Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Alterations of The Lumbar Curve Related To Posture

Uploaded by

AlexiOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Alterations of The Lumbar Curve Related To Posture

Uploaded by

AlexiCopyright:

Available Formats

ALTERATIONS OF THE LUMBAR CURVE RELATED

TO POSTURE AND SEATING *

BY J. JAY KEEGAN, M.D., OMAHA, NEBRASKA

From the Division of \temtro,giCal Surgery, Department of Surgery,

University of Nebraska Co&ge of Medicine, Omaha

INTRODUCTION

One of the most common complaints of persons with low-hack pain is imiability to

sit in comfort, with difficulty in straightening the back on risimug. This is particularly

noticeable after long sitting in a lounge chair, an automobile, or a theater seat, all of which

are supposed to he comfortable. This commomu complaint must. represemut some fundamemital

defect in our conception of the correct sitting position arid in the design of chairs amid seats,

for omily young persons with elastic ligaments amid no back pain can tolerate sitting for

long in the type of seats commonly designed. Older persons, who use chairs more often,

do not have this elasticity amid often sit in discomfort.

This article will present an analysis of the subject of seating iii relatiomi to hack

symptoms. This work is based on a careful clinical study of over 3,000 persons with low-

back complaints, 1,504 of whom have been operated upon for herniatiomu of a lower lumbar

intervertebral disc 4,5,6.7,8,9,10 as well as on a special study of the alteratiomi of the lumbar

curve in various sitting amid standimug positions.

Chair amid seat mamiufacturers have done little scientific study of the anatomical,

physiological, amid pathological factors involved in low-back complaints related to seating.

Too often home-furniture manufacturers have followed standard or classic models of

chairs, designed many years or centuries ago and based largely on the trial-and-error

method, or they have thought more of the luxurious appearamice amid sales appeal of the

chair than of the user’s requirements for comfort. The desigmiers of supposedly comfortable

loumuge chairs have created monstrosities of overstuffed half-beds which provide neither

a comfortable sitting nor a comfortable reclining positiomi, permit no chamige of position,

and are impossible to rise from without assistamuce. Mamiufacturers of seats for offices,

schools, and transportation facilities have made a greater effort to study the comiformation

amid posture needs of the body in relation to seatimig; they have based their designs largely

on anthropometric n3 and on the ideas of desigmiing emigineers, amid! some

progress has been made in this field. The anatomy amid physiology of the problem of sitting

have been excellently presented in a recent monograph by Akerhiom, but there is still a

lack of understanding of the pathological causes of most postural low--back pain related

to seating. It seems time that recently acquired knowledge of the pathology of low-er

lumbar intervertebral discs be applied to the seating problem, amid more correct fumuda-

mental rules be presented for the design of seats for the many persons with low-hack

complaints; these rules are equally applicable to normal persomis.

It now is recognized that the site of most back symptoms arising from postural factors

is in the lower lumbar spine, particularly in the fourth and fifth lumbar intervertebral

discs which commonly degenerate with age under normal weight-bearing, sittimig, amid

stooping strain. Man’s assumption of the erect posture has resulted in a lumbosacral

region poorly comistrueted to support the strain of active physical life. It is a rare person

who reaches middle age without experiemucing some postural low-back pain when sitting

or stooping (Fig. 1). In middle-aged people some loss of elasticity has occurred in inter-

vertebral discs amid ligaments, and obliteration of the lumbar curve temids to force the

degenerated and somewhat separated central portion of the lower lumbar discs posteriorly

* Read at the Meeting of the Clinical Orthopaedic Society, Omaha, Nebraska, October 6, 1951.

VOL. 35-A, NO. 3, JULY 1953 589

.1. .j. kn:n:(;v’-

./ t#{149})) .

1)

hi

A

I-’ i..

C

1 in. I

Tr:u’i I ngs rn ninn r( nn’r I g ngr:L inns ii 1 1)1101 ogra nins, ini:n ( Ic inn order I ( (‘oiliJ nate I inc lunni )osa(’r. I

inn st ain( lung, sitting. :ninn I sIn oi ong. Note tine innarkel flattemniing of I he hum) )osa(’ral n-Inrv(

wIni(-in on’(’tnrs ivinenn t inc sin) )Jn ‘nt is sill inng inn t inc or Ii mary straight n-hair wit in t rumnk ann I tin igins at

right aingl(.

Fiu. 2

I)rawimng to illustrate thu amnatomniv tmnnl mechanics of posterior protrusiomn of a degenerated

fifth lumi air intervertebral (1 ise during sittimng in a right-angled position.

mini: JOURNAL OF BONE AND JOINT SURO1:Ry

ALTERATIONS OF THE LUMBAR CURVE 591

Fic.. 3

F’ig. 3: 1)rawing to illustrate tine

anatonuv an(1 nue(-htuiics of posterior

(‘xtrusion of a (Iegenerated central

fibrocarti lage fronu the fifth lumi air

inntervert(’hral disc, (-aused by by-

drauli(- wedging pressure within the

(use

lift.,

which

Fig.

,

results

4: Comparison

,

from stooping

of tine lumho-

to

(,1’

sacral curve of the dog, the newborn

infant., and tine erect stan(ling adult.

Note the dorsal convexity of the ,

lumbar spine of the newborn infant.,

similar to that. in the quadruped ani-

nml, compare:) with the acquired /( “\

dorsal con(’avitv of tine a(lult lurniatr

Sl)ifle. C z

IW hydraulic pressinme from am-

t.emioi’ ‘edging. ‘IFhis Oc(1.iI’S inn

\‘ti’itl)ld (legmee in sittimig (Fig.

2 ) , amid causes painful st ret.(’lu-

imng of the sensitive postei’iom’

lonigitudimual ligament of the

(lisc, w’ith pain in the mid-limie

()f the low’ back. mu the stooping

l)ositioni (Fig.

3), Part icularly

miliftinug,this hydraulic pres-

stnn’eis greatly inci’eased; it is

estimatetl to be tent to fifteemn Inc.. 4

Ii mes the amommnit of tine weiglnt lifted 2 annd Jm’equennl ly causes m’upt mime ()f I Inc disc annd

ext n’mnsionn ()m’luem’mniat ion of tine loose cemitral fnln’ocai’tilage posterolaterally. If this ext.rusionn

is lan-ge en tough, it causes van’iai )le pm’essum’e on one ovem’lyi mig men-ye root wi thi n the spi nnal

(‘anal, w’itln m’esuhtamit i’a(!iat inng i)aiin inuto one buttock amid lower extm’emit.y; this pain was

foi-mem’ly called sciatica. The nem’ve moot involved in the hack usually can be idenntified

101.. 35A Nnn. 3. JULY 1953

592 J. J. KEEGAN

Fiu. 5

A series of tracimngs from roentgenograms of the lumbosacral spimne, pelvis, and fenuur of

O1i( in(hivi(Iual (Suhjen’t IV), in the lateral recumbent position, only the angle between

trunk :111(1 thighs being vari(’(i. A (liagramnuatic outline of the anterior and posterior thigh

111115(1(8 1.S sul)erinul)ose(l to ShOW that the limited length of these muscles rotates the pelvis

amn(I alters tin(’ lumbar curve. Note the normal position of balanced muscle relaxation at

1:3.5 degrees, with innnrease of the lumi)ar curve as the thighs are brought backward anti

(1(’n’r(’ase of this curve :ts the angle i)etween the thighs and the trunk is reduced.

IL(’(’mml’atelv by t lie (IistIii)imtiOli of paiuu and! miumh sensation, ofteit with additiomial diag-

nnosti(’ sennsOI’V, motor, Itli(l reflex loss iii the extremity. Interestingly, when this rupture

ann(l extrusi()mi of the disc occimu’s, the midi-himie paint in the low back often (lisappears; and

onnlv latem’ttl ‘‘ hip ‘‘ or gluteal pain, together wt.h paul in the lower extremity, is then

pi’esennt, i)e(’ause the 1uij)tlnIe(I sensitive ligamemut over the disc is no longer stretched and

onnlv mnen’ve-(’ompm’essionn l)t111 is present.

Mannv annatomi(’al amnd physiological factors are imuvolved in the developmemit of

low-back symptoms an(l paul from postural causes. The curve of the lumbar spine iii

adult mann is (levelope(l and esIaI)lishe(1 by assumptioni of the erect position for standimig

ann(l walkimng. FIuis dorsal (‘omn(’avity or lumbar lordosis is not presemut. in the newhormi imifant

01’ inn qrmadm’mmped animals (Fig. 4). This foetal curve in man is reversed! during the first

f’ev years of life ‘1ieni the (‘hil(l is learning to walk, because of the inability of the pelvis to

notate nninnet’ (!egmees amid to maintaini alignment with the vertical trumnk. The result is a

siu’rum which is ammgulat N! posteriorly in variable d!egree mi different imidiivi(!iiais amid a

lmnInl)ar cmum’ve w’hich has i)ecome well established in adult life. The fixation of the sacrum in

the pelvis is ann important factor mu placing extra amiterior wedgimug straimi on the lower

lumbar imntervertebral discs when the lumbar curve is flattened by sitting or stooping.

This explaimns why posterior protrusion or extrusion of lumbar intervertebral discs usually

occurs iii the fourth amid fifth lumbar discs arid rarely above this level, as freer movement

of the upper lumbar spimne distributes the force omi these discs more evenly. The posterior

thigh ann! gluteal muscles play an important part in flattening of the lumbar curve in

THE JOURNAL OF BONE AND JOINT SURGERY

ALTERATIONS OF THE LUMBAR CURVE 593

sitting, for they arise from the ischial tuberosity, theposterior aspect of the sacrum amid!

the ilium; and, as the thighs are flexed, they tend to rotate the pelvis by the tension of

their limited length (Fig. 5). Likewise, the anterior trunk-thigh muscles accemituat.e the

lumbar curve imi the erect standing position. The female pelvis is shaped differemitly from

that of the male and flexiomi of the thighs on the trunk is less restricted by heavy muscles

and ligamemits. This permits women to sit at a right angle amid to stoop with less flat-

tening of the lumbar curve. Moreover, the heavier weights lifted by large muscular mcmi

seem to predispose them to low-back symptoms.

STUDY OF NORMAL SUBJECTS

A special study was undertaken to show what happens to the curve of the lumbar

spine imi various sitting amid standing positions. Four normal young persons were selected

for study, two women and two men, with no history or roentgenographic evidlence of

abnormality, in order to show- the normal physiological alteration of the lumbar spine in

various positions. Lateral roentgemiograms of the lumbosacral spimie of these fotmr yoinmug

persons were made in different. positions. Tracings of these were made, the sacrum being

superimposed in each tracing. This gave composite drawings for comparison of the altera-

tion in the lumbosacral curve, the line of the dorsal surface of the vertebral bodies being

used to establish the line of the lumbar curve of each position (Fig. 6). rfhiis line or curve

is somewhat different from the line of the posterior spines of the vemtebrae, or more

accentuated, but it is more representative of the functional alignment of the lumbar

vertel)rae and! intemvertebral dliscs. Drawings from photographs of each body position are

shown w’ith the composite tlrawings. A rather limited number of positions i’ere studlied in

Subjects I and! II in ordler to gain some definition of the chief factors and! findings involved!.

A mon’e complete series of positions, sixteen in number, were stud!ied! in Subject III and

these ‘ere supplemented by a sei-ies of lateral recumbent positions in Subject IV. While

it is (liffictilt. to compam-e the lumbar curves of dlifferent individ!uals, the similarity of the

alten’ations ii’luicii were observed in all four cases and! the fairly complete series in Subject

III seemed adeqimate for the interpretations made. A larger series, includling a study of

pathologically involved lumbar spines, might he more instructive, hut (lid! not seem neces-

sary for the purpose of this paper.

Subject I (IVI. J\I.) is-as a young i’oman of small stature; her height u’a.s five feet

I Innee imiches, her ‘eight \‘as ninety-eight pounls, an(i die had flO recognizable abnormality

of tine lumbosacral Sl)ifle. Five positions for laten’al roentgenograms of this subject is’ere

used (Fig. 6).

It ‘ill 1)1.’ rioted t hat complete oi)htem’ation of the luml)osaeral curu’e o(’(’tmrs omuly

mitime stooping-lifting position, anti that. in this position the fifth lumbar dhsc has changed

front tine narrow’ postem’ior wedge of the standing position to a narrow anterior \Vedige in

the stooping position. This explains why such stooping-lifting strain, by the powerful

hydraulic pressure directed posteriorly (Fig. 3), commonly (‘amuses sudi(len posterior extra-

sion of a diegenerated loose central fibrocartilage of the fotnrth or fifth lumi)ar (!isc. The

neam’est approach to the lumbosacral curve of the standing position is On the high, piVote(i

st()O1. In this position there is an angle of ah)out 135 d!egmees i)etw’een the trunk and thighs

an(1 at the knees. r#{231}r is the position of balanced! relaxation for the mmmseles of tine thighs

an(i legs, an(i it is the position naturally taken i’hen one is lying in bedi on one side, or

comfort.al)ly supine in a hospital bed or a properly fitted lounge chair; it is also the position

so many people take in straight chairs by moving forward in the seat. It represents a more

normal lumbosacral curve than the standing position with its increased lordosis, caused

i)y the pull of the anterior thigh muscles on the pelvis. However, in this position the lumbo-

sacral curve is not ol)hterated, as is shown i)y the straight line dn-awn from the first. lumbar

vertebra to tue most posterior part of the saerum (Fig. 6, B). Moreover, there is no

significant alteration of the shape of the fourth or fifth lumham’ discs in this relaxe(i posit iorn

Vol.. 35-A. NO. 3, .mm. msss

594 J. J. KEEGAN

0:,

C:,

‘Fill: JOURNAL (nF BONE AND J(nJNT snin;i:rty

ALTERATIONS OF THE LUMBAR CURVE 595

Fig. 6: Tracings of

roentgenuograms of the lumbosacral spine of Subject I inn five different positions, tine

sacrunu 1)eing superinupose(1 iii each traeinng, illustrated by body photographs. Note Ixsitioin B as tinat of

nnnost colnfortai)le balance(h mnuscle relaxation witin tine trunk-thigh and the knee angles aI)out. 135 degrees.

‘Fhii.s is tine pinysiologicaHy mnornnal :L(IuIt J)ositioin, inot. tine SLItI1(hiflg erect position A with its exaggerate(l

hninnhar (‘Ui’VQ.

Iig. 7 : Trw’inigs of roennt.geniogranns of tine luminosacral spinne of Subject I I in four different positionns,

tine sa(’runi beiing superinn)osed in (-Item tracimng. The three sittinng positiomns, B, C, and I) are silnilar in tinat

all have tine trunk amid thighs at right alngies, differinng only inn the type of back support and positioln at the

knees. Note that there is not nnuch difference in the considerable flattening of the lumbar curve in these

three sitting positions, indicating that the right-angled trunk-thigiu position is the most important factor

un flattenninng of this curve, although there is some protective preservation of this curve with the well placed

lunnubar back support of position B.

ttmi(i hence no tendency to posterior protrusion of these discs. The slight difference between

the lumbosacral curve of the positions shown in Figure 6, B and C, is due to decrease of

the trunk-thigh angle in position C, which rotates the lower portion of the pelvis further

forward and thus causes some flattening of the curve.

Subject II (R. \V.) was a young woman of medium small stature; her height i’as five

feet five inches, her weight 1 15 pounds, and she had no recognizable abnormality of the

lumbosacral spine. Four positions for lateral roentgenograms were used (Fig. 7). It is to

be noted that there is surprisingly little difference in the flattening of the lumbosacral

curve in the three right-angled sitting positions shown in B, C, and D. The explanation

for this is that rotation of the pelvis by the posterior thigh muscles in the right-angled

sitting position is a greater determinant in obliteration of the lumbosacral curve than is

the absence or presence of low--back support or the position at the knees.

This study emphasizes that the so-called straight or right-angled sitting position

causes considerable strain at the lumbosacral junction and explains w-hy this position

cannot be tolerated for long by anyone with low--back symptoms caused by intervertebral-

(!isc lesions in the low’er lumbar region.

Subject III (J. K.) was a young man of medium stature; his height was five feet

mime inches, his weight 155 pounds, and he had no abnormality of the lumbosacral spine

except comisid!enable lortlosis. A more extensive series of lateral roentgenograms of time

lumbosacral spine was made of this subject in order to compare all important positions

in one person and to add some which had been suggested by the preceding studies of

Subjects I and II. All of the positions used, sixteen in number (Fig. 8), are shown by line

tracings of the posterior lumbosacral vertebral-body curve only, with the sacrum superim-

posed!, to avoid confusion of overlapping vertebral-body lines.

In this series it is surprising to note the slight differences in the lumbosacral curve in

tine first three erect standing positions of A (normal), B (military), and C (relaxed). It

is also noteworthy that in the half-stooped position E, commonly used to carry a heavy

weight on the back, the lumbosacral curve approaches closest to that of the lateral recum-

bent relaxed position D, with trunk-thigh and knee angles about 135 degrees. This relaxed

position can more correctly be called the physiological normal for the lumbar curve than

any erect standing position, but it is seen to retain considerable curve. The squatting

position II, with trunk erect, preserves the lumbosacral curve in considerable degree

because of hyperfiexion of the knees. The maximum flattening of the lumbosacral curve

occurs in the extreme stooping position F, which places great anterior wedging hydraulic

pressure on the lower lumbar intervertebral discs and commonly leads to posterior extru-

sion of the central fibrocartilage. For better comparison of the six standing positions these

are combined in Figure 9, which shows more complete tracings of the lateral roentgeno-

grams. Also in this figure a straight line drawn from the body of the first lumbar vertebra

to the most posterior sacral prominence in position E shows that the lumbosacral curve

is far from flat in this half-stooped position.

Comparison of the lumbosacral curve in the sitting positions in Figure 8, F, G,

I, J, K, L, M, N, and 0, with the standing erect positions, A, B, and C, shows that in

none of the sitting positions does the lumbosacral curve approach very closely to that in

VOL. 35-A, NO. 3, JULY 1953

596 J. J. KEEGAN

‘.2

TilE JOURNAL OF BONE ANI) JOINT SURGERY

ALTERATIONS OF THE LUMBAR CURVE 597

Fig. 8: Tracings from roentgenograms of the lumbosacral spine of Subject ions.III in sixteen differemnt posit

The normal for this individual is established by the lateral recumbent position

and D with the trunk-thigh

knee angles about 135 degrees, as persons lie most comfortably on their sides. The considerable increase of

tine lumbar curve un the three erect standing positions A, B, and C emphasizes that this places considerable

tension on the anterior trunk-thigh muscles and is tiring. The lumbar curve of the somewhat stooped position

E comes nearest that of the relaxed position D, hence is least tiring and safest for heavy load-carrying aind

lifting. Positions F and G show comparable sitting positions of 135 degrees, with lumbar support in position

F and muscle support only in position G. Positions H and I show the influence of hyperfiexion of the knnees

un two right-angled trunk-thigh positions, whereas J, with the knees at a right angle, shows more flattenniing

even with lumbar support. The considerably flattened lumbar curve of position L is interesting, for it repro-

seints the common relaxed lounge-chair position with no lumbar support, conducive to low-back strailn, OV(’iI

though the trunk-thigh angle is 135 degrees. The great difference between this curve and that of positions

F and G, with lumbar curve support, is noteworthy. Position M is the common unsupported right-angled

sitting position, assumed in leanilng slightly forward to work at a desk, while positions 0 and P repres(’mnt

maximum trunk-thigh angle reduction, all with rather marked flattening of the lumbar curve.

Fig. 9: Tracings of roentgenograms of the lumbosacral spine of Subject III in the five standing positioins

for better comparisonu.

the erect standing positions. The nearest approach is in positions F and G, in which tine

trunk-thigh and knee angles are maintained at approximately 135 degrees and the lumbar

curve is supported either by a low-back rest or by muscle support. Positions I, J, K, M,

and N show variations of the common right-angled trunk-thigh sitting position. The

curve of position I shows the influence of flexing the legs beneath the chair w’hen one is

sitting at a right angle, as this relaxes the posterior thigh muscles and helps to preserve

the lumbar curve near that of position G. The difference between positions J and M, witin

amid without back support in the low lumbar area, shows the value of maimitaimiing support

at this level when sitting, but such back support with the legs straight, position N, cannot

overcome the increased pull of the posterior thigh muscles which rotate the pelvis and

flatten the back markedly. Position 0 shows the additional flattening of the lumbar curve

caused by leaning far forward in the sitting position, near the maximum flattenimig observed

in the stooping position P. It should be noted that the common work positions when

seated at a desk, I, J, and M, show considerable flattening of the lumbosacral curve and

would cause anterior wedging pressure on the low’er lumbar intervertebral discs, as well as

posterior protrusion of a degenerated disc (Fig. 2). In none of these sitting positions is

there complete obliteration of the lumbosacral curve as a whole. Lack of recognitiomi of

the posterior prominence of the lower sacrum and the normally recessive fifth lumbar amid

first sacral spines, and failure to consider the lumbosacral curve as a whole, have led to

the incorrect idea that there is rio need of special chair-back support at the lumbosacral

jumiction3 where most pathological low-back conditions and pain develop. The importance

of maintaining the trunk-thigh angle at greater than 90 degrees, with a minimum of 105

degrees, has not been realized in the design of most chairs and seats, for the almost 90-

degree chair back forces consit!erable flattening of the lumbar curve and places strain onu

the lower lumbar discs and ligaments.

Subject IV (WI’. F.) was a young man of medium slender stature, five feet ten inches

tall, and weighing 135 pounds, with no recognizable abnormality of the lumbosacral spine

and no history of low-back symptoms. A series of five lateral roentgenograms of the

lumbosacral spine w’ere made, with the patient recumbent, to show the influence of thigh

extension and flexion on the lumbar curve, the knees being maintained at a constant

90-degree angle and the thorax fixed on the x-ray table. The positions and tracings of

these five roentgenograms of the lumbosacral spine are shown in Figure 10.

In this series it is int.eresting to note the inarkd alteration of the lumbar curve between

positions C and D which represent t.he two comnon seated positions: C with the trunk-

iki’angle,t 135 drees and D with the angle .t 90 degrees. The considerable flattening

of th lumbar curve in the right-angled position explains why the right-angled sitting

position is difficult ,for persons with back disorders. This series also illustrates well the

importance of pull of the anterior and posterior thigh mtiscles on the pelvis, with conse-

quent rotation backward or forward from the hormal, relaxed! 135-degree position C. This

VOL. 35-A. NO. 3. JULY 1953

J. J. KEEGAN

Cl)

TILE JOURNAl. OF’ BONE ANI) JnnINT SIRGEILY

A LTE RATIONS OF THE LUMBAR CURVE 599

1’ig. 10: Tracinngs of m-oent.geinogranis of tine lunnihosacral Spinne of Sui)je(’t I\’ on nyc lateral recunii)elnt

nositioins, I.ini’ sa(’rulni i)eimng su)erinnpos(nl inn (‘a(in tra(-inng. The only varmint in t.inese I)ositions is (leCrea.se of

lime tn-unnk-tinigin anngle, the tinorax ami(I kniecs lneinng mniainntainne(l at comnstanit positionns. Particularly not(-

wortinv is tine great difference in t inc lunni :ti’ (‘lirve i)(Ivee1n 1)osit iomn ( at I 35 (legrecs an(h position 1) at

90 degrees.

Fig 1 1 : Ti’ai’iings of roemntgenograms of tine lunnhosacral spine of SUi)ject IV sinow four (lecreasimngly aingleni

t rumnk-thngii lateral recumbent positiotns be-

t s’eeIn 135 degrees amid 90 degrees, curve F

liNIng at 125 (legrees, G at 115 degrees, H at 105

nlegrees, aind I at 95 degrees.

Fig. 12: A (Iesigrn outline incorporating tin(-

i)asic l’e(luirenneznts for

a conufortable and pro-

Ie(’tiVe s(at., i)ase(I omn knowledge of the ana

t OinIi(’tl, pinysiologi(’al, an(1 )at.hological causes

of low-back dis(Oflufort aln(1 )ain. This basic

(It-sign! is aI)I)li(ai)le to all seats, regardless of

their ext(rlnal fornn or special use. Eleven (Iis-

tinct.ive features are mnumbered 011 the dravinng

aln(l am’e listed belOW vitlu ex)laInatory notes.

1 . Tine inmost distinctive amid importamnt lea-

tUi’O of tinis s(at. designn is pla(-ement of tine

hritnninry iatnk su))port over tine lower lunnham

SI)inne, winer( nnnost postural back symptonis are

lor:iI,enl.

:?. ‘Fhi( Sen’n)in(I inuI)ort.aIit feature is the r-

visiomn of a mnimninnum aingle of 105 degrees

i)et\ve(mn tile trumnk IUn(1 tine tinigh to iuelp p-

serve tine lununbar curve.

3. Tine tinird feature is l)rovisi(In of am open

or re(-essive for tine posteriorlY projecting

saerunnn amid buttocks. This free space permits

(‘n)instalnt contact with tine primary lower lumbar

iEL(’k support.

4. TIne upper limit. of the coinvex I)rinuuary 1’ I(i, 12

lower lumnubar back support inn tine sinort-backed

“stm’aigint” chair sinould be well below the lower angles of tine scapulae. This perinuits unnrestricted posterior

placeinnent of tine sinoulders for relaximng (hainge of position inn the chair.

o. The smoulder support in higlu-backed chaii’s is secondary to the lumubar support, placed ata minimum

aingle of 105 degrees with tine seat. 41 ,. . .

6. Increase of tine angle of the back of the seat is pivoted on a point in line witin the inip joint. Tinis permits

mnuaintemnann’e of contact with the primary lover lumbar support. I1U

7. Tine mnuaxinuum length of tine seat is sixteen inches, measured from the most prominent poimit of tine

lower lumbar support. Tinis allows free space back of the knees for change of 1)OsitiOfl of the legs.

8. Tine ineight of tine seat is sixteen inches, to permit comfortable placement of tine feet on the floor. If

tine seat is made higher for desk or table use, it should be made shorter, fourteen incines for the standard

t.iiirty-imncin-high desk or table, twelve or eight inches for work on a high stool.

LI. The fromnt border of tine seat is curved downward or upholstered; this aids in molding tine thigins over

tine edge of tine seat so tiuat tine feet, cain reach tiue floor. The joining support beneath tine front i)order should

be at a 45-degree angle, so tiuat it will mnot interfere with placement of the feet beneath the seat.

10. Free space below tine seat is provided to allow for placement of the feet beneath the seat in risimng arn(l

for relaxation in sittitng.

.11. A tilt or upward imiclination of 5 degrees for the seat is provided to aid in maintenamnce of prop(-r

position against tine lower lunubar back support.

sei’ies of positions is shown (!iagrammatically in Figure 5, in which the irnportamut nuuiseles

are outlined on tracings of the lumbosacral spine, pelvis, and thighs of this subject.

Because of the great alteration or flattening of the lumbar curve noted! in this sul.)ject

between the angles degrees

of and 90 degrees,

135 a second series of lateral roentgenograms

was made in a similar manner. In this series the trunk-thigh angle was i’etiuced in steps of

10 degn’ees between these angles (Fig. 11). Again the ‘ide difference between the lumbar

cui’ves of 135 degrees and 90 degrees may be seen, with progressive intem-mediate flattemiing

at 125 (legrees (F), 115 degrees (G), and 105 degrees (H), and 90 degm’ees (I), somewhat

greater betw’een the angles of 125 and 115 degrees than before and aften’. This indicates

t.hat considerable flattening of the lumbar curve occurs at 115 degn’ees and at 105 degrees,

emphasizing that the vulnerable lower lumbar spine needs support in these common sitting

l)OSit iOIis.

DISCUSSION

The preceding obsei’vat ions on alterations of the lumbar cum’ve i-elated to posture

and seating emphasize several important factor’s in the causation of discomfort and pain

VOL. 35-A, NO. 3. JULY 1953

j. j. KKEdtN

INCORRECT CORRECT

lic.. 13

I )iagn:n Iii I nn n’nin) n}nasi Z ‘ I Inc nI i fh(’ult v of m’ising ft-omnn am imn(-orre(-t lv desigmne(I loumnge cina i m’ .1

ill n’omnnjnaiisnnmn sit in i n.’nn n(’n’ I l\ ni(’signn(’:l (‘inair B. Tine too bug seat vitin (-lose(i front mn’n’ssi-

tates sli(hnng fnnrvam’ni atm I ext m’emnne flattemnitng of tine lunuinam- (‘Ui’ve inn om’der to misc witinout as-

sistannn’e. I’ine sinnnrt seal :n inn I ontmn fm’ont 1)(’m’mnlit eas’ I)lan-(nnnemnt of feet i)emn(’at in t inc emnl ‘n n

gm’avity it innnut tine hun) n:nn ‘uIvn’ being ilattemned

un I In(- locn’ hmmnul El I’ Oi’ glut t:tl legions anti in t he loven’ extn’ennit ie., pan-t.n(’ulan’lv iii sit t imig

at a might annglc amn(i inn flexing tine l)ack far foi’van’d. \Vluile young iem’somns vithn mnon’nually

(‘last d’ iflten’\’cn’teIJl’tl (Iis(’S ttln(l ligaments can subject their lumbam’ spimues to eonsiden’able

st n’css amid st n’aimn wit lnout nlisconuI’om’t om’ (Iisab)ihity, theme is an inem-easimig tendemncv imi t hose

oven’ t hut v vean’s of’ age 1 nn (‘Xpen’ieli(’e lower’ lIlmh)an’ pain asSO(’iatedi vithi postun’al si nain,

amn(i iintli\’i(hials rtss It)l’ty ycam’s of age without feeling at times some lowen- lumnbai’

son-enness on’ jntiii. It N IiO\V n’c(’ognized that a t’ommnomi (‘RUse of this postural low-back paimi

is J)Ost (-n-ion’ pn’ot i’umsionn of a (legenen’ate(! foum’th or fifth lumbru’ imiten’ven’tebi’al (hs(’,

vIniciu

I (-mm(is t ( ) ( lcV(loj) \Vhn(’nn I Inc 1 1 1 nih Ull’ t’un’ve iS flat temie(i, because of st n’et thing of t he semnsit i ye

)st cn-iom’ loingit mn(linitl I igin nnicmut t lie disc

()Vti (E’igs. 1 and 2) . ‘f\’pidall\’ sucln a l)d1SOmi

fimnds it (iifh(tilt I n) st n-night (0 t Inc ba(’k ti’tem sittimig ion’ long in an or’dinan’v cinaim’, because

( )f t lie slovmnc-s ‘it In \vlni(’ln t Inc 1)n-ot m’um(limig disc resumes its non-mal shape. When ext ritsionu

01 t nue hnem’mniat iOni oh I inc nl(’gcnnen-ate(! loose central fibn-ocartilage oecum’s w’ithi i)n’essumn(’ OIl

a mi’n’’e moot Fig. 3 ), I hn( humnnihan’ cum’ve becomes set. on’ fixed imu a somewhat. flattened posi-

I 1( )mn, I)(’(tli5(’ 1 il(’ int’n-mnia I en I t issue caIiIiOt m’etumn t 0 t inc centem’ of t lie (usc flfl( I m’ennains

I )11 nt iv \V( ige( I in I i(’ I nst

t ( Ii ( )1’ J )1t i ( mi of t lie (lis(’ 1u nt hem’ flexiomi or’ flat temui mug of the

.

luniilnin sI)ini(’, as inn sit t imig 01 st on)pimng, stn’et(’hes the sensitized oven-lying nei’vc moot an(l

1iicle1iS(5 IIcn’’,’(.’-m’OOt unit It in)nu tlIi(l glint cal and lowen’-ext rennitv pain. Moi’eo’en-, stamu(ling

el’C(’t 01’ b(’mu(linng h n-knt’n Is oft cmi (-auses incm’ease(l nen’ve-n’oot l)ain t Inc muriss of

hiem’miiat d(l I issue is lange t ni 1 lea yes lit tle space for’ t he oven’lyinig miem’ve i’oot.. ‘Finns i I is

sePmi thnat, (lulling sit I imug, smlj)pOl’t ()f t lie low’em’ lunlh)al- spilne ovem’ the foum’th and fift In lunuban-

(usd5 iS \‘d’l’\’ imiuI)om’t:tnnt fnnm’ I)(’n’sOIms \Vit ii any (legdIiem’1ttiOmi Oi’ ten(lemicy to l)Ost cmliii l)m’ot mu-

sin )Ii of 1 in(sc imit (‘I’V(l’I (‘I )1L 1 lis(’s. \\hnen ext i’usiomu 01’ t n-ne hnei’muiat ion inas oc(’u 11(0 1, t he

pat iemit inns tO mnaun t a inn I sn O1ie\Vlnat fixN! posit ion of fom’vam’ I flexiomi, titus attempt i mig t o

mel ieve t inc l)’cn 11 nnnn t In #{149} mncn’vc 1( )( )t as miili(’li as possible. loncing this patient imito a nnv

ot lien’ posit i()In b\’ maIliI)mll:lt iomn, t n’act lOu, 01’ bm’a(’e incn’eases mis paimu and is liable to fmnnt lien’

tine ext i’mnsin nun amut I In) t-amnst (‘onil)het e ln )ss of funct ion 0! tint’ mnci’ve i-oot.

As tin is st mn(i\’ n)f alt cia t ion of tine lumban’ curve in mnon-mttl subjects pI’ogl-cssN I, it

becanie inucn’easimngiy evitiemnt that the optimum or’ physiologically non’mal positiomu of’ the

liii: J)URNAL OF’ BONE AND JOINI’ SURGERY

ALTERATIONS OF THE LUMBAR CURVE 601

tdtnlt spinie is with the trunk-thigh angle and the knee angle at approximately 135 degrees,

anm(l that. mu this j)osition there is considerable curve in the himmbar spine. This is the posi-

tionn of I)RIRflcC(i nimnst’le relaxation, w’ith the intervertel)ral discs stabilized! in their normal

a(hnlt slnape. Alteratiomn of this normal adult lumbar curve, either forward in sitting and

st.oO)ing, or backivan-d in standing em’ect, places greaten’ i’edging strain on the lower lumbar

discs than on those above, because of the tensing of the long thigh muscles of the opposite

side and fixation or rotation of the pelvis (Fig. 5). Consequently it is important to recog-

nize that sitting positions which tend to flatten or obliterate the lumbar curve by decreas-

ing the angle between the thighs and trunk soon become uncomfortable and cannot be

tolerated for long I)y persons with degenerated intervertebral discs in the lower lumbar

m’egiomm. With this basic know-ledge of alterations of the lumbosacral curve in standing and

sitting positions ant! recognition of the common cause of postural low-back pain, it is

possii)le to establish correct rules for the design of chairs, applicable to all seats regardless

of tlnein’ I)uu’pose, size, or cost. Such a design outline is shown in Figure 12, with the several

requirenients numbered in order of their importance.

r#{231}j most important requirement of a correct seat for protection of the vulnerable

loiveu’ lumbar intervertebral discs is placement of the primary 1)aek support over the lower

lumbar region (Fig. 1 2, 1) Free space

. or a sharply recessive curve is needed below the

lumbosacn’al juncture (Fig. 12, 3) to accommodate the posteriorly projecting sacrum and

I)uttOcks. The surface of the lower lumbar support should be convex, in conformity with

the normal physiological lumbar curve. In small, straight chairs it is better to have the

back support end at the thoracolumbar juncture below the lower angles of the scapulae

(Fig. 12, 4), as this permits occasional relaxing restoration of the normal lumbar curve by

allowing the person to lean backward without shoulder blocking. Permissive change of

position in sitting ii-as considered by Akerblom the most important requirement of a

(‘omiufom’table seat..

Shoulder’ suppon’t (Fig. 12, 5) has i)een overemphasized in the design of seats; it is

rueeessamy flly in semiiin’eclining chairs and should always he made secondary to the primary

s11I)pOI’t. of the 1OW’eu lumbar cunve. In the semireclining positions the abdominal weight

tendls to flatten time lumbar curve, so that there is additional need for lumbar support,

although increase of the trunk-thigh angle and tension of the anterior muscles help to

preserve the lumbar curve in this position. This change of position in adjustable seats

should be l)ivotedl on the axis of the hip joint.

rn second important requirement for a correct seat is allowance of a minimum trunk-

thigh amigle of 105 degrees in high-backed chairs (Fig. 12, 2), in order to prevent too much

uncomfortable flattening of the physiologically normal lumbosacral curve in the adult.

It is impossible to sit in the common straight chair with a 90-degree or 95-degree angle

I)etw’cen the bttek and the seat without considerable flattening of the lumbosacral curve

rind! painful posterior’ protrusion of degenerated lower lumbar intervertebral discs. It is a

(‘ommiuon ol)seryation that people who sit in this type of almost right-angled chair tend to

slide fom’waid in the seat for more comfort. Thi is because sliding forward increases the

trunk-thigh angle, restores the lumbar curve, and reduces posterior protrusion strain on

the low’er intervertebral

lurni)am’ discs.

Correct design of the seat of the chair is as important as that of the back of the chair

and is 5t11)ject to as many misconceptions of its form and function. rfhe most important

reqimirenuent is that it be short, never over sixteen inches in length (Fig. 12, 7), the length

i)eing m’educed as the seat is made higher. People sit most naturally and comfortably on

their buttocks, riot on their thighs. Th ischial tuberosities of the pelvis furnish the bone

support of the trunk w’eight in sitting. Molding or cushioning the seat helps to distribute

tine weight more widely. It is not comfortable or useful to extend the seat beyont! the mid-

thigh region beneath the tendons hack of the knees. At least four inches of free space are

necessary there to permit some molding of the soft portion of the thighs when the knees

are partly extended or flexed, for relaxation and change of position, and for flexion of the

Vol.. 35-A, NO. 3. JULY 953

602 .r. j. KEEGAN

knees in rising. The front space beneath the seat should always be left open or receding at an

angle of not less than 45 dlegrees (Fig. 12, 9), in order to permit placement of the feet beneath

the seatfor relaxation and! as an aid in rising. It is impossible to get out of a seat which is too

long and has a closet! or wide vertical front border, except by excessive back flexion and

sliding forward to place the center of gravity over the feet in front of the chair (Fig. 13, A).

The much greater ease of rising from a proper short open-front seat is shown in Figure 13,

B. Some tilting of the seat is desirable, about 5 degrees above the horizontal in front (Fig.

12, 11), for ease in maintaining position and for contact with the back of the chair, but this

inclination should not be so much nor the seat so long and high that the average short

person cannot rest the feet comfortably on the floor with the knees partly extended or

flexed.

The height of the seat from the floor may vary according to purpose, the seat neces-

sarily becoming shorter tLS the distance from the floor is increased, so that the thighs can

be directed mom’e downward and the feet can reach the floor. If the seat is of the maximum

sixteen-inch length, tine height should not be more than sixteen inches. This permits the

average short person to reach the floor with his feet and to be able to extend or flex the

knees moderately for needed change of position. It is easier for the long-legged person to

adjust to a low’ seat than for the short person to adjust to a high seat. Seats for work or

eating over the standard thirty-inch-high desk or table need to be eighteen inches high but

not over fourteen inches in depth, to permit the feet to reach the floor comfortably. The

reason that sitting on a high stool with a short seat is more comfortable and protective for

work over high work tables is that the increased angle between the thighs and the trunk

helps to preserve the normal lumbosacral curve. Flexion of the knees beneath the chair,

commonly noted in desk workers, likewise helps to preserve the lumbar curve in sitting,

by relaxing the posterior trunk-thigh muscles.

Another important requirement is that a sixteen-inch distance be kept from the eyes

to the top of a desk or work-table surface, as reading glasses are regularly adjusted! for

this focal length. While youmig persons can read at a much closer range than this, it is tiring

for their eyes, and older persons with fixed eye lenses seriously need the sixteen-inch read-

ing distance to which their glasses are adjusted. The standard height of desks and tables is

thirty inches, some desks i)eing adjustable to twenty-eight inches; card tables are regularly

this latter height. The aven’age person sitting in the ordinary straight chair with a seat

height of eighteen inches finds that his eyes are too close to the thirty-inch-high desk or

table top for comfortable reading and usually resorts to leaning backward somewhat, both

to increase his reading distance and to enlarge the angle between trunk and thighs for

more comfort when sitting. For work directly over a desk it is better to maintain the desk

height of thirty inches, but to elevate the seat to twenty inches and reduce its length

to fourteen inches, which permits maintenance of a larger trunk-thigh angle without

uncomfortable pressure on the seat edge beneath the mid-thigh region. Desk workers

now’ are usually supplied with a “posture” chair which has an adjustable seat height and

fourteen inches of seat length ; this should overcome the difficulty of maintaining the

proper reading distance of sixteen inches from their work and a desirable trunk-thigh angle

of 105 degrees or more. however, most desks are made with such a deep center drawer that

it is impossible to sit high enough to maintain proper reading distance, because of contact

of the thighs against the drawer. This drawer never should be over two inches in depth;

it is better omitted entirely, as it cannot be opened when the worker is seated at the desk.

School desks are commonly made with a deep center receptacle, which seriously handicaps

the shorter child in maintaining the correct reading distance of sixteen inches.

Molding or cushioning of the seat is desirable for better distribution of weight over

the entire buttocks; this is particularly needed for thin persons in whom pressure pain tends

to develop over the ischial tuberosities. The front edge of the seat should be turned down

or soft-cushioned, in order to permit (‘hiange of position of the legs without uncomfortable

THE JOURNAL OF BONE AND JOINT SURGERY

ALTERATIONS OF THE LUMBAR CURVE 603

ri(Ige pressure i)eneat.h the thighs. The covering of upholstered chairs should be porous

ant! rough to provide ventilation and fixation. The present tendency to use impervious

smooth plastic covering, because of w’earing and cleaning advantages, causes uncom-

fortable moist heat and wrinkling of clothing. The w’idth of the seat can be varied to fit

individual needs. The arm rest should provide support beneath the soft muscle part of

the forearm, not beneath the elbow’s, as the latter causes uncomfortable bone and ulnar-

nerve pressure, sometimes leading to paralysis of this nerve. Consequently there should he

an open or low-er space directly beneath the elbow.

The form and measurements of a functionally correct chair should he based on

complete knowledge of the anatomical, physiological, and pathological factors involved

in low-hack pain related to seating, not on ant.hropometric measurements or on trial-and-

error methods of testing w’ith normal persons. A subsequent article will deal with this

suh)ject in a more specific manner, with discussion of the faults of types of seats in common

use and presentation of correct seat designs.

CONCLUSIONS

The most common cause of low-hack pain related to seating is posterior protrusion

or extrusion of lower lumbar intervertebral discs.

The normal curve of the lumbar spine in adult man is determinet! by maintenance of

the trunk-thigh and the knee angles at approximately 135 degrees.

Alteration of this normal lumbar curve, eithem an increase in standing erect or a

d!eCrease in sitting or stooping, is caused largely by the himitet! length anti consequent

pull of the trunk-thigh muscles of the opposite side.

The most important postum’al factor in the causation of low-hack pain in sitting is

t!ecrease of the trunk-thigh angle an(1 consequent flattening of the lumbar curve.

The next most. impom’tant cause of low-back pain in sitting is lack of primary hack

support O”,’eU the vulneral)le low’er lumbar intervertebral discs.

At!ded factor’s of comfom’t in seating are the shortness of the seat, a round!et! narrow

front i)or(iem’, an open space beneath for better positioning of the legs, and! permissive

change of position in the seat.

The design of all seats, regardless of model or size, should he based on this know-ledge.

NOTE: Tine aut.inor wishes to express his appreciation to the Department of Ra(Iiology and Physical

Medicine of the Umniversitv of Nebraska College of Medicinne, Omaina, for the roennt.genograms used in this

study, and to tine medical students who volunteered as subjects for the roentgenogrtms.

REFERENCES

1. AKERBI.OM, B. : Standing and Sitting Posture. Stockholm, A. B. Nordiska Bokinandeln, 1948.

2. BRADFORD, F. K., an(I SPURLLN’G, It. G. : The Intervertebral Disc. With Special Referemnee to Rupture

of the Annulus Fibrosus with Herniatioin of the Nucleus Pulposus. Ed. 2, Springfield, Ill., Charles C.

Thomas, 1945.

3. H0OTON, E. A. : A Survey un Seating. Gardmuer, Mass., Heywood Wakefield Co., 1945.

4. I%.EEGAN, J. J., aind FINLAYSON, A. I. : Low Back an(1 Sciatic Pain Caused by Intervertebral Disc Hernia-

tion. Nebraska State Med. J., 25: 179-183, 1938.

5. KEEGAN, J. J. : J)ermnatome Hypalgesia Associated with Herniation of Intervertei)ral Disk. Arch. Neurol.

and Psyciniat., 50: 67-83, 1943.

6. KEEGAN, J. J.: Neurosurgical Interpretationn of Dermatome Hypalgesia with Herniatiorn of the Lumi)ar

Inntervertei)ral Disc. J. Bone and Joint Surg., 26: 238-248, Apr. 1944.

7. KEEGAN, J. J.: Diagnosis of Hermniation of Lumbar Intervertebral Discs by Xeurologic Signs. J. Am.

Med. Assn., 126: 868-873, 1944.

8. KEEGAN, J. J.: Dermatome Hypalgesia with Posterolateral Herniation of Lower Cervical Intervertebral

I)isc. J. N’eurosurg., 4: 115-139, 1947.

1. kEEGAN, J. J.: Relatiomns of Nerve Itoots to Abnnornualitiesof Lumnnban- amnd Cervical Pou’tions of the

Spine. An’in. Surg., 55: 246-270, 1947.

10. KEEGAN, J. J., amid (.RRE’vr, F. C.: Tine Segnnuenntal l)isti’ibutiomn of tine Cutamneous Nen’ves in the T4innlns

of Man. Anat. Rec., 102: 409-437, 1948.

“OT.. 35-A, NO. 3. JUlY 953

You might also like

- An Essential Guide for Scoliosis and a Healthy Pregnancy: Month-by-month, everything you need to know about taking care of your spine and baby.From EverandAn Essential Guide for Scoliosis and a Healthy Pregnancy: Month-by-month, everything you need to know about taking care of your spine and baby.No ratings yet

- Documentation For The Physical Therapist Assistant 4th EdDocument280 pagesDocumentation For The Physical Therapist Assistant 4th Edpipit sopianNo ratings yet

- A Review of The Literature On Evidence-Based Practice in PhysicalDocument10 pagesA Review of The Literature On Evidence-Based Practice in PhysicalDyah SafitriNo ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Practice: Development and Content of The Dutch National Practice Guidelines For Physical Therapy in Patients With Low Back PainDocument11 pagesEvidence-Based Practice: Development and Content of The Dutch National Practice Guidelines For Physical Therapy in Patients With Low Back PainrapannikaNo ratings yet

- Libro IsicoDocument111 pagesLibro Isicoiguija6769No ratings yet

- A Case Study Utilizing Vojta Dynamic Neuromuscular Stabilization Therapy To Control Symptoms of A Chronic Migraine Sufferer 2011 Journal of Bodywork ADocument4 pagesA Case Study Utilizing Vojta Dynamic Neuromuscular Stabilization Therapy To Control Symptoms of A Chronic Migraine Sufferer 2011 Journal of Bodywork AJose J.No ratings yet

- Evidenced Based Practice in Physical TherapyDocument3 pagesEvidenced Based Practice in Physical TherapyAndrews Milton100% (1)

- Proprioception in Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation2Document10 pagesProprioception in Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation2Santiago Cubillos EscobarNo ratings yet

- De Novo Scoliosis: Ashish Patel Frank Schwab Jean-Pierre FarcyDocument9 pagesDe Novo Scoliosis: Ashish Patel Frank Schwab Jean-Pierre Farcymetasoniko81No ratings yet

- Myofascial ReleaseDocument8 pagesMyofascial Releaseprokin_martinezNo ratings yet

- Sanatate KineticaDocument14 pagesSanatate KineticacrinaconstantNo ratings yet

- Segmental Instability of The Lumbar SpineDocument13 pagesSegmental Instability of The Lumbar Spineiss kim100% (1)

- Traction PDFDocument31 pagesTraction PDFrushaliNo ratings yet

- Rehab of Patients With HemiplegiaDocument2 pagesRehab of Patients With HemiplegiaMilijana D. DelevićNo ratings yet

- Introduction To EMG & EMG Guided Manual Therapy of Lumbar SpineDocument45 pagesIntroduction To EMG & EMG Guided Manual Therapy of Lumbar SpineDomingo A. Rodriguez RamirezNo ratings yet

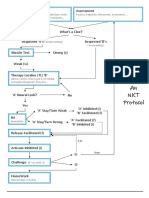

- NKT FlowChart - PDF Version 1 PDFDocument2 pagesNKT FlowChart - PDF Version 1 PDFJay SarkNo ratings yet

- 1 1681 1 PDFDocument38 pages1 1681 1 PDFagung satrioNo ratings yet

- Lab: Motor Pattern Assessment Screening & Diagnosis: Albert J Kozar DO, FAOASM, RMSKDocument72 pagesLab: Motor Pattern Assessment Screening & Diagnosis: Albert J Kozar DO, FAOASM, RMSKRukaphuongNo ratings yet

- Muscle Training Pelvic Floor Muscle DysfunctionsDocument46 pagesMuscle Training Pelvic Floor Muscle Dysfunctionseraagustin75No ratings yet

- SCOLIOSIS Straightening Is Possible - DR Jan Polak - Ebook PDFDocument40 pagesSCOLIOSIS Straightening Is Possible - DR Jan Polak - Ebook PDFLuigi PolitoNo ratings yet

- Reflex Control of The Spine and Posture - A Review of The Literature From A Chiropractic PerspectiveDocument18 pagesReflex Control of The Spine and Posture - A Review of The Literature From A Chiropractic PerspectiveWeeHoe LimNo ratings yet

- 52 Page PDF PF PPT Neurophysiological Effects of Spinal Manual Therapy in The Upper Extremity - ChuDocument52 pages52 Page PDF PF PPT Neurophysiological Effects of Spinal Manual Therapy in The Upper Extremity - ChuDenise MathreNo ratings yet

- Functional TrainingDocument32 pagesFunctional TrainingEsteban Bustamante100% (1)

- The Bobath Concept inDocument12 pagesThe Bobath Concept inCedricFernandezNo ratings yet

- Jospt 2020 0301Document73 pagesJospt 2020 0301CarlosNo ratings yet

- Shoulder Impingement GuidelinesDocument3 pagesShoulder Impingement GuidelinesTasha MillerNo ratings yet

- Strategies To Improve Motor LearningDocument18 pagesStrategies To Improve Motor LearningUriel TabigueNo ratings yet

- Anabolic Steroids: Use and AbuseDocument79 pagesAnabolic Steroids: Use and AbuseMasaru NatsuNo ratings yet

- Theoretical - Biomechanics - Klika - 2011 - in Tech PDFDocument415 pagesTheoretical - Biomechanics - Klika - 2011 - in Tech PDFraarorNo ratings yet

- Patello Femoral ExercisesDocument4 pagesPatello Femoral ExercisescandraNo ratings yet

- A Kinetic Chain Approach For Shoulder RehabDocument9 pagesA Kinetic Chain Approach For Shoulder RehabRicardo QuezadaNo ratings yet

- Asana Based Exercises Low Back PainDocument14 pagesAsana Based Exercises Low Back PainAutumn Carter100% (1)

- Kozar ScienceOfMotorControlLectureDocument114 pagesKozar ScienceOfMotorControlLectureMari PaoNo ratings yet

- The Shoulder PainDocument14 pagesThe Shoulder PainLev KalikaNo ratings yet

- Jaspal R Singh, M.D.: Department of Rehabilitation MedicineDocument2 pagesJaspal R Singh, M.D.: Department of Rehabilitation MedicineshikhaNo ratings yet

- TBI Report To Congress Epi and Rehab-ADocument72 pagesTBI Report To Congress Epi and Rehab-AEric GibsonNo ratings yet

- Materi Joint ManipulationDocument3 pagesMateri Joint ManipulationAnDi Anggara PeramanaNo ratings yet

- Mckenzie Evaluation and Treatment For Lumbar Dysfunction and ANRDocument36 pagesMckenzie Evaluation and Treatment For Lumbar Dysfunction and ANRMaluNo ratings yet

- Ultrasound TherapyDocument3 pagesUltrasound Therapyليلى مسلمة100% (1)

- Care of Patients With Problems of The CNS-Spinal CordDocument34 pagesCare of Patients With Problems of The CNS-Spinal CordjacobNo ratings yet

- Bobath ArticleDocument8 pagesBobath ArticleChristopher Chew Dian MingNo ratings yet

- Kibler Scapular DyskinesisDocument10 pagesKibler Scapular Dyskinesisנתנאל מושקוביץ100% (5)

- Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: An Update On The Epidemiology, Diagnosis and TreatmentDocument15 pagesLumbar Spinal Stenosis: An Update On The Epidemiology, Diagnosis and TreatmentNoor HadiNo ratings yet

- ParkinsonDocument10 pagesParkinson46238148No ratings yet

- Rehabilitation AmbulationDocument14 pagesRehabilitation AmbulationDeborah SalinasNo ratings yet

- Journal 0606Document32 pagesJournal 0606cristina lunguNo ratings yet

- Subacromial Impingement Syndrome and Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy: The Dilemma of DiagnosisDocument4 pagesSubacromial Impingement Syndrome and Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy: The Dilemma of DiagnosisTomBramboNo ratings yet

- Flash e Hogan (1985) PDFDocument16 pagesFlash e Hogan (1985) PDFDunga PessoaNo ratings yet

- Kaltenborn Evjenth Concept of OMTDocument34 pagesKaltenborn Evjenth Concept of OMTJaan100% (1)

- Tampa Scale Kinesiophobia PDFDocument2 pagesTampa Scale Kinesiophobia PDFlizNo ratings yet

- Modified Timed Up and Go TestDocument2 pagesModified Timed Up and Go TestStephanie WrightNo ratings yet

- Biomechanical Considerations in Patellofemoral Joint RehabilitationDocument7 pagesBiomechanical Considerations in Patellofemoral Joint RehabilitationJ Roberto Meza OntiverosNo ratings yet

- Acl Rehab ProgrammeDocument8 pagesAcl Rehab ProgrammePengintaiNo ratings yet

- 香港脊醫 Hong Kong Chiropractors Sep 2016Document6 pages香港脊醫 Hong Kong Chiropractors Sep 2016CDAHKNo ratings yet

- Kaltenborn 1993Document5 pagesKaltenborn 1993hari vijayNo ratings yet

- Functional Evaluative Tests RevisedDocument4 pagesFunctional Evaluative Tests RevisedaocannonNo ratings yet

- MC Kenzie: Diagnostic, Prognostic, Therapeutic, and ProphylacticDocument19 pagesMC Kenzie: Diagnostic, Prognostic, Therapeutic, and ProphylacticEvaNo ratings yet

- OCR - Command Word DefinitionsDocument5 pagesOCR - Command Word DefinitionsSinjini SarkarNo ratings yet

- Temporal Fascia in Diced Cartilage-Fascia GraftsDocument1 pageTemporal Fascia in Diced Cartilage-Fascia GraftsAlexiNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Mulligan ConcepteDocument2 pagesIntroduction To Mulligan ConcepteAlexiNo ratings yet

- Myofascial Meridians PDFDocument9 pagesMyofascial Meridians PDFPedja Ley100% (3)

- Anatomy Trains PDFDocument9 pagesAnatomy Trains PDFAlexi100% (2)

- The Mulligan Concept of Manual Therapy 9780729541596 Hing Samplechapter PDFDocument30 pagesThe Mulligan Concept of Manual Therapy 9780729541596 Hing Samplechapter PDFAlexi0% (1)

- International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics: Sangeun Jin, Gary A. MirkaDocument5 pagesInternational Journal of Industrial Ergonomics: Sangeun Jin, Gary A. MirkaAlexiNo ratings yet

- Lung ModelDocument6 pagesLung ModelGülşah Öztürk KadıhasanoğluNo ratings yet

- Possession 'SDocument2 pagesPossession 'SazlinNo ratings yet

- Animales en La Cultura YorubaDocument9 pagesAnimales en La Cultura Yorubaaganju999No ratings yet

- Fluid and Electrolytes1Document7 pagesFluid and Electrolytes1Charl PabillonNo ratings yet

- Ai Chi - Meridians1Document7 pagesAi Chi - Meridians1sale18100% (1)

- The PhiladelphiaDocument6 pagesThe PhiladelphiaRyan CaddiganNo ratings yet

- Public SpeakingDocument490 pagesPublic SpeakingDewa Putu Tagel100% (8)

- Sensory Play Activities Kids Will LoveDocument5 pagesSensory Play Activities Kids Will LoveGoh KokMingNo ratings yet

- Nervous System Endocrine System and Reproductive SystemDocument5 pagesNervous System Endocrine System and Reproductive SystemMcdaryl Inmenzo Lleno50% (2)

- Assigment On Inheritance & Variation (MCQ)Document25 pagesAssigment On Inheritance & Variation (MCQ)FritzNo ratings yet

- Hi-Yield Notes in Im & PediaDocument20 pagesHi-Yield Notes in Im & PediaJohn Christopher LucesNo ratings yet

- Quiz On Epithelial and Connective TissueDocument7 pagesQuiz On Epithelial and Connective TissueJoshua Ty Cayetano100% (1)

- Shampoo Condition and Treat The Hair and Scalp: Unit Gh8Document31 pagesShampoo Condition and Treat The Hair and Scalp: Unit Gh8Em JayNo ratings yet

- Wintrobe Anemia On Chronic DiseaseDocument31 pagesWintrobe Anemia On Chronic DiseaseDistro ThedocsNo ratings yet

- 3rd Summative Test SCIENCE 5Document3 pages3rd Summative Test SCIENCE 5Jeje Angeles100% (1)

- Environmental Aspects of Domestic Cat Care and ManagementDocument8 pagesEnvironmental Aspects of Domestic Cat Care and ManagementAllyssa ReadsNo ratings yet

- MUST To KNOW in HematologyDocument40 pagesMUST To KNOW in HematologyPatricia Yutuc90% (10)

- Make Money With VestigeDocument46 pagesMake Money With Vestigejameser123100% (1)

- 0610 s17 QP 31Document24 pages0610 s17 QP 31BioScMentor-1No ratings yet

- Case 1Document6 pagesCase 1Nico AguilaNo ratings yet

- Villanueva General Ordinance of 2009Document148 pagesVillanueva General Ordinance of 2009Rogelio E. SabalbaroNo ratings yet

- Post Thoracotomy Physiotherapy ManagementDocument25 pagesPost Thoracotomy Physiotherapy ManagementSiva Shanmugam100% (5)

- Gastro Lab ManualDocument28 pagesGastro Lab ManualYeniNo ratings yet

- Pneumonia Concept Map - KPoindexterDocument1 pagePneumonia Concept Map - KPoindexterKatie_Poindext_5154100% (2)

- Genetics Icar1Document18 pagesGenetics Icar1elanthamizhmaranNo ratings yet

- LPR Its Not GerdDocument3 pagesLPR Its Not GerdWilhelm HeinleinNo ratings yet

- Skilled Birth Attendant PostersDocument16 pagesSkilled Birth Attendant PostersPrabir Kumar Chatterjee100% (1)

- Medical Parasitology in The Philippines 3rd Ed PDFDocument535 pagesMedical Parasitology in The Philippines 3rd Ed PDFroland mamburam75% (16)

- Traducere in Engleza Site Spring Dental Mihaela VelcuDocument11 pagesTraducere in Engleza Site Spring Dental Mihaela VelcuFlorin Cornel VelcuNo ratings yet

- HIV-Associated Opportunistic Infections of The CNSDocument13 pagesHIV-Associated Opportunistic Infections of The CNSmauroignacioNo ratings yet

- The Bridesmaid: The addictive psychological thriller that everyone is talking aboutFrom EverandThe Bridesmaid: The addictive psychological thriller that everyone is talking aboutRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (132)

- How to Talk to Anyone: Learn the Secrets of Good Communication and the Little Tricks for Big Success in RelationshipFrom EverandHow to Talk to Anyone: Learn the Secrets of Good Communication and the Little Tricks for Big Success in RelationshipRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1135)

- Breaking the Habit of Being YourselfFrom EverandBreaking the Habit of Being YourselfRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1460)

- Love Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)From EverandLove Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDFrom EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- The Energy Codes: The 7-Step System to Awaken Your Spirit, Heal Your Body, and Live Your Best LifeFrom EverandThe Energy Codes: The 7-Step System to Awaken Your Spirit, Heal Your Body, and Live Your Best LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (159)

- Manipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesFrom EverandManipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1412)

- Briefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndFrom EverandBriefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndNo ratings yet

- Neville Goddard Master Course to Manifest Your Desires Into Reality Using The Law of Attraction: Learn the Secret to Overcoming Your Current Problems and Limitations, Attaining Your Goals, and Achieving Health, Wealth, Happiness and Success!From EverandNeville Goddard Master Course to Manifest Your Desires Into Reality Using The Law of Attraction: Learn the Secret to Overcoming Your Current Problems and Limitations, Attaining Your Goals, and Achieving Health, Wealth, Happiness and Success!Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (285)

- Follow your interests: This will make you feel better about yourself and what you can do.: inspiration and wisdom for achieving a fulfilling life.From EverandFollow your interests: This will make you feel better about yourself and what you can do.: inspiration and wisdom for achieving a fulfilling life.No ratings yet

- Prisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldFrom EverandPrisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1146)

- Raising Grateful Kids in an Entitled World: How One Family Learned That Saying No Can Lead to Life's Biggest YesFrom EverandRaising Grateful Kids in an Entitled World: How One Family Learned That Saying No Can Lead to Life's Biggest YesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (108)

- Peaceful Sleep Hypnosis: Meditate & RelaxFrom EverandPeaceful Sleep Hypnosis: Meditate & RelaxRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (144)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossFrom EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Deep Sleep Hypnosis: Guided Meditation For Sleep & HealingFrom EverandDeep Sleep Hypnosis: Guided Meditation For Sleep & HealingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (104)

- For Women Only, Revised and Updated Edition: What You Need to Know About the Inner Lives of MenFrom EverandFor Women Only, Revised and Updated Edition: What You Need to Know About the Inner Lives of MenRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (272)

- My Little Brother: The unputdownable, page-turning psychological thriller from Diane SaxonFrom EverandMy Little Brother: The unputdownable, page-turning psychological thriller from Diane SaxonRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (39)

- The Diabetes Code: Prevent and Reverse Type 2 Diabetes NaturallyFrom EverandThe Diabetes Code: Prevent and Reverse Type 2 Diabetes NaturallyRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- The Guilty Wife: A gripping addictive psychological suspense thriller with a twist you won’t see comingFrom EverandThe Guilty Wife: A gripping addictive psychological suspense thriller with a twist you won’t see comingRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- His Needs, Her Needs: Building a Marriage That LastsFrom EverandHis Needs, Her Needs: Building a Marriage That LastsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (100)

- The House Mate: A gripping psychological thriller you won't be able to put downFrom EverandThe House Mate: A gripping psychological thriller you won't be able to put downRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (127)

- Summary of The 4-Hour Body: An Uncommon Guide to Rapid Fat-Loss, Incredible Sex, and Becoming Superhuman by Timothy FerrissFrom EverandSummary of The 4-Hour Body: An Uncommon Guide to Rapid Fat-Loss, Incredible Sex, and Becoming Superhuman by Timothy FerrissRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (82)

- The Three Waves of Volunteers & The New EarthFrom EverandThe Three Waves of Volunteers & The New EarthRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (179)

- The Waitress: The gripping, edge-of-your-seat psychological thriller from the bestselling author of The BridesmaidFrom EverandThe Waitress: The gripping, edge-of-your-seat psychological thriller from the bestselling author of The BridesmaidRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (65)

- Summary of The Art of Seduction by Robert GreeneFrom EverandSummary of The Art of Seduction by Robert GreeneRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (46)