Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Peplau

Uploaded by

basok buhariOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Peplau

Uploaded by

basok buhariCopyright:

Available Formats

UNJ Oct 2006-363.

ps 9/29/06 3:45 PM Page 363

Using Peplaus Theory of C

O

N

Interpersonal Relations to Guide T

I

The Education of Patients N

U

Undergoing Urinary Diversion I

N

G

Katherine Marchese

E

B

ladder cancer is the sec- Patients diagnosed with bladder cancer may require a urinary diver- D

ond most common uro- sion to maximize their health care outcomes. These patients, faced

logic cancer in the with sudden changes in their health status, develop complex unmet

U

United States resulting needs that can be addressed by a planned program of education. C

in over 61,000 new cases in 2006 Peplaus theory of interpersonal relations offers a framework for A

(American Cancer Society, 2006). patient teaching that emphasizes the importance of the nurse-patient

Approximately 30% of all new T

relationship. This therapeutic relationship enables the nurse to pro- I

cases present with muscle-inva-

sive disease that requires a radi- vide the patient with the information needed to understand the diag-

nosis, cooperate in the treatment plan, facilitate postoperative recov-

O

cal cystectomy and a urinary

diversion for the best cure rate. ery, and return to a state of independence with quality of life. N

Surgical options for a urinary

diversion include an ileal con- decreases, the patient and/or type of diversion created. The

duit diversion or the formation of family are required to assume orthotopic neobladder is re-

a continent urinary reservoir more responsibility for postoper- attached to the urethra so that the

(CUR) (Kane, 2000a; Perimenis & ative care at an earlier date. A patient urinates through the mea-

Koliopanou, 2004). The teaching well-planned, concise nursing tus (Gray & Beitz, 2005). A sec-

needs of persons with a surgical- intervention/teaching program is ond method of diversion, the

ly altered urinary tract system are necessary to facilitate the transi- continent cutaneous reservoir,

significant. Patients undergoing tion from hospital to home. The involves creating an efferent limb

this major abdominal surgery are purpose of this article is to show ending with a stoma that is

at risk for multiple postoperative how Hildegard Peplaus Theory brought through the abdomen to

complications including pneumo- of Interpersonal Relations can the skin level (Gray & Beitz,

nia, ileus, infections, throm- guide the nurses effort to pro- 2005; Kane, 2000a). Elimination

bophlebitis, and emboli. Further, vide critical teaching for these from the continent cutaneous

the potential for altered body patients. reservoir requires insertion of a

image, incontinence, and changes catheter into the reservoir to

in sexual functioning exist Overview of Continent drain the urine.

(Perimenis & Koliopanou, 2004). Urinary Reservoir Patients have significant pre

As the length of hospitalization Continent urinary reservoirs and postoperative needs that

reflect the state of the art unfold with the cancer diagnosis,

approach to urinary diversion. and balloon to affect daily life

Katherine Marchese, BSN, RN, APN,

CWOCN, CURN, is a Research Two types of CURs are construct- both pre-operatively and postop-

Coordinator, Womens Pelvic Medi- ed by isolating and detaching eratively. Physical needs include

cine Center, Loyola University Medical various sections of the intestine learning the management of the

Center, Maywood, IL. and configuring this tissue into a altered urinary system, receiving

sphere (Gray & Beitz, 2005; Kane, adequate pain control, and

Note: CE Objectives and Evaluation 2000a). This sphere-shaped re- understanding the role of nutri-

Form appear on page 371.

servoir is then anastomosed to tion in the recovery phase (Kane,

Note: The author reported no actual or the intact upper urinary tract sys- 2000b). A daily exercise plan

potential conflict of interest in relation to tem (Gray & Beitz, 2005). Eli- with increasing intensity and

this continuing nursing education article. mination of urine depends on the duration is necessary to maintain

UROLOGIC NURSING / October 2006 / Volume 26 Number 5 363

UNJ Oct 2006-364.ps 9/29/06 3:45 PM Page 364

C levels of activities of daily living, confront (Fleischer & Bryant, tion, and resolution. The nurse

O prevent constipation, and lessen 2005; Gray & Beitz, 2005). must adapt to different roles so

the possibility of pneumonia or Knowledge deficits about the diag- that the needs of the patient are

N emboli. If necessary, in-home nosis, surgical treatment options, met within each different phase

T physical therapy can be pre-operative testing procedures, (Forchuk, 1991; Peplau, 1997).

I arranged. and short and long-term postoper- Nursing roles include stranger,

Lack of proper nutrition can ative care, create an environment teacher, leader, surrogate, coun-

N delay the healing process and that further increases patients selor, and resource person

U increase the risk for other surgi- anger, grief, fear, and anxiety (Peplau, 1997).

I cal complications. Since nutri- (Fleischer & Bryant, 2005; Gray & Peplau (1997) suggests that

tion is a key component in the Beitz, 2005). Instruction by a as nurses learn to apply princi-

N recovery process, patients may knowledgeable nurse is, there- ples of human relationships, they

G need to re-evaluate previous eat- fore, critical to help guide them mature in the ability to promote

ing habits. Loss of appetite is through decision making, treat- therapeutic relationships as they

common following this surgery ment, and recovery in order to come to understand their own

E and these patients should be promote their return to optimal behaviors and needs. Successful

D encouraged to eat six small meals health status. Peplau (1992) iden- nurse-patient relationships require

U daily with attention to protein at tifies a need for patients to also unbiased, patient-focused encoun-

C each meal. Isolated patients or be part of a community. These ters that address and meet the

those living alone are less likely patients need involvement with patients needs (Peterson &

A to eat properly. Community friends and family on a social Bredow, 2004). Nurses must recog-

T resources such as Meals on level beyond their assistance as nize, accept, and encourage cues

I Wheels, well-being checks, and caregivers. Rejoining their church that indicate the patients readi-

clergy visits can be planned to community, meeting friends for ness for growth and movement.

O improve the needed social aspect lunch/dinner, and participating Likewise, they must be able to

N of eating. in other community events may identify and mobilize communi-

Social needs relate to con- prevent depression. ty resources to help patients cope

cerns about finances including with the psychosocial needs that

the loss of income, inability to Peplaus Theory of arise with sudden change in

pay for hospital services and Interpersonal Relations health status (Peterson & Bredow,

other medical costs, and the Peplaus (1992) theory of 2004).

inability to care for themselves or interpersonal relations provides

other dependant family mem- a conceptual framework by Phases of the Interpersonal

bers. Patients may also experi- which the nurse can assess, plan, Process

ence a change in their role or sta- and intervene for optimal out- Orientation. Peplau (1992)

tus within the family, going from comes for the patient with blad- outlines the phases of the inter-

decision maker to dependent der cancer. The foundation of her personal process that are integral

member. This may cause increased theory explores the primacy of for successful teaching including

stress, anxiety, and depression. the nurse-patient relationship orientation, identification, ex-

Compound this with the fact that, (Forchuk, 1991; Peplau, 1997). ploitation, and resolution (see

in the initial postoperative peri- According to Peplau (1992), the Table 1). In the orientation phase,

od, these patients usually require nurse is a complex individual, the nurse and patient meet. As

additional family support for who is the sum of all past experi- the patient begins to accept the

assistance with physical care and ences, rigorous nursing training, nurse and his/her level of exper-

temporary housing. Many are and unique personality traits. tise, the role advances from

elderly, live alone, and should The patient, also a complex indi- stranger to resource person and

not return to their primary home vidual, has a unique personality counselor (Peplau, 1992). The

alone for at least 1 week. Yet and is knowledgeable within his nurse answers questions and

many of these patients may be or her own frame of reference assesses the patients readiness to

reluctant to interrupt their chil- (Peplau, 1992). The nurse-patient learn. Once the patient acknowl-

drens lives and request assis- relationship is initiated with a edges and accepts his or her own

tance. If necessary, short-term change in the health status of the knowledge deficit, there is a

stays in extended care facilities patient, and the availability of a motivation to learn. This aware-

can be arranged through social nurse with the ability to provide ness and need permits the nurse

service agencies. specific skills (Peplau, 1992). to move into the roles of teacher

Psychological needs stem The nurse-patient relationship and resource person (Peplau,

from the physical and social evolves through the phases of ori- 1992). Limited information is

issues patients are challenged to entation, identification, exploita- given based on the stressors the

364 UROLOGIC NURSING / October 2006 / Volume 26 Number 5

UNJ Oct 2006-365.ps 9/29/06 3:45 PM Page 365

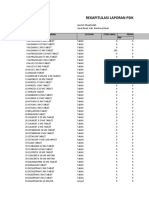

Table 1. C

Phases of the Interpersonal Process O

Phase of N

Interpersonal Teaching Activities for the Patient Undergoing T

Process Definition Urinary Diversion

I

Orientation Patient recognition of need for help. 1. Assessment of prior knowledge and N

Resources provided on limited basis as experiences.

acceptable by patient. 2. Assessment of readiness to learn. U

Initiation of nurse-patient relationship. 3. Involvement of patient in developing mutual I

teaching goals. N

4. Presentation of educational materials.

5. Discussion of pre-operative procedures. G

6. Different options for diversions; patient

pathways.

E

Identification Patient identifies problems to be worked 1. Demonstration/return demonstration of D

on. neo-bladder care.

The patient has some working knowledge a. Bladder irrigation. U

of the health care needs. b. Maintaining tube patency. C

Trust level with nurse is in early stages c. Care and cleaning of equipment.

and the patient will selectively begin d. Knowledge of emergency situations. A

to assimilate knowledge and accept 2. Discussion on nutrition. T

interactions with nurse. a. Re-assessment of prior eating habits;

Imitative behavior begins and gradually reduce empty calories. I

switches to a creative constructive b. Six small meals daily with attention to five O

response. food groups. N

c. Fluid requirement 2 quarts daily.

3. Development of activity plan.

a. Rationale for exercise.

b. Intensity and duration.

Exploitation Comfort and trust level established. 1. Reaffirm patients knowledge and expertise.

Patient takes advantage of services 2. Promote independence.

offered by nurse and benefits from 3. Identify available community resources.

relationship with nurse. 4. Role playing.

Some vacillation between dependence on 5. Present theoretical complex situations and

nurse and self-direction. have patient problem solve.

Focus on incorporating learned experi-

ences into future health status and

quality of life (QOL).

Resolution Prior goals have been met and new goals 1. Encourage participation in support group for

are formed. continent diversions.

Patient experiences a sense of security 2. Identify QOL issues and discuss options.

because needs have been met in a a. Nocturnal incontinence.

timely manner. b. Sexual changes.

Increase in self-reliance and decreased c. Alterations in body image.

reliance and identification with d. Anxiety about cancer diagnosis.

urologic nurse.

patient may be experiencing provided to the patient at any exhibited by the patient enables

such as pain, fear, anxiety, or one time (Pohl, 1978). Active the nurse to suggest ways to redi-

emotional instability (Peplau, participation, problem solving, rect it in a constructive fashion,

1992; Pohl, 1978). Principles for and trial and error foster collabo- thus preventing escalation of the

adult learning stress readiness, ration, and strengthen the bond anxiety that blocks learning,

repetition and reinforcement, between the nurse and patient acceptance, and growth (Peterson

and guide the nurse in determin- (Peterson & Bredow, 2004; Pohl, & Bredow, 2004).

ing the amount, level, and fre- 1978). Validation and acceptance In the orientation phase the

quency of teaching that can be of the fear, tension, and anxiety nurse and the patient discuss

UROLOGIC NURSING / October 2006 / Volume 26 Number 5 365

UNJ Oct 2006-366.ps 9/29/06 3:45 PM Page 366

C their expectations and goals for the beginning of accepting indwelling catheters will be

O initial and future meetings. responsibility for self-care. removed. At this point, the

Mutually agreed upon goals A postoperative goal would patient must learn a new set of

N guide the nurse in developing an be to understand and undertake self-care techniques. The patient

T outline of the treatment protocols the activities that may prevent must be taught to urinate using

I for the urinary diversion with pneumonia and emboli, includ- Valsalva maneuvers and pelvic

which the patient must become ing early vigorous ambulation floor muscle relaxation. Tech-

N familiar. Verbal and written and frequent use of incentive niques for intermittent catheteri-

U descriptions are used to explain spirometer. A second postopera- zation, timed voiding, bladder

I important information. Visual tive goal would be to learn self- diaries, and use of incontinence

teaching aides are also useful care about the tubes draining the products present a new array of

N supplements that greatly en- CUR, the incision care, and the tasks.

G hance the instructional sessions equipment care. Often at dis- Resolution. The final phase,

at this stage and could include charge, 7 to 10 days after surgery, resolution, may begin months

hands-on exposure to an ostomy the patient relies on family mem- after discharge. The patient expe-

E appliance, an anatomical model, bers to assist with care. However, riences a sense of security because

D or pictures. Also included in the early independence helps to fos- his/her needs have been met.

U teaching are the preparations for ter self-esteem and a return to Immediate self-care has been

C surgery such as donation of positive body image. learned and self-reliance is

autologous blood, bowel prepara- A discharge planning goal is increasing. Independence and

A tion, changes in medication, and for the patient to identify an separation from the urology nurse

T a generalized pathway for hospi- emergent situation and outline occurs. The focus switches to

I talized care. the procedures for managing the quality of life issues and long-term

Identification. The identifi- situation. This could include acceptance of the health status.

O cation phase begins when the knowing the signs and symptoms Incontinence, sexual intima-

N patient has a limited understand- of wound infections or urinary cy, and acceptance of body image

ing of the disease (bladder can- tract infections. Other critical sit- changes may require longer

cer), treatment choices, and uations could be nonfunctioning nurse-patient relations (Gray &

potential self-care issues. Based urinary drainage tubes, fevers, Beitz, 2005). Long-term involve-

on prior relationships and previ- and sudden onset of gross hema- ment in a support group provides

ous medical interventions, the turia or abdominal pain. an important and necessary link

patient may identify the need for The patient who is able to to others in their community

help (Peterson & Bredow, 2004). recognize the need for new who are dealing with the same

This phase may involve indepen- skills/knowledge to achieve the concerns and issues (Kane,

dence, over dependence, or com- goals established has effectively 2000b). A sense of security and

plete isolation/rejection of the moved through the identification confidence is derived from the

nurse. The ultimate goal of this phase of the nurse-patient rela- ability to reach out to others

phase is to provide opportunities tionship. Accomplishment of (Forchuk, 1991).

for the patient to attain a level of these goals facilitates movement

readiness to assume responsibili- into the exploitation phase of the Applying Peplaus Theory

ty for his/her care (Peplau, 1997). relationship. The nurse-patient relation-

Goals for this phase could be Exploitation. In the exploita- ship is a key concept in Peplaus

divided into pre-operative, im- tion phase the patient demon- theory. If switching from a theo-

mediate postoperative and dis- strates the ability for self-care retical to practical application is

charge planning. A pre-operative and independence (Peplau, to be effective, the clinician must

goal would be for the patient to 1997). The comfort and trust establish outcome measures that

understand and comply with the level of the nurse-patient rela- incorporate the unique needs of

bowel preparation program. A tionship has been established. the patient (Peplau, 1992; Peterson

second pre-operative goal would Initial goals have been met, & Bredlow, 2004). Outcome mea-

be for the patient to review the allowing an opportunity for fur- sures guide the practitioner in the

written material about the diver- ther growth. Therefore, new assessment of the patients indi-

sion on the eve of the surgery. A goals are identified that prompt a vidual needs, and outline the

review of this material helps temporary return to the identifi- care required. They also provide

him/her to foster independence cation phase. An example: After a means for evaluating the

and maintain a sense of control 2 to 3 weeks post-surgery the progress of the instruction and

during the pre-operative period. bladder incisions have healed related interventions. Peplau

Compliance of these goals indi- and the x-rays indicate no stresses that successful interven-

cates the willingness to learn and extravasations of the dye; the tions only occur if the patient is

366 UROLOGIC NURSING / October 2006 / Volume 26 Number 5

UNJ Oct 2006-367.ps 9/29/06 3:45 PM Page 367

valued and accepted by the nurse. discussed options for continent what he understood about the C

Acceptance is attained by seek- diversion, and explained that his proposed surgery. He was asked O

ing active patient participation in chances for long-term, disease- if he read the material given to

the development of the goals for free recovery were excellent. He him at the last teaching session. N

the interventions. was referred to the urologic nurse He was given the opportunity to T

Suggested outcome measures for additional teaching ask questions, which were then I

for patients undergoing a urinary In the first meeting with the used to direct the teaching ses-

diversion might include: urologic nurse, the patient was sion. Body language, eye contact, N

The patient participates in a very agitated and anxious, and focused attention span all U

bladder cancer/urinary diver- announcing he did not have time indicated the patient was express- I

sion support group pre-opera- for this teaching session and ing his willingness to learn. Based

tively and postoperatively. could not plan any surgery at this upon the patients description of N

The patient is able to engage time due to the constraints of his the surgery, information about G

in self-care activities to sup- business. His immediate con- anatomical changes, pre and post-

port maintenance of the uri- cerns centered on his ability to operative care, and expected

nary diversion. pay his bills, support his family, recovery time were discussed.

E

The patient collaborates with and maintain his business. Visual aids used to enhance the D

the nurse to identify resources Compounding these concerns teaching session included an U

to help him/her cope with were fear, anxiety, grief, and anatomical model of the bladder, C

post-surgical consequences of knowledge deficit regarding the prostate, and seminal vesicles. A

urinary diversion (urinary cancer diagnosis and the need to pictorial drawing of the bowel A

incontinence, sexual dysfunc- undergo surgery to remove his and remodeled bladder helped T

tion, etc.). bladder. His wife was present, the patient to understand the I

and equally anxious and tearful. construction of the new bladder.

Case Study Once the patients concerns The final visual aid was a repre- O

A 60-year-old male is diag- were validated and discussed, sentative picture of his body with N

nosed with muscle-invasive potential community resources the incision marked and the sites

bladder cancer. He was seen by to help them through this diffi- of the various drainage tubes.

his local urologist after two cult time were identified. These The written material given to

episodes of hematuria. Patient included hiring associates who him was a review of the verbal

denied dysuria, urgency, or fre- could work as subcontractors, discussion regarding the pre and

quency. He had no recent weight identifying his wife as temporary postoperative care. Adequate

loss, shortness of breath, or bookkeeper, and involving the time was allowed for the patient

symptoms of bone pain. He social worker to mobilize the and his wife to ask questions. As

underwent a cystoscopy and other available community re- the session concluded, the uro-

bladder biopsy that revealed sources. The initial teaching ses- logic nurse provided the patient

muscle-invasive bladder cancer. sion was concluded with mini- with information about the

He was referred to the academic mal information being given to upcoming monthly support

medical center for further evalua- the patient about the surgery, but group meeting. The patient was

tion and treatment. the steps taken to help him plan encouraged to attend these meet-

Past history included tobac- for his surgery contributed to a ings prior to his surgery. These

co use of three packs/day for 45 significant change in his behav- meetings offer an opportunity for

years; however, the patient ior and willingness to consider patients to share their experi-

stopped smoking 1 year ago after future options. Flexibility in ences, and to support and

a severe upper respiratory infec- addressing the patients primary encourage others beginning this

tion. He works full time as an concerns rather than implement- journey. According to Peplau,

independent painting contractor. ing the planned teaching session developing a new sense of com-

No other health problems were fostered the therapeutic nurse- munity and comfort in a chang-

reported. He is married and has patient relationship. An evening ing environment, such as partici-

two adult sons; the sons are not appointment was made for the pating in support groups, is criti-

employed in his business. The next teaching session, so as to not cal to maintain a positive self-

complete blood count and com- interfere with his painting busi- image and a return to optimal

plete metabolic count, especially ness. He was given written mate- health (Peplau, 1992).

the BUN and creatinine, were rial to review at home prior to the The patient selected the

within normal limits for age. The next session. orthotopic neobladder diversion.

chest x-ray and CT scans of the At the second session, readi- This surgery involves removing

abdomen and pelvis were also ness to learn was assessed. First, the bladder, prostate, seminal

normal. The consulting urologist the patient was asked to explain vesicles, appendix, some of the

UROLOGIC NURSING / October 2006 / Volume 26 Number 5 367

UNJ Oct 2006-368.ps 9/29/06 3:45 PM Page 368

C regional nodes, and subsequent presentation of new information. The physician provided the

O creation of a new bladder which The patient and his wife were patient with the final pathology

is then connected to the urethra. taught to irrigate the neobladder, report that staged the bladder

N This option was chosen because using 0.9 NS in 30 cc increments tumor as T1, N0, M0, indicating

T it provided the most normal to remove mucus and blood that the cancer had not penetrat-

I approach to voiding. The patient clots. They were taught how to ed through the bladder wall and

felt that although the risk of noc- clean the irrigation equipment did not involve any nodes or

N turnal incontinence was approxi- and where to purchase additional spread to any distant sites (see

U mately 10%, the benefits of a supplies as necessary. Teaching Figure 1). As part of the dis-

I less-altered body image out- strategies stressed the impor- charge teaching session, the uro-

weighed the risks. He felt that tance of maintaining the patency logic nurse provided an opportu-

N routine clean intermittent cathe- of the drainage tubes and the nity for the patient to ask ques-

G terization through the stoma consequences of a blocked tions about the pathology report

would impede his ability to con- drainage tube. These lessons and verified his understanding of

tinue his painting business and involved verbal, written, and the results. The return clinic visit

E make it difficult for him to main- hands-on demonstration and and followup x-rays were sched-

D tain his privacy about his return demonstration. Final uled for 2 weeks later.

U surgery. He expressed concerns teaching sessions discussed the At the clinic visit, the x-rays

C about not getting painting con- most common reasons for emer- documented that the neobladder

tracts if customers knew about gency room visits and how to incisions had healed, allowing

A his health condition. He under- prevent the need for these visits. for the urinary drainage tubes to

T stood the risk of erectile dysfunc- A final question and answer peri- be removed. The patient was

I tion was similar for all of the sur- od was arranged prior to dis- instructed on daily self-catheteri-

gical options presented to him. charge. The patient was also zation, voiding techniques,

O Two units of autologous blood given access numbers for the timed voiding, and use of the

N were donated in the weeks prior nurse and the physicians. diary. He was also instructed that

to the surgery. He stopped all Short-term goals included the bladder would continue to

aspirin and aspirin-containing maintenance of the integrity of expand in size over the next year.

medications as well as all over- the urinary diversion, return to Early incontinence was expected

the-counter medications 1 week normal activity, improved nutri- and would improve as bladder

prior to surgery. Bowel-cleansing tional status, and perhaps most capacity increased and pelvic

procedures began on the day importantly a focus on the psy- floor muscles strengthened over

before surgery and included oral chosocial aspects of recovery. the next few months.

intake of 3 ounces of Fleet phos- Anxiety, fear, anger, and depres- Porter, Wei, and Penson

phosoda at 10 a.m., followed by sion can impede the learning (2005) identify three common

clear liquids only and antibiotics process. Utilization of clergy, quality-of-life issues that these

(1 gram of neomycin and ery- social service, or psychologists patients experience: decreased

thromycin, at 1 p.m., 2 p.m., and may be beneficial and should be sexual functioning, inconti-

10 p.m.). He was instructed to considered. nence, and altered body image.

not eat or drink after midnight. The patient was discharged Long-range goals for the first

The patient was admitted to on postoperative day 8. He postoperative year were devel-

the hospital 2 hours before the demonstrated care of the urinary oped focusing on these issues.

surgery and taken to the pre- drainage tubes and incision. He Sexual function changes could

admission area. In the pre-admis- was given supplies for home use. include an inability to obtain or

sion area he was again seen by He verbalized the importance of maintain an erection, an inability

the urology nurse who reviewed adequate protein in his diet and to have an ejaculation, dimin-

the education material and re- the need for six small meals ished orgasms, and/or decreased

affirmed his choice of surgical daily. He also was to start taking libido. Incontinence issues are

intervention. Opportunity to ask a multivitamin daily. Protein bars present because of the anatomi-

questions was given. The patient and shakes had been purchased cal changes during the diversion

was then marked for an optimal by his wife for home use. The surgery but usually improve

stoma site in the event the patient stated that drinking two within a year. Body image

neobladder was unable to be per- quarts of fluid a day seemed dif- changes are related to an alter-

formed. ficult but he understood that it ation in elimination patterns, a

While hospitalized, daily was necessary. Family members change in sexual functioning,

teaching sessions were planned, were recruited to assist him in and the impact of the cancer

consisting of a review of the pre- his daily walks, and provided diagnosis (Jenks, Morin, &

vious days lessons as well as needed social contacts. Tomaselli, 1997). These changes

368 UROLOGIC NURSING / October 2006 / Volume 26 Number 5

UNJ Oct 2006-369.ps 9/29/06 3:45 PM Page 369

Figure 1. He attained daytime continence C

Comparison of AJCC and Jewett-Strong-Marshall within 4 months of the surgery. O

Staging Systems The body image changes that

these patients experience are sig- N

TNM Jewett-Strong nificant but can resolve as self- T

Definition

Classification Marshall confidence and independence I

Tis 0 Limited to mucosa, flat insitu increase. The process of adapting

to these changes or the re-imag- N

Ta 0 Limited to mucosa, papillary ing of ones self is aided by a suc- U

T1 A Lamina propria invaded cessful nurse-patient relation- I

ship and a patient-community

T2a B1 < halfway through muscularis

relationship. Monthly attendance N

T2b B2 > halfway through muscularis at a support group helped the G

T3 C Perivesical fat patient develop a strong sense of

community. Individual problems

T4a C Prostate, uterus or vagina

and concerns were discussed

E

T4b C Pelvic wall or abdominal wall freely resulting in shared knowl- D

N1-N3 D1 Pelvic lymph node(s) involved edge by all members of the group. U

The urologic nurse facilitated C

M1 D2 Distant metastases these meetings and invited guest

speakers to present topics rele- A

vant to their post-diversion care. T

In time, the patient became a I

resource for new patients under-

going urinary diversion. An O

interesting outcome of these N

meetings was the interaction

between fellow members as they

helped each other establish new

goals such as traveling, managing

unsanitary bathroom conditions,

and packing equipment for over-

seas trips. The patient also con-

tributed to efforts to develop tips

for traveling booklets, guidelines

Source: SEER Training Web Site (2005).

for emergency room visits, and

even suggestions on airport facil-

ity use.

may result in loss of self-esteem, jections with papaverine, pro- Quality-of-life issues im-

depression, and sense of isola- staglandin, and phentolamine proved for the patient over the

tion, anger, or fear (Jenks et al., were initially successful, but course of 5 years. He returned to

1997). decreased in efficacy over the work full time, money issues

This patient noted an inabili- subsequent 5 years. resolved, and many of the life

ty to obtain an erection, decreased Although nocturnal enuresis changes were accepted. Concerns

libido, and had no orgasms or is a common complication of regarding return of the cancer,

ejaculations. Despite penile reha- orthotopic neobladder diversion, diminished sexual functioning,

bilitation, the early onset of treat- the incidences of nighttime and altered body image remain

ment for erectile problems, the incontinent episodes 6 months and may persist throughout his

sexual dysfunction continued. post-surgery were rare and ade- lifetime. The patient expressed

Oral agents for erectile dysfunc- quately managed by placing a gratitude for the nurse(s) whose

tion were started at 2 months and minipad in his underwear. teaching and support aided him

used periodically during the first Nocturnal continence was at- in his return to optimal health

year post-surgery with minimal tained, in part, by teaching the status.

response. Although the vacuum patient to perform Kegel exercis-

device and the penile prosthesis es on a regular basis, empty the Summary

implant are viable treatments, the bladder before bedtime, and In conclusion, a highly

patient did not wish to consider adhere to a diet and fluid regi- skilled urologic nurse with good

these options. Intracorporal in- men to prevent constipation. observation and communication

UROLOGIC NURSING / October 2006 / Volume 26 Number 5 369

UNJ Oct 2006-370.ps 9/29/06 3:45 PM Page 370

skills plays a critical role in pro- September 17, 2006, from http:// Perimenis, P., & Koliopanou, E. (2004).

C moting the health of patients www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/CA Postoperative management and reha-

O FF2006PWSecured.pdf bilitation of patients receiving an ileal

undergoing urinary diversion. Fleischer, I., & Bryant, D. (2005). orthotopic bladder substitution.

N The scope of patients needs Prescription for excellence: An ostomy Urologic Nursing, 24(5), 383-386.

T require a nurse competent to clinic. Ostomy Wound Management, Peterson, S.J., & Bredow, T.S. (2004).

assume the changing roles in the 51(9), 32-38. Middle range theories: Application to

I four phases of the interpersonal Forchuk, C. (1991). Peplaus theory: nursing research. Philadelphia:

Concepts and their relations. Nursing Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins.

N process described by Peplau Science Quarterly, 4(2), 54-60. Pohl, M.L. (1978). The teaching function of

U (1992; 1997). Peplaus theory Gray, M., & Beitz, J.M. (2005). Counseling the nursing practitioner (3rd ed.).

emphasizes that effective com- patients undergoing urinary diver- Dubuque, IA: Brown Company

I munication is integral to the sion. Journal of Wound, Ostomy, and Publishers.

Continence Nursing, 32(1), 7-15. Porter, M.P., Wei, J.T., Penson, D.F. (2005).

N nurse-patient relationship and Jenks, J., Morin, K., & Tomaselli, N. (1997). Quality of life issues in bladder can-

G necessary for educational efforts The influence of ostomy surgery on cer patients following cystectomy and

to be successful. To that end, it is body image in patients with cancer. urinary diversions. Urologic Clinics of

important to involve the patient Applied Nursing Research, 10(4), North America, 32, 207-216.

E 174-180. SEER Training Web Site. (2005). Bladder

in establishing the teaching Kane, A.M. (2000a). Nursing management cancer staging. U.S. National

D goals, conduct frequent review of of neobladder surgery. Urologic Cancer Institutes Surveillance,

these goals, and evaluate the effi- Nursing, 20(3), 189-197. Epidemiology and End Results

U cacy of teaching methods used. Kane, A.M. (2000b). Criteria for successful (SEER) Program. Retrieved July 10,

C Applying this theory to practice neobladder surgery: Patient selection 2006, from http://training.seer.can-

and surgical construction. Urologic cer.gov/ss_module05_bladder/unit03

A helps the urologic nurse evaluate Nursing, 20(3), 182-188. _sec04_staging.html

T and develop skills and teaching Peplau, H.E. (1992). Interpersonal relations:

methods to meet the needs of A theoretical framework for applica- Additional Reading

I each patient. tion in nursing practice. Nursing National Cancer Institute. (2005). A snap-

Science Quarterly, 5(1), 13-18. shot of bladder cancer statistics.

O Peplau, H.E. (1997). Peplaus theory of Retrieved July 10, 2006 from

References

N American Cancer Society. (2006). Cancer

interpersonal relations. Nursing http://planning.cancer.gov/disease/Bl

Science Quarterly, 10(4), 162-167. adder-Snapshot.pdf

facts and figures 2006. Retrieved

Adult-Learning Processes

continued from page 352

Jezierski, J. (2003). Discussion and

demonstration in series of orienta-

tion sessions. Presented at St.

Certification Board for Urologic Nurses Elizabeth Hospital Medical Center,

and Associates Lafayette, IN.

Knowles, M.S. (1970). The modern prac-

tice of adult education: Androgogy

ATTENTION ADVANCED versus pedagogy. New York: New

York Association Press.

PRACTICE NURSES Lieb, S. (1991) Adult learning principles.

Retrieved April 28, 2005, from

The Certification Board for Urologic Nurses http://honolulu.hawaii.edu/intranet

and Associates has an announcement that /committees/FacDevCom/guidebk/t

eachtip/adults-2.htm.

may affect you. Beginning January 1, 2006 OBrien, G. (2004). Principles of adult

and ending December 31, 2008, Advanced learning. Melbourne, Australia:

Southern Health Organization.

Practice Nurses who are NOT Masters pre- Retrieved December 2, 2005, from

pared but LICENSED by their state as http://www.southernhealth.org.au/c

pme/articles/adult_learning.htm

advanced practice nurses will be given an Richardson, V. (2005). The diverse learn-

opportunity to sit for the Advanced Practice ing needs of students. In D.M.

Certification Exam. Billings & J.A. Halstead (Eds.),

Teaching in nursing (2nd ed.). St.

This window of opportunity is limited to the Louis, MO: Elsevier.

above dates and will not be offered again. Rogers, C.R. (1969). Freedom to learn.

Columbus, OH: Merrill.

To download an application, go to Zemke, R., & Zemke, S. (1995, June). Adult

www.suna.org, then click the Certification learning What do we know for sure?

Training. Retrieved July 11, 2006, from

tab, or call C-Net at 1-800-463-0786. http://www.msstate.edu/dept/ais/852

3/Zemke1995.pdf

370 UROLOGIC NURSING / October 2006 / Volume 26 Number 5

You might also like

- AbstractDocument9 pagesAbstractardiansyahNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 11Document8 pagesJurnal 11basok buhariNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 11 InternasionalDocument8 pagesJurnal 11 Internasionalbasok buhariNo ratings yet

- Deming PDFDocument4 pagesDeming PDFPayal SaxenaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 11 InternasionalDocument8 pagesJurnal 11 Internasionalbasok buhariNo ratings yet

- Juranl 7Document3 pagesJuranl 7basok buhariNo ratings yet

- International Comparison of Nine Accreditation Programmes For Ambulatory Care FacilitiesDocument9 pagesInternational Comparison of Nine Accreditation Programmes For Ambulatory Care Facilitiesbasok buhariNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 1Document7 pagesJurnal 1basok buhariNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Nurse Behavior and Competence in Patient SafetyDocument8 pagesRelationship Between Nurse Behavior and Competence in Patient Safetybasok buhari100% (1)

- Jurnal MHCLN PeplauDocument10 pagesJurnal MHCLN Peplaubasok buhariNo ratings yet

- International Comparison of Nine Accreditation Programmes For Ambulatory Care FacilitiesDocument9 pagesInternational Comparison of Nine Accreditation Programmes For Ambulatory Care Facilitiesbasok buhariNo ratings yet

- Acmhn Documenting Clinical SupervisionDocument14 pagesAcmhn Documenting Clinical Supervisionbasok buhariNo ratings yet

- Clinical Supervision Policy V3Document29 pagesClinical Supervision Policy V3basok buhariNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Rekapitulasi Laporan Psikotropika Bandung BaratDocument8 pagesRekapitulasi Laporan Psikotropika Bandung BaratFajarRachmadiNo ratings yet

- Correlation of Sound and Colour - Paul Foster CaseDocument30 pagesCorrelation of Sound and Colour - Paul Foster Casesrk777100% (7)

- IMCI Chart BookletDocument66 pagesIMCI Chart Bookletnorwin_033875No ratings yet

- Medical services tariffs starting 2016 and on-request servicesDocument16 pagesMedical services tariffs starting 2016 and on-request servicesIonutNo ratings yet

- 9700 w14 QP 23Document16 pages9700 w14 QP 23rashmi_harryNo ratings yet

- Medical ReceptionistDocument4 pagesMedical ReceptionistM LubisNo ratings yet

- Tfios Mediastudyguide v4Document7 pagesTfios Mediastudyguide v4api-308995770No ratings yet

- Golden NumbersDocument89 pagesGolden NumbersjoobazhieNo ratings yet

- Introduction To QBD FixDocument25 pagesIntroduction To QBD FixAdel ZilviaNo ratings yet

- Medicine, Coptic.: Chronological Table of Ostraca and Papyri Dealing With MedicineDocument7 pagesMedicine, Coptic.: Chronological Table of Ostraca and Papyri Dealing With MedicinePaula VeigaNo ratings yet

- Antibacterial and Antifungal Activities ofDocument6 pagesAntibacterial and Antifungal Activities ofSamiantara DotsNo ratings yet

- Patient Safety and TechnologyDocument5 pagesPatient Safety and TechnologyAditya Toga100% (1)

- 2 Months To LiveDocument26 pages2 Months To LivedtsimonaNo ratings yet

- HCQ in COVIDDocument28 pagesHCQ in COVIDAppu EliasNo ratings yet

- CPHQ Review Course Nov 28-29 2012Document195 pagesCPHQ Review Course Nov 28-29 2012Khaskheli Nusrat100% (2)

- PhysioEx Exercise 5 Activity 5Document3 pagesPhysioEx Exercise 5 Activity 5Gato100% (1)

- Cold TherapyDocument27 pagesCold Therapybpt2100% (1)

- Fluconazole Final Dossier - Enrollemt Number 2Document139 pagesFluconazole Final Dossier - Enrollemt Number 2lathasunil1976No ratings yet

- Levorphanol - The Forgotten Opioid PDFDocument6 pagesLevorphanol - The Forgotten Opioid PDFfchem11No ratings yet

- Plasmid-Mediated Resistance - WikipediaDocument16 pagesPlasmid-Mediated Resistance - WikipediaUbaid AliNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Surgical Handbook PDFDocument139 pagesPediatric Surgical Handbook PDFNia LahidaNo ratings yet

- Acute Lymphoblastic LeukaemiaDocument3 pagesAcute Lymphoblastic LeukaemiamelpaniNo ratings yet

- What Is Stress PDFDocument4 pagesWhat Is Stress PDFmps itNo ratings yet

- PharmacologyDocument9 pagesPharmacologyAishwarya MenonNo ratings yet

- Journal ReadingDocument14 pagesJournal ReadingDesrainy InhardiniNo ratings yet

- CPG 2013 - Prevention and Treatment of Venous ThromboembolismDocument170 pagesCPG 2013 - Prevention and Treatment of Venous ThromboembolismMia Mus100% (1)

- Comparison of Roth Appliance and Standard Edgewise Appliance Treatment ResultsDocument9 pagesComparison of Roth Appliance and Standard Edgewise Appliance Treatment ResultsseboistttNo ratings yet

- 1 Gram Positive Bacterial InfectionDocument87 pages1 Gram Positive Bacterial InfectionCoy NuñezNo ratings yet

- Pes WesDocument12 pagesPes WesjotapintorNo ratings yet

- Netter 39 S Internal Medicine 2nd Edition Pages 65, 68Document2 pagesNetter 39 S Internal Medicine 2nd Edition Pages 65, 68Burca EduardNo ratings yet