Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Trachoma

Uploaded by

nurlailaela23Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Trachoma

Uploaded by

nurlailaela23Copyright:

Available Formats

Seminar

Trachoma

Hugh R Taylor, Matthew J Burton, Danny Haddad, Sheila West, Heathcote Wright

Lancet 2014; 384: 2142–52 Trachoma is the most common infectious cause of blindness. Repeated episodes of infection with Chlamydia trachomatis

Published Online in childhood lead to severe conjunctival inflammation, scarring, and potentially blinding inturned eyelashes (trichiasis

July 17, 2014 or entropion) in later life. Trachoma occurs in resource-poor areas with inadequate hygiene, where children with

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

unclean faces share infected ocular secretions. Much has been learnt about the epidemiology and pathophysiology of

S0140-6736(13)62182-0

trachoma. Integrated control programmes are implementing the SAFE Strategy: surgery for trichiasis, mass

Melbourne School of

Population and Global Health,

distribution of antibiotics, promotion of facial cleanliness, and environmental improvement. This strategy has

University of Melbourne, successfully eliminated trachoma in several countries and global efforts are underway to eliminate blinding trachoma

Carlton, VIC, Australia worldwide by 2020.

(Prof H R Taylor AC);

International Centre for

Eye Health, Department of

Introduction Epidemiology

Clinical Research, London Trachoma is a blinding infection caused by an ancient Trachoma is still endemic in many of the poorest and more

School of Hygiene & Tropical organism. Chlamydia trachomatis evolved with the remote areas of Africa, Asia, Australia, and the Middle East

Medicine, London, UK

dinosaurs, and all vertebrates have evolved with their (figure 2). Active trachoma affects an estimated 21 million

(M J Burton FRCOphth);

Global Vision Initiative, own chlamydial strains.1,2 Trachoma remains the most people with about 2·2 million blind or severely visually

Emory Eye Center, Emory common infectious cause of blindness.3 The intense impaired. A further 7·3 million have trichiasis3 (table 1).

University School of Medicine, conjunctival inflammation with follicles recognised as An intensive global trachoma mapping effort is underway

Atlanta, GA, USA

active trachoma (TF) is sustained by repeated episodes at present. WHO classes 53 countries as endemic for

(D Haddad MD); Wilmer Eye

Institute, Johns Hopkins of reinfection and reflects a sustained immune- trachoma10,11 and estimates that 229 million people live in

Hospital, Baltimore, MD, USA mediated response to chlamydial antigens.4 This endemic areas, with most blinding trachoma in Africa.12,13

(Prof S West PhD); and Centre inflammation causes scarring, distortion of the lid, and Although few up to date prevalence data are available from

for Eye Research Australia,

inturning of the lid (entropion), with the eyelashes China and India, with their large populations even a low

University of Melbourne, East

Melbourne, VIC, Australia touching the cornea (trichiasis) that leads to blindness prevalence could substantially alter global estimates.

(H Wright FRANZCO) (figure 1). The key to trachoma is that repeated episodes Active trachoma (follicular or severe inflammatory

Correspondence to: of reinfection and inflammation lead to the blinding trachoma) is most common in children younger than

Prof Hugh R Taylor, complications.4 5 years and the prevalence can reach 60% or more.14–16

Harold Mitchell Chair of

As human beings evolved, occasional chlamydial The greatest load of infection is also in young children.17

Indigenous Eye Health,

Melbourne School of Population conjunctivitis did not apparently lead to blindness. The prevalence of active trachoma decreases with age,

and Global Health, University of However, after the last Ice Age (about 8000 years BCE), few adults have signs of active trachoma, and even fewer

Melbourne, Carlton, VIC 3053, when people were crowded in growing communities have evidence of infection.14,17–19 As active inflammation

Australia

and hygiene was poor, the frequency of reinfection wanes, conjunctival scarring becomes more apparent;

h.taylor@unimelb.edu.au

increased and blinding trachoma resulted.6 Crowding rates increase with age so that at over 25 years, up to 90%

and poor hygiene lead to outbreaks of chlamydial of people could have scarring.20 Rates of active trachoma

infections in a range of birds, mammals, and are generally similar by sex at young ages, but scarring

marsupials.7 Trachoma rates increased greatly as trichiasis and loss of vision are generally more common

crowding and poor living standards increased at the end in women than in men.14,20 This difference is attributed to

of the Agricultural Revolution and the start of the longer exposure of women to infection because they are

Industrial Revolution, but waned in the 20th century as more likely than men are to care for young children.

living standards improved.6 The disappearance of The prevalence of scarring, trichiasis, and corneal

trachoma from more developed countries was hastened opacities in older people relates to their exposure to

with the introduction of sulpha drugs in the 1930s and trachoma when they were young. This concept is important

antibiotics in the 1940s. because even when active trachoma has disappeared, the

However, trachoma still affects millions of people late sequelae, including trichiasis, can still occur for

in the least developed countries. In recognition of the decades.21,22 Persisting episodes of infection with

likelihood that spontaneous improvement in living C trachomatis or other ocular infections can contribute to

conditions and disappearance of trachoma could take progressive scarring, so reduction of these exposures

many decades, a specific global commitment has benefit adults.

been made to eliminate trachoma. A resolution of the Many cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have

World Health Assembly in 1997 established the linked clean faces to lower risk of trachoma.6,23

Global Alliance for the Elimination of Blinding Improvement in facial cleanliness also decreases the

Trachoma by the year 2020 (GET 2020) and much severity of active disease, probably by lowering the

progress is being made to eliminate the disease. likelihood of transmission.24

Some successes have led to increased resources and Water is necessary for face washing, and trachoma often

effort as set out here. occurs in communities or households without an adequate

2142 www.thelancet.com Vol 384 December 13, 2014

Seminar

water supply. Several studies have identified a positive

A B

association between the distance to the water source and

the prevalence of active trachoma.23 However, the provision

of water to communities does not necessarily ensure that

infection or active trachoma rates will decline.25 The

decision to use water for hygiene is complex and is a very

important factor.26

Within communities, trachoma clusters both by

neighbourhood and by household.14,27,28 Studies of the re-

emergence of infection after mass azithromycin

treatment show that it reappears in households within C D

6 months, but takes up to a year to be evident in

neighbouring households.29

Overcrowding is a risk factor for trachoma; the risk of

children having active disease increases with the number

of people per sleeping room.28 Crowded conditions and

close contact enable exchange of infected secretions

among children especially if they have unclean faces and

share a bed. Although a large family in itself is not a risk

factor, the increased risk of contact with potentially

infected children is. In Nathan Congdon and colleagues’ E

study,30 mothers of children with trachoma were more

likely to have active disease than women who did not take

care of children or whose children did not have trachoma.

Eye-seeking flies have been presumed to be physical

vectors for C trachomatis. Although C trachomatis has

been identified in trapped flies,31,32 whether they can

transmit infection is not known. The presence of a

functional latrine near the house has been associated

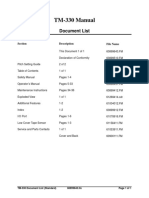

with lower trachoma prevalence.14 How the presence of a Figure 1: Clinical features of trachoma and the WHO simplified grading5

(A) Trachomatous inflammation–follicular (TF); the presence of five or more follicles in the upper tarsal conjunctiva. (B)

latrine would decrease trachoma is not clear, although Trachomatous inflammation–intense (TI); pronounced inflammatory thickening of the tarsal conjunctiva that obscures

latrines might reduce breeding sites for the eye-seeking more than half of the normal deep tarsal vessels. (C) Trachomatous scarring (TS); scars are easily visible as white lines,

fly Musca sorbens,33 or could be simply a marker for bands, or sheets in the tarsal conjunctiva. (D) Trachomatous trichiasis (TT); at least one eyelash rubs on the eyeball;

families with better overall hygiene.34 evidence of recent removal of inturned eyelashes should also be graded as trichiasis. (E) Corneal opacity (CO); easily

visible corneal opacity over the pupil.

Pathogenesis

The causative organism Active trachoma Blindness Trichiasis

Trachoma is caused by the obligate intracellular Gram- 1956 400 NA NA

negative bacterium C trachomatis, which has a single 1971 400–500 1–2 NA

chromosome of about 1 Mbp and a multicopy plasmid 1981 500 6–7 NA

that functions as a virulence factor.2 This unusual

1985 360 6–9 NA

organism has a biphasic developmental cycle. Initially the

1994 146 5·9 NA

small, hardy, metabolically inactive elementary bodies

1996 NA NA 10·6

attach to and enter epithelial cells. Once inside, elementary

2003 84·0 1·6 7·6

bodies transform into the larger, metabolically active

2007 40·6 NA 8·2

reticulate bodies within an intracytoplasmic vacuole, the

2011 21·4 2·2 7·3

inclusion body, and replicate by binary fission. The

reticulate bodies transform into elementary bodies before Data are millions of individuals. NA=not available.

host-cell lysis and their release—the elementary body is

Table 1: WHO estimates of the global burden of trachoma, by year3,6,9

the transmissible form. No non-human reservoir for the

human strains of chlamydia is known.

Endemic trachoma is caused by C trachomatis serotypes However, the ocular serotypes have lost the capacity to

A, B, Ba, and C. C trachomatis infection of the genital tract synthesise tryptophan; and there is polymorphism in the

is generally caused by serotypes D to K, which can also tarp and pmp genes.35 Whole-genome analysis of

infect the eye, causing ophthalmia neonatorium in infants C trachomatis suggests that extensive recombination

or inclusion conjunctivitis in adults. The basis for the tissue between different strains is possible and that typing based

tropism of the serotypes has not been fully elucidated. on ompA might not be as reliable as previously thought.36

www.thelancet.com Vol 384 December 13, 2014 2143

Seminar

infection could contribute to continued development of

Algeria

Nauru scarring.44,45 The risk of scarring has also been associated

Mauritania with the presence of other ocular pathogens, which

Kiribati suggests a role for chronic non-chlamydial conjunctivitis.46

The Gambia

Australia

However, not every person within an endemic community

Burma develops scarring, and 39% of the variability is attributable

Benin to human genetic factors.47 Moreover, scarring and trichiasis

Botswana

can continue to develop in people living in regions that are

Central African Republic

Vanuatu no longer endemic,48 which suggests that tissue damaged

Solomon Islands by previous chlamydial infection can undergo progressive

Afghanistan cicatrisation, or that after damage other drivers, such as

Fiji

Burundi

other bacterial pathogens, can contribute.46

Cambodia Conjunctival scarring precedes the development of

Mali trichiasis. The 7-year incidence of trichiasis in Tanzanian

Eritrea

women was 9·2% in those with tarsal scarring, and only

Guinea-Bissau

Malawi 0·6%, in those without scarring.49 Incident trichiasis was

Guinea also associated with the presence of active trachoma at

Cameroon baseline. The presence of infection at follow-up increased

Chad

Kenya

the risk of trichiasis by two and a half times, which

South Sudan suggests that persistent episodes of infection play a part.

Zambia In The Gambia, where trachoma rates are substantially

Burkina Faso

lower than in Tanzania, the 12-year progression from

Yemen

Nepal scarring to trichiasis in a cohort of 326 people, including

Niger men, was 6·4%—about half that of Tanzania.50

Tanzania

Senegal

Uganda

Histopathology

Sudan Active follicular trachoma is characterised by a diffuse

Mozambique inflammatory-cell infiltrate of the conjunctiva

Egypt

(lymphocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, and plasma

Pakistan

Nigeria cells) punctuated by lymphoid follicles (B cells

Ethiopia surrounded by a T-cell mantle).51 Trachomatous

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 conjunctival scarring shows disruption of loose, regular

Number of people at risk (millions) type 1 stromal collagen and dense sheets and bundles of

Figure 2: Estimates of the population of at risk trachoma by countries compact type V collagen.52 The epithelial cells are thinned

Brazil (1·3 million), China (455 million), and India (425 million) have been excluded from the figure.8 and goblet cells reduced. In-vivo confocal microscopy

shows changes in apparently unscarred eyelids, which

Pathophysiology suggests a continuum from subclinical to clinically

Blinding trachoma is the result of a complex interaction apparent scarring.53 Conjunctival scarring is commonly

between chlamydial infection and the immune response associated with clinical inflammation and inflammatory-

occurring over many years.37 Scarring develops more cell infiltrates.53,54

commonly and at a younger age in populations with higher

burdens of active trachoma and chlamydial infection, Immune response

suggesting that chlamydial infection has a central role in The mucosal response to C trachomatis infection involves

the disease process.38 Longitudinal studies link scarring to several components of the immune system, although the

chronic conjunctival inflammation, which can persist long features of protective and pathological responses are still

after infection has resolved.37 unclear.37

Most children with active trachoma do not develop The infection triggers an innate immune response,

trichiasis and blindness. In hyperendemic areas, a possibly driven from the epithelium through pattern-

subgroup of children, about 8–10%, seem to have constant recognition receptors. Infection of human epithelial cells

infection39,40 and persistent severe inflammation.41 The in vitro provokes a pronounced proinflammatory response,

incidence of scarring is almost five-times higher in these with the production of chemokines and cytokines.55

children than in children with active trachoma but without Conjunctival transcriptome studies in children with active

severe inflammation.42 Variation in the response to trachoma show prominent innate responses, with

chlamydial infection might explain this difference, as could increased proinflammatory mediators and recruitment

frequency of exposure and reinfection. Infection without and activation of natural killer cells and neutrophils.56,57

an obvious inflammatory response can occur in adults, Immunohistochemistry shows that some of these factors

with scarring in hyperendemic communities.23,43 This arise from epithelial cells.58

2144 www.thelancet.com Vol 384 December 13, 2014

Seminar

The resolution of chlamydial infection is thought to be active and scarring trachoma show increased amounts of

dependent on interferon γ, mediated through nitric oxide matrix metalloproteinases 7, 9, and 12,56,64,65 and a single

free radicals and the depletion of intracellular tryptophan nucleotide polymorphism of the catalytic region of matrix

and iron. Infected children have increased expression of metalloproteinase 9 affects the risk of scarring.68 These

the genes IFNγ and IL12p40, which suggests a type-1 findings suggest a role for matrix metalloproteinases in

CD4-expressing T-helper lymphocyte (Th1) cell-mediated scar formation.

immune response.56 Other sources of interferon γ could Corneal opacity and loss of vision can occur within a

include natural killer cells and CD8-expressing T cells.56,59 year in up to a third of individuals with untreated

Human challenge experiments and trachoma vaccine trichiasis.69 Even without vision loss trichiasis leads to

trials in the 1960s suggested that acquired immunity to substantial disability and reduced quality of life.70,71

reinfection is serovar specific, weak, and short-lived.37 A

longitudinal population-based study identified shorter Assessment of burden of disease

infection episodes with increasing age, again suggestive Overview

of limited acquired immunity,18 although another possible Trachoma interventions are planned at the district level,

explanation is less frequent episodes of reinfection. The though implemented at the community or household

contribution of humoral immunity to infection remains level. They aim to eliminate blinding trachoma, partly by

unclear, but it is probably limited.37 The degree of disrupting transmission of infection, and are implemented

protection identified in non-human primate vaccine at the district level to minimise the reintroduction of

studies was only partial and serovar specific, although infection into treated communities. Therefore, the district-

this protection was no more than that conferred by level trachoma prevalence is used to identify where

recovery from a primary ocular infection.60 programmes are needed (appendix).11 See Online for appendix

At the start of 2012, trachoma control activities covered

Scarring about half of the areas deemed to be at risk of trachoma.

Trachomatous scarring can result from a T-cell-mediated In June, 2012, the UK Department for International

immune response to repeated chlamydial antigen Development gave £10 million for a Global Trachoma

exposure54 or an innate proinflammatory response Mapping Programme.8 This project aims to complete the

arising from the infected epithelium. 61 mapping of trachoma in unmapped districts by March,

Evidence for specific T-cell responses is limited.37 2015. Through this consortium new methods, training

Findings of studies in non-human primates suggested materials, and data management systems have been

that the inflammatory disease resulted from a specific cell- developed to save time and ensure harmonisation.

mediated response to a chlamydial heat shock protein,

cHsp60.4 Results from human studies are more mixed: Clinical grading

antibodies to cHsp60 are more common (possibly related The WHO simplified grading system was designed for

to increased exposure), and responses of peripheral-blood non-specialists (eg, eye nurses) to rapidly assess the

mononuclear cells to cHsp60 are weaker in people with prevalence and severity of disease within a population.5

conjunctival scarring than in those without scarring.62,63 By contrast, the earlier, more detailed systems for grading

However, there is little evidence from human beings to trachoma were used by experienced eye specialists. The

suggest that the conjunctival scarring results from a Th2 simplified grading focuses on the presence or absence of

cell-mediated immune response, by contrast with five key clinical signs of the disease. Each of the signs

schistosomiasis, which has been associated with a Th2 should be scored independently.

response.56,64,65 Population-based assessment of the prevalence of the

Evidence suggesting that an innate proinflammatory clinical signs of trachoma is the starting point for a

epithelial response contributes to tissue damage includes trachoma control programme. Active trachoma is most

a murine TLR2 (an innate system of pattern-recognition prevalent in young children, so screening for active

receptors) knockout model for genital chlamydial trachoma (TF and TI) is mostly restricted to children

infection; affected animals had lower production of aged 1–9 years. Adults (older than 15 years) are generally

inflammatory cytokines, fewer inflammatory cells, and screened for trachomatous trichiasis (TT).

less scarring than normal mice.66 The conjunctival

transcriptome analyses of both children with active Laboratory diagnosis

inflammatory disease and adults with scarring show Trachoma is a clinical diagnosis. The laboratory detection

enrichment of innate pathways.56,65 Trachoma scarring has of C trachomatis is not used for programmatic purposes

been associated with polymorphisms of the interleukin 8 or to diagnose individual cases, but it is often used in

and colony-stimulating factor 2 (CSF2) loci.67 research. Laboratory tests developed for urogenital

The matrix metalloproteinases are integral to tissue infection are often used for ocular infection. Although

homoeostasis and are also involved in tissue destruction laboratory diagnosis of ocular C trachomatis has

and fibrosis. These proteolytic enzymes are produced by improved, there is still no single accepted gold standard.

inflammatory cells, fibroblasts, and epithelium. Both C trachomatis has been cultured since 1957, but culture is

www.thelancet.com Vol 384 December 13, 2014 2145

Seminar

expensive and time-consuming; although very specific, be used as basis for the survey as well, to reduce costs.11

it is not very sensitive. The Global Mapping for Trachoma Program uses

Nucleic acid amplification techniques are highly population-based surveys.80

sensitive and specific.72,73 C trachomatis DNA or RNA is Other methods have been developed. Trachoma rapid

selectively amplified and detected in ocular swabs or assessment81 has convenience sampling that is biased to

nasal secretions. Although the price per test is high find trachoma; because it targets the worst areas it can

(US$10–40 per test), these techniques can be cost effective help prioritise areas and show whether a district is free of

for programme assessment and decision making, trachoma, but it does not provide prevalence information.

especially on whether to stop antibiotic treatment Acceptance sampling trachoma rapid assessment82 is

implementation.74,75 A better understanding of the risk of based on lot quality assurance sampling but has been

re-emergence of infection or emergence where infection little used.

was previously absent is needed before criteria based on

testing for infection can be used.76 For programme Management and prevention: the SAFE strategy

purposes, the whole population does not need to be Overview

tested. Selective testing of a representative sample of The GET2020 campaign uses the SAFE strategy, a four-

people, shared use of laboratory capacity established for pronged approach to stop the cycle of reinfection within

HIV and tuberculosis programmes, and pooled testing of the community and to correct trichiasis.11 WHO and

samples can reduce costs, although careful understanding partners aim to scale up SAFE strategy programmes in

of the limitation of pooling is needed. affected countries in a timely and cost-effective way to

eliminate trachoma by 2020.

Relation between clinical disease and C trachomatis

infection Surgery

Clinical disease commonly occurs in the absence of Individuals with trachomatous trichiasis and entropion

demonstrable infection (table 2). At any given time, only are at risk of corneal opacification and vision loss. To

18–40% of individuals with less severe active disease (TF) prevent these features developing, the abrasive action of

will be PCR positive; 50–70% of those with severe lashes on the cornea must be stopped by surgical

inflammation (TI) will be PCR positive.43 Clinical signs of correction of the eyelid margin, with epilation perhaps as

active trachoma can persist long after infection has been an acceptable short-term option.83 Both bilamellar tarsal

cleared and DNA is undetectable.77 The poor association rotation and posterior lamellar tarsal rotation (or Trabut)

between clinical disease and infection, and the existence procedures are recommended by WHO.83–85

of clinical disease without detectable infection has led Trichiasis surgery programmes are cost effective at

some to question whether clinical signs should be the 13–78 international dollars per DALY.86 They have been

only means to determine when to stop treatment.78 widely implemented; an estimated 160 000 individuals

received surgical procedures in 2012.8 Trichiasis surgery

Survey methods improves vision slightly, reduces pain, and in some

The gold standard is a full-scale population-based cases reduces the severity of corneal opacity.85,87–89 The

prevalence survey with a cluster-randomised sampling success of many surgical programmes is undermined by

technique at the district level. Several sampling techniques recurrence rates that can be as high as 60% at 3 years.87,90–95

have been developed.79 If trachoma is expected to be highly However, in many cases the recurrent trichiasis is less

endemic and widespread, a larger geographical area could severe.85,87–89,96 Major risk factors for recurrence include

the preoperative severity of trichiasis, variability among

surgeons, and surgical technique.87,89,90 Other risk factors

Total Number

PCR-positive (%) include conjunctival inflammation95,97 and concurrent

chlamydial infection.98 The use of azithromycin after

Whole population 1282 46 (4%)

surgery with the aim of reducing recurrence has been

WHO simplified grading

assessed in three randomised controlled studies.87,90,99

TF absent 1174 27 (2%)

Two showed little effect but might have been

TF present 108 19 (18%)

underpowered; the largest study suggested a benefit.

Fine grading of follicles

Uptake of surgery is low in some areas, varying

Normal 793 6 (1%)

between 10% and 60%.100,101 Higher uptake was achieved

Some follicles, but less than TF 383 21 (5%)

with local village-based surgery.102 Barriers to surgery

TF WHO grade 98 16 (16%)

include lack of awareness,103 fear,98,104,105 the perceived

Follicles far exceeds TF 10 3 (30%) costs, transport difficulties,91,92,94,98,104,105 other responsi-

Modified from reference 43. TF=active trachoma. bilities,83 and lack of an escort.83 Surgical services can be

delivered in health centres or through outreach

Table 2: An example of the relation between active trachoma and

campaigns.83 Each has advantages, although most

presence of infection detected by PCR in endemic communities

surgery is delivered by outreach. Local resources and

2146 www.thelancet.com Vol 384 December 13, 2014

Seminar

preferences should be taken into account. Appropriately District survey

trained nurses can produce surgical outcomes equal to

those of ophthalmologists,106 but efficient, high-volume,

high-quality meticulous surgery with regular audit is TF is >10%: TF is <10%:

needed if the backlog of 7·3 million cases of trachoma- MDA, facial cleanliness, subdistrict level

tous trichiasis is to be cleared. and environmental surveys

improvements for

Epilation is an age-old treatment for trichiasis and is a at least 3 years

possible alternative if surgery is delayed, refused, or not

available. Several cross-sectional studies have found that TF is >10%: TF is >9–5%: TF is <5%:

in people who have not had surgery the risk of corneal MDA, facial cleanliness, facial cleanliness facial cleanliness,

opacification is lower in those who have epilation than in and environmental and environmental and environmental

improvements for improvements, and improvements,

those who do not.107,108 A controlled comparison of at least 3 years MDA can be targeted* but no further MDA†

repeated epilation with immediate surgery for minor

trachomatous trichiasis (fewer than six lashes touching Figure 3: WHO recommended interventions according to prevalence of TF11

TF=active trachoma. MDA=mass distribution of antibiotics. *Targeted means

the eye) found no difference in corneal opacity or visual

that no further survey is needed, but by use of the best available information,

acuity; however, significantly more lashes touched the villages, or aggregates of villages, are treated where trachoma rates are

eye in the epilation group.109 suspected to be high. †Precision for <5% is 4±2%.

Antibiotic treatment third round of treatment; however, the third round could

Antibiotics, oral azithromycin or topical tetracycline, are not be stopped in any of the communities.120 Reports of

used to lower C trachomatis numbers within endemic elimination after a single round of distribution might be

communities and thus disrupt the transmission of unrepresentative, because the coverage rate was

infection. Azithromycin (20 mg/kg up to 1 g) is the exceptionally high and affected individuals were given

preferred treatment where available. It is given as a topical tetracycline at follow-up visits.119,121 Other studies

single oral dose and is well tolerated. Topical tetracycline report a striking initial drop in the prevalence of

must be given for 6 weeks. infection after mass distribution followed up at

Four randomised controlled trials have assessed mass 6 months.117,122 For starting prevalences above 30%, WHO

distribution of azithromycin compared with no now advises that reassessment can be delayed for

treatment.110–114 In all four, the rate of C trachomatis 5 years,11 although some high prevalence (>50%)

infection was lowered by the intervention but only one communities might need 7 or more years of treatment.123

trial showed a clear reduction in clinical signs of active Mass distribution of antibiotics should continue until

disease at 12 months.114 A three-country randomised the prevalence of TF in children falls below 5% in

controlled trial showed oral azithromycin to be non- subdistricts or community clusters (appendix).11

superior to topical tetracycline; infection and clinical Debate about the duration of treatment for a community

disease declined significantly after treatment in both has centred on the mismatch between clinical signs and

trials.115 Furthermore, a randomised controlled trial in infection. Clinical signs can persist long after infection

Ethiopia of mass distribution of azithromycin once or has been cleared;77 this persistence could lead to

twice a year showed a decline of infection from a baseline unnecessary treatment of communities with low rates of

mean of 41·9% to 1·9% at 42 months with yearly and infection and more than 5% with clinical signs. Detection

from 38·3% to 3·2% with twice-yearly distribution.116 of infection is not practicable without a cheap point-of-

Despite the limited evidence from randomised controlled care assay and, even if a cost-effective one became

trials, the overwhelming evidence from cohort studies is available, the level of infection that would warrant

that the rate of clinical disease and the rate of infection treatment is not clear. WHO recommendations remain

both drop after mass distribution of antibiotics with high the best guide for the continuation of mass distribution of

coverage.112,115,117–119 District-wide mass distribution is antibiotics.

indicated when the proportion of children aged 1–9 years Mathematical modelling suggests that twice-yearly

with trachomatous inflammation, follicular (TF) is treatment is more effective than annual treatment in high-

greater than 10%.11 For starting prevalence rates of 5–9%, prevalence communities,124 although a 2009 randomised

targeted treatment is recommended (figure 3).11 controlled trial did not confirm this finding.125

WHO recommends that for a starting prevalence of In 2011, more than 45 million doses of azithromycin

10–30% mass distribution of antibiotics should continue were distributed.8 The total needs to be scaled up by 50%

for 3 years before prevalence is reassessed (appendix).11 for the GET 2020 targets to be achieved (figure 4).

The decision to treat for 3 years is supported by a recent Azithromycin is expensive and mass distribution is only

randomised controlled trial in which mass distribution cost effective because of Pfizer’s continuing large-scale

would be stopped in low-prevalence Tanzanian donation programme.86 Because of overlapping geo-

communities (10–20%) if C trachomatis detection (not graphical distribution, integration of mass distribution of

the rate of clinical TF) dropped below 5% before the antibiotics for trachoma and that for other neglected

www.thelancet.com Vol 384 December 13, 2014 2147

Seminar

A Model for surgery scale-up B Model for antibiotics scale-up

4500 Patients 750 120 People 80

People remaining in endemic areas (millions)

Operations Doses

Patients awaiting surgery (thousands)

4000

Doses distributed per year (millions)

Operations per year (thousands)

100

3500 60

3000 500 80

2500

60 40

2000

1500 250 40

1000 20

20

500

0 0 0 0

2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020

Year Year

Figure 4: Projected needs for trichiasis surgery and antibiotic distribution to eliminate trachoma in know endemic districts8

tropical diseases has been suggested.126 Little evidence is by 6 months and resistance could soon disappear in the

available on the coadministration of azithromycin with absence of further antibiotic distribution.

other drugs, and trials are underway. Mass distribution

programmes can be integrated by staggering the delivery Facial cleanliness and environmental improvements

of drugs over time. Since 2009, more than 30 million Although much attention is given to mass distribution

people have been treated in Mali without severe adverse of antibiotics and surgery, any surgical and antibiotic

reactions.127 Modelling showed that neither targeted programme should address the root cause of trachoma

treatment of households nor targeted treatment of and be accompanied by facial cleanliness campaigns

screened individuals was more cost effective than mass and efforts to improve health hardware that will enable

distribution if donated azithromycin continued.86,128 The facial cleanliness. If the basic hygiene factors that

success of mass distribution of antibiotics is related to allowed trachoma to thrive in the first place are not

coverage; WHO recommends coverage of 100%,11 with a addressed, it will return once mass distribution of

minimum coverage of 90% of total population.129 antibiotics ceases.

For large-scale mass distribution of antibiotics a very Poor facial cleanliness has been consistently associated

safe drug is needed. Azithromycin has an excellent safety with trachoma6,23,135 and is an important modifiable risk

profile. Mass distribution of azithromycin is reported to factor. Observational studies suggest the importance of

halve childhood mortality130 and to reduce rates of facial cleanliness campaigns.136 A randomised controlled

diarrhoea and respiratory-tract infections.131,132 Antibiotic trial of facial cleanliness showed a significant reduction

resistance is always a concern but macrolide resistance in severe inflammatory trachoma.24 The greatest decrease

was not identified in C trachomatis after four 6-monthly in trachoma in the Sudan was in areas with good uptake

mass treatments.133 Streptococcus pneumoniae develops of both antibiotics and children’s facial cleanliness.137

azithromycin resistance after mass azithromycin Environmental risk factors include water supply, faecal

distribution,134 but because of the fitness cost of main- and refuse disposal, animal pens within households,

taining resistance, rates of resistant bacteria tend to wane and fly density.32,33,41,138 Environmental improvements can

address such risk factors on a community-by-community

basis, although evidence to support this approach is

Search strategy and selection criteria limited. The evidence base for the environmental

We searched the University of Melbourne Discovery Library component of the SAFE strategy is poor.

with the subjects Medicine, Dentistry, and Health Science. In view of the importance of the facial cleanliness and

Databases searched included The University of Melbourne environmental components of the SAFE strategy, the

Library Catalogue, Web of Science (ISI), Scopus version 4 proportion of countries with trachoma that had

(Elsevier), Medline (ISI), CINAHL (EBSCO), and PubMed from implemented these components is disheartening;

Jan 1, 2008, to Dec 31, 2012. We used the search terms although 61% had initiated surgery and antibiotic

“trachoma”, “epidemiology”, or “SAFE strategy” in programmes, only 34% had also implemented facial

combination with “trachomatis”. We have included older key cleanliness and environmental components.139 To increase

and commonly cited publications. Several later review articles the latter activities, trachoma policies should be integrated

and books have been cited as they provide a more expansive into national water, sanitation, hygiene, and child survival

review and references on particular topics. We have also strategies; surgery and antibiotic distribution should be

included web-based reference material for some key areas linked with hygiene and sanitation programmes; and

that are not in the peer-reviewed scientific literature. implementation of hygiene and sanitation programmes

should be included in the monitoring and certification of

2148 www.thelancet.com Vol 384 December 13, 2014

Seminar

elimination.140 However, more evidence is needed on the 8 International Coalition for Trachoma Control. The end in sight—2020

specific contributions of the various environmental INSight. International Coalition for Trachoma Control, 2011. http://

www.trachomacoalition.org/node/713 (accessed Feb 26, 2014).

interventions, their effect on trachoma, and their cost- 9 WHO. Global WHO Alliance for the Elimination of Blinding

effectiveness. Trachoma by 2020. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2012; 87: 161–68.

Trachoma control cannot be maintained without 10 WHO. Trachoma: status of endemicity for blinding trachoma by

country 2013. http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.A1645

appropriate improvements in hygiene and sanitation. (accessed Feb 26, 2014).

Trachoma was eliminated from most developed countries 11 WHO. Report of the 3rd global scientific meeting on trachoma

after access to water, waste disposal, and housing elimination (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland; 19–20

July, 2010). http://www.who.int/blindness/publications/3RDGLOBAL

improved. Such measures provide a useful link between SCIENTIFICMEETINGONTRACHOMA.pdf (accessed Feb 26, 2014).

GET 2020 and general development programmes such 12 Global atlas of trachoma. http://www.trachomaatlas.org (accessed

as the Millennium Development Goals. Feb 26, 2014).

13 WHO. Global Alliance for the Elimination of Blinding Trachoma

by 2020—progress report on elimination of trachoma, 2012.

Conclusion Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2013; 88: 242–51.

The SAFE strategy provides a targeted way to speed up 14 West SK, Muñoz B, Turner VM, Mmbaga BBO, Taylor HR.

the process of a general improvement in living conditions The epidemiology of trachoma in central Tanzania. Int J Epidemiol

1991; 20: 1088–92.

and hygiene that is needed to eliminate trachoma in the

15 Ngondi J, Onsarigo A, Adamu L, et al. The epidemiology of

most disadvantaged areas in the developing world. trachoma in Eastern Equatoria and Upper Nile States, southern

Countries such as Morocco, Ghana, and Oman have Sudan. Bull World Health Organ 2005; 83: 904–12.

eliminated blinding trachoma by use of the strategy.11 16 Ngondi J, Gebre T, Shargie EB, et al. Evaluation of three years of

the SAFE strategy (Surgery, Antibiotics, Facial cleanliness and

Activities at present cover at least half of the world’s Environmental improvement) for trachoma control in five districts

endemic districts, and the mapping of the remainder of Ethiopia hyperendemic for trachoma. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg

2009; 103: 1001–10.

should be completed soon (figures 2, 4).8 As increasing

17 Solomon AW, Holland MJ, Burton MJ, et al. Strategies for control of

resources are brought to bear, the likelihood of eliminating trachoma: observational study with quantitative PCR. Lancet 2003;

blinding trachoma by 2020 becomes stronger. Much work 362: 198–204.

is still needed and more information is needed about the 18 Grassly NC, Ward ME, Ferris S, Mabey DC, Bailey RL. The natural

history of trachoma infection and disease in a Gambian cohort with

use of azithromycin, when to stop mass distribution of frequent follow-up. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2008; 2: e341.

antibiotics, and a better understanding of the progression 19 Taylor HR, Siler JA, Mkocha HA, et al. Longitudinal study of the

of scarring and the treatment of trichiasis. However, we microbiology of endemic trachoma. J Clin Microbiol 1991; 29: 1593–95.

are on the way. 20 Courtright P, Sheppard J, Schachter J, Said ME, Dawson CR.

Trachoma and blindness in the Nile Delta: current patterns and

Contributors projections for the future in the rural Egyptian population.

HW searched the scientific literature; all authors developed, wrote, and Br J Ophthalmol 1989; 73: 536–40.

revised the Seminar. 21 Tabbara KF, al-Omar OM. Trachoma in Saudi Arabia.

Ophthalmic Epidemiol 1997; 4: 127–40.

Declaration of interests

22 Khandekar R, Mohammed AJ. The prevalence of trachomatous

We declare no competing interests.

trichiasis in Oman (Oman eye study 2005). Ophthalmic Epidemiol

Acknowledgments 2007; 14: 267–72.

MB is supported by the Wellcome Trust (grant number 098481/Z12/Z). 23 Taylor HR, Rapoza PA, West S, et al. The epidemiology of infection

in trachoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1989; 30: 1823–33.

References

24 West S, Muñoz B, Lynch M, et al. Impact of face-washing on

1 Stephens RS. Chlamydial evolution: a billion years and counting.

trachoma in Kongwa, Tanzania. Lancet 1995; 345: 155–58.

In: Schachter J, Christiansen G, Clarke IN, et al, eds. Chlamydial

infections—proceedings of the Tenth International Symposium on 25 Abdou A, Munoz BE, Nassirou B, et al. How much is not enough?

Human Chlamydial Infections, June 16–21, 2002, Antalya, Turkey. A community randomized trial of a Water and Health Education

San Francisco: International Chlamydia Symposium, 2002: 3–12. programme for Trachoma and Ocular C trachomatis infection in

Niger. Trop Med Int Health 2010; 15: 98–104.

2 Clarke IN. Evolution of Chlamydia trachomatis. Ann N Y Acad Sci

2011; 1230: E11–18. 26 McCauley AP, Lynch M, Pounds MB, West S. Changing water-use

patterns in a water-poor area: lessons for a trachoma intervention

3 Mariotti SP, Pascolini D, Rose-Nussbaumer J. Trachoma: global

project. Soc Sci Med 1990; 31: 1233–38.

magnitude of a preventable cause of blindness. Br J Ophthalmol

2009; 93: 563–68. 27 Blake IM, Burton MJ, Bailey RL, et al. Estimating household and

community transmission of ocular Chlamydia trachomatis.

4 Taylor HR, Johnson SL, Schachter J, Caldwell HD, Prendergast RA.

PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2009; 3: e401.

Pathogenesis of trachoma: the stimulus for inflammation.

J Immunol 1987; 138: 3023–27. 28 Bailey R, Osmond C, Mabey DCW, Whittle HC, Ward ME. Analysis

of the household distribution of trachoma in a Gambian village

5 Thylefors B, Dawson CR, Jones BR, West SK, Taylor HR. A simple

using a Monte Carlo simulation procedure. Int J Epidemiol 1989;

system for the assessment of trachoma and its complications.

18: 944–51.

Bull World Health Organ 1987; 65: 477–83.

29 Broman AT, Shum K, Munoz B, Duncan DD, West SK.

6 Taylor HR. Trachoma: A blinding scourge from the Bronze Age

Spatial clustering of ocular chlamydial infection over time

to the twenty-first century. Melbourne: Centre for Eye Research

following treatment, among households in a village in Tanzania.

Australia, 2008.

Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2006; 47: 99–104.

7 Kaltenboeck B. Recent advances in the knowledge of animal

30 Congdon N, West S, Vitale S, Katala S, Mmbaga BB. Exposure

chlamydial infections. In: Chernesky M, Caldwell H,

to children and risk of active trachoma in Tanzanian women.

Christiansen G, et al, eds. Chlamydial infections—proceedings of

Am J Epidemiol 1993; 137: 366–72.

the Eleventh International Symposium on Human Chlamydial

Infections, Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, Canada, June 18–23, 31 Emerson PM, Bailey RL, Mahdi OS, Walraven GE, Lindsay SW.

2006. San Francisco: International Chlamydia Symposium, Transmission ecology of the fly Musca sorbens, a putative vector

2006: 399–408. of trachoma. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2000; 94: 28–32.

www.thelancet.com Vol 384 December 13, 2014 2149

Seminar

32 Miller K, Pakpour N, Yi E, et al. Pesky trachoma suspect finally 55 Rasmussen SJ, Eckmann L, Quayle AJ, et al. Secretion of

caught. Br J Ophthalmol 2004; 88: 750–51. proinflammatory cytokines by epithelial cells in response to

33 Emerson PM, Lindsay SW, Alexander N, et al. Role of flies and Chlamydia infection suggests a central role for epithelial cells

provision of latrines in trachoma control: cluster-randomised in chlamydial pathogenesis. J Clin Invest 1997; 99: 77–87.

controlled trial. Lancet 2004; 363: 1093–98. 56 Natividad A, Freeman TC, Jeffries D, et al. Human conjunctival

34 Courtright P, Sheppard J, Lane S, Sadek A, Schachter J, transcriptome analysis reveals the prominence of innate

Dawson CR. Latrine ownership as a protective factor in defense in Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Infect Immun 2010;

inflammatory trachoma in Egypt. Br J Ophthalmol 1991; 75: 322–25. 78: 4895–911.

35 Carlson JH, Porcella SF, McClarty G, Caldwell HD. Comparative 57 Burton MJ, Ramadhani A, Weiss HA, et al. Active trachoma is

genomic analysis of Chlamydia trachomatis oculotropic and associated with increased conjunctival expression of IL17A and

genitotropic strains. Infect Immun 2005; 73: 6407–18. profibrotic cytokines. Infect Immun 2011; 79: 4977–83.

36 Harris SR, Clarke IN, Seth-Smith HM, et al. Whole-genome 58 Abu el-Asrar AM, Geboes K, Tabbara KF, al-Kharashi SA,

analysis of diverse Chlamydia trachomatis strains identifies Missotten L, Desmet V. Immunopathogenesis of conjunctival

phylogenetic relationships masked by current clinical typing. scarring in trachoma. Eye (Lond) 1998; 12: 453–60.

Nat Genet 2012; 44: 413–19, S1. 59 Gall A, Horowitz A, Joof H, et al. Systemic effector and regulatory

37 Hu VH, Holland MJ, Burton MJ. Trachoma: protective and immune responses to chlamydial antigens in trachomatous

pathogenic ocular immune responses to Chlamydia trachomatis. trichiasis. Front Microbiol 2011; 2: 10.

PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013; 7: e2020. 60 Taylor HR. Development of immunity to ocular chlamydial

38 Ngondi J, Ole-Sempele F, Onsarigo A, et al. Blinding trachoma infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1990; 42: 358–64.

in postconflict southern Sudan. PLoS Med 2006; 3: e478. 61 Stephens RS. The cellular paradigm of chlamydial pathogenesis.

39 Wolle MA, Muñoz BE, Mkocha H, West SK. Constant ocular Trends Microbiol 2003; 11: 44–51.

infection with Chlamydia trachomatis predicts risk of scarring 62 Peeling RW, Bailey RL, Conway DJ, et al. Antibody response to the

in children in Tanzania. Ophthalmology 2009; 116: 243–47. 60-kDa chlamydial heat-shock protein is associated with scarring

40 Bobo LD, Novak N, Muñoz B, Hsieh YH, Quinn TC, West S. trachoma. J Infect Dis 1998; 177: 256–59.

Severe disease in children with trachoma is associated with 63 Holland MJ, Bailey RL, Hayes LJ, Whittle HC, Mabey DCW.

persistent Chlamydia trachomatis infection. J Infect Dis 1997; Conjunctival scarring in trachoma is associated with depressed

176: 1524–30. cell-mediated immune responses to chlamydial antigens.

41 West SK, Muñoz B, Lynch M, Kayongoya A, Mmbaga BBO, J Infect Dis 1993; 168: 1528–31.

Taylor HR. Risk factors for constant, severe trachoma among 64 Burton MJ, Bailey RL, Jeffries D, Mabey DCW, Holland MJ.

preschool children in Kongwa, Tanzania. Am J Epidemiol 1996; Cytokine and fibrogenic gene expression in the conjunctivas of

143: 73–78. subjects from a Gambian community where trachoma is endemic.

42 West SK, Muñoz B, Mkocha H, Hsieh YH, Lynch MC. Progression Infect Immun 2004; 72: 7352–56.

of active trachoma to scarring in a cohort of Tanzanian children. 65 Burton MJ, Rajak SN, Bauer J, et al. Conjunctival transcriptome

Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2001; 8: 137–44. in scarring trachoma. Infect Immun 2011; 79: 499–511.

43 Michel CEC, Roper KG, Divena MA, Lee HH, Taylor HR. 66 Darville T, O’Neill JM, Andrews CW Jr, Nagarajan UM, Stahl L,

Correlation of clinical trachoma and infection in Aboriginal Ojcius DM. Toll-like receptor-2, but not Toll-like receptor-4, is

communities. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2011; 5: e986. essential for development of oviduct pathology in chlamydial

44 Ward M, Bailey R, Lesley A, Kajbaf M, Robertson J, Mabey D. genital tract infection. J Immunol 2003; 171: 6187–97.

Persisting inapparent chlamydial infection in a trachoma endemic 67 Natividad A, Hull J, Luoni G, et al. Innate immunity in ocular

community in The Gambia. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl 1990; Chlamydia trachomatis infection: contribution of IL8 and CSF2

69: 137–48. gene variants to risk of trachomatous scarring in Gambians.

45 Smith A, Muñoz B, Hsieh YH, Bobo L, Mkocha H, West S. BMC Med Genet 2009; 10: 138.

OmpA genotypic evidence for persistent ocular Chlamydia trachomatis 68 Natividad A, Cooke G, Holland MJ, et al. A coding

infection in Tanzanian village women. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2001; polymorphism in matrix metalloproteinase 9 reduces risk of

8: 127–35. scarring sequelae of ocular Chlamydia trachomatis infection.

46 Hu VH, Massae P, Weiss HA, et al. Bacterial infection in BMC Med Genet 2006; 7: 40.

scarring trachoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011; 52: 2181–86. 69 Bowman RJC, Faal H, Myatt M, et al. Longitudinal study of

47 Bailey RL, Natividad-Sancho A, Fowler A, et al. Host genetic trachomatous trichiasis in the Gambia. Br J Ophthalmol 2002;

contribution to the cellular immune response to 86: 339–43.

Chlamydia trachomatis: heritability estimate from a Gambian twin 70 Frick KD, Melia BM, Buhrmann RR, West SK. Trichiasis and

study. Drugs Today (Barc) 2009; 45 (suppl B): 45–50. disability in a trachoma-endemic area of Tanzania. Arch Ophthalmol

48 Burton MJ, Holland MJ, Makalo P, et al. Profound and sustained 2001; 119: 1839–44.

reduction in Chlamydia trachomatis in The Gambia: a five-year 71 Dhaliwal U, Nagpal G, Bhatia MS. Health-related quality of life in

longitudinal study of trachoma endemic communities. patients with trachomatous trichiasis or entropion.

PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2010; 4: 1–10. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2006; 13: 59–66.

49 Muñoz B, Bobo L, Mkocha H, Lynch M, Hsieh YH, West S. 72 Yang JL, Schachter J, Moncada J, et al. Comparison of an rRNA-based

Incidence of trichiasis in a cohort of women with and without and DNA-based nucleic acid amplification test for the detection of

scarring. Int J Epidemiol 1999; 28: 1167–71. Chlamydia trachomatis in trachoma. Br J Ophthalmol 2007;

50 Bowman RJC, Jatta B, Cham B, et al. Natural history of 91: 293–95.

trachomatous scarring in The Gambia: results of a 12-year 73 Keenan JD, See CW, Moncada J, et al. Diagnostic characteristics of

longitudinal follow-up. Ophthalmology 2001; 108: 2219–24. tests for ocular Chlamydia after mass azithromycin distributions.

51 el-Asrar AM, Van den Oord JJ, Geboes K, Missotten L, Emarah MH, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012; 53: 235–40.

Desmet V. Immunopathology of trachomatous conjunctivitis. 74 Keenan JD, Ayele B, Gebre T, et al. Ribosomal RNA evidence of

Br J Ophthalmol 1989; 73: 276–82. ocular Chlamydia trachomatis infection following 3 annual mass

52 Abu el-Asrar AM, Geboes K, al-Kharashi SA, Tabbara KF, azithromycin distributions in communities with highly prevalent

Missotten L. Collagen content and types in trachomatous trachoma. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54: 253–56.

conjunctivitis. Eye (Lond) 1998; 12: 735–39. 75 See CW, Alemayehu W, Melese M, et al. How reliable are tests for

53 Hu VH, Weiss HA, Massae P, et al. In vivo confocal microscopy trachoma?—a latent class approach. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;

in scarring trachoma. Ophthalmology 2011; 118: 2138–46. 52: 6133–37.

54 Reacher MH, Pe’er J, Rapoza PA, Whittum-Hudson JA, 76 Lakew T, House J, Hong KC, et al. Reduction and return of

Taylor HR. T cells and trachoma: their role in cicatricial disease. infectious trachoma in severely affected communities in Ethiopia.

Ophthalmology 1991; 98: 334–41. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2009; 3: e376.

2150 www.thelancet.com Vol 384 December 13, 2014

Seminar

77 Keenan JD, Lakew T, Alemayehu W, et al. Slow resolution of 100 Rabiu MM, Abiose A. Magnitude of trachoma and barriers to

clinically active trachoma following successful mass antibiotic uptake of lid surgery in a rural community of northern Nigeria.

treatments. Arch Ophthalmol 2011; 129: 512–13. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2001; 8: 181–90.

78 Munoz B, Stare D, Mkocha H, Gaydos C, Quinn T, West SK. 101 West S, Lynch M, Muñoz B, Katala S, Tobin S, Mmbaga BBO.

Can clinical signs of trachoma be used after multiple rounds Predicting surgical compliance in a cohort of women with

of mass antibiotic treatment to indicate infection? trichiasis. Int Ophthalmol 1994; 18: 105–09.

Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011; 52: 8806–10. 102 Bowman RJ, Soma OS, Alexander N, et al. Should trichiasis surgery

79 Ngondi J, Reacher M, Matthews F, Brayne C, Emerson P. Trachoma be offered in the village? A community randomised trial of village

survey methods: a literature review. Bull World Health Organ 2009; vs health centre-based surgery.Trop Med Int Health 2000; 5: 528–33.

87: 143–51. 103 Rajak SN, Habtamu E, Weiss HA, et al. Why do people not attend

80 International Coalition for Trachoma Control. Global for treatment for trachomatous trichiasis in Ethiopia? A study of

Trachoma Mapping Project—training for mapping of trachoma, barriers to surgery. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2012; 6: e1766.

version 2. International Coalition for Trachoma Control, 2013. 104 Khandekar R, Al-Hadrami K, Sarvanan N, Al Harby S,

http://www.trachomacoalition.org/sites/default/files/uploads/ Mohammed AJ. Recurrence of trachomatous trichiasis 17 years

resources/GTMP_2ndEdition_Web (1).pdf (accessed Feb 26, 2014). after bilamellar tarsal rotation procedure. Am J Ophthalmol 2006;

81 Negrel AD, Taylor HR, West S. Guidelines for the rapid assessment 141: 1087–91.

for blinding trachoma. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2001. 105 Habte D, Gebre T, Zerihun M, Assefa Y. Determinants of uptake

82 Myatt M, Limburg H, Minassian D, Katyola D. Field trial of of surgical treatment for trachomatous trichiasis in North Ethiopia.

applicability of lot quality assurance sampling survey method Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2008; 15: 328–33.

for rapid assessment of prevalence of active trachoma. 106 Alemayehu W, Melese M, Bejiga A, Worku A, Kebede W,

Bull World Health Organ 2003; 81: 877–85. Fantaye D. Surgery for trichiasis by ophthalmologists versus

83 Rajak SN, Collin JRO, Burton MJ. Trachomatous trichiasis and integrated eye care workers: a randomized trial. Ophthalmology

its management in endemic countries. Surv Ophthalmol 2012; 2004; 111: 578–84.

57: 105–35. 107 Rajak SN, Habtamu E, Weiss HA, et al. Epilation for trachomatous

84 Reacher M, Foster A, Huber J. Trichiasis surgery for trachoma— trichiasis and the risk of corneal opacification. Ophthalmology 2012;

the bilamellar tarsal rotation procedure. Geneva: World Health 119: 84–89.

Organization, 1993. 108 West ES, Munoz B, Imeru A, Alemayehu W, Melese M, West SK.

85 Reacher MH, Muñoz B, Alghassany A, Daar AS, Elbualy M, The association between epilation and corneal opacity among eyes

Taylor HR. A controlled trial of surgery for trachomatous trichiasis with trachomatous trichiasis. Br J Ophthalmol 2006; 90: 171–74.

of the upper lid. Arch Ophthalmol 1992; 110: 667–74. 109 Rajak SN, Habtamu E, Weiss HA, et al. Surgery versus epilation

86 Baltussen RM, Sylla M, Frick KD, Mariotti SP. Cost-effectiveness for the treatment of minor trichiasis in Ethiopia: a randomised

of trachoma control in seven world regions. Ophthalmic Epidemiol controlled noninferiority trial. PLoS Med 2011; 8: e1001136.

2005; 12: 91–101. 110 Evans JR, Solomon AW. Antibiotics for trachoma.

87 Burton MJ, Kinteh F, Jallow O, et al. A randomised controlled trial Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; 3: CD001860.

of azithromycin following surgery for trachomatous trichiasis in 111 Atik B, Thanh TTK, Luong VQ, Lagree S, Dean D. Impact of

the Gambia. Br J Ophthalmol 2005; 89: 1282–88. annual targeted treatment on infectious trachoma and susceptibility

88 Woreta TA, Munoz BE, Gower EW, Alemayehu W, West SK. to reinfection. JAMA 2006; 296: 1488–97.

Effect of trichiasis surgery on visual acuity outcomes in Ethiopia. 112 Chidambaram JD, Alemayehu W, Melese M, et al. Effect of a

Arch Ophthalmol 2009; 127: 1505–10. single mass antibiotic distribution on the prevalence of infectious

89 Rajak SN, Habtamu E, Weiss HA, et al. Absorbable versus silk trachoma. JAMA 2006; 295: 1142–46.

sutures for surgical treatment of trachomatous trichiasis in 113 Lee S, Alemayehu W, Melese M, et al. Chlamydia on children

Ethiopia: a randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med 2011; 8: e1001137. and flies after mass antibiotic treatment for trachoma.

90 West SK, West ES, Alemayehu W, et al. Single-dose azithromycin Am J Trop Med Hyg 2007; 76: 129–31.

prevents trichiasis recurrence following surgery: randomized trial 114 House JI, Ayele B, Porco TC, et al. Assessment of herd protection

in Ethiopia. Arch Ophthalmol 2006; 124: 309–14. against trachoma due to repeated mass antibiotic distributions:

91 Khandekar R, Mohammed AJ, Courtright P. Recurrence of a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2009; 373: 1111–18.

trichiasis: a long-term follow-up study in the Sultanate of Oman. 115 Schachter J, West SK, Mabey D, et al. Azithromycin in control of

Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2001; 8: 155–61. trachoma. Lancet 1999; 354: 630–35.

92 Thanh TTK, Khandekar R, Luong VQ, Courtright P. One year 116 Gebre T, Ayele B, Zerihun M, et al. Comparison of annual versus

recurrence of trachomatous trichiasis in routinely operated twice-yearly mass azithromycin treatment for hyperendemic

Cuenod Nataf procedure cases in Vietnam. Br J Ophthalmol 2004; trachoma in Ethiopia: a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2012;

88: 1114–18. 379: 143–51.

93 Burton MJ, Bowman RJC, Faal H, et al. Long term outcome of 117 West SK, Munoz B, Mkocha H, et al. Infection with

trichiasis surgery in the Gambia. Br J Ophthalmol 2005; Chlamydia trachomatis after mass treatment of a trachoma

89: 575–79. hyperendemic community in Tanzania: a longitudinal study.

94 Ezz al Arab G, Tawfik N, El Gendy R, Anwar W, Courtright P. Lancet 2005; 366: 1296–300.

The burden of trachoma in the rural Nile Delta of Egypt: a survey 118 Burton MJ, Holland MJ, Makalo P, et al. Re-emergence of

of Menofiya governorate. Br J Ophthalmol 2001; 85: 1406–10. Chlamydia trachomatis infection after mass antibiotic treatment

95 Rajak SN, Makalo P, Sillah A, et al. Trichiasis surgery in The of a trachoma-endemic Gambian community: a longitudinal study.

Gambia: a 4-year prospective study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2010; Lancet 2005; 365: 1321–28.

51: 4996–5001. 119 Solomon AW, Holland MJ, Alexander NDE, et al. Mass treatment

96 Merbs SL, West SK, West ES. Pattern of recurrence of trachomatous with single-dose azithromycin for trachoma. N Engl J Med 2004;

trichiasis after surgery surgical technique as an explanation. 351: 1962–71.

Ophthalmology 2005; 112: 705–09. 120 Yohannan J, Munoz B, Mkocha H, et al. Can we stop mass

97 West ES, Mkocha H, Munoz B, et al. Risk factors for postsurgical drug administration prior to 3 annual rounds in communities

trichiasis recurrence in a trachoma-endemic area. with low prevalence of trachoma? PRET Ziada trial results.

Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2005; 46: 447–53. JAMA Ophthalmol 2013; 131: 431–36.

98 Zhang H, Kandel RP, Sharma B, Dean D. Risk factors for 121 Solomon AW, Harding-Esch E, Alexander NDE, et al. Two doses

recurrence of postoperative trichiasis: implications for trachoma of azithromycin to eliminate trachoma in a Tanzanian community.

blindness prevention. Arch Ophthalmol 2004; 122: 511–16. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 1870–71.

99 Zhang H, Kandel RP, Atakari HK, Dean D. Impact of oral 122 Melese M, Chidambaram JD, Alemayehu W, et al. Feasibility

azithromycin on recurrence of trachomatous trichiasis in Nepal of eliminating ocular Chlamydia trachomatis with repeat mass

over 1 year. Br J Ophthalmol 2006; 90: 943–48. antibiotic treatments. JAMA 2004; 292: 721–25.

www.thelancet.com Vol 384 December 13, 2014 2151

Seminar

123 West SK, Munoz B, Mkocha H, Gaydos CA, Quinn TC. Number 133 Hong KC, Schachter J, Moncada J, Zhou Z, House J, Lietman TM.

of years of annual mass treatment with azithromycin needed to Lack of macrolide resistance in Chlamydia trachomatis after mass

control trachoma in hyper-endemic communities in Tanzania. azithromycin distributions for trachoma. Emerg Infect Dis 2009;

J Infect Dis 2011; 204: 268–73. 15: 1088–90.

124 Lietman T, Porco T, Dawson C, Blower S. Global elimination 134 Haug S, Lakew T, Habtemariam G, et al. The decline of

of trachoma: how frequently should we administer mass pneumococcal resistance after cessation of mass antibiotic

chemotherapy? Nat Med 1999; 5: 572–76. distributions for trachoma. Clin Infect Dis 2010; 51: 571–74.

125 Biebesheimer JB, House J, Hong KC, et al. Complete local 135 Schémann J-F, Sacko D, Malvy D, et al. Risk factors for trachoma

elimination of infectious trachoma from severely affected in Mali. Int J Epidemiol 2002; 31: 194–201.

communities after six biannual mass azithromycin distributions. 136 Hsieh YH, Bobo LD, Quinn TC, West SK. Risk factors for

Ophthalmology 2009; 116: 2047–50. trachoma: 6-year follow-up of children aged 1 and 2 years.

126 Hotez PJ. Mass drug administration and integrated control for Am J Epidemiol 2000; 152: 204–11.

the world’s high-prevalence neglected tropical diseases. 137 Ngondi J, Onsarigo A, Matthews F, et al. Effect of 3 years of SAFE

Clin Pharmacol Ther 2009; 85: 659–64. (surgery, antibiotics, facial cleanliness, and environmental change)

127 Dembélé M, Bamani S, Dembélé R, et al. Implementing preventive strategy for trachoma control in southern Sudan: a cross-sectional

chemotherapy through an integrated National Neglected Tropical study. Lancet 2006; 368: 589–95.

Disease Control Program in Mali. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2012; 6: e1574. 138 West S, Lynch M, Turner V, et al. Water availability and trachoma.

128 Blake IM, Burton MJ, Solomon AW, et al. Targeting antibiotics to Bull World Health Organ 1989; 67: 71–75.

households for trachoma control. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2010; 4: e862. 139 WHO. Report of the Twelfth Meeting of the WHO Alliance for the

129 West SK, Bailey R, Munoz B, et al. A randomized trial of two Global Elimination of Blinding Trachoma (Geneva, Switzerland).

coverage targets for mass treatment with azithromycin for Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008. http://www.who.int/

trachoma. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013; 7: e2415. entity/blindness/publications/GET12-REPORT-ENG_final.pdf

130 Keenan JD, Ayele B, Gebre T, et al. Childhood mortality in a cohort (accessed Feb 26, 2014).

treated with mass azithromycin for trachoma. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 140 Montgomery MA, Bartram J. Short-sightedness in sight-saving:

52: 883–88. half a strategy will not eliminate blinding trachoma.

131 Fry AM, Jha HC, Lietman TM, et al. Adverse and beneficial Bull World Health Organ 2010; 88: 82.

secondary effects of mass treatment with azithromycin to eliminate

blindness due to trachoma in Nepal. Clin Infect Dis 2002;

35: 395–402.

132 Coles CL, Seidman JC, Levens J, Mkocha H, Munoz B,

West S. Association of mass treatment with azithromycin in

trachoma-endemic communities with short-term reduced risk of

diarrhea in young children. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2011; 85: 691–96.

2152 www.thelancet.com Vol 384 December 13, 2014

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Hasil Stock Opname Primaya Hospital TangerangDocument6 pagesHasil Stock Opname Primaya Hospital Tangerangnurlailaela23No ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Biliary Anatomy Is Extremely VariableDocument6 pagesBiliary Anatomy Is Extremely VariableNurlaila ElaNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Emerald Ward Fall Risk Monitoring SheetDocument2 pagesEmerald Ward Fall Risk Monitoring Sheetnurlailaela23No ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hasil Stock Opname Primaya Hospital TangerangDocument6 pagesHasil Stock Opname Primaya Hospital Tangerangnurlailaela23No ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- In SummaryDocument2 pagesIn SummaryNurlaila ElaNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Sinusitis MastoiditisDocument16 pagesSinusitis Mastoiditisnurlailaela23No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Emerald Ward Fall Risk Monitoring SheetDocument2 pagesEmerald Ward Fall Risk Monitoring Sheetnurlailaela23No ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Biliary Anatomy Is Extremely VariableDocument6 pagesBiliary Anatomy Is Extremely VariableNurlaila ElaNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Data E-Kinerja Non-PNS ShareDocument19 pagesData E-Kinerja Non-PNS Sharenurlailaela23No ratings yet

- Biliary Anatomy Is Extremely VariableDocument6 pagesBiliary Anatomy Is Extremely VariableNurlaila ElaNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- In SummaryDocument2 pagesIn SummaryNurlaila ElaNo ratings yet

- In SummaryDocument2 pagesIn SummaryNurlaila ElaNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- An Overview of Tensorflow + Deep learning 沒一村Document31 pagesAn Overview of Tensorflow + Deep learning 沒一村Syed AdeelNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- AHP for Car SelectionDocument41 pagesAHP for Car SelectionNguyên BùiNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Part I-Final Report On Soil InvestigationDocument16 pagesPart I-Final Report On Soil InvestigationmangjuhaiNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- MN AG v. SANOFI - 3:18-cv-14999 - Defendants' Joint Motion To Dismiss - 2019-08-12Document124 pagesMN AG v. SANOFI - 3:18-cv-14999 - Defendants' Joint Motion To Dismiss - 2019-08-12The Type 1 Diabetes Defense FoundationNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Planning For Network Deployment in Oracle Solaris 11.4: Part No: E60987Document30 pagesPlanning For Network Deployment in Oracle Solaris 11.4: Part No: E60987errr33No ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- ITS America's 2009 Annual Meeting & Exposition: Preliminary ProgramDocument36 pagesITS America's 2009 Annual Meeting & Exposition: Preliminary ProgramITS AmericaNo ratings yet

- Sta A4187876 21425Document2 pagesSta A4187876 21425doud98No ratings yet

- 9780702072987-Book ChapterDocument2 pages9780702072987-Book ChaptervisiniNo ratings yet

- Portable dual-input thermometer with RS232 connectivityDocument2 pagesPortable dual-input thermometer with RS232 connectivityTaha OpedNo ratings yet

- 9IMJan 4477 1Document9 pages9IMJan 4477 1Upasana PadhiNo ratings yet

- Bernardo Corporation Statement of Financial Position As of Year 2019 AssetsDocument3 pagesBernardo Corporation Statement of Financial Position As of Year 2019 AssetsJean Marie DelgadoNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Mba Assignment SampleDocument5 pagesMba Assignment Sampleabdallah abdNo ratings yet

- UKIERI Result Announcement-1Document2 pagesUKIERI Result Announcement-1kozhiiiNo ratings yet

- Tata Group's Global Expansion and Business StrategiesDocument23 pagesTata Group's Global Expansion and Business Strategiesvgl tamizhNo ratings yet

- SD Electrolux LT 4 Partisi 21082023Document3 pagesSD Electrolux LT 4 Partisi 21082023hanifahNo ratings yet

- CORE Education Bags Rs. 120 Cr. Order From Gujarat Govt.Document2 pagesCORE Education Bags Rs. 120 Cr. Order From Gujarat Govt.Sanjeev MansotraNo ratings yet

- Sample Property Management AgreementDocument13 pagesSample Property Management AgreementSarah TNo ratings yet

- 1 Estafa - Arriola Vs PeopleDocument11 pages1 Estafa - Arriola Vs PeopleAtty Richard TenorioNo ratings yet

- PS300-TM-330 Owners Manual PDFDocument55 pagesPS300-TM-330 Owners Manual PDFLester LouisNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Fundamentals of Real Estate ManagementDocument1 pageFundamentals of Real Estate ManagementCharles Jiang100% (4)

- Yamaha Nmax 155 - To Turn The Vehicle Power OffDocument1 pageYamaha Nmax 155 - To Turn The Vehicle Power Offmotley crewzNo ratings yet

- Mayor Byron Brown's 2019 State of The City SpeechDocument19 pagesMayor Byron Brown's 2019 State of The City SpeechMichael McAndrewNo ratings yet

- Pyrometallurgical Refining of Copper in An Anode Furnace: January 2005Document13 pagesPyrometallurgical Refining of Copper in An Anode Furnace: January 2005maxi roaNo ratings yet

- Deed of Sale - Motor VehicleDocument4 pagesDeed of Sale - Motor Vehiclekyle domingoNo ratings yet

- Abra Valley College Vs AquinoDocument1 pageAbra Valley College Vs AquinoJoshua Cu SoonNo ratings yet

- StandardsDocument3 pagesStandardshappystamps100% (1)

- (Free Scores - Com) - Stumpf Werner Drive Blues en Mi Pour La Guitare 40562 PDFDocument2 pages(Free Scores - Com) - Stumpf Werner Drive Blues en Mi Pour La Guitare 40562 PDFAntonio FresiNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Corporate Finance Canadian Canadian 8th Edition Ross Test Bank 1Document36 pagesFundamentals of Corporate Finance Canadian Canadian 8th Edition Ross Test Bank 1jillhernandezqortfpmndz100% (22)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- 3DS MAX SYLLABUSDocument8 pages3DS MAX SYLLABUSKannan RajaNo ratings yet

- Logistic Regression to Predict Airline Customer Satisfaction (LRCSDocument20 pagesLogistic Regression to Predict Airline Customer Satisfaction (LRCSJenishNo ratings yet