Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Paper On Civil Indemnity

Uploaded by

JB DeangOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Paper On Civil Indemnity

Uploaded by

JB DeangCopyright:

Available Formats

PERSONAL INJURY AND OFFENDER’S CIVIL LIABILITY UNDER THE PHILIPPINE JURISDICTION

PERSONAL INJURY AND OFFENDER’S

CIVIL LIABILITY UNDER THE PHILIPPINE JURISDICTION

I. INTRODUCTION

In his book “The Revised Penal Code (Criminal Law Book One)”,

Retired Court of Appeals Associate Justice Luis B. Reyes stated that an

offense, as a general rule, causes two classes of injuries particularly social

injury and personal injury.1 Interestingly, to further comprehend the

underlying concepts of injuries caused by crimes, the ideas incorporated by

John Stuart Mill, the most influential and famous British philosopher of the

nineteenth century, in his renowned Harm Principle are hard to ignore.

According to Mill, in order to constitute harm, an action must be injurious or

set back important interests of particular people, interests in which they have

rights. Moreover, under this principle, Mill demonstrated claims which can be

used to satisfy explanations associated with the injuries or harms caused by

crimes. According to Mill, “[I]t must by no means be supposed, because

damage, to the interests of others, can alone justify the interference of society,

that therefore it always does justify such interference.” Moreover, he posited

that “[I]f anyone does an act hurtful to others, there is a prima facie case for

punishing him by law or, where legal penalties are safely applicable, by

general disapprobation.”2 Corollary, the interests of society and the offended

parties which have been wronged must be equally considered.3

Our laws recognize a bright line distinction between criminal and civil

liabilities. A crime is a liability against the state. It is prosecuted by and for

the state. Acts considered criminal are penalized by law as a means to protect

the society from dangerous transgressions. As criminal liability involves a

penalty affecting a person's liberty, acts are only treated criminal when the

law clearly says so. On the other hand, civil liabilities take a less public and

more private nature. Civil liabilities are claimed through civil actions as a

means to enforce or protect a right or prevent or redress a wrong.4

This is in line with the fact that in criminal prosecution, it is the State

that prosecutes crimes. The sovereign power has the inherent right to protect

itself and its people from vicious acts which endanger the proper

administration of justice; hence, the State has every right to prosecute and

punish violators of the law. This is essential for its self-preservation, nay, its

very existence.5 Indeed, the task of ridding society of criminals and misfits

and sending them to jail in the hope that they will in the future reform and be

productive members of the community rests both on the judiciousness of

1

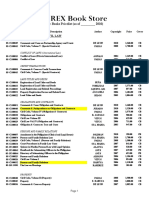

Reyes, Luis B. (2012). Title Five – Civil Liability (Chapter One – Persons Civilly Liable for Felonies). The

Revised Penal Code (Criminal Law Book One) (page 898). Quezon City, Philippines. REX Book Store.

2

Center for the Study of Language and Information, Stanford University (2007). Mill’s Moral and Political

Philosophy. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved from plato.stanford.edu.

3

The People of the Philippines vs. Hon. Judge Paterno V. Tac-an, G.R. No. 148000, February 27, 2003

4

Gloria S. Dy vs. People of the Philippines, G.R. No. 189081, August 10, 2016

5

Antonio Lejano vs. People of the Philippines, G.R. No. 176389, December 14, 2010

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE © 2017 1

PERSONAL INJURY AND OFFENDER’S CIVIL LIABILITY UNDER THE PHILIPPINE JURISDICTION

judges and the prudence of prosecutors.6 As significant as the right of the

accused to speedy trial is the right of the State to prosecute people who violate

its penal laws and who constitute a threat to the tranquility of the community.7

The use of the State of its entire machineries to prosecute crimes is evident of

it being the public offended party whenever an offense has been committed.

In this instance, the State suffers the so-called social injury. As defined by

former Associate Justice Reyes, social justice is produced by the disturbance

and alarm which are the outcome of the offense.8 Crimes are considered as

disturbance against peace and security of the people at large so it is the State

that has the right to prosecute. This is also emphasized by the requirement that

a complaint or information in criminal prosecution must be in the name of the

People of the Philippines under Section 2, Rule 110 of the Rules of Court.

Section 2. The complaint or information – The complaint or

information shall be in writing, in the name of the People of the

Philippines against all persons who appear to be responsible for

the offense involved.

The interest of the society to prevent social injury is attributed to the

reality that “each State has the authority, under its police power, to define and

punish crimes and to lay down the rules of criminal procedure. The states, as

a part of their police power, have a large measure of discretion in creating and

defining criminal offenses.”9 In accordance with State’s police power, it may

safely be affirmed, without further attempting to define what are the peculiar

subjects of limits of the police power, that every law for the restraint and

punishment of crimes, for the preservation of the public peace, health, and

morals, must come within this category.10 Such right was even reiterated by

the Supreme Court of the Philippines in U.S. vs. Pablo, to wit:

The right of prosecution and punishment for a crime is one of the

attributes that by a natural law belongs to the sovereign power

instinctively charged by the common will of the members of

society to look after, guard and defend the interests of the

community, the individual and social rights and the liberties of

every citizen and the guaranty of the exercise of his rights.

The power to punish evildoers has never been attacked or

challenged, as the necessity for its existence has been recognized

even by the most backward peoples. At times the criticism has

been made that certain penalties are cruel, barbarous, and

atrocious; at other, that they are light and inadequate to the nature

and gravity of the offense, but the imposition of punishment is

admitted to be just by the whole human race, and even barbarians

and savages themselves, who are ignorant of all civilization are

no exception.11

6

Diosdado Jose Allado vs. Hon. Roberto C. Diokno, G.R. No. 113630, May 5, 1994

7

People of the Philippines vs. Luis Tampal, G.R. No. 102485, May 22, 1995

8

Reyes, Luis B. Title Five – Civil Liability (Chapter One – Persons Civilly Liable for Felonies), 898

9

The People of the Philippine Islands vs. Gregorio Santiago, G.R. No. 17584, March 8, 1922

10

The People of the Philippine Islands vs. Julio Pomar, G.R. No. L-22008, November 3, 1924

11

The United States vs. Andres Pablo, G.R. No. L-11676, October 17, 1916

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE © 2017 2

PERSONAL INJURY AND OFFENDER’S CIVIL LIABILITY UNDER THE PHILIPPINE JURISDICTION

It is axiomatic that every person criminally liable for a felony is also

civilly liable.12 Criminal liability will give rise to civil liability only if the

felonious act or omission results in damage or injury to another and is the

direct and proximate cause thereof. Every crime gives rise to (1) a criminal

action for the punishment of the guilty party and (2) a civil action for the

restitution of the thing, repair of the damage, and indemnification for the

losses.13 Hence, a crime has dual character: (1) as an offense against the state

because of the disturbance of the social order; and (2) as an offense against

the private person injured by the crime unless it involves the crime of treason,

rebellion, espionage, contempt and others wherein no civil liability arises on

the part of the offender either because there are no damages to be compensated

or there is no private person injured by the crime. In the ultimate analysis,

what gives rise to the civil liability is really the obligation of everyone to repair

or to make whole the damage caused to another by reason of his act or

omission, whether done intentionally or negligently and whether or not

punishable by law.14

This refers now to the second class of injury caused by an offense, the

personal injury. Former Associate Justice Reyes defined personal injury as

the one caused to the victim of the crime who may have suffered damage,

either to his person, to his property, to his honor, or to her chastity. 15 Our

jurisdiction recognizes that a crime has a private civil component. Thus, while

an act considered criminal is a breach of law against the State, our legal system

allows for the recovery of civil damages where there is a private person

injured by a criminal act. It is in recognition of this dual nature of a criminal

act that our Revised Penal Code provides that every person criminally liable

is also civilly liable.16 Unlike social injury which is sought to be repaired

through the imposition of the corresponding penalty provided by law, personal

injury is through indemnity which is civil in nature.17 The rule is that every

act or omission punishable by law has its accompanying civil liability. The

civil aspect of every criminal case is based on the principle that every person

criminally liable is also civilly liable. If the accused however, is not found to

be criminally liable, it does not necessarily mean that he will not likewise be

held civilly liable because extinction of the penal action does not carry with it

the extinction of the civil action.18 This civil liability arising from culpa

criminal is found in Article 100 of the Revised Penal Code.

12

Dr. Encarnacion C. Lumantas, M.D. vs. Hanz Calapis, G.R. No. 163753, January 15, 2014

13

Sonny Romero y Dominguez vs. People of the Philippines, G.R. No. 167646, June 17, 2009

14

Occena vs. Icamina, G.R. No. 82146, January 22, 1990

15

Reyes, Luis B. Title Five – Civil Liability (Chapter One – Persons Civilly Liable for Felonies), 898

16

Gloria S. Dy vs. People of the Philippines, supra

17

Reyes, Luis B. Title Five – Civil Liability (Chapter One – Persons Civilly Liable for Felonies), 898

18

Nissan Gallery-Ortigas vs. Purificacion F. Felipe, November 11, 2013

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE © 2017 3

PERSONAL INJURY AND OFFENDER’S CIVIL LIABILITY UNDER THE PHILIPPINE JURISDICTION

Various codes of civil law incorporated or defined civil liability. For

example, Section 1383 of the French Civil Code of 1804 provides “[E]veryone

is liable for the damage he causes not only by his acts, but also by his

negligence or imprudence.” Also, Section 823 of the German Civil Code of

1900 founded civil liability on the following manner: “[A] person who,

willfully or negligently, unlawfully injures the life, body, health, freedom,

property or other right of another is bound to compensate him for any damage

arising therefrom.” It must be understood that the concept of civil liability or

delictual liability originates Roman law.19

In Philippine jurisdiction, civil liability, in general, is not only confined

to those arising from criminal offenses. Corollarily, an act or omission causing

damage to another may give rise to two separate civil liabilities on the part of

the offender, i.e., (1) civil liability ex delicto20, and (2) independent civil

liabilities, such as those (a) not arising from an act or omission complained of

as a felony (e.g., culpa contractual or obligation arising from law21; the

19

Civil Liability. Duhaime’s Law Dictionary

20

Article 100. Civil liability of a person guilty of felony. – Every person criminally liable for a felony is also

civilly liable. (Revised Penal Code of the Philippines)

21

Article 31. When the civil action is based on an obligation not arising from the act or omission complained

of as a felony, such civil action may proceed independently of the criminal proceedings and regardless of

the result of the latter. (Civil Code of the Philippines)

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE © 2017 4

PERSONAL INJURY AND OFFENDER’S CIVIL LIABILITY UNDER THE PHILIPPINE JURISDICTION

intentional torts22; culpa aquiliana23); or (b) where the injured party is granted

a right to file an action independent and distinct from the criminal action.24

Either of these two may be enforced against the offender.25 However, this is

subject to the caveat under Article 2177 of the Civil Code that the offended

party cannot recover damages twice for the same act or omission or under both

causes.26

22

Article 32. Any public officer or employee, or any private individual, who directly or indirectly obstructs,

defeats, violates or in any manner impedes or impairs any of the following rights and liberties of another

person shall be liable to the latter for damages:

1. Freedom of religion;

2. Freedom of speech;

3. Freedom to write for the press or to maintain a periodical publication;

4. Freedom from arbitrary or illegal detention;

5. Freedom of suffrage;

6. The right against deprivation of property without due process of law;

7. The right to a just compensation when private property is taken for public use;

8. The right to the equal protection of the laws;

9. The right to be secure in one’s person, house, papers, and effects against unreasonable searches

and seizures;

10. The liberty of abode and of changing the same;

11. The privacy of communication and correspondence;

12. The right to become a member of associations or societies for purposes not contrary to law;

13. The right to take part in a peaceable assembly to petition the Government for redress or

grievances;

14. The right to be free from involuntary servitude in any form;

15. The right of the accused against excessive bail;

16. The right of the accused to be heard by himself and counsel, to be informed of the nature and

cause of the accusation against him, to have a speedy and public trial, to meet the witnesses face

to face, and to have compulsory process to secure the attendance of witness in his behalf;

17. Freedom from being compelled to be a witness against one’s self, or from being forced to confess

guilt, or from being induced by a promise of immunity or reward to make such confession except

when the person confessing becomes a State witness;

18. Freedom from excessive fines, or cruel and unusual punishment, unless the same is imposed or

inflicted in accordance with a statute which has not been judicially declared unconstitutional; and

19. Freedom of access to the courts.

In any of the cases referred to in this article, whether or not the defendant’s act or omission constitutes

a criminal offense, the aggrieved party has a right to commence an entirely separate and distinct civil action

for damages, and for other relief. Such civil action shall proceed independently of any criminal prosecution

(if the latter be instituted), and may be proved by a preponderance of evidence.

The indemnity shall include moral damages. Exemplary damages may also be adjudicated.

The responsibility herein set forth is not demandable from a judge unless his act or omission constitutes

a violation of the Penal Code or other penal statute. (Civil Code of the Philippines)

Article 34. When a member of a city or municipal police force refuses or fails to render aid or protection

to any person in case of danger to life or property, such peace officer shall be primarily liable for damages,

and the city or municipality shall be subsidiarily responsible therefor. The civil action herein recognized shall

be independent of any criminal proceedings, and a preponderance of evidence shall suffice to support such

action. (Civil Code of the Philippines)

23

Article 2176. Whoever by act or omission causes damage to another, there being fault or negligence, is

obliged to pay for the damage done. Such fault or negligence, if there is no pre-existing contractual relation

between the parties, is called a quasi-delict and is governed by the provisions of this Chapter. (Civil Code of

the Philippines)

24

Article 33. In cases of defamation, fraud, and physical injuries, a civil action for damages, entirely separate

and distinct from the criminal action, may be brought by the injured party. Such civil action shall proceed

independently of the criminal prosecution, and shall require only a preponderance of evidence. (Civil Code

of the Philippines)

25

L.G. Foods Corporation vs. Hon. Philadelfa B. Pagapong-Agraviador, G.R. No. 158995, September 26, 2006

26

Safeguard Security Agency, Inc. vs. Lauro Tangco, G.R. No. 165732, December 14, 2006

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE © 2017 5

PERSONAL INJURY AND OFFENDER’S CIVIL LIABILITY UNDER THE PHILIPPINE JURISDICTION

Article 2177. Responsibility for fault or negligence under the

preceding article is entirely separate and distinct from the civil

liability arising from negligence under the Penal Code. But the

plaintiff cannot recover damages twice for the same act or

omission of the defendant.

The Revised Penal Code of the Philippines further provides that the

civil liability includes (1) restitution, (2) reparation of the damage caused, and

(3) indemnification for consequential damages.27

27

Lu Chu Sing vs. Lu Tiong Gui, G.R. No. L-122, May 11, 1946

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE © 2017 6

PERSONAL INJURY AND OFFENDER’S CIVIL LIABILITY UNDER THE PHILIPPINE JURISDICTION

PERSONAL INJURY AND OFFENDER’S

CIVIL LIABILITY UNDER THE PHILIPPINE JURISDICTION

II. CIVIL LIABILITY

An act or omission is felonious because it is punishable by law, it gives

rise to civil liability not so much because it is a crime but because it caused

damage to another. Additionally, what gives rise to the civil liability is really

the obligation and the moral duty of everyone to repair or make whole the

damage caused to another by reason of his own act or omission, whether done

intentionally or negligently. The indemnity which a person is sentenced to pay

forms an integral part of the penalty imposed by law for the commission of

the crime.28 It is, indeed, a basic tenet of our criminal law that every person

criminally liable is also civilly liable.29 The civil liability arising from the

crime may be determined in the criminal proceedings.30 To enforce the civil

liability, the Rules of Court has deemed to be instituted with the criminal

action the civil action for the recovery of civil liability arising from the offense

charged unless the offended party waives the civil action, or reserves the right

to institute the civil action separately, or institutes the civil action prior to the

criminal action.31 The civil liability arising from the crime may be determined

in the criminal proceedings if the offended party does not waive to have it

adjudged or does not reserve the right to institute a separate civil action against

the defendant. Furthermore, Article 104 of the Revised Penal Code

enumerates the matters covered by the civil liability arising from crimes, to

wit:

Article 104. What is included in civil liability. – The civil

liability established in Articles 100, 101, 102, and 103 of this

Code includes:

1. Restitution;

2. Reparation of the damage caused;

3. Indemnification for consequential damages.32

Restitution

Restitution has been defined in other criminal jurisdictions as payment

made by the perpetrator of the crime to the offended parties. 33 However, in

the Philippines, restitution is performed by returning the thing itself. The civil

liability of the offender to make restitution, under Art. 105 of the Revised

Penal Code, does not arise until his criminal liability is finally declared.34 The

purpose of the law is to place the offended party as much as possible in the

same condition as he was before the offense was committed against him. So

if the crime consist in the taking away of his property, the first remedy granted

28

Lee Pue Liong vs. Chua Pue Chin Lee, G.R. No. 181658, August 7, 2013

29

People of the Philippines vs. Ma. Harleta Velasco y Briones, G.R. No. 195668, June 25, 2014

30

Lee Pue Liong vs. Chua Pue Chin Lee, supra

31

People of the Philippines vs. Ma. Harleta Velasco y Briones, supra

32

Proton Pilipinas Corporation vs. Republic of the Philippines, G.R. No. 165027, October 12, 2006

33

Criminal.findlaw.com

34

Chua Hai vs. Hon. Ruperto Kapunan, G.R. No. L-11108, June 30, 1958

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE © 2017 7

PERSONAL INJURY AND OFFENDER’S CIVIL LIABILITY UNDER THE PHILIPPINE JURISDICTION

is that of restitution of the thing taken away. If restitution can not be made,

the law allows the offended party the next best thing, reparation.35 When the

crime is not against property, no restitution of the thing can be done. 36 In a

case, the Supreme Court, applying Article 105 37, obliged the appellant to

return the items he took from the spouses BBB and CCC. If appellant can no

longer return the articles taken, he is obliged to make reparation for their

value, taking into consideration their price and their special sentimental value

to the offended parties. Hence, the Court, modifying the decision of the trial

court, as affirmed by the CA, directed the appellant to return the pieces of

jewelry and valuables taken from the spouses BBB and CCC as enumerated

in the Information and proven during trial.38

Also, in the case of Visitacion A. Gacula vs. Pilar Martinez, the agent

as in this case was prosecuted for estafa, convicted, and sentenced to pay the

value of the jewelry or suffer subsidiary imprisonment in case of insolvency.

And yet, the Court held that the owner could recover said jewelry from the

pawnshop owner, citing in support of its holding the provisions of Article 120

of the old penal code, from which was copied article 105 of the Revised Penal

Code.39 This case has somehow similarities in a case decided before Visitacion

A. Gacula vs. Pilar Martinez where the court applied Article 120 of the old

penal code40. In the latter case, Arenas vs. Raymundo¸ several pieces of

jewelry were delivered by the owner to an agent to be sold on commission,

but the agent instead of selling the jewelry or accounting for their value,

pledged the same to a pawnshop.41 The Court in Arenas vs. Raymundo ruled

that the provisions contained in the first two paragraphs of Article 120 are

based on the uncontrovertible principle of justice that the party injured

through a crime has, as against all others, a preferential right to be

indemnified, or to have restored to him the thing of which he was unduly

deprived by criminal means.42 The same case provided a brief background of

Article 120 of the old penal code from which the present Article 105 was

derived in relation to possession of personal property.

35

The People of the Philippines vs. Antonio Espada, G.R. No. L-5684, January 22, 1954

36

De las Penas vs. Royal Bus Co., Inc., C.A., 56 O.G. 4052

37

Article 105. Restitution – How made. – The restitution of the thing itself must be made whenever

possible, with allowance for any deterioration, or diminution of value as determined by the court.

The thing itself shall be restored, even though it be found in the possession of a third person who

has acquired it by lawful means, saving to the latter his action against the proper person, who may be liable

to him.

This provision is not applicable in cases in which the thing has been acquired by the third person

in the manner and under the requirements which, by law, bar an action for its recovery.

38

People of the Philippines vs. Edgar Evangelio y Gallo, G.R. No. 181902, August 31, 2011

39

Visitacion A. Gacula vs. Pilar Martinez, G.R. No. L-3038, January 31, 1951.

40

Article 120. The restitution of the thing itself must be made, if be in the possession of a third person, who

had acquired it in a legal manner, reserving, however, his action against the proper person.

Restitution shall be made, even though the thing may be in the possession of a third person, who

had acquired it in a legal manner, reserving, however, his action against the proper person.

This provision is not applicable to a case in which the third person has acquired the thing in the

manner and with the requisites established by law to make it unrecoverable.

41

Visitacion A. Gacula vs. Pilar Martinez, supra

42

Estanislaua Arenas, et al. vs. Fausto O. Raymundo, G.R. No. L-5741

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE © 2017 8

PERSONAL INJURY AND OFFENDER’S CIVIL LIABILITY UNDER THE PHILIPPINE JURISDICTION

In view of the harmonious relation between the different codes in

force in these Islands, it is natural and logical that the

aforementioned provision of the Penal Code, based on the rule

established in article 17 of the same, to wit, that every person

criminally liable for a crime or misdemeanor is also civilly liable,

should be in agreement and accordance with the provisions of

article 464 of the Civil Code which prescribes:

The possession of personal property, acquired in good faith, is

equivalent to a title thereto. However, the person who has lost

personal property or has been illegally deprived thereof may

recover it from whoever possesses it.

If the possessor of personal property, lost or stolen, has acquired

it in good faith at a public sale, the owner can not recover it

without reimbursing the price paid therefor.

Neither can the owner of things pledged in pawnshops,

established with the authorization of the Government, recover

them, whosoever may be the person who pledged them, without

previously refunding to the institution the amount of the pledge

and the interest due.

With regard to things acquired on exchange, or at fairs or markets

or from a merchant legally established and usually employed in

similar dealings, the provisions of the Code of Commerce shall

be observed.43

The doctrines laid down in both two cases are compatible with the

decisions of the court in the old cases of Varela vs. Matute and Varela vs.

Finnick. In the former, Nicolasa Pascual received for sale on commission

several jewels owned by Josefa Varela upon condition that she would turn

over to the latter the proceeds thereof when sold, or to return them to her if

they could not be disposed of. Nicolasa Pascual, however, instead of

complying with the agreement, and acting fraudulently and in bad faith,

pledged the said jewels at the pawnshop of Antonio Matute, according to the

pawn ticket issued by him stating that for a certain consideration, which the

said Pascual had received from the pawnbroker, she delivered in pledge the

aforesaid jewelry. The Court, in view of the evidence adduced, ordered to

make restitution of the stolen jewels to Josefa Varela, or otherwise to pay the

value thereof, and, in case of insolvency, to suffer the corresponding

subsidiary imprisonment.44 In Varela vs. Finnick, it was found that not only

has the ownership and the origin of the jewels misappropriated been

unquestionably proven but also that the accused, acting fraudulently and in

bad faith, disposed of them and pledged them contrary to agreement, with no

right of ownership, and to the prejudice of the injured party, who was thereby

illegally deprived of said jewels; therefore, the owner has an absolute right to

recover the jewels from the possession of whosoever holds them. 45

43

Ibid.

44

Josefa Varela vs. Antonio Matute, G.R. No. L-3889, January 2, 1908

45

Josefa Varela vs. Josephine Finnick, G.R. No. L-3890, January 2, 1908

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE © 2017 9

PERSONAL INJURY AND OFFENDER’S CIVIL LIABILITY UNDER THE PHILIPPINE JURISDICTION

Varela vs. Finnick explained the relation of Article 17 of the old penal

code and a decision from the supreme court of Spain, to wit:46

Article 17 of the Penal Code provides that —

"Every person criminally liable for a crime or misdemeanor is

also civilly liable."

In accordance with this provision the supreme court [of Spain] in

its decision of the 3d of January, 1877, has established the

following doctrine:

"In order that civil liability may be decreed in a prosecution it is

necessary that it arise from or be the consequence of criminal

liability; therefore, if the accused was acquitted of a crime, any

court sentencing him by reason of the same to pay certain

indemnity does so in violation of this article."

The doctrine enunciated in Varela vs. Finnick was also applied in a case

decided six years after it. The Court, speaking through Justice Johnson, said

“[T]he record does not show whether or not the ring was returned to its owner,

in accordance with the provisions of article 120 of the Penal Code. It is a

general principle that no man can be divested of his property without his own

consent or voluntary act. In the case of Varela vs. Finnick (9 Phil. Rep., 482)

this court said, speaking through Mr. Justice Torres: ‘Whoever may have been

deprived of his property in consequence of a crime, is entitled to the recovery

thereof, even if such property is in the possession of a third party who acquired

it by legal means other than those expressly stated in article 464 of the Civil

Code.’” Article 464 of the Civil Code can now be found under Articles 559 47

and 1505 48 of the New Civil Code of the Philippines.49

46

Ibid.

47

Art. 559. The possession of movable property acquired in good faith is equivalent to a title. Nevertheless,

one who has lost any movable or has been unlawfully deprived thereof may recover it from the person in

possession of the same.

If the possessor of a movable lost or which the owner has been unlawfully deprived, has acquired

it in good faith at a public sale, the owner cannot obtain its return without reimbursing the price paid

therefor.

48

Article 1505. Subject to the provisions of this Title, where goods are sold by a person who is not the owner

thereof, and who does not sell them under authority or with the consent of the owner, the buyer acquires

no better title to the goods than the seller had, unless the owner of the goods is by his conduct precluded

from denying the seller's authority to sell.

Nothing in this Title, however, shall affect:

1. The provisions of any factors' act, recording laws, or any other provision of law enabling the

apparent owner of goods to dispose of them as if he were the true owner thereof;

2. The validity of any contract of sale under statutory power of sale or under the order of a court of

competent jurisdiction;

3. Purchases made in a merchant's store, or in fairs, or markets, in accordance with the Code of

Commerce and special laws.

49

The United States vs. Vicente F. Sotelo, G.R. No. L-9791, October 3, 1914

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE © 2017 10

PERSONAL INJURY AND OFFENDER’S CIVIL LIABILITY UNDER THE PHILIPPINE JURISDICTION

Nevertheless, under the Civil Code, a person illegally deprived of any

movable may recover it from the person in possession of the same and the

only defense the latter may have is if he has acquired it in good faith at a public

sale, in which case, the owner cannot obtain its return without reimbursing the

price paid therefor.50 This was also reiterated in the previous case of Cruz vs.

Pahati where plaintiff has been illegally deprived of his car through the

ingenious scheme of defendant B to enable the latter to dispose of it as if he

were the owner thereof. The Court said “[I]t appears that "one who has lost

any movable or has been unlawfully deprived thereof, may recover it from the

person in possession of the same" and the only defense the latter may have is

if he "has acquired it in good faith at a public sale" in which case "the owner

cannot obtain its return without reimbursing the price paid therefor." And

supplementing this provision, Article 1505 of the same Code provides that

"where goods are sold by a person who is not the owner thereof, and who does

not sell them under authority or with the consent of the owner, the buyer

acquires no better title to the goods than the seller had, unless the owner of

the goods is by his conduct precluded from denying the seller's authority to

sell.”51

Hence, Article 559 establishes two exceptions to the general rule of

irrevindicability, to wit, when the owner (1) has lost the thing, or (2) has been

unlawfully deprived thereof. In these cases, the possessor cannot retain the

thing as against the owner, who may recover it without paying any indemnity,

except when the possessor acquired it in a public sale.52 In a case, had the

defendant acquired the carabao in question in good faith at a public sale, he

would be entitled to reimbursement by the real owner upon recovery by the

latter; but he did not obtain the animal at a public sale, but by private purchase

from the other defendant. The registration of the purchase and transfer in the

books of a municipality does not confer a public character upon a sale agreed

to between two individuals only, without previous publication of notice for

general information in order that bidders may appear. He then should restore

the carabao to the real owner thereof.53

In People vs. Juan Alejano y De la Cruz, the appellant contends that

since the defendant has been acquitted, there was no reason for ordering the

return of the ring to its alleged owner, citing cases of the Supreme Court of

Spain, and that of Almeida Ghantangco and Lete vs. Abaroa (40 Phil., 1056).

However, the Court ruling in contrary of his contention said that it must not

be lost sight of that the defendant was not sentenced to pay any indemnity,

nor was anything adverse to him ordered. The defendant did not claim any

right to the ring, having ignored it entirely by denying that he had taken it and

pawned it in the pawnshop mentioned. The return of the ring to its owner,

Pedro Razal, did not injure the defendant or anybody else, except the

50

Jose B. Aznar vs. Rafael Yapdiangco, G.R. No. L-18536, March 31, 1965

51

Jose R. Cruz vs. Reynaldo Pahati et al., G.R. No. L-8257, April 13, 1956

52

Jose B. Aznar vs. Rafael Yapdiangco, supra

53

The United States vs. Garino Soriano, G.R. No. 4563, January 19, 1909

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE © 2017 11

PERSONAL INJURY AND OFFENDER’S CIVIL LIABILITY UNDER THE PHILIPPINE JURISDICTION

appellant, who, however, until shown to be one of the "pawnshops established

under authority of the Government" mentioned in the third paragraph of article

464, Civil Code, has no right to reimbursement of the amount for which the

ring in question was pledged.54

Reparation

If the crime consists in the taking away of his property, the first remedy

granted is that of restitution of the thing taken away. If restitution can not be

made, the law allows the offended party the next best thing, reparation.55 In

People vs. Mostasesa¸ the Court cited Spanish jurist Viada who, commenting

on the provision of the Revised Penal Code on reparation, said:56

En las causas por robo, hurto, etc. en que no hayan sido recuperados

durante el proceso los objetos de dichos delitos, debe condenarse a

los reos a su restitucion, o, en su defecto, a la indemnizacion

correspondiente en el cantidad en que hayan sido valorados o

tasados por los peritos; . . . . (3 Viada 6)

Under international law, reparation is a principle of law which refers

to the obligation of the offender to redress the damasge caused to the offended

party. Moreover, "reparation must, as far as possible, wipe out all the

consequences of the illegal act and re-establish the situation which would, in

all probability, have existed if that act had not been committed."57

Reparation may not be made by the delivery of a similar thing (same

amount, kind or species and quality), because the value of the thing taken may

have decreased since the offended party was deprived thereof. Reparation,

therefore, should consist of the price of the thing taken, as fixed by the court

(article 106, Revised Penal Code).58

Article 106. Reparation – How made. – The court shall determine

the amount of damage, taking into consideration the price of the

thing, whenever possible, and its special sentimental value to the

injured party, and reparation shall be made accordingly.

In a case, the Court had the occasion to apply Article 106. Thus, the

value of the stolen ring is another question raised by the appellant, who

contends that it was worth only P200. To the price of P1,200 at which the

appellant claimed to have sold the ring, the Court of Appeals added P800 to

cover its sentimental value to the owner, considering that it was a souvenir

from her mother, thus raising the value to P2,000. Article 106 of the Revised

Penal Code provides that "the court shall determine the amount of damage,

taking into consideration the price of the thing, whenever possible, and its

54

People vs. Juan Alejano y De la Cruz, G.R. No. 33667, October 4, 1930

55

The People of the Philippines vs. Pelagio Mostasesa, G.R. No. L-5684, January 22, 1954

56

Ibid.

57

Redress. What is reparation?. Retrieved from http://www.redress.org

58

The People of the Philippines vs. Pelagio Mostasesa, supra

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE © 2017 12

PERSONAL INJURY AND OFFENDER’S CIVIL LIABILITY UNDER THE PHILIPPINE JURISDICTION

special sentimental value to the injured party, and reparation shall be made

accordingly." Appellant’s contention that the ring should be appraised at only

P200 is manifestly untenable, he himself having paid P800 for it and having

sold it later for P1,200. In any event, the question raised is one of fact as to

which the finding of the Court of Appeals is final.59 However, if there is no

evidence as to the value of the thing unrecovered, reparation cannot be made

(People vs. Dalena, C.A., G.R. Nos. 11387-R and 11388-R, October 25,

1954).60

In the computation of civil liability, the Court in U.S. vs. Yambao, added

the indemnification of 3 reales and 12 cuartos, the value of the mutilated

garment, which the judge imposed on the defendant, as reparation merely for

the damage caused by this offense against her property, but for the offense

against chastity he should respond for a damage of a different and a higher

entity, and this reparation should always be a civil reparation corresponding

to the character of the crime which injures both honor and chastity. 61

Indemnification

Likewise, reparation and indemnification are similarly defined as the

compensation for an injury, wrong, loss, or damage sustained.62 Thus,

according to law and jurisprudence, civil indemnity is in the nature of actual

and compensatory damages for the injury caused to the offended party and

that suffered by her family, and moral damages are likewise compensatory in

nature. The fact of minority of the offender at the time of the commission of

the offense has no bearing on the gravity and extent of injury caused to the

victim and her family, particularly considering the circumstances attending

this case.63 Moreover, in People vs. Sarcia, the Court reiterated that it

explained in People v. Gementiza64 that the indemnity authorized by our

criminal law as civil liability ex delicto for the offended party, in the amount

authorized by the prevailing judicial policy and aside from other proven actual

damages, is itself equivalent to actual or compensatory damages in civil law.65

Article 107 66 of the Revised Penal Code provides that the

indemnification for damages includes not only those caused the injured party

but also those suffered by his family or by a third person. This finds

application in the case of Alfredo Copacio, et al. vs. Luzon Brokerage Co.,

Inc., wherein the Court sustained the lower court in the following manner:

59

Jose Cristobal vs. The People of the Philippines, G.R. No. L-1542, August 30, 1949

60

Reyes, Luis B. Title Five – Civil Liability (Chapter One – Persons Civilly Liable for Felonies), 942

61

The United States vs. Jose Yambao, G.R. No. 1662, February 13, 1905

62

People of the Philippines vs. Jose Pepito D. Combate, G.R. No. 189301, December 15, 2010

63

People of the Philippines vs. Richard O. Sarcia, G.R. No. 169641, September 10, 2009

64

People of the Philippines vs. Sabino Gementiza, G.R. No. 123151, January 29, 1998

65

People of the Philippines vs. Richard O. Sarcia, supra

66

Article 107. Indemnification; What is included. - Indemnification for consequential damages shall include

not only those caused the injured party, but also those suffered by his family or by a third person by reason

of the crime.

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE © 2017 13

PERSONAL INJURY AND OFFENDER’S CIVIL LIABILITY UNDER THE PHILIPPINE JURISDICTION

The appealed judgment sentenced the defendant-appellant to pay

P500 for the death of each of the victims, or a total of P2,000, plus

legal interest. In its second assignment of error the defendant

contends that, at the most, it should have been sentenced to pay the

total sum of P1,500, at the rate of P500 for each family of the

deceased. The argument is based upon the language of the

judgment rendered in the criminal case wherein the court sentenced

the accused to pay, by way of indemnity, P500 to each family of

victims. It is true that there are only three families, because the

deceased Delfin Copiaco and Fidel Copiaco are both children of

the spouses Alfredo Copiaco and Nieves Alarcon. However, we do

not believe that the court committed the error assigned. Article 107

of the Revised Penal Code provides that the indemnization for

damages includes not only those caused the injured party but also

those suffered by his family or by a third person. In the present case

it is undoubted that the family or the heirs of the deceased Delfin

Copiaco and Fidel Copiaco have suffered double damage by reason

of the death of their two children, with the consequence that it is

just to indemnity them in the same measure for the death of each

of the two members of the family.67

Contributory negligence on the part of the offended party nevertheless

reduces the civil liability of the offender. Thus, in a case where Sonny Soriano,

the victim, while crossing Commonwealth Avenue near Luzon Avenue in

Quezon City, was hit by a speeding Tamaraw FX driven by Lomer Macasasa.

Soriano was thrown five meters away, the Court agreed that the Court of

Appeals did not err in ruling that Soriano was guilty of contributory

negligence for not using the pedestrian overpass while crossing

Commonwealth Avenue. The Court even noted that the respondents admit this

point, and concede that the appellate court had properly reduced by 20% the

amount of damages it awarded. The reduction of the amount earlier awarded

was based on Article 2179 of the Civil Code.68

Article 2179. When the plaintiff's own negligence was the

immediate and proximate cause of his injury, he cannot recover

damages. But if his negligence was only contributory, the

immediate and proximate cause of the injury being the defendant's

lack of due care, the plaintiff may recover damages, but the courts

shall mitigate the damages to be awarded.

In Lambert vs. Heirs of Castillon, the Court said that the underlying

precept on contributory negligence is that a plaintiff who is partly responsible

for his own injury should not be entitled to recover damages in full but must

bear the consequences of his own negligence. The defendant must thus be held

liable only for the damages actually caused by his negligence. The

determination of the mitigation of the defendants liability varies depending on

the circumstances of each case. Conclusively, when in a vehicle accident, it

was established that the victim, at the time of the mishap: (1) was driving the

motorcycle at a high speed; (2) was tailgating the Tamaraw jeepney; (3) has

67

Alfredo Copacio, et al. vs. Luzon Brokerage Co., G.R. No. 46135, September 19, 1938

68

Flordeliza Mendoza vs. Mutya Soriano, G.R. No. 164012, June 8, 2007

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE © 2017 14

PERSONAL INJURY AND OFFENDER’S CIVIL LIABILITY UNDER THE PHILIPPINE JURISDICTION

imbibed one or two bottles of beer; and (4) was not wearing a protective

helmet, these circumstances, although not constituting the proximate cause of

his demise and injury to Sergio, contributed to the same result. The

contribution of these circumstances are all considered and determined in terms

of percentages of the total cause. Hence, the heirs of Ray Castillon shall

recover damages only up to 50% of the award. In other words, 50% of the

damage shall be borne by the private respondents; the remaining 50% shall be

paid by the petitioner.69

Civil indemnity may also be increased. In a case, the Court ordered the

appellant to indemnify the heirs of the victim since death resulted from the

crime. The heirs of the victim are entitled to an award of civil indemnity in

the amount of ₱75,000.00, which is mandatory and is granted without need of

evidence other than the commission of the crime. Hence, the Court increased

the award for civil indemnity made by the trial court and affirmed by the CA

from ₱50,000.00 to ₱75,000.00. Also, while the CA correctly ordered

appellant to pay the heirs of the victim exemplary damages, the amount

awarded must be increased from ₱25,000.00 to ₱30,000.00 in line with current

jurisprudence.70 However, the civil indemnity may be increased only if it will

not require an aggravation of the decision in the criminal case on which it is

based. In other words, the accused may not, on appeal by the adverse party,

be convicted of a more serious offense or sentenced to a higher penalty to

justify the increase in the civil indemnity.71

Exemption from Criminal Liability and Its Effects on Civil Liability

Every person criminally liable is also civilly liable. However, it does

not follow that a person who is not criminally liable is also free from civil

liability. Exemption from criminal liability does not always include

exemption from civil liability.72 An exempting circumstance, by its nature,

admits that criminal and civil liabilities exist, but the accused is freed from

criminal liability; in other words, the accused committed a crime, but he

cannot be held criminally liable therefor because of an exemption granted by

law.73 The rules regarding civil liability in certain cases are governed by

Article 101 of the Revised Penal Code of the Philippines.

Article 101. Rules regarding civil liability in certain cases. - The

exemption from criminal liability established in subdivisions 1, 2,

3, 5 and 6 of Article 12 and in subdivision 4 of Article 11 of this

Code does not include exemption from civil liability, which shall

be enforced subject to the following rules:

First. In cases of subdivisions 1, 2, and 3 of Article 12, the civil

liability for acts committed by an imbecile or insane person, and by

a person under nine years of age, or by one over nine but under

69

Nelen Lambert vs. Heirs of Ray Castillon, G.R. No. 160709, February 23, 2005

70

People of the Philippines vs. Joemari Jalbonian, G.R. No. 180281, July 1, 2013

71

Heirs of Tito Rillorta vs. Hon. Romeo N. Firme, G.R. No. L-54904, January 29, 1988

72

The People of the Philippines vs. Hon. Judge Catalino Castaneda Jr., G.R. No. L-49781-91, June 24, 1983

73

Robert Sierra y Caneda vs. People of the Philippines, G.R. No. 182941, July 3, 2009

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE © 2017 15

PERSONAL INJURY AND OFFENDER’S CIVIL LIABILITY UNDER THE PHILIPPINE JURISDICTION

fifteen years of age, who has acted without discernment, shall

devolve upon those having such person under their legal authority

or control, unless it appears that there was no fault or negligence

on their part.

Should there be no person having such insane, imbecile or minor

under his authority, legal guardianship or control, or if such person

be insolvent, said insane, imbecile, or minor shall respond with

their own property, excepting property exempt from execution, in

accordance with the civil law.

Second. In cases falling within subdivision 4 of Article 11, the

persons for whose benefit the harm has been prevented shall be

civilly liable in proportion to the benefit which they may have

received.

The courts shall determine, in sound discretion, the proportionate

amount for which each one shall be liable.

When the respective shares cannot be equitably determined, even

approximately, or when the liability also attaches to the

Government, or to the majority of the inhabitants of the town, and,

in all events, whenever the damages have been caused with the

consent of the authorities or their agents, indemnification shall be

made in the manner prescribed by special laws or regulations.

Third. In cases falling within subdivisions 5 and 6 of Article 12,

the persons using violence or causing the fears shall be primarily

liable and secondarily, or, if there be no such persons, those doing

the act shall be liable, saving always to the latter that part of their

property exempt from execution.

In a case, Anita Tan is the owner of a house of strong materials. The

Standard Vacuum Oil Company ordered the delivery to the Rural Transit

Company at its garage of 1,925 gallons of gasoline using a gasoline tank-truck

trailer. The truck was driven by Julito Sto. Domingo, who was helped by

Igmidio Rico. While the gasoline was being discharged to the underground

tank, it caught fire, whereupon Julito Sto. Domingo drove the truck across the

Rizal Avenue Extension and upon reaching the middle of the street, he

abandoned the truck which continued moving to the opposite side of the street

causing the buildings on that side to be burned and destroyed. The house of

Anita Tan was among those destroyed and for its repair she spent P12,000. As

an aftermath of the fire, Julito Sto. Domingo and Igmidio Rico were charged

with arson through reckless imprudence. The case of the Rural Transit Co.

here is predicated on a special provision of the Revised Penal Code

particularly Article 101, Rule 2. The Court explained its decision in the

following manner: “[C]onsidering the above quoted law and facts, the cause

of action against the Rural Transit Company can hardly be disputed, it

appearing that the damage caused to the plaintiff was brought about mainly

because of the desire of driver Julito Sto. Domingo to avoid greater evil or

harm, which would have been the case had he not brought the tank-truck

trailer to the middle of the street, for then the fire would have caused the

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE © 2017 16

PERSONAL INJURY AND OFFENDER’S CIVIL LIABILITY UNDER THE PHILIPPINE JURISDICTION

explosion of the gasoline deposit of the company which would have resulted

in a conflagration of much greater proportion and consequences to the houses

nearby or surrounding it. It cannot be denied that this company is one of those

for whose benefit a greater harm has been prevented, and as such it comes

within the purview of said penal provision.”74

Civil Liability in case of Imbecility and Insanity

Article 12 of the Revised Penal Code75 exempts from criminal liability

an imbecile or an insane person unless the latter has acted during a lucid

interval. Imbecile is a person marked by mental deficiency while an insane

person is one who has an unsound mind or suffers from a mental disorder (1

Viada, Codigo Penal, 4th Ed., p. 92.).76 The Court adopted the criterion for

insanity and imbecility in the case of People vs. Formigonez. In order that a

person could be regarded as an imbecile within the meaning of article 12 of

the Revised Penal Code so as to be exempt from criminal liability, according

to the Court, he must be deprived completely of reason or discernment and

freedom of the will at the time of committing the crime. The provisions of

article 12 of the Revised Penal Code are copied from and based on paragraph

1, article 8, of the old Penal Code of Spain. Consequently, the decisions of the

Supreme Court of Spain interpreting and applying said provisions are

pertinent and applicable. The Court cited Judge Guillermo Guevara on his

Commentaries on the Revised Penal Code, to wit:77

"The Supreme Court of Spain held that in order that this exempting

circumstance may be taken into account, it is necessary that there

be a complete deprivation of intelligence in committing the act, that

is, that the accused be deprived of reason; that there be no

responsibility for his own acts; that he acts without the least

discernment; 46 that there be a complete absence of the power to

74

Anita Tan vs. Standard Vacuum Oil Co., G.R. No. L-4160, July 29, 1952

75

Art. 12. Circumstances which exempt from criminal liability. — the following are exempt from criminal

liability:

1. An imbecile or an insane person, unless the latter has acted during a lucid interval.

When the imbecile or an insane person has committed an act which the law defines as a felony (delito),

the court shall order his confinement in one of the hospitals or asylums established for persons thus

afflicted, which he shall not be permitted to leave without first obtaining the permission of the same court.

2. A person under nine years of age.

3. A person over nine years of age and under fifteen, unless he has acted with discernment, in which

case, such minor shall be proceeded against in accordance with the provisions of Art. 80 of this

Code.

When such minor is adjudged to be criminally irresponsible, the court, in conformably with the

provisions of this and the preceding paragraph, shall commit him to the care and custody of his family

who shall be charged with his surveillance and education otherwise, he shall be committed to the care

of some institution or person mentioned in said Art. 80.

4. Any person who, while performing a lawful act with due care, causes an injury by mere accident

without fault or intention of causing it.

5. Any person who act under the compulsion of irresistible force.

6. Any person who acts under the impulse of an uncontrollable fear of an equal or greater injury.

7. Any person who fails to perform an act required by law, when prevented by some lawful

insuperable cause.

76

The People of the Philippines vs. Honorato Ambal, G.R. No. L-52688, October 17, 1980

77

The People of the Philippines vs. Abelardo Formigonez, G.R. No. L-3246, November 29, 1950

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE © 2017 17

PERSONAL INJURY AND OFFENDER’S CIVIL LIABILITY UNDER THE PHILIPPINE JURISDICTION

discern, or that there be a total deprivation of freedom of the will.

For this reason, it was held that the imbecility or insanity at the time

of the commission of the act should absolutely deprive a person of

intelligence or freedom of will, because mere abnormality of his

mental faculties does not exclude imputability.

"The Supreme Court of Spain likewise held that deaf-muteness

cannot be equalled to imbecility or insanity.

"The allegation of insanity or imbecility must be clearly proved.

Without positive evidence that the defendant had previously lost

his reason or was demented, a few moments prior to or during the

perpetration of the crime, it will be presumed that he was in a

normal condition. Acts penalized by law are always reputed to be

voluntary, and it is improper to conclude that a person acted

unconsciously, in order to relieve him from liability, on the basis

of his mental. condition, unless his insanity and absence of will are

proved."

As to the strange behaviour of the accused during his confinement,

assuming that it was not feigned to stimulate insanity, it may be

attributed either to his being feebleminded or eccentric, or to a

morbid mental condition produced by remorse at having killed his

wife. From the case of United States v. Vaquilar (27 Phil. 88), we

quote the following syllabus:

"Testimony of eye-witnesses to a parricide, which goes no further

than to indicate that the accused was moved by a wayward or

hysterical burst of anger or passion, and other testimony to the

effect that, while in confinement awaiting trial, defendant acted

absentmindedly at times, is not sufficient to establish the defense

of insanity. The conduct of the defendant while in confinement

appears to have been due to a morbid mental condition produced

by remorse."

When insanity of the defendant is alleged as a ground of defense or

reason for his exemption from responsibility, the evidence on this point must

refer to the time preceding to act under prosecution or at the very moment of

its execution. In such case, it is incumbent upon defendant’s counsel to prove

that his client was not in his right mind or that he acted under the influence of

a sudden attack of insanity or that he was generally regarded as insane when

he executed the act attributed to him. In order to ascertain a person’s mental

condition at the time of the act, it is permissible to receive evidence of his

mental condition during a reasonable period before and after. Direct testimony

is not required nor are specific acts of disagreement essential to establish

insanity as a defense. A person’s mind can only be plumbed or fathomed by

external acts. Thereby his thoughts, motives and emotions may be evaluated

to determine whether his external acts conform to those of people of sound

mind. To prove insanity, clear and convincing circumstantial evidence would

suffice. In a case, the Court was convinced that the testimonial and

documentary evidence marshalled in the case by acknowledged medical

experts have sufficiently established the fact that appellant was legally insane

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE © 2017 18

PERSONAL INJURY AND OFFENDER’S CIVIL LIABILITY UNDER THE PHILIPPINE JURISDICTION

at the time he committed the crimes. His previous confinements, as early as

1972, his erratic behaviour before the assaults and the doctor’s testimony that

he was having a relapse all point to a man deprived of complete freedom of

will or a lack of reason and discernment that should thus exempt him from

criminal liability. However, he was still made civilly liable under Article 101

of the Revised Penal Code.78

Civil Liability in case of Minority

Another exemption was also explained in a case pursuant to the

applicable provisions of Republic Act No. 9344 otherwise known as the

Juvenile Justice and Welfare Act of 2006. In this case, 19 year old AAA, a

household help of the spouses Constantino and Elvira Cueva, while on her

way to her parents' house, met appellants Vergel and Allain who wanted to go

with her but she refused. They suddenly held her hands but she was able to

get free from their hold. She then decided to return to her employers' house

but when she thought about her parents' need for the money, she just stayed

and waited at the side of the road hoping that the appellants would go away.

Thinking that appellants had already left, she continued walking to her

parents' house but appellants reappeared and held her hands again. She

shouted for help and struggled to be freed from their hold but appellant Allain

covered her mouth with a handkerchief and appellant Vergel punched her in

the stomach which caused her to lose consciousness. When AAA regained her

consciousness, she noticed that she was only wearing her t-shirt as her bra,

panty and maong pants were on her side. She felt pain all over her body. Her

vagina hurt and it was covered with blood. She went back to her employers'

house and told them that she was raped by appellants. Dr. Mary Ann Jabat of

the Severo Verallo Memorial District Hospital conducted an examination on

AAA finding in the perineum and hymen, her labia majora had erythema and

slight edema; and the vaginal swab indicated the presence of spermatozoa.

She said that the lacerations in the perineum and the hymen were due to the

insertion of a foreign object or the male organ and that the presence of

spermatozoa signifies recent sexual intercourse.79

The Court held that RA No. 9344 should be considered in determining

the imposable penalty on the appellant even if the crime was committed seven

years earlier. Appellant Allain was only 17 years old when he committed the

crime. Hence, the following provisions of R.A. No. 9344 were given due

consideration:80

[Sec. 68 of Republic Act No. 9344] allows the retroactive

application of the Act to those who have been convicted and are

serving sentence at the time of the effectivity of this said Act, and

who were below the age of 18 years at the time of the commission

78

The People of the Philippines vs. Roger Austria y Navarro, G.R. No. 111517-19, July 31, 1996

79

People of the Philippines vs. Vergel Ancajas, G.R. No. 199270, October 21, 2015

80

Ibid.

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE © 2017 19

PERSONAL INJURY AND OFFENDER’S CIVIL LIABILITY UNDER THE PHILIPPINE JURISDICTION

of the offense. With more reason, the Act should apply to this case

wherein the conviction by the lower court is still under review.

SEC. 6. Minimum Age of Criminal Responsibility. - A child

fifteen (15) years of age or under at the time of the commission of

the offense shall be exempt from criminal liability. However, the

child shall be subjected to an intervention program pursuant to

Section 20 of this Act.

A child above fifteen (15) yours but below eighteen (18) years of

age shall likewise be exempt from criminal liability and be

subjected to an intervention program, unless he/she has acted with

discernment, in which case, such child shall be subjected to the

appropriate proceedings in accordance with this Act.

The exemption from criminal liability herein established does not

include exemption from civil liability, which shall be enforced in

accordance with existing laws.

Thus, a determination of guilt is likewise relevant under the terms of

R.A. No. 9344 since its exempting effect is only on the criminal, not on the

civil liability. In tackling the issues of age and minority, we stress at the outset

that the ages of both the petitioner and the complaining victim are material

and are at issue. The age of the petitioner is critical for purposes of his

entitlement to exemption from criminal liability under R.A. No. 9344, while

the age of the latter is material in characterizing the crime committed and in

considering the resulting civil liability that R.A. No. 9344 does not remove.81

The intent of the State to promote and protect the rights of child in

conflict with the law is enshrined in R.A. No. 9344.82 The current law also

drew its changes from the principle of restorative justice83 that it espouses; it

considers the ages 9 to 15 years as formative years and gives minors of these

ages a chance to right their wrong through diversion and intervention

measures. This is the reason why this law modifies the minimum age limit of

criminal irresponsibility as well for minor offenders; it changed what

paragraphs 2 and 3 of Article 12 of the Revised Penal Code (RPC), as

amended, previously provided i.e., from under nine years of age and above

81

Robert Sierra y Caneda vs. People of the Philippines, G.R. No. 182941, July 3, 2009, supra

82

Section 2(d) of R.A. No. 9344 provides “[P]ursuant to Article 40 of the United Nations Convention on the

Rights of the Child, the State recognizes the right of every child alleged as, accused of, adjudged, or

recognized as having infringed the penal law to be treated in a manner consistent with the promotion of

the child's sense of dignity and worth, taking into account the child's age and desirability of promoting

his/her reintegration. Whenever appropriate and desirable, the State shall adopt measures for dealing with

such children without resorting to judicial proceedings, providing that human rights and legal safeguards

are fully respected. It shall ensure that children are dealt with in a manner appropriate to their well-being

by providing for, among others, a variety of disposition measures such as care, guidance and supervision

orders, counseling, probation, foster care, education and vocational training programs and other

alternatives to institutional care”

83

Section 4(q) of R.A. No. 9344 provides “"[R]estorative Justice" refers to a principle which requires a

process of resolving conflicts with the maximum involvement of the victim, the offender and the

community. It seeks to obtain reparation for the victim; reconciliation of the offender, the offended and

the community; and reassurance to the offender that he/she can be reintegrated into society. It also

enhances public safety by activating the offender, the victim and the community in prevention strategies.”

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE © 2017 20

PERSONAL INJURY AND OFFENDER’S CIVIL LIABILITY UNDER THE PHILIPPINE JURISDICTION

nine years of age and under fifteen (who acted without discernment) to fifteen

years old or under and above fifteen but below 18 (who acted without

discernment) in determining exemption from criminal liability. In providing

exemption, the new law as the old paragraphs 2 and 3, Article 12 of the RPC

did presume that the minor offenders completely lack the intelligence to

distinguish right from wrong, so that their acts are deemed involuntary ones

for which they cannot be held accountable.84

It is worthy to note the basic reason behind the enactment of the

exempting circumstances embodied in Article 12 of the RPS; the complete

absence of intelligence, freedom of action, or intent, or on the absence of

negligence on the part of the accused. In expounding on intelligence as the

second element of dolus, Albert has stated that “[T]he second element of dolus

is intelligence; without this power, necessary to determine the morality of

human acts to distinguish a licit from an illicit act, no crime can exist, and

because … the infant (has) no intelligence, the law exempts (him) from

criminal liability.” It is for this reason, therefore, why minors nine years of

age and below are not capable of performing criminal act.85 For one who acts

by virtue of any of the exempting circumstances, although he commits a

crime, by complete absence of any of the conditions which constitute free will

or voluntariness of the act, no criminal liability arises.86

In Sierra v. People, the Court explained minority as an exempting

circumstance. To wit:

R.A. No. 9344 was enacted into law on April 28, 2006 and took

effect on May 20, 2006. Its intent is to promote and protect the

rights of a child in conflict with the law or a child at risk by

providing a system that would ensure that children are dealt with

in a manner appropriate to their well-being through a variety of

disposition measures such a scare, guidance and supervision

orders, counseling, probation, foster care, education and

vocational training programs and other alternatives to

institutional care. More importantly in the context of this case, this

law modifies as well the minimum age limit of criminal

irresponsibility for minor offenders; it changed what paragraphs 2

and 3 of Article 12 of the Revised Penal Code (RPC), as amended,

previously provided i.e., from under nine years of age and above

nine years of age and under fifteen (who acted without

discernment) to fifteen years old or under and above fifteen years

but below 18 (who acted without discernment) in determining

exemption from criminal liability. In providing exemption, the new

law as the old paragraphs 2 and 3, Article 12 of the RPC did

presume that the minor offenders completely lack the intelligence

to distinguish right from wrong, so that their acts are deemed

involuntary ones for which they cannot be held accountable. The

current law also drew its changes from the principle of restorative

84

Robert Sierra y Caneda vs. People of the Philippines, G.R. No. 182941, July 3, 2009, supra

85

John Philip Guevarra v. Honorable Ignacio Almodovar, G.R. No. 75256, January 26, 1989

86

Joemar Ortega v. People of the Philippines, G.R. No. 151085, August 20 2008

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE © 2017 21

PERSONAL INJURY AND OFFENDER’S CIVIL LIABILITY UNDER THE PHILIPPINE JURISDICTION

justice that it espouses; it considers the ages 9 to 15 years as

formative years and gives minors of these ages a chance to right

their wrong through diversion and intervention measures.87

The last paragraph of Section 6 of R.A. No. 9344 provides that the

accused shall continue to be civilly liable despite his exemption from criminal

liability. The extent of civil liability depends on the crime that could have been

committed had the accused not been found to be exempt from criminal

liability.88 However, this must also yield to the question of whether or not the

accused has acted with or without discernment in order to determine criminal

liability and the appropriate civil liability. In modifying the criminal liability

of an accused, the Court had the occasion to apply such law in the case of

People of the Philippines v. Gambao89 where pursuant to the passing of R.A.

No. 9344, a determination of whether she [the accused] acted with or without

discernment is necessary. Discernment has been defined as the mental

capacity of a minor to fully appreciate the consequences of his unlawful act

and such capacity may be known and should be determined by taking into

consideration all the facts and circumstances afforded by the records in each

case.90 In this case, Perpenian, the accused, acted with discernment when she

was 17 years old at the time of the commission of the offense. Her minority

should be appreciated not as an exempting circumstance, but as a privileged

mitigating circumstance pursuant to Article 68 of the Revised Penal Code91.

Subsidiary Liability

In Calang vs. People of the Philippines, the prosecution charged Calang

with multiple homicide, multiple serious physical injuries and damage to

property thru reckless imprudence before the RTC. The RTC found Calang

guilty beyond reasonable doubt of reckless imprudence resulting to multiple

homicide, multiple physical injuries and damage to property. The RTC

ordered Calang and Philtranco, jointly and severally, to pay P50,000.00 as

death indemnity to the heirs of Armando, the victim; P50,000.00 as death

indemnity to the heirs of Mabansag, another victim; and P90,083.93 as actual

damages to the private complainants. The petitioners claim that there was no

basis to hold Philtranco, employer, jointly and severally liable with Calang

because the former was not a party in the criminal case (for multiple homicide

with multiple serious physical injuries and damage to property thru reckless

imprudence) before the RTC. The Court, holding that the RTC and CA both

87

Robert Sierra y Caneda v. People of the Philippines, G.R. No. 182941, July 3, 2009

88

Robert Sierra y Caneda v. People of the Philippines, supra

89

People of the Philippines v. Halil Gamboa y Esmail, G.R. No. 172707, October 1, 2013

90

Raymund Madali and Rodel Madali v. People of the Philippines, G.R. No. 180380, August 4, 2009

91

Article 68 of the Revised Penal Code provides: “Penalty imposed upon a person under eighteen years of

age – When the offender is a minor under eighteen years and his case is one coming under the provisions

of the paragraphs next to the last of Article 80 of this Code, the following rules shall be observed:

1. Upon a person under fifteen but over nine years of age, who is not exempted from liability by

reason of the court having declared that he acted with discernment, a discretionary penalty

shall be imposed, but always lower by two degrees at least than that prescribed by law for the

crime which he committed.

2. Upon a person over fifteen and under eighteen years of age the penalty next lower than that

prescribed by law shall be imposed, but always in the proper period.”

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE © 2017 22

PERSONAL INJURY AND OFFENDER’S CIVIL LIABILITY UNDER THE PHILIPPINE JURISDICTION

erred in holding Philtranco jointly and severally liable with Calang,

emphasized that Calang was charged criminally before the RTC and,

undisputedly, Philtranco was not a direct party in this case. Since the cause of

action against Calang was based on delict, both the RTC and the CA erred in

holding Philtranco jointly and severally liable with Calang, based on quasi-

delict under Articles 2176 and 2180 of the Civil Code. Articles 2176 and 2180

of the Civil Code pertain to the vicarious liability of an employer for quasi-

delicts that an employee has committed. Such provision of law does not apply

to civil liability arising from delict. If at all, Philtranco’s liability may only be

subsidiary. Article 10292 of the Revised Penal Code states the subsidiary civil

liabilities of innkeepers, tavernkeepers and proprietors of establishments.

Moreover, the said subsidiary liability applies to employers, according to

Article 10393 of the Revised Penal Code.94 The employer becomes ipso facto

subsidiary liable upon his employee's conviction (e.g., his driver) and upon

proof of the latter's insolvency, in the same way that acquittal wipes out not

only the employee's primary civil liability but also his employer's subsidiary

liability for such criminal negligence.95

Under Article 103 of the Revised Penal Code, employers are

subsidiarily liable for the adjudicated civil liabilities of their employees in the

event of the latter’s insolvency. The provisions of the Revised Penal Code on

subsidiary liability are deemed written into the judgments in the cases to

which they are applicable. In the absence of any collusion between the

accused-employee and the offended party, the judgment of conviction should

bind the person who is subsidiarily liable. The decision convicting an

employee in a criminal case is binding and conclusive upon the employer not