Professional Documents

Culture Documents

NOMIC Através Do Jornalismo (2003)

Uploaded by

Pedro AguiarOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

NOMIC Através Do Jornalismo (2003)

Uploaded by

Pedro AguiarCopyright:

Available Formats

Journalism

http://jou.sagepub.com

Envisioning a New World Order Through Journalism: Lessons from

Recent History

Sujatha Sosale

Journalism 2003; 4; 377

DOI: 10.1177/14648849030043007

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://jou.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/4/3/377

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Journalism can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://jou.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://jou.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations http://jou.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/4/3/377

Downloaded from http://jou.sagepub.com by Pedro Aguiar on November 11, 2008

Journalism

Copyright 2003 SAGE Publications

(London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi)

Vol. 4(3): 377392 [1464-8849(200308)4:3;377392;034042]

ARTICLE

Envisioning a new world order

through journalism

Lessons from recent history

j Sujatha Sosale

Georgia State University

ABSTRACT

Journalism and communicative democracy in general were debated intensely on a

world scale a quarter of a century ago, during the debates over a New World

Information and Communication Order. In this article, I demonstrate that during this

period, theory and reflexive practice in journalism were envisioned through radical ideas

freely deliberated in intergovernmental, professional and scholarly spaces. I analyze

related themes that appeared in statements issued by Third World journalists, and in

selected scholarly articles published at that time. Analysis reveals that these themes

articulated an alternate, more democratic world order. I conclude by discussing the

relevance and importance of these ideas and themes to the present global era.

KEY WORDS j alternate world order j global democracy j globalization

j journalistic practice j social theory

The state of journalism and its role in engendering global democracy were

debated on a world scale intensely a quarter of a century ago. They constituted

the core of the efforts to formulate a policy towards a New World Information

and Communication Order (NWICO). Tied as the debates were to UNESCO

action and superpowers membership in this organization, after the with-

drawal of the US and Britain from the organization in 1984 and 1985

respectively, the debate lost the momentum that it had achieved in the decade

of 197685. However, it would be incorrect to dismiss the debates as a failure.

Nor can we claim that a discursive closure has ended the reality of the need to

achieve global communicative democracy today. Some of the recommenda-

tions that emerged from the NWICO debate have been put into practice, such

as the creation of regional news agencies intended to ensure greater parity in

news flows and fair media representations, even if they struggle to survive

because of the lack of sufficient funds (Boyd-Barrett and Thussu, 1993).

Downloaded from http://jou.sagepub.com by Pedro Aguiar on November 11, 2008

378 Journalism 4(3)

Another serious effort at resisting discursive closure of the NWICO idea is

apparent in the MacBride Round Tables held annually for the past decade or so

(198998). The MacBride Round Tables continue to keep the NWICO argu-

ments and ideas on the research, practice and policy agenda and also recom-

mend action for adapting to changing media and social conditions and

contexts (Vincent and Traber, 1999). What is worth examining, and relevant

and important now, are some of the radical suggestions that emerged in the

NWICO context that can serve to redefine an alternate world order today,

especially from the standpoint of a practice that continues to create, control

and reproduce a public symbolic domain in the global era journalism.

The analysis that follows takes contestations of the dominant professional

ideology and its structuring of the world order as its point of departure. In a

now classic essay, Golding (1977) has attributed the origins of this ideology to

western journalistic practices. Western journalists and their supporters op-

posed the NWICO ideas on some critical grounds. As journalist Righter (1978)

interpreted it, NWICO ideas and strategies were a rejection of the ideals of

individual opportunity and freedom of choice, coming mainly from author-

itarian governments. Remedies proposed to change the existing world order

were remedies of authoritarianism (Righter, 1978: 14). Journalistic circles in

the First World rejected many NWICO solutions on grounds that they would

violate the publics right to be informed because of state control of commu-

nication. NWICO remedies for an imbalanced world communication order

were seen as a radical alternative creating a reverse apartheid (Righter,

1978: 100). However, NWICO proponents held that the existing system had

caused the apartheid in global communication due to historical developments

and that corrections to the world order required redefinitions of professional

practices and ethical parameters.

Redefinitions often involve challenging enduring significations of terms

from alternate perspectives. In the context of this study, they are symbolic of

the aspirations of developing nations for certain material and social conditions

in their everyday realities. The communication context and social conditions

have changed with the advent of the post-industrial, information society.

Advocates of the information society view new information and communica-

tion technologies (ICTs) as a strong facilitator of democracy. A popular argu-

ment is that globalization, through ICTs, offers a completely new array of

commercial and cultural advantages to all, worldwide. This enthusiasm seems

to be directed more towards the potential contained in ICTs than their actual

material distribution in the current world order, which suggests a different

picture (the global digital divide). Some social theorists caution us against such

optimism. For example, Webster (1995) sees an exacerbation in the adverse

conditions of global capitalism (his dystopian view) with the advent of ICTs.

Downloaded from http://jou.sagepub.com by Pedro Aguiar on November 11, 2008

Sosale Envisioning a new world order through journalism 379

May (2002) argues that when stripped, the changes accompanying the

transformation into the global information society are superficial, and that the

underlying substance (capitalism) remains the same. Even allowing for the sea

changes wrought by globalization, in some fundamental ways, the context

within which the NWICO debates occurred has not changed radically. If

anything, the desire to improve material conditions and life opportunities has

intensified. As it has also been pointed out, global media power continues to

hold sway and journalism continues to engage with and be implicated in

media power. Thus the way in which a new world order was imagined 25 years

ago and the need for re-imagining one now become a critical area of inquiry in

the current conditions.

I approach this problematic on a conceptual level by using a combination

of the Wallersteinian world system and Giddens structuration theories as a

basis for demonstrating how journalism can re-orient images and perceptions

of world order through changes in journalistic approach and practice.1 These

changes suggest the potential to dissolve the hierarchy apparent in the centre

periphery arrangement (and its current variants in the era of globalization)

and, in a sense, return sociality (Appadurai, 1990) to the journalistic form of

communication. An alternate world order, imagined in the 1970s from a

journalistic standpoint, can be evoked in the present context. While the term

alternate is often used in relation to specific media, media forms and media

communities, the term applies to this project a little differently. Here, I apply

the term to a macro-social perspective and present an outline of mechanisms

articulated by journalists and professionals involved in the NWICO debates for

helping re-imagine an alternate (world) society. Thus, an alternate society

could be conceptualized in the public imaginary through changes in journal-

istic practices and related concepts (such as the notion of audience).

Working with an interpretive thematic analysis of a selection of seminar

and conference reports and journal articles generated between 197685, when

debates about distributive justice in world communications were at their

height during the NWICO debates, I demonstrate how theory and practice in

journalism were envisioned during an unusual period when radical ideas were

freely voiced in deliberations in intergovernmental, professional and scholarly

spaces. NWICO debates ended in an impasse of sorts between rejection of

government-intervention measures on the one side and opposition to oligopo-

listic control of world media communications on the other. While many

opponents to the new policy frequently let their opposition to the role of the

state overshadow the variety of suggestions offered by proponents of the

NWICO, the latter did not adequately account for the full implications of state

intervention in citizens right to be informed. However, arguments for

alternative journalisms that contained the potential to define a new global

Downloaded from http://jou.sagepub.com by Pedro Aguiar on November 11, 2008

380 Journalism 4(3)

communication order detailed a far more nuanced, textured and negotiated

approach to changes than the impasse would suggest. This study attempts to

present some of the concrete suggestions that articulated the nuances and

negotiations in the course of the NWICO debate. Specific themes that emerged

during the debates included diffusing journalistic power from the centre,

power balances in gate-keeping practices and a redefinition of public opinion

in relation to the notion of civil society.

A theoretical discussion of the concept of world system and structuration

theories is provided by way of an introduction, followed by a note on the

method and mode of analysis. I then present the major themes that emerged

from the analysis diffusing the centre, changes in gate-keeping and the

achievement of attendant balances of power and the concept of public

opinion in relation to the notion of a civil society. I conclude with the

relevance and implications of this analysis for the 21st century.

A note on the vocabulary terms such as the Third World, the North and

the South will appear frequently in the analysis. This is partly because of their

usage in the period central to this study. It is also because these terms continue

to signify the global order today (excellent discussions on the historical origins

of these terms and their albeit uncomfortable currency are available in Escobar

[1995] and Melkote and Steeves [2001]).

The hermeneutic of the world order and its implications for

journalism

Over time, our perceptions of our larger social environments have been shaped

to register the world as a single world system. Robertson uses the term central

hermeneutic to articulate our mode of making sense of the world as a singular

construct (Robertson, 1990: 20). Originally a theory proposed by historian

Immanuel Wallerstein (1974), the idea of a world system is now a standard

descriptor of the international/global space. Two critical components contrib-

ute to the construction of this meaning. First, the world (geopolitical space)

converged into a single order as a consequence of a long history (the longue

duree). Second, the hierarchical nature of this arrangement is based on the

relative economic strengths of the member nations, moving radially from the

powerful core or the centre to the semi-peripheral nations (the Second World)

and finally the peripheral nations (the Third World) at the margins. Achieving

global communicative democracy in such an arena would entail changing this

hierarchical structure into a more horizontal one.

The theory of structuration, proposed and developed by sociologist An-

thony Giddens, also provides the foundations for understanding the world as

Downloaded from http://jou.sagepub.com by Pedro Aguiar on November 11, 2008

Sosale Envisioning a new world order through journalism 381

a whole. Structuration involves the interplay of both structure (the social

system and institutions) and agency (the individual, the subject) as simultane-

ously deriving from and constituting society. Political sense can be made of

structuration because

processes of structuration involve an interplay of meanings, norms and power.

These three concepts . . . are logically implicated in both the notion of inten-

tional action and that of structure. Every cognitive and moral order is at the same

time a system of power. (Giddens, 1993: 169)

Robertson offers an interpretive bridge between structuration and the idea of a

world order in his adaptation of the theory to help formulate a theory of

globalization. To make the concept of structuration directly relevant to the

world in which we live (Robertson, 1990: 20), he asserts that the current

globalizing world is structuration in action. The world as a singular space

fundamentally informed the idea of communicative democracy. Importantly,

this singular space is constantly under construction. Perceiving the world

system as a hierarchy politicizes the global society. The concept of the duality

of structure (Giddens, 1986), that is the dynamic relationship between struc-

ture and agency, speaks to the possibility for changing the world order. The

NWICO debates have to be located in this perception of the world order as

dynamic, constantly under construction. The duality of structure is thus

played out in a Cold War environment, where journalism in western demo-

cratic states was perceived to define in good part the global communication

order and, in turn, opponents to the existing world order were perceived to

ally their new policy suggestions with the ideology of state control attributed

to the Soviet Union, which wielded considerable influence over the polity and

policies of many Third World nations. A third set of actors needs to be

considered here NWICO supporters from the non-aligned countries (the NAM

or the Non-aligned Movement, where a large group of countries chose a third

way in their bid to separate themselves from a system defined and divided by

the Cold War) aggressively promoted a NWICO. On the whole, however, while

many NWICO proponents were interpellated by the world system, they, in turn,

attempted to construct new meanings of a world order defined by this system.

By extension, redefinitions occurred in the field of journalism as well. These

new meanings were drawn from the existing vocabulary of democracy in

other words, at this time, both professionals and pundits offered negotiated

readings of communicative democracy. Alternative views on journalism thus

sought to redress an imbalanced world communicative order by redefining

practices such as gate-keeping and creation of an appropriate climate of public

opinion among First World audiences. These concepts were extended to a

more shared and broader set of actions and outcomes than existing practices

that, though embedded in the desirable ideal of democracy, had through

Downloaded from http://jou.sagepub.com by Pedro Aguiar on November 11, 2008

382 Journalism 4(3)

institutionalization and commercialization, corporatized these activities in the

interests of tight deadlines, readership/viewership and the market.

Featherstone has interpreted structuration as a concept where nation-

states are not seen to simply interact but to constitute a world (Featherstone,

1990: 5). Further, render[ing] the world into a singular place through

different historical trajectories (Featherstone, 1990: 6; emphasis added) also

finds a place in envisioning another world order. The existing world order

was a result of the historical experiences of conquest and colonization.

Proponents of a NWICO advocated a change that would emerge from the

collective modern communications experiences of countries with a shared

history of colonial occupation, varied though the trajectories and forms of

colonial occupation and experiences have been.

A demand for a new international economic order intended to change this

hierarchy was made in the early 1970s, followed by a demand for a new

international communication order in the mid-1970s. It was reasoned that a

change in the information and communication order was a co-requisite for

changing the existing world system and it is in this context that the NWICO

debates emerged. The United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural

Organization (UNESCO) constituted the locus of the debates for a NWICO. As

an organization invested with officially recognizing the sovereignty of all

member nations (many of which were newly independent ex-colonies) to

legitimate their independent status in the international arena, UNESCO pro-

vided a forum in which a discourse of democracy and development was

constructed.

Both the critique of the existing world order and a new vision were

predicated upon the hermeneutic of a world order. Journalists suggested

certain professional practices and perspectives that contained the potential to

change images and impressions of the existing world order in the minds of the

public. While these suggestions and positions were not necessarily new in and

of themselves, they emerged in a specific context (the struggle for a new global

democracy) and, in this study, from specific sources such as journalists from

developing regions. Many non-Third World proponents of the NWICO also

contributed to the debates but in keeping with the scope and limits of this

study, I confine myself to articulations of alternate journalism and world order

from journalists of developing regions as a start. There is potential to expand

the study to include all pertinent attempts at restructuration within the

theoretical framework offered here in future work. But importantly, these

suggestions and positions become particularly noteworthy for the present

context where concerns that surfaced in the NWICO decade remain in-

adequately addressed.

Downloaded from http://jou.sagepub.com by Pedro Aguiar on November 11, 2008

Sosale Envisioning a new world order through journalism 383

Method and mode of analysis

This study is historical in nature and is situated in the context of the recent

NWICO debates, which can be mapped roughly between 197685. Texts were

selected from a bibliography of all materials dealing with the NWICO com-

piled by the Dag Hammarskjold Libraries, published in 1983, a year short of

the resignation of the United States from UNESCO. The bibliography contains

materials published approximately around this time period and lists UN as

well as non-UN material (published in scholarly and other forums). The texts

for this analysis were selected for their direct contribution to the topic at hand

journalisms role in defining an alternate (new) world order based on

distributive justice in communicative power. Most of the texts relating to the

NWICO, in general, call for an alternate world order. However, the texts

chosen for this analysis address specifically the ways in which journalism can

work to reconstitute a new world system.

A broad, interpretive analysis of the selected texts has been adopted for

the study. Interpretation is understood as the creative construction of possible

meaning (Thompson, 1990: 22). Though interpretive analysis contains the

potential to yield a variety of meanings (limited, of course, by the cultural

context), it does not preclude sharing the meanings with a community of

concerned scholars, professionals and activists. Moreover, multiple meanings

may point to more options for generating suitable action for social change.

Counter-imaginings of a world order challenged the power of existing

meanings of terms such as gate-keeping, public opinion, community journal-

ism and collective cultures and life worlds. An opening for social change

begins with a change in a social understanding of world order. As Hall

(1985: 36) reminds us:

The signification of events is part of what has to be struggled over, for it is the

means by which collective social understandings are created and thus the

means by which consent for particular outcomes can be effectively mobilized.

We can interpret such collective social understandings to be an articulation of

another world order as a historical possibility.

Three themes emerged from the analysis. Attempts to envision an alter-

nate world communication order that would change the centreperiphery

arrangement are apparent in the first theme. The vision of this new world

order retained the hermeneutic of the world system but diffused the centre by

articulating conceptual and practical avenues for the distribution of power in

the symbolic arena (domain of journalism). A second theme engaged in

changes to gate-keeping practices and their consequences for a new world

order. Emerging from the third theme is a way of conceptualizing audiences

Downloaded from http://jou.sagepub.com by Pedro Aguiar on November 11, 2008

384 Journalism 4(3)

from a civil society perspective, as communities and publics that form civil

society. Such a conceptualization recognizes multiple publics within the

sphere of a media system and differs from the use of the concept of public

opinion for polling practices that gauge the mood of a larger and less defined

notion of the public. Together, these themes suggest a different or alternate

world order that would reflect distributive justice in communicative power.

Diffusing the journalistic centre

A statement issued by the participants of a Third World journalists seminar in

1976, the year when an official call for a NWICO was made in UNESCO,

argued for a reorganization in thinking about a world order. This statement

was reprinted in the journal, Development Dialogue (see Abtroun et al., 1982),

and I refer to this reprint in the analysis that follows. Unlike in other forums

where, typically, official representatives and academics debated the issue, this

seminar was organized for Third World journalists. The statement was issued

by journalists from Algeria, Senegal, Pakistan, Peru, Sri Lanka, India, Ven-

ezuela, Tanzania and one participant representing Chile and Mexico. In this

unusual forum, Third World practitioners voices were heard on journalistic,

historical and developmental issues. The statement called for collective self-

reliance . . . at regional and interregional levels (Development Dialogue, 1981:

116), referring to collectives needed in the non-core areas. They called for an

interlinking of national news agencies in the developing regions either directly

or through various bilateral and multilateral exchanges, some of which were

already in existence. The idea of linking national news agencies would contrib-

ute to the formation of regional journalistic collectives mostly with existing

resources (a few regional news agencies were established a little later, such as

the Non-aligned News Pool (NANAP), DepthNews in-depth reporting devel-

opment, economics and population themes and some others (see Boyd-

Barrett and Thussu [1993] and Savio [1982]). Besides regional cooperation for

content, suggestions were also made to reorganize communication channels

still dependent or which constitute a colonial inheritance and obstruct direct

and rapid communication among non-aligned countries (Abtroun et al.,

1981: 116). Here, the participants emphasized the leading role states were

required to play in this reorganization, a highly sensitive issue between

proponents and opponents of the NWICO.

The seminar participants also suggested specific steps to redirect the flow

of information carrying certain types of content. For example, exchang[ing]

and disseminat[ing] on mutual national achievements in the various news

media among states in the developing regions would ensure news content

Downloaded from http://jou.sagepub.com by Pedro Aguiar on November 11, 2008

Sosale Envisioning a new world order through journalism 385

informative of social conditions relevant to the periphery. Additionally, the

participants called for a Third World Information Centre to address Third

World needs specifically and also, to disseminate information to both in-

dustrialized and other regions. Taken together, disengagement from a colo-

nial communication system, re-orientation of a hitherto almost one-way news

flow among non-aligned and other Third World countries, and a significant

amount of news flow from the periphery to the other tiers of the world system

clearly indicate a re-structuration of the world from a Third World per-

spective.

In a UNESCO-commissioned work on development communication in

India, Verghese (1978) proposed a specialization model that could reorganize

the operation of existing news agencies at two levels is the Indian context.

This analysis pertains to the practice of news distribution. At the national

level, Verghese proposed that the four major national news agencies specialize

on the basis of region and language. They could then cater more adequately to

regional language news and information needs in rural areas, a service that is

critical for the language press in a multilingual country like India. At the

international level, these agencies could pool their operations to offer a

specialization in Asian and Indian Ocean coverage for the international news

community. These measures suggest a more geopolitically intuitive distribu-

tion of news power to peripheral regions that is missing in the new global

order.

Besides regional resource pooling and regional specialization, Savio, a

former Director of the Inter Press Service, conceptualized a world with multi-

ple voices, multiple flows and multiple actors where choices would be avail-

able for linking to various streams of information (Savio, 1982). Multiple flows

of information could become a reality only if third systems of information

were integrated into the world communication order. Third systems would

comprise various social groups which make up the texture of society trade

unions, academic institutions, cooperatives, religious movements and peoples

association, and would produce and disseminate information largely absent

in the mainstream media (Savio, 1982: 756). Far from being alternative,

third systems of media would join the mainstream media and render the latter

as one among multiple voices rather than allow it to be the dominant voice in

the world order. Savios vision pertains to alternate sources of information as

part of the multiple voices in a new world order.

We can conclude from this analysis that both conceptual and pragmatic

solutions were provided during the NWICO debates for diffusing journalistic

power concentrated in the centre of the world system. Establishing new

collectivities and self-reliance in the periphery, re-directing flow, outlining

multi-level models of specialization in news agency operation at the national

Downloaded from http://jou.sagepub.com by Pedro Aguiar on November 11, 2008

386 Journalism 4(3)

and international levels, and adding third systems of information as non-

alternative, independent streams of information that ultimately contribute to

a multiplicity of sources and flows at the international level were some of the

means proposed to re-structurate the world order through the symbolic

domain of journalism among both practitioners and publics.

Gate-keeping and balances in symbolic power

It is conventional wisdom now that one of the loci of power wielding

considerable influence in the symbolic arena is the complex of gate-keeping

practices in media organizations. Gate-keeping controls both the type as well

as volume of social and cultural representations in the domain of what

Thompson (1990) has termed public visibility. It is possible, then, to effect

changes in the perceptions of a world order through the symbolic domain of

the media by modifying gate-keeping practices. For example, Savio (1982)

emphasized the need to educate gatekeepers of the North on the importance of

publicizing information not regularly available in their main national media.

If we carry this idea a little further, we can see that routinely including such

information or routinization of this practice of looking in other places for

news contains the potential to orient media images and public perceptions

towards a new world order. As Giddens (1986: 60) has observed, routinization

. . . is vital to the theory of structuration and, in this instance, can work to

represent a different world order.

In an evaluation of international communication following his case study

on the development of the press in Pakistan, Gauhar (1981) cited the (rare)

example of one of Britains leading newspapers, The Guardian, which began a

special section titled the Third World Review in 1978. This section represented

a conscious effort to provide a space for Third World voices in the First World

media. In an arrangement between the editors of The Guardian and editors of

newspapers in developing countries, the latter could contribute to the Review

about their respective countries from a participantobservers standpoint,

provided they subjected themselves to The Guardians editorial control. Gauhar

saw this move only as a beginning, albeit an encouraging one; he expected it

to serve as a model for editorial partnership between the North and the South

(Gauhar, 1981: 176). The term partnership implies shared decision-making

between the gate-keepers of the First and Third World media. Gauhar sug-

gested a similar arrangement for news agency collaboration, by region and

topic. Such partnerships, in a spirit of sharing public knowledge (Gauhar,

1981: 177) valorize the Other in the domain of gate-keeping and thus restore

some autonomy to news agency media operations in developing regions.

Downloaded from http://jou.sagepub.com by Pedro Aguiar on November 11, 2008

Sosale Envisioning a new world order through journalism 387

Shared decision-making at the stage of gate-keeping changes the journalistic

power balance between the developed and the developing countries and

demonstrates a reconfigured world order at the press/media power centres,

leading to a blurring of lines between the centre and the periphery in a critical

journalistic practice.

Gauhar also observed that training programmes in the Third World

required the leadership of professional instructors from the South, and that

bringing journalists from the South to training centres in the North was both

wasteful and in many ways injurious (Gauhar, 1981: 177). For example, an

attitude towards development news as a process rather than an event needs to

be encoded in the training for evaluating newsworthiness (also Verghese,

1978); and Gauhar believed this could be achieved because journalists from

the South tended to be more knowledgeable about governmental and non-

governmental development programmes for social change in their respective

countries.

In these texts, though there were frequent references to the core, it did not

possess the centre of gravity that it enjoys in the conventional world order.

The new gate-keeping practices also suggested a re-structuration of the world

order a hermeneutic of a complex and multiple whole rather than a linear

and hierarchical system.

Public opinion and civil society

Modernization debates highlighted the need for modern mass media in

developing regions in order to build public opinion for the successful func-

tioning of a democracy. Public opinion claimed roots in the notion of an

informed public whose pulse on various issues could be detected, particularly

for election purposes, as is the case in many core nations. Public opinion study

has had a history of being identified with election and voting behaviour.

Undisputedly, these two components are vital to the effective functioning of a

democracy. However, participants of the Third World Journalists Seminar

expanded the concept from informed electorates to informed publics. They

advocated a place in the western media for the aspirations of Third World

countries and recognition of . . . cultural, political, social and economic

diversity. According to them, the image of the Other would have to be

conveyed free of ethnocentric projections and interpretations in the media

(Development Dialogue, 1981: 116, 117). Development journalism, associated

with developing regions, then translates to public or civic journalism in the

western context, where the sense of community and social responsibility

intersect to produce informed publics (Gunaratne [1998] offers an excellent

Downloaded from http://jou.sagepub.com by Pedro Aguiar on November 11, 2008

388 Journalism 4(3)

analysis of the parallels between development journalism and public journal-

ism). In this redefinition, the role of public opinion would expand con-

siderably to instil awareness and appreciation of global socioeconomic

conditions and contain the seeds to support and mobilize policy for social

change in the developing regions.

Schudsons positioning of news in modern societies is particularly helpful

in interpreting the demands of the seminar participants. The role of journal-

ism in building the modern public consciousness (Schudson, 1995: 2), of

which public opinion is a part, cannot be underestimated. News engenders a

public knowledge that, according to Schudson (1995: 3), is an omnipresent

brand of shared knowing. In fact, for him, news media should evoke empathy

and provide deep understanding so . . . citizens at large can appreciate the

situation . . . of non-elites and convey compassion that diplomats distrust . . .

as a basis for foreign policy (Schudson makes specific reference to the cases of

Sarajevo and Somalia here; p. 29). Thus, we can say that to an extent, the Third

World journalists in the seminar attempted to re-theorize the concept of

public opinion that is so intimately connected to journalism.

To re-define the term information keeping in mind the needs of commu-

nities rather than corporations and governments requires the close involve-

ment of third systems of communication (see previous discussion of Savios

idea). At the community level, these systems interpret the term information

very differently from the discussions on balanced information flow between

the developed and developing regions. According to Savio (1982), third

systems of information are in the best position to articulate and circulate

information suited to their communities needs. He accepted the existing

world communication order as a consequence of history and as an institution-

alized system of information that would continue to fulfil certain needs. But in

conceptualizing a civil society approach to information, Savio did not con-

sider a new information order to be necessarily international. Instead, he

advocated the creation of other flows and institutions based on community

communication that were not alternate information systems but existed side-

by-side with the mainstream, as part of a plural mainstream.

This final theme on the notion of public opinion and the importance of

civil society addressed audiences in the First World as a vital component in

global journalism. When media gatekeepers approach audiences as members

of a civil society rather than an index of ratings and when vital social

institutions take on the role of the media in certain instances, the symbolic

domain will reflect a new (and different) communication order. Re-imagining

a new world order based on communication thus requires going beyond

institutions and professionals and into the perceptions and opinions of the

average citizen in everyday life.

Downloaded from http://jou.sagepub.com by Pedro Aguiar on November 11, 2008

Sosale Envisioning a new world order through journalism 389

Conclusions and implications for the 21st century

This article examined some lesser-known yet seminal texts generated at a

particular point in history, during the debates about instituting a new world

communication order. It has been demonstrated that a re-imagination of a

new communication order was predicated upon the hermeneutic of a world

system or a single world order. That is, the perception and understanding of

the complex of nation-states and their arrangement in the global space

manifests itself as a single world system or order. World system and structura-

tion theories provide the conceptual explanation for both the perception and

the actual shaping of this macro social structure. As Layder (1994: 1278)

explains:

People and the products of their social activities cannot be treated [independ-

ently]. People are intrinsically involved with society and actively enter into its

constitution; they construct, support and change it because it is the nature of

human beings to be affected by, and to affect, their social environment.

To the extent that the world order was constructed as a consequence of certain

events in history, supporters of a new information order could express the felt

need for different ways of conceptualizing the world order, communication,

directionality of communication flow and so on, within the legible metaphors

of the existing world order. As Huesca and Dervin (1994: 61) explain: A

communication practice can be judged as alternative, within this framework, to

the extent that it encompasses and assumes the complex process of popular

social practices (emphasis added).

We are now left with the following questions. What are the implications

of this analysis for the 21st century? Are the issues raised in recent history

relevant now in the global era? And if so, how exactly might they be applicable

as lessons for practicing journalism and envisioning a new order today? While

definitive answers to these complex questions are not possible, we can use the

analysis of the current era of globalization as a starting point to attempt some

responses. If the information flow questions were critical for the news media

in the 1970s, they continue to be so for the present. An analysis by Boyd-

Barrett and Thussu (1993) indicates that Third World news agencies contribute

marginally to the news needs of developing regions primarily due to lack of

sufficient capital. West-based news agencies continue to operate with large

capital outlays from the centre of the world information/communication

system. One can reasonably assume then that the general tenor of information

available to mainstream media audiences in developed regions is similar to the

content in the 1970s. Gatekeepers of big media continue to respond to

relatively narrow definitions of news since the constraints within which they

operate are similar to those 25 years ago. At the same time, new media have

Downloaded from http://jou.sagepub.com by Pedro Aguiar on November 11, 2008

390 Journalism 4(3)

created new outlets for expression and new opportunities for access and

participation. In this sense, numerous instances of diffusing the centre have

manifested themselves in two ways: as alternate media in multiple locations,

and as alternate global circuits of activities and activisms connected by media

(see for example Atton, 2001 and Dowmunt, 1998). To what extent they are

successful in countering the continued hegemony of the large media systems is

difficult to conclude. Recent extended analyses of globalization (for example,

Hardt and Negri, [2000] and Harvey [2000]) point to the persistent hegemony of

global capital in the information economy. Scholars such as McChesney et al.

(1998) emphasize the continued dominance of big (now even bigger) media,

although the very recent problems with conglomerates like Vivendi Universal

hint at the beginnings of a loss of faith in big media mergers within the

transnational business community (Lohr, 2002). Barring this last new develop-

ment, the notion of diffusing the centre continues to be critical.

The composition of the audiences in the centre has changed considerably

in the last decade or so. Besides refugee populations, increasingly, analysis is

now available about the changing patterns of migratory labour, temporary

workers in the fringe economies of global metropolises and the disconnection

(and divide) between the highly paid professionals of the new knowledge

economy and their support staff hired for minimum wages (Sassen, 1998).

These observations paint a picture of a metropolitan society composed not

only of more numbers of disenfranchized groups from a class standpoint but

also diverse ethnic groups from a cultural standpoint. Factored into this

complex are significant increases in women as low-wage workers, conse-

quently gendering society in new ways. As Sassen has encapsulated this

diversity in relation to power neatly, many in the global cities with highly

concentrated populations lack the power but now have presence (p. xxi).

Besides the global metropolises, there are also rural and semi-urban popula-

tions to consider. It is all the more important in such a climate to redefine and

re-theorize the concept of public opinion as envisioned by the participants of

the Third World Journalists Seminar and re-inscribe the notion of community

into journalistic practices. Hence, changes in the present global system not-

withstanding, some lessons can be culled from the debates for re-imagining a

new (alternate?) world order.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this article was presented at the annual conference of the

International Association for Media and Communication Research, Barcelona,

Spain, 2002. The author thanks Chris Atton and the anonymous reviewers of

this manuscript for their productive feedback.

Downloaded from http://jou.sagepub.com by Pedro Aguiar on November 11, 2008

Sosale Envisioning a new world order through journalism 391

Note

1 Structuration, in a sense, is a critique of the world system theory. My thanks to

Terhi Rantanen for alerting me to the need for clarification here. World system

theory explains the international structure as derivative of economic forces,

whereas structuration, broader and more sociological in scope, incorporates the

dynamic of social change, thus giving the global structure a less determined and

a more contestatory and constitutive character. I treat world system theory as an

explanation of the existing global communication hierarchy in concrete and

tangible terms, and draw from structuration to suggest the historical possibility

of an alternative world order.

References

Appadurai, A. (1990) Technology and Reproduction of Values in Rural Western India,

in F. A. Marglin and S. Marglin (eds) Dominating Knowledge: Development, Culture,

and Resistance. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Atton, C. (2001) Approaching Alternate Media: Theory and Methodology, paper

presented at the annual convention of the International Communication Asso-

ciation, Washington, DC.

Boyd-Barrett, O. and D. Thussu (1993) NWICO Strategies and Media Imperialism: The

Case of Regional News Exchange, in K. Nordenstreng and H. Schiller (eds) Beyond

National Sovereignty: International Communication in the 1990s. Norwood, NJ:

Ablex.

Dag Hammarskjold Libraries (1983) The New World Information and Communication

Order: A Selected Bibliography. New York.

Development Dialogue (1981) Statement by the Participants in the 1975 Dag Ham-

marskjold Third World Journalists Seminar, Development Dialogue, 2: 11518.

Dowmunt, T. (1998) An Alternative Globalization: Youthful Resistance to Electronic

Empires, in D. Thussu (ed.) Electronic Empires: Global Media and Local Resistance.

London: Arnold.

Escobar, A. (1995) Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third

World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Featherstone, M. (1990) Global Culture: An Introduction, in Global Culture: Nation-

alism, Globalization and Modernity. London: Sage.

Gauhar, A. (1981) Third World: An Alternative Press, Journal of International Affairs

35(2): 16577.

Giddens, A. (1986) The Constitution of Society. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of

California Press.

Giddens, A. (1993) New Rules of Sociological Method, 2nd edn. Stanford, CA: Stanford

University Press.

Golding, P. (1977) Media Professionalism in the Third World: The Transfer of an

Ideology, in J. Curran, J. Woollacott and M. Gurevitch (eds) Mass Communication

and Society. London: Edwin Arnold.

Downloaded from http://jou.sagepub.com by Pedro Aguiar on November 11, 2008

392 Journalism 4(3)

Gunaratne, S. (1998) Old Wine in a New Bottle: Public Journalism, Developmental

Journalism, and Social Responsibility, in M. E. Roloff (ed.) Communication

Yearbook 21. Thousand Oaks, London, New Delhi: Sage.

Hall, S. (1985) The Rediscovery of Ideology: Return of the Repressed in Media

Studies, Reprint in V. Beechey and J. Donald (eds) Subjectivity and Social Relations.

Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Hardt, M. and A. Negri (2000) Empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Harvey, D. (2000) Spaces of Hope. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Huesca, R. and B. Dervin (1994) Theory and Practice in Latin American Alternative

Communication Research, Journal of Communication 44(4): 5373.

Layder, D. (1994) Understanding Social Theory. London, Newbury Park, Delhi: Sage.

Lohr, S. (2002) Vivendi Troubles Reflect Change in Investors Hopes for Big Media,

The New York Times (3 Jul.): A1.

McChesney, R., E. M. Wood and J. B. Foster (1998) Capitalism and the Information Age.

New York: Monthly Review Press.

May, C. (2002) The Information Society: A Sceptical View. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Melkote, S and L. Steeves (2001) Communication for Development in the Third World,

2nd edn. New Delhi, Thousand Oaks, London: Sage.

Righter, R. (1978) Whose News? Politics, the Press and the Third World. New York: Times

Books.

Robertson, R. (1990) Mapping the Global Condition: Globalization as the Central

Concept, in M. Featherstone (ed.) Global Culture Nationalism, Globalization and

Modernity. London: Sage.

Sassen, S. (1998) Globalization and its Discontents. New York: The New Press.

Savio, R. (1982) Communications and Development in the 1980s, IFDA Dossier

32: 759.

Schudson, M. (1995) The Power of News. Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard

University Press.

Thompson, J. (1990) Ideology and Modern Culture: Critical Social Theory in the Era of

Mass Communication. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Verghese, B. G. (1978) A Philosophy for Development Communications: The View

from India, Readings on the Relationship Between Development and Communication

1, International Commission for the Study of Communication Problems 44.

Paris: UNESCO.

Vincent, R., K. Nordenstreng and M. Traber (1999) Towards Equity in Global Commu-

nication: MacBride Update. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Wallerstein, I. (1974) Modern World System. New York: Academic Press.

Webster, F. (1995) Theories of the Information Society. London: Routledge.

Biographical notes

Sujatha Sosale teaches in the Department of Communication, Georgia State

University. She will soon be joining the Journalism faculty at the University of

Iowa.

Address: Department of Communication, Georgia State University, One Park Place

South, Suite 1040, Atlanta, GA 30303, USA. [email: ssosale@gsu.edu]

Downloaded from http://jou.sagepub.com by Pedro Aguiar on November 11, 2008

You might also like

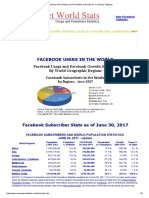

- Facebook World Stats and Penetration in The World - Facebook Statistics 2017Document5 pagesFacebook World Stats and Penetration in The World - Facebook Statistics 2017Pedro AguiarNo ratings yet

- World Directory of News Agencies Offices and CorrespondentsDocument300 pagesWorld Directory of News Agencies Offices and CorrespondentsPedro AguiarNo ratings yet

- FIPP World Magazine Trends - Special Report - Magazine MediaDocument30 pagesFIPP World Magazine Trends - Special Report - Magazine MediaPedro AguiarNo ratings yet

- Peter Brunner - News Agencies (Media Day 2004)Document15 pagesPeter Brunner - News Agencies (Media Day 2004)Pedro AguiarNo ratings yet

- Montreal, September 1968: The "Meeting of Experts" We Almost Never Heard About. Taking A Look Back at A Peculiar ReportDocument16 pagesMontreal, September 1968: The "Meeting of Experts" We Almost Never Heard About. Taking A Look Back at A Peculiar ReportPedro AguiarNo ratings yet

- NAWC - News Agencies World Congress 2016 - List of ModeratorsDocument16 pagesNAWC - News Agencies World Congress 2016 - List of ModeratorsPedro AguiarNo ratings yet

- NAWC - News Agencies World Congress 2016 - List of ParticipantsDocument6 pagesNAWC - News Agencies World Congress 2016 - List of ParticipantsPedro AguiarNo ratings yet

- Resume - Pedro Aguiar, JournalistDocument2 pagesResume - Pedro Aguiar, JournalistPedro AguiarNo ratings yet

- CV Pedro Aguiar - Journalist - EnglishDocument6 pagesCV Pedro Aguiar - Journalist - EnglishPedro AguiarNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- NABOKOV OdlomciDocument7 pagesNABOKOV OdlomcianglistikansNo ratings yet

- The Best Magazine Design - Photography, Illustration, Infographics & Digital PDFDocument345 pagesThe Best Magazine Design - Photography, Illustration, Infographics & Digital PDFUrvish Patel75% (4)

- Handcrafted Inspirations Volume 2.Document290 pagesHandcrafted Inspirations Volume 2.Andrea Dobi100% (9)

- BMJ Vancouver Style - May 2012Document7 pagesBMJ Vancouver Style - May 2012Mirza RisqaNo ratings yet

- SSC Examination Suggestion 2015Document2 pagesSSC Examination Suggestion 2015Prasun GoswamiNo ratings yet

- 3248 Notes Urdu-BDocument34 pages3248 Notes Urdu-BSher Ali86% (14)

- Stanley Gibbons 'Commonwealth & British Empire Stamp Catalogue 2007' Report and Market UpdateDocument12 pagesStanley Gibbons 'Commonwealth & British Empire Stamp Catalogue 2007' Report and Market Updatepeter smith100% (1)

- Feature & Science WritingDocument2 pagesFeature & Science WritingShane LanuzaNo ratings yet

- Works CitedDocument8 pagesWorks Citedapi-125029761No ratings yet

- Astronomy Magazine October 2013Document80 pagesAstronomy Magazine October 2013Meredith_G100% (1)

- 150 Richest Indonesians 2011Document6 pages150 Richest Indonesians 2011Hendrik Budyhartono100% (1)

- 201232627Document40 pages201232627The Myanmar TimesNo ratings yet

- Media VigilDocument112 pagesMedia Vigiljust_mail_it1429No ratings yet

- Helen KellerDocument36 pagesHelen KellerDandally RoopaNo ratings yet

- Marvel60sOnline PDFDocument227 pagesMarvel60sOnline PDFBenny Ace100% (2)

- Thinking About Purposes, Audiences, and Technologies: How Is "Writing" Defined?Document9 pagesThinking About Purposes, Audiences, and Technologies: How Is "Writing" Defined?Tyler FinleyNo ratings yet

- "The Times of India": A Study of Distribution Channel Adopted byDocument35 pages"The Times of India": A Study of Distribution Channel Adopted bytasnim voraNo ratings yet

- Time USA - 11 April 2016Document62 pagesTime USA - 11 April 2016Emma Frost100% (2)

- Fall 2012 HMH Books Adult CatalogDocument118 pagesFall 2012 HMH Books Adult CatalogHoughton Mifflin HarcourtNo ratings yet

- The Beacon - September 26, 2013Document18 pagesThe Beacon - September 26, 2013Catawba SecurityNo ratings yet

- The Hound of BaskervillesDocument149 pagesThe Hound of BaskervillesManojna NimmagaddaNo ratings yet

- The Times of India: Emerging Strategies For GrowthDocument4 pagesThe Times of India: Emerging Strategies For GrowthSankar RamNo ratings yet

- Flying Saucer Review - Janet & Colin Bord - Billy Meier 1980Document4 pagesFlying Saucer Review - Janet & Colin Bord - Billy Meier 1980Oliver HinojosaNo ratings yet

- Isaac Pitman SSH or 00 Pit MDocument350 pagesIsaac Pitman SSH or 00 Pit Mkshitijsaxena100% (2)

- Nour HatoumDocument3 pagesNour HatoumNour HamadehNo ratings yet

- SWOT Analysis For AudibleDocument7 pagesSWOT Analysis For AudibleStephen OndiekNo ratings yet

- Semi-Detailed Lesson Plan (Parts of A Newspaper) Final DemoDocument5 pagesSemi-Detailed Lesson Plan (Parts of A Newspaper) Final DemoHoney Let Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- 6 Media Planning and PromotionDocument46 pages6 Media Planning and PromotionRahul AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Brain Alchemy Masterclass PsychotacticsDocument87 pagesBrain Alchemy Masterclass Psychotacticskscmain83% (6)

- Paper. The Third Age of Political Communication Influences and FeaturesDocument16 pagesPaper. The Third Age of Political Communication Influences and FeaturesAnonymous cvgcPTfNo ratings yet