Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Culture and The Good Teacher in The EL Classroom (Sowden, 2007)

Uploaded by

Arivalagan NadarajanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Culture and The Good Teacher in The EL Classroom (Sowden, 2007)

Uploaded by

Arivalagan NadarajanCopyright:

Available Formats

Culture and the ‘good teacher’ in the

English Language classroom

Colin Sowden

Downloaded from http://eltj.oxfordjournals.org at Kyungpook National uinversity on April 25, 2010

In the present post-method situation, E LT has become increasingly sensitive to

the issue of culture. However, this concept has been defined so broadly that it

cannot fill the gap left by the retreat from methodology. In the absence of objective

guidelines about what to do in the classroom, the teacher has returned to

centre stage, but as a more informed, articulate, and empowered professional.

Introduction Many readers must sympathize with Peter Grundy (1999) when he laments

the fact that after 30 years in the E LT profession, he still does not know

how to do his job. It seems indeed that, despite all the discussion, research,

and experimentation which has taken place over that time, it has not yet

been demonstrated that there is a best way of teaching a second language.

This conclusion has been a common theme in recent writings: although

different new methods have appeared to offer an initial advantage over

previous or current ones, none has finally achieved overwhelmingly better

results. Even the Communicative Approach, which has done so much to

restructure how we as language teachers view our activities, has had its

detractors and has not proven more obviously successful than other

methods in the past. There has indeed been methodological fatigue, leading

many to the pragmatic conclusion that informed eclecticism offers the best

approach for the future.

While confidence in specific methods has declined, interest in individual

learner differences, such as motivation, aptitude, family background, has

noticeably increased. If we cannot say exactly how we should teach, then

perhaps we must let our learners determine how they should learn, and

be guided by that instead. Thus has developed an interest in learner training

and self-directed learning, and in what is termed the student-centred

approach, either in its strong form, whereby the teacher and learners

negotiate the syllabus, or in its weak form, whereby the teacher tries to

ensure that what happens in the classroom responds to learners’ needs

and interests as well as to external or traditional requirements. It is in

conjunction with this shift of emphasis away from teaching and towards

learning, that there has appeared a growing awareness of the role played by

culture in the classroom.

A broad definition of In the past, culture tended to mean that body of social, artistic, and

culture intellectual traditions associated historically with a particular social, ethnic

304 E LT Journal Volume 61/4 October 2007; doi:10.1093/elt/ccm049

ª The Author 2007. Published by Oxford University Press; all rights reserved.

or national group. One could talk confidently of French culture, the culture

of the Marsh Arabs, or British working-class culture. Now this term is used

much more broadly. In his analysis of the expatriate teaching situation,

Holliday (1994:29) argues that the typical teacher in that context will be

involved in a variety of cultures: those of the nation, of the specific academic

discipline, of international education, of the host institution, of the

classroom, and of the students themselves. To be effective, expatriate

teachers must take account of all these cultures and how they influence the

attitude and study styles of their students. Instead of trying to impose

cultures of their own, they must work with the cultures that they encounter.

Downloaded from http://eltj.oxfordjournals.org at Kyungpook National uinversity on April 25, 2010

Reflecting on what determined the approach of local teachers whom he

observed during his time in Egypt, he comments (ibid.: 38)

the relationship between teacher and student seemed not so much

a product of explicit methodology; it was rather derived more naturally

from existing, unspoken role expectations, perhaps originating outside

the classroom.

Holliday presents guidelines for ways in which expatriate teachers can learn

from this observation by becoming better informed about local cultures and

adapting their teaching styles accordingly (ibid.: 193).

Diversity of culture, though, as Holiday’s analysis indicates, is not confined

to the expatriate situation. Even when teachers of English share the

nationality of their students, it is misleading to talk of cultural homogeneity.

Although they are likely to share many of the cultural assumptions of

their students, local teachers, who are not usually native speakers of English,

may well be seen to represent certain values that set them apart. In

implementing a national curriculum or experimenting with imported new

teaching methods, for instance, such teachers may also find a significant

gulf between themselves and their classes. Canagarajah (1999) explores this

kind of situation at considerable length, analysing the way in which Tamil

teachers of English in Sri Lanka need to take account in their work of the

cultures associated with government policy, particular ethnic aspirations,

the colonial heritage of the language, and student lifestyles and objectives.

The cultures of Of course, teachers need to be aware not only of the cultures of their students

teachers and their environment, but also of the cultures that they themselves bring

to the classroom, whether they are nationals or expatriates. This is not

just a question of the historical and social baggage that, for example, an

American or a metropolitan from New Delhi, inevitably carries with them,

but of the particular attitudes and practices that they have developed as

individuals. Woods (1996: 196) refers to a teacher’s ‘B AK’: their underlying

beliefs, assumptions, and knowledge. These determine how what is

planned is implemented in practice. He says of course design and delivery:

‘When a [plan] is carried out, it is interpreted using familiar structures in

a way which is coherent with the teacher’s BAK. By virtue of this

interpretation, the actual curriculum—what happens to the learners in the

classroom—is different from the planned curriculum’(ibid.: 269).

Even when we are dealing with culture in the more traditional sense, this

is increasingly seen primarily as a context within which personal identity

Culture and the ‘good teacher’ 305

can be worked out. Kramsch is very clear that learning another language

necessarily involves learning about the cultures with which it is associated.

She says (1993: 8): ‘If language is seen as a social practice, culture becomes

the very core of language teaching’. However, this does not mean that the

learner should merely take on board wholesale all that these other cultures

offer or represent. Instead there should exist a ‘border zone’ between the

target language cultures and local cultures (represented by both teacher

and learners or by learners alone), which all parties can meaningfully

inhabit and within which everyone can interact on equal terms. Effective

language learning will take place in this way, whatever the formal

requirements of the syllabus, when teachers and learners ‘are constantly

Downloaded from http://eltj.oxfordjournals.org at Kyungpook National uinversity on April 25, 2010

engaged in creating a culture of a third kind through the give-and-take of

classroom dialogue’ (ibid.: 23). In similar vein, Canagarajah (op. cit.: 176)

argues that students and national teachers of English in ‘periphery’

countries should negotiate a new identity for themselves through the

language, stamping their own identity on it and modifying it in accordance

with their own needs and priorities.

The scope of These different perspectives on the role of culture in the classroom

inter-cultural demonstrate how very broadly the term has come to be employed in the

communication teaching context. It approximates in meaning to the patterns of behaviour

training and the belief systems which teachers and learners have evolved in response

to both their general social context and their particular life experience.

Broadly speaking, this could be paraphrased as ‘how people live or aspire to

live in their world’. Understanding this, it seems, is more important than

knowing how to teach in any narrow, mechanical sense of that idea.

Certainly the writers whose works I have quoted seem clearly to be

indicating that concern for culture must predominate over concern for

method, irrespective of what any official teaching syllabus might declare.

Naturally, this imperative places a huge burden on the shoulders of the

teacher, who must cope with the multi-faceted challenge that it presents.

In order to meet this challenge, courses have been developed to improve the

inter-cultural communicative competence of both teachers and students.

The understanding of culture here is usually the more limited and

traditional one, pertaining to the life-style and values of a given people

and society, with linguistic and/or pedagogical implications following on

from these. Through a series of exercises, such courses aim to sensitize

participants to the cultural issues involved in operating in a trans-cultural

situation, and to equip them to meet the related challenges that they will

face there. This process ‘involves an implicit and sometimes explicit

questioning of the learner’s assumptions and values; and explicit

questioning can lead to a critical stance, to ‘‘critical cultural awareness’’’

(Byram and Fleming 1998: 6).

A good example here is Utley’s Intercultural Resource Pack (Utley 2004).

This is a well-designed book which aims, in a convincing way, to promote

cultural awareness and encourage self-reflection. However, in parts

(primarily between pages 19 and 49), it does require users to provide

overviews of their own and other cultures. This is no easy matter: there is

no guarantee that they will be able to identify or explain relevant features

of these cultures. In addition, there is no provision for checking or

306 Colin Sowden

correcting any opinions which are offered, which could well reinforce rather

than challenge existing prejudices. This is Guest’s point (2002: 154) when

he warns of the dangers inherent in trying to generalize superficially about

other cultures:

much E F L cultural research has had the unfortunate result of

misrepresenting foreign cultures by reinforcing stereotypes and

constructing these cultures as monolithic, static ‘Others’, rather

than as dynamic fluid entities.

This distorts our understanding of them and achieves exactly the opposite

result from that intended.

Downloaded from http://eltj.oxfordjournals.org at Kyungpook National uinversity on April 25, 2010

In fact, to develop familiarity with another culture, to improve one’s real

inter-cultural skills, it is necessary to live within that culture for a good

period of time, to be what Byram (1997: 1) terms a ‘sojourner’ rather than

a tourist. You need to experience the culture from inside as ‘an active

participant in a community’ (Barro et al. 1998: 83). As Barro (ibid.) says,

‘culture is not something prone, waiting to be discovered but an active

meaning-making system of experiences which enters into and is

constructed within every act of communication’. Barro and her colleagues

were writing with reference to the year abroad organized as part of the

Modern Languages Degree course at Thames Valley University. In the

context of a formal, structured setting, it is only through ethnography of

the kind required on this programme that real insights and skills can be

developed, but it is a time-consuming process which is impractical for

most people to undertake. In most cases, therefore, it is doubtful how

one can talk meaningfully about developing inter-cultural communicative

competence outside of the context in which it will actually be required.

Byram (ibid.: 33) identifies four main components of inter-cultural

communicative competence: knowledge, attitude, skills of interpretation

and comparison, and skills of discovery and interaction. While he admits

that these ‘can in principle be acquired through experience and reflection,

without the intervention of teachers and educational institutions’, he is

nonetheless keen to promote their being taught in the classroom setting.

Yet both attitude and knowledge, and to a large extent the other skills

mentioned, are essentially attributes that people bring to the situation rather

than abilities which can be produced there in a short time. In other words,

they reflect who a person is, in terms of background, education, personality

and experience, rather than what they can be trained to do in terms of

discrete skills. This is true for both national and expatriate teachers.

Although, as noted above, the cultural issues in question will differ in many

respects, the personal qualities that professionals need in order to be able to

navigate effectively around them are very much the same: ‘curiosity and

openness, readiness to suspend disbelief about other cultures and beliefs

about one’s own’ (Byram ibid.: 50).

The profile of a Appropriate personal qualities, therefore, are what count most in the

‘good teacher’ development of good intercultural communicative competence. In fact,

I would argue, they are the key to overall success in the classroom, and

this has not really changed over the years, although concern with the

latest technique and method has tended to obscure this fact. As Brumfit

Culture and the ‘good teacher’ 307

(2001: 115) says ‘the ability to relate to learners, the role of enthusiasm for the

subject and the interaction of these with a sense of purpose and organization

were as relevant in 1500 as in 2000’.

Now, in the absence of clear methodological guidelines, and with an

understanding of culture too broad to be of real pedagogical assistance,

the teacher as person is coming to be recognized as the determining factor

in the teaching process, just as the learner as person has been recognized

as the key to successful learning. This ‘good teacher’, a well-rounded,

confident and experienced individual, will be at ease in their classroom role:

their teaching will be effective because it will be a natural product of who

Downloaded from http://eltj.oxfordjournals.org at Kyungpook National uinversity on April 25, 2010

they are, and be received as such by their students.

This is what Prabhu (1990: 172) refers to as ‘a teacher’s sense of plausibility

about teaching’. He goes on to say (ibid.: 173) ‘The question to ask about

a teacher’s sense of plausibility is not whether it implies a good or bad

method but, more basically, whether it is active, alive, or operational enough

to create a sense of involvement for both the teacher and the student’. It

is the exercise of these qualities which matters and gets results. In a similar

affirmation of authenticity, Brumfit comments (1982: 16) on the ideals

of Humanistic Language Teaching, by saying that ‘. . . successful affective

teaching is more likely to emerge when students join a community in

which they are provided with an example of the desired behaviour pattern

than when the patterns are built into some kind of syllabus structure’. In

other words, success as a teacher does not depend on the approach or

method that you follow so much as on your integrity as a person and the

relationships that you are able to develop in the classroom. The ability

to build and maintain human relationships in this way is central to

effective teaching, as it is to true inter-cultural communicative competence

(Byram (op. cit.: 32).

The role of teacher Recognition of this fact has led to the traditional idea of teacher training

development giving way to the more far-reaching concept of teacher development. If

what I do in class depends mainly on who I am as a person, then I must

develop myself as much as I can if I wish to improve as a teacher. As far

as development in the classroom is concerned, teachers need to enhance

those reflective and critical skills which will allow them to assess and

appropriately modify their performance in the light of experience and of

the insights provided by research, both their own and that of experts in the

field. This process is described well by Tsui (2003: 277):

the theorization of practical knowledge and the ‘practicalization’ of

theoretical knowledge are two sides of the same coin in the development

of expert knowledge . . . and they are both crucial to the development of

expertise.

Such reflection helps prevent that ‘overroutinization’ which Prabhu (op. cit.:

174) considers to be the pre-eminent ‘enemy of good teaching’. It also helps

the teacher develop an individual voice, one which does not merely echo

external criteria and concerns, but gives expression to the teacher’s own

inner dynamic.

308 Colin Sowden

Of course, the fact that the teacher is all-important means that reflection

on our classroom activity must involve reflecting on ourselves. Such

self-analysis can be hard, even painful, because it may point towards

changes which threaten our security and self-image. This is why many

practitioners, even those apparently committed to the idea of professional

development, avoid it, though perhaps unwittingly. They may be impressed

by a new idea, but not actually allow it to modify how they behave. As Myers

and Clark (2002: 51) comment:

Our own concerns centre round our own experience that CPD

[Continuous Professional Development] does not always produce related

Downloaded from http://eltj.oxfordjournals.org at Kyungpook National uinversity on April 25, 2010

change in the workplace . . . our own thinking is that most people have

an assimilative. . . .mind-set to CPD—i.e. they see it in terms of accruing

knowledge and skills rather than anticipating a deeper, accommodative

sort of change that could lead to real change in their subsequent

behaviour.

It is in order to overcome this barrier that self-exploration needs to be

a central element of teacher development programmes, helping

participants to progressively unpeel the various personal and cultural layers

that they have accumulated.

The teacher in charge If authenticity is the key factor in the classroom and, in a sense, we teach

who we are, then teacher development really becomes a matter of self-

development. If this is so, then, arguably, learning a musical instrument,

having a child, or achieving a greater level of fitness, may be as relevant to

your work as improving your technique at teaching grammar and

vocabulary if the end result is to make you a more fulfilled, more confident,

more interesting practitioner. Certainly such personal growth will help

us deal more easily with inter-cultural challenge: the more we understand

the world, human relations, and ourselves, the better able we will be to

empathize with others and make connections.

This merging of private and professional selves to achieve an integrated

identity with which we can feel satisfied, is a challenging but necessary

project. However, while this prospect may be invigorating for an

experienced practitioner, it can seem daunting to a novice, who is usually

looking for simple signposts to follow. To be told that teachers must rely

primarily on their own experience and expertise in order to chart their

way ahead, can be alarming. Yet expertise is not an abstract system of rules

which can be absorbed and then enacted; it is a personal construct which

is built up over a lifetime. As such, it involves a dynamic relationship with

the overlapping cultures and schemata within which the teaching takes

place. Tsui (op. cit.: 64) comments:

Teacher knowledge . . . should be understood in terms of the way

[teachers] respond to their contexts of work, which shapes the way their

knowledge is developed. This includes their interaction with the people

in their contexts of work, where they constantly construct and reconstruct

their understanding of their work as teachers.

Since teachers’ lives are different one from another, so their expertise will

differ, with no model emerging as an obvious template. What is right is

Culture and the ‘good teacher’ 309

what works in a given context in terms of all the various cultures which

operate there, including those represented by the teacher.

So how can we respond to Peter Grundy’s lament mentioned at the

beginning of this article? If we accept that our profession is an art rather

than a science, and if we recognize that our personal qualities, attitudes, and

experience are what finally count, providing that these are informed by

acquaintance with best current practice and research, then we language

teachers can free ourselves from the kind of mechanistic expectations that

have dogged us for so long. If we can accept this argument, we become

genuinely free agents, able to decide for ourselves not only how best to carry

Downloaded from http://eltj.oxfordjournals.org at Kyungpook National uinversity on April 25, 2010

out our jobs but also how to direct our future professional development.

How do we know that we are doing a good job? Student response and

progress, which must be carefully evaluated, will provide the principal

guidance here. Peter must have had lots of positive feedback from

students during his career, and seen good concrete results from his

teaching. With apologies to Keats: ‘That is all you know in English language

teaching, and all you need to know’.

Final revised version received June 2005

References Kramsch, C. 1993. Context and Culture in Language

Barro, A., S. Jordan, and C. Roberts. 1998. ‘Cultural Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

practice in everyday life: the language learner as Myers, M. and S. Clark. 2002. ‘C PD, lifelong

ethnographer’ in M. Bryam and M. Fleming (eds.). learning and going meta’ in J. Edge (ed.). Continuing

Language Learning in Intercultural Perspective. Professional Development. Whitstable: I AT E F L.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Prabhu, N. S. 1990. ‘There is no best method—

Brumfit, C. 1982. ‘Some doubts about Humanistic why? T E S O L Quarterly 24/2: 161–76.

Language Teaching’ in P. Early. Humanistic Tsui, A. B. M. 2003. Understanding Expertise in

Approaches: an Empirical View. London: The British Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Council. Utley, D. 2004. Intercultural Resource Pack.

Brumfit, C. 2001. Individual Freedom in Language Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Woods, D. 1996. Teacher Cognition in Language

Byram, M. 1997. Teaching and Assessing Intercultural Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge

Communicative Competence. Clevedon: Multilingual University Press.

Matters.

Byram, M. and M. Fleming. (eds.). 1998. Language The author

Learning in Intercultural Perspective. Cambridge: Colin Sowden is Director of the International

Cambridge University Press. Foundation Course at the University of Wales

Canagarajah, A. S. 1999. Resisting Linguistic Institute, Cardiff. He has taught general English,

Imperialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. E SP, and E AP in Italy, the United Kingdom, and the

Grundy, P. 1999. ‘From model to muddle’. English United Arab Emirates. He is interested in the role of

Language Teaching Journal 53/1: 54–5. individual differences among learners of English

Guest, M. 2002. ‘A critical ‘‘checkbook’’ for culture and in intercultural communication.

teaching and learning’. E LT Journal 56/2: 154–61. Email: C A Sowden@uwic.ac.uk

Holliday, A. 1994. Appropriate Methodology and Social

Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

310 Colin Sowden

You might also like

- Sowden, C - Culture and The Good TeacherDocument7 pagesSowden, C - Culture and The Good Teacherhellojobpagoda100% (3)

- i01-2CC83d01 - Intercultural Communication in English Language Teacher EducationDocument9 pagesi01-2CC83d01 - Intercultural Communication in English Language Teacher EducationMuhammad Iwan MunandarNo ratings yet

- A Flexible Framework For Task-Based Lear PDFDocument11 pagesA Flexible Framework For Task-Based Lear PDFSusan Thompson100% (1)

- Incorporating Dogme ELT in The Classroom: Presentation SlidesDocument17 pagesIncorporating Dogme ELT in The Classroom: Presentation Slideswhistleblower100% (1)

- Course Syllabus Production Checklist (Items To Consider)Document2 pagesCourse Syllabus Production Checklist (Items To Consider)api-26203650No ratings yet

- Dogme Language Teaching - WikipediaDocument3 pagesDogme Language Teaching - WikipediaAmjadNo ratings yet

- Incorporating Culture Into Listening Comprehension Through Presentation of MoviesDocument11 pagesIncorporating Culture Into Listening Comprehension Through Presentation of MoviesPaksiJatiPetroleumNo ratings yet

- Handbook Language Course Teaching Methods For SenDocument49 pagesHandbook Language Course Teaching Methods For SensagagossardNo ratings yet

- Assessing SpeakingDocument4 pagesAssessing SpeakingLightman_2004No ratings yet

- Designing Authenticity into Language Learning MaterialsFrom EverandDesigning Authenticity into Language Learning MaterialsFrieda MishanNo ratings yet

- From Cultural Awareness To Intercultural Awarenees Culture in ELTDocument9 pagesFrom Cultural Awareness To Intercultural Awarenees Culture in ELTGerson OcaranzaNo ratings yet

- UI Learner ProfilesDocument3 pagesUI Learner ProfilesEmily JamesNo ratings yet

- TESOL Quarterly (Autumn 1991)Document195 pagesTESOL Quarterly (Autumn 1991)dghufferNo ratings yet

- Concept of TeacherDocument3 pagesConcept of TeacherHilmi AzzahNo ratings yet

- Grammar BackgroundDocument10 pagesGrammar Backgroundpandreop100% (1)

- Prompting Interaction in ELTDocument24 pagesPrompting Interaction in ELTwhistleblowerNo ratings yet

- Task-based grammar teaching of English: Where cognitive grammar and task-based language teaching meetFrom EverandTask-based grammar teaching of English: Where cognitive grammar and task-based language teaching meetRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- Thomas Imoudu GOMMENT Obi Success ESOMCHIDocument13 pagesThomas Imoudu GOMMENT Obi Success ESOMCHIhussainiNo ratings yet

- Error Correction PDFDocument41 pagesError Correction PDForlandohs11No ratings yet

- Teaching Literacies in Diverse ContextsFrom EverandTeaching Literacies in Diverse ContextsSinéad HarmeyNo ratings yet

- Post Method PedagogyDocument11 pagesPost Method PedagogyTaraprasad PaudyalNo ratings yet

- Framework of TBLTDocument9 pagesFramework of TBLTJulianus100% (1)

- Coursebooks: Is There More Than Meets The Eye?Document9 pagesCoursebooks: Is There More Than Meets The Eye?Alessandra Belletti Figueira MullingNo ratings yet

- SA102 10 AL-Madany Delta3 MON 0615Document39 pagesSA102 10 AL-Madany Delta3 MON 0615Raghdah AL-MadanyNo ratings yet

- Grammar in Context by Nunan PDFDocument9 pagesGrammar in Context by Nunan PDFjuliaayscoughNo ratings yet

- ELLIS (2008) - The Dynamics of Second Language Emergence - Cycles of Language Use, Language Change, and Language AcquistionDocument18 pagesELLIS (2008) - The Dynamics of Second Language Emergence - Cycles of Language Use, Language Change, and Language AcquistionSayoNara CostaNo ratings yet

- Innovation in English Language Teacher Education Edited by George Pickering and Professor Paul GunashekarDocument290 pagesInnovation in English Language Teacher Education Edited by George Pickering and Professor Paul GunashekarmariahkalNo ratings yet

- Speaking TBL 1 PDFDocument3 pagesSpeaking TBL 1 PDFEko Wahyu ApriliantoNo ratings yet

- 1 Lesson Seen30063Document6 pages1 Lesson Seen30063Roselyn Nuñez-SuarezNo ratings yet

- Using L1 in Esl Class by SchweersDocument5 pagesUsing L1 in Esl Class by SchweersRidzwan Rulam Ahmad100% (1)

- Teaching Grammar and Young LearnersDocument46 pagesTeaching Grammar and Young Learnersapi-262786958No ratings yet

- Seedhouse ArticleDocument7 pagesSeedhouse ArticleDragica Zdraveska100% (1)

- Perspectives English As A Lingua Franca and Its Implications For English Language TeachingDocument18 pagesPerspectives English As A Lingua Franca and Its Implications For English Language Teachingcarmen arizaNo ratings yet

- Conversation Strategies and Communicative CompetenceFrom EverandConversation Strategies and Communicative CompetenceRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Averil Coxhead - Pat Byrd - 2007Document19 pagesAveril Coxhead - Pat Byrd - 2007mjoferNo ratings yet

- David NunanDocument10 pagesDavid NunanDany GuerreroNo ratings yet

- How Languages Are Learned Lightbown and Spada Chapter 3Document18 pagesHow Languages Are Learned Lightbown and Spada Chapter 3nancyNo ratings yet

- Pronunciation Teaching Approaches: Considering The Options: TESOL Atlanta March 13, 2019Document25 pagesPronunciation Teaching Approaches: Considering The Options: TESOL Atlanta March 13, 2019Miss Kellys Vega100% (2)

- Language and EFL Teacher Preparation in Non-English-Speaking Environments PeretzDocument33 pagesLanguage and EFL Teacher Preparation in Non-English-Speaking Environments PeretzNataly LeónNo ratings yet

- Sakui & Cowie 2012 The Dark Side of Motivation Teachers' Perspectives On UnmotivationDocument9 pagesSakui & Cowie 2012 The Dark Side of Motivation Teachers' Perspectives On UnmotivationhoorieNo ratings yet

- Ticv9n1 011Document4 pagesTicv9n1 011Shafa Tiara Agusty100% (1)

- Teaching Mathematics in English To Vietnamese 6th GradeDocument5 pagesTeaching Mathematics in English To Vietnamese 6th Gradeha nguyen100% (1)

- Are Is Alves Process Writing LTMDocument24 pagesAre Is Alves Process Writing LTMM Nata DiwangsaNo ratings yet

- Dogme 3 +++Document23 pagesDogme 3 +++daguiani mohamedNo ratings yet

- EP Background EssayDocument5 pagesEP Background Essayjdiazg09103803No ratings yet

- The Process Approach To Writing PDFDocument4 pagesThe Process Approach To Writing PDFracard1529100% (1)

- AFFECT IN L2 LEARNING AND TEACHING Jane ArnoldDocument7 pagesAFFECT IN L2 LEARNING AND TEACHING Jane ArnoldMartina Slankamenac100% (2)

- Memohon Khidmat Bantu ICT Untuk SK XXXDocument1 pageMemohon Khidmat Bantu ICT Untuk SK XXXArivalagan NadarajanNo ratings yet

- Basic Spoken English E-BrochureDocument1 pageBasic Spoken English E-BrochureShahnawazSoomroNo ratings yet

- Basic Spoken English E-BrochureDocument1 pageBasic Spoken English E-BrochureShahnawazSoomroNo ratings yet

- Answers BiDocument1 pageAnswers BiArivalagan NadarajanNo ratings yet

- Resignation LetterDocument1 pageResignation LetterArivalagan NadarajanNo ratings yet

- Application LetterDocument1 pageApplication LetterArivalagan NadarajanNo ratings yet

- English Teacher Guidebook Year 2Document330 pagesEnglish Teacher Guidebook Year 2Azlan Ahmad100% (2)

- Classroom Management Critical EssayDocument6 pagesClassroom Management Critical EssayArivalagan NadarajanNo ratings yet

- Integrated Curriculum Project On ThankfulnessDocument4 pagesIntegrated Curriculum Project On Thankfulnessapi-316364007No ratings yet

- Sample Teacher Workshop: Active Learning: Day OneDocument5 pagesSample Teacher Workshop: Active Learning: Day OneAlRSuicoNo ratings yet

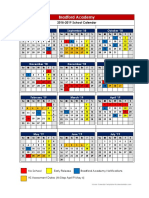

- Bradford 2018-2019 School CalendarDocument2 pagesBradford 2018-2019 School Calendarapi-445613297No ratings yet

- Creative Activity and Lesson PlanningDocument2 pagesCreative Activity and Lesson Planningrom keroNo ratings yet

- II. Ecoliteracy and The Different ApproachesDocument34 pagesII. Ecoliteracy and The Different Approachesgerrie anne untoNo ratings yet

- Ma. Fe D. Opina Ed.DDocument3 pagesMa. Fe D. Opina Ed.DNerissa BumaltaoNo ratings yet

- Mme Reflection PaperDocument10 pagesMme Reflection Paperapi-622190193No ratings yet

- CISA Demo ClassDocument13 pagesCISA Demo ClassVirat AryaNo ratings yet

- Advanced Machine Learning Challenge2Document22 pagesAdvanced Machine Learning Challenge2RANJIT BISWAL (Ranjit)No ratings yet

- Gen. Chem. Week 5-6Document2 pagesGen. Chem. Week 5-6MARIBETH RAMOSNo ratings yet

- Magic Milk PDFDocument5 pagesMagic Milk PDFapi-459217235No ratings yet

- Math Ice CreamDocument2 pagesMath Ice Creamapi-532687773No ratings yet

- Learning Task 3 Isc PDFDocument9 pagesLearning Task 3 Isc PDFMariel Jane MagalonaNo ratings yet

- 25 Myths About HomeworkDocument10 pages25 Myths About Homeworkcfd13b82100% (1)

- Research Chapter 1 3Document16 pagesResearch Chapter 1 3Aila Micaela KohNo ratings yet

- Tool For Learners Comprehensive Profiling - Personal Assessment - and - EvaluationDocument5 pagesTool For Learners Comprehensive Profiling - Personal Assessment - and - EvaluationCharlota PelNo ratings yet

- Recent Trends of HRD in IndiaDocument3 pagesRecent Trends of HRD in Indiadollygupta100% (5)

- Result of Delhi University Entrance Test (DUET) - 2020 University of DelhiDocument288 pagesResult of Delhi University Entrance Test (DUET) - 2020 University of DelhiJATIN YADAVNo ratings yet

- Pre-Service Teachers Competency and Behavior in Teaching Ibong Adarna: Input For Instructional ProgramDocument24 pagesPre-Service Teachers Competency and Behavior in Teaching Ibong Adarna: Input For Instructional ProgramMa. Angelie FontamillasNo ratings yet

- A SWOT Analysis of E-Learning Model For The Libyan Educational InstitutionsDocument7 pagesA SWOT Analysis of E-Learning Model For The Libyan Educational Institutionshu libyanNo ratings yet

- Critical Thinking - Writing ArgumentDocument4 pagesCritical Thinking - Writing ArgumentIndra FardhaniNo ratings yet

- Teaching From A Disciplinary Literacy StanceDocument6 pagesTeaching From A Disciplinary Literacy StancesherrymiNo ratings yet

- BSBINS603 - Assessment Task 2Document18 pagesBSBINS603 - Assessment Task 2Skylar Stella83% (6)

- Immersion PortfolioDocument16 pagesImmersion PortfolioJazen AquinoNo ratings yet

- Assessment, Record-Keeping and Evaluating Progress in The Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS)Document8 pagesAssessment, Record-Keeping and Evaluating Progress in The Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS)Nada JamusNo ratings yet

- Behaviorist PerspectiveDocument27 pagesBehaviorist PerspectiveKhiem AmbidNo ratings yet

- Field Study 1: Observations of Teaching-Learning in Actual School EnvironmentDocument12 pagesField Study 1: Observations of Teaching-Learning in Actual School EnvironmentAndrea MendozaNo ratings yet

- Suggestopedia Method of TeachingDocument5 pagesSuggestopedia Method of Teachingerica galitNo ratings yet

- Daily Lesson LOG: School: Grade Level: Teacher: Learning Areas: Teaching Week QuarterDocument3 pagesDaily Lesson LOG: School: Grade Level: Teacher: Learning Areas: Teaching Week QuarterKennedy Fieldad VagayNo ratings yet

- Application Letter ApprenticeshipDocument2 pagesApplication Letter ApprenticeshipPrasad VaradaNo ratings yet