Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ir Sensitivity of Tax Exempt Bonds Joim

Uploaded by

soumensahilCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ir Sensitivity of Tax Exempt Bonds Joim

Uploaded by

soumensahilCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal Of Investment Management, Vol. 12, No. 1, (2014), pp.

62–68

© JOIM 2014

JOIM

www.joim.com

THE INTEREST RATE SENSITIVITY OF TAX-EXEMPT

BONDS UNDER TAX-NEUTRAL VALUATION

Andrew Kalotaya

We explore the effect of taxes on the prices of municipal bonds. Although interest is tax-

exempt, the gain resulting from purchasing a muni at a deep discount—below the so-called

de minimis threshold—is subject to severe tax treatment. The gain is taxed as ordinary

income at maturity; currently for a typical investor the applicable rate is roughly 40%.

Thus, purchasing a bond at 80 would trigger an 8-point tax liability.

The paper develops a rigorous approach to the pricing of munis by incorporating taxes

into the industry-standard OAS-based valuation framework. The key concept is ‘tax-neutral

value’, which is simply the fair value that takes into account potential tax payments. Tax-

neutral valuation allows us to explore how muni prices respond to changing interest rates.

The basic insight is that due to the interaction of the purchase price and the related tax

payment, discount tax-exempt bonds are significantly more sensitive to interest rates than

taxable bonds. For example, currently the duration of a 10-year taxable bond is roughly

8.5 years, while that of a 10-year muni can exceed 13 years.

Tax-neutral valuation provides the foundation for accurately projecting the prices of

munis under various interest rate scenarios. The primary application of this approach is

risk management, including hedging. It is also essential for determining the optimum time

to recognize a loss in order to maximize after-tax performance.

1 Introduction capital gains and losses are subject to complex tax

treatment. Taxes affect investors’ after-tax per-

While interest payments on municipal bonds formance. For example, because the gain on a

(‘munis’) are exempt from federal income taxes, bond purchased in the secondary market at a dis-

count and held to maturity is subject to taxes,

a President, Andrew Kalotay Associates, Inc., 61 Broadway, the after-tax yield of the investment will be lower

Suite 1400, New York, NY 10006, USA. Tel.: (212) 482 than the pretax yield. The prices of discount tax-

0900; E-mail: andy@kalotay.com exempt bonds are routinely converted to so-called

62 First Quarter 2014

The Interest Rate Sensitivity of Tax-Exempt Bonds under Tax-Neutral Valuation 63

after-tax cashflow yields to maturity. Converting Investors who purchase a bond in the secondary

price to an after-tax yield is straightforward, market at a discount and hold it to maturity or call

and it allows investors to compare alternative are taxed on the gain. At a modest discount to par

investments on an-apples-to-apples basis. (a so-called de minimis discount, defined as less

than 0.25 times the number of years remaining to

The prices of tax-exempt bonds reflect these com-

maturity) the applicable rate is the relatively low

plex tax considerations. This phenomenon is well

capital gains rate (at the time of writing, 20% if

recognized by practitioners but their attempts to

long-term). If the discount exceeds the de minimis

deal with the effects analytically have been lim-

threshold, the entire gain is taxed at the higher

ited to using yields and modified durations, and

ordinary income rate (around 40% at the time of

not contemporary fixed income analytics (e.g. see

writing). We also note that the loss on a bond

Leibowitz, 1981; Merrill Lynch, 2007). In this

purchased at a premium and held to maturity has

paper we will extend the conventional arbitrage-

no tax effect.

free method of bond valuation (the so-called

option-adjusted spread approach) to incorporate The tax treatment is more complicated if the bond

tax effects. We first determine the tax-neutral is sold prior to maturity or call. But because the

(‘fair’) value of a bond assuming a buy-and-hold values in the current discussion are based on buy-

policy. This fair value provides the basis for rigor- and-hold, we ignore taxation related to sales.

ous risk analysis.1 As we shall see, the interest rate

sensitivity of a muni can be significantly greater

3 Market prices of munis

than that of a like taxable bond.

The obvious first question to explore is the rea-

The implications of this observation are far-

sonableness of the assumption that market prices

reaching. At the present, standard commercially

can be imputed from a buy-and-hold strategy. On

available analytical systems do not take taxes into

the one hand, Constantinides and Ingersoll (1984)

account. This is particularly troublesome in the

argue that active tax management can produce

case of exchange traded funds and mutual funds

superior return over buy-and-hold. This would

that attempt to replicate the performance of a

imply that market prices should be higher than

large index—which may consist of over 10,000

that indicated by buy-and-hold. On the other hand,

bonds—with a few hundred securities. Matching

there is scant empirical evidence that such is the

durations on a pretax basis does not assure that

case. In fact, according to Ang et al. (2010),

the same relationship holds when the effect of

the market prices of deep discount munis are

taxes is properly accounted for. In light of this,

significantly lower than would be implied by buy-

the large tracking errors of these ‘index-matching’

and-hold, and they provide a possible explanation

portfolios do not come as a surprise.

for this phenomenon.

In any case, for risk management purposes it is

2 Relevant tax treatment

irrelevant whether the actual prices are marginally

A thorough discussion of the tax treatment of higher or lower than that indicated by buy-and-

munis, including original issue discount bonds hold. The relevant fact is that prices of munis do

(OIDs) and original issue premium bonds (OIPs), reflect the presence of taxes, and our approach

is provided by Ang et al. (2010). For illustrative could be readily adapted to pricing models more

purposes, we will assume that the bonds under sophisticated than ‘buy-and-hold’, should such

consideration were originally sold at par. become available.

First Quarter 2014 Journal Of Investment Management

64 Andrew Kalotay

4 Methodology the case of a callable bond the fair value has to

be determined iteratively, as the timing of the

Our initial goal is to determine the tax-neutral

tax payment depends on the evolution of inter-

value (‘fair value’) of tax-exempt munis using

est rates. The calculation can be simplified if the

arbitrage-free analysis (see Kalotay et al. (1993)).

bond is optionless, as illustrated below.

In the absence of taxes and options, fair value is

obtained by discounting prospective cash flows at Assume that the bond has 10 years remaining to

the appropriate spot rates; if options are present, maturity, its pretax value is 80, the discount factor

such discounting is performed on a lattice. The for a cash flow occurring 10 years from now is

taxation of munis complicates the calculation 0.45, and the tax rate applicable to the gain is

because the cash flows depend on the purchase 40%. Solving

price; roughly speaking, the lower the purchase

V = 80 − 0.45 × 0.40 × (100 − V )

price the more taxes will be due when the bond is

retired. gives the fair value V = 75.610.

Figure 1 displays the fair values of 10-year bonds

4.1 Practical considerations with various coupons. For comparison purposes,

Arbitrage-free valuation requires an issuer- we also show the values in the absence of taxes.

specific optionless (par) yield curve for discount- The calculations are based on the yield curve

ing, and for valuing options at a specified interest displayed in Table 1. The assumed volatility for

rate volatility. In the case of tax-exempt bonds, callable bonds (see Figure 3) is 20%. The long-

optionless long-term rates are not readily avail- term capital gains rate is 20%, and the tax rate

able, because the industry-standard MMD and applicable to ordinary income is 40%.

MMA yield curves assume that the underly- Note that the pretax value of a discount muni

ing bonds are callable at par after 10 years. exceeds its fair value by the present value of

The approach of extracting optionless par curves the taxes paid at the time the bond is redeemed.

from callable curves is described in Kalotay and (The discount rate applied to the tax payment is

Dorigan (2008). The numerical examples below

assume that the optionless curve has been pro-

vided and that it evolves according to an industry-

standard lognormal process. Our methodology,

of course, is applicable to arbitrary interest rate

processes.

5 Tax-neutral value

We now determine the value of a bond under

the buy-and-hold strategy. We define the tax-

Figure 1 Fair value of 10-year bonds.

neutral (fair) value as the price which is equal

to the present value of after-tax cashflows (i.e.

interest and principal payments minus the taxes Table 1 Issuer’s optionless par yield curve.

paid at the time of redemption). Simply put, the

Maturity (yrs) 1 2 5 10 15 20 30

fair value is the ‘pretax’ value adjusted for taxes.

Rate (%) 1.0 1.5 2.0 3.0 3.5 4.0 4.5

Because taxes depend on the purchase price, in

Journal Of Investment Management First Quarter 2014

The Interest Rate Sensitivity of Tax-Exempt Bonds under Tax-Neutral Valuation 65

the spot rate derived from the issuer’s yield curve.)

Here the de minimis threshold is 97.50% of par

(100 − 10 × 0.25). In the absence of taxes, a

bond with a 2.72% coupon would be valued at

97.50 (blue line), but due to the tax on the gain

the value would be less. Conspicuous in Figure 1

is how the fair value (red line) ‘falls off the cliff’

at the de minimis level. The ‘critical’ coupon (dis-

cussed below) is 2.76%. If the coupon is 2.75%,

the fair value declines by 0.60% to about 96.90.

The reason is that above 97.50 the gain is taxed Figure 3 Fair value of 30-year NC10’s.

at the 20% capital gains rate, but below 97.50 the

gain is taxed at 40%. In comparison to Figure 2, the presence of the call

The de minimis threshold with 30 years to matu- option reduces both the pretax and after-tax val-

rity is 92.50%. The critical coupon for a bullet is ues. In the case of lower-coupon bonds the results

4.10%; at 4.09% the fair value drops by 0.36% are similar to those in Figure 2, because the effect

to 92.14 (red line). The effect is less pronounced of the call option is relatively insignificant. In the

than in Figure 1, because the maturity is farther case of higher-coupon bonds the tax effect is rel-

away. In the absence of taxes, a coupon of 4.07% atively insignificant to begin with, because the

would give a 92.50% value (blue line). price is closer to par.

As discussed above, it is more difficult to deter-

mine the fair value of a callable bond than that 5.1 Critical coupon level

of a bullet, because the redemption date is uncer- As we saw in the examples above, for a given yield

tain and in turn so is the present value of the tax curve and bond structure (i.e. maturity and option-

payment. We also note that the redemption date ality) there is a theoretical coupon level where the

depends on the interest rate volatility (assumed to fair value falls off the cliff. While in reality the

be 20% in the illustration below). Thus in this case price decline is not as abrupt as indicated by our

the fair value must be calculated by lattice-based model, this critical coupon level is still of prac-

recursion. tical interest. If a bond is purchased at a price

slightly above the de minimis threshold, its price

could decline significantly even if rates rise only

modestly. Because the market anticipates this pos-

sibility, the price experiences downward pressure

when the coupon is slightly above the critical

level. Similarly, the price can be higher than that

predicted by our model if the coupon is slightly

lower than the critical level. Price behavior near

the de minimis level is of independent interest and

could be explored as a separate study.

We also observe that while market prices are

Figure 2 Fair value of 30-year bullets. extremely important to investors whose portfolios

First Quarter 2014 Journal Of Investment Management

66 Andrew Kalotay

must be marked to market (such as mutual funds The general approach to determining interest rate

and ETFs), they are less significant for buy-and- risk is as follows:

hold investors. The point is that the value of the

(1) Determine the OAS of the bond at the given

remaining cashflows to an existing investor can be

price relative to the benchmark yield curve.

higher or lower than to a marginal buyer. This is

(2) Shock the yield curve.

discussed in Kalotay and Howard (forthcoming).

(3) Reprice the bond at the OAS obtained in (1).

For a given yield curve, the critical coupon of an (4) Calculate risk measures.

optionless can be determined easily (see below). In the case of tax-exempt bonds, it is imperative

For a callable bond the calculation is obviously to recognize that the prices may be depressed by

more complicated. potential tax payments; otherwise the interest rate

Illustration: Determining the Critical Coupon C sensitivity can be severely underestimated. The

of an Optionless 10-Year Bond intuition is clear: higher rates depress the price,

and a lower price increases taxes. The OAS should

Assume the present value of a 10-year $1 annuity be an indication of only credit risk or mispricing,

is $8.50, the discount factor for a cash flow occur- but it should not reflect tax effects. The appro-

ring 10 years from now is 0.70, and the capital priate spread measure for munis is tax-neutral

gains rate is 20%. Solving OAS, that is, the OAS that equates the price to

the tax-neutral value.

8.50 × C + 0.70 × (100 − 0.20 × 2.50)

Naturally the higher the applicable tax rate the

= 97.50,

greater is the above effect, so it is most pro-

results in C = 3.28%. nounced when the price is below the de minimis

threshold. At the de minimis threshold the price

Note that the fair value of a bond whose coupon is discontinuous, and therefore interest rate sensi-

is slightly below 3.28% is tivity is not defined. Whenever the tax treatment

is discontinuous it is desirable to distinguish

97.50 − 0.70 × (0.40 − 0.20) × 2.50 = 97.15,

between ‘up’ and ‘down’ durations.

which accounts for the incremental tax bill arising The exhibits below display the durations of vari-

from the applicability of the ordinary income tax ous tax-exempt bond structures using tax-neutral

rate (40%) over the tax bill arising from applying prices (based on the benchmark curve).

the short-term gain rate (20%).

Figure 4 displays the durations of 10-year

optionless bonds. As we saw in Figure 1, the

6 The interest rate sensitivity of critical coupon in this case is 2.76%. The

tax-exempt bonds durations of bonds with coupon below 2.76%

exceeds 12 years, which is 2 years longer

In the preceding sections of this paper we devel-

than the bonds’ maturity! Duration slightly

oped a tax-neutral valuation model for tax-exempt

exceeds 10 years even in the de minimis

bonds assuming buy-and-hold, and explored the

region (coupons larger than 2.76% but less than

behavior of this model for various bond structures.

3.00%).

Given the above foundation, we are ready to inves-

tigate the interest rate sensitivity of tax-exempt Since the pretax duration of a bond cannot exceed

bonds. the bond’s maturity, any calculator that disregards

Journal Of Investment Management First Quarter 2014

The Interest Rate Sensitivity of Tax-Exempt Bonds under Tax-Neutral Valuation 67

again when it falls below 92.50 (the de min-

imis threshold price occurring at around a 4.33%

coupon).

There is an obvious extension to key rate durations

(not discussed here).

6.1 Observations about ‘pretax’

risk measures

Figure 4 Duration of 10-year optionless bonds.

As described at the beginning of this section, inter-

est rate risk measures are calculated using a fixed

taxes will severely underestimate the true duration

OAS relative to a benchmark yield curve. Note

of discount bonds. But the error is significant even

that OAS depends on whether or not tax effects

if the price is close to par—for example, the pretax

are incorporated.

duration of a bond in the de minimis region is 8.85

years, considerably shorter than the true duration. Example: Solve for OAS, Calculate Duration

It is well known that taxes can have a drastic Suppose that the price of an optionless 10-year

effect on interest rate sensitivity. For example, 2.5% bond is 84.15; calculate its OAS relative to

as pointed out by Kalotay (1984), the after-tax the benchmark curve given earlier.

duration of an original issue discount bond issued

Pretax (incorrect): OAS = 147 bps, dura-

by a taxable corporation can exceed the bond’s

tion = 8.87 years

maturity.

Tax-neutral: OAS = 90 bps, duration = 12.14

Figure 5 below shows similar information for 30- years

year bonds callable in 10 years. As long as the Correct calculation of interest rate risk requires

price is below par, the duration is longer than an explicit adjustment for taxes. In the absence of

it would be in the absence of taxes (latter not such, the risk of tax-exempt bonds is underesti-

shown). The duration is not defined when the price mated.

is discontinuous—in this case when it declines

below par (slightly below a 5.00% coupon) and

7 Conclusion

It is generally recognized that taxes on capital

gains depress the prices of tax-exempt bonds. We

have presented a rigorous approach to incorpo-

rating this effect in the valuation of tax-exempt

bonds. Specifically, we extended the conventional

OAS framework to after-tax analysis, including

tax-neutral value and tax-neutral OAS.

Using tax-neutral values as a foundation, we have

shown that the interest rate sensitivity of tax-

Figure 5 Duration of 30NC10 bonds. exempt bonds can be significantly greater than

First Quarter 2014 Journal Of Investment Management

68 Andrew Kalotay

that indicated by pretax calculation, which unfor- Constantinides, G. M. and Ingersoll, J. E. (1984). “Optimal

tunately is the current standard in the industry. The Bond Trading with Personal Taxes,” Journal of Financial

difference is most pronounced for shorter-term Economics 13(3), 299–335.

Kalotay, A. (1984). “An Analysis of Original Issue Discount

bonds selling below the de minimis level, whose

Bonds,” Financial Management (Autumn), 29–38.

duration can exceed their maturity by several Kalotay, A. and Dorigan, M. (2008). “What Makes the

years. Municipal Yield Curve Rise,” Journal of Fixed Income

(Winter), 65–71.

In light of the fact that under current prac- Kalotay, A. and Howard, C. D. “The Tax Option in

tice the interest rate sensitivity of tax-exempt Municipal Bonds,” Journal of Portfolio Management.

bonds is miscalculated, the large tracking errors forthcoming.

of ‘index-matched’ ETFs and mutual funds are Kalotay, A., Williams, G., and Fabozzi, F. (1993). “A Model

not surprising. Tax-adjusted analytics are essen- for Valuing Bonds and Embedded Options,” Financial

tial for proper management of tax-exempt bond Analysts Journal (May/June), 34–46.

Leibowitz, M. (1981). “Volatility in Tax-Exempt Bonds: A

portfolios.

Theoretical Model,” Financial Analysts Journal (Novem-

ber/December).

Note Merrill Lynch (not an individual) (2007). “Dealing with

Deeper Discounts,” Muni & Derivatives Commentary

1 Tax-neutral values, durations, and other values in (June 18), 1–2.

this paper were calculated using Kalotay Analytics’

MuniOASTM library (patent pending).

Keywords: Municipal bonds; tax-neutral value;

taxes; duration; de minimis rule; bond valuation;

References after-tax; interest rate sensitivity; risk manage-

Ang, A., Bhansali, V., and Xing, Y. (2010). “Taxes on Tax- ment; tax-neutral OAS; option-adjusted spread;

Exempt Bonds,” Journal of Finance 65(2), 565–601. critical coupon

Journal Of Investment Management First Quarter 2014

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Solving Mathematical Problems A Personal Perspective (Tao)Document57 pagesSolving Mathematical Problems A Personal Perspective (Tao)soumensahilNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Banorte MXN FX Strategy Mar 2016Document17 pagesBanorte MXN FX Strategy Mar 2016soumensahilNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- (JPMorgan) Credit Derivatives - A Primer (2005 Edition) PDFDocument36 pages(JPMorgan) Credit Derivatives - A Primer (2005 Edition) PDFsoumensahilNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- 16-06-27 - Latam Opportunities After The ReferendumDocument4 pages16-06-27 - Latam Opportunities After The ReferendumsoumensahilNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Thomas Hawkins Lebesgues Theory of Integration Its Origins and Development 1975 PDFDocument244 pagesThomas Hawkins Lebesgues Theory of Integration Its Origins and Development 1975 PDFsoumensahil100% (3)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Applications of Random Matrix Theory To Principal Component Analysis (PCA)Document25 pagesApplications of Random Matrix Theory To Principal Component Analysis (PCA)soumensahilNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Research 2013 Interest Rate SwapsDocument45 pagesResearch 2013 Interest Rate SwapssoumensahilNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- SSRN Id2419243Document20 pagesSSRN Id2419243soumensahilNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- SSRN Id2298565Document63 pagesSSRN Id2298565soumensahilNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- SSRN Id2403067Document19 pagesSSRN Id2403067soumensahilNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id2276632Document16 pagesSSRN Id2276632soumensahilNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- 7.1 AFM - International Investment Appraisal - 251223Document17 pages7.1 AFM - International Investment Appraisal - 251223Kushagra BhandariNo ratings yet

- Escaping The Fragility TrapDocument79 pagesEscaping The Fragility TrapJose Luis Bernal MantillaNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Business EconomicsDocument23 pagesBusiness Economicsdeepeshvc83% (6)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- M Venkateswara RaoDocument2 pagesM Venkateswara Raovenkat marellaNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

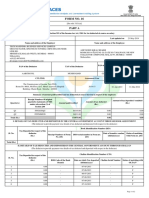

- Form No. 16: Part ADocument2 pagesForm No. 16: Part AasifNo ratings yet

- VERELL LERIAN - 008201800048 - SUMMARY CH 10 Ethics Applied To The AccountingDocument3 pagesVERELL LERIAN - 008201800048 - SUMMARY CH 10 Ethics Applied To The AccountingVerell LerianNo ratings yet

- WeBOC Registration RequirementDocument3 pagesWeBOC Registration RequirementbehindthelinkNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Practice Test 1 KeyDocument11 pagesPractice Test 1 KeyAshley Storey100% (1)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Ilovepdf Merged PDFDocument124 pagesIlovepdf Merged PDFRuann Albete Fernandez25% (4)

- Admelec Cases 1 28 SAT RECITDocument29 pagesAdmelec Cases 1 28 SAT RECITKkee DdooNo ratings yet

- Trusts and Estates - Edmisten - Summer 2003 - 3Document6 pagesTrusts and Estates - Edmisten - Summer 2003 - 3champion_egy325No ratings yet

- Rubio Vs CIRDocument3 pagesRubio Vs CIRJoovs JoovhoNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- 2011 Pub 4491WDocument208 pages2011 Pub 4491WRefundOhioNo ratings yet

- J. Bersamin TaxDocument14 pagesJ. Bersamin TaxJessica JungNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Muslim League-N Manifesto For 2018 ElectionsDocument3 pagesPakistan Muslim League-N Manifesto For 2018 ElectionsThair YaseenNo ratings yet

- Form 16 (2022-23) Assessment Year 2023-24Document6 pagesForm 16 (2022-23) Assessment Year 2023-24Hidden future techNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Thai Localized Manual 46CDocument135 pagesThai Localized Manual 46Cirresistiblerabbits100% (1)

- Work Book: 7 Steps To Jobs, Careers and God's CallingDocument14 pagesWork Book: 7 Steps To Jobs, Careers and God's CallingTim KraussNo ratings yet

- Optional Standard Deduction - Special Deductions (Gross Income)Document2 pagesOptional Standard Deduction - Special Deductions (Gross Income)Trixie Jane NeriNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Court of Tax Appeals Quezon CityDocument16 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Court of Tax Appeals Quezon CityEvan TriolNo ratings yet

- Hector SDocument3 pagesHector SFerrer Benedick50% (2)

- 2022 Tax TableDocument3 pages2022 Tax TableDiwakar reddyNo ratings yet

- Essay 01 - Homework: (việc giao bài tập về nhà)Document9 pagesEssay 01 - Homework: (việc giao bài tập về nhà)Ngô Anh TàiNo ratings yet

- Steps To Start A Small Scale IndustryDocument3 pagesSteps To Start A Small Scale Industrysajanmarian80% (5)

- Centre State RelationsDocument9 pagesCentre State RelationsBuNo ratings yet

- Annual Report Project On Muthoot Finance LTDDocument41 pagesAnnual Report Project On Muthoot Finance LTDAlicia Duncan50% (2)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- What Is Indivisible Works ContractDocument1 pageWhat Is Indivisible Works ContractAnonymous Q3J7APoNo ratings yet

- Employee'S Provident Fund Organisation: Electronic Challan Cum Return (Ecr)Document1 pageEmployee'S Provident Fund Organisation: Electronic Challan Cum Return (Ecr)Vora ParvejNo ratings yet

- L-1 & 2 Tax Meaning and TypesDocument29 pagesL-1 & 2 Tax Meaning and TypesSamriti NarangNo ratings yet

- PF Form 15GDocument1 pagePF Form 15GSorabh BhargavNo ratings yet