Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Von Goom

Uploaded by

Alejandro Corona100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

657 views7 pagesvon gooms gambit short story

Original Title

von goom

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentvon gooms gambit short story

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

657 views7 pagesVon Goom

Uploaded by

Alejandro Coronavon gooms gambit short story

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 7

V̲O̲N̲ ̲G̲O̲O̲M̲'̲S̲ ̲G̲A̲M̲B̲I̲T̲

You won't find Von Goom's Gambit in any of

the books on chess openings. Ludvik Pachman's

Moderne Schachtheorie simply ignores it. Paul

Keres' authoritative work Teoria Debiutow

Szachowych mentions it only in passing in a foot-

note on page 239, advising the reader never to

try it under any circumstances and makes sure

the advice is followed by giving no further infor-

mation. Dr. Max Euwe's Archives lists the gambit

in the index under the initial V. G. (Gambit), but

fortunately gives no page number. The twenty-

volume Chess Encyclopedia (fourth edition) states

that Von Goom is a myth and classifies him with

werewolves and vampires. His Gambit is not men-

tioned. Vassily Nikolayevitch Kryilov heartily rec-

ommends Von Goom's Gambit in the English edi-

tion of his book, Russian Theory of the Opening;

the Russian edition makes no mention of it. For-

tunately Kryilov himself did not—and does not

yet—know the moves, so he did not recommend

them to his American readers. If he had, the cold

war would be finished, and possibly the world.

Von Goom was an inconspicuous man, as

most discoverers usually are; and he probably

made his discovery by accident, as most discov-

erers usually do. He was the illegitimate son of a

well known actress and a prominent political fig-

ure. The scandal of his birth haunted his early

years, and as soon as he could legally do so he

changed his name to Von Goom. He refused to

take a Christian name because he claimed he was

no Christian, a fact which seemed trivial at the

time but was to explain much about this strange

man. He grew fast early in life and attained a

height of five feet four inches by the time he was

ten years old. He seemed to think this height was

sufficient, for he stopped growing. When his

corpse was measured after his sudden demise, it

proved to be exactly five feet four inches. Soon

after he stopped growing, he also stopped talking.

He never stopped working because he never

started. The fortunes of his parents proved suffi-

cient for all his needs. At the first opportunity, he

quit school and spent the next twenty years of his

life reading science fiction and growing a mus-

tache on one side of his face. Apparently, some-

time during this period, he learned to play chess.

On April 5, 1997, he entered his first chess

tournament, the Minnesota State Championship.

At first, the players thought he was a deaf mute

because he refused to speak. Then the tourna-

ment director, announcing the pairings for the

round, made a mistake and announced, "Curt

Brasket—White; Van Goon—Black." A small, cut-

ting voice filled with infinite sarcasm said, "Von

Goom." It was the first time Von Goom had spo-

ken in twenty years. He was to speak once more

before his death.

Von Goom did not win the Minnesota State

Championship. He lost to Brasket in twenty-nine

moves. Then he lost to George Barnes in twenty-

three moves, to K. N. Pedersen in nineteen, Fred-

erick G. Galvin in seven, James Seifert in thirty-

nine, Dr. Milton Jackson (who was five years old

at the time) in one hundred and two. Thereupon,

he retired from tournament chess for two years.

His next appearance was December 12,

1999, in the Greater Birmingham Open, where he

also lost all his games. During the remainder of

the year, he played in the Fresno Chess Festival,

the Eastern States Chess Congress, the Peach

State Invitational and the Alaska Championship.

His score for the year was: opponents forty-one;

Von Goom zero.

Von Goom, however, was determined. For a

period of two and one-half years thereafter he en-

tered every tournament he could. Money was no

obstacle and distance was no barrier. He bought

his own private plane and learned to fly so that he

could travel across the continent playing chess at

every possible occasion. At the end of the two and

one-half year period, he was still looking for his

first win.

Then he discovered his Gambit. The discov-

ery must surely have been by accident, but the

credit—or rather the infamy—of working out the

variations must be attributed to Von Goom. His

unholy studies convinced him that the Gambit

could be played with either the White or the Black

pieces. There was no defense against it. He must

have spent many a terrible night over the chess-

board analyzing things man was not meant to an-

alyze. The discovery of the Gambit and its impli-

cations turned his hair snow white, although his

half mustache remained a dirty brown to his dying

day, which was not far off.

His first opportunity to play the Gambit came

in the Greater New York Open. The pre-

tournament favorite was the wily defending

Champion, grandmaster Miroslav Terminsky, alt-

hough sentiment favored John George Bateman,

the Intercollegiate Champion, who was also all-

American quarterback for Notre Dame, Phi Beta

Kappa and the youngest member of the Atomic

Energy Commission. By this time, Von Goom had

become a familiar, almost comic, figure in the

chess world. People came to accept his silence,

his withdrawal, even his half mustache. As Von

Goom signed his entry card, a few players re-

marked that his hair had turned white; but most

people ignored him. Fifteen minutes after the first

round began, Von Goom won his first game of

chess. His opponent had died of a heart attack.

He won his second game too when his oppo-

nent became violently sick to his stomach after

the first six moves. His third opponent got up

from the table and left the tournament hall in dis-

gust, never to play again. His fourth broke down

in tears, begging Von Goom to desist from playing

the Gambit. The tournament director had to lead

the poor man from the hall. The next opponent

simply sat and stared at Von Goom's opening po-

sition until he lost the game by forfeit.

His string of victories had placed Von Goom

among the leaders of the tournament, and his

next opponent was the Intercollegiate Champion

John George Bateman, a hot-tempered, attacking

player. Von Goom played his Gambit, or if you

prefer to be technical, his Counter Gambit, since

he played the Black pieces. John George's at-

tempted refutation was as unconventional as it

was ineffective. He jumped to his feet, reached

across the table, grabbed Von Goom by the collar

of his shirt and hit him in the mouth. But it did no

good. Even as Von Goom fell, he made his next

move. John George Bateman, who had never

been sick a day in his life, collapsed in an epileptic

fit.

Thus, Von Goom, who had never won a game

of chess in his life before, was to play the wily

grandmaster, Miroslav Terminsky, for the champi-

onship. Unfortunately, the game was shown to a

crowd of spectators on a huge demonstration

board mounted at one end of the hall. The tension

mounted as the two contestants sat down to play.

The crowd gasped in shock and horror when they

saw the opening moves of Von Goom's Gambit.

Then silence descended, a long, unbroken silence.

A reporter who dropped by at the end of the day

to interview the winner found to his amazement

that the crowd and players alike had turned to

stone. Only Terminsky had escaped the holocaust.

The lucky man had gone insane.

A few more like results in tournaments and

Von Goom became, by default, the chess champi-

on of America. As such he received an invitation

to play in the Challengers Tournament, the winner

of which would play a match for the world cham-

pionship with the current champion, Dr. Vladislaw

Feorintoshkin, author, humanitarian and winner of

the Nobel Peace Prize. Some officials of the Inter-

national Chess Federation talked of banning the

Gambit from play, but Von Goom took midnight

journeys to their houses and showed them the

Gambit. They disappeared from the face of the

earth. Thus it appeared that the way to the world

championship stood open for him.

Unknown to Von Goom, however, the night

before he arrived in Portoroz, Yugoslavia, the site

of the tournament, the International Chess Feder-

ation held a secret meeting. The finest brains in

the world gathered together seeking a refutation

to Von Goom's Gambit—and they found it. The

following night, the most intelligent men of their

generation, the leading grandmasters of the

world, took Von Goom out in the woods and shot

him. The great humanitarian Dr. Feorintoshkin

looked down at the body and said, "A merciful end

for Van Goon." A small, cutting voice filled with

infinite sarcasm said, "Von Goom." Then the lead-

ing grandmasters shot him again and cleverly

concealed his body in a shallow grave, which has

not been found to this day. After all, they have

the finest brains in the world.

And what of Von Goom's Gambit? Chess is a

game of logic. Thirty-two pieces move on a board

of sixty-four squares, colored alternately dark and

light. As they move they form patterns. Some of

these patterns are pleasing to the logical mind of

man, and some are not. They show what man is

capable of and what is beyond his reach. Take

any position of the pieces on the chessboard.

Usually it tells of the logical or semi-logical plans

of the players, their strategy in playing for a win

or a draw, and their personalities. If you see a

pattern from the King's Gambit Accepted, you

know that both players are tacticians, that the

fight will be brief but fierce. A pattern from the

Queen's Gambit Declined, however, tells that the

players are strategists playing for minute ad-

vantages, the weakening of one square or the

placing of a Rook on a half-opened file. From such

patterns, pleasing or displeasing, you can tell

much not only about the game and the players

but also about man in general, and perhaps even

about the order of the universe.

Now suppose someone discovers by accident

or design a pattern on the chessboard that is

more than displeasing, an alien pattern that tells

unspeakable things about the mind of a player,

man in general and the order of the universe.

Suppose no normal man can look at such a pat-

tern and remain normal. Surely such a pattern

must have been formed by Von Goom's Gambit.

I wish the story could end here, but I fear it

will not end for a long time. History has shown

that discoveries cannot be unmade. Two months

ago in Camden, New Jersey, a forty-three year

old man was found turned to stone staring at a

position on a chessboard. In Salt Lake City, the

Utah State champion suddenly went screaming

mad. And, last week in Minneapolis, a woman

studying chess suddenly gave birth to twins—

although she was not pregnant at the time.

Myself, I'm giving up the game.

You might also like

- Warhammer FRP - Adv - Dog Eat Dog - 2nd EdDocument17 pagesWarhammer FRP - Adv - Dog Eat Dog - 2nd EdKarl van DieterNo ratings yet

- Mystaran Geography - The MidlandsDocument51 pagesMystaran Geography - The MidlandsJames BarnesNo ratings yet

- Newsun ExcerptDocument5 pagesNewsun ExcerptAsh MaedaevaNo ratings yet

- Beyond The Pit Extra Monster InfoDocument386 pagesBeyond The Pit Extra Monster InfoPaul SavvyNo ratings yet

- Drow Quotes & Common SayingsDocument1 pageDrow Quotes & Common SayingsaodshamankingNo ratings yet

- MP-045 Pet AvengersDocument17 pagesMP-045 Pet AvengersMichael V Galarneau Jr100% (1)

- Beyond The Crystal CaveDocument1 pageBeyond The Crystal CaveMatt WillisNo ratings yet

- Casket Works #1Document36 pagesCasket Works #1arcades666No ratings yet

- Kislev: by Niels Arne Dam, Tim Eccles, and Alfred Nuñez JRDocument12 pagesKislev: by Niels Arne Dam, Tim Eccles, and Alfred Nuñez JRЛазар СрећковићNo ratings yet

- X6 - Quagmire!Document38 pagesX6 - Quagmire!Geo444Geo100% (2)

- Nautical NightsDocument34 pagesNautical NightsJames MarionNo ratings yet

- The City of SpecularumDocument8 pagesThe City of SpecularumsparecrapNo ratings yet

- Dalavash Hrayek: Character Level, Race, & Class ExperienceDocument11 pagesDalavash Hrayek: Character Level, Race, & Class ExperienceAustin ArnoldNo ratings yet

- Last RitesDocument61 pagesLast Ritesanon_946435943No ratings yet

- Meccg 03 HighDocument40 pagesMeccg 03 HighCraigJellyStellyNo ratings yet

- Red Steel - Savage BaroniesDocument118 pagesRed Steel - Savage BaroniesOwen Edwards100% (1)

- Dungeon Magazine - 118-121 Greyhawk Map - GRz9ZbDocument6 pagesDungeon Magazine - 118-121 Greyhawk Map - GRz9Zbwisomi4762No ratings yet

- 3785076Document105 pages3785076matthew_vincent@yahoo.comNo ratings yet

- Space Terrain TilesDocument13 pagesSpace Terrain TilesBrianNo ratings yet

- Misty Mountain HoopDocument15 pagesMisty Mountain HoopJoel BeaversNo ratings yet

- ENG Beasts of NurgleDocument1 pageENG Beasts of NurgleSalvatore BiancaNo ratings yet

- Treasure of SocantriDocument12 pagesTreasure of SocantriartikidNo ratings yet

- AD&D Gnome GnomishkindDocument3 pagesAD&D Gnome GnomishkindI_Niemand100% (1)

- Red Fritz Space 1889 UpdatedDocument3 pagesRed Fritz Space 1889 Updatedhel gramNo ratings yet

- AA WAS Scenario-Campaign Rules Rev2!18!2011Document11 pagesAA WAS Scenario-Campaign Rules Rev2!18!2011David FreitasNo ratings yet

- tsr09147 - The Temple of Elemental Evil-5Document20 pagestsr09147 - The Temple of Elemental Evil-5GarciaNo ratings yet

- The Corrupt Kingdom of Bretonnia - Book4a - ReligionDocument18 pagesThe Corrupt Kingdom of Bretonnia - Book4a - ReligionAlan GatesNo ratings yet

- WFRP Fillable Character Sheet v1.01Document2 pagesWFRP Fillable Character Sheet v1.01Simon Steffensen100% (1)

- Drakkhen ManualDocument44 pagesDrakkhen ManualsacksackNo ratings yet

- (WW) - (RedDeath 02) - Unholy Allies - Robert WeinbergDocument373 pages(WW) - (RedDeath 02) - Unholy Allies - Robert Weinbergdvthorpe100% (1)

- Expendables (Role-Playing Game)Document1 pageExpendables (Role-Playing Game)Ramon Espardena0% (1)

- The Hogfather ScriptDocument4 pagesThe Hogfather ScriptZoe ThorntonNo ratings yet

- Dragon Storm Rules: Gargoyle, Human, Item, Orc, Shaman, Unicorn, Universal, Valarian, Werewolf, Witch, and WizardDocument8 pagesDragon Storm Rules: Gargoyle, Human, Item, Orc, Shaman, Unicorn, Universal, Valarian, Werewolf, Witch, and WizardHeldalelNo ratings yet

- Disk 5Document4 pagesDisk 5api-3830855No ratings yet

- Chapter Fifteen Chapter Fifteen Chapter Fifteen Chapter Fifteen - Warpstone Warpstone Warpstone WarpstoneDocument39 pagesChapter Fifteen Chapter Fifteen Chapter Fifteen Chapter Fifteen - Warpstone Warpstone Warpstone Warpstonebrothersale100% (1)

- Firestorm Armada Critical Hit TableDocument1 pageFirestorm Armada Critical Hit TableSean HoganNo ratings yet

- FIMIRDocument13 pagesFIMIRRorkror100% (3)

- Return To Kalidus: The CampaignDocument4 pagesReturn To Kalidus: The CampaignRobLeeNo ratings yet

- Cavern of The Sub-TrainDocument8 pagesCavern of The Sub-TrainJohn Allmon JamiesonNo ratings yet

- Dragon Magazine Monsters (Incomplete)Document5 pagesDragon Magazine Monsters (Incomplete)ifold100% (1)

- Iii. Briefings For Players: The Treasure of Socantri, Page 1Document9 pagesIii. Briefings For Players: The Treasure of Socantri, Page 1Tracy BloomNo ratings yet

- Fill Able Character SheetDocument5 pagesFill Able Character SheetEric Paul DeSmetNo ratings yet

- Stormbringer - 5th Ed - Old Hrolmar A Visitors GuideDocument7 pagesStormbringer - 5th Ed - Old Hrolmar A Visitors GuideCristina Bosco BoscoNo ratings yet

- Dungeon Master 'S Screen PDFDocument10 pagesDungeon Master 'S Screen PDFbumberto19No ratings yet

- Zzap 640001 HiDocument140 pagesZzap 640001 HialvincardonaNo ratings yet

- Papai NoelDocument2 pagesPapai NoelGuilherme RochaNo ratings yet

- IymrithDocument6 pagesIymrithGustavo PalmeiraNo ratings yet

- TSR 11360 The Created PDFDocument98 pagesTSR 11360 The Created PDFCharles WestonNo ratings yet

- Eberron Campaign Setting ErrataDocument3 pagesEberron Campaign Setting ErrataLivio Quintilio GlobuloNo ratings yet

- The Longest Game: The Five Kasparov/Karpov Matches for the World Chess ChampionshipFrom EverandThe Longest Game: The Five Kasparov/Karpov Matches for the World Chess ChampionshipNo ratings yet

- The Last Gamesman: My Sixty Years of Hustling Games in the Clubs, Parks and Streets of New YorkFrom EverandThe Last Gamesman: My Sixty Years of Hustling Games in the Clubs, Parks and Streets of New YorkNo ratings yet

- Sir Walter: Walter Hagen and the Invention of Professional GolfFrom EverandSir Walter: Walter Hagen and the Invention of Professional GolfRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- The Theory And Practice Of Gamesmanship; Or, The Art Of Winning Games Without Actually CheatingFrom EverandThe Theory And Practice Of Gamesmanship; Or, The Art Of Winning Games Without Actually CheatingRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (35)

- CopyofStructuredAcademicControversy NewDealDocument2 pagesCopyofStructuredAcademicControversy NewDealAlejandro Corona100% (1)

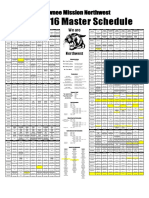

- Master 15-16 Lamourie1Document1 pageMaster 15-16 Lamourie1Alejandro CoronaNo ratings yet

- 18 The Stranger WithinDocument25 pages18 The Stranger WithinAlejandro Corona100% (4)

- 09 The Traitors LodgeDocument28 pages09 The Traitors LodgeAlejandro Corona100% (4)

- 14 Day of The Demon 1Document26 pages14 Day of The Demon 1Alejandro Corona100% (2)

- SJG37-2609 - Pyramid #3-9 - Space Opera PDFDocument44 pagesSJG37-2609 - Pyramid #3-9 - Space Opera PDFJMMPdos100% (2)

- 19 The Horn of ArodenDocument24 pages19 The Horn of ArodenAlejandro Corona100% (2)

- 21 The Merchants WakeDocument26 pages21 The Merchants WakeAlejandro Corona100% (3)

- 23 Cairn of ShadosDocument21 pages23 Cairn of ShadosAlejandro Corona100% (2)

- 1509 5292 1 PBDocument15 pages1509 5292 1 PBAlejandro CoronaNo ratings yet

- 24 Assault On The WoundDocument34 pages24 Assault On The WoundAlejandro Corona100% (3)

- 99 The Paths We ChooseDocument44 pages99 The Paths We ChooseAlejandro Corona100% (4)

- 2.1 Iso Sketches CirclesDocument1 page2.1 Iso Sketches CirclesAlejandro CoronaNo ratings yet

- 12 Destiny of The Sands Part 1 A Bitter BargainDocument24 pages12 Destiny of The Sands Part 1 A Bitter BargainAlejandro Corona100% (2)

- ChipDocument2 pagesChipAlejandro CoronaNo ratings yet

- 1.8 Inst Challenge PaperBridgeDocument2 pages1.8 Inst Challenge PaperBridgeAlejandro CoronaNo ratings yet

- 1Document7 pages1Alejandro CoronaNo ratings yet

- 2nd Law Lab Graph 2Document1 page2nd Law Lab Graph 2Alejandro CoronaNo ratings yet

- ChipDocument2 pagesChipAlejandro CoronaNo ratings yet

- ChipDocument2 pagesChipAlejandro CoronaNo ratings yet

- ChipDocument2 pagesChipAlejandro CoronaNo ratings yet

- ChipDocument2 pagesChipAlejandro CoronaNo ratings yet

- ChipDocument2 pagesChipAlejandro CoronaNo ratings yet

- Thermodynamic Processes: Analysis of Thermodynamic Processes by Applying 1 & 2 Law of ThermodynamicsDocument10 pagesThermodynamic Processes: Analysis of Thermodynamic Processes by Applying 1 & 2 Law of Thermodynamicsmohdmehrajanwar1860No ratings yet

- MDFDocument3 pagesMDFKryzel Anne RamiscalNo ratings yet

- LR (0) Parse AlgorithmDocument12 pagesLR (0) Parse AlgorithmTanmoy MondalNo ratings yet

- Geometric Group Theory NotesDocument58 pagesGeometric Group Theory NotesAllenNo ratings yet

- 7 2 Using FunctionsDocument7 pages7 2 Using Functionsapi-332361871No ratings yet

- Clmd4ageneralmathematicsshs - PDF Function (Mathematics) FormulaDocument1 pageClmd4ageneralmathematicsshs - PDF Function (Mathematics) FormulaNicole Peña TercianoNo ratings yet

- Swan SoftDocument90 pagesSwan Softandreeaoana45No ratings yet

- MMC 2006 Gr5 Reg IndDocument1 pageMMC 2006 Gr5 Reg IndAhrisJeannine EscuadroNo ratings yet

- The Hydrogen AtomDocument15 pagesThe Hydrogen AtomVictor MarchantNo ratings yet

- VTU ThermodynamicsDocument2 pagesVTU ThermodynamicsVinay KorekarNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9 Traffic FlowDocument3 pagesChapter 9 Traffic FlowMatthew DelgadoNo ratings yet

- Block Cipher PrinciplesDocument5 pagesBlock Cipher PrinciplesSatya NarayanaNo ratings yet

- Matlab - An Introduction To MatlabDocument36 pagesMatlab - An Introduction To MatlabHarsh100% (2)

- 1978 Katz Kahn Psychology of OrganisationDocument23 pages1978 Katz Kahn Psychology of OrganisationNisrin Manz0% (1)

- Capacity of A PerceptronDocument8 pagesCapacity of A PerceptronSungho HongNo ratings yet

- 9958Document15 pages9958XiqiangWuNo ratings yet

- Hamming CodeDocument3 pagesHamming CodeKiran KumarNo ratings yet

- Computer Architecture I: Digital DesignDocument89 pagesComputer Architecture I: Digital DesignJitendra PatelNo ratings yet

- Data Visualization Tech.Document6 pagesData Visualization Tech.Abinaya87No ratings yet

- 2020 Past PaperDocument10 pages2020 Past PaperJoshua KimNo ratings yet

- 10mat Beta Textbook 2 AnswersDocument413 pages10mat Beta Textbook 2 AnswersRaymond WangNo ratings yet

- Self Test: Mathematics (Part - 1) Std. X (Chapter 3) 1Document3 pagesSelf Test: Mathematics (Part - 1) Std. X (Chapter 3) 1Umar100% (1)

- Mtec Ece-Vlsi-Design 2018Document67 pagesMtec Ece-Vlsi-Design 2018jayan dNo ratings yet

- DSP-Chapter3 Student 08022017Document49 pagesDSP-Chapter3 Student 08022017Thành Vinh PhạmNo ratings yet

- Fisher Fieldvue DVC6200f Digital Valve Controller For F ™ FieldbusDocument314 pagesFisher Fieldvue DVC6200f Digital Valve Controller For F ™ Fieldbus586301No ratings yet

- Real GasDocument8 pagesReal GasAmartya AnshumanNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal 1 PDFDocument5 pagesResearch Proposal 1 PDFMunem BushraNo ratings yet

- Digital Logic Circuits Objective QuestionsDocument9 pagesDigital Logic Circuits Objective Questionssundar_mohan_2100% (2)

- Curriculum Vitae Suresh B SrinivasamurthyDocument22 pagesCurriculum Vitae Suresh B Srinivasamurthybs_suresh1963No ratings yet

- Maths Difficulties For High School StudentsDocument65 pagesMaths Difficulties For High School StudentsNeha KesarwaniNo ratings yet