Professional Documents

Culture Documents

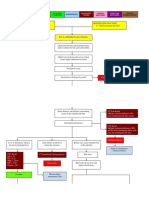

Jaundice

Uploaded by

Abigail LonoganCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jaundice

Uploaded by

Abigail LonoganCopyright:

Available Formats

INTRODUCTION

Obstructive jaundice is caused by a blockage of the bile ducts, which prevents the bile from

flowing out of the liver. Obstructive jaundice can also occur if the bile ducts are missing or have been

destroyed. As a result, bile cannot pass out of the liver, and bilirubin is forced back into the blood.

The manifesting features and clinical signs and symptoms of obstructive jaundice are: yellow

discoloration of the skin and the mucous membranes; stools are pasty and whitish; urine becomes dark

yellow-brown; nausea; vomiting; pruritus or itching of the skin; fever; pain in the abdomen; loss of

appetite; fatigue; confusion; headache.

Obstructive jaundice frequently requires a surgical cure. If the original passageways cannot be

restored, surgeons have several ways to create alternate routes. A popular technique is to sew an open

piece of intestine over a bare patch of liver. Tiny bile ducts in that part of the liver will begin to

discharge their bile into the intestine, and pressure from the obstructed ducts elsewhere will find release

in that direction. As the flow increases, the ducts grow to accommodate it. Soon all the bile is

redirected through the open pathways.

Approximately 10 to 15 percent of the people with gallstones have them in the common bile

duct. More elderly people have gallstones in the common bile duct, for it is estimated that 25 percent of

them have stones in this duct. Most gallstones are formed within the gallbladder, but many leave the

gallbladder and migrate to the common bile duct. From there, the stones may continue on to the small

intestines or stay in the common bile duct and obstruct the bile flow.

ANATOMY and PHYSIOLOGY

The gallbladder is a pear shaped organ located on the liver that stores bile. It is connected to the

intestinal system by the cystic duct which in turn empties into the common bile duct. When we eat a

large or fatty meal, nerve and chemical signals cause our gallbladder to contract thereby adding bile

into our digestive system.

The different layers of the gallbladder are as follows:

The epithelium, a thin sheet of cells closest to the inside of the gallbladder

The lamina propria, a thin layer of loose connective tissue (the epithelium plus the lamina

propria form the mucosa)

The muscularis, a layer of smooth muscular tissue that helps the gallbladder contract, squirting

its bile into the bile duct

The perimuscular ("around the muscle") fibrous tissue, another layer of connective tissue

The serosa, the outer covering of the gallbladder that comes from the peritoneum, which is the

lining of the abdominal cavity

The gall bladder stores the bile that is made in your liver. The purpose of bile, a greenish yellow

watery substance, is to break down the fat in your food into smaller pieces that eventually get absorbed.

After a meal, the gall bladder is stimulated by hormones in your gut to empty the bile into your

intestine. The bile drains out of the gallbladder into the intestine via the cystic duct. Bile can also drain

directly from the liver into the hepatic ducts. The hepatic ducts join the cystic duct to form the common

bile duct. Thus, all bile ultimately makes its way to the intestine via the common bile duct. Bile is made

up of 80% cholesterol and 20% bile salts. The bile salts act to dissolve the cholesterol and maintain bile

in liquid form.

Gallstones are solid stones that are formed in your gall bladder. Gallstones are formed either by

excess cholesterol in your body or a low amount of these dissolving bile salts. Gallstone disease is

usually manifested as pain after you eat, typically when you have eaten a fatty meal. As bile is being

emptied out of your gall bladder to digest the fat, the stone can begin to flow out with the bile but not

make it past the cystic duct, temporarily blocking it and causing pain. That pain is usually on the right

side where your gall bladder lies, but occasionally the pain can be in the middle of your belly

underneath your rib cage or to the left. The pain typically lasts 30 minutes to 2 hours and is often

accompanied by nausea and vomiting. The pain is severe enough to limit your activities. Shorter,

isolated episodes of gallstone attacks are called “biliary colic.” The pain of biliary colic is relieved

when the stone eventually pops back into the gallbladder or gets passed through the duct. If the stone

does not pass, then the gallbladder can become very inflamed. If the pain lasts greater than 4 hours,

then gallbladder inflammation is occurring. This is it is called acute cholecystitis and will generally not

get better unless the gall bladder is removed.

The adult human gallbladder stores about 50 millilitres (1.7 U.S. fl oz; 1.8 imp fl oz) of bile, which

is released into the duodenum when food containing fat enters the digestive tract, stimulating

the secretion of cholecystokinin (CCK). The bile, produced in the liver, emulsifies fats in partly

digested food.

During storage in the gallbladder, bile becomes more concentrated which increases its potency and

intensifies its effect on fats.

Gallstones can cause other conditions such as pancreatitis, cholangitis, and small bowel

obstruction if they migrate beyond the cystic duct.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Maximizing Growth Factors for Height IncreaseDocument29 pagesMaximizing Growth Factors for Height IncreaseMegaV100% (2)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Pathophysiology - Obstructive JaundiceDocument3 pagesPathophysiology - Obstructive JaundiceAbigail Lonogan0% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Concept Map - F and EDocument1 pageConcept Map - F and EAbigail LonoganNo ratings yet

- Prioritizing Nursing Problems for a Patient with PneumoniaDocument1 pagePrioritizing Nursing Problems for a Patient with PneumoniaAbigail Lonogan100% (2)

- HeparinDocument2 pagesHeparinNinoska Garcia-Ortiz100% (4)

- One Page NCPDocument2 pagesOne Page NCPAbigail LonoganNo ratings yet

- Name: Age: Gender: Civil Status: Religion: Birthday: Birth Place: Nationality: Address: Occupation: Phic: Case: Date & Time Admitted: Chief Complaint: History of Present IllnessDocument2 pagesName: Age: Gender: Civil Status: Religion: Birthday: Birth Place: Nationality: Address: Occupation: Phic: Case: Date & Time Admitted: Chief Complaint: History of Present IllnessAbigail LonoganNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia JournalDocument4 pagesSchizophrenia JournalAbigail LonoganNo ratings yet

- Celecoxib uses, dosage, side effectsDocument4 pagesCelecoxib uses, dosage, side effectsAbigail LonoganNo ratings yet

- Predisposing Factors Facilitating Factors: PsychopathologyDocument2 pagesPredisposing Factors Facilitating Factors: PsychopathologyAbigail LonoganNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Palliative Nursing CareDocument3 pagesIntroduction to Palliative Nursing CareAbigail LonoganNo ratings yet

- For Drug Recitation 1Document33 pagesFor Drug Recitation 1Abigail LonoganNo ratings yet

- Surname Nickname Payment Size ChartDocument2 pagesSurname Nickname Payment Size ChartAbigail LonoganNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Palliative Nursing CareDocument3 pagesIntroduction to Palliative Nursing CareAbigail LonoganNo ratings yet

- Spaulding Classification of InstrumentsDocument1 pageSpaulding Classification of InstrumentsAbigail Lonogan100% (1)

- Aromatherapy During LaborDocument12 pagesAromatherapy During LaborAbigail LonoganNo ratings yet

- DOH Herbal PlantsDocument16 pagesDOH Herbal Plantskyra_naomiNo ratings yet

- HIV Journal - PhilippinesDocument1 pageHIV Journal - PhilippinesAbigail LonoganNo ratings yet

- Types of AnesthesiaDocument2 pagesTypes of AnesthesiaAbigail LonoganNo ratings yet

- TRAIN LawDocument1 pageTRAIN LawAbigail LonoganNo ratings yet

- Type of CastsDocument1 pageType of CastsAbigail LonoganNo ratings yet

- Chemotherapy Benefit PackageDocument2 pagesChemotherapy Benefit PackageAbigail LonoganNo ratings yet

- Mini Cog ToolDocument2 pagesMini Cog ToolSegun Dele-davidsNo ratings yet

- Quantitative and Qualitative ResearchDocument7 pagesQuantitative and Qualitative ResearchAbigail LonoganNo ratings yet

- Surgery Options, Risks & Benefits ExplainedDocument4 pagesSurgery Options, Risks & Benefits ExplainedAbigail LonoganNo ratings yet

- 1743 7075 8 75 PDFDocument16 pages1743 7075 8 75 PDFPutri Wulan SukmawatiNo ratings yet

- Sigmund Freud: Psychoanalytic TheoryDocument18 pagesSigmund Freud: Psychoanalytic TheoryAbigail LonoganNo ratings yet

- Mini Cog ToolDocument2 pagesMini Cog ToolSegun Dele-davidsNo ratings yet

- Careers in Nursing: Click Arrows To Move Ahead & BackDocument27 pagesCareers in Nursing: Click Arrows To Move Ahead & BackAbigail LonoganNo ratings yet

- Therapeutic Communication Techniques - NursingDocument3 pagesTherapeutic Communication Techniques - NursingAbigail Lonogan100% (1)

- Macbook Air Users GuideDocument76 pagesMacbook Air Users GuideEric Li CheungtasticNo ratings yet

- Levels of Academic Stress Among Senior High School Scholar Students of The Mabini AcademyDocument18 pagesLevels of Academic Stress Among Senior High School Scholar Students of The Mabini AcademyRaymond Lomerio100% (1)

- Kotlyar 2016Document1 pageKotlyar 2016dasdsaNo ratings yet

- LAB EXERCISE 1 Organization of The Human BodyDocument8 pagesLAB EXERCISE 1 Organization of The Human Bodyley leynNo ratings yet

- Fuel Metabolism in StarvationDocument27 pagesFuel Metabolism in Starvationilluminel100% (2)

- M 371Document14 pagesM 371Anonymous h0DxuJTNo ratings yet

- Journal Reading Radiologi EllaDocument44 pagesJournal Reading Radiologi EllaElla Putri SaptariNo ratings yet

- 2018 Biology Exercises For SPM (Chapter6 & Chapter7)Document15 pages2018 Biology Exercises For SPM (Chapter6 & Chapter7)Kuen Jian LinNo ratings yet

- Science (Digestion) Notes/ActivityDocument4 pagesScience (Digestion) Notes/ActivityHi HelloNo ratings yet

- Abbreviation For ChartingDocument12 pagesAbbreviation For ChartingJomar De BelenNo ratings yet

- Lecture 8 - 30.12.2022Document17 pagesLecture 8 - 30.12.2022Adnan Mohammad Adnan HailatNo ratings yet

- Body WeightDocument23 pagesBody WeightIkbal NurNo ratings yet

- Biochem QbankDocument16 pagesBiochem Qbank786waqar786No ratings yet

- The Science of Laughing - Worksheet 3Document3 pagesThe Science of Laughing - Worksheet 3Maria Alexandra PoloNo ratings yet

- Vit CDocument10 pagesVit C3/2 no.34 สรัญญากร สีหาราชNo ratings yet

- Tetanus Neonatorum LectureDocument11 pagesTetanus Neonatorum LectureJackNo ratings yet

- SP FinalDocument18 pagesSP Finalapi-344954734No ratings yet

- Pharmacology Nursing ReviewDocument19 pagesPharmacology Nursing Reviewp_dawg50% (2)

- Shah Et Al-2016-Frontiers in Plant ScienceDocument28 pagesShah Et Al-2016-Frontiers in Plant ScienceJamie SamuelNo ratings yet

- Biology Mcqs Part IDocument17 pagesBiology Mcqs Part IUsama NiaziNo ratings yet

- Risk For Decreased Cardiac OutputDocument4 pagesRisk For Decreased Cardiac Outputapi-283482759No ratings yet

- Metabolism of DisaccharidesDocument15 pagesMetabolism of DisaccharidesminaNo ratings yet

- Anxiety: What Are Some Symptoms of Anxiety?Document3 pagesAnxiety: What Are Some Symptoms of Anxiety?Khairil AshrafNo ratings yet

- Standardized Tools for Assessing Traumatic Brain InjuryDocument5 pagesStandardized Tools for Assessing Traumatic Brain InjuryGenera Rose Radaza Villa100% (3)

- Muscles of Mastication Functions and Clinical SignificanceDocument130 pagesMuscles of Mastication Functions and Clinical SignificanceDevanand GuptaNo ratings yet

- Auxin Controls Seed Dormacy in Arabidopsis (Liu, Et Al.)Document6 pagesAuxin Controls Seed Dormacy in Arabidopsis (Liu, Et Al.)Jet Lee OlimberioNo ratings yet

- AP PSYCHOLOGY EXAM REVIEW SHEETDocument6 pagesAP PSYCHOLOGY EXAM REVIEW SHEETNathan HudsonNo ratings yet

- Ujian Sumatif 1 Biologi 2023Document12 pagesUjian Sumatif 1 Biologi 2023Siti Nor AishahNo ratings yet

- Assignment Lec 4Document3 pagesAssignment Lec 4morriganNo ratings yet