Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Krasnikov2008 The Relative Impact

Uploaded by

Jean KarmelOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Krasnikov2008 The Relative Impact

Uploaded by

Jean KarmelCopyright:

Available Formats

Alexander Krasnikov & Satish Jayachandran

The Relative Impact of Marketing,

Research-and-Development, and

Operations Capabilities on Firm

Performance

The impact of the marketing function on firm performance has been the focus of much recent research in marketing.

Thus, the effect of marketing capability on firm performance, compared with that of other capabilities, such as

research and development and operations, is an issue of importance to managers. To examine this issue and

generate empirical generalizations, the authors conduct a meta-analysis of the firm capability–performance

relationship using a mixed-effects model. The results show that, in general, marketing capability has a stronger

impact on firm performance than research-and-development and operations capabilities. The results provide

guidelines for managers and generate directions for further research.

Keywords: marketing capability, research-and-development capability, operations capability, meta-analysis, mixed-

effects model, firm performance, capability–performance relationship

apabilities are complex bundles of skills and knowl- ings gains generated through cost cutting and efficient

C edge embedded in organizational processes (Helfat

and Peteraf 2003). They are critical sources of sus-

tainable competitive advantage used by firms to leverage

operations are less sustainable and, thus, less valuable than

earnings gains from a revenue increase (Zuckerman and

Hudson 2007). This comment implies that the payoff from

their assets and achieve superior performance. Capabilities emphasizing capabilities that result in lower costs and more

serve as the “glue” that binds different resources together efficient operations could be different from that obtainable

and enables them to be deployed to maximum advantage by focusing on capabilities that result in revenue growth.

(Day 1994, p. 38). The role of marketing capability in dri- Therefore, research providing empirical generalizations for

ving superior firm performance has been of significant the relationship of different types of capabilities to perfor-

interest to marketing scholars (e.g., Capron and Hulland mance and an examination of how they vary would benefit

1999; Day 1994; Grewal and Tansuhaj 2001; Vorhies and managers and academics.

Morgan 2005). However, empirical research that directly Despite a significant volume of research on the relation-

examines the impact of a firm’s marketing capability on ship of capabilities to performance, the findings regarding

performance, compared with the impact of capabilities in this relationship often vary substantially in terms of magni-

other functional areas, such as research and development tude. The predominant view in prior research is that capa-

(R&D) and operations, is scarce. This leaves unresolved the bilities are positively associated with performance (Day

issue of whether marketing capability has a greater or lesser 1994). Nevertheless, several studies report that capabilities

influence on firm performance than other capabilities. can turn into core rigidities and might even have a negative

The relative importance of marketing capability in dri- influence on some aspects of firm performance (e.g., Haas

ving performance is a significant issue in light of the con- and Hansen 2005; Leonard-Barton 1992). Therefore,

cerns expressed about the role of marketing in building firm empirical generalizations from previous research would

value (Srivastava, Shervani, and Fahey 1998, 1999). In a also help assess the overall impact of firm capabilities on

recent story about the stock price of the retail firm performance and highlight study characteristics that may

RadioShack, the Wall Street Journal commented that earn- cause variation in the relationship.

To address these objectives, we conduct a meta-analytic

Alexander Krasnikov is Assistant Professor of Marketing, Department of assessment of the capability–performance relationship. In

Marketing, School of Business, George Washington University (e-mail: doing so, we focus on three types of capabilities: marketing,

avkrasn@gwu.edu). At the time of writing, he was a postdoctoral research R&D, and operations. Marketing capability represents a

fellow, Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University. Satish firm’s ability to understand and forecast customer needs

Jayachandran is Associate Professor of Marketing and Moore Research better than its competitors and to effectively link its offer-

Fellow, Department of Marketing, Moore School of Business, University of ings to customers (market sensing and customer-linking

South Carolina (e-mail: satish@moore.sc.edu). The authors thank Kelly

Hewett, Robert Ployhart, and Chris White for their comments and assis-

capabilities; Day 1994). Research-and-development capa-

tance in developing this article. bility is a firm’s competency in developing and applying

different technologies to produce effective new products

© 2008, American Marketing Association Journal of Marketing

ISSN: 0022-2429 (print), 1547-7185 (electronic) 1 Vol. 72 (July 2008), 1–11

and services. Operations capability is the skills and knowl- opment of the database for the meta-analysis. Following

edge that enable a firm to be efficient and flexible producers this, we provide the analysis and present the results. Finally,

or service providers that use resources as fully as possible. we discuss the implications and suggest future research

We recognize that capabilities can be characterized in directions.

other ways, such as classifications that employ a more

micro approach (e.g., customer-relating capability; Day

2000). Our interest in marketing, R&D, and operations Capabilities and Performance

capabilities is shaped by two issues, one fundamental and The resource-based view of the firm argues that resources

the other practical. The fundamental issue is that marketing, that differ in value, rarity, imitability, and sustainability are

R&D, and operations are core organizational functions at the root of competitive advantage (Barney 1991; Penrose

involved in developing and implementing a strategy that 1959; Wernerfelt 1984). The resource-based view has had

results in sustained advantage. For example, Treacy and an influence on the dialogue in the marketing strategy lit-

Wiersema (1993) argue that superior customer value can be erature by helping researchers articulate the drivers of

delivered through operational excellence, customer inti- competitive advantage (e.g., Bharadwaj, Varadarajan, and

macy, and product leadership. These strategies are evidently Fahy 1993; Capron and Hulland 1999; Hunt and Morgan

related to operations capability, marketing capability, and 1995). The capabilities perspective suggests that it is the

R&D capability, respectively. The practical issue is that in a capabilities, more than the resources, that enable the

meta-analysis, we are limited by the availability of enough deployment and leveraging of resources that help some

studies that examine a particular relationship. Focusing on firms perform better than others (Grant 1996; Teece,

marketing, R&D, and operations capabilities enables us to Pisano, and Shuen 1997). Capabilities enable a firm to per-

overcome the sparse data problem caused by the lack of form value-creating tasks effectively, and they reside in

availability of a sufficient number of prior studies that organizational processes and routines that are difficult to

examine the relationship of a particular capability to perfor- replicate. Capabilities are deeply rooted in these processes

mance. In effect, we do not claim that our categorization and therefore are embedded within organizations in the

of firm capabilities in the context of this meta-analysis is complex mesh of interconnected actions that follow mana-

exhaustive. Rather, the study summarizes the effect of the gerial decisions over time. In effect, capability embedded-

most widely examined capabilities on performance. ness, or its incorporation into the surrounding context, cre-

Overall, this study seeks answers to the following ates barriers to imitation, enabling firms to enjoy

questions: sustainable advantage over their rivals (Grewal and Slote-

graaf 2007). In addition, Danneels (2002) proposes that

•What is the mean impact of capability on performance?

existing capabilities may serve as leverage points for the

•Does the impact on performance vary for marketing, R&D,

development of new ones that help a firm sustain its perfor-

and operations capabilities?

mance. Overall, capabilities are key determinants of a firm’s

•What other study characteristics moderate the overall rela-

tionship between capabilities and performance? competitive advantage and, thus, its performance (Day

1994). In general, the weight of arguments in prior research

As a preview, the empirical generalizations we derive supports a positive association between capability and

from prior research show that capabilities in general and performance.

marketing, operations, and R&D capabilities in particular Capabilities have been demarcated according to their

are positively associated with performance. Using hierar- different functional areas. In this article, we limit our atten-

chical linear modeling (HLM) and controlling for the effect tion to marketing, R&D, and operations capabilities and

of other study characteristics, we demonstrate that market- their impact on performance. Fundamentally, marketing is

ing capability has a stronger influence on performance than the function that is responsible for meeting customer needs.

R&D capability and operations capability. This is an impor- Therefore, marketing capability is the organizational com-

tant finding in the context of the discussion about the role petence that supports market sensing and customer linking.

of marketing in firm value creation (e.g., Rust et al. 2004; As such, marketing capability spans processes that are

Srivastava, Shervani, and Fahey 1998, 1999). For example, established within organizations to decipher the trajectory

industry surveys often provide evidence that senior manage- of customer needs through effective information acquisi-

ment is unsure of the value of the marketing function and tion, management, and use. In addition, marketing capabil-

therefore might be less inclined to invest in developing mar- ity involves the processes that enable a firm to build sus-

keting capabilities (e.g., O’Halloran 2004). The results from tainable relationships with customers (Day 1994).

the current research support Srivastava, Shervani, and Research-and-development capability refers to the pro-

Fahey’s (1998) argument about the importance of marketing cesses that enable firms to invent new technology and con-

assets for firm performance and highlight the potential folly vert existing technology to develop new products and ser-

of not focusing on investments that build marketing capabil- vices. Therefore, R&D capability depends on the routines

ity. Overall, by summarizing the results from a large body that help a firm develop new technical knowledge, combine

of research, we provide findings that advance the dialogue it with existing technology, and design superior products

on the role of marketing in firms. and services. Operations capability is focused on perform-

We organize the article as follows: We begin with a dis- ing organizational activities efficiently and flexibly with a

cussion of the theoretical issues related to capabilities minimum wastage of resources. Therefore, these capabili-

research and offer hypotheses. Then, we explain the devel- ties are related to efficient manufacturing and logistics.

2 / Journal of Marketing, July 2008

Overall, operations capability has been described as focus- contexts and methods, salient study design factors can be

ing on efficient delivery of quality products and services, coded, and their moderating effect on the capability–

cost, and flexibility (Tan et al. 2004).1 performance relationship can be tested. Next, we discuss

As we noted previously, capabilities are often not the various factors that cause variation in the

explicitly visible. As such, the measurement of capabilities capability–performance relationship.

has frequently been based on secondary proxy measures

that are considered their valid outward manifestations. For

example, marketing capability has been assessed using Impact of Different Types of

measures such as market research and advertising expendi- Capabilities and Other Study

tures (e.g., Dutta, Narasimhan, and Rajiv 1999). Many other Characteristics

studies have employed primary measures by developing The framework shown in Figure 1 outlines the potential

scales to quantify facets of marketing capability (e.g., Day impact of different types of factors on the capability–

2000; Jayachandran, Hewett, and Kaufman 2004). The performance relationship. One primary factor that causes

measurement of R&D capability has also been approached

variance in the capability–performance relationship is the

in a manner similar to that used in capturing marketing

type of capability—that is, marketing, R&D, or operations.

capability. The most frequently used measure of R&D capa-

In addition, we examine several other study characteristics

bility is based on R&D expenditure, which is often stan-

as potential moderators of the capability–performance

dardized relative to industry expenditures and expressed as

relationship.

R&D intensity (e.g., Dutta, Narasimhan, and Rajiv 1999).

Rating scales have also been used to capture R&D capabil-

Impact of Different Types of Capabilities

ity in studies in which primary data are employed (e.g.,

Song et al. 2005). Operations capability has been measured The impact of capabilities on performance is governed by

through scales of its various dimensions, such as flexibility, two characteristics of the knowledge that drives them: the

cost efficiency, and logistics (e.g., Tan et al. 2004). In addi- difficulty that rivals face in copying them (imperfect

tion, studies have employed primary measures of produc- imitability) and the difficulty they have in obtaining them

tion competence to assess operations capability (Vickery, from the market (imperfect mobility). Marketing, R&D, and

Dröge, and Markland 1997). operations capabilities may differ with respect to the

The performance measures to which capabilities are imitability and mobility of the knowledge that supports

related distinguish between two types of outcomes: market them. Thus, and as we discuss in detail next, the impact of

performance and efficiency performance (e.g., Dutta, these different capabilities on performance could vary.

Narasimhan, and Rajiv 1999; Eisenhardt and Martin 2000). Marketing capability is based on market knowledge

Market performance refers to measures such as market about customer needs and past experience in forecasting

share, profitability, and sales, whereas efficiency perfor- and responding to these needs (Day 1994). Market knowl-

mance refers to measures such as cost reduction, lead-time edge usually develops over time through learning and

reduction, and time to market. experimentation. Simonin (1999) notes that a substantial

In summary, prior research has examined the relation- part of market knowledge is difficult to codify because of

ship between capabilities and performance using various its socially complex nature, implying that market knowl-

approaches. The studies have used both primary and sec- edge is distributed across multiple groups and people. The

ondary data. There is some variation in the measures that assumptions of experiential learning and social complexity

are employed to quantify different capabilities, though the of market knowledge suggest that, to a large degree, mar-

conceptual approaches to defining and articulating capabili- keting capability is based on knowledge that is tacitly held

ties are largely consistent. The variance in how the studies and difficult for rivals to copy (imperfect imitability). Even

are designed and how the constructs are measured is attrib- when market knowledge is codified and can be transmitted,

utable to the broad theoretical sweep of the core construct, as in customer satisfaction measurement systems, the

namely, firm capability. Because conceptually broad phe- knowledge is closely held, leading to imperfect mobility

nomena need to be studied over a diverse set of contexts, it (difficulty in obtaining this capability through a market sys-

is considered appropriate to include studies that vary in sit- tem). Overall, marketing capability is likely to be immune

uations and procedures when summarizing such research in to competitive imitation and acquisition because of the dis-

a meta-analysis (Hunter and Schmidt 1990). Indeed, a tributed, tacit, and private nature of the underlying

meta-analysis of theoretically broad constructs that includes knowledge.

studies that vary in context and methods would help assess The knowledge and processes that underpin R&D capa-

construct validity and the validity of an effect through trian- bility and drive innovations are likely to be more codified

gulation. Furthermore, a relationship that is supported under than the knowledge that supports marketing capability.

various situations lends credence to its robustness (Hall et Technological developments are typically manifested in

al. 1993). In addition, to account for the variance in study inventions that are patented. In the patenting process, the

inventor must disclose critical information about the tech-

nology. Thus, even if the patent provides the inventor firm

1Note that “quality,” as referred to in the context of operations

with protection from copying, the codified knowledge dis-

capability, is that of low-defect manufacturing quality and not

consumer-perceived quality, the more widely accepted notion of

closed enables a competitor to build on or around the origi-

the term in the marketing literature. nal invention (Anand and Khanna 2000; Levin et al. 1987).

Marketing, R&D, and Operations Capabilities / 3

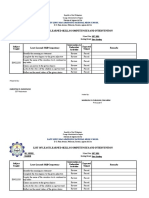

FIGURE 1

Theoretical Framework for the Meta-Analysis

Factors Affecting the Capability–Performance

Relationship

Capability Type (H1, H2)

•Marketing

•R&D

•Operations

Other Factors

•Market versus efficiency performance

•Large versus small firms

•Subjective versus objective data

•Business-to-business versus business-to-consumer

•Manufacturing versus service business

•U.S. versus non-U.S. firms

•Strategic business unit versus firm level

•Multiple versus single industry

Capability Performance

In comparison, there is no overt pressure to codify the In effect, R&D capability and operations capability are

knowledge that supports marketing capability and to dis- relatively more susceptible to imitation and are relatively

close it in the public domain. Further adding to the mobility more mobile than marketing capability. This renders

of R&D capability is the idea that to reduce R&D competi- competitive advantage based on these capabilities more

tion that might otherwise make innovation too costly, firms prone to competitive interference than advantage based on

might even license their discoveries to rivals (Anand and marketing capability. However, note that though we argue

Khanna 2000). Overall, this argument suggests that R&D for the relatively stronger impact of marketing capability on

knowledge and processes are codified and shared to a performance, we are not decrying the importance of R&D

greater degree than the more tacitly held marketing knowl- capability and operations capability. There may be specific

edge and processes. Therefore, in general, R&D capability industries in which R&D capability and operations capabil-

is likely to be more imitable and mobile than marketing ity are more important than marketing capability. However,

capability. our hypotheses are based on general findings and not

Operations capability is frequently based on processes industry-specific or firm-specific findings. Our primary

that have been benchmarked and codified. For example, contention is that given the nature of the knowledge that

many firms have pursued total quality management and drives these capabilities, marketing capability typically

international standards organization programs to enhance leads to stronger performance than R&D capability and

quality and efficiency. Similarly, many firms have imple- operations capability.

mented business process reengineering to redesign business

H1: The capability–performance relationship is stronger for

systems and work flow and to employ information technol- marketing capability than for R&D capability.

ogy to enhance efficiency. The activities to be adopted by H2: The capability–performance relationship is stronger for

organizations that followed total quality management and marketing capability than for operations capability.

international standards organization programs are codified

and certified, as well as aided by consultants. For business Other Study Characteristics That Influence the

process reengineering, companies also take advantage of the Capability–Performance Relationship

expertise offered by consultants. Thus, some of the seminal

efforts that drove operations capability over the past two To examine H1 and H2 in a meta-analysis, we need to

decades were not necessarily based on firm-specific skills account for other study characteristics that might also influ-

but rather on skills that were available to all firms from the ence the overall capability–performance relationship. Next,

external market. Pursuing capabilities based on codified we discuss the study characteristics that might affect the

processes may not afford an organization the ability to capability–performance relationship.

achieve competitive advantage. For example, Carr (2003) Performance type. As we noted previously, prior

argues that the core functions of information technology, research has examined the role of capabilities in terms of

such as data processing and storage, are widely available efficiency in integrating and reconfiguring resources (e.g.,

and largely affordable and therefore do not provide an Dutta, Narasimhan, and Rajiv 1999; Eisenhardt and Martin

operations capability that leads to sustained advantage. 2000) and their impact on market outcomes (e.g., Vorhies

4 / Journal of Marketing, July 2008

and Morgan 2005). Therefore, the outcome of capabilities is firms in multiple industries might also influence the

assessed using different types of metrics related to effi- capability–performance relationship. Capabilities required

ciency performance and market performance. As such, in for success in different industries vary. When data are col-

coding the effect of capability on performance, we distin- lected within a single industry, it is likely that the capability

guish between efficiency performance and market associated with success in that specific industry can be mea-

performance. sured in a fine-grained manner. In contrast, when data are

Large versus small firms. The link between organiza- collected from firms that operate in different industries, the

tional capabilities and performance may vary for firms measurement of capability might need to be at a more

operating on different scales. Firm capabilities are deeply aggregate level, thus obscuring the relationship of capabil-

embedded in organizational processes and routines (Day ity to performance. As such, the capability–performance

1994). Larger firms have more idiosyncrasies in which mul- relationship could be stronger in studies that focus on one

tiple organizational routines coexist. Furthermore, larger industry than for studies with multi-industry data.

organizations are characterized by more complex routines

and processes, all of which would be more difficult for Database Development

competitors to imitate. Therefore, the capability– In this section, we describe the procedures we followed to

performance relationship may be stronger for studies that develop the database for the meta-analysis. These proce-

use samples of large firms (e.g., revenues or assets greater dures are consistent with those used in previous meta-

than $500 million and also based on author classifications) analyses in marketing (e.g., Brown and Peterson 1993;

than for those that use samples of small firms. Kirca, Jayachandran, and Bearden 2005). First, to create a

Subjective versus objective data. The strength of the comprehensive list of studies of the capability–performance

relationship between capability and performance could vary relationship, we conducted keyword searches of major elec-

according to the type of data used in a study. Capabilities tronic databases (ABI/INFORM, EBSCO, ScienceDirect,

are multidimensional and may not be adequately captured JSTOR) using words and phrases such as “organizational

by the proxy measures used in objective data collection. capabilities,” “competencies,” and “dynamic capabilities.”

Furthermore, because capabilities are deeply routed in orga- Second, we searched the Social Sciences Citation Index for

nizational processes, subjective evaluations of experienced studies that referenced the most-cited articles in the organi-

decision makers may better capture their nuances. However, zational capabilities literature (e.g., Day 1994; Teece,

the correlations obtained from subjective data coud be Pisano, and Shuen 1997). We also manually searched major

inflated as a result of common methods bias. For these rea- marketing and management journals in which articles on

sons, the capability–performance relationship may be organizational capabilities are most likely to be published

stronger for subjective data than for objective data. (e.g., Academy of Management Journal, Decision Sciences,

Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Journal of

Industry type. It is fairly common in meta-analyses in Marketing, Journal of Marketing Research, Management

marketing to examine whether the impact of a particular Science, Marketing Science, Strategic Management

factor on firm performance varies with industry type (e.g., Journal). In addition, we contacted several researchers and

Kirca, Jayachandran, and Bearden 2005). Therefore, we requested working papers and forthcoming articles; we

used the following study characteristics as moderators in posted a similar request on the electronic list servers for

the analysis: whether the effect size is from samples of marketing, management, and international business

manufacturing or services firms and whether the effect size academics.

is from samples of business-to-business organizations or The selection of studies for the meta-analysis was based

business-to-consumer organizations. There is no a priori on several criteria. First, we chose empirical studies that

reason to expect the effect sizes to vary in a specific direc- satisfied the previously discussed definitions of capabilities

tion according to these study characteristics. (examples of different measures coded as capabilities

Geographic context. Prior meta-analyses in marketing appear in the Appendix). Second, we selected studies that

have examined whether the relationship of interest varies in measured capabilities at the organizational level. Finally,

terms of the geographic context of the data. Therefore, we we selected studies that provided the r-family of effects to

coded the studies according to whether the data were from ensure that meaningful comparisons of effect sizes across

firms in the United States or otherwise (Asia, Australia, and different studies could be conducted (Hedges and Olkin

Europe). Again, there is no reason to expect the capability– 1985). On completion of the search process in October

performance relationship to vary in a particular direction 2007, we obtained 114 studies. Because we received few

according to geographic context. unpublished studies, we included only published studies in

Level of study. We also coded studies according to the meta-analysis. We calculated availability bias—that is,

the number of studies reporting null effects for the respec-

whether the data were collected from samples of strategic

tive relationship that is necessary to reduce the cumulative

business units (SBUs) or firms. It is likely that SBUs would

effect to the point of nonsignificance—to allay concerns

be more closely identified with a specific capability, and

about the “file-drawer problem” (see Lipsey and Wilson

therefore studies with data from SBUs might exhibit

2001).2

stronger capability–performance relationships.

Single versus multiple industry data. Whether a study 2A full list of the studies included in the meta-analysis is avail-

focuses on data from firms in a single industry or from able on request.

Marketing, R&D, and Operations Capabilities / 5

To develop the final database, we again followed the mixed-effects models) account for the nested structure of

procedures outlined in recent meta-analyses in the market- the data by modeling within- and between-study variances.

ing literature (e.g., Kirca, Jayachandran, and Bearden The mixed-effects model we employed in this study

2005). We developed a coding protocol to specify the type assumes that the two types of variations in effect sizes can

of information to be extracted from the studies (Lipsey and be explained by the type of capability and performance

Wilson 2001). One of the authors and a doctoral student in variables, as well as other study characteristics. Thus, our

marketing who was not otherwise involved with the study model is as follows:

completed the coding. The two coders initially concurred

(1a) Level 1: Z ij = β 0 j + β1 j × Χ1ij + β 2 j × Χ 2 ij

on approximately 85% of the coded data. Discussion

between the coders helped clarify disagreements and + β3 j × Χ 3ij + ε ij , and

achieve 98% consistency in the coding. The coding of dif-

k

ferent types of capabilities was consistent with their defini-

tions provided previously.3 (1b) Level 2: β nj = γ n 0 + ∑γ nk × U kj + u nj ,

k =1

After compiling the data, we adjusted the effects from

each study for unreliability using the approach that Hunter

where Zij denotes the ith effect size reported within jth sam-

and Schmidt (1990) recommend. We first divided the corre-

ple (j = 1 – 133) and β1j, β2j, and β3j describe parameter

lations by the square root of the product of the reliabilities

estimates (slopes) for the three categorical variables X1j,

of the two correlated constructs. Next, we transformed the

X2j, and X3j, such that

reliability-corrected correlations into z-values (Hedges and

Olkin 1985). Then, we calculated the weighted mean of the X1ij = 1 if the correlation is between R&D capability (R&D)

z-scores using the inverse of their variance (N – 3) as and performance and 0 if otherwise,

weight, where N is the sample size. Finally, we transformed X2ij = 1 if the correlation is between operations capability

the z-scores back to obtain the revised correlation coeffi- (OPER) and performance and 0 if otherwise, and

cients (Hedges and Olkin 1985). X3ij = 1 if the correlation is between capability and market

performance and 0 if the correlation is between capabil-

ity and efficiency performance.

Testing H1, H2, and the Impact of The Level 1 equation (1a) describes the impact of dif-

Study Characteristics Using a ferent capability types and performance measures, which

Mixed-Effects Model vary at a study level, whereas the Level 2 equation (1b)

To test the relative impact of marketing, R&D, and opera- describes the effect of study characteristics on the intercept

tions capabilities on the capability–performance relation- and slopes in the Level 1 equation. The coding scheme was

ship (H1–H2), we used a mixed-effects model. The har- as follows:

vested effect sizes are nested within studies. Nested data U1j = large (1) versus small (0) firms,

structures may lead to heteroskedasticity in the errors from U2j = subjective (1) versus objective (0) data,

traditional regression analysis because correlations from a U3j = business-to-business (1) versus business-to-consumer

study could be more “alike” than correlations from different (0) data,

studies (Beretvas and Pastor 2003; Bijmolt and Pieters U4j = manufacturing (1) versus services (0) data,

2001). Thus, traditional regression analysis may not be U5j = U.S. (1) versus non-U.S. (0) data,

appropriate, because it could produce biased estimates. We U6j = SBU (1) versus firm (0) data, and

tested for heteroskedasticity (White 1980) and found that U7j = multiple (1) versus single (0) industry data.4

the data were indeed of nonconstant error variance (χ274 =

207.40, p < .01). A potential remedy for this problem is to In addition, γn0 (n = 0 – 3) represents the fixed effects in the

average all effects sizes within a study and to use a tradi- intercept and slopes βnj, and unj (n = 0 – 3) describes the

tional moderated regression analysis (e.g., Kirca, Jayachan- unexplained variance (between studies) in the intercept and

dran, and Bearden 2005). However, Bijmolt and Pieters slopes after we partition the effects of study and sample

(2001), Lipsey and Wilson (2001), and Raudenbush and variables.

Bryk (2001) advocate the use of a mixed-effects model to

Results

address the nested structure of the data and to produce more

generalizable results. Indeed, HLMs (a special case of We collected 786 effect sizes for the capability–

performance relationship from 114 studies, with a total

3For coding measures related to new product development capa-

sample size of 30,645. The effect sizes ranged from –.56 to

bility, if a measure focused only on the technological component –.82 in value. As we expected and consistent with prior

of new product development (e.g., integration of technologies, research, we obtained a significant, positive relationship

R&D capability), we coded it as R&D capability. However, if the

measure focused only on the marketing component of new product 4The coding and analysis accounted for contingencies in which

development (e.g., matching changing needs of customers, market some studies did not fit neatly into either of these categories (e.g.,

development), we coded it as marketing capability. A few mea- studies that were a mix of business-to-business and business-to-

sures of new product development capability combined both mar- consumer firms, studies that were a mix of manufacturing and ser-

keting and technological components of new product development vices business, and studies that had data from U.S. and non-U.S.

(e.g., Vorhies and Morgan 2005), and we excluded them from the locations) by developing appropriate contrasts. None of these con-

database to eliminate the risk of confounding. trasts were significant.

6 / Journal of Marketing, July 2008

between capability and performance (r = .283, p < .05). The Discussion and Implications

high numbers for availability bias (4501) suggest that

We designed the study to synthesize and analyze the empiri-

unpublished studies are not a serious threat to the validity of

cal findings on the relationships between different types of

the results. We obtained 319, 206, and 261 effects, respec-

firm capabilities and performance. In the process, we also

tively, for the relationships of marketing capability, R&D

delineated study characteristics that influence the generali-

capability, and operations capability to performance. The

zability of the findings from prior research. Overall, our

sample sizes for marketing capability–performance, R&D

analysis reveals that firm capabilities are positively associ-

capability–performance, and operations capability–

ated with performance over a diverse set of research con-

performance effects are 19,179, 15,766, and 14,675,

texts. An examination of the variance in these relationships

respectively.

using mixed-model analysis demonstrates that marketing

For the test of the hypotheses, we used the

capability has a stronger impact on performance than either

z-transformed values of reliability-corrected correlations

R&D capability or operations capability. To gain further

between capability and performance as the dependent

insights into this, we examined the bivariate correlations

variable. The relevant parameter estimates for the mixed-

between marketing, R&D, and operations capabilities and

effects model appear in Table 1.5 The results of contrasts

performance. Marketing capability had a stronger bivariate

(R&D capability versus marketing capability) indicate that

correlation with performance than R&D capability and

R&D capability (β = –.100, t-value = –3.25) has a lower

operations capability. The mean value for the marketing

impact on firm performance than marketing capability.

capability–performance relationship was .352, whereas the

Thus, H1 was supported. Similarly, we found that, in gen-

corresponding values for R&D capability and operations

eral, operations capability has a lower impact on perfor-

capability with performance were .275 and .205 (all signifi-

mance than marketing capability (β = –.164, t-value =

cant at p < .05). These results support the findings from the

–8.97). Thus, H2 was also supported. The capability–

mixed-model analysis. Among study characteristics, studies

performance effect sizes were higher for market perfor-

with subjective data demonstrated higher capability–

mance than for efficiency performance (β = .051, t-value =

performance correlations, as did studies that examined the

2.01). Consistent with our predictions, the analysis suggests

impact of capabilities on market performance compared

that effect sizes are stronger for subjective data than for

with those that focused on efficiency performance.

objective data (β = .172, t-value = 2.47). The other study

The topic of firm capability is of interest not only to

characteristics did not influence the capability–performance

scholars and managers in marketing but also to their coun-

relationship.

terparts in the areas of operations and R&D and to senior

managers. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first

5We first estimated the intraclass correlation coefficient (ρ), the

attempt to generalize findings in the organizational capabil-

proportion of within-study variance to the total variance (Rauden-

bush and Bryk 2001; Singer 1998; Snijders and Bosker 1994). The

within-study (σ2) and between-study (τ00) variance components els with random effects in different slopes and the intercept. The

are significant and equal to .054 (p < .001) and .067 (p < .001), mixed-effects model with random effects only in the intercept had

respectively. The intraclass correlation coefficient ρ derived from a better fit (–2LLR = 412.4, Akaike information criterion = 416.4,

these estimates was .55 (.067/.121), indicating that more than half and Schwarz’s Bayesian criterion = 421.9) than the model with

the observed variance was between studies and that a fair amount only fixed effects in the intercept and all slopes (–2LLR = 599.9,

of clustering of effect sizes occurred within studies. As such, the Akaike information criterion = 601.9, and Schwarz’s Bayesian cri-

use of HLM is appropriate in this context (Raudenbush and Bryk terion = 606.5). The models with random effects in the intercept

2001). We proceeded with the estimation of the HLM following and either slope or in the intercept and any two slopes did not

the approach that Raudenbush and Bryk (2001) and Singer (1998) demonstrate improvements in fit. Therefore, for hypotheses test-

outline. The model with random effects in the intercept and all ing, we used the model with random effects in the intercept and

three slopes did not converge. Thus, we analyzed alternative mod- fixed effects in the slopes.

TABLE 1

Variance in the Capability–Performance Relationship: Test of Hypotheses and Study Characteristics

Hypotheses d.f. β (t-Value)

Predictor Variables

R&D capability (X1) H1 669 –.100 (–3.25)*

Operations capability (X2) H2 669 –.164 (–8.97)*

Performance type (X3) 669 .051 (2.01)*

Sample Characteristics

Large (1) versus small (0) firms (U1) 103 –.016 (–.27)

Subjective (1) versus objective data (0) (U2) 103 .172 (2.47)*

Business-to-business (1) versus business-to-consumer (0) (U3) 103 –.051 (–.59)

Manufacturing (1) versus services (0) (U4) 103 .050 (.94)

U.S. (1) versus non-U.S. (0) (U5) 103 .039 (.62)

SBU (1) versus firm (0) (U6) 103 –.009 (–.14)

Multiple (1) versus single (0) industry (U7) 103 .023 (.30)

*p < .05.

Marketing, R&D, and Operations Capabilities / 7

ities literature through a meta-analysis. Firm capability is a brand companies is approximately 23.2 months, compared

conceptually broad construct and therefore has been studied with 44.4 months for chief executive officers, 39.4 months

in various contexts and using multiple methods. By summa- for chief financial officers, and 36.4 months for chief infor-

rizing the research from multiple contexts and methods, we mation officers (Von Hoffman 2006). The rapid turnover

help assess the validity and robustness of the capability– among CMOs and the consequent frequent changes in mar-

performance relationship through triangulation (see Hall et keting strategy could be detrimental to the cause of devel-

al. 1993). Moreover, by using a mixed-effects model, the oping strong marketing capabilities. As such, efforts should

study provides a more accurate analysis of the factors that be focused on addressing the causes of CMO turnover in

cause variance in the capability–performance relationship firms.

than would be possible with traditional multiple regression Our results should not be interpreted to mean that

analysis. operations capability and R&D capability are unimportant;

rather, they should underscore the notion that marketing

Limitations capability, which is often jointly formed with customers

Before we assess the implications of these findings, note through relationships, is perhaps much less amenable to

that this study may suffer from several limitations that are competitive imitation or substituted by other forms of

common to other meta-analyses. First, we could not include competitive interference. Note also that both R&D capabil-

all available studies in the meta-analysis because our focus ity and operations capability have strong, positive associa-

was limited to studies that examined capabilities at the firm tions with performance (.275 and .205, respectively). It

or SBU level. Second, in selecting study characteristics that might be the case that marketing capability is more of a

influence the capability–performance relationship, we were “success-producing” capability whereas operations capabil-

constrained to variables that could be coded from the infor- ity and R&D capability tend to be “failure prevention”

mation provided in the studies. In addition, we could capabilities (see Varadarajan 1985). In other words,

include only capabilities for which the impact on perfor- although the efficiency gains from operations capability and

mance was studied frequently enough. Furthermore, it is not new products are critical in ensuring that firms do not lag

feasible in the context of this study to determine whether behind competitors, these capabilities essentially enable

the dynamic nature of the market affects the relative asso- firms to keep rivals at bay. More sustainable competitive

ciation of different capabilities with performance. For advantage could emerge from a success-producing capabil-

example, operations capability might be relatively more ity, such as marketing capability.

important for performance in stable businesses than in We also found that the capability–performance relation-

dynamic businesses. These limitations provide guidelines ship is stronger for market performance than for efficiency

for further research, which we discuss in greater detail performance. To provide additional insights into this issue,

subsequently. we examined the impact of different types of capabilities on

market and efficiency performance measures through con-

Managerial Implications trast coding and HLMs in the same manner in which we

Because capabilities play a dominant role in achieving a conducted the original analysis. From the HLM, we find

sustainable competitive advantage, managers would be that marketing capability and R&D capability have stronger

expected to design strategy to leverage firm capabilities. relationships to market performance than operations capa-

The key finding in this study—that is, the significance of bility (p < .05). An examination of the correlations also sup-

marketing capability in terms of its ability to influence per- ports this result. Marketing capability and R&D capability

formance more so than R&D and operations capabilities— had weighted mean correlations of .355 and .315, respec-

supports Srivastava, Shervani, and Fahey’s (1998, 1999) tively, with market performance, whereas operations capa-

argument that marketing assets are vital for a firm that bility had a weighted mean correlation of .192 with market

wants to augment its shareholder value. Our results are also performance. The HLM results also demonstrate that opera-

consistent with the previously noted observation in the Wall tions capability has a stronger effect on efficiency perfor-

Street Journal that earnings gain from cost cutting (opera- mance than on market performance (p < .05). The corre-

tions capability) has a lower impact on sustained perfor- sponding correlations for operations capability with

mance than earnings gain from strategies that enhance reve- efficiency performance and market performance are .274

nue growth (Zuckerman and Hudson 2007). The results and .192, respectively. As such, it can be concluded that

should also help address the concerns expressed in the busi- operations capability primarily drives efficiency outcomes.

ness media about the value generated by the marketing Overall, capabilities enable firms to reap greater relative

function (e.g., O’Halloran 2004). The superior performance advantage in market performance than efficiency perfor-

impact of marketing capability underscores its ability to mance. This might be a reflection of the notion that opera-

generate tangible benefits, such as effective customer acqui- tions capability, which leads to greater efficiency and flexi-

sition and retention, by managing customer relationships bility, is more mobile through an external market than

and being more responsive to customer needs. Therefore, on marketing capability. Therefore, although operations capa-

the basis of the evidence from prior research, it may not be bility might enhance efficiency performance, there is likely

advisable to reduce investment in marketing capabilities. to be greater parity among competing firms on such gains,

This result should also be of importance to senior manage- thus diminishing the ability to translate these gains into

ment concerned with rapid turnover of chief marketing offi- market performance. For example, efficiency gains that

cers (CMOs). The average CMO tenure in the top 100 should result in a price advantage might be more easily

8 / Journal of Marketing, July 2008

copied than the differentiation advantage that emerges from varies with technological turbulence. Therefore, it is essen-

marketing capability because of the greater imitability and tial to examine directly whether market and technological

mobility of the knowledge that drives operations capability. turbulence influence the relative impact of different capabil-

ities on performance. For example, operations capability

Research Implications might be relatively more significant in stable markets than

Despite the progress in explaining the capability– in turbulent markets. This could be so because of the greater

performance relationship, several gaps in the understanding need for slack resources, the very antithesis of efficiency,

of organizational capabilities can be addressed by addi- for the rapid adaptation that is often required for success in

tional empirical and theoretical research. We detail these turbulent markets. Furthermore, in a new product develop-

research directions next. ment context, R&D and marketing capabilities could be

more important than operations capability. Although we do

Complementary impact of different capabilities. The not have enough data to assess rigorously the value of dif-

results show that marketing capability has a greater impact ferent capabilities in a new product context, an examination

on performance than R&D capability and operations capa- of the correlations for the studies in new product develop-

bility. However, prior research has addressed the issue of ment shows that marketing and R&D capabilities have a

firms developing multiple capabilities simultaneously and stronger relationship to performance than operations capa-

the complementary effects of these capabilities on perfor- bility (.359, .343, and .279, respectively). As such, we

mance. For example, Grewal and Slotegraaf (2007) show encourage a direct, rigorous examination of the role of these

how developing multiple capabilities might be counterpro- capabilities in a new product development context. In addi-

ductive when these capabilities have opposing objectives tion, the importance of more micro capabilities might vary

(minimization versus maximization). Conversely, Moorman on the basis of the market condition. For example, under

and Slotegraaf (1999) show that complementary capabilities what market conditions would pricing capability (Dutta,

help enhance performance. These results are not necessarily Zbaracki, and Bergen 2003) be more critical than customer-

contradictory, because Grewal and Slotegraaf highlight a relating capability (Day 2000)? Research into marketing

specific contingency in which multiple capabilities do not capability should emphasize these issues following in the

help. Thus, a case can be made for multiple, complementary tradition of prior research in this domain (e.g., Vorhies and

capabilities in some situations and single, focused capabili- Morgan 2005).

ties in other situations. However, in the context of a meta-

Methodological issues. From a measurement perspec-

analysis, we are constrained in our ability to address this

tive, we find that studies that use subjective data provide

issue in detail because of sparse data, and thus we encour-

higher correlations for capabilities with performance than

age additional research in this area.

studies based on objective data. Although this could be

Context-based variation of the capability–performance attributable to methods bias, it might also be the case that

relationship. In the meta-analysis, we examined the impact the proxy measures that are employed in objective data col-

of several study characteristics on the capability– lection cannot get at the heart of measuring capabilities.

performance relationship. However, other contextual issues The limitations of secondary data to provide face-valid

are of substantive importance but have not received suffi- measures might be especially pronounced when it comes to

cient attention in the literature. For example, Eisenhardt and assessing more complex capabilities. Thus, an assessment

Martin (2000) note that the nature of capabilities required to of the metrics used to measure capabilities is required to

drive firm performance is likely to vary with the “velocity” shed more light on this issue. Researchers should be cog-

or dynamism of the market. A direct test of this by Song nizant of these measurement-related issues when designing

and colleagues (2005) finds that the impact of marketing future studies to separate effects of capabilities from arti-

and technology capabilities on joint venture performance facts of study design.

Marketing, R&D, and Operations Capabilities / 9

APPENDIX

Examples of Coding of Different Types of Capabilities

Capability Examples of Coding Capability Examples of Coding

Marketing •Dynamic marketing capabilities (Caloghirou Operations •Business process capability (Roth and

et al. 2004) Jackson 1995)

•Marketing planning and implementation •Competence in modular production

capabilities (Vorhies and Morgan 2005) practices (Worren, Moore, and Cardona

•Marketing proficiency (Kim, Wong, and Eng 2002)

2005) •Quality management capabilities (Escrig-

•Trust-building capability (Saini and Johnson Tena and Bou-Llusar 2005)

2005) •Production competence (Hitt and Ireland

•Marketing intensity of multinational 1985)

enterprises (Kotabe, Srinivasan, and •Resource planning and operations

Aulakh 2002) capabilities (Banker et al. 2006)

•Advertising intensity (Anand and Delios

2002) R&D •Innovativeness of patents (Dutta,

•Pricing and distribution capabilities (Zou, Narasimhan, and Rajiv 1999)

Fang, and Zhao 2003) •Stock of R&D capital (Helfat 1997)

•Customer service capability (Moore and •R&D Intensity of multinational enterprises

Fairhurst 2003) (Kotabe, Srinivasan, and Aulakh 2002)

•Customer response capability •Technological innovativeness (Menguc and

(Jayachandran, Hewett, and Kaufman Auh 2006)

2004) •Technological area experience (Macher

and Boerner 2006)

REFERENCES

Anand, Bharat N. and Andrew Delios (2002), “Absolute and Rela- ——— (2000), “Capabilities for Forging Customer Relationships”

tive Resources as Determinants of International Acquisitions,” Marketing Science Institute, Working Paper Series Report No.

Strategic Management Journal, 23 (2), 119–34. 00-118.

——— and Tarun Khanna (2000), “The Structure of Licensing Dutta, Shantanu, Om Narasimhan, and Surendra Rajiv (1999),

Contracts,” Journal of Industrial Economics, 48 (March), “Success in High-Technology Markets,” Marketing Science, 18

103–135. (4), 547–68.

Banker, Rajiv D., Indranil R. Bardhan, Hsihui Chang, and Shu Lin ———, Mark J. Zbaracki, and Mark Bergen (2003), “Pricing

(2006), “Plant Information Systems, Manufacturing Capabili- Process as a Capability: A Resource-Based Perspective,”

ties, and Plant Performance,” MIS Quarterly, 30 (2), 315–37. Strategic Management Journal, 24 (7), 615–30.

Barney, Jay B. (1991), “Firm Resources and Sustained Competi- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. and Jeffrey A. Martin (2000), “Dynamic

tive Advantage,” Journal of Management, 17 (1), 99–120. Capabilities: What Are They?” Strategic Management Journal,

Beretvas, S. Natasha and Dena A. Pastor (2003), “Using Mixed- 21 (10–11), 1105–1121.

Effects Models in Reliability Generalizations Studies,” Educa- Escrig-Tena, Ana Belén and Juan Carlos Bou-Llusar (2005), “A

tional and Psychology Measurement, 63 (February), 75–95. Model for Evaluating Organizational Competencies: An Appli-

Bharadwaj, Sundar G., P. Rajan Varadarajan, and John Fahy cation in the Context of a Quality Management Initiative,”

(1993), “Sustainable Competitive Advantage in Service Indus- Decision Sciences, 36 (2), 221–57.

tries: A Conceptual Model and Research Propositions,” Journal Grant, Robert M. (1996), “Prospering in Dynamically-

of Marketing, 57 (October), 83–99. Competitive Environments: Organizational Capability as

Bijmolt, Tammo H.A. and Rik G.M. Pieters (2001), “Meta- Knowledge Integration,” Organization Science, 7 (July),

Analysis in Marketing When Studies Contain Multiple Mea- 375–87.

surements,” Marketing Letters, 12 (2), 157–69. Grewal, Rajdeep and Rebecca J. Slotegraaf (2007), “Embedded-

Brown, Steven and Robert A. Peterson (1993), “Antecedents and ness of Organizational Capabilities,” Decision Sciences, 38

Consequences of Salesperson Job Satisfaction: Meta-Analysis (August), 451–88.

and Assessment of Causal Effects,” Journal of Marketing ——— and Patriya Tansuhaj (2001), “Building Organizational

Research, 30 (February), 63–77. Capabilities for Managing Economic Crisis: The Role of Mar-

Caloghirou, Yiannis, Aimilia Protogerou, Yiannis Spanos, and Lef- ket Orientation and Strategic Flexibility,” Journal of Market-

teris Papagiannakis (2004), “Industry- Versus Firm-Specific ing, 65 (April), 67–80.

Effects on Performance: Contrasting SMEs and Large-Sized Haas, Martine R. and Morten T. Hansen (2005), “When Using

Firms,” European Management Journal, 22 (2), 231–43. Knowledge Can Hurt Performance: The Value of Organiza-

Capron, Laurence and John Hulland (1999), “Redeployment of tional Capabilities in a Management Consulting Company,”

Brands, Sales Forces, and General Marketing Management Strategic Management Journal, 26 (1), 1–24.

Expertise Following Horizontal Acquisitions: A Resource- Hall, Judith A., Linda Tickle-Degnen, Robert R. Rosenthal, and

Based View,” Journal of Marketing, 63 (April), 41–54. Frederick Mosteller (1993), “Hypotheses and Problems in

Carr, Nicholas G. (2003), “IT Doesn’t Matter,” Harvard Business Research Synthesis,” in Handbook of Research Synthesis, L.V.

Review, 81 (May), 41–49. Hedges and H. Cooper, eds. New York: Russell Sage, 17–28.

Danneels, Erwin (2002), “The Dynamics of Product Innovation Hedges, Larry V. and Ingram Olkin (1985), Statistical Methods in

and Firm Competences,” Strategic Management Journal, 23 Meta-Analysis. Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

(12), 1095–1121. Helfat, Constance E. (1997), “Know-How and Asset Complemen-

Day, George S. (1994), “The Capabilities of Market-Driven Orga- tarity and Dynamic Capability Accumulation: The Case of

nizations,” Journal of Marketing, 58 (October), 37–52. R&D,” Strategic Management Journal, 18 (5), 339–60.

10 / Journal of Marketing, July 2008

——— and Margaret A. Peteraf (2003), “The Dynamic Resource- Saini, Amit and Jean L. Johnson (2005), “Organizational Capabil-

Based View: The Capability Lifecycles,” Strategic Manage- ities in E-Commerce: An Empirical Investigation of E-

ment Journal, 24 (10), 997–1010. Brokerage Service Providers,” Journal of the Academy of Mar-

Hitt, Michael and R. Duane Ireland (1985), “Corporate Distinctive keting Science, 33 (3), 360–75.

Competence, Strategy, Industry and Performance,” Strategic Simonin, Bernard L. (1999), “Transfer of Marketing Know-How

Management Journal, 6 (3), 273–93. in International Strategic Alliances: An Empirical Investigation

Hunt, Shelby D. and Robert M. Morgan (1995), “The Comparative of the Role and Antecedents of Knowledge Ambiguity,” Jour-

Advantage Theory of Competition,” Journal of Marketing, 59 nal of International Business Studies, 30 (3), 463–90.

(April), 1–15. Singer, Judith D. (1998), “Using SAS PROC MIXED to Fit Multi-

Hunter, John E. and Frank L. Schmidt (1990), Methods of Meta- level Models, Hierarchical Models, and Individual Growth

Analysis: Correcting Error and Bias in Research Findings. Models,” Journal of Educational & Behavioral Statistics, 24

Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. (4), 323–55.

Jayachandran, Satish, Kelly Hewett, and Peter Kaufman (2004), Snijders, Tom A.B. and Roel J. Bosker (1994), “Modeled Variance

“Customer Response Capability in a Sense-and-Respond Era: in Two-Level Models,” Sociological Methods and Research, 22

The Role of Customer Knowledge Process,” Journal of the (3), 342–63.

Academy of Marketing Science, 32 (3), 219–33. Song, Michael, Cornelia Droge, Sangphet Hanvanich, and Roger

Kim, Jung-Yoon, Veronica Wong, and Teck-Yong Eng (2005), Calantone (2005), “Marketing and Technology Resource Com-

“Product Variety Strategy for Improving New Product Devel- plementarity: An Analysis of Their Interaction Effect in Two

opment Proficiencies,” Technovation, 25 (9), 1001–1015. Environmental Contexts,” Strategic Management Journal, 26

Kirca, Ahmet, Satish Jayachandran, and William O. Bearden (3), 259–76.

(2005), “Market Orientation: A Meta-Analytic Review and Srivastava, Rajendra K., Tasadduq A. Shervani, and Liam Fahey

Assessment of Its Antecedents and Impact on Performance,” (1998), “Market-Based Assets and Shareholder Value: A

Journal of Marketing, 69 (April), 24–41. Framework for Analysis,” Journal of Marketing, 62 (January),

Kotabe, Masaaki, Srini S. Srinivasan, and Preet S. Aulakh (2002), 2–18.

“Multinationality and Firm Performance: The Moderating Role ———, ———, and ——— (1999), “Marketing, Business Pro-

of Marketing and R&D Activities,” Journal of International cesses, and Shareholder Value: An Organizationally Embedded

Business Studies, 33 (1), 79–97. View of Marketing Activities and the Discipline of Marketing,”

Leonard-Barton, Dorothy (1992), “Core Capabilities and Core Journal of Marketing, 63 (October), 168–79.

Rigidities: A Paradox in Managing New Product Develop- Tan, Keah Choon, Vijay R. Kannan, Jayanth Jayaram, and Ram

ment,” Strategic Management Journal, 13 (Summer), 111–25. Narasimhan (2004), “Acquisition of Operations Capability: A

Levin, Richard C., Alvin K. Klevorick, Richard R. Nelson, and Model and Test Across US and European Firms,” International

Sidney G. Winter (1987), “Appropriating the Returns from Journal of Production Research, 42 (4), 833–51.

Industrial Research and Development,” Brookings Paper on Teece, David J., Gary Pisano, and Amy Shuen (1997), “Dynamic

Economic Activity, 3, 783–831. Capabilities and Strategic Management,” Strategic Manage-

Lipsey, Mark W. and David B. Wilson (2001), Practical Meta- ment Journal, 18 (7), 509–533.

Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Treacy, Michael and Fred Wiersema (1993), “Customer Intimacy

Macher, Jeffrey T. and Christopher S. Boerner (2006), “Experi- and Other Value Disciplines,” Harvard Business Review, 71

ence and Scale and Scope Economies: Trade-Offs and Perfor- (January–February), 84–93.

mance in Development,” Strategic Management Journal, 27 Varadarajan, P. Rajan (1985), “A Two-Factor Classification of

(9), 845–65. Competitive Strategy Variables,” Strategic Management Jour-

Menguc, Bulent and Seigyoung Auh (2006), “Creating a Firm- nal, 6 (4), 357–75.

Level Dynamic Capability Through Capitalizing on Market Vickery, Shawnee K., Cornelia Dröge, and Robert E. Markland

Orientation and Innovativeness,” Journal of the Academy of (1997), “Dimensions of Manufacturing Strength in the Furni-

Marketing Science, 34 (1), 63–73. ture Industry,” Journal of Operations Management, 15 (4),

Moore, Marguerite and Ann Fairhurst (2003), “Marketing Capabil- 317–30.

ities and Firm Performance in Fashion Retailing,” Journal of Von Hoffman, Constantine (2006), “Length of CMO Tenure Con-

Fashion Marketing & Management, 7 (4), 386–97. tinues Decline,” (accessed October 26, 2007), [available at

Moorman, Christine and Rebecca J. Slotegraaf (1999), “The Con- http://www.brandweek.com/bw/search/article_display.jsp?vnu

tingency Value of Complementary Capabilities in Product _content_id=1003020713].

Development,” Journal of Marketing Research, 36 (May), Vorhies, Douglas W. and Neil A. Morgan (2005), “Benchmarking

239–57. Marketing Capabilities for Sustainable Competitive Advan-

O’Halloran, Patrick (2004), “Marketing: Underrated, Underval- tage,” Journal of Marketing, 69 (January), 80–94.

ued, and Unimportant?” (accessed May 7, 2007), [available at Wernerfelt, Birger (1984), “A Resource-Based View of the Firm,”

http://www.accenture.com/Global/Services/By_Industry/ Strategic Management Journal, 5 (2), 171–80.

Communications/Access_Newsletter/Article_Index/Marketing White, Halbert (1980), “A Heteroscedasticity-Consistent Covari-

Unimportant.htm]. ance Matrix Estimator and a Direct Test for Heteroscedastic-

Penrose, Edith Tilton (1959), The Theory of the Growth of the ity,” Econometrica, 48 (4), 817–38.

Firm. New York: John Wiley & Sons. Worren, Nicolay, Karl Moore, and Pablo Cardona (2002), “Modu-

Raudenbush, Stephen W. and Anthony S. Bryk (2001), Hierarchi- larity, Strategic Flexibility, and Firm Performance: A Study of

cal Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. the Home Appliance Industry,” Strategic Management Journal,

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. 23 (12), 1123–40.

Roth, Aleda V. and William E. Jackson III (1995), “Strategic Zou, Shaoming, Eric Fang, and Shuming Zhao (2003), “The Effect

Determinants of Service Quality and Performance: Evidence of Export Marketing Capabilities on Export Performance: An

from the Banking Industry,” Management Science, 41 (11), Investigation of Chinese Exporters,” Journal of International

1720–33. Marketing, 11 (4), 32–55.

Rust, Roland T., Tim Ambler, Gregory S. Carpenter, V. Kumar, Zuckerman, Gregory and Kris Hudson (2007), “Will RadioShack

and Rajendra K. Srivastava (2004), “Measuring Marketing Pro- Lead Investors to a Letdown?” The Wall Street Journal, (April

ductivity: Current Knowledge and Future Directions,” Journal 25), C1–C2.

of Marketing, 68 (October), 76–89.

Marketing, R&D, and Operations Capabilities / 11

You might also like

- Gruen 2010Document15 pagesGruen 2010Jean KarmelNo ratings yet

- Van Hoek2006 Partnering MotivesDocument16 pagesVan Hoek2006 Partnering MotivesJean KarmelNo ratings yet

- Sustainability 09 02218Document13 pagesSustainability 09 02218erkushagraNo ratings yet

- Gruen 2010Document15 pagesGruen 2010Jean KarmelNo ratings yet

- Sugar Technology PDFDocument2 pagesSugar Technology PDFGustavo CardonaNo ratings yet

- Sveiby2001 A Knowledge-BaseDocument23 pagesSveiby2001 A Knowledge-BaseJean KarmelNo ratings yet

- Santarelli2012 The InterplayDocument24 pagesSantarelli2012 The InterplayJean KarmelNo ratings yet

- Uhlik2011 Revisiting TheDocument19 pagesUhlik2011 Revisiting TheJean KarmelNo ratings yet

- ID Sifat Fisik Bakso Daging Sapi Dengan Bah PDFDocument9 pagesID Sifat Fisik Bakso Daging Sapi Dengan Bah PDFErickoNo ratings yet

- Steward 2012 Why Cant A FamilyDocument29 pagesSteward 2012 Why Cant A FamilyJean KarmelNo ratings yet

- Effect of Thawing on Frozen Meat QualityDocument14 pagesEffect of Thawing on Frozen Meat QualityJean KarmelNo ratings yet

- Sullivan2012 Value CreationDocument8 pagesSullivan2012 Value CreationJean KarmelNo ratings yet

- Strategic Orientations Impact on Theater PerformanceDocument17 pagesStrategic Orientations Impact on Theater PerformanceJean KarmelNo ratings yet

- Stam2014 Social Capital ofDocument22 pagesStam2014 Social Capital ofJean KarmelNo ratings yet

- Smirnova2011 The Impact of MarketDocument10 pagesSmirnova2011 The Impact of MarketJean KarmelNo ratings yet

- Scheer2010 The Effects of SupplierDocument15 pagesScheer2010 The Effects of SupplierJean KarmelNo ratings yet

- Sullivan2012 Value CreationDocument8 pagesSullivan2012 Value CreationJean KarmelNo ratings yet

- Schulze2001 Agency andDocument19 pagesSchulze2001 Agency andJean KarmelNo ratings yet

- Selladurai2004 Mass CustomizationDocument6 pagesSelladurai2004 Mass CustomizationJean KarmelNo ratings yet

- Schulze2003 Toward A TheoryDocument18 pagesSchulze2003 Toward A TheoryJean KarmelNo ratings yet

- Vorhies 2000 The CapabilitiesDocument27 pagesVorhies 2000 The CapabilitiesJean KarmelNo ratings yet

- Approaches To Understanding and Measuring Interdisciplinary Scientific Research (IDR) : A Review of The LiteratureDocument13 pagesApproaches To Understanding and Measuring Interdisciplinary Scientific Research (IDR) : A Review of The LiteratureJean KarmelNo ratings yet

- Firm Networks and Firm Development-2Document27 pagesFirm Networks and Firm Development-2Carola KamelNo ratings yet

- Walter 2006 The Impact of Network PDFDocument27 pagesWalter 2006 The Impact of Network PDFJean KarmelNo ratings yet

- Walter 2006 The Impact of Network PDFDocument27 pagesWalter 2006 The Impact of Network PDFJean KarmelNo ratings yet

- Lawson2001 Developing InnovationDocument24 pagesLawson2001 Developing InnovationJean KarmelNo ratings yet

- Lasisi 2014 Business Relationships PDFDocument11 pagesLasisi 2014 Business Relationships PDFJean KarmelNo ratings yet

- Lee2006 Retail Marketing StrategyDocument17 pagesLee2006 Retail Marketing StrategyJean KarmelNo ratings yet

- Lamprinopoulou2011 Inter-Firm RelationsDocument9 pagesLamprinopoulou2011 Inter-Firm RelationsJean KarmelNo ratings yet

- Lado2011 Customer FocusDocument22 pagesLado2011 Customer FocusJean KarmelNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5782)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Sabsa Risk PracDocument6 pagesSabsa Risk Pracsjmpak0% (1)

- Tim Seldin-How To Raise An Amazing Child The Montessori Way-DK (2017)Document210 pagesTim Seldin-How To Raise An Amazing Child The Montessori Way-DK (2017)esthernerja94% (18)

- Kinematics in One Dimension ExplainedDocument16 pagesKinematics in One Dimension ExplainedCynthia PlazaNo ratings yet

- Getting Married Is Not Just LoveDocument1 pageGetting Married Is Not Just LoveAditya Kusumaningrum100% (1)

- Ilya Repin, Krestny Khod (Religious Procession) in Kursk GuberniaDocument6 pagesIlya Repin, Krestny Khod (Religious Procession) in Kursk GuberniadheannainsugradhNo ratings yet

- Importance of Personal GrowthDocument3 pagesImportance of Personal GrowthPrishaNo ratings yet

- Visionary ReportDocument4 pagesVisionary ReportDerek Banas100% (1)

- Harold Bloom'S Psychoanalysis in Peri Sandi Huizhce'S Puisi EsaiDocument5 pagesHarold Bloom'S Psychoanalysis in Peri Sandi Huizhce'S Puisi EsaiAhmadNo ratings yet

- Consonants, Vowels, Diphthongs GreenDocument129 pagesConsonants, Vowels, Diphthongs GreenLen Vicente - Ferrer100% (1)

- Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur: Paste Your Photograph HereDocument3 pagesIndian Institute of Technology Kanpur: Paste Your Photograph HereAvinash SinghNo ratings yet

- (A93) Book Review - The Other Side of SilenceDocument2 pages(A93) Book Review - The Other Side of SilenceGUADALQUIVIR29101991No ratings yet

- Principles and Theories of Language AcquisitionDocument2 pagesPrinciples and Theories of Language AcquisitionElsa Quiros Terre100% (1)

- Cultural Exploration PaperDocument8 pagesCultural Exploration Paperapi-240251499No ratings yet

- NanavatiDocument2 pagesNanavativks3248No ratings yet

- Marlon Steven Betancurt CalderonDocument2 pagesMarlon Steven Betancurt CalderonMARLON STEVEN BETANCURT CALDERONNo ratings yet

- Solving PDEs using radial basis functionsDocument10 pagesSolving PDEs using radial basis functionsHamid MojiryNo ratings yet

- Justitia in MundoDocument16 pagesJustitia in Mundokwintencirkel3715No ratings yet

- The Enigma René Guénon and Agarttha (V) : Review by Mircea A. TamasDocument5 pagesThe Enigma René Guénon and Agarttha (V) : Review by Mircea A. Tamassofia_perennisNo ratings yet

- A Manual of RespirationDocument32 pagesA Manual of RespirationSabyasachi Mishra100% (1)

- List of Least-Learned Skills/Competencies and Intervention: Datu Lipus Macapandong National High SchoolDocument28 pagesList of Least-Learned Skills/Competencies and Intervention: Datu Lipus Macapandong National High SchoolChristine Pugosa InocencioNo ratings yet

- Havighurtst TheoryDocument4 pagesHavighurtst TheoryGarima KaushikNo ratings yet

- PillarsDocument38 pagesPillarsBro A A Rashid100% (4)

- Chapter 8 - Organizational Culture Structure and DesignDocument55 pagesChapter 8 - Organizational Culture Structure and DesignEvioKimNo ratings yet

- Language Study Material XiDocument8 pagesLanguage Study Material XiPrabhat Singh 11C 13No ratings yet

- Age of Ambition (Excerpt)Document6 pagesAge of Ambition (Excerpt)The WorldNo ratings yet

- A Source Book KrishnaDocument590 pagesA Source Book KrishnaSubhankar Bose75% (8)

- 055 - Ar-Rahman (The Most Graciouse)Document28 pages055 - Ar-Rahman (The Most Graciouse)The ChoiceNo ratings yet

- Tiffany InglisDocument6 pagesTiffany Inglisjuan perez arrikitaunNo ratings yet

- INT AC19 Training Series Vol 1Document43 pagesINT AC19 Training Series Vol 1Alexandra PasareNo ratings yet

- Albert CoopdischoDocument3 pagesAlbert Coopdischoapi-2545973310% (1)