Professional Documents

Culture Documents

God As An Attachment Figure

Uploaded by

Em ManuelOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

God As An Attachment Figure

Uploaded by

Em ManuelCopyright:

Available Formats

God as an attachment figure

Ainsworth (1985) summarized five defining characteristics that are

widely acknowledged to distinguish attachment relationships from other

types of close relationships: (1) the attached person seeks proximity to

the caregiver, particularly when frightened or alarmed; (2) the caregiver

provides care and protection (the haven of safety function) as well as (3)

a sense of security (the secure base function); (4) the threat of separation

causes anxiety in the attached person; and (5) loss of the attachment figure

would cause grief in the attached person. In the remainder of this

chapter I test the idea that God (or other religious figures) really does

function as an attachment figure to many worshipers.pp.56

May mga ginawang batayan si Ainsworth (1985) sa paglilinaw ng pagkakaiba ng attachment

relationships sa other types of close relationship.

(1) ang Attached person ay naghahanap ng proximity sa kaniyang care giver

Thus, the question remains as to why the Christian God (and gods

of many other religions) is often attributed with omnipresence. I suggest

that it makes it possible for all believers to feel that they are in close

proximity to God simultaneously. According to most Christian faiths,

God (or Jesus) is always by your side, holding your hand and watching

over you. Believers are reminded constantly in Scripture, sermons, and

religious literature that God is always nearby and available when needed.

It would be difficult for people to logically maintain that this is true for

all believers simultaneously were God not omnipresent. Note that an alternative

is for each person to have his or her own guardian angel or

similar kind of personal deity, dedicated full-time to one individual

without being distracted by other responsibilities.pp. 58

Yet the role of the church as a place one can go to be close to God should not be underestimated.

People often visit churches spontaneously at times other than

formal services, especially when troubled, to speak with and feel the presence

of the deity. Theoretically one could do this anywhere, so why else

is the church a preferred location for this purpose?

God as a haven of safety

Hood et al. (1996) conclude that people are most

likely to turn to their gods in times of trouble and crisis, and list three

general classes of potential triggers: illness, disability, and other negative

life events that cause both mental and physical distress; the anticipated

or actual death of friends and relatives; and dealing with an adverse life

situation (pp. 386387)

Argyle and BeitHallahmi (1975) emphasized that people specifically

turn to prayer, rather than the church, in stressful circumstances.

This is a crucial insight from an attachment perspective because it suggests

that it is the relationship with God per se, and not some other aspect

of religiousnesssuch as church membership, group processes, or

cognitive meaning structuresto which people are turning under these

circumstances. pp.62

Allport (1950) conducted interviews

with a large number of World War II combat veterans about the role of

their religious beliefs while on the battlefield, and came away with the

conclusion that the individual in distress craves affection and security.

Sometimes a human bond will suffice, more often it will not (p. 57).

The no-atheists-infoxholes

maxim was literally supported by Stouffer et al. (1949), who

showed that soldiers in battle do in fact pray frequently and feel that such

prayer is beneficial. In a study of religious attributions, Pargament and

Hahn (1986) concluded that subjects appeared to turn to God more as a

source of support during stress than as a moral guide or as an antidote to

an unjust world (p. 204).

According

to Bowlby (1973) and others, the availability of a secure base is the

antidote to fear and anxiety: When an individual is confident that an

attachment figure will be available to him whenever he desires it, that person will be much less prone to

either intense or chronic fear than will

an individual who for any reason has no such confidence (p. 202).

Christian

Scripture, particularly in the Psalms (Wenegrat, 1990). Perhaps best

known is the 23rd Psalm: Yea, though I walk through the valley of the

66 ATTACHMENT, EVOLUTION, AND THE PSYCHOLOGY OF RELIGION

shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me; thy rod and thy

staff, they comfort me. Countless other examples from the Psalms could be

cited, in which God is described or addressed as a shield for me (3:3), my

rock, and my fortress, (18:2), and the strength of my life (27:1).

Although I am focusing mainly on Christianity in the present chapter,

it is important to note that the idea of God or gods as providing a secure

base is by no means limited to this religious tradition. In his study of

the Nuer people of the southern Egyptian Sudan, Evans-Pritchard (1956)

offers the following:

The believer, who has communicated with his god, is not merely a man

who sees new truths of which the unbeliever is ignorant; he is a man who

God as an Attachment Figure 67

is stronger. He feels within him more force, either to endure the trials of

existence, or to conquer them. It is as though he were raised above the

miseries of the world, because he is raised above his condition as a mere

man; he believes that he is saved from evil, under whatever form he may

conceive this evil. (p. 61)

Specifically, respondents reporting an avoidant attachment

relationship with God (i.e., God is perceived as impersonal, distant,

and doesnt care about me) scored significantly lower on a variety

of measures of well-beingincluding loneliness, depression, psychosomatic

symptoms, and life satisfactionthan respondents reporting secure

(God is perceived as warm, responsive, caring) or anxious (God is perceived

as sometimes warm and responsive, sometimes not) attachments

to God. These results closely paralleled results for a similar variable

measuring individual differences in security of attachment in human love

relationships.

An attachment figure who is simultaneously

omnipresent, omniscient, and omnipotent would provide the

most secure of secure bases. As the theological Kaufman (1981) noted,

God is an absolutely adequate attachment-figure.

Ainsworth (1985) concern responses to separation

from, or loss of, the attachment figure per se: The threat of separation

causes anxiety in the attached person, and loss of the attachment

figure causes grief. If God functions psychologically as an attachment figure,

then separation from or loss of God should engender these same

kinds of responses.

Determining whether God meets these criteria is a difficult matter,

because one does not become separated from, or lose a relationship with,

God in the same ways that people typically lose human relationship partners.

God does not die, sail off to fight wars, move away, or file for divorce.

Indeed, this is a primary reason why God is an absolutely adequate

attachment-figure in the first place.

God images are perceived as more closely related to maternal

than paternal images (Godin & Hallez, 1965; Nelson, 1971;

Strunk, 1959)

Wenegrat (1990) has observed that the deities of the oldest known

religions were largely maternal figures and that modern Protestantism is

unusual in its lack of significant female deities. Freud himself puzzled

over this fact, confessing that I am at a loss to indicate the place of the

great maternal deities who perhaps everywhere preceded the paternal deities

(quoted in Argyle & Beit-Hallahmi, 1975, p. 187).

Childrens Beliefs about God

Heller (1986) observed a number of personality themes in childrens

images of God that seem to illustrate attachment phenomena (although

he did not interpret them in attachment terms). His God, the Therapist

image refers to an all-nurturant, loving figure which closely resembles asecure attachment figure. Two

alternative God images described by

Heller appear to parallel the two insecure patterns of attachment: The

Inconsistent God seems to correspond to anxious/ambivalent attachment,

and God, the Distant Thing in the Sky parallels avoidant attachment.

Heller also noted several themes that appeared to him to transcend common

familial and cultural influences, including intimacy (feelings of

closeness to God) and omnipresence (God is always there). While Heller

seemed to find some of these themes enigmatic, there is nothing

mysterious about them from an attachment perspective.

inferences

about other deities both within and outside of Christianity.

Wenegrat (1990) suggests that due to its lack of significant female deities,

modern Protestantism provides a particularly poor vehicle for attachment

concerns (p. 143). In contrast, he notes that Catholicism provides

division of psychological labor, in which a desexualizedVirgin Mary adopts

maternal characteristics (and attachment functions) while God assumes

other paternal functions. I thinkWenegrat may have been misled here by

the red herring of the paternalmaternal or masculinefeminine distinction,

and consequently overlooks the degree to which Jesus serves as an attachment

figure in Protestant beliefs. However, his point is well made that

a kind of division of psychological labor is common in polytheistic religions,

with some gods perceived as attachment figures and others in terms

of other psychological functions and dynamics.

in the marvelous possibility that God loves us the way a

mother loves her baby (Greeley, 1990, p. 252). Drawing

Dickie et al. (1997) found in a study of 4- to 11-year-old children that

individual differences in perceptions of parents were related to differences

in images of God. Different patterns were observed with respect to mothers

and fathers and to the dimensions of God images. For example, perceptions

of fathers as nurturant were related to the degree to which God was per-

104 ATTACHMENT, EVOLUTION, AND THE PSYCHOLOGY OF RELIGION

FIGURE 5.2. Continuity of attachment internal working models (IWMs) across time.

ceived as nurturing, whereas perceptions of mothers as powerful were related

to images of God as powerful.

You might also like

- Level of Anxiety and Leadership Style in The PhilippinesDocument4 pagesLevel of Anxiety and Leadership Style in The PhilippinesEm Manuel100% (1)

- Blackawton BeesDocument5 pagesBlackawton BeesEm ManuelNo ratings yet

- A Multitude'' of Solitude A Closer Look at Social Withdrawal and Nonsocial Play in Early ChildhoodDocument7 pagesA Multitude'' of Solitude A Closer Look at Social Withdrawal and Nonsocial Play in Early ChildhoodEm ManuelNo ratings yet

- The ChantDocument7 pagesThe ChantEm Manuel100% (1)

- 100 Defense MechanismDocument15 pages100 Defense MechanismEm Manuel100% (4)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

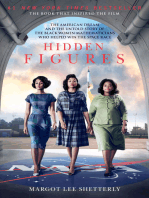

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Testimony of A Former Yogi-03Document1 pageTestimony of A Former Yogi-03Francis LoboNo ratings yet

- Synfocity 704Document4 pagesSynfocity 704Mizoram Presbyterian Church SynodNo ratings yet

- Sri Yantra Pranapratistha and Puja - Simplified ProcedureDocument4 pagesSri Yantra Pranapratistha and Puja - Simplified ProcedurePappu Sinha67% (6)

- Kingdom DeclarationsDocument2 pagesKingdom DeclarationsjoaocarimoNo ratings yet

- A Conversation With General Conference President Jan PaulsenDocument31 pagesA Conversation With General Conference President Jan Paulsenjester hudrNo ratings yet

- Does Jesus Care? What Jesus Does Do To Show He CaresDocument2 pagesDoes Jesus Care? What Jesus Does Do To Show He Caresbright williamsnNo ratings yet

- Anchoring A TraditionDocument5 pagesAnchoring A TraditionRecursos AprendizajeNo ratings yet

- 022008Document52 pages022008Shrinivas YuvanNo ratings yet

- New Testament Study Guide #4Document5 pagesNew Testament Study Guide #4KrisOldroydNo ratings yet

- The Body of JesusDocument12 pagesThe Body of Jesusdemuh19100% (1)

- Nehushtan - The Dark Side of The Pillar 07MAR20Document36 pagesNehushtan - The Dark Side of The Pillar 07MAR20Soni DapajNo ratings yet

- How To Pray The RosaryDocument2 pagesHow To Pray The RosaryFrancis TranNo ratings yet

- Russian Alphabet With Sound and HandwritingDocument4 pagesRussian Alphabet With Sound and HandwritingGDUT ESLNo ratings yet

- The Role of Culture in Gospel CommunicationDocument21 pagesThe Role of Culture in Gospel Communicationspeliopoulos100% (4)

- Origins and MeaningDocument8 pagesOrigins and Meaningzakaraya0No ratings yet

- Maryam Jameelah Why I Embraced IslamDocument13 pagesMaryam Jameelah Why I Embraced IslamIqraAlIslamNo ratings yet

- Wagner's Personality TestDocument67 pagesWagner's Personality Testzed0401uslsNo ratings yet

- Madness and Marginality PrintoutDocument38 pagesMadness and Marginality PrintoutChandreyee NiyogiNo ratings yet

- Yannaras - Relational OntologyDocument17 pagesYannaras - Relational OntologySahaquielNo ratings yet

- The Cambridge Paragraph Bible, AV, Scrivener Ed., 1873Document1,442 pagesThe Cambridge Paragraph Bible, AV, Scrivener Ed., 1873David Bailey100% (2)

- God's Invitation To The SinnerDocument8 pagesGod's Invitation To The SinnerEdson MunyonganiNo ratings yet

- Form CriticismDocument28 pagesForm CriticismFatma Betül Güney AltıntaşNo ratings yet

- 1114 Monica - Res Paper 1Document12 pages1114 Monica - Res Paper 1francis hcaNo ratings yet

- Catching FoxesDocument38 pagesCatching FoxesDennis Leaño PueblasNo ratings yet

- Wicca 101 & 102 - BWTDocument82 pagesWicca 101 & 102 - BWTxxanankexx399097% (36)

- 3 - Liber LXVI - Stellae Rubeae PDFDocument7 pages3 - Liber LXVI - Stellae Rubeae PDFAustin100% (1)

- Art of The Renaissance PeriodDocument25 pagesArt of The Renaissance PeriodMaria BleselaNo ratings yet

- ACTIVIDAD 1 ACT Algebra LinealDocument20 pagesACTIVIDAD 1 ACT Algebra LinealNICOLAS TAPIERONo ratings yet

- Assignment IN Theology: A.F.C. (Ambassadors For Christ)Document12 pagesAssignment IN Theology: A.F.C. (Ambassadors For Christ)Hannah BessatNo ratings yet

- A History of Turkish Bible Translations PDFDocument135 pagesA History of Turkish Bible Translations PDFMarija MarijanovskaNo ratings yet