Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Abnormal Philosophy

Uploaded by

Sandeep SharmaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Abnormal Philosophy

Uploaded by

Sandeep SharmaCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Philosophy, Inc.

Derrida on Language, Being, and Abnormal Philosophy

Author(s): Richard Rorty

Source: The Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 74, No. 11, Seventy-Fourth Annual Meeting American

Philosophical Association, Eastern Division (Nov., 1977), pp. 673-681

Published by: Journal of Philosophy, Inc.

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2025769 .

Accessed: 23/03/2013 03:56

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Journal of Philosophy, Inc. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal

of Philosophy.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 14.139.240.36 on Sat, 23 Mar 2013 03:56:59 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE PHILOSOPHY OF JACQUES DERRIDA 673

ter or presence which, without presuppositions of any sort, serves as

the basis of all real meaning-if this idea breaks down under scru-

tiny and becomes unintelligible, then the concept of difference,

putting off or deferring this encounter, is also unintelligible. If

Derrida succeeds in deconstructing his target, he thereby under-

mines the intelligibility of his own attack, since he has appropri-

ated his weapons from the armory of the tradition to be decon-

structed. He leaves me, then, not knowing where I would be if I

were to agree with him.

If we proceed to peel off further layers we find that to insist on

the integrity of writing, to insist that it is "essentially" and in a

certain way already there from the beginning, is to attack the foun-

dations of ethnocentrism, of logocentrism, of phonocentrism, of

metaphysics, and of the "scientificity of science." Derrida has mo-

mentous issues in hand. Grammatology is suggested as a science to

pursue them. But since no ordinary conception of writing will

suffice, no ordinary conception of grammatology can be intended.

In the end, when we survey the ground that Derrida would have

cleared by his call for us to recognize the full honor and priority

of writing, we find no metaphysics, no logic, no linguistics, no

semantics, and no grammatology left to carry on, but only the bril-

liant scholarly mischievousness.

NEWTON GARVER

State University of New York at Buffalo

DERRIDA ON LANGUAGE, BEING, AND

ABNORMAL PHILOSOPHY *

O NE can see Derrida as a philosopher of language whose

work parallels the later Wittgenstein's, or as a disciple of

Heidegger striving to outdo his master, or as a writer who

is helping us to see philosophy as a kind of writing rather than

a domain of quasi-scientific inquiry. In the three sections of this

necessarily brief paper, I shall say something about each alterna-

tive interpretation.

* To be presented in an APA symposium on The Philosophy of Jacques

Derrida, December 30, 1977. Newton Garverwill be co-symposiast,and Marjorie

Grene will comment; see this JOURNAL, this issue, 663-673 and 682, respectively.

I am indebted to Marjorie Grene and to David Hiley for comments on an

earlier version.

This content downloaded from 14.139.240.36 on Sat, 23 Mar 2013 03:56:59 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

674 THE JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY

1. LANGUAGE

In a very clear and succinct exposition of Derrida's early work on

Husserl, Newton Garver 1 divides the many philosophers who

would like to "found" language on "logic" (practically everybody

from Plato through Ramus to the early Wittgenstein) from those

few (e.g., Rousseau, Peirce) who would "found" it on rhetoric. The

latter are those who say, with the later Wittgenstein, that "only in

the stream of life does an expression have meaning." Garver neatly

sums up Derrida's role in this debate as follows:

Derrida's penetrating consideration and ultimate rejection of the

basic principles of Husserl'sphilosophy of language is the historical

analogue of Wittgenstein's later consideration and rejection of his

early work....

... the core of Derrida's analysis, or "deconstruction,"is a sus-

tained argumentagainst the possibility of anything pure and simple

which can serve as the foundation of the meaning of, signs (xxii).

I think that this description is exact. However, in more recent

works Derrida has taken several steps away from the notion of

"founding" language, or the meaning of signs, on "rhetoric" or on

anything else. But, just as in the Philosophical Investigations it is

never very clear whether we are getting a new philosophy of lan-

guage (one in which "social practice" plays the role once played

by "picturing the world") or instead getting a protest against the

very idea of "philosophy of language," so the same point is often

unclear in Derrida. Sometimes he talks as if there were some com-

mon project (Heaven knows what) on which he and Condillac,

Humboldt, Saussure, Chomsky, Austin et al. were engaged, and as

if he had arguments for the superiority of his own views over

theirs. At other times, he seems to disdain internal criticism of his

competitors, and simply exhibits the way in which each of them

commits the great sin of the Western intellectual tradition-"logo-

centrism," the doctrine of "the primacy of the spoken word," what

Heidegger called "the metaphysics of presence." I think that his

attempts at internal criticism usually miss the mark, and that he

indeed does not share a common subject with those he discusses.2

His real target is the notion of philosophy of language as a quest

for "foundations," as an inquiry that will tell us "how meaning is

possible" or "how language hooks up with the world." In his latest

work, he seems to me to have, mercifully, got away from the pre-

I Preface to Derrida, Speech and Phenomenon and Other Essays in Husserls

Theory of Signs, David B. Allison, trans. (Evanston,Ill.: Northwestern, 1972).

2See John Searle's recent exasperated dissection of Derrida's treatment of

Austin in Glyph, I (1977): 198-208.

This content downloaded from 14.139.240.36 on Sat, 23 Mar 2013 03:56:59 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE PHILOSOPHY OF JACQUES DERRIDA 675

tense that he is doing correctly what other philosophers of lan-

guage have done incorrectly.

Though Derrida should not be thought of as making contribu-

tions to semanticsor to the philosophy of linguistics, his attack on

foundational projects chimes nicely with the skepticism of others

about philosophy of language as a new sort of "firstphilosophy"-

a discipline that will do for us what epistemologytried and failed

to do.3 Consider, for example, Davidson's attempt to separate off

the good, modest, empirical,Fregean project of describingthe logi-

cal forms of English sentences (i.e., classifyingEnglish expressions

so as to enable us to state their truth conditions within the frame-

work of quantification theory) from the bad, "transcendental,"

epistemologicallyoriented projects of Carnap, Russell, and even

Quine.4Derrida has nothing against the former project but, obvi-

ously, a great deal against the latter. A similar distrust of such

foundational enterprisesis shown by Hilary Putnam, in his recent

recantation of his own earlier "metaphysicalrealism." That sort

of realismwas, roughly, an attempt to develop a philosophicaldoc-

trine of word-worldrelationships that would supply "theory-inde-

pendent" notions of truth and referenceable to "keep us in touch

with the real." Putnam's more recent view, which Derrida would

applaud, is that any such attempt can at most give us an internal,

naturalistic, empirical, self-reflexiveaccount of the success of in-

quiry-rather than the desired escape to a transcendentalstand-

point from which we can judge the fit between our words and a

theory-freeworld.5

I doubt that there is more to such Derridian slogans as "There

is nothing outside the text" 6 than this same point. In more general

terms, the point is that we cannot, merely by going linguistic, do

5 This is a notion found, e.g., in Michael Dummett, Frege's Philosophy of

Language (London: Duckworth, 1973),p. 669.

4 See "Truth and Meaning,"SynthesexviI, 3 (September1967): 304-323, p. 316

on the "adventitious philosophical puritanism" which has been mingled with

Frege'sproject For a more general criticism of what I am calling "transcenden-

tal" projects, see Davidson's attack on the "scheme-contentdistinction," "On

the Very Idea of a Conceptual Scheme," Proceedings of the American Philo-

sophical Association,xLvii (1973/4): 5-20. I discuss this attack in "Transcenden-

tal Arguments,Self-Reference,and Pragmatism,"forthcomingin the proceedings

of the Bielefeld symposium on transcendental arguments, and in "The De-

transcendentalizingof Analytic Philosophy" forthcoming in Neue Hefte fuir

Philosophie.

5See "Realism and Reason," forthcoming in Proceedings of the American

Philosophical Association,xix (1976/7).

"Il n'y a pas de hors-texte." Jacques Derrida, Of Grammatology,Gayatri

ChakravortySpivack,trans. (Baltimore:Johns Hopkins, 1976), p. 158.

This content downloaded from 14.139.240.36 on Sat, 23 Mar 2013 03:56:59 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

676 THE JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY

what Descartes and Kant failed to do-get outside of all our rep-

resentations to a standpoint from which the legitimacy of those

representations can be judged. Derrida's usefulness, in the context

of recent philosophy of language, is not to "bring to bear the in-

sights of an alternative tradition" upon the problems of semantics,

but simply to help us see the continuity between hopeless contem-

porary attempts to "found" language (or thought, or representa-

tion, or inquiry, or whatever else we feel nervous about), and hope-

less past attempts to do the same thing.7 (This is not, however, to

say that the serious deconstructive work has already been done on

our serious side of the Channel, leaving it for Derrida and his

friends to provide merely some light-minded historical commen-

tary. Anglo-American philosophy has been repeating the history it

has been refusing to read, and we need all the help we can get to

break out of the time capsule within which we are gradually seal-

ing ourselves.)

II. BEING

It is less artificial to view Derrida as attempting to kill off the

looming father figure of Heidegger than to see him as making "con-

tributions to the philosophy of language." Derrida sees Heidegger's

account of the Western philosophical tradition as pretty much

right, but he thinks that Heidegger himself was victimized by that

tradition, and specifically by the need to ask "the question about

Being." Just as most contemporary readers of Kant wanted to have

"Kant without the Ding-an-sich," so most admirers of Heidegger

would now like to have "Heidegger without the Seinsfrage." Derrida

is remarkably successful in giving us just that. His attitude toward

Heidegger is summed up in a passage warning us against attempt-

ing anything more than the deconstruction of the tradition, against

looking for an upbeat ending to the project of closing down the

West, against converting one's latest deconstructive project into a

methodology for some new constructive effort to reach what, since

Plato, we have always sought:

There will be no unique name, not even the name of Being. It must

be conceivedwithout nostalgia; that is, it must be conceived outside

the myth of the purely maternal or paternal language belonging to

the lost fatherlandof thought. On the contrary,we must affirmit-

in the sense that Nietzschebrings affirmationinto play (met I'affirma-

tion en jeu), with a certain laughter and with a certain dance.8

7 See Of Grammatology,p. 6, for Derrida's diagnosis of the "linguistic turn"

as the last, destined, doomed, defensive movement of the Western tradition.

8 From the essay "Diff~rance,"in Speech and Phenomenon, p. 195.

This content downloaded from 14.139.240.36 on Sat, 23 Mar 2013 03:56:59 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE PHILOSOPHY OF JACQUES DERRIDA 677

The "it" in this passage refers to his term "diffirance" which.

(a) signifies the difference between a text and what it means, a

difference of which, for Derrida, Heidegger's "ontological differ-

ence" between beings and Being is a sort of special case; (b) ex-

presses "what stands opposed to the text of Western metaphysics,"

the opposite of 'presence', where that is the most general name of

what the Platonic tradition wanted-the epiphany of the simple

elements (Ideas, sense-data, meanings) which are the foundations

of everything else; (c) is a deliberately misspelled French word

produced by altering the word for "difference"-diffdrence-by a

single unpronounced letter, in order to emphasize that he has con-

structed something "which is not a name, which is not a pure nom-

inal unity, and continually breaks up in a chain of different sub-

stitutions," and that "there is nothing kerygmatic about this 'word'

so long as we can perceive its reduction to a lower-case letter" (159).

The idea is that any attempt to do what Heidegger wanted to

do-to get out from under the tradition, to emerge into a clearing

lighted by Being-will fail, because every statement of the attempt

can only be in the terms which the tradition created for us. So,

Derrida thinks, maybe all that will help are verbal tricks, fake

etymologies, typographical gimmicks, puns, allusions, dirty jokes,

what Kierkegaard called "a certain nimble dancing in the service

of thought." The trouble with the "question about Being" was that

it invited serious and methodical reflection. But this will not work,

for as Derrida says:

The fact remains that Being which is nothing, which is not a being,

cannot be said, cannot say itself, except in the ontic metaphor....

And if Heideggerradicallydeconstructedthe authorityof the present

over metaphysics,it was in order to lead us to think the presenceof

the present. But the thought of this presence only metaphorizes,by

a profound necessitywhich cannot be escaped by a simple decision,

the language it deconstructs.9

Let me try to put this in un-Heideggerian language. Suppose you

start by seeing the philosophical problems of your day as increas-

ingly pseudo-, and then you dig back into the past to find out who

drew the picture that holds captive both you and the authors of

those problems. You may finally decide that it goes all the way back

to Plato. At that point you may think that there is another pic-

ture-the one that shows things as they are-which you could

9"The Ends of Man," Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, xxx, I

(September1969): 31-57, p. 53.

This content downloaded from 14.139.240.36 on Sat, 23 Mar 2013 03:56:59 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

678 THE JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY

glimpse if you could only escape the influence of Plato's termino

ogy and presuppositions. But this is a mistake. Plato's ghost is sti:

making you think in terms of right pictures and wrong picture

better and worse perspectives, more and less accurate represents

tions, better and worse positions from which to view time an,

eternity. The tradition of Western metaphysics is just the tradition

of assuming that the cure for a bad picture is a better picture-

more complete and rigorously worked-out Weltanschauung. A

long as you think that some philosopher is going to come up wit]

the necessary terminology to state and criticize the presupposition

of the tradition, you are still as badly off as you were before. Whel

you pass this stage, you may start looking around for a mystic, o

a Zen master, or the later Heidegger, to take you away from al

the terminologies and to the heart of silence. There, perhaps, yol

may yet hear the voice of Being. But that won't work either. I

Being had a message to get across, it would have to use Platoni

jargon when it talked to you. What else would you understand

So there is nothing, Derrida concludes, save perhaps the dance a

the superman at the end of Zarathustra:

[The superman's]laughterwill then breakout towardsa return which

will no longer have the form of the metaphysicalrepetition of hu-

manism. Moreover,it will undoubtedlynot take the form, "beyond"

metaphysics,of the memorial or of the guard of the sense of the

being, or the form of the house and the truth of Being. He will

dance, outside of the house, this "aktive Vergeszlichkeit,"this active

forgetfulness(ibid. 57; translationchangedsomewhat).

In Derrida's most recent work, this dance takes the form of end

less plays with words, plays directed toward making us see word

as words rather than as signs, as inscriptions rather than vehicle

of communication, as anything rather than bearers of reference an(

truth. If one finds the fact, e.g., that the French often pronounce

"Hegel" as if it were aigle-the French for "eagle" 10Oof little

interest, one will not be likely to watch the dance for long. But i

is, I think, clear why it is being danced. It is because Derrid;

thinks that the ability to see writing as writing is what we need tc

break the grip of the notion of representation, of getting thing.

accurately pictured. If Heidegger was right about Plato anc

Derrida is right about Heidegger, then this notion cannot, indeed

be shaken off by any less extravagant means.

'o Glas (Paris: Editions Galilee, 1974), p. 7. See the discussion of this book b

Geoffrey Hartman, "Monsieur Texte," parts I and II, The Georgia Review

xxxx: 759-797, xxx: 169-197, especially the section called "Pinking Philosophy,'

in connection with Derrida'ssexy metaphilosophy.

This content downloaded from 14.139.240.36 on Sat, 23 Mar 2013 03:56:59 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE PHILOSOPHY OF JACQUES DERRIDA 679

III. ABNORMAL PHILOSOPHY

I can perhaps explain what I mean by "seeing writing as writing"

by proceeding to my third topic: the kind of philosophy that

Derrida exemplifies. It is abnormal philosophy, by contrast with

that sense of 'normal' in which Kuhn speaks of "normal" science.

Normal inquiry requires common problems and methods, profes-

sional and institutional discipline, consensus that certain results

have been achieved. Abnormal inquiry-called "revolutionary"

when it works and "kooky" when it does not-requires only genius.

Kant was both the first professionalized philosopher and the last

great philosopher who thought that philosophy might be put "on

the secure path of a science." After Kant philosophy split into two

sorts. There was the kind that still wanted what Kant had wanted

-problems to be solved and agreement on what it would take to

solve them. Logical empiricism and "classical" Husserlian phenom-

enology were both examples of this kind. Then there was the kind

that began with Hegel's Phenomenology-the kind in which one

does not solve problems but rather overcomes predecessors. Devo-

tion to that paradigm produces what we Anglo-Americans think of

as the kookiness of "Continental" philosophy. (Both these terms

obviously have ideological rather than geographical senses.) The

mark of that kind of philosophy is that it worries about people

rather than propositions. Have I, the Continental philosopher asks

himself, seen through, transcended, castrated, or otherwise disposed

of, Nietzsche? Marx? Freud? Wittgenstein? Heidegger? Derrida? It

is as if to deal with a philosopher were somehow different from

dealing with his statements. It is as if one did philosophy not by

presenting arguments against one's predecessors' views, but by vi-

olent and erotic struggle with one's images of them. From the neo-

Kantian standpoint-the standpoint of normal philosophizing-

this looks like a confusion of philosophy with literature. It is in-

telligible that a young novelist wishes to outdo Proust or Nabokov

without being able to specify in advance what would count as

doing so. But if a normal young physicist or philosopher proposes

to outdo a predecessor, it is the man's statements that are chal-

lenged rather than the man. What might count as an "important

result" of normal inquiry is determined in advance, but not what

will count as an important novel or an important poem or an im-

portant piece of "Continental" philosophy.

Crudely, then, neo-Kantian "normal" philosophy wants to be a

science, whereas Continental philosophy is content to be a kind of

writing, a genre defined by neither subject nor method nor insti-

This content downloaded from 14.139.240.36 on Sat, 23 Mar 2013 03:56:59 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

68o THE JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY

tutional affiliation, but only by an enumeration of the mighty dead.

Just as English poetry is not verse written in English, but what one

writes after reading Milton, Wordsworth, Shelley, Yeats . . ., so

philosophy of the non-Kantian sort is not a certain "approach to

the problems of philosophy," but what one writes after reading

Plato, Kant, Hegel, Nietzsche, Freud.... So when Derrida asks us

to see writing as writing he is asking us to stop construing abnor-

mal philosophy (and, indeed, all writing that is not mere "writing

up" of the results of normal inquiry) as Kant construed it: viz., as

at best just fun and games ("purposiveness without purpose"), or

at worst failed and self-deceptive attempts to attain the secure path

of a science. Derrida thinks that as long as we keep these Kantian

spectacles on we shall be unable to read,1' and that we shall have

them on as long as we ask of any given piece of writing, "But what

is it trying to say?" The dead hand of Plato will lie heavy on us

just so long as we construe words as representations, so long as we

view language as a scheme for representing arrangements between

beings (or even as a device for bringing Being itself before our eyes).

But still, one can reasonably ask, could one not grasp, and even

embrace, this conception of philosophy as a kind of writing, with-

out all of Derrida's tricksy puns and typographical innovations?

Why does it help to rub our noses in the shapes of the letters on

the page, our ears with the ways words sound when mispronounced?

It helps, I think, because it helps us to stop seeing what philos-

ophers have written as windows opening upon the world, and helps

us see them as talking about each other-about each other's words,

not about each other's views of the surrounding landscape. It helps

us see their works as networks of allusion rather than occasions of

revelation. Why should we want to view them that way? Because,

roughly, to view them in any other way is to fall back on the ques-

tion "What do philosophers have to tell us?" That, in turn, inev-

itably leads us back to the transcendental standpoint-to seeing

philosophy as that branch of inquiry which concerns itself with

the nature of representation and explains to us how the intellect

strips off essence, Subject unites with Object, language grapples

world. If we are to escape the captivity of that picture, the picture

that Kant built into the normal self-image of our discipline, we

have to become skeptical about the notion of representation itself,

in a way which only the most deliberately abnormal attitude to-

ward writing can make possible. We must question simultaneously

the notion that philosophy is an inquiry into representation, and

the notion that "representation" is a useful concept.

11 Cf. Grammatology, p. 46.

This content downloaded from 14.139.240.36 on Sat, 23 Mar 2013 03:56:59 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE PHILOSOPHY OF JACQUES DERRIDA 68i

I shall end by offering a further justification for my choice of

the term 'abnormal'. The Kantian notion of philosophy is of some-

thing that might some day be finished, for all the problems might

some day be solved. On the alternative conception there can no

more be a last page of the journal of philosophy than there can be

a last novel. Inquiry into a subject can end, but there can be

no end of writing about people who have written about people

who .. . . But this prospect of never achieving anything final, of

always being at the mercy of posterity'sdeconstructivereinterpre-

tations, is repugnant to the normal philosophical mind. It repels,

Derrida thinks, for good Freudian reasons. Normal inquiry is like

normal male sexuality-it has a direction, a point, a central thrust.

It leads to results, it has institutional guarantees,it knows when

it has succeeded.Abnormal philosophy, writing that is just more

writing, rather than preparationfor an epiphany which will make

further writing unnecessary,is as "undisciplined"as masturbation

-or, more generally,as the sort of abnormalsexuality that lives in

fantasiestoo thrilling to be actualizedor ended.12For the tradition

that startswith the Phaedrus,writing is foreplay at best. To end-

or even to soften-that tradition, Derrida thinks, we shall have to

see it as Freud helps us see it. In the end, Derrida'smost important

work may consist in his Freudian naturalizationof metaphilosophy

rather than in his reinforcementof Wittgenstein or his aufhebung

of Heidegger. He is the first professionalphilosopher to have used

Freudiannotions to talk about philosophy with Freud'sown light-

heartedness-the first to use them nonreductionisticallyand play-

fully. Seeing Plato and the Western tradition as logocentricbecause

phallocentricmay be just what we need to help us avoid the con-

descendingpomposityof the normal question about abnormalwrit-

ing: "But just what is it trying to say?"

RICHARDRORTY

Princeton University

12 See Derrida on Rousseau on the connections between perversion,masturba-

tion, and writing (Grammatology,pp. 141-164). Note also his constant use of

sexual imagery (e.g., dissemination)to exhibit the differencebetween speech and

writing. The reader who finds all this too far-fetched is asked to ponder the

connections between (a) the use of 'hard' and 'soft' to qualify 'subject','science',

'nose', 'philosophy', and 'argument'; (b) the fact that women (and unathletic

male homosexuals) were traditionally thought best adapted to soft subjects;

(c) Plato's distinction between hard-edged Being and amorphous Becoming;

(d) Plato's exhortations to mathematics,muscle-building,and military music; (e)

Plato's discussion of writing in the Phaedrus. This last topic is discussed by,

Derrida in his hilarious "Plato's Drugstore" r"La Pharmacie de Platon" in

Marges de la Philosophie (Paris: Editions Minuit, 1972), forthcoming in Fn4lisI4

translationfrom Harvard University Press].

This content downloaded from 14.139.240.36 on Sat, 23 Mar 2013 03:56:59 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- TENSESDocument11 pagesTENSESSandeep SharmaNo ratings yet

- Umberto Eco - Experiences in TranslationDocument146 pagesUmberto Eco - Experiences in TranslationJocaCarlinde100% (16)

- Time Table Dec To Jun 18Document1 pageTime Table Dec To Jun 18Sandeep SharmaNo ratings yet

- Collaborative Learning and Iranian EFL Learners' Vocabulary Improvement Through Snowball and Word-Webbing TechniquesDocument10 pagesCollaborative Learning and Iranian EFL Learners' Vocabulary Improvement Through Snowball and Word-Webbing TechniquesSandeep SharmaNo ratings yet

- Sfu221 lecEnglishAllophones PDFDocument2 pagesSfu221 lecEnglishAllophones PDFSandeep SharmaNo ratings yet

- India Is The Mother of SciencesDocument1 pageIndia Is The Mother of SciencesSandeep SharmaNo ratings yet

- Prospectus Prospectus 2017-18 2017-18 Prospectus 2017-18Document115 pagesProspectus Prospectus 2017-18 2017-18 Prospectus 2017-18Sandeep SharmaNo ratings yet

- Abbreviations Used in TranslationDocument2 pagesAbbreviations Used in TranslationSandeep SharmaNo ratings yet

- On Indian TranslationDocument1 pageOn Indian TranslationSandeep SharmaNo ratings yet

- TextDocument43 pagesTextSandeep SharmaNo ratings yet

- DebatetopicsDocument1 pageDebatetopicsSandeep SharmaNo ratings yet

- Accent Training: - Neutralization - American - British 30 HrsDocument1 pageAccent Training: - Neutralization - American - British 30 HrsShah PatelNo ratings yet

- Handbook of Information MADocument55 pagesHandbook of Information MASandeep SharmaNo ratings yet

- Literary AgentsDocument1 pageLiterary AgentsSandeep SharmaNo ratings yet

- Premchand and Language: On Translation, Cultural Nationalism, and IronyDocument16 pagesPremchand and Language: On Translation, Cultural Nationalism, and IronySandeep SharmaNo ratings yet

- Certainly Uncertain DerridaDocument34 pagesCertainly Uncertain DerridaSandeep SharmaNo ratings yet

- The Life of Bulleh ShahDocument16 pagesThe Life of Bulleh ShahAHSAN SH3ikh100% (2)

- Celta SyllbusDocument20 pagesCelta SyllbusNivanismNo ratings yet

- Baba Bulleh ShahDocument8 pagesBaba Bulleh ShahSandeep SharmaNo ratings yet

- MorphologyDocument9 pagesMorphologySandeep SharmaNo ratings yet

- 100 Best Last Lines From NovelsDocument2 pages100 Best Last Lines From NovelsmailfrmajithNo ratings yet

- Coleridge's ImaginationDocument15 pagesColeridge's ImaginationSandeep Sharma0% (1)

- Revised Pattern of RUSA: BA in EnglishDocument1 pageRevised Pattern of RUSA: BA in EnglishSandeep SharmaNo ratings yet

- The Object of Study: PPT LECTUREDocument40 pagesThe Object of Study: PPT LECTURESandeep SharmaNo ratings yet

- Short Intro To ENGLISH LITeratureDocument9 pagesShort Intro To ENGLISH LITeratureSandeep SharmaNo ratings yet

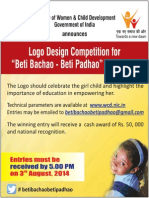

- Beti Bachao Beti Padhao Campaign 24072014Document5 pagesBeti Bachao Beti Padhao Campaign 24072014huzaifa17iNo ratings yet

- Rag Based SongsDocument16 pagesRag Based SongsSandeep SharmaNo ratings yet

- Communicating Certainty and Uncertainty in Language and BeyondDocument112 pagesCommunicating Certainty and Uncertainty in Language and BeyondSandeep SharmaNo ratings yet

- Periods Lit History PDFDocument2 pagesPeriods Lit History PDFHarry TapiaNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Assessment 2 Lesson Guide-RomeroDocument4 pagesAssessment 2 Lesson Guide-RomeroBabelyn RomeroNo ratings yet

- Child Development Milestones - 4 Year Old PDFDocument2 pagesChild Development Milestones - 4 Year Old PDFsevattapillaiNo ratings yet

- 1z0-148.exam.47q: Number: 1z0-148 Passing Score: 800 Time Limit: 120 MinDocument52 pages1z0-148.exam.47q: Number: 1z0-148 Passing Score: 800 Time Limit: 120 MinKuljasbir SinghNo ratings yet

- Google Project ProposalDocument4 pagesGoogle Project Proposalapi-301735741100% (1)

- English For Everyone Junior English DictionaryDocument136 pagesEnglish For Everyone Junior English DictionarySean Meehan100% (10)

- De Thi Thu Vao Lop 10 Mon Tieng Anh Nam 2020 2021 So 3Document5 pagesDe Thi Thu Vao Lop 10 Mon Tieng Anh Nam 2020 2021 So 3Jenny ĐoànNo ratings yet

- (All Aircraft Models) Mk-Xxii Egpws 060-4314-250 Installation ManualDocument324 pages(All Aircraft Models) Mk-Xxii Egpws 060-4314-250 Installation ManualPaulo Bernardo100% (1)

- Examples of Regular Verbs in SentencesDocument5 pagesExamples of Regular Verbs in SentencesANNIE WANNo ratings yet

- Mini-Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesMini-Lesson PlanTingyi Sun (Temmi)No ratings yet

- Deda HSG Tinh Mon Tieng Anh 9 Tinh Thanh Hoa Nam Hoc 20192020Document8 pagesDeda HSG Tinh Mon Tieng Anh 9 Tinh Thanh Hoa Nam Hoc 2019202036-9A-Nguyễn Trần QuangNo ratings yet

- A Math Summary BookletDocument113 pagesA Math Summary BookletbusinessNo ratings yet

- Integrated Speaking Task 2 - TemplateDocument3 pagesIntegrated Speaking Task 2 - Templatethata forgalianaNo ratings yet

- Philippine Arts from the RegionsDocument2 pagesPhilippine Arts from the RegionsBenilda Pensica SevillaNo ratings yet

- MS Excel Lab Exercises GuideDocument21 pagesMS Excel Lab Exercises GuideBindu Devender MahajanNo ratings yet

- Roland ErrorDocument2 pagesRoland ErrorBryanHumphriesNo ratings yet

- Business Configuration Sets (BC Sets) and Their Use - Basis Corner - SCN WikiDocument3 pagesBusiness Configuration Sets (BC Sets) and Their Use - Basis Corner - SCN WikimohannaiduramNo ratings yet

- Silent Speech Interface Using Facial Recognition and ElectromyographyDocument15 pagesSilent Speech Interface Using Facial Recognition and ElectromyographyM KISHORE,CSE(19-23) Vel Tech, Chennai100% (2)

- Introduction to Purposive CommunicationDocument57 pagesIntroduction to Purposive CommunicationNAld DaquipilNo ratings yet

- The Speaking Ability Taught by Using BrainstormingDocument12 pagesThe Speaking Ability Taught by Using BrainstormingGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Codigo Configuracion Tradingview v2Document3 pagesCodigo Configuracion Tradingview v2JulianMoraaNo ratings yet

- Ogh20180613 Rob LasonderDocument64 pagesOgh20180613 Rob LasonderViswa TejaNo ratings yet

- Ya Juj MajujDocument9 pagesYa Juj MajujmsobhanNo ratings yet

- Lab Manual - Exp - 4 - CMOS NAND NORDocument7 pagesLab Manual - Exp - 4 - CMOS NAND NORApoorvaNo ratings yet

- EEE 105 Lab ManualDocument27 pagesEEE 105 Lab ManualAdnan HossainNo ratings yet

- Rizal's Noli Me Tangere SummarizedDocument8 pagesRizal's Noli Me Tangere SummarizedNicole SuarezNo ratings yet

- Baby Shower Wish List by SlidesgoDocument52 pagesBaby Shower Wish List by Slidesgo20. Lê Thị Khánh LinhNo ratings yet

- Korean WikibooksDocument109 pagesKorean WikibooksFebiansyahHidayatNo ratings yet

- Motorik DelayDocument15 pagesMotorik DelaysindiNo ratings yet

- CV MustraDocument2 pagesCV MustraNot Available SorryNo ratings yet

- BCA DM Chapter 5 - ClusteringDocument42 pagesBCA DM Chapter 5 - ClusteringSelvarani ResearchNo ratings yet