Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Internal Criticism

Uploaded by

monojdeka50%(2)50% found this document useful (2 votes)

409 views9 pagesInternal Criticism

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentInternal Criticism

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

50%(2)50% found this document useful (2 votes)

409 views9 pagesInternal Criticism

Uploaded by

monojdekaInternal Criticism

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 9

\

Internal Criticism: A Brief Reflection

Copyright 2002 José Cossa

Internal criticism, aka positive criticism, is the attempt

of the researcher to restore the meaning of the text. This is

the phase of hermeneutics in which the researcher engages

with the meaning of the text rather than the external

elements of the document. Here, more than before, domain

specific knowledge of context is essential.

In this stage of investigation the researcher and

exegete engage in positive criticism, which attempts to

restore the meaning of statements, and negative criticism,

which places doubt on what external and positive criticism

have established as reasonable findings. Here the

researcher and exegete combat both aesogesis and

untrustworthiness.

In positive criticism the historian and exegete assess

the literal meaning of the text and the real meaning of

statements. Literal meanings are the immediate meanings

of a document and often fool the immature reader. Often

poetry is written in a way that the meaning is hidden behind

a style of language, i.e., literary devices, which necessitate

an understanding of such language and what rules are

applied to identify and interpret them. For example, Psalm 1

is full of metaphors and simile and unless the reader

understands such devices there is no way one can

understand the meaning of the passage; however, before

venturing into the discovery of a meaning behind the literal

text, the reader must deal with the text as is by asking “what

does the statement say?” and then ask “what’s the point the

author is making in the statement?” In the case of Psalm 1,

the reader will soon discover that there is more to the text

than a simple aim of beautifying ones relationship with God

by using literary devices – there is power of meaning in the

metaphors and similes used by the author and a reason for

the author to select such metaphors. I am talking here of

authorial intent, which in itself raises controversy as to

whether such can really be known in the absence of the

original author (Ryken). The verdict pronounced by some

theologians such as the Biblical theology of missions’

advocates is that the theme of missio Dei is the standard

against which to judge the truthfulness of meaning and

legitimacy of purpose of a scriptural text.

There is another problem of language that pertains to

the fact that some texts, i.e., Shakespeare, the KJV Bible,

were not written in today’s language. This also requires a

contextual understanding of the style in which the text was

written before the attribution of meaning. For example, in

the archaic English of the KJV the word gay means happy

while in today’s society such is a reference to sexual

orientation.

While positive criticism simply attempts to ascertain

what the text means by analyzing its statements within a

context, i.e., literary, historical, geographical, etc.; in

negative criticism, the historian conducts (a) tests of

competence; (b) gossip, humor and slander; (b) myths,

legends and traditions; (c) tests of truthfulness; and, (d)

discredit statements. According to Hockett, in the latter, the

critic engages in ascertaining what opportunity the maker of

the statement had to know the facts, i.e., eyewitness versus

the conditions under which the witness observed the event

and how the witness relates to other witness accounts, the

position of observation, etc.. Essentially, this is the starting

point of ascertaining the meaning of the text. Other sources

that must equally be checked against their background are

newspaper claims which may be tinted with issues of

affiliation and patronage. The claims within the newspapers

articles of slavery times should be scrutinized against the

times and the civilization in vogue. For example, I would

doubt any news article written by the mainstream

newspapers during slavery times reporting on an issue of

rape of a white woman by a black male, but if the Chicago

Times in 2002 reported the same I would be more inclined

to believe although not without suspicion since racism and

stereotypes are still evident in today’s society.

The other elements to be doubted are oral testimony in

the form of gossip, rumor, slander, myth, legends, and

traditions, because they often result from various motives

that might be questionable. The integrity of the source is of

utmost importance. However, Hockett stands firmly on

positivistic grounds and diminishes the value of orate

traditions. Glick supports the opposite of what Hockett

propagates, and today there is more evidence that even

within orate traditions there are experts and novices and

such experts merit greater reliance (Goldman).

Hockett discusses tests of truthfulness that might aid

the researcher to deal with the question of whether the

integrity of the source always goes hand-in-hand with the

statements being true. The advice is to inquire whether the

source had any personal interest, and the affiliation of the

source to race, party, sect, society, etc. In the example of

the rape during slavery, one is more likely to doubt a

statement made in those days by the newspaper because

the journalists were likely to be Caucasians and a part of

the elite. The intentions of the source are coupled with bias,

which is an enemy of impartial truth, if such [impartial truth]

ever exists. To deal with bias one has to be aware of the

different perspectives of the writers as they have been, or

are, influenced by factors of various kinds. For instance,

Hockett’s bias is evident as he rests on one methodology,

i.e., positivism, to ascertain facts. His advice to refrain from

investigating miracles when such are against the laws of

nature is clear evidence that historians have strong biases

too.

External Criticism: A Brief Reflection

Copyright © 2002 José Cossa

External criticism, which is also known as lower

criticism, is a tool used by historians and exegetes to

determine the validity of a document, particularly a

document with some sort of historical significance. It is the

first of two stages of inquiry for it is followed by internal

criticism. It ventures towards inquiry regarding (a)

authorship; (b) originality and accuracy of copy; and (c) if

errors are found it helps assess the nature of errors found,

i.e., if they are scribal errors or other kinds of errors.

In dating text, historians and exegetes assess if there

are any inconsistencies in the source (text) rather than

assume immediate knowledge of when the text was written,

i.e., is the source what it claims to be? Does anything nullify

the claim of the source? In the process of recovering, to the

very best of his ability, the original text of scripture or of a

document, the historian must resolve the inconsistencies

found within the text or source and explain them.

Some of the dates found in the books of the Bible are

conflicting with the actual times of historical events that are

known to have happened in the time claimed in the books

of the Bible and the names associated with them, i.e.,

Isaiah. Biblical lower criticism has preoccupied itself with

explaining these errors or inconsistencies for as long as the

external criticism technique has been in existence. With the

advent of this method of criticism and others other forms of

textual criticism, i.e., internal criticism, there has been

conflict over whether the technique is moral for it challenges

both the belief of inerrancy and infallibility of scripture;

however, with general historical documents the technique is

less of an issue. For example, Max Anders claims that the

Bible as originally written was without errors and that any

apparent error or contradiction can be explained – for him,

one must separate fact from details that seem

contradictory. He states that if he tells his wife that he is

going to the post office and then on the way back he tells

her that he picked a screwdriver at the hardware store, he

would have not lied by omitting the trip to the hardware

store. This, he claims, is one of the many incidents

classified by critics as errors and contradictions in

Scriptures.

Some biblical scholars agree that there are apparent

contradictions, but the facts in the Bible remain true and

untouched by the seeming contradiction – One example of

this school can be seen in the field of Biblical theology of

missions (e.g., John York, my former professor of this

subject), where some schools claim that there is one

underlying theme in the Bible, i.e., missio Dei [lat. mission

of God], from which drives the entire message and purpose

of the writings and is above all the seeming contradictions

found in the minute details. According to this school, God’s

mission of redemption of mankind is a theme that is left

undisturbed by errors and seeming contradictions of

manuscripts, and runs from Genesis to Revelations. This

aspect of one theme will be discussed also within the

context of internal criticism. I present this argument here to

explain that one’s understanding of infallibility of the Bible

can be a factor in determining internal evidence because

some schools, not necessarily that advocated by York,

have gone to extremes of not wanting to temper with the

text of Scripture either because of its sacredness or

because there is no need to do so since the purpose of

scripture is to present a particular message and the details

do not matter.

In spite of the contradictions between various biblical

scholars and historians, both exegetes and historians have

benefited from the technique of lower criticism because

they have managed to make better sense out of conflicting

passages within the literature that they analyze.

In determining authorship, the tool of external criticism

helps the researcher and exegete to assess the author’s

name, affiliation, i.e., religious group, political party,

ethnicity, etc. In this phase the researcher attempts to

determine authorship by (a) using internal evidence about

the author; (b) using supplementary data from other

material related to the descriptions in the text such as

history, geography, etc.; (c) assessing the tone of

document, (d) identifying patterns or streams that help

establish connection to original author when dealing with

anonymous writings; (e) identifying clues of authorship; (f)

assessing the presence of second or third party speech

writers, ghostwriters, and plagiarists.

In determining the evidence of date the researcher

also looks at the language used, the sequence and

relationship of events

You might also like

- Biblicalliterarycriticism 151023203316 Lva1 App6892Document5 pagesBiblicalliterarycriticism 151023203316 Lva1 App6892esreys7No ratings yet

- Validity in the Identification and Interpretation of Literary Allusions in the Hebrew BibleFrom EverandValidity in the Identification and Interpretation of Literary Allusions in the Hebrew BibleNo ratings yet

- LiteratureDocument10 pagesLiteratureMarimar PungcolNo ratings yet

- HST 3013 - Rumusan ArtikelDocument7 pagesHST 3013 - Rumusan ArtikelFiddaudin ArsatNo ratings yet

- Advanced HermeneuticsDocument10 pagesAdvanced Hermeneuticsbingyamiracle100% (1)

- 17 DDocument9 pages17 DAlex LottiNo ratings yet

- Historical Critical MethodsDocument12 pagesHistorical Critical MethodsDavid Lalnunthara DarlongNo ratings yet

- New Testament Interpretation Through Rhetorical CriticismFrom EverandNew Testament Interpretation Through Rhetorical CriticismNo ratings yet

- Internal and External CriticismDocument2 pagesInternal and External Criticismgemma carandangNo ratings yet

- Esponse: W. Malcolm Clark Butler UniversityDocument2 pagesEsponse: W. Malcolm Clark Butler UniversitydavidNo ratings yet

- Interview With David CarrDocument7 pagesInterview With David CarrJM164No ratings yet

- Week 4 Lesson D 3 Worlds of The Bible-1Document16 pagesWeek 4 Lesson D 3 Worlds of The Bible-1PrincessNo ratings yet

- Are There Two Contradicting Creation Accounts in GenesisDocument23 pagesAre There Two Contradicting Creation Accounts in GenesisspaghettipaulNo ratings yet

- Truth or Meaning Ricoeur Versus FreiDocument25 pagesTruth or Meaning Ricoeur Versus FreiLuís PereiraNo ratings yet

- Ancient Literature and Philosophy of Religion: Comparative Research in the West’s Most Sacred TextsFrom EverandAncient Literature and Philosophy of Religion: Comparative Research in the West’s Most Sacred TextsNo ratings yet

- Quotes Allusions and Echoes Some Thoughts PDFDocument8 pagesQuotes Allusions and Echoes Some Thoughts PDFspaghettipaulNo ratings yet

- Historical Critical MethodDocument11 pagesHistorical Critical MethodjeevanNo ratings yet

- John - New 3Document6 pagesJohn - New 3Papa GiorgioNo ratings yet

- External and Internal CriticismDocument4 pagesExternal and Internal Criticismjohn marlo andradeNo ratings yet

- Importance of Historical CriticismDocument3 pagesImportance of Historical CriticismBRIANNE JOSUA CALUNGSODNo ratings yet

- Sunnom NUANCE EditDocument14 pagesSunnom NUANCE EditDomi Sunnom MitchelNo ratings yet

- Summary - The Art of Biblical History (Intro & Ch. 1)Document6 pagesSummary - The Art of Biblical History (Intro & Ch. 1)jwh129150% (2)

- In Defense of Biblicism: Reflections on Sola ScripturaDocument19 pagesIn Defense of Biblicism: Reflections on Sola ScripturaLiem Sien LiongNo ratings yet

- (VigChr Supp 092) Joel Stevens Allen - The Despoliation of Egypt in Pre-Rabbinic Rabbinic and Patristic TraditionsDocument313 pages(VigChr Supp 092) Joel Stevens Allen - The Despoliation of Egypt in Pre-Rabbinic Rabbinic and Patristic TraditionsNovi Testamenti Filius100% (3)

- How To Read A Primary Source: C C C C C C C C C C CDocument4 pagesHow To Read A Primary Source: C C C C C C C C C C CzkottNo ratings yet

- Ironic Representation, Authorial Voice, and Meaning in QoheletDocument32 pagesIronic Representation, Authorial Voice, and Meaning in QoheletalfalfalfNo ratings yet

- Exegetical Fallacies: Common Interpretive Mistakes Every Student Must AvoidDocument14 pagesExegetical Fallacies: Common Interpretive Mistakes Every Student Must AvoidErwin Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- How Jews and Christians Interpret Their Sacred Texts: A Study in TransvaluationFrom EverandHow Jews and Christians Interpret Their Sacred Texts: A Study in TransvaluationNo ratings yet

- Rogers - Defending BoethiusDocument17 pagesRogers - Defending BoethiusMichael WiitalaNo ratings yet

- Battle of the Gods; Comparing the Literature of the Judeo-Christian Deity With Polytheistic Works of the Ancient Near East: Debates of the Reliability of the Christian Bible, #2From EverandBattle of the Gods; Comparing the Literature of the Judeo-Christian Deity With Polytheistic Works of the Ancient Near East: Debates of the Reliability of the Christian Bible, #2No ratings yet

- Study Edition,: Book ReviewsDocument2 pagesStudy Edition,: Book Reviewscatalin barascuNo ratings yet

- Crisis in Jerusalem? Narrative Criticism in New Testament StudiesDocument18 pagesCrisis in Jerusalem? Narrative Criticism in New Testament StudiesLazar PavlovicNo ratings yet

- Pagan-Christian Debates over Interpreting Ancient TextsDocument22 pagesPagan-Christian Debates over Interpreting Ancient TextsEvangelosNo ratings yet

- Reading The Bible From The Margins by Miguel de La Torre (2003)Document9 pagesReading The Bible From The Margins by Miguel de La Torre (2003)tordet130% (1)

- Issues in Hermeneutical FoundationsDocument133 pagesIssues in Hermeneutical FoundationsCalvinKnox100% (1)

- Ancient Near Eastern Thought and The Old Testament Summary Final ValentiDocument27 pagesAncient Near Eastern Thought and The Old Testament Summary Final ValentiLionel Jaque SmithNo ratings yet

- Exegetical FallaciesDocument11 pagesExegetical Fallaciesaaronrice89No ratings yet

- Theological Interpretation of ScriptureDocument21 pagesTheological Interpretation of ScriptureTony Lee100% (1)

- THE TEXT AND THE MESSAGEDocument4 pagesTHE TEXT AND THE MESSAGEChinku RaiNo ratings yet

- Problems with Preterism: An Eschatology Built upon Exegetical Fallacies, Mistranslations, and the Misunderstanding of a GenreFrom EverandProblems with Preterism: An Eschatology Built upon Exegetical Fallacies, Mistranslations, and the Misunderstanding of a GenreNo ratings yet

- Exploring American Histories Volume 2 A Survey With Sources 3rd Edition Ebook PDFDocument48 pagesExploring American Histories Volume 2 A Survey With Sources 3rd Edition Ebook PDFmichelle.harper966100% (30)

- Bible Ethics Tensions and ComplexityDocument10 pagesBible Ethics Tensions and ComplexityZdravko JovanovicNo ratings yet

- Bible Literalism and Constitutional OriginalismDocument66 pagesBible Literalism and Constitutional OriginalismBrian ShoafNo ratings yet

- The Book of Esther and Ancient StorytellingDocument13 pagesThe Book of Esther and Ancient Storytellinggalilej12259100% (2)

- Week 4 6Document10 pagesWeek 4 6Ma Clarissa AlarcaNo ratings yet

- An Incarnational Model of ScriptureDocument14 pagesAn Incarnational Model of ScriptureStephen ScheidellNo ratings yet

- ENGLISH 119 - DraftDocument5 pagesENGLISH 119 - DraftBrod LenamingNo ratings yet

- Biblical Literalism and Varieties of CreationismDocument7 pagesBiblical Literalism and Varieties of CreationismKross Lnza KhiangteNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Book of Joel1Document14 pagesIntroduction To The Book of Joel1teddy chongoNo ratings yet

- Speech Act Theory and Biblical InerrancyDocument10 pagesSpeech Act Theory and Biblical InerrancyMas WahyudiNo ratings yet

- Importance of historical criticismDocument1 pageImportance of historical criticismDharell Dimla PitogoNo ratings yet

- Winter 2009Document3 pagesWinter 2009johnmcgaryNo ratings yet

- 1 Peter (Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament)From Everand1 Peter (Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- Liberalism Versus Postliberalism - The Great Divide in Twentieth-Century Theology (PDFDrive)Document408 pagesLiberalism Versus Postliberalism - The Great Divide in Twentieth-Century Theology (PDFDrive)Fadi Abdel NourNo ratings yet

- Historical-Critical MethodDocument4 pagesHistorical-Critical MethodLijo DevadhasNo ratings yet

- Bart Interrupted by DR Ben Witherington IIIDocument31 pagesBart Interrupted by DR Ben Witherington IIIDixonDANo ratings yet

- Adobe Photoshop Q&ADocument2 pagesAdobe Photoshop Q&AmonojdekaNo ratings yet

- 2013 Solved Paper Computer SkillDocument4 pages2013 Solved Paper Computer SkillmonojdekaNo ratings yet

- CPP ProgrammingDocument124 pagesCPP ProgrammingmonojdekaNo ratings yet

- 5Document3 pages5monojdekaNo ratings yet

- Assam DanceDocument1 pageAssam DancemonojdekaNo ratings yet

- Photoshop Question With AnswerDocument15 pagesPhotoshop Question With AnswermonojdekaNo ratings yet

- Fort RanDocument22 pagesFort RanmonojdekaNo ratings yet

- Fish Species of AssamDocument4 pagesFish Species of Assammonojdeka75% (4)

- Chandrasekhar AzadDocument4 pagesChandrasekhar AzadmonojdekaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Literature of Europe: Lesson 1Document32 pagesIntroduction To Literature of Europe: Lesson 1Lisha GersavaNo ratings yet

- Tapestry Poetry by Presto Plans PDFDocument5 pagesTapestry Poetry by Presto Plans PDFThin HtetNo ratings yet

- Upon Westminster BridgeDocument5 pagesUpon Westminster BridgeNandana Ann GeorgeNo ratings yet

- 2nd Book Marty's JobDocument12 pages2nd Book Marty's JobAMMIVA CENTERNo ratings yet

- Baylon Sunset-PaperDocument4 pagesBaylon Sunset-PaperRhyxel dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Chapter X - Preactivity - Literature in Caraga RegionDocument2 pagesChapter X - Preactivity - Literature in Caraga RegionTimon Carandang100% (3)

- Understanding William H. Gass (Understanding Contemporary American Literature) (H. L. Hix)Document204 pagesUnderstanding William H. Gass (Understanding Contemporary American Literature) (H. L. Hix)Gabriel de Camargo ColenciNo ratings yet

- Opposites 87608Document2 pagesOpposites 87608Emilia Mihaela CostescuNo ratings yet

- InfernoDocument2 pagesInfernoMominaAbrarNo ratings yet

- Problems of Lexicology and LexicographyDocument9 pagesProblems of Lexicology and LexicographyIsianya JoelNo ratings yet

- The Valediction of Moses A Proto BiblicaDocument217 pagesThe Valediction of Moses A Proto BiblicaJonathan Heli Gonzalez GallegoNo ratings yet

- Four Different Types of Writing StylesDocument9 pagesFour Different Types of Writing StylesEmmeline BlairNo ratings yet

- Conflicting Perspectives in PoetryDocument2 pagesConflicting Perspectives in Poetrydiamondxizta100% (1)

- UntitledDocument12 pagesUntitledtalib ANo ratings yet

- The Wizard of Oz Book Review (39 charactersDocument7 pagesThe Wizard of Oz Book Review (39 charactersMuhammad ArslanNo ratings yet

- Chris Tse: For The New Zealand Poet of The Same Name, See Chris Tse (New Zealand Writer)Document3 pagesChris Tse: For The New Zealand Poet of The Same Name, See Chris Tse (New Zealand Writer)Emerson CharlesNo ratings yet

- PPT-1-Introduction To Australian Literature PDFDocument2 pagesPPT-1-Introduction To Australian Literature PDFRitu Mishra100% (1)

- Oliver Twist Chapter SummaryDocument14 pagesOliver Twist Chapter SummaryVirginia Gómez RojasNo ratings yet

- African Culture and Thai TraditionsDocument98 pagesAfrican Culture and Thai TraditionsJeraldine Repollo100% (1)

- Lesson 2 Texts and Authors MaterialDocument52 pagesLesson 2 Texts and Authors MaterialRommel LegaspiNo ratings yet

- LectureDocument6 pagesLectureEnseignante De FrançaisNo ratings yet

- Character in The Gospel of John PDFDocument19 pagesCharacter in The Gospel of John PDFiblancoeNo ratings yet

- LIKE A JOKE THAT SEEMS TRUE (Wabe)Document12 pagesLIKE A JOKE THAT SEEMS TRUE (Wabe)Gwynne WabeNo ratings yet

- Direction: Read The Poem Carefully. Answer The Guide Questions Provided. Please Take Pictures On Your Output Then Send It Thru May MessengerDocument6 pagesDirection: Read The Poem Carefully. Answer The Guide Questions Provided. Please Take Pictures On Your Output Then Send It Thru May MessengerJohn JohnnyNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Mla StyleDocument6 pagesLiterature Review Mla Styleea98skah100% (1)

- Innovative Techniques in Writing PoetryDocument15 pagesInnovative Techniques in Writing PoetryMae Joenette C. Remeticado100% (1)

- From Ibsen's WorkshopDocument546 pagesFrom Ibsen's WorkshopCesar MéndezNo ratings yet

- Great Expectations A Manifestation of Gothicism and RomanticismDocument6 pagesGreat Expectations A Manifestation of Gothicism and RomanticismEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- EUROPEAN LITERATURE HISTORYDocument3 pagesEUROPEAN LITERATURE HISTORYcesty100% (1)

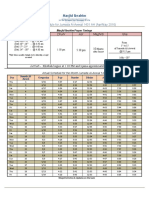

- Jumada Al-Awwal 1431 AH Prayer ScheduleDocument2 pagesJumada Al-Awwal 1431 AH Prayer SchedulemasjidibrahimNo ratings yet