Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Kloeckl, Kristian - The Urban Improvise

Uploaded by

Omega Zero100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

61 views15 pagesThe nature of the built environment in today’s hybrid cities has changed radically. Vast networks of mobile and embedded devices that sense, compute, and actuate can enable active as well as interactive behavior that goes beyond planned and scripted routines and that is capable of changing and adapting in a dynamic context. In this article, I draw a parallel between this dynamic and improvisation in the performing arts. I look at improvisation not so much as doing something in a makeshift manner, but rather as a process characterized by a simultaneity of conception and action, where iterative and recursive operations lead to the emergence of dynamic structures that continue to feed into the action itself. An improvisation-based perspective is a compelling way to better understand the design of interaction in the context of today’s hybrid cities.

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe nature of the built environment in today’s hybrid cities has changed radically. Vast networks of mobile and embedded devices that sense, compute, and actuate can enable active as well as interactive behavior that goes beyond planned and scripted routines and that is capable of changing and adapting in a dynamic context. In this article, I draw a parallel between this dynamic and improvisation in the performing arts. I look at improvisation not so much as doing something in a makeshift manner, but rather as a process characterized by a simultaneity of conception and action, where iterative and recursive operations lead to the emergence of dynamic structures that continue to feed into the action itself. An improvisation-based perspective is a compelling way to better understand the design of interaction in the context of today’s hybrid cities.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

61 views15 pagesKloeckl, Kristian - The Urban Improvise

Uploaded by

Omega ZeroThe nature of the built environment in today’s hybrid cities has changed radically. Vast networks of mobile and embedded devices that sense, compute, and actuate can enable active as well as interactive behavior that goes beyond planned and scripted routines and that is capable of changing and adapting in a dynamic context. In this article, I draw a parallel between this dynamic and improvisation in the performing arts. I look at improvisation not so much as doing something in a makeshift manner, but rather as a process characterized by a simultaneity of conception and action, where iterative and recursive operations lead to the emergence of dynamic structures that continue to feed into the action itself. An improvisation-based perspective is a compelling way to better understand the design of interaction in the context of today’s hybrid cities.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 15

The Urban Improvise

Kristian Kloeckl

The nature of the built environment in today’s hybrid cities has

changed radically. Vast networks of mobile and embedded devices

that sense, compute, and actuate can enable active as well as inter-

active behavior that goes beyond planned and scripted routines

and that is capable of changing and adapting in a dynamic context.

In this article, I draw a parallel between this dynamic and impro-

visation in the performing arts. I look at improvisation not so

much as doing something in a makeshift manner, but rather as a

process characterized by a simultaneity of conception and action,

where iterative and recursive operations lead to the emergence of

dynamic structures that continue to feed into the action itself. An

improvisation-based perspective is a compelling way to better

understand the design of interaction in the context of today’s

hybrid cities.

I begin by looking at the relationship between improvisa-

tion and urban life before examining the nature of improvisation

in more detail. By drawing on material from the practice and study

of improvisation in the performing arts, as well as the humanities

and social sciences, I propose four key positions as foundational

elements in an improvisation-based model of urban interaction

design: (1) Design for initiative ensures openness; (2) awareness of

time ensures the relevance of actions; (3) forms of action are under-

stood in the making; and (4) interactions themselves are other than

expected. I then provide a brief analysis of three existing projects

to illustrate how elements of an improvisation-based perspective

on interaction are currently being explored in the field and how

they relate to the key positions of the proposed model. Finally, I

conclude by using responsive urban lighting to illustrate how

improvisation techniques, such as Viewpoints, can be used to put

into action the proposed key positions guiding the design of

responsive urban environments.

Responsive Environments in Hybrid Cities

1 A recent study of this phenomenon at a

global scale can be found here: Depart-

Cities have become a major focus for design research and practice,

ment of Economic and Social Affairs and although many factors explain why the spotlight is on cities,

Population Division, World Urbanization two of these stand out. The first is that ongoing urbanization has

Prospects: The 2014 Revision (New York: led to a concentration of the world’s population in urban agglom-

United Nations, 2015). The report indi-

erations: More than half the world population now lives in cities.1

cates that 54% of the world’s population

resided in urban areas in 2014. This

figure was 30% in 1950 and is projected

to be 66% by 2050.

© 2017 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

44 DesignIssues: Volume 33, Number 4 Autumn 2017 doi: 10.1162/DESI_a_00460

To work on urban issues now means to affect the lives of more

people than ever before. The second is that cities represent a high

density of technology systems related to telecommunications,

transportation, and utilities, among others. These systems are

increasingly connected, exchanging information in real time, and

they represent an opportunity for the design of new approaches to

address urban issues and to engage citizens in the process.2

The increasing pervasiveness of embedded and mobile con-

2 Note two projects that leverage net- nected devices has transformed the built environment from a pre-

worked urban technologies to foster dominantly stable and enduring background for human activity

citizen engagement: (1) PlaceTalk into spaces and objects that have a more fluid behavior. 3 These

(Kloeckl, Cantrell), a project developed

objects and environments are capable of sensing, computing, and

for the Boston Public Space Invitational,

is a series of responsive sculptural acting in real-time; they can change their behavior in response to

objects that bring hyper-local conversa- their own system state, histories of past actions and interactions,

tions to public places by vocalizing a the behavior of humans and machines within their reach, and

wide array of data and information. environmental conditions.

The goal is to develop a conversation

Augmented environments of this type have the potential to

between individuals within the neighbor-

hood and the fleeting information that go beyond simple action–reaction couplings and become truly

makes these communities unique. interactive,4 displaying a dynamic and responsive behavior that

Because much of our daily conversations engages with their human counterparts. Activity is detected and

has moved to online environments, this interpreted, actions are modulated, and behavior is adapted in

project seeks to bring these conversa-

response to unforeseen situations in feedback loops and a continu-

tions back into the public spaces of cities

and, in particular, to the spaces outside ous give and take—all resembling an improvisational perfor-

public library branches. See www.infor- mance. In this article, I take a closer look at the practice and study

mationinaction.com/placetalk (accessed of improvisation to inform the design of interactive artifacts, sys-

March 14, 2017). (2) The Traffic Check tems, and environments in the context of today’s cities.

platform, implemented in Graz (Austria),

enables citizens to provide feedback on

their experience with the signaling con- Models of Interaction: From Interface to Improvisation

trols of traffic lights. The city uses the An interface is an effective conceptual model to contemplate on

feedback to better calibrate the signals human–product interactions, especially when configurations are

for a better experience by all transport fixed (e.g., via sliders, levers, and dials). However, the plasticity of

groups (e.g., pedestrian, bike, car, and

the nature of human–computer interfaces has led to the develop-

public transport), bringing citizens back

into the loop to “control the controls.” ment of alternative models for conceptualizing interaction upon

See https://www.trafficcheck.at/graz/ which the model I propose in this article builds.

(accessed March14, 2017). The notion of conversation as a model for interaction

3 A discussion of this changing condition of dates back to the 1970s, when Gordon Pask generated his work on

the built urban environment can be found

conversation theory. It has been used extensively (e.g., by Ranulph

in Malcolm McCullough, Digital Ground:

Architecture, Pervasive Computing, and

Glanville and Hugh Dubberly, among others) and has recently

Environmental Knowing (Cambridge, MA: garnered much attention in the form of so-called conversational

The MIT Press, 2005), 47–64. interfaces. The notion of common ground as a framework for

4 Dubberly, Pangaro, and Haque make a human–computer interaction (HCI) is based on Herbert Clark’s

clear distinction between different kinds

work in communication theory in the 1990s. Both these notions

of interaction (e.g., reacting, learning,

conversing, collaborating, designing)

suggest models where meaning is negotiated and co-created

and provide a more rigorous definition of

the term that goes beyond its common

notions. See Hugh Dubberly, Paul

Pangaro, and Usman Haque, “What Is

Interaction? Are There Different Types?”

Interactions 16, no. 1 (2009), 69–75.

DesignIssues: Volume 33, Number 4 Autumn 2017 45

between humans and computers through interactions. In this

sense interface is no longer a simple notion by which humans and

computers represent themselves to one another. Rather, it forms a

shared context for action in which both are agents in an Aristote-

lian sense. 5 Brenda Laurel’s model of interface as staged theater,

first published in 1991, was updated and re-edited in 2014; Don

Norman states in the foreword to the latter that “the first edition

was ahead of its time. This new edition comes at just the right time.

Now the world is ready.”6 Theater is presented as a model for the

performance of intentional activity in which both human and com-

puter have a role, concerned with representing whole actions that

involve multiple agents.7

Although this conceptual model opens up fascinating new

ground, it refers only to scripted theater. And in scripted theater,

unlike real life, the process of choice and decision making takes

place during rehearsal and practice, before the actual staging of

the performance. In the sense that drama formulates the enact-

ment and not the action, it is unlike real life. Instead, in improvisa-

tional techniques, as in real life, anything can happen. Actions are

situated in a unique context that is always in flux, and the focus is

on dynamic choice in a dynamic environment. By identifying the

interactions in and with urban responsive environments and the

art of improvisation as fundamentally related topics of investiga-

tion, we can identify a set of underlying positions that point

toward a foundational model for urban interaction design and that

can provide a framework by which interactive urban systems

might be more systematically understood.

Improvisation and the City

Improvisation and public life in cities have always been inter-

twined throughout. A prominent historic tie is that of the Comme-

dia dell’Arte performances that date back to the sixteenth century in

cities of the Italian peninsula. Commedia dell’Arte (see Figure 1) was

5 Discussions of Aristotle’s notion of agent the first professional form of actor groups—a traveling business

as being one who takes action (laid out in enterprise, based on improvisation. Based on a schema or scenario,

his Poetics and Metaphysics) are numer- actors would do away with a script and improvise their perfor-

ous; my main references are Hannah

mances for a number of reasons: Improvisation allowed the perfor-

Arendt, The Human Condition (Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, 1998 [1958]), mance to be adapted to the many local languages and dialects of

7–17, 187; and more specifically in the the peninsula; the story could be adapted up to the last minute to

context of design, Brenda Laurel, Com- embrace current local events and the political situation; and by not

puters as Theatre (Boston: Addison-Wes- being limited to written scripts, performers were not prone to

ley Professional, 2013 [1991]), 71–73;

political censorship.

and Richard Buchanan, “Rhetoric,

Humanism, and Design,” in Discovering

Design, ed. Richard Buchanan and Victor

Margolin (Chicago: The University of

Chicago Press, 1995).

6 Don Norman, “Foreword,” in Laurel,

Computers as Theatre, xii.

7 Laurel, Computers as Theatre, 11.

46 DesignIssues: Volume 33, Number 4 Autumn 2017

Figure 1 The subversive nature of acting-in-the-moment is also what

Commedia dell’arte Scene in an Italian Michel de Certeau describes in The Practice of Everyday Life, when

Landscape, by Peeter van Bredael, 17th/18th he focuses on the innumerable “ways of operating,” the everyday

century. Image is in the public domain. tactics, by means of which users reappropriate space organized by

powerful strategies and techniques of sociocultural production.8

De Certeau looks at how people take shortcuts between formally

proposed paths; what people actually do with systems put in place

for them to consume; and what clandestine forms of practices and

procedures of everyday interactions exist relative to structures of

expectation, negotiation, and improvisation.

Today, visions of the city are frequently described as an

entity that functions akin to a computer—“The city itself is turn-

ing into a constellation of computers”9—numerically controlled

and on a binary basis. However, this image somehow does not

always resemble the motives behind people’s choice to move to cit-

8 Michel De Certeau, The Practice of ies in the first place. “We move to what are essentially idea facto-

Everyday Life (Berkeley: University of ries: cities full of people,” affirms Enrico Moretti.10 Many people

California Press, 2011). move to cities for something that exceeds their expectation—a

9 Michael Batty, “The Computable City,”

search for the unexpected and for the unforeseen.

International Planning Studies 2, no. 2

(1997), 155.

10 Kevin Maney, “Why Millennials Still

Move to Cities,” Newsweek, Mar. 30,

2015. http://www.newsweek.com/

2015/04/10/why-cities-hold-more-

pull-millennials-cloud-317735.html

(accessed January 25, 2017).

DesignIssues: Volume 33, Number 4 Autumn 2017 47

On Improvisation as a System

This reasoning points in fact to the very notion of improvisation:

Its Latin root proviso indicates a condition attached to an agree-

ment, a stipulation made beforehand. Im-provisation, then, indi-

cates that which has not been agreed on or planned and thus

presents itself as unforeseen and unexpected. However, improvisa-

tion is a process that is often misunderstood. A common interpre-

tation is that when something is improvised, it is to make up for

the lack of something, or to get by in some way until the plan that

was lost can be recovered.11 The view of improvisation that I adopt

goes beyond this interpretation.

In the context of music, improvisation refers to playing in

the moment, or composing in the flow. It is a process characterized

by a simultaneity of both conception and presentation12; and dur-

ing the act of execution, the situation at hand continues to feed into

what is being played. To talk about improvisation also means to

consider the notion of inventiveness, involving elements both of

novelty and of repetition of past patterns.13 We can “conceive of

improvisation as an iterative and recursively operating process

where dynamic structures emerge from the processing and repro-

11 Alfonso Montuori, “The Complexity cessing of elements.”14 With this understanding, we capture more

of Improvisation and the Improvisation

of the essence of the practice, which enables us to identify struc-

of Complexity: Social Science, Art and

Creativity,” Human Relations 56, no. 2 tures in a process that can at first appear ephemeral.

(2003): 237–55. We typically underestimate the investment in attention,

12 Edgar Landgraf, Improvisation as Art: study, and practice that is the foundation for every improvised

Conceptual Challenges, Historical performance. Requiring a heightened awareness both of self and of

Perspectives (New York: Bloomsbury

others, an improvisation is based to a critical extent on the artist’s

Academic, 2014), 16.

13 The debate on the possibility or impossi-

past practice and experience. When artists improvise, they elabo-

bility of true originality is longstanding. rate on existing material in relation to the unforeseen ideas that

Immanuel Kant defines a genius as one emerge out of the context and the unique conditions of the perfor-

who is capable of the utmost original act, mance. In this way, variations are created and new features are

free from all that was before, disrupting

added every time, making all performances distinct.15 Improvisa-

any previous convention or norm in his

Critique of Judgment (Oxford: Clarendon

tion overcomes several dichotomies instilled by modern thought.

Press, 1952), 181. In contrast, Jacques Its practice overcomes clear distinctions between repetition and

Derrida talks about the impossibility novelty, discipline and spontaneity, security and risk, individual

of total originality because of an and group, and ultimately, order and disorder. It does so by doing

ever-present repetition of the past in

away with a binary opposition and embracing a mind frame of

his Psyche: Inventions of the Other, in

Waters and Godzich, Reading de Man

complexity, in which order and disorder—information and noise—

Reading (Minneapolis: University of form a mutually constitutive relationship.16

Minnesota Press, 1989). In improvisation many actions do not receive their full

14 Landgraf, Improvisation as Art, 36. meaning until after the act has occurred. What one actor does will

15 Paul F. Berliner, Thinking in Jazz: The

redefine the meaning of the previous action of another actor,

Infinite Art of Improvisation (Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, 1994), 222;

which again will be conditioned by the following action. These

Karl E Weick, “Introductory Essay— recursive processes define themselves because their definition

Improvisation as a Mindset for Organiza-

tional Analysis,” Organization Science 9,

no. 5 (1998): 543–55.

16 Montuori, “The Complexity of Improvisa-

tion,” 241.

48 DesignIssues: Volume 33, Number 4 Autumn 2017

cannot be attributed to the intention of a single or even all partic-

ipating actors. In systems theory, emergence describes the appear-

ance of something new that could not be anticipated but that was

born out of the interaction between previously present elements.

Adapting a systems view of improvisation makes the tension

between the notions of stability and variation a productive one.

Key Positions for an Improvisation-Based Model of Design

Looking at improvisation as a system can help to identify a

number of key positions that are recurrent in different types of

improvisation. I propose four foundational elements for an impro-

visation-based model of urban interaction design:

Design for Initiative Ensures Openness

A critical aspect of improvisational performance involves the

beginnings—and as such, the notions of agency and autonomy of a

person or system. Who starts? When? And how? Because no plan

exists, the beginning of an action is born out of context and out of

initiative. Making a first move, speaking the first word, taking the

initiative, represents a marking of an unmarked space.17 However,

improvisation is not so much about creating or maintaining any

one particular work; rather, it is about ensuring an openness

toward a process of ongoing creation.18 Keeping the improvisation

going upstages any structure that might emerge during the pro-

cess. Designing responsive systems in this sense, then, implies

17 Peters, referring to Niklas Luhmann in viewing any process of interaction as something that has already

Gary Peters, The Philosophy of Improv-

begun and that will continue beyond a specific instance of interac-

isation (The University of Chicago Press,

2012), 12. tion while fostering openings for initiative.

18 Heidegger describes the triangular

relation between the artist, the artwork, Awareness of Time Ensures the Relevance of Actions

and art: The artist makes the artwork, but Time and timing are key in improvisation. Planning and action

also the artwork, once conceived, makes

collapse into a single moment, and the configuration of content in

the artist. And they both exist only in

virtue of a prior notion of art itself. This time and space molds the meaning of action. Timing here refers to

existential interdependence ensures that the relationship between one moment of change and the next, and

the creative act is not a single act but the awareness of time in improvisation ensures the relevance of

the beginning of a process—a process actions. Through the experience of time—when you do something,

that ties the artist to the working of the

when you don’t, when you start, when you stop—you realize that

work rather than to any one particular

piece of art that may be generated. you have a choice. You start, you stop. You change. You determine

Martin Heidegger, “The Origin of the your experience.19 A design approach informed by this position

Work of Art” Poetry, Language, Thought attributes more relevance to felt time and event time. Rather than

55 (1971), 17–79. chronos—achronological, sequential, and quantitative time—the

19 For an in-depth discussion of aspects

notion of kairos comes into play—a qualitative understanding of

of time and timing in Action Theatre

improvisation, see Ruth Zaporah, Action time. Kairos points toward a time lapse, a passing moment of unde-

Theatre: The Improvisation of Presence termined time in which everything happens, and the opportune

(North Atlantic Books, 1995), 9. Zaporah or right moment when an opening appears for a committed action

is the founder of Action Theatre. of opportunity.20

20 Eric Charles White, Kaironomia: On

the Will-to-Invent (Ithaca, NY: Cornell

University Press, 1987), 3.

DesignIssues: Volume 33, Number 4 Autumn 2017 49

Forms of Action Are Understood in the Making

In ensemble work, each performer feeds off and builds on what

others do. As they interact with each other, performers pass cues

back and forth, consciously or unconsciously. They are perceived

and interpreted, and whether they are interpreted in the intended

way matters less. They become part of a collective creation of

meaning that informs the interaction. Not only do improvisational

performers pick up on gestures, on sequences played and acted by

their fellow performers, they also develop a capability to recognize

form when it is in the making—attributing meaning to the com-

pleted form of which they see the seed. The attributed meaning

and the action based on it become the novel element an actor con-

tributes to the collective process, regardless of whether the original

action was executed toward that expectation or not.

In the design of urban interactions, this ability to recognize

form in the making puts the focus on cues and indexicality of ges-

ture and behavior. As responsive environments detect and inter-

pret human behavior, system adjustments made in response are

interpreted at their onset by the very people that condition the

change. In such a feedback loop, an important role falls to the sys-

tem’s accountability—the ways in which any responsive system or

artifact is “observable and reportable” by a person who can, to

some extent, make sense of an action in context to support interac-

tion in a constantly changing environment.21 Misunderstandings

and errors are constructive parts in this process. They are the noise

that leads to the emergence of new structures.

Interactions Themselves Are Other than Expected

In its unplanned and in-the-moment nature, improvisation deals

with the unexpected and the uncontrollable—that which cannot be

fully known and that is Other from what we know. Our culture has

taught us to label the autonomy and Otherness of things and crea-

tures around us as wild. In “The Trouble with Wilderness,” Wil-

liam Cronon juxtaposes wildness (the uncontrollable, potentially

dangerous) to wilderness (the seemingly natural but curated by

man—think of national parks, protected landscapes, etc.). 22 The

Otherness that Cronon attributes to wildness relates directly to the

capital-O Otherness in Jacque Lacan: the provocative, perturbing,

disturbing enigma of the Other as an unknowable (which is differ-

ent from Lacan’s lowercase-o other, used when referring to the

21 The language of “observable and report- other as an alter-ego, imagined as being like oneself).

able” is from Harold Garfinkel, Studies

The questions that Cronon raises about our nostalgia for

in Ethnomethodology (Cambridge: Polity

Press, 1967), 1-2 and is quoted in Paul wilderness are profound. They point us to ask whether the Other

Dourish, Where the Action Is: The Foun- must always bend to our will. If not, under what circumstances

dations of Embodied Interaction (Cam- should it be allowed to flourish without our intervention? The con-

bridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2001), 79. cept of wildness is one that follows its own rules—that evolves in

22 William Cronon, “The Trouble with Wil-

response to many diverse factors also other than human and that

derness: A Response,” Environmental

History 1 (1996), 47–55. cannot be fully understood by humans. Folding the rich art and

50 DesignIssues: Volume 33, Number 4 Autumn 2017

Figure 2 practice of improvisation into the way we look at the design of

Sloth-bots, slow moving autonomous box interactions in today’s hybrid urban environments means allowing

structures that continuously reconfigure space for this Otherness. It means allowing for the unexpected and the

conditioned by people’s behavior, project and unforeseeable, embracing this Other in the way we shape and acti-

photo by i-DAT.org, 2006.

vate our environment.

Design Experimentation with the Unforeseen

Artifacts and environments that display some of these four charac-

teristics of improvisational dynamics already exist. In this section,

I provide three such examples that represent a trajectory toward an

improvisational perspective on the design of urban interactions.

The first example is “Sloth-bots” (see Figure 2), which are

large autonomous and box-like robots that move very slowly, at a

speed that is barely perceptible. By doing so, they reconfigure the

physical architecture over time as a result of their interactions with

people. Sloth-bots pick up on the use of the space they are in and

how it changes throughout the day, and they reposition themselves

in response to and anticipation of new interactions with building

occupants.

With respect to the key positions I propose for an improvi-

sation-based model for interaction; the spatial configurations gen-

erated by the Sloth-bot are characterized by an openness that is

continuously renegotiated between the responsive physical ele-

ment and the human constituents of the space as they condition

and reflect each other’s behavior. The where, when, and how of the

Sloth-bot moves emerges out of the interaction with building resi-

dents and the physical context. The moves involve no plan, as such,

but rather a protocol of constraints that together with people’s

behavior results in the movement being constantly conceived as it

is enacted. The object cannot be controlled and might block pas-

sage, divide space, direct, facilitate flow, or otherwise. These mean-

ings are attributed as they emerge from the interplay between

people and Sloth-bot, rather than being prescribed. The effect of

this ongoing process of regeneration is remarkable because it

results in a continuous novelty, bestowed upon a space that might

otherwise seem familiar.

DesignIssues: Volume 33, Number 4 Autumn 2017 51

Figure 3 The second example is “Fearful Symmetry” by Ruairi Glynn

Fearful Symmetry, an exploration into (see Figure 3), which explores how an object’s expression of pur-

processes of attribution of purpose by poseful behavior can bring it to life in the eye of the observer. The

observers through an autonomous luminous work is part of his investigation into how our sense of the built

object. Project by Ruairi Glynn; photo by

environment as inert and lifeless might change to one that is rich

Simon Kennedy.

in synthetic personalities and strange forms of artificial life as we

are increasingly in the presence of artificially intelligent machines,

contextually aware devices, sensory spaces, and robotic agency.

The project illustrates a number of the key positions I propose.

Unlike the Sloth-bot, timing of actions and cues is at a cadence that

observers can continuously sense as they see the animated light

object, recognizing form in the making. Observers position them-

selves in relation to these anticipated forms, and the object’s

behavior is itself conditioned by these moves, fostering something

akin to a dance and a constant redefinition of one’s own behavior

as part of the process. The object can be considered wild in its

behavior because its modus operandi is not fully understood and it

continuously displays unexpected behavior. However, the object

also offers the possibility of discovering—in the practice of inter-

acting with it—the quality of its responsiveness, and the observer

is offered the possibility of taking the initiative.

The third example is the dynamic shading system “Cloud

Seeding,” installed at the Design Museum Holon in Israel by Modu

(see Figure 4), which turns a shading structure from a static entity,

animated predictably by the sun alone, into a dynamic interplay

between moving shades and people. Wind animates balls on a net

structure, casting shadow patches on a public square in unpredict-

able yet accountable ways. Passersby engage by rearranging public

furniture in response to the behavior of these shades.

52 DesignIssues: Volume 33, Number 4 Autumn 2017

Figure 4 Unlike the two previous projects, Cloud Seeding does not

Cloud Seeding, dynamic shading system monitor people’s behavior but factors in environmental conditions

continuously reconfigured by wind and sun in its behavior. It is an open work in that the shading structure

as people reconfigure around changing

continuously reconfigures and conditions without prescribing

shades below. Project by MODU; photo by

the way people arrange themselves and objects underneath. The

Aviad Bar Ness.

structure’s behavior prompts response, opens possibilities for

action, and is an invitation to make inventive use of this public

space. It cannot be controlled, but it is accountable because the

projected shades are driven by suspended balls, wind, and sun—

all of which are perceivable. In this way, forms can be recognized

at their onset and behavior adapted to anticipate completed con-

figurations. Even if they might eventually manifest differently,

this ongoing process drives an inventive reconfiguration and

appropriation of public space.

Improvisation for the Design of Urban Applications: The Case

of the Viewpoints Technique for Responsive Urban Lighting

The discussion thus far illustrates how the proposed key posi-

tions can be used to analyze existing projects in the context of an

improvisation-based model of interaction. But how can this model

be instrumentalized and inform an experimental design process?

Performers use a rich variety of articulated improvisation

methods and techniques in their training and practice, which I

propose to use to help inform the process of designing respon-

sive systems and environments. Viewpoints is one such technique

that is particularly interesting given the scope of this article (see

Figure 5). It was developed in the 1970s by Mary Overlie, was later

formalized by Anne Bogart and Tina Landau, and is used exten-

sively today.23

23 Anne Bogart, and Tina Landau, The View-

points Book: A Practical Guide to View-

points and Composition (New York:

Theatre Communications Group, 2004).

DesignIssues: Volume 33, Number 4 Autumn 2017 53

Figure 5 In Viewpoints Improvisation, individual and collective

Viewpoints improvisation by Northeastern activity emerges in real time based on actors’ heightened aware-

University theater students in motion capture ness and immediate response to any of nine viewpoints that form

studio. Project by Kristian Kloeckl, Mark Sivak,

the structural basis of the technique and that are temporal or spa-

and Jonathan Carr; photo by Kristian Kloeckl.

tial in nature: Tempo, duration, kinesthetic response, and repetition are

the temporal viewpoints; spatial relationship, topography, shape, ges-

ture, and architecture are the spatial viewpoints.

In improvisational practice, these viewpoints are first intro-

duced one at a time, guiding actors’ awareness, attention, and

action. Then, multiple viewpoints are combined, developing com-

plex dynamics of interaction. A viewpoints coach can facilitate the

process and guide the actors’ awareness to any one or any combi-

nation of viewpoints in their work. Rather than elucidate the view-

points in the context of improvisation performance alone, I want to

illustrate briefly how this technique can be used to support the

design of a concrete urban application—responsive street light-

ing—in relation to the four key positions of our model.

The integration of LED, sensing, and network technologies

is enabling street lighting systems today to dynamically respond

to human presence and activity. In this way, street lights can be

controlled individually based on demand, offering an enticing

opportunity to address urban energy consumption and light pollu-

tion. Although working prototypes of such systems do exist, the

design of the behavior of these light systems is not straightforward

because street lighting touches on manifold issues, such as general

visibility, way-finding, exploration, active use of outdoor spaces,

and safety.24 A common approach for the behavior of these systems

holds to a “light follows people” notion, activating or modulating

street lights as a reaction to locally detected human presence.

24 A recent project in the City of Copenha-

Although feasible, this approach appears limiting, raising ques-

gen offers one example of a prototype.

tions related to the visibility ahead of possible paths, visibility for

See Diane Cardwell, “Copenhagen Light-

ing the Way to Greener, More Efficient exploration, and ad hoc path direction based on available lighting

Cities,” New York Times (December 8, versus presence triggered lighting.

2014), https://www.nytimes.com/2014/ So, let us turn to Viewpoints Improvisation to see how this

12/09/business/energy-environment/

technique can inform the design of responsive urban lighting.

copenhagen-lighting-the-way-to-greener-

more-efficient-cities.html (accessed

January 25, 2017).

54 DesignIssues: Volume 33, Number 4 Autumn 2017

With a focus on the viewpoint repetition, actors experiment

with letting when, how, and for how long they move be determined by

repetition: repeating someone else, someone close, someone far

away, repeating off two people simultaneously. Actors experiment

with repetition over time, recycling movements carried out by oth-

ers in the near or distant past—reproducing forms and figures and

repurposing them for the dialogue in that moment. Experimenting

with repetition in the context of responsive urban lighting offers a

number of directions. The light path, formed by individually con-

trolled light posts, can follow a pedestrian, repeating its path in

real time. However, it also can repeat these paths at later moments,

triggered by other pedestrians, illuminating traces of past activity

and so forming an invitation to explore unexpected paths.

Tempo is concerned with how fast or slow an action is. View-

points improvisation explores extremes of tempo—very fast and

very slow—and guides the attention to meaning created by the

action’s tempo (e.g., slow to touch or fast to grab). In terms of

responsive urban lighting, any light path activates in a certain way,

one lamp at a time, so that a sense of motion and of tempo is con-

veyed.25 This unfolding of a light path can be slow or fast; it can

reflect the rhythm of the walker or contrast with it, leading to

questions of how different tempos of light might feed back and

condition people’s walking itself.

Duration works on an awareness of how long an action lasts,

developing a sense of how long is long enough to make something

happen, or how long is too long so that something starts to die.

Viewpoints improvisation willingly pushes beyond behavioral

comfort zones to make something happen. For urban lighting, this

strategy leads to experimentation to determine how long a light

path should stay lit—whether it dims once a pedestrian leaves the

light cone or whether it stays lit until she or he turns the corner.

Kinesthetic response brings attention to other bodies in

space, to their movements, and it encourages exploration of one’s

own behavior as being affected by external mobility. The focus is

now on when you move instead of how fast or slow and for how

long you move, as an immediate response to an external event.

The bodies in space directly involved, in the context of the light-

ing application, are the people and the lighting structures, and

the development of lighting behavior can be based on the proxim-

ity between these two. The intensity of a light can increase as a

person comes close, reflecting the impact of a passerby. Walking

along a lit path then changes from experiencing an evenly lit space

to one in which one’s own movement translates into rhythmic

waves of light, quite naturally reflecting and anticipating one’s

own way of moving through space—a gentle pulse conditioned by

people’s movements.

25 This apparent movement was defined as

phi phenomenon in 1910 by Max Wert-

heimer, co-founder of Gestalt psychology.

DesignIssues: Volume 33, Number 4 Autumn 2017 55

At this point, the work with four viewpoints has helped

generate a number of dynamic behavioral sketches. (Work with the

other five viewpoints can be done in a similar way, and this work

of course can be developed in greater depth.) Some of these view-

points-based light behaviors might then be combined, increasing

the complexity of the overall system behavior.

The behavior of this improvisational urban light system

is now notably different from its original static or reactive version,

and an examination through the lens of the four positions pre-

sented earlier reveals that difference: Its behavior embodies how

design for initiative ensures openness in that the behavior of the light

system and that of the people are mutually constitutive. Both peo-

ple and the lighting system have agency for taking the first step,

and this provides openings for people to participate in the produc-

tion of urban light. Any change in how people move in space con-

ditions how light is modulated, and this change in light opens

possibilities for a change in people’s behavior and paths. The sys-

tem is open but not arbitrary because the behavior structures

developed through the work with Viewpoints Improvisation

frames the field of possibilities, determining a focus of attention

and an awareness of the system.

In this system awareness of time ensures the relevance of actions

in that the way and tempo at which a person engages with an

emerging light path becomes a constitutive part of the timing of

the interaction between person and lighting system. Timing

becomes paramount, and meaning is attributed to an unpredict-

able lighting behavior by the way a person engages with it in the

here and now. Observing the city at a specific place and lit in a cer-

tain way at any one moment becomes a unique opportunity for an

observer to engage in an exploration possible only at that moment.

If engaged, the light will follow along—in some way; otherwise,

that moment and its light condition will pass.

Forms of action are understood in the making, in that a person

observes and interprets light paths, anticipating an upcoming form

of these paths simultaneously, as they unfold. At the same time, a

person’s path also is picked up and interpreted by the system.

Changes in path direction are interpreted to anticipate a future

path and are used to determine lighting behavior. Cues that point

to upcoming behaviors become critical. For example, the pulsating

light developed through the viewpoint of kinesthetic response

becomes indexical for light paths that are in the process of unfold-

ing, and this pulsating light feeds into the interaction with the

passersby. At times these anticipated behavioral forms correspond

to subsequent actions; at other times, these expectations will not be

fulfilled. Such misunderstandings are welcome and an integral

56 DesignIssues: Volume 33, Number 4 Autumn 2017

part of the improvisational nature of this interaction; they are the

noise that leads to the emergence of novel behavior, both by the

people and by the lighting system.

These interactions themselves are Other than expected because

the behavior of this lighting system is conditioned by people’s

behavior, but its functioning can neither be fully understood nor

controlled. The lighting system never quite repeats the same

behavior, and interactions between people and the lighting system

are unpredictable and do not cease to surprise. The result is an

urban environment whose lighting conditions are in constant flux.

And with the changing light, the city appears to the observing

bystander in ever-changing ways.

What an improvising urban light system does is offer a way

to reduce the energy consumed by urban street lighting compared

to always-on systems. However, it does so without collapsing the

city’s visual presence and availability to the sole location of an

urban observer, as is done by “light follows people” systems. An

improvisation-based modality of interaction, as outlined, enables a

night-time illumination of a city that is akin to the uniqueness and

liveliness of light conditions generated by daylight illumination

and its interplay of reflections, refractions, and shadings. Further-

more, it opens up the possibility for people’s direct participation in

the behavior of an urban environment without falling back into

reactive behavior patterns.

Toward the Urban Improvise

“The worth of cities is determined by the number of places in them

made over to improvisation,” notes Siegfried Kracauer.26 Graeme

Gilloch synthesizes this pledge emphatically in his thesis for a

future city: “for moments, against monuments.”27 This article con-

textualizes, proposes, and experiments with a new model for inter-

actions with and within responsive artifacts and environments in

today’s hybrid cities. Design has so far looked at improvisation for

the enactment of user scenarios and personas to identify opportu-

nities and challenges of design interventions. The art and practice

of improvisation and the emerging field of improvisational stud-

ies, in conjunction with the current and imminent development of

26 From the original German, “Der Wert der connected technologies, instead provides an opportunity to bring

Städte bestimmt sich nach der Zahl der a more foundational perspective of improvisation into the design

Orte, die in ihnen, der Improvisation domain. I have here discussed how a focus on improvisational per-

eingeräumt sind,” in Siegfried Kracauer, formance can expand on earlier and alternative models of interac-

Straßen in Berlin und Anderswo [Streets

tion, described how improvisation is tightly linked to the urban

in Berlin and Elsewhere] (Berlin:

Suhrkamp, 2009), 71.

dimension, and examined how a detailed look at the nature of

27 Graeme Gilloch, “Seen from the Window: improvisation as a system allows us to formulate a number of key

Rhythm, Improvisation and the City,” in positions that point toward an improvisation-based model for

Bauhaus and the City: A Contested Heri-

tage for a Challenging Future, ed. Laura

Colini and Frank Eckardt (Würzburg: Koe-

nigshausen & Neumann, 2011), 201.

DesignIssues: Volume 33, Number 4 Autumn 2017 57

interaction. An analysis of three existing projects illustrates how

elements of an improvisation-based perspective on interaction are

already being used in the field and how they relate to key posi-

tions of an improvisation-based model. Finally, this article illus-

trates, through the specific application of responsive urban

lighting, how improvisation techniques can be used to directly

guide the design of responsive urban environments. Design, in

this perspective, moves the behavior and the performance of

things center stage, taking inspiration from non-scripted forms of

interaction and embracing the unforeseen and unexpected as con-

structive aspects of its production.

58 DesignIssues: Volume 33, Number 4 Autumn 2017

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- 41370602Document3 pages41370602Omega ZeroNo ratings yet

- Typography: Formation and Transformation by Willi Kunz: Jan ConradiDocument2 pagesTypography: Formation and Transformation by Willi Kunz: Jan ConradiOmega ZeroNo ratings yet

- Azure-Planning and Finding Solutions For Migration - MOPDocument7 pagesAzure-Planning and Finding Solutions For Migration - MOPVijay RajendiranNo ratings yet

- Electronic Modular Control Panel II - para Motores EUIDocument168 pagesElectronic Modular Control Panel II - para Motores EUIRobert Orosco B.No ratings yet

- Backlog Including Delta Requirements and Gaps: PurposeDocument30 pagesBacklog Including Delta Requirements and Gaps: PurposeCleberton AntunesNo ratings yet

- FRY, Tony - Design - FuturingDocument45 pagesFRY, Tony - Design - FuturingOmega Zero100% (1)

- Successful Activism Strategies: Five New Extensions To AshbyDocument11 pagesSuccessful Activism Strategies: Five New Extensions To AshbyOmega ZeroNo ratings yet

- Design For A Common World: On Ethical Agency and Cognitive Justice Maja Van Der VeldenDocument11 pagesDesign For A Common World: On Ethical Agency and Cognitive Justice Maja Van Der VeldenOmega ZeroNo ratings yet

- Design Without Final Goals - Getting Around Our Bounded Rationality Jude Chua Soo MengDocument7 pagesDesign Without Final Goals - Getting Around Our Bounded Rationality Jude Chua Soo MengOmega ZeroNo ratings yet

- YACAVONE Daniel - Film and The Phenomenology of ArtDocument28 pagesYACAVONE Daniel - Film and The Phenomenology of ArtOmega ZeroNo ratings yet

- Steps To An Ecology of Knowing and To Te PDFDocument18 pagesSteps To An Ecology of Knowing and To Te PDFOmega ZeroNo ratings yet

- Narrative Structure in Comics Making Sen PDFDocument3 pagesNarrative Structure in Comics Making Sen PDFOmega ZeroNo ratings yet

- Calendar - Week - 29:07:18 To 04:08:18Document1 pageCalendar - Week - 29:07:18 To 04:08:18Omega ZeroNo ratings yet

- Reading Between The Panels A Review of Barbara Pos PDFDocument3 pagesReading Between The Panels A Review of Barbara Pos PDFOmega ZeroNo ratings yet

- (REVIEW) KENDALL, Stuart - The Philosophy of Design by Glenn ParsonsDocument5 pages(REVIEW) KENDALL, Stuart - The Philosophy of Design by Glenn ParsonsOmega ZeroNo ratings yet

- The Routledge Companion To Design Studies: Penny Sparke, Fiona FischerDocument12 pagesThe Routledge Companion To Design Studies: Penny Sparke, Fiona FischerOmega ZeroNo ratings yet

- The Politics of Design Conversations: Review of Victor Margolin's Politics of The ArtificialDocument6 pagesThe Politics of Design Conversations: Review of Victor Margolin's Politics of The ArtificialOmega ZeroNo ratings yet

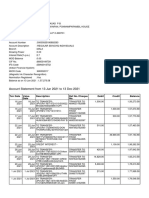

- Account Statement From 13 Jun 2021 To 13 Dec 2021Document10 pagesAccount Statement From 13 Jun 2021 To 13 Dec 2021Syamprasad P BNo ratings yet

- SAC Training 01Document11 pagesSAC Training 01Harshal RathodNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Noise Measurement TerminologyDocument24 pagesA Guide To Noise Measurement TerminologyChhoan NhunNo ratings yet

- ADAMS Summary User GuideDocument58 pagesADAMS Summary User GuideGalliano CantarelliNo ratings yet

- P2P Technology User's ManualDocument8 pagesP2P Technology User's ManualElenilto Oliveira de AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- Block Diagram and Signal Flow GraphDocument15 pagesBlock Diagram and Signal Flow GraphAngelus Vincent GuilalasNo ratings yet

- ADPRO XO5.3.12 Security GuideDocument19 pagesADPRO XO5.3.12 Security Guidemichael.f.lamieNo ratings yet

- Appendix B: Technical InformationDocument11 pagesAppendix B: Technical InformationOnTa OnTa60% (5)

- Harshitha C P ResumeDocument3 pagesHarshitha C P ResumeHarshitha C PNo ratings yet

- Advanced Computer Architectures: 17CS72 (As Per CBCS Scheme)Document31 pagesAdvanced Computer Architectures: 17CS72 (As Per CBCS Scheme)Aasim InamdarNo ratings yet

- Temario Spring MicroserviciosDocument5 pagesTemario Spring MicroserviciosgcarreongNo ratings yet

- ATtribute Changer 7Document19 pagesATtribute Changer 7manu63_No ratings yet

- Practical-8: Write A Mobile Application That Creates Alarm ClockDocument7 pagesPractical-8: Write A Mobile Application That Creates Alarm Clockjhyter54rdNo ratings yet

- 29 TAC ExamplesDocument8 pages29 TAC ExamplessathiyanitNo ratings yet

- Verilog File HandleDocument4 pagesVerilog File HandleBhaskar BabuNo ratings yet

- CV-Sushil GuptaDocument3 pagesCV-Sushil Guptaanurag_bahety6067No ratings yet

- CIS201 Chapter 1 Test Review: Indicate Whether The Statement Is True or FalseDocument5 pagesCIS201 Chapter 1 Test Review: Indicate Whether The Statement Is True or FalseBrian GeneralNo ratings yet

- Agenda: - What's A Microcontroller?Document38 pagesAgenda: - What's A Microcontroller?Hoang Dung SonNo ratings yet

- AFF660 Flyer April 2015Document2 pagesAFF660 Flyer April 2015Iulian BucurNo ratings yet

- Theories and Principles of Public Administration-Module-IVDocument12 pagesTheories and Principles of Public Administration-Module-IVAnagha AnuNo ratings yet

- TopFlite Components - Tinel - Lock® RingDocument1 pageTopFlite Components - Tinel - Lock® Ringbruce774No ratings yet

- FINALEXAM-IN-MIL Doc BakDocument4 pagesFINALEXAM-IN-MIL Doc BakObaidie M. Alawi100% (1)

- 1B30 07Document542 pages1B30 07saNo ratings yet

- HP48 RepairsDocument7 pagesHP48 Repairsflgrhn100% (1)

- Listening and Speaking 3 Q: Skills For Success Unit 3 Student Book Answer KeyDocument4 pagesListening and Speaking 3 Q: Skills For Success Unit 3 Student Book Answer KeyFahd AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Lisa08 BrochureDocument36 pagesLisa08 BrochuremillajovavichNo ratings yet

- Control Systems Control Systems Masons Gain Formula-Www-Tutorialspoint-ComDocument6 pagesControl Systems Control Systems Masons Gain Formula-Www-Tutorialspoint-ComshrikrisNo ratings yet