Professional Documents

Culture Documents

How To Read A Paper

Uploaded by

Wyz ClassOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

How To Read A Paper

Uploaded by

Wyz ClassCopyright:

Available Formats

Education and debate

How to read a paper

Statistics for the non-statistician. I: Different types of data

need different statistical tests

This is the As medicine leans increasingly on mathematics no

fourth in a clinician can afford to leave the statistical aspects of Summary points

series of 10 a paper to the “experts.” If you are numerate, try the

articles “Basic Statistics for Clinicians” series in the Canadian

In assessing the choice of statistical tests in a

introducing Medical Association Journal,1-4 or a more mainstream

paper, first consider whether groups were

non-experts to statistical textbook.5 If, on the other hand, you find sta-

analysed for their comparability at baseline

finding medical tistics impossibly difficult, this article and the next in

articles and this series give a checklist of preliminary questions to Does the test chosen reflect the type of data

assessing their help you appraise the statistical validity of a paper. analysed (parametric or non-parametric, paired

value or unpaired)?

Have the authors set the scene correctly?

Unit for Has a two tailed test been performed whenever

Evidence-Based Have they determined whether their groups are comparable, the effect of an intervention could conceivably be

Practice and Policy, and, if necessary, adjusted for baseline differences?

Department of a negative one?

Primary Care and Most comparative clinical trials include either a table

Population or a paragraph in the text showing the baseline charac- Have the data been analysed according to the

Sciences, University

College London

teristics of the groups being studied. Such a table original study protocol?

Medical School/ should show that the intervention and control groups

Royal Free Hospital are similar in terms of age and sex distribution and key If obscure tests have been used, do the authors

School of Medicine,

Whittington prognostic variables (such as the average size of a can- justify their choice and provide a reference?

Hospital, London cerous lump). Important differences in these character-

N19 5NF istics, even if due to chance, can pose a challenge to

Trisha Greenhalgh,

your interpretation of results. In this situation, numbers for a particular sample of cases, but we would

senior lecturer

adjustments can be made to allow for these differences be completely unable to interpret the result. The same

p.greenhalgh@ucl.

ac.uk and hence strengthen the argument.6 would apply if we labelled the property “liking for x”

with 1 = not at all, 2 = a bit, and 3 = a lot. Again, we

BMJ 1997;315:364–6 What sort of data have they got, and have they used could calculate the “average liking,” but the numerical

appropriate statistical tests? result would be uninterpretable unless we knew that the

Numbers are often used to label the properties of difference between “not at all” and “a bit” was exactly

things. We can assign a number to represent our height, the same as the difference between “a bit” and “a lot.”

weight, and so on. For properties like these, the All statistical tests are either parametric (that is, they

measurements can be treated as actual numbers. We assume that the data were sampled from a particular

can, for example, calculate the average weight and form of distribution, such as a normal distribution) or

height of a group of people by averaging the measure- non-parametric (they make no such assumption). In

ments. But consider an example in which we use num- general, parametric tests are more powerful than non-

bers to label the property “city of origin,” where parametric ones and so should be used if possible.

1 = London, 2 = Manchester, 3 = Birmingham, and so Non-parametric tests look at the rank order of the

on. We could still calculate the average of these values (which one is the smallest, which one comes

next, and so on) and ignore the absolute differences

between them. As you might imagine, statistical

significance is more difficult to show with non-

parametric tests, and this tempts researchers to use

statistics such as the r value inappropriately. Not only is

the r value (parametric) easier to calculate than its

non-parametric equivalent but it is also much more

likely to give (apparently) significant results.

Unfortunately, it will give a spurious estimate of the

significance of the result, unless the data are appropri-

ate to the test being used. More examples of paramet-

ric tests and their non-parametric equivalents are given

in table 1.

Another consideration is the shape of the distribu-

tion from which the data were sampled. When I was at

school, my class plotted the amount of pocket money

received against the number of children receiving that

PETER BROWN

amount. The results formed a histogram the same

shape as figure 1—a “normal” distribution. (The term

“normal” refers to the shape of the graph and is used

364 BMJ VOLUME 315 9 AUGUST 1997

Education and debate

Table 1 Some commonly used statistical tests

Example of equivalent

Parametric test non-parametric test Purpose of test Example

Two sample (unpaired) t test Mann-Whitney U test Compares two independent samples drawn from To compare girls’ heights with boys’

the same population heights

One sample (paired) t test Wilcoxon matched pairs test Compares two sets of observations on a single To compare weight of infants before and

sample after a feed

One way analysis of variance Kruskall-Wallis analysis of Effectively, a generalisation of the paired t or To determine whether plasma glucose

(F test) using total sum of variance by ranks Wilcoxon matched pairs test where three or more level is higher one hour, two hours, or

squares sets of observations are made on a single sample three hours after a meal

Two way analysis of variance Two way analysis of variance As above, but tests the influence (and In the above example, to determine if the

by ranks interaction) of two different covariates results differ in male and female subjects

÷2 test Fisher’s exact test Tests the null hypothesis that the distribution of To assess whether acceptance into

a discontinuous variable is the same in two (or medical school is more likely if the

more) independent samples applicant was born in Britain

Product moment correlation Spearman’s rank correlation Assesses the strength of the straight line To assess whether and to what extent

coefficient (Pearson’s r) coefficient (ró) association between two continuous variables. plasma HbA1 concentration is related to

plasma triglyceride concentration in

diabetic patients

Regression by least squares Non-parametric regression Describes the numerical relation between two To see how peak expiratory flow rate

method (various tests) quantitative variables, allowing one value to be varies with height

predicted from the other

Multiple regression by least Non-parametric regression Describes the numerical relation between a To determine whether and to what extent a

squares method (various tests) dependent variable and several predictor person’s age, body fat, and sodium intake

variables (covariates) determine their blood pressure

because many biological phenomena show this pattern Are the data analysed according to the original protocol?

of distribution). Some biological variables such as body If you play coin toss with someone, no matter how far

weight show “skew normal” distribution, as shown in you fall behind, there will come a time when you are

figure 2. (Figure 2 shows a negative skew, whereas body one ahead. Most people would agree that to stop the

weight would be positively skewed. The average adult game then would not be a fair way to play. So it is with

male body weight is 70 kg, and people exist who weigh research. If you make it inevitable that you will (eventu-

140 kg, but nobody weighs less than nothing, so the ally) get an apparently positive result you will also

graph cannot possibly be symmetrical.) make it inevitable that you will be misleading yourself

Non-normal (skewed) data can sometimes be about the justice of your case.7 (Terminating an

transformed to give a graph of normal shape by intervention trial prematurely for ethical reasons when

performing some mathematical transformation (such subjects in one arm are faring particularly badly is a

as using the variable’s logarithm, square root, or recip- different matter and is discussed elsewhere.7)

rocal). Some data, however, cannot be transformed into Raking over your data for “interesting results” (ret-

a smooth pattern. For a very readable discussion of the rospective subgroup analysis) can lead to false conclu-

normal distribution see chapter 7 of Martin Bland’s

Introduction to Medical Statistics.5

Deciding whether data are normally distributed is

Frequency

not an academic exercise, since it will determine what

type of statistical tests to use. For example, linear

regression will give misleading results unless the points

on the scatter graph form a particular distribution

about the regression line—that is, the residuals (the

perpendicular distance from each point to the line)

should themselves be normally distributed. Transform-

ing data to achieve a normal distribution (if this is

indeed achievable) is not cheating: it simply ensures

that data values are given appropriate emphasis in

Number

assessing the overall effect. Using tests based on the

Fig 1 Normal curve

normal distribution to analyse non-normally distrib-

uted data, however, is definitely cheating.

If the authors have used obscure statistical tests, why have

Frequency

they done so and have they referenced them?

The number of possible statistical tests sometimes

seems infinite. In fact, most statisticians could survive

with a formulary of about a dozen. The rest should

generally be reserved for special indications. If the

paper you are reading seems to describe a standard set

of data which have been collected in a standard way,

but the test used has an unpronounceable name and is

not listed in a basic statistics textbook, you should smell

a rat. The authors should, in such circumstances, state Number

why they have used this test, and give a reference (with Fig 2 Skewed curve

page numbers) for a definitive description of it.

BMJ VOLUME 315 9 AUGUST 1997 365

Education and debate

sions.8 In an early study on the use of aspirin in increase it. Hence, your statistical analysis should, in

preventing stroke, the results showed a significant general, test the hypothesis that either high or low val-

effect in both sexes combined, and a retrospective sub- ues in your dataset have arisen by chance. In the

group analysis seemed to show that the effect was con- language of the statisticians, this means you need a two

fined to men.9 This conclusion led to aspirin being tailed test, unless you have very convincing evidence

withheld from women for many years, until the results that the difference can only be in one direction.

of other studies10 showed that this subgroup effect was

spurious.

This and other examples are included in Oxman Were “outliers” analysed with both common sense and

and Guyatt’s, “A consumer’s guide to subgroup appropriate statistical adjustments?

analysis,” which reproduces a useful checklist for decid- Unexpected results may reflect idiosyncrasies in the

ing whether apparent subgroup differences are real.11 subject (for example, unusual metabolism), errors in

measurement (faulty equipment), errors in inter-

pretation (misreading a meter reading), or errors in

Paired data, tails, and outliers calculation (misplaced decimal points). Only the first of

Were paired tests performed on paired data? these is a “real” result which deserves to be included in

Students often find it difficult to decide whether to use the analysis. A result which is many orders of

a paired or unpaired statistical test to analyse their magnitude away from the others is less likely to be

data. There is no great mystery about this. If you meas- genuine, but it may be so. A few years ago, while doing

ure something twice on each subject—for example, a research project, I measured several different

blood pressure measured when the subject is lying and hormones in about 30 subjects. One subject’s growth

when standing—you will probably be interested not hormone levels came back about 100 times higher

just in the average difference of lying versus standing than everyone else’s. I assumed this was a transcription

blood pressure in the entire sample, but in how much error, so I moved the decimal point two places to the

each individual’s blood pressure changes with position. left. Some weeks later, I met the technician who had

In this situation, you have what is called “paired” data, analysed the specimens and he asked, “Whatever hap-

because each measurement beforehand is paired with pened to that chap with acromegaly?”

a measurement afterwards. Statistically correcting for outliers (for example, to

In this example, it is using the same person on both modify their effect on the overall result) requires

occasions which makes the pairings, but there are sophisticated analysis and is covered elsewhere.6

other possibilities (for example, any two measurements

of bed occupancy made of the same hospital ward). In

these situations, it is likely that the two sets of values will

be significantly correlated (for example, my blood The articles in this series are excerpts from How to

pressure next week is likely to be closer to my own read a paper: the basics of evidence based medicine. The

blood pressure last week than to the blood pressure of book includes chapters on searching the literature

a randomly selected adult last week). In other words, we and implementing evidence based findings. It can

be ordered from the BMJ Bookshop: tel 0171 383

would expect two randomly selected paired values to

6185/6245; fax 0171 383 6662. Price £13.95 UK

be closer to each other than two randomly selected members, £14.95 non-members.

unpaired values. Unless we allow for this, by carrying

out the appropriate paired sample tests, we can end up

with a biased estimate of the significance of our results.

I am grateful to Mr John Dobby for educating me on statistics

Was a two tailed test performed whenever the effect of an and for repeatedly checking and amending this article. Respon-

intervention could conceivably be a negative one? sibility for any errors is mine alone.

The term “tail” refers to the extremes of the distri-

bution—the areas at the outer edges of the bell in figure

1 Guyatt G, Jaenschke R, Heddle, N, Cook D, Shannon H, Walter S. Basic

1. Let’s say that the graph represents the diastolic blood statistics for clinicians. 1. Hypothesis testing. Can Med Assoc J

pressures of a group of people of which a random 1995;152:27-32.

2 Guyatt G, Jaenschke R, Heddle, N, Cook D, Shannon H, Walter S. Basic

sample are about to be put on a low sodium diet. If a statistics for clinicians. 2. Interpreting study results: confidence intervals.

low sodium diet has a significant lowering effect on Can Med Assoc J 1995;152:169-73.

blood pressure, subsequent blood pressure measure- 3 Jaenschke R, Guyatt G, Shannon H, Walter S, Cook D, Heddle, N. Basic

statistics for clinicians: 3. Assessing the effects of treatment: measures of

ments on these subjects would be more likely to lie association. Can Med Assoc J 1995;152:351-7.

within the left tail of the graph. Hence we would 4 Guyatt G, Walter S, Shannon H, Cook D, Jaenschke R, Heddle, N. Basic

statistics for clinicians. 4. Correlation and regression. Can Med Assoc J

analyse the data with statistical tests designed to show 1995;152:497-504.

whether unusually low readings in this patient sample 5 Bland M. An introduction to medical statistics. Oxford: Oxford University

were likely to have arisen by chance. Press, 1987.

6 Altman D. Practical statistics for medical research. London: Chapman and

But on what grounds may we assume that a low Hall, 1995.

sodium diet could only conceivably put blood pressure 7 Hughes MD, Pocock SJ. Stopping rules and estimation problems in clini-

cal trials. Statistics in Medicine 1987;7:1231-42.

down, but could never do the reverse, put it up? Even if 8 Stewart LA, Parmar MKB. Bias in the analysis and reporting of

there are valid physiological reasons in this particular randomized controlled trials. Int J Health Technology Assessment

example, it is certainly not good science always to 1996;12:264-75.

9 Canadian Cooperative Stroke Group. A randomised trial of aspirin and

assume that you know the direction of the effect which sulfinpyrazone in threatened stroke. N Engl J Med 1978;299:53-9.

your intervention will have. A new drug intended to 10 Antiplatelet Trialists Collaboration. Secondary prevention of vascular

disease by prolonged antiplatelet treatment. BMJ 1988;296:320-1.

relieve nausea might actually exacerbate it, or an 11 Oxman, AD, Guyatt GH. A consumer’s guide to subgroup analysis. Ann

educational leaflet intended to reduce anxiety might Intern Med 1992;116:79-84.

366 BMJ VOLUME 315 9 AUGUST 1997

You might also like

- Hypothesis Testing: An Intuitive Guide for Making Data Driven DecisionsFrom EverandHypothesis Testing: An Intuitive Guide for Making Data Driven DecisionsNo ratings yet

- Arlete's Notes For Step 3 - USMLE ForumsDocument14 pagesArlete's Notes For Step 3 - USMLE ForumsWyz Class100% (3)

- Likert Scales: How To (Ab) Use Them Susan JamiesonDocument8 pagesLikert Scales: How To (Ab) Use Them Susan JamiesonFelipe Santana LopesNo ratings yet

- Statics and Mechnics of StructuresDocument511 pagesStatics and Mechnics of StructuresPrabu RengarajanNo ratings yet

- Practice Homework SetDocument58 pagesPractice Homework SetTro emaislivrosNo ratings yet

- CSUKs Algorithm Writing Guide and WorkbookDocument73 pagesCSUKs Algorithm Writing Guide and Workbooksaimaagarwal220508No ratings yet

- Statistics For The Non Statistician (Greenhalgh 1997)Document7 pagesStatistics For The Non Statistician (Greenhalgh 1997)Bextiyar BayramlıNo ratings yet

- Choosing Stadistical Test. International Journal of Ayurveda Research 2010Document5 pagesChoosing Stadistical Test. International Journal of Ayurveda Research 2010Ernesto J. Rocha ReyesNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1-Introduction To Non-Parametric StatisticsDocument10 pagesChapter 1-Introduction To Non-Parametric StatisticsMarben OrogoNo ratings yet

- Module 004 - Parametric and Non-ParametricDocument12 pagesModule 004 - Parametric and Non-ParametricIlovedocumintNo ratings yet

- Likert Scales, Levels of Measurement and The 'Laws' of Statistics PDFDocument8 pagesLikert Scales, Levels of Measurement and The 'Laws' of Statistics PDFLoebizMudanNo ratings yet

- Non Parametric TestDocument16 pagesNon Parametric TestVIKAS DOGRA100% (1)

- ST1506 063Document6 pagesST1506 063joanna intiaNo ratings yet

- Descriptive Statisitics Sir EricDocument46 pagesDescriptive Statisitics Sir Ericwendydeveyra7No ratings yet

- Lab1-7 - Non-Parametric - TutorsDocument7 pagesLab1-7 - Non-Parametric - TutorsAlan SerranoNo ratings yet

- Steps Quantitative Data AnalysisDocument4 pagesSteps Quantitative Data AnalysisShafira Anis TamayaNo ratings yet

- Statistical Precision of Information Retrieval Evaluation: Gordon V. Cormack and Thomas R. LynamDocument8 pagesStatistical Precision of Information Retrieval Evaluation: Gordon V. Cormack and Thomas R. LynamMauricioKuchtaNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id2952685Document30 pagesSSRN Id2952685zeeshanNo ratings yet

- Application of Statistical Tools For Data Analysis and Interpretation in CropsDocument10 pagesApplication of Statistical Tools For Data Analysis and Interpretation in CropsAndréFerrazNo ratings yet

- Emerging Trends & Analysis 1. What Does The Following Statistical Tools Indicates in ResearchDocument7 pagesEmerging Trends & Analysis 1. What Does The Following Statistical Tools Indicates in ResearchMarieFernandesNo ratings yet

- Statistical Analysis: Eileen D. DagatanDocument30 pagesStatistical Analysis: Eileen D. Dagataneileen del dagatanNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA)Document41 pagesUnit 5 Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA)Shamie Singh100% (1)

- Analysing Data Using SpssDocument94 pagesAnalysing Data Using SpssSandeep Bhatt100% (1)

- Name: Hasnain Shahnawaz REG#: 1811265 Class: Bba-5B Subject: Statistical Inferance Assignment 1 To 10Document38 pagesName: Hasnain Shahnawaz REG#: 1811265 Class: Bba-5B Subject: Statistical Inferance Assignment 1 To 10kazi ibiiNo ratings yet

- Statistical TestsDocument9 pagesStatistical Testsalbao.elaine21No ratings yet

- PIIS1751722223001750Document5 pagesPIIS1751722223001750anitn2020No ratings yet

- New Normal MPA Statistics Chapter 2Document15 pagesNew Normal MPA Statistics Chapter 2Mae Ann GonzalesNo ratings yet

- T Test Literature ReviewDocument6 pagesT Test Literature Reviewafdtsypim100% (1)

- Larose 3e Online Ch14 HiresDocument67 pagesLarose 3e Online Ch14 HiresGiulia AngNo ratings yet

- Quantitative Methods or Quantitative All QuizDocument17 pagesQuantitative Methods or Quantitative All QuizHiro GamerNo ratings yet

- Bio StatisticsDocument20 pagesBio StatisticskatyNo ratings yet

- Rma Statistical TreatmentDocument5 pagesRma Statistical Treatmentarnie de pedroNo ratings yet

- How To Select Appropriate Statistical Test?: Technical NotesDocument3 pagesHow To Select Appropriate Statistical Test?: Technical NotesFathin NabillaNo ratings yet

- Unit 2.3 Basic of Testing HypothesisDocument25 pagesUnit 2.3 Basic of Testing HypothesisHiba MohammedNo ratings yet

- Siegel57Nonparametric PDFDocument8 pagesSiegel57Nonparametric PDFTarisna AryantiNo ratings yet

- Ekran Resmi 2024-03-04 - 09.59.44Document1 pageEkran Resmi 2024-03-04 - 09.59.44Dlko Zakho88No ratings yet

- Parametric and Non-Parametric TestsDocument2 pagesParametric and Non-Parametric TestsM S Sridhar100% (1)

- Statistics For A2 BiologyDocument9 pagesStatistics For A2 BiologyFaridOraha100% (1)

- Sec 1 Quantitative ResearchDocument7 pagesSec 1 Quantitative ResearchtayujimmaNo ratings yet

- RM AssumptionsDocument7 pagesRM AssumptionsWahyu HidayatNo ratings yet

- Factor AnalysisDocument14 pagesFactor AnalysissamiratNo ratings yet

- Equidistance of Likert-Type Scales and Validation of Inferential Methods Using Experiments and SimulationsDocument13 pagesEquidistance of Likert-Type Scales and Validation of Inferential Methods Using Experiments and SimulationsIsidore Jan Jr. RabanosNo ratings yet

- Capraro Et Al 2001 Measurement Error of Scores On The Mathematics Anxiety Rating Scale Across StudiesDocument14 pagesCapraro Et Al 2001 Measurement Error of Scores On The Mathematics Anxiety Rating Scale Across StudiesInes DuarteNo ratings yet

- Tips and Tricks For Analyzing Non-Normal DataDocument3 pagesTips and Tricks For Analyzing Non-Normal Databetapark solutionNo ratings yet

- Bernard F Dela Vega PH 1-1Document5 pagesBernard F Dela Vega PH 1-1BernardFranciscoDelaVegaNo ratings yet

- An Animated Guide: Matching Test and Control Subjects: Russell Lavery, Independent ConsultantDocument21 pagesAn Animated Guide: Matching Test and Control Subjects: Russell Lavery, Independent Consultantlion kingNo ratings yet

- HypothesisDocument30 pagesHypothesisSargun KaurNo ratings yet

- Chi-Square Test: Understanding ResearchDocument1 pageChi-Square Test: Understanding ResearchTommy Winahyu PuriNo ratings yet

- Test of NormalityDocument7 pagesTest of NormalityDarlene OrbetaNo ratings yet

- Statistics in Research 2018Document8 pagesStatistics in Research 2018jamaeNo ratings yet

- Practical StatisticsDocument26 pagesPractical Statisticssunilverma2010No ratings yet

- Lecture 12.1 MA SR GuidelinesDocument43 pagesLecture 12.1 MA SR GuidelinesArokiasamy JairishNo ratings yet

- Para and Non-ParaDocument4 pagesPara and Non-ParaAldye XNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document16 pagesChapter 2AndreaNo ratings yet

- COMPREHENSIVE REPORT-Educational StatisticsDocument5 pagesCOMPREHENSIVE REPORT-Educational StatisticsMarjun PachecoNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Descriptive StatisticsDocument5 pagesLiterature Review On Descriptive Statisticstug0l0byh1g2100% (1)

- Factor Analysis Easy Definition - Statistics How ToDocument13 pagesFactor Analysis Easy Definition - Statistics How ToEmmanuel PaulinoNo ratings yet

- Likert Scales, Levels of Measurement and The Laws'' 2010Document9 pagesLikert Scales, Levels of Measurement and The Laws'' 201012719789mNo ratings yet

- Sample Size Guideline For Correlation AnalysisDocument10 pagesSample Size Guideline For Correlation AnalysisambersNo ratings yet

- Organization of TermsDocument26 pagesOrganization of TermsAlemor AlviorNo ratings yet

- Data Analysis Chp9 RMDocument9 pagesData Analysis Chp9 RMnikjadhavNo ratings yet

- How To Write A World-Class PaperDocument93 pagesHow To Write A World-Class PaperLuiggi FayadNo ratings yet

- ITE Exam NotesDocument2 pagesITE Exam NotesWyz ClassNo ratings yet

- AS-4, PWV, Kim Et Al, 2015 and CAC Sleep Duration Sleep Quality and Markers PDFDocument8 pagesAS-4, PWV, Kim Et Al, 2015 and CAC Sleep Duration Sleep Quality and Markers PDFWyz ClassNo ratings yet

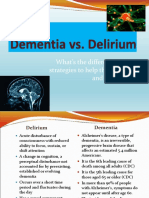

- Dementia and DeliriumDocument20 pagesDementia and DeliriumWyz ClassNo ratings yet

- A Step by Step Guide To Writing A Scientific ManuscriptDocument18 pagesA Step by Step Guide To Writing A Scientific ManuscriptFatwa IslamiNo ratings yet

- As-3, PWV, Tsai-Chen Tsai Et Al, Jan 2014Document6 pagesAs-3, PWV, Tsai-Chen Tsai Et Al, Jan 2014Wyz ClassNo ratings yet

- NCLEX Study Notes 20080924Document61 pagesNCLEX Study Notes 20080924Shan Shan He100% (6)

- Pat Manual Jan11Document32 pagesPat Manual Jan11Wyz ClassNo ratings yet

- Scientific Method IntroDocument45 pagesScientific Method Introapi-236069914No ratings yet

- ATP III Guideline KolesterolDocument6 pagesATP III Guideline KolesterolRakasiwi GalihNo ratings yet

- Heart Failure: Living With A Hurting HeartDocument44 pagesHeart Failure: Living With A Hurting HeartWyz ClassNo ratings yet

- PWV Quick Guide XcelDocument2 pagesPWV Quick Guide XcelWyz ClassNo ratings yet

- DementiaDocument53 pagesDementiaWyz ClassNo ratings yet

- Physio - Neuro - Review - Stacey Trent - 2005Document40 pagesPhysio - Neuro - Review - Stacey Trent - 2005Wyz ClassNo ratings yet

- Central Nervous System Part, Physio and PathoDocument40 pagesCentral Nervous System Part, Physio and PathoWyz ClassNo ratings yet

- Nerves of The Lower LimbDocument8 pagesNerves of The Lower LimbWyz ClassNo ratings yet

- Lecture 19aDocument24 pagesLecture 19aWyz ClassNo ratings yet

- Body Changes in AgingDocument37 pagesBody Changes in AgingWyz ClassNo ratings yet

- Vessels of The Lower ExtremityDocument39 pagesVessels of The Lower ExtremityWyz ClassNo ratings yet

- Scientific Method IntroDocument45 pagesScientific Method Introapi-236069914No ratings yet

- DementiaDocument53 pagesDementiaWyz ClassNo ratings yet

- Drugs of Autonomic Nervous SystemDocument34 pagesDrugs of Autonomic Nervous SystemWyz Class100% (1)

- Chapter 001Document26 pagesChapter 001Wyz ClassNo ratings yet

- Seizure Disorders LectureDocument52 pagesSeizure Disorders LectureWyz ClassNo ratings yet

- DementiaDocument53 pagesDementiaWyz ClassNo ratings yet

- Nursing Myocardia InfarctionDocument22 pagesNursing Myocardia InfarctionWyz ClassNo ratings yet

- Daftar Obat Anti Hipertensi PDFDocument7 pagesDaftar Obat Anti Hipertensi PDFPietra Jaya100% (1)

- Biochemistry 3Document3 pagesBiochemistry 3Wyz ClassNo ratings yet

- Swan SoftDocument90 pagesSwan Softandreeaoana45No ratings yet

- Focus Group Interview TranscriptDocument5 pagesFocus Group Interview Transcriptapi-322622552No ratings yet

- CSCI 240 Lecture NotesDocument14 pagesCSCI 240 Lecture NotesOkiring SilasNo ratings yet

- AutoevaluaciÓn Álgebra Superior IDocument7 pagesAutoevaluaciÓn Álgebra Superior IjoseNo ratings yet

- 7 2 Using FunctionsDocument7 pages7 2 Using Functionsapi-332361871No ratings yet

- ENGLISH - Subject Verb Agreement Grammar Revision Guide and Quick Quiz Powerpoint AustralianDocument11 pagesENGLISH - Subject Verb Agreement Grammar Revision Guide and Quick Quiz Powerpoint AustralianRogelio LadieroNo ratings yet

- Gas Ab 1Document24 pagesGas Ab 1John Leonard FazNo ratings yet

- Expected Price Functionof Price SensitivityDocument10 pagesExpected Price Functionof Price SensitivityMr PoopNo ratings yet

- Astm D4065 20Document5 pagesAstm D4065 20Pulinda KasunNo ratings yet

- History of MathematicsDocument38 pagesHistory of MathematicsSreekanth ReddyNo ratings yet

- Essay On Options Strategies For Financial TransactionsDocument5 pagesEssay On Options Strategies For Financial TransactionsKimkhorn LongNo ratings yet

- Bourne, DavidW. A. - Strauss, Steven - Mathematical Modeling of Pharmacokinetic Data (2018, CRC Press - Routledge)Document153 pagesBourne, DavidW. A. - Strauss, Steven - Mathematical Modeling of Pharmacokinetic Data (2018, CRC Press - Routledge)GuillermoNo ratings yet

- Lectures On Communicative AlgebraDocument64 pagesLectures On Communicative Algebramimi_loveNo ratings yet

- The Concise Academy: Guess For All Punjab Board Exam 2021 (ALP)Document6 pagesThe Concise Academy: Guess For All Punjab Board Exam 2021 (ALP)mudassirNo ratings yet

- Physical Sciences PDFDocument51 pagesPhysical Sciences PDFfarooqi111No ratings yet

- Physics Paper 3 For SPM 2019 2020 - AnswerDocument35 pagesPhysics Paper 3 For SPM 2019 2020 - AnswerAzman SelamatNo ratings yet

- Integrated Curriculum For Secondary Schools: Mathematics Form 2Document139 pagesIntegrated Curriculum For Secondary Schools: Mathematics Form 2Izawaty IsmailNo ratings yet

- ReMaDDer Software Tutorial (v2.0) - Fuzzy Match Record Linkage and Data DeduplicationDocument59 pagesReMaDDer Software Tutorial (v2.0) - Fuzzy Match Record Linkage and Data DeduplicationmatalabNo ratings yet

- Multivariate Analysis: Subject: Research MethodologyDocument14 pagesMultivariate Analysis: Subject: Research MethodologysangamNo ratings yet

- Chap. 3 pdf2Document38 pagesChap. 3 pdf2Arvin Grantos LaxamanaNo ratings yet

- Owners Role in Project SuccessDocument342 pagesOwners Role in Project SuccessJorge Bismarck Jimenez BarruosNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan - AmortizationDocument4 pagesLesson Plan - Amortizationapi-327991016100% (1)

- Effect of Impeller Blades Number On The Performance of A Centrifugal PumpDocument11 pagesEffect of Impeller Blades Number On The Performance of A Centrifugal Pumpdodo1986No ratings yet

- Research Proposal 1 PDFDocument5 pagesResearch Proposal 1 PDFMunem BushraNo ratings yet

- Mock Test - 1Document8 pagesMock Test - 1Anish JoshiNo ratings yet

- Engineering Failure Analysis-Crack GrowthDocument27 pagesEngineering Failure Analysis-Crack GrowthchandruNo ratings yet

- Continuous ProbabilityDocument38 pagesContinuous ProbabilitysarahNo ratings yet