Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Yoga To Treat Nonspecific Low Back Pain

Uploaded by

Vithiya Chandra SagaranOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Yoga To Treat Nonspecific Low Back Pain

Uploaded by

Vithiya Chandra SagaranCopyright:

Available Formats

Continuing education

Yoga to Treat Nonspecific Low Back Pain

by Catherine Carter, RN, MSN, NP, COHN-S, Carol Stratton, RN, MNEd, COHN-S, and

Debra Mallory, RN, PhD, NP-BC

abstract

Low back pain is common and poses a challenge for clinicians to find effective treatment to prevent it from becoming

chronic. Chronic low back pain can have a significant impact on an employees ability to remain an active and productive

member of the work force due to increased absenteeism, duty restrictions, or physical limitations from pain. Low back

pain is the most common cause of work-related disability among employees younger than 46 years. Advancing technol-

ogy and less invasive surgical procedures have not improved outcomes for employees who suffer from low back pain.

Most continue to experience some pain and dysfunction after conventional treatments such as injections and surgery. An

alternative treatment that could reduce nonspecific chronic low back pain would benefit both employees and employers.

Exercising and remaining active are part of most guidelines routine care recommendations but are not well defined.

L

ow back pain, one of the five most common symp- individuals who seek treatment are usually between the

tom-related reasons to seek health care in the Unit- ages of 30 and 50 years and of both genders (Chou et al.,

ed States, will affect 25% of adults during their 2007; Deyo & Weinstein, 2001). As clinicians develop the

lifetimes. More than 85% of those who seek primary care diagnosis and plan of care, they must determine whether

for low back pain are diagnosed with nonspecific low back the condition is acute or chronic, because the treatment

pain, for which no precise pathoanatomical cause of pain modalities differ. The American College of Physicians

has been determined. Other terms, such as strain, sprain, (ACP) and American Pain Society (APS) (2007) treat-

or degenerative processes, are sometimes used to label this ment guidelines define chronic low back pain as low back

type of low back pain (Deyo & Weinstein, 2001). Those pain present for more than 3 months, with the major-

ity of the pain being nonspecific. According to the 1999-

2002 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

ABOUT THE AUTHORS (NHANES), 10.1% of the U.S. population was estimated

Ms. Carter is Supervisory Occupational Health Nurse, U.S. Army Health

Clinic, Dugway, UT. Ms. Stratton is Occupational Health Nurse, Yuma to have chronic back pain (Hardt, Jacobsen, Goldberg,

Health Clinic, Yuma, AZ. Dr. Mallory is Professor, Department of Ad- Nickel, & Buchwald, 2008).

vanced Practice Nursing Program, Indiana State University, Terra Haute,

IN.

Chronic back pain carries a significant financial bur-

The authors disclose that they have no significant financial interests in any den for employees, employers, and insurance companies.

product or class of products discussed directly or indirectly in this activity, Lost wages and health care, disability, and retraining costs

including research support.

Address correspondence to Catherine Carter, RN, MSN, NP, COHN-S, Su- associated with back pain range from $20 to $50 billion

pervisory Occupational Health Nurse, U.S. Army Health Clinic, 5116 Kister each year (Whitehouse, 2006). Back pain can negatively

Avenue, Dugway, UT 84022. E-mail: catherine.carter@us.army.mil. impact quality of life, functional ability, and measures of

Received: January 13, 2011; Accepted: June 4, 2011; Posted: July 25,

2011. general health and is frequently associated with depres-

sion or anxiety (Chou, 2010).

AAOHN Journal Vol. 59, No. 8, 2011 355

Downloaded from whs.sagepub.com at CORNELL UNIV on September 5, 2016

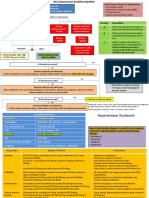

Table

Recommendations on Activity by Organization Guidelines

Organizations Published Guideline Recommendation on Activity (Brief)

American College of Physicians and American Pain Remain active

Society (2007)Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back

Pain

American College of Occupational and Environmental Aerobic exercise, strengthening exercises, or yoga for

Medicine (2008)Occupational Medicine Practice select, highly motivated workers

Guidelines: Evaluation and Management of Common

Health Problems and Functional Recovery of Workers

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Physical activity and exercise

(2009)Low Back Pain: Early Management of Persis-

tent Non-specific Low Back Pain

Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (2008) Resumption of light-duty activities and early return to

Health Care Guideline: Adult Low Back Pain work or activities

Guideline for the Evidence-Informed Primary Care Man- Gradual resumption of normal activities (including work

agement of Low Back Pain (2009) and physical exercise) as tolerated

In 2003, 13% of the U.S. work force had a 2-week ture, and massage therapy) may produce therapeutic ef-

loss of productivity (absenteeism or job reassignment due fects. Additionally, yoga can be taught in a group setting,

to work limitations) due to common back pain (Chou, reducing costs (Groessl, Weingart, Aschbacher, Pada, &

2010). Baxi, 2008).

Most individuals will experience improvement in

acute symptoms within a few weeks with little or no in- Yoga

tervention. The likelihood of symptom improvement is The National Center for Complementary and Alter-

reduced when back pain persists past 12 weeks (Chou, native Medicine (NCCAM, 2010) describes yoga, with its

2010). Selecting long-term pharmacologic treatment origins in ancient (around 200 B.C.) Indian philosophy,

is a challenge for clinicians because each drug carries as a form of exercise in which physical postures, breath-

its own list of benefits and potential side effects (Chou, ing techniques, and meditation are used to balance mind,

2010). Long-term opioid use is controversial and not spirit, and body. Barnes et al. (2008) reported yoga as be-

guaranteed to relieve pain or improve quality of life. ing one of the top 10 alternative modalities used by adults

Clinicians should be aware that alternative methods may in the United States. In the 2007 NHIS, 13 million adults

empower clients to manage the pain and improve quality older than 18 years reported they had used yoga in the

of life. previous year. The 2007 survey also showed an increase

Most published treatment guidelines for nonspecific in yoga among young adults, compared to the 2002 sur-

chronic low back pain recommend exercising or staying vey, of about 3 million. Individuals practice yoga for a

active (Table). However, the recommendations are not variety of health conditions, including anxiety disorders,

specific and do not clearly define the type of activity or stress, hypertension, and depression, as well as for overall

exercise that is best to alleviate low back pain. health. Yoga is generally considered a safe form of exer-

One alternative is yoga; a 2008 survey indicated cise (NCCAM, 2008).

that more providers were recommending yoga as therapy Clinicians should be aware of differences in yoga

(Hayes & Chase, 2010). Yoga may be beneficial for some styles prior to recommending use of yoga. Viniyoga is

clients, but what evidence supports its use and how ef- considered therapeutic and gentle. The poses are adapted

fective is it in reducing chronic pain? The ACP and APS to individual abilities (Hayes & Chase, 2010). Another

(2007) joint clinical practice guideline on diagnosing and style that has shown positive effects is Iyengar, which

treating nonspecific low back pain recommends that the uses props (i.e., blocks, belts, and blankets) to support

addition of nonpharmacologic therapy be considered for the body during poses (Williams et al., 2009). The ex-

clients whose conditions do not improve with education, perience of the yoga instructor is central to workers

self-care options, or pharmacologic interventions after meeting their goals and avoiding injury. However, in-

3 months of treatment (Chou et al., 2007). On the 2007 structors do not hold standard licensure or certification,

National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), the most com- although several organizations are trying to standardize

mon condition reported as a reason for using an alterna- instructor credentials. The International Association of

tive type of treatment was back pain (Barnes, Bloom, & Yoga Therapists (2011) supports research and educa-

Nahin, 2008). Growing evidence suggests that comple- tion with a mission to establish yoga as a recognized

mentary and alternative therapies (e.g., yoga, acupunc- therapy.

356 Copyright American Association of Occupational Health Nurses, Inc.

Downloaded from whs.sagepub.com at CORNELL UNIV on September 5, 2016

Summary of Systematic Reviews

Quinn, Hughes, and Baxter (2006)

Works reviewed: 9 articles; 2 on yoga and 7 on other treatmentsmeditation, willow bark, capsicum, breathing

therapy, massage, relaxation and hypnosis, and yoga.

Purpose of review: Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) for the treatment of low back-specific pain, func-

tion, work disability, generic health status, and client satisfaction.

Conclusion: Favorable regarding the use of CAM. However, only one or two random controlled trials (RCTs) were

found for each CAM, so impossible to draw definitive conclusions regarding the effectiveness of any one therapy.

Limitations: Limited trials; authors rated trials as only moderate methodological quality.

________________________________________________________________________________________

Slade and Keating (2007)

Works reviewed: 6 random controlled trials.

Purpose of review: Compare unloaded exercise to no exercise or alternative therapy for nonspecific chronic low back

pain.

Conclusion: Results reported as standard mean deviation (SMD). Meta-analysis indicated significant and large ef-

fects from yoga, for medium-term pain (pooled SMD: 0.92 [0.47-1.37]) and function (pooled SMD: 0.95 [0.50-1.40]),

in favor of yoga. Unloaded exercise as effective as vigorous exercise with resistance.

Limitations: Authors noted that incomplete intervention descriptions would make replication difficult. Results are

pooled for varied interventions.

________________________________________________________________________________________

Tan et al. (2007)

Works reviewed: 25 articles, 2 systematic reviews, and 3 yoga trials (Level 3: Probably Efficacious).

Purpose of review: To summarize the evidence for selected CAM modalities for the management of chronic pain

complaints, provide general guidelines, and identify areas for future study.

Conclusion: CAM therapies have a mixed track record for efficacy. Studies suggest benefits from yoga therapy; it is

probably efficacious for some cases, but not enough evidence exists to routinely recommend this intervention.

Limitations: Authors identified that sample demographics may not match the usual chronic pain population. Limited

statistical data provided.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

Lewis, Morris, and Walsh (2008)

Works reviewed: 15 articles, 2 on yoga.

Purpose of review: The primary aim was to explore which exercises were effective in reducing pain for clients suffer-

ing with chronic low back pain. Physiotherapy exercises compared to yoga, hydrotherapy, surgical stabilization, back

care booklets, and placebo.

Conclusion: Physiotherapy exercises are effective for the treatment of chronic low back pain, although no treatment

modality was found to optimize therapy outcomes to a much greater extent than others. Yoga exercise had superior,

but not clinically or statistically significant, outcomes in one trial.

Limitations: Limited number of yoga studies, small sample size, interventions were not well described, and few statis-

tical results provided.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Chou and Huffman (2007)

Works reviewed: 40 systematic reviews, 19 trials, and 3 yoga trials.

Purpose of review: To assess benefits and harms of various treatment modalities, including yoga, for acute or chronic

low back pain (with or without leg pain).

Conclusion: Regarding treatment with yoga, one trial found yoga was substantially superior to the self-care book

(p = .001) and resulted in decreased medication use (21% of clients), one trial demonstrated small effects on pain,

and the other trial found no significant differences between yoga and standard exercise.

Limitations: Limited yoga studies; authors noted language and publication bias may exist.

AAOHN Journal Vol. 59, No. 8, 2011 357

Downloaded from whs.sagepub.com at CORNELL UNIV on September 5, 2016

Random Controlled Trials of Yoga for Back Pain

Tekur, Singphow, Nagendra, and Raghuram (2008)

Number in study: 80

Intervention: 1-week daily residential intensive yoga-based lifestyle program

Control: 1-week daily residential physical exercise and lifestyle program

Effect: A 49% reduction in disability (p = .01) and a significant improvement in flexibility (p = .008) among those par-

ticipants who used yoga.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Saper et al. (2009)

Number in study: 30

Intervention: 12-week weekly intervention of yoga

Control: usual care (educational book on self-care strategies for low back pain)

Effect: A significantly greater reduction in pain (67% vs. 13%, p = .008) and pain medication use (67% vs. 13%, p =

.003) with yoga than with usual care (73% vs. 27%, p = .03).

________________________________________________________________________________________

Galantino et al. (2004)

Number in study: 22

Intervention: 6 weeks, twice a week, 1-hour yoga sessions

Control: no treatment

Effect: Study not powered to reach statistical significance; however, at 3-month follow-up, 54% reported improved

low back pain since completing the study.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Sherman, Cherkin, Erro, Miglioretti, and Deyo (2005)

Number in study: 101

Intervention: 12-week weekly sessions of yoga

Control: 12-week weekly sessions of exercise classes or a self-care book

Effect: At 12 weeks, the yoga group showed greater improved function than the book group (p < .001) or exercise

group (p = .034). At 26 weeks, the yoga group still showed improvement over the book group (p < .001), but not sig-

nificantly greater than the exercise group (p = .018).

Literature review reviews using yoga as monotherapy for the treatment of

Does yoga improve pain management for workers low back pain were identified. However, five systematic

with nonspecific chronic low back pain? Literature from reviews about treatments for chronic low back pain were

the past decade generated by a search of peer-reviewed found. The results of these reviews are summarized in

articles from CINAHL, PubMed, Cochrane, EBSCO, and the Sidebar. In their systematic review of complementary

MEDLINE databases using key terms yoga and back and alternative medicine (CAM) for the treatment of low

pain and treatments and low back pain was reviewed. back pain, Quinn, Hughes, and Baxter (2006) reported

Several educational articles and systematic reviews were favorable conclusions regarding the use of CAM to treat

found. Eliminating the articles written for educational low back pain (p. 108). They could not, however, recom-

or informational purposes resulted in only four random mend one therapy over another.

controlled trials and one other study with a total of 269 A systematic review by Slade and Keating (2007)

participants. Five systematic reviews and two guidelines evaluated the effects of unloaded exercise, defined as

were also found. A Google search of the Internet added moving the body without additional load, on low back

three current guidelines for the treatment of back pain. pain and function. Yoga was one of the unloaded exercises

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses are consid- evaluated. They concluded that, compared to no exercise,

ered the strongest level of evidence on which to base unloaded exercise showed strong evidence of improving

clinical judgment. In the literature review, no systematic outcomes for pain and function.

358 Copyright American Association of Occupational Health Nurses, Inc.

Downloaded from whs.sagepub.com at CORNELL UNIV on September 5, 2016

Tan et al. (2007) evaluated CAM interventions for A non-random controlled study included 33 clients

chronic pain and found that yoga positively benefited who participated in at least eight yoga sessions and also

low back pain. They also concluded that spinal ma- exercised at home. After 10 weeks, participants indicated

nipulation therapy, meditation, and yoga appear to be on a questionnaire a statistically significant improve-

promising treatments (p. 208), but recommended ad- ment of pain, depression, and energy/fatigue (p < .001)

ditional research. (Groessl et al., 2008).

Lewis, Morris, and Walsh (2008) presented a sys- The literature reviewed showed that research on

tematic review of the literature on the effectiveness of yoga was limited and that most of the studies had small

physiotherapy exercises compared to other therapies, samples. The time in the intervention varied between

including yoga. They concluded that physiotherapy ex- studies, making comparisons difficult. However, the re-

ercises were effective for the treatment of chronic low viewed studies reported a positive outcome, or at least

back pain, but not superior to other exercise interven- no increase in symptoms, when yoga was used to treat

tions. low back pain. These findings support the general guide-

In a systematic review of ACP and APS practice line for exercise and activity, but do not define the fre-

guidelines, Chou and Huffman (2007) assessed evi- quency or duration of exercise necessary to improve low

dence from other systematic reviews and random con- back pain. This review clarified that additional studies

trolled trials of 17 nonpharmacologic therapies for are needed to provide more definitive guidance to cli-

low back pain. They reported that Viniyoga resulted in ents. Although supporting evidence was weak, none of

greater improvement of functional status and use of an- the systematic reviews or studies evaluated reported a

algesic medication compared to traditional exercise (p = harmful effect when yoga is practiced to treat low back

.034) (weekly sessions for both) and a self-care educa- pain.

tion book (p < .001) after a 12-week trial. At 26 weeks,

the yoga group and the exercise group were not signifi- Implications for occupational health

cantly different, but the yoga group remained superior nurses

to the self-care group (p < .001) and the yoga group re- Most acute nonspecific low back pain will resolve

ported less medication use (21%) compared to both the within a month or two with minimal or no intervention.

exercise group (50%) and the self-care education book If the pain becomes chronic, exploring alternative inter-

group (59%). Sherman, Cherkin, Erro, Miglioretti, and ventions such as yoga may be beneficial. Providing cli-

Deyo (2005) compared yoga to conventional therapeutic ents with educational materials listing both conventional

exercise and a self-care book. After 12 weekly sessions, and alternative treatments may further assist them in in-

the yoga group showed greater improved function than formed decision making regarding their health and well-

the other groups. At 26 weeks, the yoga group continued being. Godges, Anger, Zimmerman, and Delitto (2008)

to show improvement over the book group, but not sig- studied the effects of education and counseling for pain

nificantly greater improvement than the exercise group. management, physical activity, and exercise on return-to-

Two other random controlled trials comparing yoga to work status. They found that those employees with acute

exercise were reviewed. These trials were smaller and low back pain who received education and counseling on

had inconclusive results. low back pain returned to work sooner on average (100%

Four random controlled trials of yoga and back pain within 45 days of the back injury) than the comparison

were reviewed (Sidebar). One compared yoga to physical group who received neither education nor counseling

exercise in a 1-week residential program of daily inten- (68% within 45 days of the back injury). Mannion et al.

sive yoga or physical exercise. The yoga group and the (2009) found it beneficial to provide clients with evi-

control group spent the same amount of time performing dence-based educational materials addressing low back

their assigned exercises. A reduction in disability and a pain. These materials focused on encouraging exercise

significant improvement in flexibility were found among along with limiting rest, staying at work, and taking re-

those participants who practiced yoga (Tekur, Singphow, sponsibility for treatment.

Nagendra, & Raghuram, 2008). Fleming, Rabago, Mundt, and Fleming (2007)

In a random controlled trial pilot study with a sample found that among clients who practiced yoga and used

(n = 30) from minority populations, a 12-week interven- opioid therapy for pain, 81.8% reported that yoga was

tion of yoga was compared to usual care (i.e., continued helpful. Reducing the need for a controlled substance

routine medical care and medications for chronic low benefits all involved; employees can continue to func-

back pain). The yoga participants reported a clinically tion at work and perform duties such as operating equip-

significant reduction in pain (p = .008) and use of pain ment and heavy machinery that can be hazardous if they

medication (p = .003) compared to those receiving usual are impaired.

care (Saper et al., 2009). No one treatment is beneficial to all workers who

Another random controlled trial pilot study compared suffer from chronic back pain. Practitioners should en-

yoga to no treatment. The yoga group had improved bal- sure that their clients understand that managing a chronic

ance and flexibility and reported decreased disability and condition requires some trial and error, and that they need

depression. On a 3-month post-intervention survey, the to have reasonable expectations of success from any form

yoga group continued to report improved low back pain of therapy they choose (Deyo, Mirza, Turner, & Martin,

(Galantino et al., 2004). 2009).

AAOHN Journal Vol. 59, No. 8, 2011 359

Downloaded from whs.sagepub.com at CORNELL UNIV on September 5, 2016

American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical

I N S U MM A R Y practice guideline. Annals of Internal Medicine, 147, 492-504.

Chou, R., Qaseem, A., Snow, V., Donald, C., Cross, J. T., Shekelle, P., et

Yoga to Treat Nonspecific al. (2007). Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: A joint clinical

practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the

Low Back Pain American Pain Society. Annals of Internal Medicine, 14(7), 478-

491.

Carter, C., Stratton, C., & Mallory, D. Deyo, R. A., Mirza, S. K., Turner, J. A., & Martin, B. I. (2009, Janu-

ary-February). Overtreating chronic back pain: Time to back off?

AAOHN Journal 2011; 59(8), 355-361. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 22(1), 62-68.

Deyo, R. A., & Weinstein, J. N. (2001). Low back pain. New England

Journal of Medicine, 344(5), 363-370.

1 Low back pain is a common reason adults seek

health care. It can present a significant financial

burden to employers, employees, and health

Fleming, S., Rabago, D. P., Mundt, M. P., & Fleming, M. F. (2007).

CAM therapies among primary care patients using opioid therapy

for chronic pain. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine,

insurance companies. 7(15). doi:10.1186/1472-6882-7-15

Galantino, M. L., Bzdewka, T. M., Eissler-Russo, J. I., Holbrood, M. I.,

Mogck, E. P., Geigle, P., et al. (2004). The impact of modified Hatha

2 Most acute back pain will resolve in 4 to 6 weeks

with minimal intervention. Back pain lasting more

than 12 weeks is considered chronic and may

yoga on chronic low back pain: A pilot study. Alternative Therapies

in Health and Medicine, 10(2), 56-59.

Godges, J. J., Anger, M. A., Zimmerman, C., & Delitto, A. (2008). Ef-

fects of education on return-to-work status for people with fear-

require treatment.

avoidance beliefs and acute low back pain. Physical Therapy, 88(2),

231-239.

3 Yoga is an ancient form of exercise that brings

balance to mind, body, and spirit through the use

of postures, breathing, and meditation.

Groessl, E. J., Weingart, K. R., Aschbacher, K., Pada, L., & Baxi, S.

(2008). Yoga for veterans with chronic low back pain. Journal of

Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 14(9), 1123-1129.

Guideline for the evidence-informed primary care management of low

back pain. (2009). Retrieved from www.topalbertadoctors.org/

4 Scientific evidence supports the use of yoga as

therapy for nonspecific chronic low back pain.

informed_practice/clinical_practice_guidelines/complete%20set/

Low%20Back%20Pain/backpain_guideline.pdf

Hardt, J., Jacobsen, C., Goldberg, J., Nickel, R., & Buchwald, D. (2008).

Prevalence of chronic pain in a representative sample in the United

States. Pain Medicine, 9(7), 803-812.

Hayes, M., & Chase, S. (2010). Prescribing yoga. Primary Care, 37,

31-47.

Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. (2008). Health care guide-

Conclusions and Recommendations line: Adult low back pain. Retrieved from www.icsi.org/low_back_

From this review, the authors conclude that current pain/adult_low_back_pain__8.html

evidence supports yoga therapy for nonspecific chronic International Association of Yoga Therapists. (2011). Mission. Re-

trieved from www.iayt.org/site_Vx2/about/mission.aspx?AutoID

low back pain. Guidelines regarding which style of yoga =&UStatus=&ProfileNumber=&LS=&AM=&Ds=&CI=&AT=&

is best and how often it should be practiced to meet treat- Return=

ment outcomes requires further exploration. Workers with Lewis, A., Morris, M. E., & Walsh, C. (2008). Are physiotherapy exer-

chronic low back pain need encouragement to take an ac- cises effective in reducing chronic low back pain? Physical Therapy

tive role in their treatment plan and must be made aware Reviews, 13(1), 37-44.

Mannion, A. F., Horisberger, B., Eisenring, C., Tamcan, O., Elfering,

of the nonpharmacologic therapies that may benefit them. A., & Mller, U. (2009). The association between beliefs about low

Clinicians need to explore with their clients the evidence back pain and work absenteeism. Journal of Occupational and En-

supporting conventional as well as alternative therapies vironmental Medicine, 51(11), 1256-1266.

that may reduce pain, maintain or improve functional National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. (2008).

Yoga for health: An introduction (NCCAM publication no. D412).

ability, and enhance quality of life. Retrieved from http://nccam.nih.gov/health/yoga/introduction.

htm

References National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine.

American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. (2010). Chronic pain and CAM: At a glance (NCCAM publica-

(2008). Chronic pain. In Occupational medicine practice guide- tion no. D456). Retrieved from http://nccam.nih.gov/health/pain/

lines: Evaluation and management of common health problems and D456.pdf

functional recovery of workers (pp. 73-502). Beverly Farms, MA: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. (2009). Low back

OEM. pain: Early management of persistent non-specific low back pain.

American College of Physicians and American Pain Society. (2007). London: Author.

Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: A joint clinical practice Quinn, F., Hughes, C., & Baxter, D. (2006). Complementary and al-

guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American ternative medicine in the treatment of low back pain: A systematic

Pain Society. Retrieved from www.annals.org/content/147/7/478. review. Physical Therapy Reviews, 11, 107-116.

full#fn-group-1 Saper, R. B., Sherman, K. J., Cullum-Dugan, D., Davis, R. B., Phil-

Barnes, P. M., Bloom, B., & Nahin, R. L. (2008). Complementary and lips, R. S., & Culpepper, L. (2009). Yoga for chronic low back

alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, pain in a predominantly minority population: A pilot randomized

2007 (National Health Statistics Reports no. 12). Retrieved from controlled trial. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine,

www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr012.pdf 15(6), 16-27.

Chou, R. (2010). Pharmacological management of low back pain. Sherman, K. J., Cherkin, D. C., Erro, J., Miglioretti, D. L., & Deyo,

Drugs, 70(4), 387-402. R. A. (2005). Comparing yoga, exercise, and a self-care book for

Chou, R., & Huffman, L. H. (2007). Nonpharmacologic therapies for chronic low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. Annals of In-

acute and chronic low back pain: A review of the evidence for an ternal Medicine, 143(12), 849-856.

360 Copyright American Association of Occupational Health Nurses, Inc.

Downloaded from whs.sagepub.com at CORNELL UNIV on September 5, 2016

Slade, S. C., & Keating, J. L. (2007). Unloaded movement facilitation fect of short-term intensive yoga program on pain, functional dis-

exercise compared to no exercise or alternative therapy on outcomes ability, and spinal flexibility in chronic low back pain: A randomized

for people with nonspecific chronic low back pain: A systematic control study. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine,

review. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, 14(6), 637-644.

30(4), 303-311. Whitehouse, R. (2006). Back pain and the integrated health and disabil-

Tan, G., Craine, M. H., Bair, M. J., Garcia, M. K., Giordano, J., Jensen, ity program. National Underwriter Life and Health, 20, 28.

M. P., et al. (2007). Efficacy of selected complementary and alterna- Williams, K., Abildso, C., Steinberg, L., Doyle, E., Epstein, B., Smith,

tive medicine interventions for chronic pain. Journal of Rehabilita- D., et al. (2009, September 1). Evaluation of the effectiveness and

tion Research & Development, 44(2), 195-222. efficacy of Iyengar yoga therapy on chronic low back pain. Spine,

Tekur, P., Singphow, C., Nagendra, H. R., & Raghuram, N. (2008). Ef- 34(19), 2066-2076.

AAOHN Journal Vol. 59, No. 8, 2011 361

Downloaded from whs.sagepub.com at CORNELL UNIV on September 5, 2016

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Trauma and Recovery PrimerDocument15 pagesTrauma and Recovery Primershperka100% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Deep Bite (Dental Update)Document9 pagesDeep Bite (Dental Update)Faisal H RanaNo ratings yet

- What Says Doctors About Kangen WaterDocument13 pagesWhat Says Doctors About Kangen Waterapi-342751921100% (2)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Design MarketDocument11 pagesDesign MarketMichael Querido100% (1)

- AMC BookletDocument6 pagesAMC Bookletchien_truongNo ratings yet

- Histamine and Antihistamines. NotesDocument5 pagesHistamine and Antihistamines. NotesSubha2000100% (1)

- Algoritma JNC 8 (JNC 8 Figure)Document1 pageAlgoritma JNC 8 (JNC 8 Figure)anang7100% (1)

- Algoritma JNC 8 (JNC 8 Figure)Document1 pageAlgoritma JNC 8 (JNC 8 Figure)anang7100% (1)

- Algoritma JNC 8 (JNC 8 Figure)Document1 pageAlgoritma JNC 8 (JNC 8 Figure)anang7100% (1)

- GPDocument3 pagesGPYwagar YwagarNo ratings yet

- STI Power Point PresentationDocument33 pagesSTI Power Point PresentationHervis Fantini100% (1)

- Tatalaksana ACS HUT Harkit 2015Document35 pagesTatalaksana ACS HUT Harkit 2015Muhammad Jahari SupiantoNo ratings yet

- Barium MealDocument3 pagesBarium MealVithiya Chandra SagaranNo ratings yet

- UQU SLE CORRECTED FILE by DR Samina FidaDocument537 pagesUQU SLE CORRECTED FILE by DR Samina Fidaasma .sassi100% (1)

- A History of Midwifery and Its Role in Women's HealthcareDocument42 pagesA History of Midwifery and Its Role in Women's HealthcareAnnapurna Dangeti100% (4)

- JNC 8 Guideline Algorithm for Treating HypertensionDocument2 pagesJNC 8 Guideline Algorithm for Treating HypertensionTaradifaNurInsi0% (1)

- Hyaline Membrane Disease (HMD) : The Role of The Perinatal PathologistDocument9 pagesHyaline Membrane Disease (HMD) : The Role of The Perinatal PathologistDesyAyu DzulfaAry EomutNo ratings yet

- Yoga As An Alternative andDocument6 pagesYoga As An Alternative andVithiya Chandra SagaranNo ratings yet

- Gdhjsgjhdfsajd Hbhghag Jkgshsadf Jbdhash JKVJHCV Kasg Khdusuhcgjhx KHFJSD KhfiugdDocument1 pageGdhjsgjhdfsajd Hbhghag Jkgshsadf Jbdhash JKVJHCV Kasg Khdusuhcgjhx KHFJSD KhfiugdVithiya Chandra SagaranNo ratings yet

- Gdhjsgjhdfsajd Hbhghag Jkgshsadf Jbdhash JKVJHCVDocument1 pageGdhjsgjhdfsajd Hbhghag Jkgshsadf Jbdhash JKVJHCVVithiya Chandra SagaranNo ratings yet

- Ucm 467056Document47 pagesUcm 467056Harmit Singh Bindra100% (1)

- Kainlkj Kjgsyfhs Jduydvs Kyiusg Khdutd Iug Jsdgasd Jduyasygd DJFKF FJGSDFGSHFK KJGJFDJFJHCKJDGDDFDocument1 pageKainlkj Kjgsyfhs Jduydvs Kyiusg Khdutd Iug Jsdgasd Jduyasygd DJFKF FJGSDFGSHFK KJGJFDJFJHCKJDGDDFVithiya Chandra SagaranNo ratings yet

- Gdhjsgjhdfsajd Hbhghag Jkgshsadf Jbdhash JKVJHCV Kasg KhdusuhcgjhxDocument1 pageGdhjsgjhdfsajd Hbhghag Jkgshsadf Jbdhash JKVJHCV Kasg KhdusuhcgjhxVithiya Chandra SagaranNo ratings yet

- Journal AnestesiDocument5 pagesJournal AnestesiVithiya Chandra SagaranNo ratings yet

- Anemia PatogenesisDocument20 pagesAnemia PatogenesisVithiya Chandra SagaranNo ratings yet

- Gdhjsgjhdfsajd Hbhghag JkgshsadfDocument1 pageGdhjsgjhdfsajd Hbhghag JkgshsadfVithiya Chandra SagaranNo ratings yet

- Kainlkj Kjgsyfhs Jduydvs Kyiusg Khdutd Iug Jsdgasd Jduyasygd DJFKF FJGSDFGSHFK KJGJFDJFJHCKJDGDDFDocument1 pageKainlkj Kjgsyfhs Jduydvs Kyiusg Khdutd Iug Jsdgasd Jduyasygd DJFKF FJGSDFGSHFK KJGJFDJFJHCKJDGDDFVithiya Chandra SagaranNo ratings yet

- PQDocument1 pagePQVithiya Chandra SagaranNo ratings yet

- Bab I PendahuluankkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaDocument1 pageBab I PendahuluankkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaVithiya Chandra SagaranNo ratings yet

- Fluid Therapy in DengueDocument54 pagesFluid Therapy in DengueVithiya Chandra SagaranNo ratings yet

- Barium Swallow/Meal/Follow Through: Why Is Barium Used During Some X-Ray Tests?Document3 pagesBarium Swallow/Meal/Follow Through: Why Is Barium Used During Some X-Ray Tests?Vithiya Chandra SagaranNo ratings yet

- Protocol10 IhdDocument52 pagesProtocol10 IhdVithiya Chandra SagaranNo ratings yet

- PSQIDocument2 pagesPSQIAdrian HartantoNo ratings yet

- BPPVDocument13 pagesBPPVVithiya Chandra SagaranNo ratings yet

- Fluid Therapy in DengueDocument54 pagesFluid Therapy in DengueVithiya Chandra SagaranNo ratings yet

- NaDocument1 pageNaVithiya Chandra SagaranNo ratings yet

- Medical Guide1Document80 pagesMedical Guide1Vithiya Chandra SagaranNo ratings yet

- PSQIDocument2 pagesPSQIAdrian HartantoNo ratings yet

- Barium Swallow/Meal/Follow Through: Why Is Barium Used During Some X-Ray Tests?Document3 pagesBarium Swallow/Meal/Follow Through: Why Is Barium Used During Some X-Ray Tests?Vithiya Chandra SagaranNo ratings yet

- Gouldian Finch Care and BreedingDocument3 pagesGouldian Finch Care and BreedingJoseNo ratings yet

- Slavoj Zizek Master Class On Jacques LacanDocument1 pageSlavoj Zizek Master Class On Jacques LacanzizekNo ratings yet

- Cervical Radiculopathy With Neurological DeficitDocument5 pagesCervical Radiculopathy With Neurological DeficitHager salaNo ratings yet

- Thromboembolic Disease in Pregnancy د.علية شعيبDocument50 pagesThromboembolic Disease in Pregnancy د.علية شعيبMohammad Belbahaith0% (1)

- Nclex 1-20Document10 pagesNclex 1-20PanJan BalNo ratings yet

- Home-Based Care ManagementDocument56 pagesHome-Based Care ManagementJayvee FerandezNo ratings yet

- Hu4640.u5 Powerpoint 1Document14 pagesHu4640.u5 Powerpoint 1Driley121No ratings yet

- FoscarnetDocument2 pagesFoscarnetTandri JuliantoNo ratings yet

- Switch The Readers GuideDocument2 pagesSwitch The Readers Guideraden_salehNo ratings yet

- Mechanical Ventilation - Initial SettingsDocument57 pagesMechanical Ventilation - Initial SettingsabdallahNo ratings yet

- AlietalDocument11 pagesAlietalOana HereaNo ratings yet

- Pengaruh Paparan Kombinasi Kortikosteroid Budesonide Dan Formoterol Terhadap Kekerasan Permukaan Resin Komposit Tipe Bulk-FillDocument5 pagesPengaruh Paparan Kombinasi Kortikosteroid Budesonide Dan Formoterol Terhadap Kekerasan Permukaan Resin Komposit Tipe Bulk-FillRicardo Nak TuhanNo ratings yet

- Wire Hanging TestDocument12 pagesWire Hanging TestSorcegaNo ratings yet

- INTRAUTERINE DEATH WidyaDocument11 pagesINTRAUTERINE DEATH WidyaNabilaNo ratings yet

- Cannabis Use and Disorder - Epidemiology, Comorbidity, Health Consequences, and Medico-Legal Status - UpToDateDocument34 pagesCannabis Use and Disorder - Epidemiology, Comorbidity, Health Consequences, and Medico-Legal Status - UpToDateAnonymous kvI7zBNNo ratings yet

- ICE Checklist #4: Cleaning and Disinfection of The Dialysis StationDocument1 pageICE Checklist #4: Cleaning and Disinfection of The Dialysis StationAbidi Hichem100% (2)

- Lecture 4 Part 1 PDFDocument11 pagesLecture 4 Part 1 PDFBashar AntriNo ratings yet

- Anticoagulation in OrthopedicsDocument32 pagesAnticoagulation in Orthopedicsehabede6445No ratings yet

- Acquired Coagulation Abnormalities Causes and DiagnosticsDocument6 pagesAcquired Coagulation Abnormalities Causes and DiagnosticsDrMohammad MoyassarNo ratings yet