Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Depressive Symptoms in Young Adolescence

Uploaded by

doina2008Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Depressive Symptoms in Young Adolescence

Uploaded by

doina2008Copyright:

Available Formats

Prevalence of Self-Reported Depressive Symptoms

In Young Adolescents

VICTOR J. SCHOENBACH, MSPH, PHD, BERTON H. KAPLAN, PHD, EDWARD H. WAGNER, MD, MPH,

ROGER C. GRIMSON, PHD, AND FRANCIS T. MILLER, PHD

Abstract: To investigate the significance and measurement of reported persistent vegetative symptoms less often and psychoso-

depressive symptoms in young adolescents, 624 junior high school cial symptoms more often. Reports of symptoms without regard to

students were asked to complete the Center for Epidemiologic duration were much more frequent in the adolescents, ranging from

Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) during home interviews. In 384 18 per cent to 76 per cent in White males, 34 per cent to 76 per cent

usable symptom scales, item-scale correlations (most were above in White and Black females, and 41 per cent to 85 per cent in Black

.50), inter-item correlations, coefficient alpha (.85), and patterns of males. The results support the feasibility of using a self-report

reported symptoms were reasonable. Persistent symptoms were symptom scale to measure depressive symptoms in young adoles-

reported more often by Blacks, especially Black males. Prevalence cents. Transient symptoms reported by adolescents probably reflect

of persistent symptoms in Whites was quite close to reported figures their stage of development, but persistent symptoms are likely to

for adults, ranging from I per cent to 15 per cent in adolescent males have social psychiatric importance. (Am J Puiblic Health 1983;

and 2 per cent to 13 per cent in adolescent females. Adolescents 73:1281-1287.)

Introduction permission for the study, a school was chosen at random

from among several having the above characteristics.

Depressive symptoms, such as feeling sad, lonely, or Although the school roster listed 728 names, it devel-

worthless, are common in young adolescents, but of uncer- oped that 119 of these students had moved from the area or

tain significance.' 2 Such symptoms may occur as part of a had been transferred to other schools. Fifteen students not

depressive syndrome, but otherwise are not regarded as listed but attending the target school were discovered during

clinically important.34 When severe, persistent, or recur- door-to-door canvassing, bringing the total number of eligi-

rent, however, symptoms may be meaningful from a social ble subjects to 624. Of these 624, 120 (19 per cent) were not

psychiatric perspective in which they and other "behaviors interviewed due to refusal of the parent to give informed

of psychiatric interest"5 can be related to social and cultural consent (N = 75) or to refusal of the subject to participate (N

phenomena. = 45). Information in the roster indicated that refusals were

The interpretation of depressive symptoms in adoles- evenly distributed by grade level and by sex. However,

cents is particularly problematic, because of: controversy interviewers reported that refusal rates were higher in appar-

about the existence, prevalence, manifestations, and diagno- ently middle class households than in either well-to-do or

sis of depression as a pediatric psychiatric disorderi4-8; lower income households, perhaps due to the sensitive

uncertainty about possible influences of biological and other nature of the questionnaire. This bias plus the exceptional

normal developmental processes on moods and behavior9'0: income and educational backgrounds of the students attend-

and limitations in data about the prevalence, severity, dura- ing the target school (see "Results") indicate that the

tion, and distribution of depressive symptoms in this age prevalences to be presented must be interpreted with cir-

group.' 2 A basic obstacle to research has been the absence cumspection. For an additional 120 subjects (19 per cent),

of validated measurement instruments."I The present study depressive symptom scales were omitted by the subject or

investigated the feasibility of measuring early adolescent were judged unsuitable for analysis. Sociodemographic data

depressive symptoms by using an adult symptom scale. were available for this latter group of nonrespondents and

are presented in the "Results" section.

Methods Interviews, conducted in the subject's home, included

Depressive symptom data were obtained in conjunction questions on sociodemographic data, physical development,

with a pilot study of biosocial factors in adolescent sexual sexual feelings, attitudes, and experience, relationships with

behavior.'2 Requirements of that study dictated a study parents and peers, and depressive symptoms during the past

population of between 500 and 1,000 students attending a week. The interviewer administered the initial section on

junior high school with grades seven through nine in one household composition, age, grade level, parental education,

building. For the first North Carolina school district to give and other routine factors, and remained available to answer

questions. Otherwise, the subject's responses were self-

recorded and were not known to interviewer or parents.

From the Department of Epidemiology, University of North Carolina Measures taken to assure subjects that their responses

School of Public Health. Address reprint requests to Dr. Victor J. Schoen- would be kept in confidence were judged to be adequate on

bach, Research Assistant Professor, Department of Epidemiology, Rosenau the basis of a pretest phase. Seventy per cent of the mothers

Hall 201-H, University of North Carolina, School of Public Health, Chapel and 17 per cent of the fathers completed a shorter question-

Hill, NC 27514. This paper, submitted to the Journal April 19, 1982, was

revised and accepted for publication January 17, 1983. naire at the same time.

The adolescent questionnaire, less the depressive symp-

© 1983 American Journal of Public Health 0090-0036/83 $1.50 tom component, was worded for sixth-grade reading level

AJPH November 1983, Vol. 73, No. 11 1281

SCHOENBACH, ET AL.

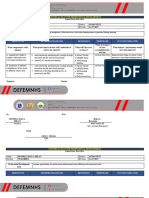

TABLE 1-Per Cent of Usable Depression Scales by Characteristics of Subjects Interviewed

White Black White Black

Males Males females Females Total

(N = 153) (N = 104) (N = 155) (N = 92) (N = 504)

Characteristics

Age (years)

12 62t 61 77 81 73

13 77 44 90 83 73

14 86 74 96 76 86

15-16 67 63 83 74 70

Grade

7 70 44 81 78 69

8 80 61 94 86 81

9 78 72 90 70 80

Natural Father

In Home 79 60 86 76 79

Deceased 50t 70 1 00t 100 82

Divorced/other 74 50 91 75 70

Parental education*

Less than 12 years 64 53 94 75 65

12-15 years 74 61 88 82 77

16 years or more 86 50t 89 67t 86

TOTAL 76 57 88 78 76

*Number of years of school completed by natural parent living at home; if both natural parents present, then the higher value was

used.

tFewer than 10 subjects in this category.

and had been pretested several times with junior and senior of the time." "Present" refers to any response other than

high school students. A validation study of the physical the non-depressive one ("Rarely or none of the time" for a

development items, carried out in pediatricians' offices in negative item, "Most or all of the time" for a positive item).

Lake County, Illinois, yielded Pearson correlations ranging The response alternatives are hereinafter abbreviated as

from .50 to .80 (all significant at the 5 per cent level) between "Rarely," "Some," "A lot," "Most."

adolescent and pediatrician ratings of genital hair and global

rating of adolescent development.3 In the present data, Results

correlations of height with weight, pubertal development Subject Characteristics

with age, and sexual experience with physical maturity and Table I presents response rates (proportions of usable

sexual attitudes allayed initial concerns that the adolescents depression scales among subjects interviewed) by selected

might not respond to the questionnaire in a serious manner. subject characteristics. Characteristics associated with high-

Spearman correlations between the adolescent's report of er response rates were female sex, White race (among

his/her parents' years of schooling and the parental report, males), and parental education (except White females [WF]).

where available, ranged from .77 to .85 for four race-sex Many of the 84 subjects who skipped the depression scale

groups. entirely also omitted other pages that contained a large

Depressive symptom data were collected using a self- number of items, possibly due to poor reading ability. These

report version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies differential response rates should be kept in mind in inter-

Depression Scale (CES-D)'4 with slightly altered response preting the results. As discussed later, it is likely that the

choices. Four additional items were appended but were not respondents constituted a mentally healthier subset of the

used for most analyses. Development of the CES-D, its student enrollment.

validation with adults, and its use with community and Among the 504 subjects interviewed, females tended to

national samples have been described. 14.17.18 Use of the scale be somewhat younger than males. White males (WM) were

with adolescents has not been reported by others. underrepresented in seventh grade. Substantial proportions

The response choices used for this study ("Rarely or of subjects were not living with both natural parents. Fully

None of the Time," "Some or a little of the time," "A Lot of half of White subjects but only 6 per cent of Black subjects

the time," or "Most or all of the time"), like those in the came from homes in which at least one natural parent had

standard form of the CES-D, refer to the duration or four or more years of school beyond high school. Half of the

frequency of recurrence of the symptom during the past Blacks and only 12 per cent of the Whites came from homes

week. Although subject responses are usually combined into in which neither natural parent had completed high school.

a single score based on response values of zero through three Virtually the same statements could be made about the 384

with three being the maximally depressive response, Craig subjects with satisfactory depressive symptom data (Table

and Van Natta'9.20 have argued that overall scores disregard 2). These dramatic differences in the socioeconomic levels of

the different clinical significance of persistent and transient the White and Black students reflect the marked race-linked

symptoms. Therefore the present study has examined the socioeconomic differences in the school's enrollment, rein-

item responses themselves and compared both "persistent" forced by the apparently higher refusal rate in middle class

and "present" symptoms across groups. For the 16 negative households of both races.

items in the 20-item CES-D, "'persistent" refers to the Internal consistency of CES-D responses was generally

response "Most or all of the time." For the four positive adequate. Item-scale Spearman correlations were above .50

items, "persistent" refers to the response "Rarely or none for most items and above .40 for all but three. Values of

1 282 AJPH November 1983, Vol. 73, No. 11

SELF-REPORTED DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS IN ADOLESCENTS

TABLE 2-Percentage Distribution of Sociodemographic Characteristics and .85 overall. This result is virtually identical to the value

of 384 Subjects with Satisfactory Depressive Symptom Data of .85 reported by Radlofft4 for White adults in community

surveys.

% Whites % Blacks Selected item-pairs* thought likely to be highly correlat-

Characteristics (N = 253) (N = 131)

ed were identified in advance of the data analysis. Spearman

Gender (N = 253) (N = 131) correlation coefficients for pairs of items of like polarity

Male 46 45 ranged from .21 to .57 (median = .39), and all were signifi-

Female 54 55 cant, with p < .001. Coefficients for pairs of opposite items

Age last birthday (years) (N = 253) (N = 131) ranged from -.09 to -.34 (median = .24), with a p < .05 for

12* 24 30

13 36 31 all pairs, p < .001 for all but two. Weighted Kappas22 with

14 34 30 linear disagreement weights ranged from .19 to .49 (median

15** 6 10 .30) for pairs of items of like polarity; Kappas for pairs of a

Grade in school (N = 253) (N = 131) negative item with the inverted response value of a positive

7 29 39

8 34 35 item were lower (.07 to .22, median .15).

9 37 26 Symptom Frequencies

Natural parents in subject's household (N = 250) (N = 129)

Both parents 67 31 Table 3 displays the response distributions for the entire

Father only 6 5 sample for each CES-D item. The general pattern is consist-

Mother only 27 64 ent with that expected for a healthy population. A majority

(Father deceased) 4 13 of respondents checked "Rarely" for the negative items.

Parental educationt (N = 241) (N = 106)

Less than 12 yrs 10 47 The distribution for most items descends rapidly toward the

12-15 yrs 37 47 more depressive responses, with "Most" chosen by fewer

16 yrs or more 53 6 than 12 per cent of respondents for any item. For the positive

Household incomett (N = 198) (N = 80)

Less than $6,000 5 55 items, the distributions are flatter, with somewhat larger

$6,000-$1 5,000 21 36 percentages reporting the most depressive response ("Rare-

$15,000-$25,000 26 9 ly"). Response distributions for WM and WF correspond

More than $25,000 48 0 closely to the aggregate distributions. Those for BM and BF

are similar but have higher percentages of depressive re-

*Includes 1 11-year-old female.

-Includes 4 16-year-old males. sponses.**

tNumber of years of school completed by natural parent living at home; if both natural "Persistent" symptoms were for the most part equally

parents lived with the subject, then the higher value was used. [Subject's report, unless only rare for WM and WF, but more frequent among Blacks,

a parent's report was available.]

ttlncome from all sources, including governmental assistance, as reported on the

parental questionnaire (1978 dollars). *AIl pairs from among the items "I felt that I could not shake off the blues

. ." (3), "I felt depressed" (6), "I thought that my life had been a failure"

(9), "I felt sad" (18), "I felt that I was just as good as other people" (4), "I

Cronbach's coefficient alpha2l calculated for the 270 subjects was happy" (12), "I enjoyed life" (16), "I felt great" (24). This was the only

who answered every item were above .80 in each race-sex analysis that included one of the items appended to the CES-D ("I felt great"

[24]).

group (.83, .83, .89, .86 for WM, WF, BM and BF, respec- **Race-sex specific response percentages for all items are available from

tively, based on 92, 109, 25, and 44 subjects, respectively) the first author on request.

TABLE 3-Distributions of Responses to Items In CES-Depression Scale, Entire Sample

Rarely or Some or A A Lot of

None of the Little of the the Most or All

Time Time Time of the Time

(0) (1) (2) (3)

-Item % % % % N

Bothered by things 42 44 11 4 379

Not feel like eating 56 30 10 4 377

Could not shake blues 50 34 12 4 373

Just as good as others* 12 28 32 29 375

Trouble keeping mind on things 31 40 22 8 376

Felt depressed 45 37 13 6 360

Everything was an effort 25 38 25 11 372

Hopeful about the future* 15 26 34 25 366

Life had been a failure 66 24 6 4 376

Felt fearful 54 31 10 5 376

Sleep was restless 53 26 15 6 370

Was happy* 9 19 36 36 377

Talked less than usual 40 35 16 9 372

Felt lonely 53 31 10 6 376

People were unfriendly 52 31 13 5 368

Enjoyed life* 11 17 32 40 370

Had crying spells 69 17 10 5 373

Felt sad 53 32 11 5 374

Felt people disliked me 53 31 10 6 375

Could not get going 48 33 11 7 374

Note: * indicates a positive item.

AJPH November 1983, Vol. 73, No. 11 1283

SCHOENBACH, ET AL.

TABLE 4-Symptom Persistence (Per Cent of Subjects Reporting Symptoms at Level Three)

White Black White Black All

Males Males Females Females Groups

Item % % % %

Bothered by things 3 0 2 11 4

Not feel like eating 2 2 4 9 4

Could not shake blues 3 7 4 4 4

Just as good as others* 11 10 10 17 12

Trouble keeping mind on things 5 7 8 14 8

Felt depressed 5 2 5 9 6

Everything was an effort 11 11 11 13 11

Hopeful about the future* 15 21 13 15 15

Life had been a failure 2 13 2 4 4

Felt fearful 4 11 2 6 5

Sleep was restless 6 14 3 7 6

Was happy* 7 18 5 11 9

Talked less than usual 6 20 4 17 9

Felt lonely 7 14 2 6 6

People were unfriendly 5 5 4 4 5

Enjoyed life* 5 17 8 19 11

Had crying spells 2 9 5 4 5

Felt sad 1 4 7 6 5

Felt people disliked me 4 9 6 6 6

Could not get going 3 14 5 13 7

Minimum number of subjects (110) (51) (131) (64) (360)

Note: *indicates that response values have been reversed.

especially BM (Table 4). The racial difference in percentages ty, Maryland and Kansas City, Missouri. The surveys have

reporting "persistent" symptoms is substantial. For symp- been reported by Comstock and Helsing'5 and Radloff. 14 For

toms reported as "present" (Table 5), the racial difference, reasons of space, the percentages for males and females

particularly among females, is attenuated, and a female have been averaged with equal weighting. The summariza-

excess exists among Whites (among Blacks there is a slight tion conceals sex differences in symptom prevalence among

male excess). Moreover, there is a strong correspondence adults and adolescents, particularly for some "present"

across race-sex groups, in that symptoms reported relatively symptoms and sex-related behaviors, such as crying. In

more often by one group tend to be reported more often by Whites, persistent symptoms (Table 6) are neither consis-

other groups. tently more nor consistently less frequent in the young

Comparison of the CES-D responses of the young adolescents than in the adults. The adolescents are less apt

adolescents with those of adults was carried out using to report persistent vegetative symptoms (loss of appetite,

previously unpublished data collected during the first wave restless sleep, could not get going) and more apt to report

of interviews from community surveys in Washington Coun- symptoms with a developmental connotation (not just as

TABLE 5-Symptom Presence (Per Cent of Subjects Reporting Symptoms at Level One, Two, or Three)

White Black White Black All

Males Males Females Females Groups

Item % % % % %

Bothered by things 44 61 63 69 58

Not feel like eating 30 55 46 51 44

Could not shake blues 36 56 56 56 50

Just as good as others* 68 71 75 68 71

Trouble keeping mind on things 62 71 78 64 69

Felt depressed 45 58 59 63 55

Everything was an effort 76 80 72 72 75

Hopeful about the future* 68 85 76 74 75

Life had been a failure 19 51 34 46 34

Felt fearful 34 52 44 64 46

Sleep was restless 37 52 46 63 47

Was happy* 60 79 57 73 64

Talked less than usual 50 78 57 69 60

Felt lonely 38 66 47 46 47

People were unfriendly 49 51 48 46 48

Enjoyed life* 53 75 58 64 60

Had crying spells 18 41 37 35 31

Felt sad 39 59 51 42 47

Felt people disliked me 39 55 52 43 47

Could not get going 45 59 56 49 52

Minimum number of subjects (110) (51) (131) (64) (360)

Note: *indicates that response values have been reversed.

1 284 AJPH November 1983, Vol. 73, No. 11

SELF-REPORTED DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS IN ADOLESCENTS

TABLE 6-Symptom Persistence in Young Adolescents and Community Adults (Per Cent of Subjects Reporting Symptoms at Level Three)

Whites Blacks

Community

Community Adults Adults

Young Young

Adolescents 18-24 25-64 65+ Adolescents 25-64 only

Bothered by things 2 4 5 6 6 10

Not feel like eating 3 9 6 9 5 13

Could not shake blues 4 5 4 5 6 5

Just as good as others* 11 5 9 9 14 6

Trouble keeping mind on things 7 14 7 6 11 5

Felt depressed 5 7 5 7 6 10

Everything was an effort 11 18 16 17 12 22

Hopeful about the future* 14 11 15 24 18 22

Life had been a failure 2 3 2 2 9 4

Felt fearful 3 3 2 2 8 3

Sleep was restless 5 12 11 14 11 9

Was happy* 6 3 6 8 15 10

Talked less than usual 5 7 4 4 18 6

Felt lonely 5 4 4 8 10 9

People were unfriendly 5 3 2 1 5 4

Enjoyed life* 7 4 6 8 18 6

Had crying spells 4 2 1 1 7 0

Felt sad 4 3 3 5 5 4

Felt people disliked me 5 2 1 1 7 4

Could not get going 4 8 7 9 14 6

Minimum number of subjects (110) (144) (707) (146) (51) (93)

Note: *indicates that response values have been reversed.

Source: Adult data from Washington County, Md., and Kansas City, Mo., community surveys ;kindly provided by Lenore Sawyer Radloff, Center for Epidemiologic Studies (NIMH). The

surveys are described in Radloff14.

good, fearful, others unfriendly, disliked, crying). Among responses (although response tendencies could elevate such

Blacks, most symptoms are reported as persistent more consistency). The variation in response frequencies across

often by the adolescents, with a few marked exceptions items, the correspondence across race-sex groups, and the

(Table 6). For "present" symptoms (Table 7), the adolescent systematic differences between groups all suggest that the

percentages exceed those among adults, often dramatically, adolescents were responding in a serious manner. "Persist-

in all race-sex groups and for nearly all items. ent" symptoms were relatively uncommon among the ado-

Discussion lescents, the prevalence in the Whites being no greater than

that reported for adults. Persistent symptoms were reported

Interpretation of the data presented above should take equally often by White male and White female adolescents,

into account the large numbers of nonparticipants (120 of whereas the latter reported "present" symptoms more of-

624) and of skipped or inadequately completed depressive ten. A similar pattern has been observed in adults.20 The

symptom scales (120 of 504), particularly for the Black high rates of "present" symptoms among the adolescents, if

males. The likelihood that reading difficulties and lower not a peculiarity of this study population, would extend

socioecc nomic status were associated with failure to com- Craig and Van Natta's observation that the reporting of

plete the symptom scale would probably lead to underreport- "present" symptoms declines with age.20

ing of symptom prevalence, in view of Rutter, et al's report Thus, in a number of regards, the adolescents' CES-D

of an association between reading difficulties and persistent responses are a plausible measure of depressive symptom

psychiatric disorder2 as well as the many reports'52324 of prevalence. The different relationship to age of reported

associations between depressive symptoms and lower socio- "persistent" and "present" symptoms may reflect the influ-

economic status. The data for White females are presumably ence of developmental factors on emotional experience or on

least affected. reporting, possibly jeopardizing comparability of CES-D

It is more difficult to judge the impact of the refusals, scores across age groups. Future studies of depressive

particularly since the study was principally concerned with symptoms should attempt to distinguish transient and non-

adolescent sexual attitudes and behavior rather than with transient symptoms.

depression. Undersampling of middle class households prob- A possible implication of the present data is that if, as

ably overstates symptom prevalence. Of likely greater im- suggested by Kovacs and Beck,4 depressive disorders in

portance, though, is the unusual nature of the school's children and adolescents have similar manifestations to their

enrollment, with its high proportion of well-to-do families adult expression, and if, as suggested by Craig and Van

and exaggerated socioeconomic disparity between Whites Natta,'9 reported persistent depressive symptoms are more

and Blacks. The disparity could well have affected the indicative of clinical depression than are transient symp-

emotional experience of the students, especially of the toms, then clinical depression is probably not more common

poorer ones. Therefore generalizability of the actual preva- in early adolescence than in adults. Our attempt to interpret

lences presented above is uncertain. CES-D responses in such a way as to identify a depressive

With regard to the measurement question, the analyses syndrome along the lines of the Research Diagnostic Crite-

of internal consistency support the reliability of the symptom ria25 for major depressive disorder yielded an estimated

AJPH November 1983, Vol. 73, No. 11 1 285

SCHOENBACH, ET AL.

TABLE 7-Symptom Presence in Young Adolescents and Community Adults (Per Cent of Subjects Reporting Symptoms at Level One, Two, or Three)

Whites Blacks

Community

Community Adults Adults

Young Young

Adolescents 18-24 25-64 65+ Adolescents 25-64 only

Bothered by things 54 45 38 23 65 33

Not feel like eating 38 35 22 23 53 31

Could not shake blues 46 36 20 14 56 26

Just as good as others* 72 30 19 13 70 14

Trouble keeping mind on things 70 60 39 26 68 35

Felt depressed 52 50 35 21 60 41

Everything was an effort 74 62 44 37 76 46

Hopeful about the future* 72 44 37 37 80 38

Life had been a failure 26 14 11 8 49 15

Felt fearful 39 29 15 10 58 18

Sleep was restless 42 52 42 42 57 39

Was happy* 59 35 29 26 76 37

Talked less than usual 54 42 24 16 74 36

Felt lonely 42 39 21 24 56 30

People were unfriendly 48 25 12 6 49 21

Enjoyed life* 55 29 20 20 69 25

Had crying spells 28 16 9 7 38 9

Felt sad 45 45 27 23 50 33

Felt people disliked me 46 25 10 6 49 18

Could not get going 50 53 39 28 54 30

Minimum number of subjects (110) (144) (707) (146) (51) (93)

Note: Indicates that response values have been reversed.

Source: Adult data from Washington County, Md., and Kansas City, Mo., community surveys kindly provided by Lenore Sawyer Radloff, Center for Epidemiologic Studies (NIMH). The

surveys are described in Radloff14.

prevalence of 2.9 per cent.26 The few other published junior high school studied is located in a White neighbor-

reports27,28 on population prevalence of depressive disorder hood, with the Black students being bused in from else-

in young adolescents yield similar figures, although these where. Rosenberg has reported lower self-esteem ratings for

estimates are also derived from small numbers of affected adolescents in such "dissonant contexts."3' It is possible

youngsters. A 1948 statewide sample of Minnesota ninth- that the Black males may have borne the brunt of racial

graders29 detected Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inven- antagonism, which could account for their high symptom

tory profiles suggestive of clinical depression in 4 per cent of rates.

boys and 1.5 per cent of girls. In contrast, reporting of In summary, we have presented evidence that persistent

symptoms per se was much more frequent, both in our study depressive symptoms in young adolescents appear to be

and in others. ' 2 measurable and meaningful. Future research is needed to

The high rate of missing data and likely reading difficul- validate and refine measures of depressive symptoms and

ties among the Black males call for a conservative interpreta- their correlates, to assess duration and recurrence through

tion of their apparent high symptom prevalence. This high longitudinal observation, to ascertain behavioral conse-

prevalence is broadly consistent, however, with the findings quences, and to identify modifiable factors that contribute to

of higher depressive symptom prevalence in Black the experience of persistent or recurrent symptoms. A

adults,'52324'30although the relative ranking of males and particularly salient question is the relationship of reported

females has varied. In general, the racial difference in adults symptoms to subsequent suicide attempts or involvement in

has been attributed to socioeconomic differences, in that it other hazardous behaviors. Preventive and supportive inter-

was eliminated by adjustment for income and/or education. ventions might include modification of school, home, and

In one case,24 adjustment eliminated the significant racial community environments to reduce conflicting or untimely

difference in mean CES-D scores but not in the prevalence of demands, instruction in coping skills,32 and provision of

high CES-D scores. Since Blacks below the poverty line had additional supports especially for high-risk groups.

the highest adjusted rate for any group in that study, not all

of the high depressive symptom prevalence could be ac-

counted for by reported income itself.24 REFERENCES

Our data do not permit us to distinguish between the 1. Albert N, Beck AT: Incidence of depression in early adolescence: a

relative importance of race and socioeconomic status varia- preliminary study. J Youth Adol 1975; 4:301-306.

bles, because of insufficient overlap between the socioeco- 2. Rutter M, Graham P, Chadwick OFD, Yule W: Adolescent turmoil: fact

or fiction? J Child Psychol Psychiat 1976; 17:35-56.

nomic backgrounds of the two racial groups. Since the 3. Akiskal HS, McKinney WT Jr: Overview of recent research in depres-

majority of the Black students in the present study came sion. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1975; 32:285-305.

from households with 1978 income less than $6,000 and in 4. Kovacs M, Beck AT: An empirical-clinical approach toward a definition

which no natural parent had 12 years of schooling, socioeco- of childhood depression. In: Schulterbrandt JG and Raskin A (eds):

nomic depreviation is a prime suspect either alone or by Depression in Childhood. New York: Raven, 1977, pp 1-25.

5. Leighton AH: Psychiatric disorder and social environment. In: Kaplan

contrast to the relative affluence of the White students. BH (ed): Psychiatric Disorder and the Urban Environment. New York:

Other factors could also be involved. For example, the Behavioral Publications, 1971, pp 20-67.

1 286 AJPH November 1983, Vol. 73, No. 11

SELF-REPORTED DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS IN ADOLESCENTS

6. Conners CK: Classification and treatment of childhood depression and 23. Warheit GJ, Holzer CE, Schwab JJ: An analysis of social class and racial

depressive equivalents. In: Gallant DM and Simpson GM (eds): Depres- differences in depressive symptomatology: a community study. J Health

sion: Behavioral, Biochemical, Diagnostic and Treatment Concepts. New & Social Behavior 1973; 14:291-299.

York: Spectrum, 1976, pp 181-204. 24. Eaton WE, Kessler LG: Rates of symptoms of depression in a national

7. Graham P: Depression in pre-pubertal children. Develop Med Child sample. Am J Epidemiol 1981; 114:528-538.

Neurol 1974; 16:340-349. 25. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E: Research diagnostic criteria: rationale

8. Lefkowitz MM, Burton N: Childhood depression: a critique of the and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978; 35:773-782.

concept. Psychological Bulletin 1978; 85:716-726. 26. Schoenbach VJ, Kaplan BH, Grimson RC, Wagner EH: Use of a

9. Hamburg BA: Early adolescence: a specific and stressful stage of the life symptom scale to study the prevalence of a depressive syndrome in young

cycle. In: Coelho GV, Hamburg DA, and Adams JE (eds): Coping and adolescents. Am J Epidemiol 1982; 116:791-800.

Adaptation. New York: Basic Books, 1974, pp 101-124. 27. Leslie SA: Psychiatric disorder in the young adolescents of an industrial

10. Hays SE: Strategies of psychoendocrine studies of puberty. Psychoneur- town. Brit J Psychiat 1974; 125:113-124.

oendocrinology 1978; 3:1-15. 28. Kashani J, Simonds JF: The incidence of depression in children. Am J

11. Lipsitz J: Growing up Forgotten: A Review of Research and Programs Psychiatry 1979; 136:1203-1204.

Concerning Early Adolescence. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1977. 29. Hathaway SR, Monachesi ED: Adolescent personality and behavior.

12. Bauman KE, Udry JR: Subjective expected utility and adolescent sexual Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1963.

behavior. Adolescence 1981; 16:527-535. 30. Frerichs RR, Aneshensel CS, Clark VA: Prevalence of depression in Los

13. Morris NM, Udry JR: Validation of a self-administered instrument to Angeles County. Am J Epidemiol 1981; 113:691-699.

assess stage of adolescent development. J Youth Adol 1980; 9:271-280. 31. Rosenberg M: Dissonant context and adolescent self-concept. In: Dragas-

14. Radloff LS: The CES-D scale: a self-repprt depression scale for research tin SE and Elder GH (eds): Adolescence in the life cycle. New York:

in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1977; Wiley, 1975.

1:385-401. 32. Hamburg DA, Adams JE, Brodie HKH: Coping behavior in stressful

15. Comstock GW, Helsing KJ: Symptoms of depression in two communi- circumstances: some implications for social psychiatry. In: Kaplan BH,

ties. Psychological Med 1976; 6:551-563. Wilson RN, Leighton AH (eds): Further explorations in social psychiatry.

16. Sayetta RB, Johnson DP: Basic data on depressive symptomatology, New York: Basic Books, 1976, pp 158-175.

United States, 1974-75. US Department of Health, Education, and

Welfare, Public Health Service, National Center for Health Statistics,

Series I 1, Number 216, (DHEW Pub. [PHS] 80-1666), 1980. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

17. Weissman MM, Sholomskas D, Pottenger M, Prusoff BA, Locke BZ: The authors wish to express their appreciation to J. Richard Udry, PhD,

Assessing depressive symptoms in five psychiatric populations: a valida- and Karl E. Bauman, PhD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

tion study. Am J Epidemiol 1977; 106:203-214. for collecting the data reported in this paper as part of their research on

18. Hankin JR, Locke BZ: The persistence of depressive symptomatology adolescent sexual behavior. Lenore S. Radloff of the Center for Epidemiolog-

among prepaid group practice enrollees: an exploratory study. Am J ic Studies, National Institute of Mental Health, provided helpful consultations

Public Health 1982; 72:1000-1007. and kindly made available previously unpublished data from the Center for

19. Craig TJ, Van Natta PA: Presence and persistence of depressive symp- Epidemiologic Studies' community survey in Washington County, Maryland

toms in patient and community populations. Am J Psychiatry 1976; and Kansas City, Missouri. Ralph C. Patrick, PhD, Martha L. Smith, Marion

133:1426-1429. E. Schoenbach, MSPH, Sherman A. James, PhD, and Dr. Udry provided

20. Craig TJ, Van Natta PA: Influence of demographic characteristics on two consultation and assistance throughout the project. We are also grateful to

measures of depressive symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979; 36:149- Michel A. Ibrahim, MD, PhD, for helpful editorial suggestions and to Patricia

154. G. Taylor for typing the manuscript through its various drafts. Dr. Schoen-

21. Nunnally JC: Psychometric Thoery. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1967. bach was supported by Public Health Service Traineeships from the National

22. Cohen J: Weighted kappa: nominal scale agreement with provision for Institute of Mental Health, under grant MH 13661. Data collection was

scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychological Bulletin 1968; 70:213- supported by grant No. ROI-HD12806-01 from the National Institute of Child

220. and Human Development to the Carolina Population Center.

I ERRATUM I

In: Landrigan PJ, Powell KE, James LM, Taylor PR: Paraquat and marijuana: epidemiologic risk

assessment. Am J Public Health 1983; 73:784-788.

In the footnote on page 784, column 1, the statement says "This paper, submitted to the Journal

September 30, 1983, was revised and accepted for publication February 1, 1983." The date of

submission was September 30, 1982-not 1983.

AJPH November 1983, Vol. 73, No. 11 1287

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Basic Factors of Delivery (Chuy)Document8 pagesBasic Factors of Delivery (Chuy)Joselyn TasilNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- IPPDDocument3 pagesIPPDRussell Mae MilanNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Zeta Tau Alpha BrochureDocument2 pagesZeta Tau Alpha Brochureapi-281027266No ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Research Paper On Emerging Trends in HRMDocument5 pagesResearch Paper On Emerging Trends in HRMefdwvgt4100% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Language Choices and Pedagogic Functions in The Foreign Language Classroom: A Cross-Linguistic Functional Analysis of Teacher TalkDocument26 pagesLanguage Choices and Pedagogic Functions in The Foreign Language Classroom: A Cross-Linguistic Functional Analysis of Teacher TalkChloe WangNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- DNP Essentials EportfolioDocument3 pagesDNP Essentials Eportfolioapi-246869268100% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- M3. 1. PT - Story Telling Technique PDFDocument56 pagesM3. 1. PT - Story Telling Technique PDFShams JhugrooNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- EF4e Adv Plus TG PCM Grammar 4ADocument1 pageEF4e Adv Plus TG PCM Grammar 4AWikiUp MonteriaNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Topic Approval Form With Evaluation Questions 2017-2018Document1 pageTopic Approval Form With Evaluation Questions 2017-2018api-371221174No ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Narrative On Parents-Teachers Orientation 22-23Document3 pagesNarrative On Parents-Teachers Orientation 22-23Giselle Sadural CariñoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 Moral ReasoningDocument16 pagesChapter 4 Moral Reasoningcrystalrosendo7No ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesArnold Leand BatulNo ratings yet

- BM564 PR1 Assignment Brief 31.03Document5 pagesBM564 PR1 Assignment Brief 31.03constantin timplarNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Management As An ArtDocument8 pagesManagement As An Artgayathri12323No ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Arithmetic SequencesDocument3 pagesArithmetic SequencesAnonymous IAJD0fQ82% (11)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Exam Day Flyer 2023 DocumentDocument24 pagesExam Day Flyer 2023 DocumentMarisa NogozNo ratings yet

- CSR Executive Summary DLF - Udit KhanijowDocument3 pagesCSR Executive Summary DLF - Udit KhanijowUdit Khanijow0% (1)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Electrical and Chemical Diagnostics of Transformer Insulation Abstrac1Document36 pagesElectrical and Chemical Diagnostics of Transformer Insulation Abstrac1GoliBharggavNo ratings yet

- Chapter 02Document20 pagesChapter 02jeremyNo ratings yet

- Ethnographic IDEODocument5 pagesEthnographic IDEORodrigo NajjarNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Study Guide (ITIL 4 Foundation) .PDF Versión 1 (27-44)Document18 pagesStudy Guide (ITIL 4 Foundation) .PDF Versión 1 (27-44)Brayhan Huaman BerruNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Ma. Georgina Belen A. Guevara 27 San Mateo St. Kapitolyo, Pasig City 576-4687 / 0927-317-8221Document4 pagesMa. Georgina Belen A. Guevara 27 San Mateo St. Kapitolyo, Pasig City 576-4687 / 0927-317-8221Colette Marie PerezNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Computer Technology Timeline ProjectDocument2 pagesEvolution of Computer Technology Timeline Projectapi-309498815No ratings yet

- FMA Vol6 No4Document67 pagesFMA Vol6 No4laukuneNo ratings yet

- Used Strategies For Providing Timely, Accurate and Constructive Feedback To Improve Learner PerformanceDocument17 pagesUsed Strategies For Providing Timely, Accurate and Constructive Feedback To Improve Learner PerformancemaristellaNo ratings yet

- Linux - 100 Flavours and CountingDocument3 pagesLinux - 100 Flavours and CountingMayank Vilas SankheNo ratings yet

- Form 3 Booklist - 2021 - 2022Document3 pagesForm 3 Booklist - 2021 - 2022Shamena HoseinNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- A Twin Study of Graphology Judith Faust and John Price 1972Document18 pagesA Twin Study of Graphology Judith Faust and John Price 1972Carlos AguilarNo ratings yet

- ScreenDocument3 pagesScreenAdrian BagayanNo ratings yet

- Local Literature Thesis WritingDocument7 pagesLocal Literature Thesis Writingzyxnlmikd100% (1)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)