sought to keep costs of telehealth in Medicare professional shortage area. The telehealth service must

down, which at the time were estimated to be $150 be a type of video-conferencing or 2-way communica-

million over 5 years. However, actual expenditures tion system; reimbursement for store-and-forward tech-

ended up being a small fraction of the estimated costs, nology is allowed only in Alaska, Hawaii, and federal

at approximately $2 million per year over the rst 6 demonstration programs.

years (62). The restrictions to Medicare payment for Medicaid: Medicaid reimbursement policies vary

telehealth services have been largely unchanged, re- widely, but 46 states and the District of Columbia reim-

sulting in ongoing low reimbursement, with approxi- burse for interactive or live video, 10 states reimburse

mately $12 million paid in 2013 (63). for store-and-forward technology, 13 states reimburse

Expanded payment for telehealth services in Medi- for remote monitoring, and 3 states reimburse for all 3.

care has been the focus of several legislative and policy State legislatures have been active in proposing legis-

proposals over the past few years and will probably lation to expand the scope of Medicaid reimbursement

remain at the forefront of ongoing telemedicine de- for different forms of telemedicine (64).

bates. The CMS has worked to include more telehealth Private insurance: Twenty-one states and the Dis-

services under Medicare. The scal year 2014 Medicare trict of Columbia require private insurance plans to

Physician Fee Schedule expanded the number of eligi- cover telehealth services. Insurers have also begun

ble geographic locations with telemedicine-originating partnering with telemedicine companies, giving their

sites to rural areas that are located within metropolitan members access to remote consultation services, which

statistical areas. The CMS has moved to lift some of the may decrease costs for the insurer and increase satis-

Annals of Internal Medicine www.annals.org

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ on 09/15/2015

This online-rst version will be replaced with a nal version when it is included in the issue. The nal version may differ in small ways.

faction for patients who nd the technology convenient important that steps are taken to safeguard against

and effective for the type of treatment they are seeking. abuse. Early concerns about potential abuse or overuse

The early adoption of telemedicine technologies of telehealth services resulted in unwarranted limita-

served as a way to increase access to health care for tions on telehealth services in public health care sys-

rural communities. Although the use of telemedicine tems. The successful integration of telemedicine into

has increased signicantly since the introduction of the health care system will require consistency among

telecommunications technologies to rural areas, public public and private payers for physicians and health care

payment policy has not kept pace with expanded use. professionals and a mindful approach to reimburse-

A growing amount of evidence suggesting the effec- ment for services rendered either through traditional or