Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Assessment - The Bridge Between Teaching and Learning (VFTM 2013)

Uploaded by

Luis CYOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Assessment - The Bridge Between Teaching and Learning (VFTM 2013)

Uploaded by

Luis CYCopyright:

Available Formats

Dylan

Wiliam | Assessment: The Wiliam

Bridge between Teaching and Learning

page

15

Assessment: The Bridge between

Teaching and Learning

O

ur students do not learn what dents and teachers, while others also see interim,

we teach. It is this simple and or benchmark, tests administered every six to ten

weeks as formative. For my part, I believe that

profound reality that means

any assessment can, potentially, be formative,

that assessment is perhaps the central which is why I suggest that to describe an assess-

process in effective instruction. If our ment as formative is what Gilbert Ryle (1949) de-

students learned what we taught, we scribed as a “category mistake” (p. 16; ascribing

would never need to assess. We could to something a property it cannot have).

The term formative should apply not to the

simply catalog all the learning experiences assessment but to the function that the evidence

we had organized for them, certain in generated by the assessment actually serves. For

the knowledge that this is what they had example, a seventh-grade teacher had given her

learned. students an English language arts test, under test

conditions, and collected the students’ test re-

But of course, anyone who has spent more than a sponses. Most teachers would then try to grade

few hours in a classroom knows this hardly ever the students’ responses, add helpful feedback,

happens. No matter how carefully we design and and return the graded papers to the students the

implement the instruction, what our students following day. On this occasion, however, the

learn cannot be predicted with any certainty. It teacher did not grade the papers. She quickly

is only through assessment that we can discover read through them and decided that the follow-

whether the instructional activities in which we ing day each student would receive back her or

engaged our students resulted in the intended his own paper; in addition, groups of four stu-

learning. Assessment really is the bridge between dents would be formed, and each group would

teaching and learning. be given one blank response sheet, so that they

could, as a group, produce the best composite pa-

Formative Assessment per. When the groups had done this, the teacher

led a plenary discussion in which groups reported

Of course, the idea that assessment can help

back their agreed responses. What is interesting

learning is not new, but what is new is a growing

about the example is that the assessment being

body of evidence that suggests that attention to

used had been designed entirely for summative

what is sometimes called formative assessment, or

purposes, but the teacher had found a way of us-

assessment for learning, is one of the most pow-

ing it formatively.

erful ways of improving student achievement.

If we accept that any assessment can be used

Different people have different views about what

formatively, we need some way of defining for-

exactly counts as formative assessment. Some

mative assessment in a way that is useful for class-

think it should be applied only to the minute-to-

room practice. The way that I have found most

minute and day-to-day interactions between stu-

useful is to think of three key processes in learning:

Voices from the Middle, Volume 21 Number 2, December 2013

Wiliam | Assessment: The Bridge between Teaching and Learning

page

16 1. Where the learner is right now good, we should do so, but we should also re-

2. Where the learner needs to be member Albert Einstein’s advice: “Make things

as simple as possible, but no simpler.” Some-

3. How to get there

times, we should accept that the best we can do is

It’s also vital to consider the respective roles help our students develop what Guy Claxton has

of teachers, students, and their peers. Regarding called “a ‘nose’ for quality” (1995, p. 00). Indeed,

the processes and the roles as independent (so some writers, such as Royce Sadler (1989), have

that teachers, students, and peers have a role in argued that this is an essential precondition for

each) suggests that formative assessment can be learning:

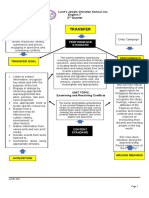

thought of as comprising five “key strategies” as The indispensable conditions for improvement are

shown in Figure 1.1 Each of the five strategies is that the student comes to hold a concept of quality

discussed in further detail in the sections that fol- roughly similar to that held by the teacher, is able

low. to monitor continuously the quality of what is being

produced during the act of production itself, and has

a repertoire of alternative moves or strategies from

Key Strategies of Formative which to draw at any given point. (p. 121)

Assessment

In recent years, it has been common for writ-

Learning Intentions ers to advocate the “co-construction” of rubrics

The idea that teachers should share with their with students. The idea is that rather than having

students what it is intended that they learn from the teacher present the students with a rubric as

a given instructional activity seems obvious, but “tablets of stone,” the rubric is developed with the

it is only within the past 20 years or so that this students. A common method for doing this is for

has been routine in English language arts class- the teacher to provide the students with a num-

rooms. While this is a welcome development, it ber of samples of work of varying quality (e.g.,

is also important to note that in many schools, anonymous samples from a previous year’s class);

well-intentioned attempts to communicate learn- the students then rank them and begin to iden-

ing intentions to students have made writing a tify features that distinguish the stronger work

mechanistic process of checklist management. from the weaker work. This can be a very power-

It is true that rubrics can identify important ele- ful process, but the end point of such a process

ments of progression in writing, but they can too must reflect the teacher’s concept of quality. The

easily become a straitjacket. To be sure, where teacher knows what quality writing looks like;

we can, with fidelity, specify what makes writing students generally do not. Of course, the teach-

er’s views of quality work may shift in discussion

Where the Where the learner is How to get there with a class, but the teacher is already immersed

learner is going right now in the discipline of English language arts and the

students are just beginning that journey.

Engineering effective

Feedback that

discussions, activities,

Teacher

and tasks that elicit

moves learning Eliciting Evidence

forward

Clarifying, evidence of learning Although feedback is considered by many to be

sharing, and the heart of formative assessment, it turns out that

understanding Activating students as learning resources the quality of the feedback hinges on the qual-

Peer learning inten- for one another ity of evidence that is elicited in the first place.

tions

Knowing that a student has scored only 30% on

Activating students as owners of their a test says nothing about that student’s learning

Student needs, other than that he or she has apparently

own learning

failed to learn most of what was expected. The

Figure 1. The five “key strategies” of formative assessment

Voices from the Middle, Volume 21 Number 2, December 2013

Wiliam | Assessment: The Bridge between Teaching and Learning

page

point is, effective feedback requires asking the On an even shorter time-scale, a fifth-grade 17

right questions. This may be obvious, but what is teacher had been introducing students to five

less obvious is that effective feedback requires a kinds of figurative language: alliteration, hyper-

plan of action about what to do with the evidence bole, onomatopoeia, personification, and simile.

before it is collected. Five minutes before the end of the lesson, she

Many schools and districts espouse a com- listed the five kinds

quote

mitment to data-driven decision making, but too of figurative language

often, this entails the collection of large bodies of on the whiteboard.

data just in case they come in useful at some later She then read out a

point. This is a particular problem when teachers series of sentences,

administer common formative assessments to all asking the students to

students in a grade and then meet to discuss what use “finger voting” to

to do. By the time all the common assessments indicate what kinds of

have been graded and a meeting to discuss the figurative language they had heard (e.g., hold up

implications has been scheduled, the data are well one finger if you hear alliteration, five fingers if

past their “sell-by” date; the teaching has moved you hear a simile, and so on).

on. And even if the data were available in a timely These are the sentences she read out:

fashion, unless time has already been scheduled

A. He was like a bull in a china shop.

for any additional instruction shown to be nec-

essary by the assessments, nothing useful can B. This backpack weighs a ton.

happen. That is why data-driven decision mak- C. The sweetly smiling sunshine warmed

ing is not a particularly helpful approach. What the grass.

is needed instead is a commitment to decision- D. He honked his horn at the cyclist.

driven data collection. For example, rather than

E. He was as tall as a house.

an “end of unit test,” the teacher could sched-

ule a “three-fourths of the way through the unit Most of the students responded correctly to

test.” Rather than grading the papers, the teacher the first two, but most of them chose to hold up

could use the information gleaned from the test either one finger or four fingers for the third.

to decide which aspects of the unit need to be The teacher pointed out to the class that a few

re-taught or, if the students have all done well, students had held up one finger on one hand and

provide some extension material. four on the other, because the sentence was an

CONNECTIONS FROM READWRITETHINK

Knowledge into Action: Figurative Language

One way to assess students’ understanding is to put their knowledge into action. The article shares an example using

the study of figurative language. The ReadWriteThink.org lesson plan “Figurative Language Awards Ceremony” invites

students to explore books rich in figurative language and nominate their favorite examples of similes, metaphors, and

personification for a figurative language award. Once nominations are in, the class votes, selecting a winning example

in each category. Finally, students are challenged to write an acceptance speech for one of the winners, using as many

literary devices (simile, metaphor, personification) as they can in their speech.

Lisa Fink

www.readwritethink.org

Voices from the Middle, Volume 21 Number 2, December 2013

Wiliam | Assessment: The Bridge between Teaching and Learning

page

18 example of both alliteration and personification, feedback is best?” is meaningless, because while

while most students had assumed that a sentence a particular kind of feedback might make one

quote could only have one kind student work harder, it might cause another stu-

of figurative language. dent to give up. There can be no simple recipe

With this misconcep- for effective feedback; there is just no substitute

tion cleared up, most for the teacher knowing their students. Why?

of the students realized First, knowing the students allows the teacher

that the fourth state- to make better judgments about when to push

ment was both allitera- each student and when to back off. Second, when

tion and onomatopoeia students trust the teacher, they are more likely

while the last was both a to accept the feedback and act on it. Ultimately,

simile and hyperbole. the only effective feedback is that which is acted

The important point about this example is upon, so that feedback should be more work for

that the teacher planned to collect the data only the recipient than the donor.

once she had decided how she was going to use

it—in this case managing to administer, grade, Students as Learning Resources for

and take follow-up remedial action in less than One Another

three minutes. There is a large body of literature on peer tu-

toring and collaborative learning—particularly

Feedback in English language arts—that it is neither pos-

In 1996, two researchers in the psychology de- sible nor necessary to review here (e.g., Brown &

partment at Rutgers University published an Campione, 1995 [reciprocal instruction]; Slavin,

extraordinary review of research studies on the Hurley, & Chamberlain, 2003 [general models

effects of feedback in schools, colleges, and work- of collaborative learning]). However, it is worth

places (Kluger & DeNisi, 1996). They began by noting that peers can be very effective assessors

tracking down a copy of every single published of one another’s work, especially when the fo-

study on feedback they could find, going back to cus is on improvement rather than grading. One

1905! They found around 3,000 (2,500 journal sixth-grade class was working on suspense sto-

articles and 500 technical reports). They then an- ries, and the teacher had co-constructed with the

alyzed the studies to see whether the conclusions students a checklist of four key phases that made

could be trusted. They eliminated those without a a good suspense story: establishment, build-up,

control group that was not given feedback, those climax, and resolution. The class also decided

for which the effects could not be attributed only that it would be a good idea, just as an exercise if

to the feedback given, and those for which there nothing else, for the story to contain at least two

was not sufficient detail to quantify the impact of examples of figurative language.

feedback on achievement. They were surprised The students worked on their stories and,

to discover that only 131 studies made the cut. when everyone was done, exchanged their work

Even more surprising was that while feedback with a neighbor and switched roles from “au-

did increase achievement on average, in 50 of the thor” to “editor.” The editor’s task was to “mark

studies (i.e., 38%), feedback actually made per- up” the story by using four different colored pen-

formance worse! cils to indicate the beginning of each phase, with

They concluded that, from a scientific point a fifth color to underline the two examples of

of view, most of the studies that had been un- figurative language. With the editor’s approval,

dertaken were a waste of time because they com- a story could be submitted to the teacher (the

pletely failed to take into account the reactions “chief editor”). Because each editor was responsi-

of the recipient. The question “What kind of ble for ensuring that the required elements were

Voices from the Middle, Volume 21 Number 2, December 2013

Wiliam | Assessment: The Bridge between Teaching and Learning

page

present, students took the role very seriously (not practice (Ericsson, Charness, Feltovich, & Hoff- 19

least because they were accountable to the chief man, 2006).

editor!). When students come to believe that smart is

Of course, one could list many more exam- not something you are but something you get,

ples of this kind, but what teachers routinely re- they seek challenging work, and in the face of

port is that students tend to be much tougher on failure, they increase

one another than most teachers would dare to be. effort. Student athletes quote

This is important because it suggests that with get this. They know that

well-structured peer-assessment, one can achieve to improve, they must

better outcomes than would be possible with one practice things they

adult for every student. can’t yet do, rather than

just simply rehearse the

Students Owning Their Own Learning things they know how to

As Rick Stiggins (Stiggins, Arter, Chappuis, & do. We need to get stu-

Chappuis, 2004) reminds us, the most important dents to understand this

instructional decisions are not made by teach- in the English language

ers—they are made by students. When students arts classroom, too.

believe they cannot learn, when challenging tasks Ultimately, we would

are just one more opportunity to find out that want students to resent

you are not very smart, many students disengage. work that does not challenge them, because they

And this is perfectly understandable. What stu- would understand that easy work doesn’t help

dents are really doing when they disengage is de- them improve. In the best classrooms, students

nying the teacher the opportunity to make any would not mind making mistakes, because mis-

judgment about what the student can do—after takes are evidence that the work they are doing is

all, it is better to be thought lazy than dumb. This hard enough to make them smarter.

is why the most important word in any teacher’s

vocabulary is yet. When a student says, “I can’t do Conclusion

it,” the teacher responds with “yet.” This is more People often want to know “what works” in ed-

than just sound psychology. It is actually what ucation, but the simple truth is that everything

we are learning about the nature of expertise and works somewhere, and nothing works every-

where it comes from. where. That’s why research can never tell teach-

Of course individuals vary in their natural ers what to do—classrooms are far too complex

gifts, but these differences are very small to begin for any prescription to be possible, and varia-

with. What happens is the small initial advan- tions in context make what is an effective course

tages of some students quickly become magnified of action in one situation disastrous in another.

when the students with these small advantages Nevertheless, research can highlight for teachers

work hard, engage, and improve, while those who what kinds of avenues are worth exploring and

are slightly behind avoid challenge, and thus miss which are likely to be dead ends, and this is why

out on the chance to improve. As the title of a classroom formative assessment appears to be so

recent book by Geoff Colvin (2010) makes clear, promising. Across a range of contexts, attend-

“Talent is overrated.” It is practice that creates ing not to what the teacher is putting into the

expertise. Chess grandmasters don’t have higher instruction but to what the students are getting

IQs than average chess players—they just prac- out of it has increased both student engagement

tice more. Indeed, in almost all areas of human and achievement.

expertise, from violin playing to radiography, Different teachers will find different aspects

expertise is the result of ten years of deliberate of classroom formative assessment more effec-

Voices from the Middle, Volume 21 Number 2, December 2013

Wiliam | Assessment: The Bridge between Teaching and Learning

page

20 tive for their personal styles, their students, and Colvin, G. (2010). Talent is overrated: What really sepa-

the contexts in which they work—so each teach- rates world-class performers from everybody else. New

York, NY: Penguin.

er must decide how to adapt the ideas outlined

Claxton, G. L. (1995). What kind of learning does self-

above for use in their practice. Of course, as al-

assessment drive? Developing a “nose” for quality:

ways, “more research is needed,” but the breadth Comments on Klenowski. Assessment in Education:

of the available research suggests that if teachers Principles, Policy, and Practice, 2, 339–343.

develop their practice focused on the principles Ericsson, K. A., Charness, N., Feltovich, P. J., & Hoff-

outlined above, they are unlikely to fail because man, R. R. (2006). The Cambridge handbook of

of the neglect of subtle or delicate features. There expertise and expert performance. Cambridge, UK:

will never be an optimal model, but as long as Cambridge University Press.

teachers continue to investigate that extraordi- Kluger, A. N., & DeNisi, A. (1996). The effects of

feedback interventions on performance: A historical

narily complex relationship between “What did

review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback

I do as a teacher?” and “What did my students intervention theory. Psychological Bulletin, 119,

learn?” good things are likely to happen. 254–284.

Ryle, G. (1949). The concept of mind. London, UK:

Note Hutchinson.

1. The representation in Figure 1 was developed by Mar- Sadler, D. R. (1989). Formative assessment and the

nie Thompson and Dylan Wiliam, and was first pub- design of instructional systems. Instructional Sci-

lished as Leahy, S., Lyon, C., Thompson, M., & Wiliam, ence, 18, 119–144.

D. (2005). Classroom assessment: Minute-by-minute Slavin, R. E., Hurley, E. A., & Chamberlain, A. M.

and day-by-day. Educational Leadership, 63(3), 18–24. It is (2003). Cooperative learning and achievement. In

used here by permission of Educational Testing Service, W. M. Reynolds & G. J. Miller (Eds.), Handbook

Princeton, NJ. of psychology volume 7: Educational psychology

(pp. 177-198). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

References Stiggins, R. J., Arter, J. A., Chappuis, J., & Chappuis, S.

Brown, A. L., & Campione, J. C. (1995). Guided dis- (2004). Classroom assessment for student learning:

covery in a community of learners. In K. McGilly doing it right—using it well. Portland, OR: Assess-

(Ed.), Classroom lessons: Integrating cognitive ment Training Institute.

theory and classroom practice (pp. 229–270).

Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Dylan Wiliam works with schools, districts, and state and national governments all over the world

to improve education. He lives virtually at www.dylanwiliam.net and physically in New Jersey.

Voices from the Middle, Volume 21 Number 2, December 2013

You might also like

- KIndergarten Class Programs (Blocks of Time)Document2 pagesKIndergarten Class Programs (Blocks of Time)Paul JohnNo ratings yet

- Book Character Parade Mechanics 2Document1 pageBook Character Parade Mechanics 2Mary NicoleNo ratings yet

- Module 5: Purposes and Functions of Language Assessment & TestDocument15 pagesModule 5: Purposes and Functions of Language Assessment & TestChasalle Joie GD100% (1)

- DLP VerbDocument3 pagesDLP VerbAngela MacaraegNo ratings yet

- Grade 2 Reading-AccomplishmentDocument9 pagesGrade 2 Reading-AccomplishmentCelia Edillor SalubreNo ratings yet

- English 8 Lesson PlanDocument6 pagesEnglish 8 Lesson PlanANNABEL PALMARINNo ratings yet

- DLL W4 Q2 English 5Document5 pagesDLL W4 Q2 English 5Marvin Lapuz100% (1)

- Approaches To Language Testing ReflectionDocument3 pagesApproaches To Language Testing ReflectionFeby Lestari100% (1)

- GRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Log: JUNE 4-8, 2018 (WEEK 1)Document4 pagesGRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Log: JUNE 4-8, 2018 (WEEK 1)Aletheia Vivien Ablona0% (1)

- Demo Teaching 1Document6 pagesDemo Teaching 1Ernani Moveda FlorendoNo ratings yet

- Challenges in Teaching Listening Skills in Blended Learning ModalityDocument14 pagesChallenges in Teaching Listening Skills in Blended Learning ModalityLoraine Kate Salvador LlorenNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan ObservationDocument4 pagesLesson Plan ObservationCristina SarmientoNo ratings yet

- POST Reading StrategiesDocument8 pagesPOST Reading StrategiesMENDiolapNo ratings yet

- (793978731) English GR 8-TOS Reading, Writing, Speaking, Viewing & ListeningDocument4 pages(793978731) English GR 8-TOS Reading, Writing, Speaking, Viewing & ListeningMark Joseph DelimaNo ratings yet

- Marco Meduranda Natatanging Guro (Autosaved)Document23 pagesMarco Meduranda Natatanging Guro (Autosaved)marco24medurandaNo ratings yet

- Reading MatrixDocument7 pagesReading MatrixMacharisse Joanne Jumoc LabadanNo ratings yet

- IPPDDocument2 pagesIPPDJL Indiano100% (1)

- A Demonstration Lesson Plan in English 5Document7 pagesA Demonstration Lesson Plan in English 5Yhple DirectoNo ratings yet

- Why Do We AssessDocument25 pagesWhy Do We AssessAngeline MicuaNo ratings yet

- School Reading Remediation Program (SRRP) Monitoring Tool: Description As Stated Issues and Concerns Recommendation/sDocument10 pagesSchool Reading Remediation Program (SRRP) Monitoring Tool: Description As Stated Issues and Concerns Recommendation/sRhea M. VillartaNo ratings yet

- San Pedro Integrated School: EN7G-II-a-1Document6 pagesSan Pedro Integrated School: EN7G-II-a-1Eljean LaclacNo ratings yet

- Linguistic Functional Feature Analysis of English Legal MemorandumDocument7 pagesLinguistic Functional Feature Analysis of English Legal MemorandumErikaNo ratings yet

- Strategies in Teaching Reading Comprehension - PNUDocument45 pagesStrategies in Teaching Reading Comprehension - PNUAnthony MarkNo ratings yet

- DLL Verbal and Non Verbal CueDocument5 pagesDLL Verbal and Non Verbal CueSherry Love Boiser AlvaNo ratings yet

- Minh Observation Lesson Plan Grade 4 Context CluesDocument4 pagesMinh Observation Lesson Plan Grade 4 Context Cluesapi-352252623No ratings yet

- GRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Plan Aringin High School 9 Jennilyn A. Paloma English February 18, 2020 4 (Fourth) TuesdayDocument3 pagesGRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Plan Aringin High School 9 Jennilyn A. Paloma English February 18, 2020 4 (Fourth) TuesdayPalomaJudelNo ratings yet

- RemedialDocument5 pagesRemedialNikko Franco TemplonuevoNo ratings yet

- SAIS Accreditation Sample Interview QuestionsDocument2 pagesSAIS Accreditation Sample Interview QuestionsMc Lindssey PascualNo ratings yet

- Final Demonstration Lesson Plan in English 8Document4 pagesFinal Demonstration Lesson Plan in English 8Nicole Mae GarciaNo ratings yet

- Activties For English Month Celebration2Document6 pagesActivties For English Month Celebration2Anna ANo ratings yet

- English AccomplishmentDocument4 pagesEnglish AccomplishmentjessNo ratings yet

- Active and Passive Voice Mimi-1Document3 pagesActive and Passive Voice Mimi-1MimiNo ratings yet

- Declamation Competition - MechanicsDocument2 pagesDeclamation Competition - MechanicsGene Justene Pampolina BarunoNo ratings yet

- Editable Mid Year Review Portfolio 1 Cover Page 2Document9 pagesEditable Mid Year Review Portfolio 1 Cover Page 2May Ann C. PayotNo ratings yet

- Award Certificates Templates by Sir Tristan AsisiDocument6 pagesAward Certificates Templates by Sir Tristan AsisiJokaymick LacnoNo ratings yet

- 3rd Chat Session AnswersDocument4 pages3rd Chat Session AnswersKen SisonNo ratings yet

- The Three Wishes: 2 Assessment Grade IIDocument4 pagesThe Three Wishes: 2 Assessment Grade IIAttaNo ratings yet

- English Topics RBEC & K-12Document23 pagesEnglish Topics RBEC & K-12Zee Na0% (1)

- Using Modals Lesson Plan With Worksheets and BINGO CardDocument9 pagesUsing Modals Lesson Plan With Worksheets and BINGO CardSITTI MONA MAGTACPAO0% (1)

- Grammar and Punctuation - Subject-Verb AgreementDocument3 pagesGrammar and Punctuation - Subject-Verb AgreementAlex MarinNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan RemedialDocument7 pagesLesson Plan RemedialNur AskinahNo ratings yet

- Gradual Psychological Unfolding On SupervisionDocument1 pageGradual Psychological Unfolding On SupervisionLeodigaria ReynoNo ratings yet

- Designing Contextualized Learning Activity SheetsDocument39 pagesDesigning Contextualized Learning Activity SheetsMaribeth EspaderaNo ratings yet

- Module 5 - Development of Classroom Assessment ToolsDocument10 pagesModule 5 - Development of Classroom Assessment ToolsJoemar BaquiranNo ratings yet

- Reflection PNUDocument2 pagesReflection PNUJohn Carlo DomantayNo ratings yet

- Action Plan in EnglishDocument2 pagesAction Plan in EnglishEUDELYN ENCARGUEZNo ratings yet

- 4th Day Narrative Report VINSET Accomplishment ReportDocument2 pages4th Day Narrative Report VINSET Accomplishment ReportNerissa Pulido GarciaNo ratings yet

- Grade 6 DLL ENGLISH 6 Q1 Week 3Document10 pagesGrade 6 DLL ENGLISH 6 Q1 Week 3Jess Ica D-BalcitaNo ratings yet

- Unit Standard and Competencies Diagram English 7 2qDocument1 pageUnit Standard and Competencies Diagram English 7 2qAbigail Dizon100% (1)

- Context Clues Lesson Plan 8Document2 pagesContext Clues Lesson Plan 8api-302299721No ratings yet

- Reflection - Punctuation For BlogDocument3 pagesReflection - Punctuation For Blogapi-346410491No ratings yet

- Star ObservationDocument15 pagesStar ObservationRubz Oliveros ArnedoNo ratings yet

- Deped - Division 1 Sta. Barbara 1Document10 pagesDeped - Division 1 Sta. Barbara 1Carl VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesDetailed Lesson PlanSherylNo ratings yet

- Lesson Exemplar Blank TemplateDocument2 pagesLesson Exemplar Blank TemplateR TECHNo ratings yet

- Guidelines in ADM Content Evaluation RegionDocument7 pagesGuidelines in ADM Content Evaluation RegionCARMEL GRACE SIMAFRANCA100% (2)

- English LESSON PLANDocument3 pagesEnglish LESSON PLANJulie Ann R. BangloyNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Guide in English 8Document19 pagesCurriculum Guide in English 8Rosie Siglon GallardoNo ratings yet

- 10 Lesson 2 Curriculum Evaluation Through Learning AssessmentDocument13 pages10 Lesson 2 Curriculum Evaluation Through Learning AssessmentMarjene Dichoso100% (1)

- PDPDocument7 pagesPDPapi-302003110No ratings yet

- DLL - English 2 - Q1 - W2Document3 pagesDLL - English 2 - Q1 - W2Glene M CarbonelNo ratings yet

- Report To The Community - KentDocument2 pagesReport To The Community - KentCFBISDNo ratings yet

- P4C Seminar-495syllabusDocument3 pagesP4C Seminar-495syllabusVũ Ánh Tuyết Trường THPT ChuyênNo ratings yet

- Wisc IiiDocument52 pagesWisc IiiAnaaaerobiosNo ratings yet

- Action Plan in Mathematics: Buyo Elementary SchoolDocument2 pagesAction Plan in Mathematics: Buyo Elementary SchoolEdz Nacion100% (1)

- AppraisalDocument3 pagesAppraisalapi-338691357No ratings yet

- GHL5006 BO WRIT2 L5B2 V1 August 2020 - Business ObligationsDocument11 pagesGHL5006 BO WRIT2 L5B2 V1 August 2020 - Business ObligationsBuy SellNo ratings yet

- Activity 2 in EPPDocument2 pagesActivity 2 in EPPJustine Jerk Badana100% (2)

- The Lighthouse Science Project: A Performance Task For 4 Grade StudentsDocument17 pagesThe Lighthouse Science Project: A Performance Task For 4 Grade Studentsapi-302628627No ratings yet

- School Culture and Its Relationship With Teacher LeadershipDocument15 pagesSchool Culture and Its Relationship With Teacher LeadershipCarmela BorjayNo ratings yet

- Meningkatkan Konsentrasi Belajar Peserta Didik Dengan Bimbingan Klasikal Metode Cooperative Learning Tipe JigsawDocument10 pagesMeningkatkan Konsentrasi Belajar Peserta Didik Dengan Bimbingan Klasikal Metode Cooperative Learning Tipe Jigsawkuzuha yuzurihaNo ratings yet

- Assignment - HPGD1103 - Curriculum DevelopmentDocument28 pagesAssignment - HPGD1103 - Curriculum DevelopmentHanani Izzati100% (1)

- PATH-Fit 3 Outdoor and Adventure Activities (Laro NG Lahi) Syllabus 2020-2021Document8 pagesPATH-Fit 3 Outdoor and Adventure Activities (Laro NG Lahi) Syllabus 2020-2021Klint Tomena100% (2)

- Improve Students Listening Comprehension Achievement by Using Video MediaDocument2 pagesImprove Students Listening Comprehension Achievement by Using Video MediaoctavianaNo ratings yet

- Management Science NotesDocument20 pagesManagement Science NotesKaruNo ratings yet

- 4113 Final Webquest Colonial America Lesson PlansDocument8 pages4113 Final Webquest Colonial America Lesson PlansMarkJLanzaNo ratings yet

- DLP En8 q2 Grammatical SignalsDocument6 pagesDLP En8 q2 Grammatical Signalsmavlazaro.1995No ratings yet

- Compare and Contrast Wampanoag and Pilgrim Kids Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesCompare and Contrast Wampanoag and Pilgrim Kids Lesson Planapi-563439476No ratings yet

- Ar - RRLDocument16 pagesAr - RRLMangulabnan, Jamie B.No ratings yet

- CSTP 6 Ulibarri 11Document9 pagesCSTP 6 Ulibarri 11api-678352135No ratings yet

- Test Bank For Essentials of Human Development A Life Span View 2nd Edition by KailDocument24 pagesTest Bank For Essentials of Human Development A Life Span View 2nd Edition by Kailmichaelwatson05082003xns100% (47)

- MST/MCT Holistic Grade C+Document14 pagesMST/MCT Holistic Grade C+Maitha ANo ratings yet

- L and T Resources List MathDocument10 pagesL and T Resources List MathStevieNgNo ratings yet

- Accounting Graduate Employers' Expectations and The Accounting Curriculum PDFDocument10 pagesAccounting Graduate Employers' Expectations and The Accounting Curriculum PDFFauzan AdhimNo ratings yet

- Appendix A: Sample Letters For ParentsDocument30 pagesAppendix A: Sample Letters For Parentsshiela manalaysayNo ratings yet

- Assorted Test 1 I. Listening (50 Points)Document9 pagesAssorted Test 1 I. Listening (50 Points)Trương Ngọc Lê Huyền33% (6)

- How Successful Teachers Create A Nurturing Classroom CultureDocument2 pagesHow Successful Teachers Create A Nurturing Classroom CultureJoana HarvelleNo ratings yet

- EHR-05-Labour Law and Industrial Relations-EPGPDocument7 pagesEHR-05-Labour Law and Industrial Relations-EPGPAbirami NarayananNo ratings yet

- ENGDocument2 pagesENGShahil Alam100% (1)

- World Geography Puzzles: Countries of the World, Grades 5 - 12From EverandWorld Geography Puzzles: Countries of the World, Grades 5 - 12No ratings yet

- World Geography - Time & Climate Zones - Latitude, Longitude, Tropics, Meridian and More | Geography for Kids | 5th Grade Social StudiesFrom EverandWorld Geography - Time & Climate Zones - Latitude, Longitude, Tropics, Meridian and More | Geography for Kids | 5th Grade Social StudiesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Archaeology for Kids - Australia - Top Archaeological Dig Sites and Discoveries | Guide on Archaeological Artifacts | 5th Grade Social StudiesFrom EverandArchaeology for Kids - Australia - Top Archaeological Dig Sites and Discoveries | Guide on Archaeological Artifacts | 5th Grade Social StudiesNo ratings yet

- Successful Strategies for Teaching World GeographyFrom EverandSuccessful Strategies for Teaching World GeographyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Power of Our Supreme Court: How Supreme Court Cases Shape DemocracyFrom EverandThe Power of Our Supreme Court: How Supreme Court Cases Shape DemocracyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Economics for Kids - Understanding the Basics of An Economy | Economics 101 for Children | 3rd Grade Social StudiesFrom EverandEconomics for Kids - Understanding the Basics of An Economy | Economics 101 for Children | 3rd Grade Social StudiesNo ratings yet

- Indigenous Storywork: Educating the Heart, Mind, Body, and SpiritFrom EverandIndigenous Storywork: Educating the Heart, Mind, Body, and SpiritNo ratings yet