Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Official NASA Communication 01-120

Uploaded by

NASAdocumentsOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Official NASA Communication 01-120

Uploaded by

NASAdocumentsCopyright:

Available Formats

David E.

Steitz

Headquarters, Washington, DC June 14, 2001

(Phone: 202/358-1730)

Cynthia M. O'Carroll

Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD

(Phone: 301/614-5563)

Carolyn Bell

U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, VA

(Phone: 703/648-4463)

RELEASE: 01-120

MICROBES AND THE DUST THEY RIDE IN ON

MAY POSE HEALTH RISK

Potentially hazardous bacteria and fungi catch a free ride

across the Atlantic, courtesy of North African dust plumes.

NASA-funded researchers who made the discovery believe the

stowaway microbes might pose a health risk to people in the

western Atlantic region.

Dale Griffin, Virginia Garrison, and Eugene Shinn of the U.S.

Geological Survey (USGS) and Jay Herman of NASA's Goddard

Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD, outline their findings in

a paper titled "African Desert Dust in the Caribbean

Atmosphere: Microbiology and Public Health." The paper will be

published June 14 in the journal Aerobiologia.

"The National Institute of Health's National Institute of

Allergy and Infectious Diseases identifies airborne dust as

the primary source of allergic stress worldwide," stated

Shinn. "The identification of microbes in transported dust

is important as they may be a source of respiratory stress and

disease above and beyond that caused by exposure to

particulate matter."

African dust has produced red-tinged sunsets in south Florida

for years. The dust comes every year during northern Africa's

dry season, when storm activity in the Sahara Desert region

generates clouds of dust. The dust, originating from fine

particles in the arid topsoil, is transported into the

atmosphere by winds and may be carried more than 10,000 feet

high into the atmosphere by easterly trade winds. Typically,

it takes 5 to 7 days for the dust clouds to cross the Atlantic

Ocean and reach the Caribbean and Americas.

"The dust events are cyclical," Griffin said. "Studies by

other researchers have shown that from February to April, the

winds bring an estimated 280,000 tons per event to 13 million

tons per year to the Northeastern Amazon Basin. From June to

October the winds shift and typically bring dust to North and

Central America and the Caribbean."

During the peak of the dust season in July 2000, Garrison

collected samples of airborne pollutants and dust daily on the

island of St. John in the Virgin Islands and sent them to the

USGS laboratory in St. Petersburg, FL, for microbial analysis

by Griffin. He compared his results with satellite

observations tracking dust clouds from North Africa. The air

samples with high levels of microbes were collected on the

days that NASA's Total Ozone Mapping Spectrometer satellite

instrument observed the African dust sweeping into the region,

indicating that the microbes had been transported from Africa.

"In the week it takes for North African dust to cross the

Atlantic some of the microbes die because of exposure to

ultraviolet (UV) rays of the Sun," said Griffin. "However,

microbes in the cracks and crevasses of dust particles may be

shielded from UV. We also believe that the upper altitudes of

the dust clouds deflect harmful UV rays, shielding microbes at

lower altitudes as they are transported across the Atlantic

Ocean. Additionally, when dust clouds move over open water in

lower latitudes, the moderate temperatures and high humidity

are known to enhance microbial survival."

Florida receives more than 50 percent of all microbe-laden

African dust that reaches the United States. Over the last 25

years, dust quantities reaching Miami have increased during

periods of African drought. The U.S. Environmental Protection

Agency says these tiny dust particles can penetrate deep into

your airways and react with lung tissue. Herman said. "During

major dust episodes reaching Florida, there could be a

correlation with increased respiratory problems."

In addition to the dust itself, even small concentrations of

fungal spores can trigger allergic reactions. A study by M.E.

Howitt of the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Barbados documented

a 17-fold increase in asthma attacks in Barbados between 1973

and 1996, corresponding with the increase in African dust

transport to the region.

Fungi and bacteria that survive the trans-Atlantic journey in

dust include bacterial or fungal cultures that do not produce

disease mixed with species that do produce disease in both

humans and plants.

NASA's Earth Science Enterprise Environment and Health Program

at Goddard, a cooperative program with local, state, and

federal and international institutions funded this research.

The initiative uses NASA remote-sensing satellites and other

data to investigate the connections between the world's

environmental conditions and human health. More information

about this research and images can be found on the Internet

at:

http://www.gsfc.nasa.gov/gsfc/earth/toms/microbes.htm

http://coastal.er.usgs.gov/african_dust/

-end-

You might also like

- NASA: 190101main Plum Brook MapDocument1 pageNASA: 190101main Plum Brook MapNASAdocuments100% (2)

- NASA: 178801main Goals ObjectivesDocument12 pagesNASA: 178801main Goals ObjectivesNASAdocuments100% (2)

- NASA 122211main M-567 TKC JNLDocument1 pageNASA 122211main M-567 TKC JNLNASAdocumentsNo ratings yet

- NASA: 190101main Plum Brook MapDocument1 pageNASA: 190101main Plum Brook MapNASAdocuments100% (2)

- NASA 168206main CenterResumeDocument67 pagesNASA 168206main CenterResumeNASAdocumentsNo ratings yet

- NASA 149000main Nasa 2005 ReportDocument66 pagesNASA 149000main Nasa 2005 ReportNASAdocumentsNo ratings yet

- NASA 168207main ExecutiveSummaryBrochureDocument2 pagesNASA 168207main ExecutiveSummaryBrochureNASAdocumentsNo ratings yet

- NASA 149000main Nasa 2005 ReportDocument66 pagesNASA 149000main Nasa 2005 ReportNASAdocumentsNo ratings yet

- NASA: 55583main Vision Space Exploration2Document32 pagesNASA: 55583main Vision Space Exploration2NASAdocuments100% (5)

- NASA 168207main ExecutiveSummaryBrochureDocument2 pagesNASA 168207main ExecutiveSummaryBrochureNASAdocumentsNo ratings yet

- NASA 122211main M-567 TKC JNLDocument1 pageNASA 122211main M-567 TKC JNLNASAdocumentsNo ratings yet

- NASA: 55583main Vision Space Exploration2Document32 pagesNASA: 55583main Vision Space Exploration2NASAdocuments100% (5)

- NASA 168206main CenterResumeDocument67 pagesNASA 168206main CenterResumeNASAdocumentsNo ratings yet

- NASA: 178801main Goals ObjectivesDocument12 pagesNASA: 178801main Goals ObjectivesNASAdocuments100% (2)

- NASA 151450main FNL8-40738Document2 pagesNASA 151450main FNL8-40738NASAdocumentsNo ratings yet

- NASA: 68481main LAP-RevADocument20 pagesNASA: 68481main LAP-RevANASAdocumentsNo ratings yet

- NASA: 67453main Elv2003Document10 pagesNASA: 67453main Elv2003NASAdocumentsNo ratings yet

- NASA: 55583main Vision Space Exploration2Document32 pagesNASA: 55583main Vision Space Exploration2NASAdocuments100% (5)

- NASA 122211main M-567 TKC JNLDocument1 pageNASA 122211main M-567 TKC JNLNASAdocumentsNo ratings yet

- NASA: 55583main Vision Space Exploration2Document32 pagesNASA: 55583main Vision Space Exploration2NASAdocuments100% (5)

- NASA 166985main FS-2006-10-124-LaRCDocument35 pagesNASA 166985main FS-2006-10-124-LaRCNASAdocumentsNo ratings yet

- NASA 168207main ExecutiveSummaryBrochureDocument2 pagesNASA 168207main ExecutiveSummaryBrochureNASAdocumentsNo ratings yet

- NASA: 190101main Plum Brook MapDocument1 pageNASA: 190101main Plum Brook MapNASAdocuments100% (2)

- Language Assistance Plan (LAP) Accommodating Persons With Limited English Proficiency in NASA/KSC-Conducted Programs and ActivitiesDocument11 pagesLanguage Assistance Plan (LAP) Accommodating Persons With Limited English Proficiency in NASA/KSC-Conducted Programs and ActivitiesNASAdocumentsNo ratings yet

- NASA 171651main fs-2007-02-00041-sscDocument2 pagesNASA 171651main fs-2007-02-00041-sscNASAdocumentsNo ratings yet

- NASA: 188227main fs-2007-08-00046-sscDocument2 pagesNASA: 188227main fs-2007-08-00046-sscNASAdocumentsNo ratings yet

- NASA 149000main Nasa 2005 ReportDocument66 pagesNASA 149000main Nasa 2005 ReportNASAdocumentsNo ratings yet

- NASA 168206main CenterResumeDocument67 pagesNASA 168206main CenterResumeNASAdocumentsNo ratings yet

- NASA: 178801main Goals ObjectivesDocument12 pagesNASA: 178801main Goals ObjectivesNASAdocuments100% (2)

- NASA 174803main MSFC Prime ContractorsDocument10 pagesNASA 174803main MSFC Prime ContractorsNASAdocumentsNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Polygel CA MSDS guideDocument6 pagesPolygel CA MSDS guideBIONATURNo ratings yet

- Chlorine Industry ProfileDocument47 pagesChlorine Industry ProfileBrett RagonNo ratings yet

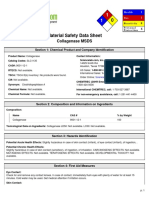

- Collagenase MSDSDocument5 pagesCollagenase MSDSRizky BagusNo ratings yet

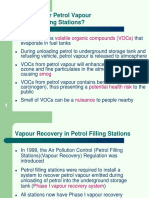

- Why Recover Petrol Vapour in Petrol Filling Stations?: Volatile Organic Compounds (Vocs)Document9 pagesWhy Recover Petrol Vapour in Petrol Filling Stations?: Volatile Organic Compounds (Vocs)sakthiNo ratings yet

- ENVR-S335 - U5 Air Pollution Dispersion and ModelingDocument60 pagesENVR-S335 - U5 Air Pollution Dispersion and ModelingPeter LeeNo ratings yet

- Greenhouse EffectDocument30 pagesGreenhouse EffectFernan SibugNo ratings yet

- Review of Literature of Air Pollution in MumbaiDocument6 pagesReview of Literature of Air Pollution in Mumbaipwvgqccnd100% (1)

- 30 Reduction in Energy by Cooler Modification With IKN Pendulum CoolerDocument26 pages30 Reduction in Energy by Cooler Modification With IKN Pendulum CoolerBülent BulutNo ratings yet

- Carbon RemoverDocument6 pagesCarbon RemoverdimasfebriantoNo ratings yet

- CopiersDocument3 pagesCopiersMabrouk Salem IssaNo ratings yet

- Acrylamide MSDSDocument6 pagesAcrylamide MSDSSatheesh KumarNo ratings yet

- GreenDocument55 pagesGreendurgas_1988No ratings yet

- Module 5: Environmental EducationDocument61 pagesModule 5: Environmental EducationChristlly LamyananNo ratings yet

- Pen - Udara Dalam RuangDocument26 pagesPen - Udara Dalam RuangFaradina Shefa AuliaNo ratings yet

- Air Quality Management PlanDocument22 pagesAir Quality Management PlanMohammed Al Mujaini100% (1)

- BDLI DLR WhitePaper German Aviation Research Zero Emission Aviation - en 2020Document67 pagesBDLI DLR WhitePaper German Aviation Research Zero Emission Aviation - en 2020Kang HsiehNo ratings yet

- Federal Register / Vol. 70, No. 203 / Friday, October 21, 2005 / Rules and RegulationsDocument1 pageFederal Register / Vol. 70, No. 203 / Friday, October 21, 2005 / Rules and RegulationsJustia.comNo ratings yet

- The Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974Document2 pagesThe Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974james harryNo ratings yet

- Schlumberger QHSE - Environment Level 1Document12 pagesSchlumberger QHSE - Environment Level 1Liza Nashielly Grande100% (2)

- Environmental Design For UrbanDocument347 pagesEnvironmental Design For UrbanAgisa Xhemalaj100% (2)

- KPWD 2019 - Ce 1 PDFDocument35 pagesKPWD 2019 - Ce 1 PDFmadhuri100% (3)

- EDITING Inglés 7° - Unit 4 Green Issues - Worksheet 1Document7 pagesEDITING Inglés 7° - Unit 4 Green Issues - Worksheet 1Anelis Del Carmen Leal ContrerasNo ratings yet

- United Chemicals Company: Cottage Air FreshenerDocument2 pagesUnited Chemicals Company: Cottage Air Freshenereng4008No ratings yet

- ACE Glo Spray FluorescentDocument15 pagesACE Glo Spray FluorescentIan Czar E. BangcongNo ratings yet

- Climate Change Adaptation and MitigationDocument39 pagesClimate Change Adaptation and Mitigationldrrm nagaNo ratings yet

- Amy-P: Safety Data SheetDocument14 pagesAmy-P: Safety Data SheetKadek Ayang Cendana PrahayuNo ratings yet

- LNG Shipping & Bunkering Nikhil MogheDocument8 pagesLNG Shipping & Bunkering Nikhil MoghepkkothariNo ratings yet

- Thesis Topics For Renewable EnergyDocument4 pagesThesis Topics For Renewable Energyheatherleeseattle100% (2)

- Air Pollution EpisodesDocument40 pagesAir Pollution Episodesjanice omadto100% (1)

- Air Quality Index and ExplanationDocument4 pagesAir Quality Index and ExplanationPrarthana DasNo ratings yet