Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Advertising

Uploaded by

Hajnalka RemeteCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Advertising

Uploaded by

Hajnalka RemeteCopyright:

Available Formats

Speakers The Ancient History of Advertising:

Boh Insights and Implications for Practitioners

What Today’s Advertisers and Marketers

Can Learn from Their Predecessors

FRED K. BEARD

University of Oklahoma Editor's Note:

fbeard@ou.edu "Speaker's Box" invites academics and practitioners to identify potential areas o f research affecting mar

keting and advertising. Its intention is to bridge the gap betioeen the length of time it takes to produce

rigorous work and the acceleration o f change within practice. With this contribution, Fred Beard takes a

step backfrom an industry that seems to reinvent itself daily with new platforms, new media, and new data

sources. From this distance, he reviews some ideas, practices, and events that contributed to the history c f

advertising and advertising thought before the 19th century. In doing so, he proposes ways that body of

thought might be relevant to present-day practice. He notes, to his dismay, how prevalent and influential

the belief is that nothing remotely resembling "modern" advertising existed before it was "invented" by

the 20th-century American pioneers. Beard argues that, in fact, advertising has a rich, relevant history.

Here, he exposes the bias against historic relevance and suggests some o f its consequences.

Douglas C. West

Professor of Marketing, King's College London

Visiting Fellow of Kellogg College, University of Oxford

Contributing Editor, Journal o f Advertising Research

INTRODUCTION how the past has helped shape the present? Can a

Many historians date the dawn of modern adver deeper understanding of and appreciation for the

tising and branding to the beginning of the 20th ancient history of advertising and branding, the lat

century, and they tend to fixate on the philosophies ter of which advertising historians have claimed as

and practices of the period's American pioneers, part of their subject matter, inform the beliefs and

such as Albert Lasker, Claude Hopkins, George practices of its 21st-century practitioners in any

Rowell, Francis Wayland Ayer, Harley Procter, meaningful, or even interesting, ways?

James L. Kraft, and J. Walter Thompson. Any ear As the authors of a textbook on promotions

lier history, they contend, largely is irrelevant when management observed, "studying a subject with

it comes to gaining a deeper understanding of the out an appreciation of its antecedents is like seeing

institution and business of advertising, as well as a picture in two dimensions—there is no depth.

what its theory and practice can teach about con The study of history gives us this depth as well as

sumption, culture, creativity, economics, and the an understanding of why things are as they are"

media. (Brink and Kelley, 1963, p. 4).

These biases might have produced the combined The early Mesopotamians, Chinese, Greeks, and

view that anything occurring before the late 19th Romans all appreciated the value of a good promo

or early 20th centuries—or the contributions of tion. Witness the following:

anyone other than the founding American adver

tising fathers—is unimportant. Do other biases in • Iron Age Greek potters used trademarks and

advertising's historiography limit the ability to see mottos to differentiate their brands.

DOI: 10.2501/JAR-2017-033 September 2017 JOUROflL OF RDUERTISIAG RESEARCH 239

THE ANCIENT HISTORY OF ADVERTISING: INSIGHTS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTITIONERS

• Medieval Chinese manufacturers relied

on consumer word of mouth (WOM) to

promote their offerings.

• Point-of-purchase advertisem ents and

political campaign posters are visible on

the walls of Pompeii and Herculaneum.

• In w hat m ight have been considered

(very) early consumer packaged-goods

branding, "garum " (a fermented fish

sauce) was marketed under several brand

names throughout the Roman Empire.

• In late 15th-century London, printer Wil

liam Caxton used the United Kingdom's %$ •?. **

first printing press to produce the first

book. His second use of the new equip

ment was to produce an advertisement

to f “

(called a "tackup" in his day) to sell the

book. Source: Chinese History Museum, ed., Zhongguo godai shi cankao tulu: Song Yuan

shiqi (Shangha : Shanghai Education Publishing House, 1991). Retrieved from:

h ttp s://d epts.w 3 shin gtor.ed U /chin aciv/g rap h/9co m m a in .h tm # bu nny.

Critical of contentions that advertis

ing m ight have "flourished" centuries

ago, journalism professor Vincent Norris Figure 1 Branding for the White Rabbit Brand Sewing Needles

(1980, p. 4) argued that those responsible

(Song Dynasty, 9 6 0 -1 2 7 9 AD)

had neglected to mention that "advertis

ing is associated with market activity and

even more so w ith market economies, and 20th-century advertisers of soap and pat The earliest of these premodern or pro

that until very recently there was very lit ent medicines strategically began to craft tobrands existed in the Bronze Age in

tle of the former and none of the latter." messages in support of their wares. Indus Valley, China, M esopotamia, and

The critique raises an interesting question. Such advertising w as inform ed by elsewhere in the ancient world (Moore and

Are popular views of advertising's his relentless repetition, psychological brand Reid, 2008). Historians have proposed that

tory, in fact, severely limited by w hat his ing principles, and the power of the mass premodern brands functioned in some of

torian Stefan Schwarzkopf (2011) called the media. H istorical research in the early the same ways brands did in the early 20th

"m odernization" and "Americanization" 2000s, however, began to challenge the century. They were used to control and

philosophical paradigms? view that "m odern'’ brands are vastly dif ensure quality and to inform prospective

ferent from their ancient counterparts in consumers about the origin and authentic

BRANDING AND ADVERTISING term s of their characteristics, functions, ity of goods chat were produced in quan

ACROSS THE CENTURIES and contributions to consumer cultures. tity and exported to distant markets.

Until recently, m any historians tracked At its simplest, branding involves the Modern brand theory and management

the ancient origins of brands and brand use of a tangible m ark or symbol that also recognize the role of brands as convey

ing back to the burning of a mark on cat differentiates a product or service from ors of image, status, power, and personal

tle and m anufactured goods. They then those of competitors. Brands and brand ity. Early brands have been found to have

quickly moved on to developments during ing, in fact, are related to an ancient his possessed these qualities as well. For exam

the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In tory of product-container seals as well as ple, some 7th-century BC Greek potters

such cases, modernization and Americani commodity marks and labels, all of which inscribed their work with mottos intended

zation paradigm atic lim itations encour were in common use 2,000 to 3,000 years to portray an image to prospective buyers

aged the assum ptions that "true" brands ago (Eckhardt and Bengtsson, 2010; Moore (Moore and Reid, 2008). In what may be his

did not exist until prim arily American and Reid, 2008; Wengrcw, 2008). tory's first instance of a direct comparison

240 JOURnHL OF A D U E R T IS in O RESERRCH Septem ber 2017

THE a NC ENT HISTORY OF ADVERTISING: INSIGH“ S AND IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTITIONERS THEARF.ORG

15th to the late 18th century), some his

torical evidence shows that organic WOM

was im portant during the Chinese Ming

Dynasty (Eckhardt and Bengtsson, 2010).

Lacking from the literature are other histo

ries of the importance of either organic or

actively encouraged WOM. Some 500 years

later, the importance of WOM remains sub

stantially unchallenged, with the Word of

Mouth Marketing Association proposing it

is the "most effective form of advertising."1

The authors at BuzzTalk made an explicit

connection betw een ancient WOM and

electronic WOM when they observed that

WOM is "the oldest type of marketing we

know."2

The Chinese invented paper during the

Han Dynasty (206 BC to 220 AD), and what

followed were the first advertisem ents

containing words and pictures (Eckhardt

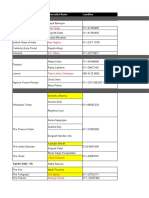

Figure 2 Victorian-Era Advertising Trade Card and Bengtsson, 2010). Movable-type print

ing arrived 500 years sooner in China than

in a oromotional message, Greek potter starting point, a global history of ancient it did in Europe, and popular prom o

Euthymides boasted that a vase he made brands and branding has produced a more tional items, including banners, lanterns,

was of "high quality as never [were those sophisticated understanding of and appre pictures, and printed product w rappers

of] Euphronios," another important poder ciation for the varied processes by which (McDonough and Egoff, 2000), came with

of the same period (Osborne, as cited in brands can evolve and the roles they long the technological advancement.

Mooie and Reid, 2008, p. 428). have played in consumer culture. Printed advertising began in Europe

O ther research on prem odern brands during the mid-15th century, with Guten

in China, w here a consumerist-focused A n c ie n t A d v e rtis in g berg's improved system of movable type.

material culture existed several hund-ed The term "advertisement" first was used in The streets of London soon were littered

years earlier :han in Europe, shows tnat 1655, when it took the place of "advices," with printed tack-ups and handbills. Every

during the Ming Dynasty (1368 to 1644 which previously had supplanted the term available lam ppost and wall—including

AD), consumers themselves took p a r' in "siquis." This term came from ancient those of taverns, town halls, cathedrals, and

the creation of brands via organic WOM Rome, where announcements often began even people's houses—was covered with

(Eckhardt and Bengtsson, 2010). More with the Latin words "Si quis...," meaning them. (It appears that advertising "clutter"

im portant is the fact that some manufac "if anybody..." or "if an y o n e .(F re d e rick , is at least a 500-year-old problem.) One of

turers strategically used visual and veibal 1925; Presbrey, 1929). One key difference the most important media in advertising's

branding elements to portray more com between m odern and ancient advertising history arrived in 1622—the trade or shop

plex image and personality characteristics. is the absence of advertising-supported card (Berg and Clifford, 2007; See Figure 2).

One of these—the White Rabbit branc of media, although below-the-line prom o These were printed in various sizes on good

sewing needles, which originated during tions and media popular in the 17th century

the Song Dynasty (960 to 1279 AD) and remain vital tools of communication today. 1 Word o f Mouth Marketing Association. (2017). "About

W O M M A ." Retrieved from womma.org/about-womma/.

was chosen for its symbolic and mytholog Of the advertising in place during the 2 Kremers, B. (2017). "Electronic word o f mouth presents

ical features (See Figure 1)—is believed to earliest periods—before and during clas a window o f opportunity for businesses." Retrieved from

the BuzzTalk website: www.buzztalkmonitor.com/blog/

be the oldest complete brand in the world sical antiquity, the Middle Ages, and then

bid/233669/Electronic-W ord-O f-M outh-presents-a-win-

(Eckhardt and Bengtsson, 2010). With that the early m odern era (roughly the late dow-of-opportunity-for-businesses.

S e p te m b e r 2 0 1 7 JOUffllAL DF HDUEflTISIHG RESEARCH 241

THE ANCIENT HISTORY OF ADVERTISING: INSIGHTS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTITIONERS

quality paper and distributed to customers advertising, in the form of playbills. These negotiated rates, and gave advice on

as a reminder of their shopping experience playbills were so highly valued, upper- advertising problems (Nevett, 1977). Vol-

and to inform them about newly available crust theater patrons sent their servants ney Palmer, by contrast, would not estab

goods. Expensive, visually sophisticated, out to collect them (Stern, 2006). At the lish America's first agency in Philadelphia

and often persuasive in intent, these were beginning of the 19th century in Brit for another 30 years.

used widely and collected in many coun ain, nationally advertised products and

tries for the next 300 years. brands included condiments, patent med Im p lic a tio n s a n d In s ig h ts fo r Today

The first newspapers appeared in the icines, carbonated water, biscuits, shoe In his study of the prophetic but widely

17th century, and many in Europe as well blacking, and a large variety of health and overlooked writings about advertising

as the American colonies primarily existed beauty aids (Corley, 1988). by mid-19th-century German economist

to carry advertising. The "free shopper" A history of advertising in the Roman Karl Knies, historian Ronald Fullerton

was invented in England in 1692 (Russell, Empire, written as a master's thesis by a observed, "Participants in other business-

1910). In another example of an Americani copywriter at DDB/Needham Worldwide oriented disciplines—accounting, econom

zation, Benjamin Franklin was declared the in Detroit, proposed that the first advertis ics, and management, for example—have

first newspaper entrepreneur to recognize ing professionals might have been Roman come to recognize that they have long and

advertising as his most important source of "signatores" or "scriptores" (scribes or rich intellectual heritages, and that the

revenue (Foster, 1967). A more likely can sign painters; Rokicki, 1987). They solic work they produce today does not emerge

didate, however, is John Houghton, the ited and serviced clients, created advertis in isolation but rather develops out of

"father of English advertising" (Sampson, ing, and arranged for its placement. The and contributes to a long stream of work.

1874). He was the first to conduct a system "album," a flat, whitewashed space on a We in advertising also have a rich herit

atic campaign to promote advertising in a wall, was their primary medium. Adver age, and exploring it can enrich our self

newspaper, beginning in 1692 (Hotchkiss, tising contractors might have controlled understanding" (Fullerton, 1988, p. 64).

1938), although advertisements for his own some of these Pompeiian albums, given The contention, however, persists that

businesses and products soon displaced that they included a variety of announce early nonperiodical media and mes

those of his clients (Walker, 1973). Frank ments (theatrical performances, baths, sages were not really "advertising" and

lin did not launch his Pennsylvania Gazette gladiatorial contests, and circuses), and that any pre-20th-century advertising did

until 1729. locations apparently were chosen for their not contribute much to current practice

Houghton's encouragement of adver high volume of traffic (Presbrey, 1929). (Norris, 1980). These claims appear to be

tising for foods, clothing, luxury items, Both newspapers and advertising agen directly attributable to the modernization

and store goods in general earned him cies can trace their origins to the European and Americanization biases. It is true that

advertising-historian Frank Presbrey's public registries. Inspired by French essay early 20th-century advertising agents and

(1929) nom ination in The History and ist Michel de Montaigne, buyers and sell newspaper publishers struggled to con

Development of Advertising as "the out ers registered their offers and requests, vince businessmen that advertising was

standing advertising figure of the 17th and copies were then distributed to branch both valuable and reputable. A newspaper

Century" (p. 59). offices. Parisian Theophraste Renaudot advertisement for advertising agent R. H.

Toward the end of the Elizabethan (publisher of France's first newspaper, La Fitch, for example, includes a variation of

era (1558 to 1601), English booksellers Gazette) and Englishmen Henry Walker and NW Ayer & Son's widely repeated and fre

unleashed a "flood of advertisements" Marchmont Nedham all established such quently plagiarized slogan "Keeping Ever

(Voss, 1998, p. 737) and further devel "offices of entry" between 1630 and 1657 lastingly at It Brings Success" (See Figure 3).

oped the "advertising arts" by employing (Presbrey, 1929). Ancient branding and advertising, how

sophisticated consumer-focused strategies The first advertising agent likely was ever, often were consistent with modern

and tactics, such as an emphasis on the England's William Tayler, in 1786 (Nevett, strategies and tactics in form, technique,

"new," ornamental type, headlines, wood- 1977). Although most agents at the time and intent. Both clearly were important

cut illustrations, rhyming copy, and market just sold space in one or more newspapers, to many types of manufacturers and mer

segmentation. at least one, Charles Barker, was function chants, and they consistently came into use

The theaters of London during the ing as a true advertising agent as early as with increases in competition. Once the

same period also relied on extensive 1812. He booked insertions in newspapers, earliest production of commodities and

242 JO U R IE OF RDUERTISIRG RESERRCH Septem ber 2017

THE ANCIENT HISTORY OF ADVERTISING: INSIGHTS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTITIONERS THEARF.ORG

However, based on the findings of their

Keeping Everlastingly research on early Chinese brands like the

at It White Rabbit, Eckhardt and Bentsson (2010,

Is th e only w a y to p. 219) argued that "brands are an outcome

MAKE ADVERTISING PAY. rather than the mechanism that generates

T h e tro u b le is. t h a t th e a v e r a g e

rmslnoss m a n h a s too m a n y Irons in consumer culture. That is, consumer culture

tho firo to a tt e n d to th e freque nt

c h an g e oT his a d v e r t is i n g apace pro p develops because of social needs and ten

erly. W h y not

sions and brands emerge to provide status

LET FITC H DO IT and stratification." Indeed, as was noted in

T h o se who h a v e trie d his service

say it is t h e host i n v e s tm e n t for th e a recent edition of the Journal of Advertising

money expended t h a t they h a v e e v e r

made. And t h e c o n tr a c t expire s every

Research Speaker's Box, "armed w ith an

Saturday. abundance of information and opportuni

R . H. FITCH ties, consumers no longer accept the role of

ADVERTISING S P EC IA LIS T. passive recipients of marketing communi

Gazette B’ld’g.. Room 10. 'P h o n e , 330.

NORWALK, CONN. cation" (Acar and Puntoni, 2016, p. 4). It is

A ccurato Mailing Lints cf all s u r r o u n d

ing to wns. C ircu la rs w r i t te n and possible that many never really did, or at

addressed. Advice Free.

least that advertising's cultural influence

Source: The Norwalk Hour, 1910, March 26, p. 5. Retrieved from https://news.googIe. hardly has been uniform around the world

com/newspapers?nid=KKiikWAUrRgC&dat=19100326&printsec=frontpage&hl=en. or across the centuries. By avoiding the

Americanization and modernization biases,

advertising and branding historians might

Figure 3 Advertisement for Advertising Agent R. H. Fitch, 1910 discover other instances in which early

advertisers were able to engage with and

other goods surpassed local consumption of the earliest advertised products to those empower consumers, as previous research

and export to distant markets became via of today also suggests that advertising long ers advocated (Acar and Puntoni, 2016).

ble, it also became necessary to seal, mark, has served a fundamental need for informa Finally, it is important to recognize that

and brand the goods. By 1750, advertising tion, especially about newly available goods "ad bashing" long has been a popular

had become essential to the marketing of that appeal to changing tastes, fashions, and sport. A 16th-century critic of playbills

many British goods and services, with up consumer choices. complained that "by sticking of their bils

to 75 percent of the space in some new spa In addition to the limitations of Ameri in London, [the posters] defile the streetes

pers devoted to it (Walker, 1973). canization and m odernization, another w ith their infectious filthiness" (Stern,

The full pre-20th-century history of im portant bias in advertising's historiog 2006, p. 74). hi 1759, British essayist Samuel

branding and advertising also challenges raphy exists: Much historical work has Johnson wrote, "Advertisements are now

the contention that such tools of brand rec approached the history of advertising and so numerous that they are very negligently

ognition were unim portant to consumers. branding as forms of m anipulation (Berg perused, and it is, therefore, become nec

Historians have confirmed that assurances and Clifford, 2007; Church, 1999). Consum essary to gain attention by magnificence

of purity, quality, authenticity, and brand ers were assumed to be passive recipients of promises, and by eloquence sometimes

consumption as a symbol of status have of a "fictional" world of advertising, where sublim e and som etim es pathetick" (as

been important to commodity consumers "h id d en p ersu ad ers" (Packard, 1957) cited in Rivers, 1929, p. 58). Some 300 years

for thousands of years. Indeed, "the long or "captains of consciousness" (Ewen, later, marketing historian Richard Pollay

history of consumer culture and branding in 1976) were capable of exploiting them. (1977) highlighted the seriousness of the

China demonstrates that the marketplace is Brands also have been viewed as weapons potential consequences for today's adver

not just now becoming a consumer society "wielded by capitalists to extract rents out tisers with the following warning: "Unless

driven by symbolic brand consumption, as of consumers" (Eckhardt and Bengtsson, the history of advertising is exhaustively

is so often argued in both the popular press 2010, p. 218) and have been targeted by researched and accurately docum ented,

and in the academic literature" (Eckhardt contem porary critics such as Kalle Lasn, the industry and those within it stand too

and Bengtsson, 2010, p. 217). The similarity cofounder of Adbusters. great a chance of being demeaned" (p. 3).

September 2017 JOURRRL DFRDUERTISIflGRESEARCH 243

THE ANCIENT HISTORY OF ADVERTISING: INSIGHTS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTITIONERS

C hurch, R. "Advertising Consumer Goods in Po lla y , R. "The Importance, and the Problems,

In The Story of Advertising, magazine

Nineteenth-Century Britain: Reinterpretations." of Writing the History of Advertising." journal of

editor, author, and advertising historian

Economic History Review 53,4 (1999): 621-645. Advertising History 1,1 (1977): 1-5.

James Playsted Wood (1958) offered an

elegant rationale in favor of understanding C o r le y , T. A. B. "Competition and the Growth of P resbrey , F. The History and Development of

and appreciating the connections between Advertising in the U.S. and Britain, 1800-1914."

Advertising. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1929.

ancient advertising and its practice today: Business and Economic History 17 (1988): 155-167.

"Over the centuries, advertising has expe

R ivers , H. W. Ancient Advertising and Publicity.

rienced changes in the proportioning of its E c k h a r d t , G. M., and A. B eng tsso n . "A Brief His

Chicago: Krochs, 1929.

ingredients, in direction, in application, tory of Branding in China." journal of Macromar

but something of the first advertisement keting 30,3(2010): 210-221.

R o k ic k i , ]. "Advertising in the Roman Empire."

survives in the latest, and there will be

Whole Earth Review Spring (1987): 84-87.

Ew en, S. Captains of Consciousness. New York:

traces of it in the last" (p. 502). CID

McGraw-Hill, 1976.

R ussell , T. H. Advertising Methods and Mediums.

F oster , G. A. Advertising: Ancient Marketplace to Chicago: Whitman, 1910.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Television. New York: Criterion Books, 1967.

F red K. B eard is professor o f advertising in the Gaylord Sa m p s o n , H. A History of Advertising from the

College o f Journalism and Mass Communication at the F r e d e r ic k , J. G. "Introduction: The Story of Earliest Times. London: Chatto & Windus, 1874.

University of Oklahoma. Prior to his academic career, Advertising Writing." In Masters of Advertis

he worked as a small-business manager, newspaper ing Copy, J. G. Frederick, ed. New York: Frank- Sc h w a r z k o p f , S. "The Subsiding Sizzle of Adver

advertising-sales representative, and market-research Maurice, 1925. tising History: Methodological and Theoretical

analyst. His work can be found in the Journal of Challenges in the Post Advertising Age." jour

F u lle r t o n , R. A. "A Prophet of Modem Advertis

Advertising, the Journal of Advertising Research, nal of Historical Research in Marketing 3, 4 (2011):

ing: Germany's Karl Knies." journal of Advertising

the Journal of Business Ethics, the Journal of Business 528-548.

Research, the Journal of Macromarketing, the Journal

27,1 (1998): 51-66.

of Historical Research in Marketing, Journalism and St e r n , T. '"On Each Wall and Comer Post': Play

H o t c h k is s , G. B. Milestones of Marketing. New

Communication Monographs. Journalism. History, and bills, Title-Pages, and Advertising in Early Mod

York: MacMillan, 1938.

the Journal of Marketing Communications, among other ern London." English Literary Renaissance 36, 1

publications. M cD o no ug h, J., and K. Eg o ff. The Advertising (2006): 57-89.

Age Encyclopedia of Advertising. Chicago: Fitzroy

Dearborn, 2000. Voss, P. J. "Books for Sale: A dvertising and

REFERENCES Patronage in Late Elizabethan England." Six

M o o re, K., and S. R e id . "The Birth of the Brand:

teenth Century journal 29, 3 (1998): 733-756.

4000 Years of Branding." Business History 50, 4

A car, O. A ., a n d S. K . P u n t o n i. "Customer

(2008): 419-132. W alker, R. B. "Advertising in London Newspa

Empowerment in the Digital Age." loiirnal of

Advertising Research 56,1 (2016): 4-8. pers, 1650-1750." Business History 15, 2 (1973):

N evett , T. "London's Early Advertising Agents."

112-130.

Journal of Advertising Histonj 1,1 (1977): 15-17.

B erg , M ., and H . C liff o r d . "Selling Consumption

in the Eighteenth Century: Advertising and the N orris , V. P. "Advertising History: According to W engrow , D. "Prehistories of C om m odity

Trade Card in Britain and France." Cultural and the Textbooks." Journal of Advertising 9, 3 (1980): Branding." Current Anthropology 49, 1 (2008):

Social History 4,2 (2007): 145-170. 3-11. 7-34.

B r in k , E., and W. K e lle y . The Management of Pro Packard, V. The Hidden Persuaders. New York: W ood, J. P. The Story of Advertising. New York:

motion. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hail, 1963. David McKay, 1957. Ronald Press, 1958.

244 JOURnHL OF flOUERTISIflG RESEARCH Septem ber 2017

Copyright of Journal of Advertising Research is the property of Warc LTD and its content

may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright

holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for

individual use.

You might also like

- Case Study: Swiss PrecisionDocument3 pagesCase Study: Swiss PrecisionHajnalka RemeteNo ratings yet

- WP-SuppChainBenchmarking 2013Document36 pagesWP-SuppChainBenchmarking 2013Hajnalka RemeteNo ratings yet

- Effective 20 AdvertisingDocument19 pagesEffective 20 AdvertisingHajnalka RemeteNo ratings yet

- 4-7-Slogans Used by Indian Brands A BriefDocument15 pages4-7-Slogans Used by Indian Brands A BriefHajnalka RemeteNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- HoneymoonDocument12 pagesHoneymoonapi-3801537No ratings yet

- 2012 Bee GuideDocument32 pages2012 Bee Guidesmswamy100% (1)

- Cynthia-c-davidson-23-Diagram WorkDocument59 pagesCynthia-c-davidson-23-Diagram WorkFilippo Maria DoriaNo ratings yet

- TOI Bangalore 27-5-2023Document28 pagesTOI Bangalore 27-5-2023Ajay AhireNo ratings yet

- Out (Magazine) - WikipediaDocument45 pagesOut (Magazine) - WikipediaMatty A.No ratings yet

- Uncle Jack Bakonzi SampleDocument9 pagesUncle Jack Bakonzi SampleLeonor MazaNo ratings yet

- Definition of A Report TextDocument5 pagesDefinition of A Report TextZain Ikhsan FadilahNo ratings yet

- 2019-02-01 Aperture PDFDocument140 pages2019-02-01 Aperture PDFCarlos Salazar100% (1)

- History of Print MediaDocument24 pagesHistory of Print MediaLery Dulay50% (2)

- Internship Report As Human Resources TraineeDocument17 pagesInternship Report As Human Resources TraineeAnushka SinghNo ratings yet

- Indian Journalism-18th To 19th CenturyuDocument2 pagesIndian Journalism-18th To 19th CenturyuJanardhan Juvvigunta JJNo ratings yet

- Ajay Tyagi: Publications Journalist Name Landline WiresDocument20 pagesAjay Tyagi: Publications Journalist Name Landline WiresRiya ShahNo ratings yet

- Assuntos de Inglês Por NívelDocument20 pagesAssuntos de Inglês Por NívelTeacher JoeyNo ratings yet

- The Empress of Frozen Custard & Ninety-Nine Other Poems by Jorge Guitart Book PreviewDocument18 pagesThe Empress of Frozen Custard & Ninety-Nine Other Poems by Jorge Guitart Book PreviewBlazeVOX [books]No ratings yet

- Resume 2011 - Patrick J. SvitekDocument1 pageResume 2011 - Patrick J. SvitekPatrick SvitekNo ratings yet

- How To Write A Magazine FeatureDocument5 pagesHow To Write A Magazine FeaturerichiepeeNo ratings yet

- Kelsey Collisi's ResumeDocument1 pageKelsey Collisi's ResumeMax DrizinNo ratings yet

- Level of CommunicaitnDocument32 pagesLevel of CommunicaitnSimantoPreeom100% (1)

- De Thi THPT QG 2019 403Document5 pagesDe Thi THPT QG 2019 403Hồ Viết TiênNo ratings yet

- Fashion Magazine Codes and ConventionsDocument6 pagesFashion Magazine Codes and ConventionsSaja Kamareddine100% (1)

- Music Magazines Mojo IndustryDocument3 pagesMusic Magazines Mojo IndustryMrs Downie100% (1)

- Oral Assessment 1Document6 pagesOral Assessment 1carla soaresNo ratings yet

- Cubs Name List 2021-2022Document8 pagesCubs Name List 2021-2022Gayathri SenthilmuruganNo ratings yet

- Curating by Numbers - Lucy Lippard's Tate TalkDocument7 pagesCurating by Numbers - Lucy Lippard's Tate TalkSaisha Grayson-KnothNo ratings yet

- PEMBETULANDocument6 pagesPEMBETULANAdam Krisna Saeful ArifNo ratings yet

- Print Media - Its Merits & DemeritsDocument57 pagesPrint Media - Its Merits & DemeritsMayur Agarwal100% (1)

- Dilbert - WikipediaDocument12 pagesDilbert - WikipediaRudra Pradeepta Sharma KNo ratings yet

- Advertising Semiotics Make Mine MilkDocument12 pagesAdvertising Semiotics Make Mine MilkDavinia Obedih100% (1)

- VA4014 - Editorial Design - Presentation PDFDocument34 pagesVA4014 - Editorial Design - Presentation PDFIoana Nestorescu-BalcestiNo ratings yet

- Literary Journalism and Reportage As A Form of Creative Non-FictionDocument11 pagesLiterary Journalism and Reportage As A Form of Creative Non-FictionAbbygailNo ratings yet