Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Full Issue

Uploaded by

RioHasibuanCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Full Issue

Uploaded by

RioHasibuanCopyright:

Available Formats

Unless otherwise noted, the publisher, which is the American Speech-Language-

Hearing Association (ASHA), holds the copyright on all materials published in

Perspectives on Neurophysiology and Neurogenic Speech and Language

Disorders, both as a compilation and as individual articles. Please see Rights

and Permissions for terms and conditions of use of Perspectives content:

http://journals.asha.org/perspectives/terms.dtl

Vol. 24, No. 3, pp. 74117

June 2014

In This Issue

Guest Editors Column by Candace Vickers..........................................................................7677

Tutorial for Verb Network Strengthening Treatment (VNeST): Detailed Description of the

Treatment Protocol with Corresponding Theoretical Rationale by Lisa A. Edmonds...............7888

Facilitating Life Participation in Severe Aphasia With Limited Treatment Time

by Jacqueline Hinckley.........................................................................................................8999

Maximizing Outcomes in Group Treatment of Aphasia: Lessons Learned From a

Community-Based Center by Darlene Williamson.............................................................100105

Communication Recovery Groups for Persons with Aphasia: A Replicable Program

for Medical and University Settings by Candace Vickers and Darla Hagge.........................106113

Alternative Service Delivery Model: A Group Communication Training Series for

Partners of Persons with Aphasia by Darla Hagge.............................................................114117

74

Downloaded From: http://sig2perspectives.pubs.asha.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ashannsld/930947/ on 09/19/2017

Terms of Use: http://pubs.asha.org/ss/rights_and_permissions.aspx

Perspectives on Neurophysiology and Neurogenic Speech and Language Disorders is a member publication

for affiliates of American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Special Interest Group 2, Neurophysiology

and Neurogenic Speech and Language Disorders. Planned publication months are January, April, June, and

October. Affiliates of any of ASHAs 18 SIGs have access to read all SIG Perspectives. To learn more about

joining a SIG, visit http://www.asha.org/SIG/join/. Contact Perspectives at sigs@asha.org.

Disclaimer of warranty: The views expressed and products mentioned in this publication may not reflect

the position or views of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association or its staff. As publisher, the

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association does not warrant or guarantee the accuracy, completeness,

availability, merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, or noninfringement of the content and

disclaims responsibility for any damages arising out of its use. Advertising: Acceptance of advertising does

not imply ASHAs endorsement of any product, nor does ASHA accept responsibility for the accuracy of

statements by advertisers. ASHA reserves the right to reject any advertisement and will not publish

advertisements that are inconsistent with its professional standards.

Vol. 24, No. 3, June 2014

SIG 2 Editor: Michael de Riesthal

SIG 2 2014 Editorial Review Board Members:

Angela Ciccia Tepanta Fossett Gina Griffiths Amy Krantz Shannon Mauszycki Peter Meulenbroek

Katie Ross Julie Wambaugh

SIG 2 CE Content Manager: Amanda Hereford

SIG 2 2014 Coordinating Committee: Carole Roth, SIG Coordinator Mary H. Purdy, Associate Coordinator

Michael de Riesthal, Perspectives Editor Gloriajean Wallace Sarah Wallace Monica Sampson, ASHA SIG 2

Ex Officio

ASHA Board of Directors Board Liaisons: Donna Fisher Smiley, Vice President for Audiology Practice

Gail J. Richard, Vice President for Speech-Language Pathology Practice

ASHA Production Editor: Victoria Davis

ASHA Advertising Sales: Pamela J. Leppin

ASHA Board of Directors: Elizabeth S. McCrea, President Judith L. Page, President-Elect Patricia A.

Prelock, Immediate Past President Donna Fisher Smiley, Vice President for Audiology Practice Perry F.

Flynn, Speech-Language Pathology Advisory Council Chair Wayne A. Foster, Audiology Advisory Council

Chair Howard Goldstein, Vice President for Science and Research Carlin F. Hageman, National Student

Speech Language Hearing Association (NSSLHA) National Advisor Carolyn W. Higdon, Vice President for

Finance Barbara J. Moore, Vice President for Planning Robert E. Novak, Vice President for Standards

and Ethics in Audiology Gail J. Richard, Vice President for Speech-Language Pathology Practice Shari B.

Robertson, Vice President for Academic Affairs in Speech-Language Pathology Theresa H. Rodgers, Vice

President for Government Relations and Public Policy Barbara K. Cone, Vice President for Academic Affairs

in Audiology Lissa A. Power-deFur, Vice President for Standards and Ethics in Speech-Language Pathology

Arlene A. Pietranton, Chief Executive Officer (ex officio to the Board of Directors)

75

Downloaded From: http://sig2perspectives.pubs.asha.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ashannsld/930947/ on 09/19/2017

Terms of Use: http://pubs.asha.org/ss/rights_and_permissions.aspx

We conclude with Darla Hagges description of an alternative service delivery model for a

six week communication training series. Partners of persons with aphasia attended the series

learning communication strategies for PWA and experiencing peer support while their family

members with aphasia attended conversation groups which were facilitated by trained volunteers

and graduate students.

All articles in this edition were written with the awareness that SLPs across the United

States are under more constraints than ever while they try to bring about tangible results and

improvement for persons with aphasia across the spectrum of care. We hope clinicians will find

useful ideas that help to expand service to PWA which can be applied in their own settings.

References

Edmonds, L. A., & Babb, M. (2011). Effect of verb network strengthening treatment in moderate-to-severe

aphasia. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 131145.

Leach, E., Cornwell, P., Fleming, J., & Haines, T. (2010). Patient-centered goal setting in a subacute

rehabilitation setting. Disability and Rehabilitation, 32, 159172.

Kagan, A., Black, S., Duchan, J., Simmons-Mackie, N., & Square, P. (2001) Training volunteers as

conversation partners using Supported conversation for adults with aphasia (SCA): A controlled trial.

Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 44, 624638.

Rowden-Racette, K. (2013, September 01). In the limelight: Guides for the long journey back. The ASHA Leader.

77

Downloaded From: http://sig2perspectives.pubs.asha.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ashannsld/930947/ on 09/19/2017

Terms of Use: http://pubs.asha.org/ss/rights_and_permissions.aspx

The VNeST protocol applies this theory by requiring participants to produce diverse scenarios

related to trained verbs (e.g., a nurse weighs a patient, a cashier weighs produce, a jeweler weighs

gold, a veterinarian weighs a puppy), which potentially promotes spreading activation to untrained

neurological networks, thereby facilitating generalized word retrieval in sentences and discourse.

With increased availability of words, persons with aphasia can potentially communicate their ideas

with more ease and/or specificity. Additionally, a verbs syntactic frame (composed of the verbs

and its arguments) is also activated and potentially strengthened during VNeST, which could aid

in sentence construction. Further, the repeated selection of subject/agents and object/patients

in relation to trained verbs involves mapping thematic role information onto syntactic argument

structure, which can be impaired in persons with aphasia (e.g., Webster, Franklin, & Howard,

2004).

Participants

It is beyond the scope of this article to provide a comprehensive review of VNeST studies.

However, a few pertinent details regarding participant outcomes are provided (see original articles

for more information). Three studies investigated VNeST in 17 people with aphasia (10 male)

(Edmonds & Babb, 2011; Edmonds et al., 2014; Edmonds et al., 2009), and one study provided

a computerized version of VNeST (VNeST-C) via teletherapy to two males (Furnas & Edmonds,

2014). All participants were at the chronic stage of aphasia ( 9 months) and most had moderately

severe aphasia. Two participants had severe aphasia (Edmonds & Babb, 2011). Five participants

were diagnosed with anomic aphasia (all mild), 5 with conduction aphasia (one with substantial

jargon), 4 with transcortical motor aphasia, 2 with Brocas aphasia (both severe), and 1 with

Wernickes aphasia. The participants who received VNeST-C had moderate-severe Brocas aphasia

with mild to moderate apraxia of speech (AOS) and mild anomic aphasia with moderate-severe

AOS.

Overall, there has been replicated improvement and generalization of lexical retrieval

abilities in confrontation naming of nouns and verbs, sentence production and discourse, as well

as clinically significant improvement on the Western Aphasia Battery (WAB; Kertesz, 1982, 2006).

Further, significant improvement on reports of functional communication from family members

(on the Communicative Effectiveness Index [CETI; Lomas et al., 1989]) has been reported in 11

of 11 participants for whom we have those data. While every participant did not improve on all

outcome measures, all exhibited improvement and generalization to a number of outcome measures.

Thus, it is reasonable to suggest that VNeST may be appropriate for participants who generally

fit within the parameters of these participants. However, keep in mind the following: (a) We have

only tested one person with Wernickes aphasia (who also had a severe verb impairment). Her

improvement was encouraging, with improvements on the WAB, verb and noun naming, informative

and complete utterances in discourse, and the CETI (per her husbands ratings; Edmonds et al.,

2014); (b) We have excluded people with greater than mild to moderate AOS except in the

computerized VNeST study, where typing was included as part of the treatment. Even though

VNesST-C participants improved in spoken and written modalities, we cannot make generalized

clinical recommendations at this time; and (c) Diagnosis of global aphasia has also been an

exclusionary variable, because VNeST requires better comprehension than is often seen in persons

with global aphasia.

Dosage

In all VNeST studies, we have provided treatment 2 times/week for 1.52 hours per session

(though VNeST-C was delivered 3 times/week for 2 hours each session). In our most recent study,

we controlled dosage to 10 weeks of treatment with 10 verbs for approximately 3.5 hours of

treatment per week (35 hours total). The group of 11 participants exhibited improvement across

outcome measures (Edmonds et al., 2014) and examination of the slopes of improvement on

sentence probes administered throughout treatment revealed that participants did not plateau

79

Downloaded From: http://sig2perspectives.pubs.asha.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ashannsld/930947/ on 09/19/2017

Terms of Use: http://pubs.asha.org/ss/rights_and_permissions.aspx

Tutorial for Verb Network Strengthening Treatment (VNeST):

Detailed Description of the Treatment Protocol with

Corresponding Theoretical Rationale

Lisa A. Edmonds

Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders, Teachers College, Columbia University

New York, NY

Financial Disclosure: Lisa A. Edmonds is an Associate Professor at Columbia University.

Nonfinancial Disclosure: Lisa A. Edmonds has previously published in the subject area.

Abstract

Verb Network Strengthening Treatment (VNeST) is a theoretically motivated aphasia

treatment that has resulted in promising generalization to untrained sentences and

discourse in persons with aphasia. As with all speech and language therapies, it is critical

that clinicians understand the theoretical motivation behind VNeSTs protocol in order to

make informed decisions during provision of the treatment. This article provides a detailed

VNeST tutorial, including characteristics of participants who might be suitable, dosage

information, and detailed instructions for each treatment step, including rationale, cueing

guidelines, and frequently asked questions. Further guidance is provided regarding verb

selection, and a score sheet is included for easy recording of responses and cueing levels.

Aphasia is an acquired language disorder, primarily caused by stroke, which affects

language production and comprehension. Anomia, or difficulty retrieving words, is a pervasive

symptom of aphasia that can negatively impact basic communication functions such as interacting

with family and co-workers, talking on the phone, and expressing needs, wants, and emotions.

A fundamental challenge in aphasia treatment is to achieve improved lexical retrieval in sentences

and discourse, particularly for untrained words in untrained language contexts (i.e., generalization).

Verb Network Strengthening Treatment (VNeST) is a theoretically motivated aphasia treatment

that has resulted in promising generalization to sentences and discourse in persons with aphasia

(Edmonds & Babb, 2011; Edmonds, Nadeau, & Kiran, 2009; Edmonds, Mammino & Ojeda, 2014;

Furnas & Edmonds, 2014). There are a number of treatment steps in VNeST, and each has a

specific purpose with regard to the treatments theoretical foundation. Therefore, the purpose of

this article is to provide clinicians and researchers with a tutorial that details the logistics and

rationale of each treatment step. Suggestions regarding selection and development of treatment

and testing materials are also provided.

VNeST is based on theories of event memory that conceive of neurological networks of verbs

and related nouns (i.e., verb networks) that wire together through use and world knowledge (e.g.,

Ferretti, McRae, & Hatherell, 2001). The nouns related to the verbs in these proposed networks

are called thematic roles, because they relate to the verb with regards to who is performing the

action (agent), the receiver of the action (patient), the location of the action, and the instrument of

the action (e.g., The plumber [agent] is fixing [verb] the sink [patient] in the bathroom [location] with

a wrench [instrument]). Research has indicated that verbs and their related thematic roles are

neurally co-activated such that agents and patients prime/facilitate activation of related verbs

(Edmonds & Mizrahi, 2011; McRae, Hare, & Ferretti, 2005) and vice versa (Edmonds & Mizrahi,

2011; Ferretti, McRae, & Hatherell, 2001). There is also bidirectional neural co-activation between

verbs (e.g., slicing) and their instruments (e.g., knife) (Ferretti, McRae, & Hatherell, 2001; McRae

et al., 2005) and priming from locations (e.g., restaurant) to related verbs (e.g., eating; Ferretti

et al., 2001).

78

Downloaded From: http://sig2perspectives.pubs.asha.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ashannsld/930947/ on 09/19/2017

Terms of Use: http://pubs.asha.org/ss/rights_and_permissions.aspx

read the words, or read the words for them, as needed. Fade out reading assistance as they

improve. Once they choose the correct word, they can put it under the who or what card (see

Figure 1).

If the participant chooses a foil, (e.g., dentist) say, Lets think about what it means to drive.

Now lets think about a dentist. Is it a dentists job to drive? Typically, people will acknowledge the

problem. If the participant does not understand, then explain that driving involves going from one

place to another in a car or other vehicle. Then ask if that is what a dentist does for his/her job.

We do not discuss what the foil (dentist) does, as this involves training another verb and can cause

some confusion, especially if the participant is already having difficulty.

You can alternate between maximal and minimal cues. For example, a maximal cue might

be required for the first response for a verb, and that might generate ideas so that the participant

may only need minimal cues for the other pairs (or have independent responses). The goal is to

encourage independent responses but to provide sufficient support when needed. However, all cues

should require that the participant choose a correct response rather than being given a response.

Once an agent is chosen, request a corresponding patient (e.g., If they said soldier, the

patient might be tank). Participants are encouraged to provide at least one personal pair (e.g.,

dad/boat for drive), and responses can change from week to week. (Early VNeST studies requested

a list of agents or patients and then the corresponding noun, but it is more natural to generate one

scenario at a time). Elicitation of the corresponding noun is relatively easy for participants, since

the possibilities are constrained. Once it is established that, for example, the driver is a farmer,

then a patient like tractor, or pickup truck comes much easier. If the participant cannot retrieve a

patient independently, provide cues as described above. Once you have one pair, you will repeat

Step 1 until 3 to 4 pairs of words are generated.

To Keep in Mind During Step 1.

1. A verbs meaning is somewhat loose (relative to nouns) (Black and Chiat, 2003), and

the variability in meaning often reflects different thematic role combinations. Thus, it is

important to encourage participants to generate multiple pairs of agents and patients

(e.g., carpenter-lumber, chef-sugar, seamstress-fabric for measure) to comprehensively

activate a verbs multi-dimensional meaning (i.e., semantic representation). It may be

necessary to explicitly elicit variety in responses. For example, if the participant only

discusses family members, say something like You have mentioned a lot of family members,

which is great, but lets think of some other people who might drive, bake, etc. Then cue

as needed.

2. Make sure participants produce at least one personally relevant scenario to activate

their own memories and knowledge of a verb/event. For example, one participant said

that her husband (and she) could chop a banjo. This is a banjo-playing technique

that was relevant to her and would not have been clinician-generated, and it meant a

lot to her and her husband that she was able to express this idea independently.

Frequently Asked Questions about Step 1. Do I always have to start with the agent

(who)? No. In some cases asking for the patient first can be advantageous because some verbs

lend themselves to more patients, or the patients are easier to retrieve. For example, it is easily

understood that cars are driven. Once that is established as a patient, it is easy to prompt a

familiar agent by asking, Who in your family drives? or more specifically Who drove you here

today? Such adaptations are sometimes needed when participants are first learning the protocol

or for participants who have more challenging linguistic or cognitive limitations. Typically,

participants begin to understand the objective and will generate more diverse responses with less

cueing over time.

What if a participant has difficulty with maximal cueing? Maximal cueing can be adapted

by reducing the number of choices from four to two (one foil and one correct response). Further,

82

Downloaded From: http://sig2perspectives.pubs.asha.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ashannsld/930947/ on 09/19/2017

Terms of Use: http://pubs.asha.org/ss/rights_and_permissions.aspx

before 10 weeks. Thus, while there is potential variability regarding length of treatment, most

participants should show a reasonable amount of recovery by 10 weeks (see Edmonds and Babb,

2011 with severe participants).

Materials

Treatment Materials

VNeST was designed to be low tech, so that it could be administered in any setting. At

minimum, all that is needed is a pen and paper. However, materials can be prepared ahead of time

on cardstock (we cut index cards into thirds) for repeated use or use a clipboard-sized erasable

white board to write responses. The cards provide the benefit of being manipulable, but a whiteboard

or sheets of paper should work just as well.

There are a variety of verbs that can be used in treatment. One basic requirement is that

the verb is a two-place verb (takes 2 arguments; e.g., a subject and object; The waiter folds the

napkin.). Thus, one-place verbs, which only require one argument (e.g., The boy swims.) are not

recommended. However, our research has shown that training two-place verbs often results in

improvement to one-place verbs, so one-place verbs and/or sentence production can be evaluated

as a generalization measure. See Appendix A for suggestions on verb selection.

Outcome Measures

The outcome measures chosen to evaluate improvement should reflect a participants

treatment goals. Lexical retrieval abilities across a range of tasks, including confrontation naming

for nouns and verbs, sentence production, and discourse should be examined. You can also

evaluate aphasia severity (e.g., WAB-R), sentence comprehension, and functional communication.

The sentence probe pictures used in VNeST studies are not currently available. However, we have

also used the Northwestern Assessment of Verbs and Sentences (NAVS; Thompson, 2011) to

evaluate sentence production and comprehension as well as verb naming. The NAVS can be found

online (Flintbox, 2010). For noun naming, the Philadelphia Naming Test (PNT) is downloadable

free-of-charge online (Moss Rehabilitation Research Institute, 2013), complete with answer sheets

and scoring information. There are many ways to analyze discourse. One option is the stimuli

and analysis methods from Nicholas and Brookshire (1993), which can be found on the ASHA

website. In addition to the outcome variables described in Nicholas and Brookshire, we have

examined complete utterances, which consider both the completeness (contains a subject, verb,

and object [when required]) and relevance (relevant to the topic) of utterances (see Edmonds et al.,

2009; Edmonds et al., 2014). Evaluating the relative improvement of relevance and completeness

is also informative.

Treatment Protocol

See Appendix B for an example of a VNeST answer sheet.

Step 1. Generation of Multiple Scenarios Around the Trained Verb

Detailed Instructions. Set down the cards with the words who and what written on

them (see Figure 1). Point to each card and tell the participant that these cards say who and

what. Then place the card with the verb written on it between the who and what cards and

ask Who can/might (verb) something/someone? In this example, we will use the verb drive. If

the participant does not understand the word who, then you can say, Can you think of a person

who drives something? If the participant is able to independently produce a plausible response

(e.g., chauffeur, my wife, taxi drive), write the word on a blank card and set it under the who card

(see Figure 1).

80

Downloaded From: http://sig2perspectives.pubs.asha.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ashannsld/930947/ on 09/19/2017

Terms of Use: http://pubs.asha.org/ss/rights_and_permissions.aspx

Move on to the Next Verb

After completion of all steps for one verb, move to another verb. We train 10 verbs. Once we

train all 10 verbs, we cycle through them again. It is ideal to get through all 10 verbs in one week,

if possible.

Treatment Settings

VNeST has only been evaluated in outpatient sessions with trained clinicians. We have not

trained family members or volunteers to conduct VNeST; therefore, we do not have information

on how participants respond in these cases. Provision of VNeST requires an understanding of the

treatments principles, including feedback. Thus, if family members are trained to do VNeST, they

should be highly involved in treatment sessions with the clinicians first. The information in this

article may be helpful for home use/practice and training of volunteers or family members as well.

References

Black, M., & Chiat, S. (2003). Nounverb dissociations: A multi-faceted phenomenon. Journal of

Neurolinguistics, 16, 231250.

Edmonds, L. A., & Babb, M. (2011). Effect of Verb Network Strengthening Treatment in moderate-to-severe

aphasia. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 131145.

Edmonds, L. A., & Mizrahi, S. (2011). Online priming of verbs and thematic roles in younger and older

adults. Aphasiology, 25(12), 14881506.

Edmonds, L. A., Mammino, K., & Ojeda, J. (2014). Effect of Verb Network Strengthening Treatment (VNeST)

in persons with aphasia: Extension and replication of previous findings. American Journal of Speech

Language Pathology. doi:10.1044/2014_AJSLP-13-0098

Edmonds, L. A., Nadeau, S., & Kiran, S. (2009). Effect of Verb Network Strengthening Treatment (VNeST) on

lexical retrieval of content words in sentences in persons with aphasia. Aphasiology, 23(3), 402424.

Ferretti, T. R., McRae, K., & Hatherell, A. (2001). Integrating verbs, situation schemas, and thematic role

concepts. Journal of Memory and Language, 44, 516547.

Flintbox. (2010). Northwestern assessment of verbs and sentences (NAVS). Retrieved from https://flintbox.

com/public/project/9299/

Furnas, D. W., & Edmonds, L. A. (2014). The effect of Computer Verb Network Strengthening Treatment on

lexical retrieval in aphasia. Aphasiology, 28, 401420.

Kertesz, A. (1982). Western Aphasia Battery. Austin, TX: Pro-ed.

Kertesz, A. (2006). Western aphasia batteryRevised. Austin, TX: Pro-ed.

Lomas, J., Pickard, L., Bester, S., Elbard, H., Finlayson, A., & Zoghaib, C. (1989). The communicative

effectiveness index: Development and psychometric evaluation of a functional communication measure for

adults aphasia. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 54, 113124.

McRae, K., Hare, E., & Ferretti, T. R. (2005). A basis for generating expectancies for verbs from nouns.

Memory and Cognition, 33(7), 11741184.

Moss Rehabilitation Research Institute. (2013). Philadelphia naming test (PNT). Retrieved from http://www.

mrri.org/philadelphia-naming-test

Nicholas, L. E., & Brookshire, R. H. (1993). A system for quantifying the informativeness and efficiency of the

connected speech of adults with aphasia. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 36, 338350.

Rogalski, Y., Edmonds, L. A., Daly, V. R., & Gardner, M. J. (2013). Attentive Reading and Constrained

Summarization (ARCS) discourse treatment for anomia in two women with moderate-severe Wernickes type

aphasia. Aphasiology, 27, 12321251.

Thompson, C. K. (2011). The Argument Structure Production Test/The Northwestern Assessment of Verbs and

Sentences. Northwestern University.

Webster, J., Franklin, S., & Howard, D. (2004). Investigating the sub-processes involved in the production of

thematic structure: An analysis of four people with aphasia. Aphasiology, 18, 4768.

86

Downloaded From: http://sig2perspectives.pubs.asha.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ashannsld/930947/ on 09/19/2017

Terms of Use: http://pubs.asha.org/ss/rights_and_permissions.aspx

read the words, or read the words for them, as needed. Fade out reading assistance as they

improve. Once they choose the correct word, they can put it under the who or what card (see

Figure 1).

If the participant chooses a foil, (e.g., dentist) say, Lets think about what it means to drive.

Now lets think about a dentist. Is it a dentists job to drive? Typically, people will acknowledge the

problem. If the participant does not understand, then explain that driving involves going from one

place to another in a car or other vehicle. Then ask if that is what a dentist does for his/her job.

We do not discuss what the foil (dentist) does, as this involves training another verb and can cause

some confusion, especially if the participant is already having difficulty.

You can alternate between maximal and minimal cues. For example, a maximal cue might

be required for the first response for a verb, and that might generate ideas so that the participant

may only need minimal cues for the other pairs (or have independent responses). The goal is to

encourage independent responses but to provide sufficient support when needed. However, all cues

should require that the participant choose a correct response rather than being given a response.

Once an agent is chosen, request a corresponding patient (e.g., If they said soldier, the

patient might be tank). Participants are encouraged to provide at least one personal pair (e.g.,

dad/boat for drive), and responses can change from week to week. (Early VNeST studies requested

a list of agents or patients and then the corresponding noun, but it is more natural to generate one

scenario at a time). Elicitation of the corresponding noun is relatively easy for participants, since

the possibilities are constrained. Once it is established that, for example, the driver is a farmer,

then a patient like tractor, or pickup truck comes much easier. If the participant cannot retrieve a

patient independently, provide cues as described above. Once you have one pair, you will repeat

Step 1 until 3 to 4 pairs of words are generated.

To Keep in Mind During Step 1.

1. A verbs meaning is somewhat loose (relative to nouns) (Black and Chiat, 2003), and

the variability in meaning often reflects different thematic role combinations. Thus, it is

important to encourage participants to generate multiple pairs of agents and patients

(e.g., carpenter-lumber, chef-sugar, seamstress-fabric for measure) to comprehensively

activate a verbs multi-dimensional meaning (i.e., semantic representation). It may be

necessary to explicitly elicit variety in responses. For example, if the participant only

discusses family members, say something like You have mentioned a lot of family members,

which is great, but lets think of some other people who might drive, bake, etc. Then cue

as needed.

2. Make sure participants produce at least one personally relevant scenario to activate

their own memories and knowledge of a verb/event. For example, one participant said

that her husband (and she) could chop a banjo. This is a banjo-playing technique

that was relevant to her and would not have been clinician-generated, and it meant a

lot to her and her husband that she was able to express this idea independently.

Frequently Asked Questions about Step 1. Do I always have to start with the agent

(who)? No. In some cases asking for the patient first can be advantageous because some verbs

lend themselves to more patients, or the patients are easier to retrieve. For example, it is easily

understood that cars are driven. Once that is established as a patient, it is easy to prompt a

familiar agent by asking, Who in your family drives? or more specifically Who drove you here

today? Such adaptations are sometimes needed when participants are first learning the protocol

or for participants who have more challenging linguistic or cognitive limitations. Typically,

participants begin to understand the objective and will generate more diverse responses with less

cueing over time.

What if a participant has difficulty with maximal cueing? Maximal cueing can be adapted

by reducing the number of choices from four to two (one foil and one correct response). Further,

82

Downloaded From: http://sig2perspectives.pubs.asha.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ashannsld/930947/ on 09/19/2017

Terms of Use: http://pubs.asha.org/ss/rights_and_permissions.aspx

making the foil as obviously correct as possible will promote learning and success (e.g., Does your

husband drive? or Does a cat drive?). Over time foils can be added and diversified.

Can the participant write the responses on the cards rather than the clinician? Yes. We have

included writing for a number of participants. Participant 2 in Edmonds and Babb (2011) had

severely impaired spoken output, but her written output was notably better. Thus, we required her

to try to say her response first, and if it was not understood by the clinician (due largely to neologistic

output), then she wrote her response on a card. After she wrote it, she read it aloud (with assistance,

if needed). She improved in both spoken and written output (see Edmonds & Babb, 2011). With

computerized VNeST, participants spoke and then typed their responses. Both participants had

AOS, so working on speech and typing was motivational and functional, and both participants

showed improvements across modalities (see Furnas & Edmonds, 2014). Overall, including writing

during this step is motivating and engages multiple modalities. However, if the primary goal is

improved spoken output, then writing should come after the spoken response. Additionally, feedback

regarding the written output should not distract from the goals of Step 1 (semantic engagement

and lexical retrieval), unless writing is a primary goal. Thus, if spelling errors are made, simply

provide a written model of the word and allow the participant to copy it correctly rather than engaging

in detailed spelling training (e.g., phoneme to grapheme correspondence).

Can I provide phonemic cues to help participants produce a response ( e.g., Someone can

bake coo____ to elicit cookies?)? We have not provided phonemic cues in treatment, because we

want to maximally engage the semantic system during cueing.

What if someone makes a phonological error in their response? We do not address minor

errors or distortions that do not interfere with comprehension of a response. However, if a response

contains more problematic errors or is frustrating to the participant, we model the word and allow

up to three repetitions. For our research purposes, we never give visual, tactile, or other types of

cues. In a clinical setting, therapists should use their own judgment regarding the needs of their

participants.

Can I use pictures and ask questions about the picture rather than having the participant

generate words? This is not encouraged. Using pictures changes the underlying premise of VNeST.

Also, it may promote learning or association of correct responses rather than engaging semantic

searches to generate diverse scenarios. However, we have noticed self-monitoring limitations in

some participants that seem to limit generalization of increased lexical retrieval abilities to sentence

or discourse contexts (Edmonds et al., in preparation). Thus, it may be useful to introduce picture

description tasks (or other types of production tasks) to provide participants with opportunities to

monitor for pronoun usage, light verbs (e.g., do, make) or general terms (e.g., thing, stuff) in order to

replace such words with more specific terms(see Rogalski, Edmonds, Daly, & Gardner, 2013) for

more details about this approach). Since we have not conducted research on a self-monitoring

phase of VNeST, we cannot make specific recommendations as to how it would be integrated.

However, in most cases it would make sense to do this once lexical retrieval abilities have improved

with VNeST. Also, it would be important to use different pictures or tasks, so that participants do

not learn rote responses.

Step 2. The Participant Reads the Rriads Aloud (e.g., chef-chop-onion)

Detailed Instructions. The instructions for this step are fairly straight-forward. The

participant is instructed to read each agent-verb-patient triad aloud. Move the card with the verb

on it down for each triad, so that the words form a subject-verb-object order (e.g., dad-drive-boat,

chauffeur-drive-limousine). If the participant cannot read independently, do choral reading (read

together) or have the participant repeat each word. Point to each word during choral reading or

repetition. Typically participants improve in oral reading, so fade out cues as appropriate.

Objectives of Step 2. Step 1 promoted activation and retrieval of the individual words that

compose each scenario. Step 2 consolidates the scenarios and units through oral reading. This

83

Downloaded From: http://sig2perspectives.pubs.asha.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ashannsld/930947/ on 09/19/2017

Terms of Use: http://pubs.asha.org/ss/rights_and_permissions.aspx

step also reinforces basic canonical subject-verb-object word order, which may be helpful for

participants who have difficulty with basic sentence frame construction.

Frequently Asked Questions for Step 2

Should I require morphology and function words when they are reading the scenarios?

We do not require morphology, inflection or function words (e.g., The chef is chopping the onion.).

However, we do not discourage it if participants include it naturally. We do not train or focus on

morphology/functors because the goal of VNeST is to promote sufficient activation and lexical

retrieval of content words for inclusion in a sentence, and focusing on morphology/functors

(especially for persons with agrammatic aphasia) can detract attention from content words. However,

participants with relatively good sentence construction abilities at pre-treatment tend to include

some or all of the morphology and functor words in sentences during this step as they improve in

retrieval of content words.

Step 3

The participant chooses one scenario that he/she generated in Step 1 and answers three

wh-questions about it (where, when, why).

Detailed Instructions. Ask the participant to choose one scenario that he/she would

like to discuss in more detail. There are no restrictions about which they choose, though it is

recommended to encourage choosing different scenarios from week to week. Move the cards that

correspond to the scenario that the participant has chosen away from the other responses. Then

lay the where, why, and when cards down one at a time, and with each one, ask the corresponding

wh-question (e.g., Where does your dad drive a boat? Then, Why does your dad drive a boat in

the bay behind your house? and, When does your dad drive a boat in the bay behind your house to

relax?; see Figure 1). Asking questions in this way reinforces that each response should relate

logically to the whole scenario being developed. We have found that the best order of presentation

is where, why, and, when, because location is usually the easiest for participants to retrieve, and

it constrains the event so participants can logically provide a reason (why) and time (when) for

the event. The purpose of this step is to more comprehensively engage semantic, world and/or

autobiographical knowledge around the event scenarios. Thus, the focus is on plausibility of

responses rather than syntactic correctness.

If the participant has difficulty understanding the wh-questions, then clarify the meaning:

(a) Where does your dad drive a boat? What is the location or place? (b) Why does your dad drive

a boat? What is the purpose? (c) When does your dad drive a boat? Is it on a certain day, during a

certain season, at a certain time of day (morning, afternoon, night)?

Because there are various reasons participants may have difficulty with this step (e.g.,

comprehension issues, trouble with word retrieval, etc.), cue as needed to address the difficulty.

For example, if a person has trouble understanding where, then you could provide a forced choice

with a plausible and implausible option (e.g., Does your dad drive a boat in a lake or on a football

field?) It is our experience that even participants with relatively poor comprehension of wh-questions

at the beginning of treatment will improve appreciably on comprehension. Also, sometimes

responses to the why question can be overly general or repeated for every verb. If time allows (and

if it is appropriate for your participant, as this is a fairly sophisticated distinction), try to connect

the reason for the action to the action in a more specific way (e.g., if a participant says a chef slices

tomatoes for a sandwich because it his job, then you can reinforce that this is true. Then you ask,

But why do we slice a tomato for a sandwich? Why not just put a whole tomato on the sandwich

and eat it? This distinction is typically very helpful).

Once the responses have been laid down, the participant should read them aloud. The

responses in Figure 1 would be read as follows: Dad drive boat in the bay by our house to relax

on Saturdays. Provide reading cues as needed (see Step 2). Also, similar to Step 2, inclusion

of morphology/verb inflections is not required, though some participants do include it.

84

Downloaded From: http://sig2perspectives.pubs.asha.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ashannsld/930947/ on 09/19/2017

Terms of Use: http://pubs.asha.org/ss/rights_and_permissions.aspx

Table 2. Examples of Goals Typically Linked to Impairment-Focused Assessments.

Assessment Example of Typically Linked Goal ASHA NOMS Levels

Data

Spoken Improve ability to match single, personally Initial: Level 1 (unable to follow simple

Language relevant spoken words to pictures from directions, even with cues)

Comprehension: 45% accuracy to 90% accuracy in an array

of four pictures.

Word-Picture Goal: Level 2 (able to respond to simple

Matching = 45% words or phrases relevant to personal

needs given consistent, maximal cues)

Sentence-Picture

Matching = 0%

Reading: Improve ability to match single, personally Initial: Level 1 (attends to written words)

relevant written words to pictures from

45% accuracy to 90% accuracy in an array

of four pictures.

Written Word- Goal: Level 2 (able to read common

Picture words given consistent, maximal cues)

Matching = 45%

Goals that map very clearly and specifically to the evaluation data are encouraged and

even required by most rehabilitation companies and facilities within their documentation systems

to facilitate reimbursement. Undeniably, the links between the initial evaluation data to the goal

and desired outcomes in Table 2 are straightforward, and because of their clarity and obvious

measurement, they are likely to be reimbursed.

Will these goals affect Mrs. Cs participation in life? Although initial performance on

impairment-focused assessments, like standardized aphasia batteries, may be related to activity

participation, change on impairment-based assessments is not necessarily related to change on

activity participation (Ross & Wertz, 1999, 2002). So, focusing our intervention on a specific

impairment, like impaired auditory comprehension, does not necessarily mean that the client will

now be equipped to participate in life activities.

If we want to increase the likelihood that we will facilitate life participation in our clients,

we have to assess current opportunities for improved participation and focus our intervention

efforts on those. Lets use Mrs. Cs performance on the Communication Activities of Daily Living

(CADL-2; Holland, Frattali, & Fromm, 1999) as an example. This assessment uses role play to

sample a number of activities that are likely to be relevant to a person with aphasia residing in

the community, such as shopping, going to a doctors appointment, ordering from a restaurant

menu, understanding a bus schedule, and filling out forms. The CADL-2 overall score for Mrs. C

was 17%. Since points on most items of the CADL-2 are given based on producing a fully

communicative message regardless of modality, her overall score tells us that Mrs. C is not able

to use many communication modalities very effectively to perform in these role-play activities.

We can analyze specific items within the CADL-2 that correspond to specific activities as

an informal way to track communicative performance. For example, we can analyze Mrs. Cs

ability to provide personal information such as name, address, and medical information with

items #36 of the CADL-2. Assuming that providing personal information is a valuable activity for

Mrs. C, then this can be targeted with a treatment goal. ASHA NOMS levels can be assigned

based on the likelihood that Mrs. C will use spoken language expression or writing to convey the

personal information. Possible goals derived from activities assessed on the CADL-2 are shown in

Table 3.

91

Downloaded From: http://sig2perspectives.pubs.asha.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ashannsld/930947/ on 09/19/2017

Terms of Use: http://pubs.asha.org/ss/rights_and_permissions.aspx

Move on to the Next Verb

After completion of all steps for one verb, move to another verb. We train 10 verbs. Once we

train all 10 verbs, we cycle through them again. It is ideal to get through all 10 verbs in one week,

if possible.

Treatment Settings

VNeST has only been evaluated in outpatient sessions with trained clinicians. We have not

trained family members or volunteers to conduct VNeST; therefore, we do not have information

on how participants respond in these cases. Provision of VNeST requires an understanding of the

treatments principles, including feedback. Thus, if family members are trained to do VNeST, they

should be highly involved in treatment sessions with the clinicians first. The information in this

article may be helpful for home use/practice and training of volunteers or family members as well.

References

Black, M., & Chiat, S. (2003). Nounverb dissociations: A multi-faceted phenomenon. Journal of

Neurolinguistics, 16, 231250.

Edmonds, L. A., & Babb, M. (2011). Effect of Verb Network Strengthening Treatment in moderate-to-severe

aphasia. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 131145.

Edmonds, L. A., & Mizrahi, S. (2011). Online priming of verbs and thematic roles in younger and older

adults. Aphasiology, 25(12), 14881506.

Edmonds, L. A., Mammino, K., & Ojeda, J. (2014). Effect of Verb Network Strengthening Treatment (VNeST)

in persons with aphasia: Extension and replication of previous findings. American Journal of Speech

Language Pathology. doi:10.1044/2014_AJSLP-13-0098

Edmonds, L. A., Nadeau, S., & Kiran, S. (2009). Effect of Verb Network Strengthening Treatment (VNeST) on

lexical retrieval of content words in sentences in persons with aphasia. Aphasiology, 23(3), 402424.

Ferretti, T. R., McRae, K., & Hatherell, A. (2001). Integrating verbs, situation schemas, and thematic role

concepts. Journal of Memory and Language, 44, 516547.

Flintbox. (2010). Northwestern assessment of verbs and sentences (NAVS). Retrieved from https://flintbox.

com/public/project/9299/

Furnas, D. W., & Edmonds, L. A. (2014). The effect of Computer Verb Network Strengthening Treatment on

lexical retrieval in aphasia. Aphasiology, 28, 401420.

Kertesz, A. (1982). Western Aphasia Battery. Austin, TX: Pro-ed.

Kertesz, A. (2006). Western aphasia batteryRevised. Austin, TX: Pro-ed.

Lomas, J., Pickard, L., Bester, S., Elbard, H., Finlayson, A., & Zoghaib, C. (1989). The communicative

effectiveness index: Development and psychometric evaluation of a functional communication measure for

adults aphasia. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 54, 113124.

McRae, K., Hare, E., & Ferretti, T. R. (2005). A basis for generating expectancies for verbs from nouns.

Memory and Cognition, 33(7), 11741184.

Moss Rehabilitation Research Institute. (2013). Philadelphia naming test (PNT). Retrieved from http://www.

mrri.org/philadelphia-naming-test

Nicholas, L. E., & Brookshire, R. H. (1993). A system for quantifying the informativeness and efficiency of the

connected speech of adults with aphasia. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 36, 338350.

Rogalski, Y., Edmonds, L. A., Daly, V. R., & Gardner, M. J. (2013). Attentive Reading and Constrained

Summarization (ARCS) discourse treatment for anomia in two women with moderate-severe Wernickes type

aphasia. Aphasiology, 27, 12321251.

Thompson, C. K. (2011). The Argument Structure Production Test/The Northwestern Assessment of Verbs and

Sentences. Northwestern University.

Webster, J., Franklin, S., & Howard, D. (2004). Investigating the sub-processes involved in the production of

thematic structure: An analysis of four people with aphasia. Aphasiology, 18, 4768.

86

Downloaded From: http://sig2perspectives.pubs.asha.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ashannsld/930947/ on 09/19/2017

Terms of Use: http://pubs.asha.org/ss/rights_and_permissions.aspx

Appendix A. Suggestions for Choosing Verbs to Use in Treatment

Suggestions for Choosing Verbs to Use in Treatment

1. Choose a variety of verbs that represent different types of actions. You can choose verbs together with

your participant. Just make sure you get a range of verbs.

Example: Chop, Kick, Deliver, Measure, Read, Erase, Watch, Fry, Stir, Sew

2. Avoid training verbs that are highly related or associated to avoid semantic interference.

Example: Chop/slice, Kick/throw, Stir/Shake

3. Generalization to (improvement of) untrained semantically related verbs (and nouns) is hypothesized

(and has been seen across VNeST studies), so you can evaluate potential improvement of related

verbs as generalization measures. The verb pairs and triads below are examples of semantically

related/associated verbs. The related word(s) are indicated by the arrow symbol ()) (so only one verb

in a pair/triad would need to be treated). This is not a comprehensive list of possibilities.

Example: ChopSlice, KickThrow, MeasureWeigh, ReadWrite, EraseScrub,

WatchExamine, FryBoilBake, StirShake, SewKnitCrochet, DeliverSend,

PushPull, PaintDraw

4. You can choose verbs that relate to a specific area of interest/functionality for the participant (e.g.,

cooking, sports), but it is recommended that you elicit a variety of scenarios about each verb beyond

the specific area of interest (to promote generalization). The example below shows how a verb like

watch and throw, which relate to activities surrounding a participants interest in a local football

team can be broadened to include more diverse language (Only Step 1 examples shown, not all

necessarily retrieved during one session).

VERB: Watch

Buckeye fan watch- football game/highlights

Coach watch tapes (from game)

Referees watch instant replay

Babysitter watch child/son/daughter

My wife and I watch sunset

Audience watch movie

VERB: Throw

Quarterback throw pass/hail Mary/football

Pitcher throw knuckle ball

Olympian throw javelin/shotput

Comedian throw pie

Baby throw tantrum

My son throw Frisbee (at beach)

5. Do not be afraid to try different verbs. In general, verbs should 1) require a subject and object and 2)

promote some diversity of responses (though verbs differ in this regard).

87

Downloaded From: http://sig2perspectives.pubs.asha.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ashannsld/930947/ on 09/19/2017

Terms of Use: http://pubs.asha.org/ss/rights_and_permissions.aspx

Appendix B. Sample Response Sheet to Use for Recording Responses

and Cueing Levels

Copy the answer sheet below and enlarge it to 8 11. Use one sheet per verb.

88

Downloaded From: http://sig2perspectives.pubs.asha.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ashannsld/930947/ on 09/19/2017

Terms of Use: http://pubs.asha.org/ss/rights_and_permissions.aspx

Facilitating Life Participation in Severe Aphasia with Limited

Treatment Time1

Jacqueline Hinckley

Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders, University of South Florida

Petersburg, FL

Financial Disclosure: Jacqueline Hinckley is Associate Professor Emeritus at the University of

South Florida.

Nonfinancial Disclosure: Jacqueline Hinckley has previously published in the subject area.

Abstract

Although the recovery course of severe aphasia is typically much lengthier and more

protracted than other forms of aphasia, availability of treatment time is often quite limited.

Focusing on one or more specific language domains, such as auditory comprehension, may

be indicated. When treatment time is limited, however, progress in an impairment-focused

approach may be insufficient to affect the individuals daily life. This paper provides a

process for selecting a daily activity, targeting that activity in a participation-focused

intervention, and measuring progress when treatment time is limited. Case examples

illustrate the process. A focus on even one activity that occurs daily can provide ongoing

opportunities for practice and interaction in spite of ongoing treatment.

Perhaps as many as 29% of individuals experiencing left hemisphere stroke and aphasia

experience severe or global aphasia, at least initially (Kang et al., 2010). Since aphasia can be

part of other medical diagnoses and diseases, it is not unusual for clinicians working in medical

settings to be faced with the challenge of selecting appropriate assessments and treatment for

someone with severe aphasia.

The course of severe aphasia can be much more protracted than the recovery patterns of

individuals with less severe aphasia. Published studies of individuals with severe aphasia suggest

that comprehension and repetition may improve the most during the first year after onset, but

that continuous improvement in all other language modalities including spoken language can

occur over many years (e.g., Bakheit, Shaw, Carrington, & Griffiths, 2007; Smania et al., 2010;

Stark & Pons, 2007). Other anecdotal reports suggest that the period of more rapid improvement

is also delayed, perhaps between 6 and 18 months, rather than during the first few months post

onset.

A Rationale for a Focus on Life Participation in Severe Aphasia

Most individuals with severe aphasia will not have access to the kind of long-term services

that have been associated with significant long-term improvement in severe aphasia (Smania

et al., 2010; Stark & Pons, 2007). Also, perceived quality of life and social functioning are

significantly more restricted among those with severe aphasia than those without aphasia or with

other forms of aphasia (Hilari, Needle, & Harrison, 2012; Hilari & Byng, 2009). The critical

question, then, is how to best use the limited treatment resources that are available to make a

potentially long-term impact.

An approach to treatment that is exclusively impairment-focused may not be the most

efficient way of maximizing very limited treatment time. Take, for example, a treatment emphasis

on auditory comprehension, which is often a needed area of improvement in severe aphasia. An

1

Content in this article was presented as part of a SIG 2 Invited Seminar at the ASHA

Convention, Chicago, 2013.

89

Downloaded From: http://sig2perspectives.pubs.asha.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ashannsld/930947/ on 09/19/2017

Terms of Use: http://pubs.asha.org/ss/rights_and_permissions.aspx

exclusively impairment-focused approach might narrow treatment efforts on tasks that isolate

auditory comprehension performance in an easily measurable way. Tasks such as matching

spoken words to pictures or following commands have often been used to determine how well

someone understands spoken language. This approach to treatment is likely to require a more

extensive number of treatment sessions in order to achieve a generalizable effect across contexts

in one particular language domain, such as auditory comprehension.

An immediate focus on participating in an activity that is personally relevant and will be

used on a daily basis is one way of widening the impact of our treatment time. Selecting an

activity that the client is already doing routinely, or could easily be helped to do daily, will build

in additional communication practice. It can also facilitate well-being and overall activity level by

immediately providing a successful and enjoyable task that occurs frequently.

For example, an intervention that focused on a particular activity, in this case ordering

clothing from a catalog, was administered in either a non-intensive (4 hours per week) or

intensive (2022 hours per week) treatment schedule to individuals with moderately-severe

aphasia. Accurate and durable performance on the targeted activity (ordering from a catalog) and

transfer to similar activities or contexts that utilized similar strategies (such as ordering pizza)

was achieved in 110 hours of treatment. This evidence suggests that a focus on a particular

activity can produce equally successful results when treatment time is limited as it does with

more treatment time (Hinckley & Carr, 2005; Hopper & Holland, 1998).

Emphasizing Life Participation in the Evaluation

Treatment goals and outcomes are linked to our initial evaluation, so our selection of

assessments tends to drive documented goals and treatment selection. Initial evaluation data

that are focused on modality-specific performance are more likely to lead to goals and treatments

that are impairment-focused. Initial evaluation data that are focused on life participation will

more readily be translatable to life participation-focused goals and intervention.

For example, take the assessment data for Mrs. C, shown in Table 1. Mrs. Cs ability to

match spoken single words with pictures was moderately impaired, and she was completely

unable to match auditory sentences to pictures. Reading comprehension was similarly impaired,

and she was unable to name a single picture in a naming task. Table 2 shows typical goals that

might be derived from these kinds of evaluation data.

Table 1. Assessment Data for Mrs. C, a Person With Severe Aphasia

Assessment Score

Spoken Word-Picture Matching 45%

Written Word-Picture Matching 45%

Sentence-Picture Matching 0%

Spoken Picture Naming 0%

Communicative Abilities in Daily Living2 17%

90

Downloaded From: http://sig2perspectives.pubs.asha.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ashannsld/930947/ on 09/19/2017

Terms of Use: http://pubs.asha.org/ss/rights_and_permissions.aspx

Table 2. Examples of Goals Typically Linked to Impairment-Focused Assessments.

Assessment Example of Typically Linked Goal ASHA NOMS Levels

Data

Spoken Improve ability to match single, personally Initial: Level 1 (unable to follow simple

Language relevant spoken words to pictures from directions, even with cues)

Comprehension: 45% accuracy to 90% accuracy in an array

of four pictures.

Word-Picture Goal: Level 2 (able to respond to simple

Matching = 45% words or phrases relevant to personal

needs given consistent, maximal cues)

Sentence-Picture

Matching = 0%

Reading: Improve ability to match single, personally Initial: Level 1 (attends to written words)

relevant written words to pictures from

45% accuracy to 90% accuracy in an array

of four pictures.

Written Word- Goal: Level 2 (able to read common

Picture words given consistent, maximal cues)

Matching = 45%

Goals that map very clearly and specifically to the evaluation data are encouraged and

even required by most rehabilitation companies and facilities within their documentation systems

to facilitate reimbursement. Undeniably, the links between the initial evaluation data to the goal

and desired outcomes in Table 2 are straightforward, and because of their clarity and obvious

measurement, they are likely to be reimbursed.

Will these goals affect Mrs. Cs participation in life? Although initial performance on

impairment-focused assessments, like standardized aphasia batteries, may be related to activity

participation, change on impairment-based assessments is not necessarily related to change on

activity participation (Ross & Wertz, 1999, 2002). So, focusing our intervention on a specific

impairment, like impaired auditory comprehension, does not necessarily mean that the client will

now be equipped to participate in life activities.

If we want to increase the likelihood that we will facilitate life participation in our clients,

we have to assess current opportunities for improved participation and focus our intervention

efforts on those. Lets use Mrs. Cs performance on the Communication Activities of Daily Living

(CADL-2; Holland, Frattali, & Fromm, 1999) as an example. This assessment uses role play to

sample a number of activities that are likely to be relevant to a person with aphasia residing in

the community, such as shopping, going to a doctors appointment, ordering from a restaurant

menu, understanding a bus schedule, and filling out forms. The CADL-2 overall score for Mrs. C

was 17%. Since points on most items of the CADL-2 are given based on producing a fully

communicative message regardless of modality, her overall score tells us that Mrs. C is not able

to use many communication modalities very effectively to perform in these role-play activities.

We can analyze specific items within the CADL-2 that correspond to specific activities as

an informal way to track communicative performance. For example, we can analyze Mrs. Cs

ability to provide personal information such as name, address, and medical information with

items #36 of the CADL-2. Assuming that providing personal information is a valuable activity for

Mrs. C, then this can be targeted with a treatment goal. ASHA NOMS levels can be assigned

based on the likelihood that Mrs. C will use spoken language expression or writing to convey the

personal information. Possible goals derived from activities assessed on the CADL-2 are shown in

Table 3.

91

Downloaded From: http://sig2perspectives.pubs.asha.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ashannsld/930947/ on 09/19/2017

Terms of Use: http://pubs.asha.org/ss/rights_and_permissions.aspx

Table 3. Examples of Goals Linked to Activity-Specific Assessments.

Sample CADL-2 Activity Example Goal

Performances

Providing personal Client will provide personal information using written information with

information, items #36 90% accuracy with minimal cues.

Using the phone, items Client will dial 911 and indicate emergency type with 90% accuracy given

4042, 44 minimal cues.

Shopping, items 3037 Client will identify written categories associated with shopping with 90%

accuracy with minimal cues.

A Patient-Centered Model of Assessment and Goal Selection

Application of a patient-centered model for assessment and goal selection can help us

foreground life goals in a more clinically efficient way (Leach, Fleming, & Haines, 2010). A

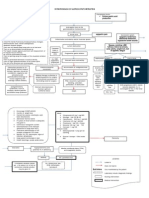

schematic of the process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. A Patient-Centered Model for Goal Selection.

Source. Adapted from Leach, E., Cornwell, P., Fleming, J., & Haines, T. (2010).

92

Downloaded From: http://sig2perspectives.pubs.asha.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ashannsld/930947/ on 09/19/2017

Terms of Use: http://pubs.asha.org/ss/rights_and_permissions.aspx

Maximizing Outcomes in Group Treatment of Aphasia:

Lessons Learned From a Community-Based Center

Darlene Williamson

Stroke Comeback Center

Vienna, VA

Department of Speech and Hearing Science, George Washington University

Washington, DC

Financial Disclosure: Darlene Williamson is the Founder and Director of the Stroke Comeback

Center and Adjunct Professor at George Washington University.

Nonfinancial Disclosure: Darlene Williamson has previously published in the subject area.

Abstract

Given the potential of long term intervention to positively influence speech/language and

psychosocial domains, a treatment protocol was developed at the Stroke Comeback Center

which addresses communication impairments arising from chronic aphasia. This article

presents the details of this program including the group purposes and principles, the use of

technology in groups, and the applicability of a group program across multiple treatment

settings.

In 2014, the stark reality of treatment for individuals with aphasia is that clinicians

are being asked to do more with less: less time and fewer dollars. This limitation in treatment

necessitates solutions that stretch dollars while providing efficacious treatment. As a result

aphasia communities are growing in popularity and in numbers (Simmons-Mackie & Holland,

2011). One such aphasia community is the Stroke Comeback Center in Vienna, VA founded to

provide long-term communication support operating within a Life Participation Approach to

Aphasia. Participants in this program are welcome to attend programs for as long as they feel they

are receiving benefit, which results in a community of stroke survivors dedicated to improving and

from whom much can be learned. This article shares information that has been learned through

involvement with over 300 participants at the center and which might reasonably be applied

across settings, including group purposes and principles and the use of technology that facilitates

improved communication.

Group Treatment for Individuals with Aphasia

Services for individuals with aphasia can be conducted successfully in groups, particularly

if consideration is given to some fundamentals of group treatment. The overall purpose of group

sessions must be specified. One purpose of group treatment is to provide an opportunity to

communicate with peers with structure and support. A successful group is structured around a

theme or language skill, using appropriate supports to facilitate conversation. An example of this

will be discussed later in the article. A second purpose of communication groups is to teach

specific communication strategies. Many communication strategies used in a group setting are

verbal strategies, but other modes of communication can and should be used (e.g., written cueing,

body language including gestures and facial expressions, even an assistive device). All are

appropriate and promote natural communication. A third purpose of a group is to provide an

opportunity to practice the strategies that any individual is using to facilitate communication. It

has been our experience that the real-life atmosphere of a group provides an appropriate and safe

venue for developing and effectively using individualized strategies. Lastly, a fourth purpose of

communication groups is to observe successful communication strategies being used by others in the

group. This may seem elementary, but the value of this peer modeling cannot be overemphasized.

100

Downloaded From: http://sig2perspectives.pubs.asha.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ashannsld/930947/ on 09/19/2017

Terms of Use: http://pubs.asha.org/ss/rights_and_permissions.aspx

Table 5. The Four Categories Included in the LIV with Examples of Activities in Each Category.

Category Examples of Activities

Home & Community Cleaning the house, doing laundry, grocery shopping, going to the doctor,

Activities voting

Creative & Relaxing Using a computer, bird watching, drawing/painting, listening to music,

Activities going to the movies

Physical Activities Golfing, yoga, walking, swimming, fishing

Social Activities Family gatherings, eating out, picnic, storytelling, using the phone

The purpose of the LIV questionnaire is to allow individuals with restricted

communication ability and their family members to indicate activities that are most relevant to

them. As each pictured activity is presented, the interviewer asks, Do you do this now? If the

client answers no, the follow-up question is do you want to start doing this? If the client is

already doing the activity, the follow-up question is do you want to do this more? (Haley,

Womack, Helm-Estabrooks, Lovette, & Goff, 2012).

Matching Formal Assessments to Valued Activities

Once the client and/or family have identified the most valued and important activities, the

clinician will need to complete an assessment that will contribute to the goal-setting process, help

the clinician select an effective treatment approach, and serve as an initial status from which to

measure progress. When treatment time is limited, the selection of the formal assessment tool

needs to be well thought out in order to ensure that some aspects of the assessment will link

directly to one or more of the valued activities. It will also be important to select a tool that will

reveal as many strengths as possible given the presence of severe aphasia.

Lets return to the case of Mrs. C, some of whose assessment data are shown in Table 1.

When Mrs. C completed the LIV card sort, she indicated that she very much wanted to participate

in dinner conversations with her family, but felt left out, probably due to both her impaired

auditory comprehension and her limited expressive abilities.

In order to assess initial abilities in conversation, plan intervention, and report

appropriate initial and final measures, the clinician will need to select formal and informal

measures that directly relate to conversational abilities. Among the assessments shown in

Table 1, matching spoken words to pictures is indirectly linked to the ability to understand

comprehension due to its decontextualized nature. Ability to match spoken words to pictures

does not reveal the clients ability to grasp conversation with all of its environmental,

paralinguistic, and nonverbal context. Only a conversational task will reveal and measure

conversational performance, taking into account all of the conversational supports for

comprehension and expression that will be available.

Two formal assessment tools will provide the clinician the opportunity to assess

conversationally-related abilities with a scoring system that can capture the use of various

communication modalities such as gesture, writing, or speech and are appropriate for those with

severe aphasia. The first of these is the CADL-2 assessment (Holland et al., 1999) described

earlier in this article. The second is the Boston Assessment of Severe Aphasia (BASA; Helm-

Estabrooks, Ramsberger, Morgan, & Nicholas, 1989). Both of these tools allow the clinician to

calculate a score that will capture potential changes in conversational abilities and the use of

conversational supports, such as use of gesture, writing, or a communication notebook. This will

give the clinician an opportunity to document change in the use of appropriate strategies and

their effect on the valued activity of the client, in this case, conversation.

Informal assessment can also be very important in this process. If at all possible, it would

be highly desirable to observe Mrs. C in a conversation with one of her family members to identify

94

Downloaded From: http://sig2perspectives.pubs.asha.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ashannsld/930947/ on 09/19/2017

Terms of Use: http://pubs.asha.org/ss/rights_and_permissions.aspx

potential strategies for Mrs. C and the family member, and to measure their use in successful

conversational interactions.

An example of an informal measure that can help the clinician observe and rate

conversational performance are the measures associated with Supported Conversation for Adults

with Aphasia (SCA), a training technique designed to teach individuals tools for enabling effective

conversation by those with severe aphasia (Kagan et al., 2004).

The Measure of Participation in Conversation (Kagan et al., 2004) is an example of a

rating scale that can be applied to those with severe aphasia for documenting conversational

participation. Two five-point rating scales are provided. Ratings on the Interaction scale range

from 0 (no attempt to participate in conversation) to 4 (takes responsibility for conversational

interaction). Ratings on the Transaction scale related to how well the person with aphasia can

exchange pieces of information. The transaction scale ranges from 0 (no evidence of being able to

understand or get a message across), to 4 (able to understand and get a message across). It is

important to note that ratings are not dependent on how the person with aphasia accomplishes

the communication, and any strategies, tools, or supports can be subsumed in the rating scale.

Although other ways to rate or measure participation in conversation exist, these tools were

specifically designed for those with severe aphasia. The case of Mr. L will illustrate assessment and

goal selection to facilitate life participation in severe aphasia according to the model shown in Figure 1.

Case Example

Mr. L was diagnosed with a global aphasia 2.5 months ago when he was hospitalized with

a left hemispheric stroke. During that time, he underwent inpatient rehabilitation that

culminated in his discharge to home with home health services. He has continued to make

physical improvements along with some small improvements in his communication. Because of

his physical improvements, he was referred to outpatient services for continued therapy.

At this particular outpatient facility, outpatient visits are encouraged to last for only

30 minutes, and are scheduled three times per week. It is anticipated that Mr. L will be able to

receive approximately one month of outpatient speech therapy based on his supplemental

insurance. So, a total of 12 sessions is anticipated.

Mr. L attends his first outpatient session with his wife, Mrs. L, with whom he lives. They are

both retired and prior to Mr. Ls stroke, enjoyed an active social life in their retirement community.

Determine the Clients Priorities

Knowing that there are as few as 12 sessions available for intervention, it is important to

incorporate the clients priorities as much as possible. During the LIV card sort, Mr. L selected

the restaurant picture as an important one. During the interview, Mrs. L stated that going out

with these friends was very important to them, and now her only time to go out socially.

Mr. and Mrs. L routinely go out to dinner two times a week with friends from church (one day

a week) and a group of neighbors (another day a week). Each group goes to different restaurants each

time, but there is a limited set of restaurants because of distance and group preferences

Mrs. L reported that, on the last few occasions when they went out to a restaurant, Mr. L

seemed to get very upset, pushing the menu away, and using obscenities when she tried to order

for him. She knows he is embarrassed or uncomfortable since he is unable to order for himself,

but she doesnt know how to handle the social situation.

Complete Formal and Informal Assessment

Language assessment data at the time of discharge from home health approximately

3 weeks prior to Mr. Ls first outpatient appointment is provided in Table 6. Although Mr. Ls ability

to match spoken or written words to pictures is relatively good, he still has substantial difficulty

understanding sentences. His expression is severely limited, and he is unable to name pictures.

95

Downloaded From: http://sig2perspectives.pubs.asha.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ashannsld/930947/ on 09/19/2017

Terms of Use: http://pubs.asha.org/ss/rights_and_permissions.aspx

Table 6. Assessment Data for Mr. L., a Person With Severe Aphasia.

Assessment Score