Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Should Plain Radiographs Persist or Be Replaced by Alternative Scans For Imaging of Acute Painful Nontraumatic Abdominal

Uploaded by

Shira michaelOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Should Plain Radiographs Persist or Be Replaced by Alternative Scans For Imaging of Acute Painful Nontraumatic Abdominal

Uploaded by

Shira michaelCopyright:

Available Formats

RESEARCH PAPER

Should plain radiographs persist or

be replaced by alternative scans for

imaging of acute painful non-traumatic

abdominal pain?

Purpose: Acute non-traumatic abdominal pain (ANTAP) is a frequent presentation at the emergency department

(ED). Plain abdominal radiographs (PAR's) were historically the principal imaging tool.

The objective of this study was to determine whether PAR's are still in use for ANTAP diagnosis. The other objective

was to determine whether PAR’s stood-alone or were they a redundant step delaying the definitive imaging test. When

CT scans were added to PAR's the sensitivity and specificity of the two modalities were compared.

Methods: A report of a retrospective study conducted at an 800-bed hospital ED between 01.06.2014 and

30.06.2014. All patients aged 15 and above who presented with ANTAP and referred first for PAR’s were included.

Traumatic, obstetric, gynaecologic cases were excluded. The discharge diagnosis was considered the gold standard.

Main findings: The study included 756 patients. 375 (49.6%) were males, 381 (50.4%) were females. The age range

was 15 to 92 yrs. Mean age was 46 yrs. The most common presentation was an unclassified abdominal pain in 516

(68%). PAR's were requested alone for 594 (78.5%) and followed afterwards by Conventional CT in 103 (13.6%).

Low dose CT was added for 33 (4.3%). The sensitivity of PAR's and CT for urinary stones was 32.8% and 91.3%

respectively. The sensitivity of PAR's and CT for intestinal obstruction was 50% and 83.3% respectively.

Conclusion: PAR's are still in use as a one-stop shop for imaging the majority of patients presenting with ANTAP.

In patients who had both CT and PAR's, there was a low PAR's sensitivity leading to poor congruence in diagnosing

abnormal cases. However, CT delivered a higher radiation dose. There is a need to replace the conventional CT and

PAR's for ANTAP imaging.

KEYWORDS: plain abdominal radiographs acute non-traumatic abdominal pain

Abbreviations: ANTAP: acute non-traumatic CT and US followed a reverse rising utilization

M Abd El Bagi1*, Badr

abdominal pain; CT: computed tomography; pattern [2]. According to Smith and Hall’s

Mutairi1, Sami

ED: emergency department; LDCT: low literature review of PAR’s use, 25% of the

radiographs showed some abnormality but the

Alsolamy2, Mohamed

dose CT; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging;

mSv: milli sievert; PAR’s: plain abdominal majority of those findings were unrelated to the Alaizari1 , Sumaya

radiographs; ultra-LDCT: ultra-low dose CT; final diagnosis. Many workers have decided that Alrashid1, Ibrahim

US: ultrasound PAR’s have little value in the ED [5-7]. Alrashidi1, Naila

Shaheen3 & Mercia

The introduction of CT scanning had a

Introduction Reutener1

remarkable impact on diagnostic imaging.

Emergency department (ED) physicians 1

Diagnostic Imaging Department, King

Abdominal CT scans usually require the Abdulaziz Medical City, Riyadh,

are facing the challenge of handling acute Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

administration of contrast media via the oral,

non-traumatic abdominal pain (ANTAP) on 2

Emergency Medicine Department,

rectal or intravenous route which is a cost

daily bases [1-3]. Plain abdominal radiographs King Abdulaziz Medical City, Riyadh,

burden. CT exposes the patient to a higher dose Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

(PAR’s) were historically the only imaging test

of ionizing radiation which can increase the 3

Department of Biostatistics and

for abdominal emergencies [1]. Even after the Bioinformatics, King Abdullah

risk of cancer development [8]. An Australian

discovery of CT and MRI, Field declared that International Medical Research Centre,

study, reported a higher cancer incidence in King Saud Bin Abdulaziz University for

PAR’s are expected to maintain their superiority

those exposed to CT [9]. The recently used Health Sciences, Kingdom of Saudi

in demonstrating the bowel gas pattern for Arabia

low dose CT (LDCT) delivers much less mSv

many subsequent years [4]. *Author for correspondence:

compared to conventional enhanced CT [10].

drm_bagi@hotmail.com

In the last century, most patients with ANTAP Non-contrast LDCT has gained an increasing

would undergo PAR’s [2]. This rate has recently popularity for imaging renal colic [10]. Haller et

decreased to less than a quarter of imaged cases. al compared the results of PAR’s versus LDCT.

ISSN 1755-5191 Imaging Med. (2017) 9(6) 179

RESEARCH PAPER El Bagi MA, Mutairi B, Alsolamy S, Alaizari M, Alrasheed S, et al.

He concluded that “Patients who underwent The month was chosen to avoid the fasting

PAR’s needed more imaging in 38% of cases, periods and the feast season which may affect

while those who had low dose CT needed the clinical presentation pattern and frequencies

additional extra imaging in 4% of cases” [11]. of abdominal pain.

Fortunately, as the use of CT rapidly increases,

there is a parallel effort to manufacture lower Inclusion criteria

dose scanners and develop lower dose protocols All patients complaining of ANTAP of any

[11]. The industry has recently produced ultra- abdominal quadrant or internal organ as filtered

LDCT but not without limitations [12,13]. by the triage process were included if referred

Expectedly, these shortcomings will soon be for ANTAP alone at first. Those who had

overcome. subsequent imaging afterwards were included.

The guidelines for imaging of ANTAP are Exclusion criteria

widely debated by many authors [14-18] and Traumatic, gynaecologic, obstetric and

are regularly revised by the relevant authorities paediatric cases were excluded. Patients who

and groups [19,20]. However, the technologic had hospital admission, surgery or any imaging

advances may supersede such guidelines in the previous two weeks were excluded to

revisions. Excessive requisition of radiographs maintain the originality of the presentations.

and scans is not uncommon in some Middle Patients who had simultaneous requests for

East countries where there are expatriate other scans were also excluded.

practitioners who may tend to have a protective

tendency [21]. MRI has recently been used by Study design

some workers for imaging ANTAP particularly Only the written reports, and the discharge

in pregnant women [22]. notes, were reviewed. There was no attempt

to re-assess the images retrospectively. The

It is unknown whether PAR’s are still used triage notes and the discharge summaries were

or have been abandoned since the recent reviewed by the ED team members (SS and AZ)

application of the 4 hours ED clearance while the radiology reports were reviewed by the

restriction. The objective of this study was to radiologists (MA, BM, SA and IA).

determine whether PAR's are still in use for

ANTAP diagnosis presenting to the ED. The Outcome measures

other objective was to find out when PAR’s The outcome measure for this study was to

were used, did they stand-alone or were they a find the indications for PAR’s and how frequently

redundant step delaying the definitive imaging they were alone sufficient or otherwise. PAR’s

test. When CT scans were added to PAR's, the and CT sensitivity in this series were compared

sensitivity and specificity of the two modalities to the literature using the commonly presenting

were compared to see the congruence of PAR’s conditions namely intestinal obstruction

with CT results, and whether there is a need to and urinary calculi. Results included patient

call for alternatives for either modality. Unlike demographics, summarized proportions,

other studies, this work focusses only on those percentages, age mean and standard deviation.

sent initially for PAR’s alone. Our results have

The final discharge diagnosis from the ward or

answered the relevant questions raised.

ED was taken as the gold standard. Results were

Methods tabulated using counts with the corresponding

95% CI. We assessed the predictive power of

Setting PAR’s and CT by the sensitivity and specificity

The setting for this retrospective study was and their congruence of agreements by Kappa

an (ED) with 115 beds receiving more than statistics at 95% CI.

150,000 annual visits in an 800-bed tertiary

care centre. Institutional Review Board (IBR) Results

approval was obtained. Using our institution 15140 patients visited our ED department

database, all patients with the age of 15 or more during June 2014 with a variety of presentations.

who have attended the ED with ANTAP and PAR’s were the first requested imaging test

referred first or only for PAR’s during the period for 756 (4.9%) of them due to ANTAP. 375

from 01.06.2014 to 30.06.2014 were included. (49.6%) of those 756 patients were males, and

180 Imaging Med. (2017) 9(6)

Should plain radiographs persist or be replaced by alternative scans for imaging of

acute painful non-traumatic abdominal pain?

RESEARCH PAPER

381 (50.4%) were females. The age range was a non-specific abdominal pain in 516 (68%)

15 to 92 yrs. Mean age was 46 yrs. The most (TABLE 2). The second frequent presentation

frequent age group encountered was 20-39 was the organ-specific pain in 77 (10.1%).

years in 277 (36.6%), and the rarest was the Abdominal distension was the third request for

15-19 groups of 44 (5.8%) (TABLE 1). The 69 (9.1%). There was no request for biliary colic,

most encountered indication for PAR’s was appendicitis, pancreatitis, inflammatory bowel

disease, abscess, gynaecologic conditions or peptic

ulcers. The rarest order was for bowel ischemia,

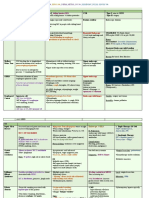

Table 1. Patients age groups prevalence

gastrointestinal haemorrhage and constipation in

n=756.

one (0.1%) for each. The non-specific abdominal

Age group Prevalence of age groups

pain topped the list in the youngest age group of

15-19 44 (5.8%) 15-19 occurring in 42 out of 44 (95.5%) while

20-39 277 (36.6%) abdominal distension was mostly seen in 10

40-59 216 (28.6%) (40%) out of the 25 over 80 patients. Haematuria

affected 8 (2.9%) of the 277 patients aged 20-39.

60-79 194 (25.7%)

Abdominal pain was the commoner presentation

80-100 25 (3.3%) in 335 (93.2%) of females compared to 324

(86.4%) in males. PAR's were the only imaging

Table 2. Indications for plain abdominal test for the vast majority of cases 594 (78.57%).

radiographs (PARS) request n=756. In 103 (13.6%) conventional contrasted CT was

Non-Specific Abdominal pain 516 (68.2%)

requested. In 33 (4.3%) LDCT was added. None

had U-LDCT as it was not available. US was

Organ specific abdominal pain 77 (10.1%)

used in 52 (6.8%) and MRI for only one patient

Abdominal distension 69 (9.1%)

(0.1%). TABLE 3 demonstrates the average of

Vomiting 29 (3.8%)

1.25 scans added per patient. The sensitivity

Urinary tract symptoms 23 (3.0%)

and specificity of PARS and CT are reported in

Intestinal obstruction 22 (2.9%)

(TABLES 4 and 5) with the discharge diagnosis

Perforation 4 (0.5%)

as the gold standard. When both PARS and

Mass 2 (2.6%)

CT were used, there was a congruence of only

FB 2 (2.6%)

35.5% for diseased cases (Kappa SE 0.044) (5%

Constipation 1 (0.1%)

confidence interval -0.152-0.239).

Ischaemia 1 (0.1%)

GI bleed 1 (0.1%) The final diagnosis was considered the gold

Incomplete records 9 (1.2%) standard and taken from the ED or the in-

patient discharge summary. Renal stones were

Table 3. Number of performed radiologic commoner in males than females, while UTI

tests for those who had PAR’s n=756. inflammatory bowel disease and cholelithiasis

Number of performed tests Number of patients were commoners in women (TABLE 6).

PAR’s alone 1 test 594 (78.57%) Urolithiasis was commoner in the 50-59 and the

PAR’s plus one tests 2 tests 140 (18.51%) 20-39 age groups but not detected in the young

PAR’s plus 2 tests 3 tests 17 (2.35%) 15-19 group. There was no case of diverticulitis

PAR’s plus 3 tests 4 tests 2 (0.53%) or foreign body in this series. Intestinal

Incomplete records ------- 3 (0.39%) obstruction and severe constipation were both

Table 4. Comparison of our PAR’s Sensitivity and Specificity for intestinal obstruction and

urinary stones.

Diagnosis Sensitivity (95% CI) Specificity (95% CI) PPV (95% CI) NPV (95% CI)

Intestinal obstruction 50 99.06 41.6 99.33

Urinary stones 32.8 99.56 88 93.84

Table 5. Sensitivity and specificity of CT for intestinal obstruction and urinary stones.

Sensitivity(95%CI) Specificity (95% CI) PPV (95% CI) NPV (95% CI)

Intestinal obstruction 83.33 96.91 62.50 98.95

Renal stones 91.3 97.50 91.30 97.50

Imaging Med. (2017) 9(6) 181

RESEARCH PAPER El Bagi MA, Mutairi B, Alsolamy S, Alaizari M, Alrasheed S, et al.

Table 6. Comparison of the commonest final diagnosis across gender n=756.

Diagnosis Females n=381 Males n=375

Renal stones 25 (6.6%) 42 (11.2%)

Cholelithiasis 21 (5.5%) 9 (2.4%)

Intestinal obstruction 3 (0.8%) 7 (1.9%)

Inflammatory bowel disease 8 (2.1%) 3 (0.85)

Appendicitis 2 (0.5%0 9 (2.4%)

UTI 75 (19.7%) 43 (11.5%)

Pancreatitis 2 (0.5%) 5 (1.3%)

Table 7. Common final diagnosis distribution across age categories n=756.

Diagnosis 15-19 years 20-39 years 40-59 years 60-79 years 80-100 years

Renal stones -- 30 (10.9%) 25 (11.6%) 11 (5.7%) 1 (4%)

Appendicitis 1 (2.3%) 6 (2.2%) 3 (1.4%) 1 (0.5%) --

Pancreatitis -- 1 (0.4%) 2 (0.9%) 5 (2.6%) --

Intestinal Obstruction -- 2 (0.7%) 1 (0.5%) 6 (3.1%) 1 (4%)

Cholelithiasis -- 6 (2.2%) 11 (5.1%) 12 (6.2%) 1 (4%)

UTI 7 (15.9%) 47 (17%) 28 (13%) 35 (18%) 1 (4%)

Gastroenteritis 8 (18.2%) 24 (8.7%) 18 (8.3%) 8 (4.1%) --

commoners in the 60-79 age group while The non-specific abdominal pain was the

gastroenteritis was commoner in the young age most frequent clinical presentation similar to a

group of 15-19.UTI was least frequent in the previous report of 22 different studies involving

80-100 years group (TABLE 7). 3340 patients [19]. However, the second

The most frequent finding on CT was renal commonest in this series were renal problems

stones in 23 (22.33%) of the 103 patients in 185 (24.4%) whereas it was appendicitis

scanned. Appendicitis was detected in 5 in other series of 3340 patients [19]. This

(4.85) Intestinal obstruction in 8 (7.77%) and difference indicates a geographic variation of

pancreatitis disease patterns as suggested previously [8].

Gastroenteritis was prominent in this study 58

3 (2.91%) of those who had CT. None of the (8%), affecting 8 (18.2%) of the youngest age

severely constipated patients underwent a CT group of (15-19 years). This is perhaps due to

scan. CT was normal in 10 (9.71%) of the 103 the current trend in young people to consume

referred for scanning after PAR’s. fast food from food trucks. The sensitivity and

specificity of PAR’s for intestinal obstruction

Discussion

was 50% and 99.6% (TABLE 4). This result

The results of this study show that PAR’s

matched with a published literature of 49 % and

were surprisingly commonly used alone for the

98%, respectively [18]. The 32.8% sensitivity

majority of cases. This finding contradicts the

and 99.65% specificity of PAR’s for urinary

previous beliefs that the expatriate staffs in this

stones were higher than previous reports of 9%

affluent country are overusing other imaging

and 99% respectively. The 91.35%sensitivity and

modalities as a self-protective attitude [22]. 97.5% specificity of CT for renal calculi were

PAR’s alone, were requested for the majority higher in this series compared to earlier reports

of cases 594 (78.57%) unlike the previous of 68% sensitivity and 91% specificity [18].

report of 21% [2]. In that paper, CT or US were The higher prevalence and higher sensitivity

used for 42% of cases compared to 24.7% in of urolithiasis in this series are due to the dry

this series. This finding was not explained in this climate effect of dehydration and the stone's

study and possibly due to strict compliance with chemistry. CT sensitivity of 83.3% for intestinal

departmental policies. Another possibility is the obstruction was higher than the previous report

increased demand for CT at this tertiary trauma of 75%, but the 96.91% specificity was lower

referral centre, and the staff tendency to reserve than the 99% specificity of the previous report

CT for the needier and polytrauma patients. (TABLE 5). PAR’s low sensitivity for intestinal

obstruction of 50% in this series matched

182 Imaging Med. (2017) 9(6)

Should plain radiographs persist or be replaced by alternative scans for imaging of

acute painful non-traumatic abdominal pain?

RESEARCH PAPER

previous reports 0f 49% [18]. Specificity of nature. The severity of pain was not scored.

PAR’s and CT for intestinal obstruction was Patients were not followed up beyond the

high at 99 and 98%, respectively [18]. discharge time. The age groups were not stratified

for disease prevalence. The appropriateness of

Surprisingly US were, however, less utilized

those who underwent PAR’s was not reviewed.

than CT in this series. The recent ED 4 h

LDCT sensitivity was not assessed separately

clearance target restriction has limited the time

from conventional CT. Numbers of either scan

for US referral to the radiology department

were small for accurate judgment. Patients who

which is at a distance from ED while PAR’s are

presented with ANTAP and sent directly to US

available within the ED. MRI was only used

or CT initially were not included even if they

once despite recent reports of usefulness [22].

subsequently underwent PAR’s. This exclusion

PAR’s have the advantage of delivering less than could explain the rarity of known common

one-fifth of the standard contrasted CT dose which conditions like appendicitis in this report which

has favoured its use as a first line test. It was however would have been directly sent for either a CT

of much lower sensitivity compared to CT in this or US scan.

series and by other researchers in (TABLES 4 and

5) [18]. When both PAR’s and conventional CT Conclusion

were used, there was an unsatisfactory congruence The results of this study indicate that PAR’s

of PAR’s with CT in 35.7% for the significantly are still a one-stop shop imaging test when

abnormal cases. This observation should favour the requested by the ED for ANTAP despite the

use of CT as the first test albeit higher radiation availability of CT, US and MRI. The 4 h target

dose. There was however little utilization of LDCT at the ED limits the number of imaging tests

in 33 (4.3%) of cases. The radiation dose of LDCT that can be performed. PAR’s accuracy finding

stone protocol for 40 consecutive patients in 4 in this series matched other workers except for

different CT scanners was reviewed. The average higher sensitivity for urolithiasis. In patients

dose was 4.898- 5.257 mSv, less than half the who had both CT and PAR’s, there was an

conventional CT dose but still higher than the unsatisfactory congruence of findings due to

dose deliverable by PAR’s. the lower sensitivity of PAR’s. There is a need

Study limitations to replace the insensitive PAR’s and avoid the

higher radiation dose of conventional CT by

The limitation of this study is the retrospective

alternative tests.

251 (2005). low-dose, and standard-dose CT of the kidney,

REFERENCES ureters, and bladder: is there a difference? Results

1. Cartwright S, Knudson MP. Diagnostic imaging 8. Me Collough C, Primak A, Braun N, et al.

from a systematic review of the literature. Clin.

of acute abdominal pain in adults. Am. Fam. Strategies for reducing radiation dose in CT.

Radiol. 72, 11-15 (2017).

Physician. 91, 452-459 (2015). Radiol. Clin. North. Am. 74, 27-40 (2009).

14. 14.Kellow ZS, MacInnes M, Kurzencwyg D,

2. Gans S, Stoker J, Boermeester M. Abdominal 9. Mathews J, Forsythe A, Brady Z, et al. Cancer

et al. The role of abdominal radiography in

radiography in acute abdominal pain. Inter. J. risk in 680000 people exposed to computed

the evaluation of the non-trauma emergency

Gen. Med. 5, 525-533 (2012). tomography scan in childhood or adolescence.

patient. Radiol. 284, 887-893 (2008).

Data linkage study of 11 million Australians.

3. Van RA, Lameris W, Wouter H, et al. A BMJ. 346, 2360 (2013). 15. Ahn SH, Mayo SWW, Murphy BL, et al. Acute

comparison of the accuracy of ultrasound and nontraumatic abdominal pain in adult patients:

computed tomography in common diagnoses 10. Nguyen L, Wong D, Fatovich D, et al. Low dose

abdominal radiography compared with CT

causing acute abdominal pain. Eur. Radiol. 21, computed tomography versus plain radiograph

evaluation. Radiol. 225, 159-64 (2002).

1535-1545 (2011). in the investigation of acute abdomen. AZN. J.

Surg. 82, 36-41 (2012). 16. Lameris W, Randen VA, Van EHW, et al.

4. Fields S. Plain films: The acute abdomen. Clin. Imaging strategies for detection of urgent

Gastroenterol. 13, 3-40 (1984). 11. Haller O, Karlsson L, Nyman R. Can low dose

conditions in patients with acute abdominal

abdominal CT replace plain abdominal film in

5. Smith J, Hall. The use of abdominal X-rays in pain: diagnostic accuracy study. BMJ. 338, 2431

an evaluation of acute abdominal pain? Ups. J.

the emergency department. Emerg. Med. J. 26, (2009).

Med. Sci. 115, 113-120 (2010).

160-163 (2009). 17. Hastings RS. Powers RD: Abdominal pain in

12. Pickhardt PJ, Lubner MG, Kim DH, et al.

6. Brewer BJ, Golden GT, Hitch DC, et al. the ED: a 35-year retrospective. Am. J. Emerg.

Abdominal CT with model-based iterative

Abdominal pain. An analysis of 1000 consecutive Med. 29, 711–716 (2011).

reconstruction (MBIR): initial results of a

cases in a university hospital emergency room. prospective trial comparing ultra-low dose with 18. Stoker J, Van Randen, Meris LW, et al. Imaging

Am. J. Surg. 131, 219-213 (1976) . standard-dose imaging. AJR. Am. J. Roentgenol. patients with Acute Abdominal Pain. Radiol.

7. Prasanna S, Zhang TJ, Gul YA. Diagnostic value 199, 1266-1274 (2012). 353, 31-46 (2009).

of main abdominal radiographs in patients with 13. Rob S, Bryant T, Wilson I, et al. Ultra-low-dose, 19. Remedios D, McCoubrie P. Making the best

acute abdominal pain. Asian. J. Surg. 28, 245-

Imaging Med. (2017) 9(6) 183

RESEARCH PAPER El Bagi MA, Mutairi B, Alsolamy S, Alaizari M, Alrasheed S, et al.

use of clinical radiology Services. Referral abdominal pain. Dig. Surg. 32, 23-31 (2015). 22. Singh A, Danrad R, Hahn P, et al. MR Imaging

Guidelines .Clin. Radiol . 62, 919-920 (2007). of the Acute Abdomen and Pelvis: Acute

21. Abd El Bagi, Damegh S, Linjawi T. Unnecessary

Appendicitis and Beyond. Radiographics.27,

20. Gans SL, Pols MA, Stoker J, et al. Guidelines X-rays. Occurrence, Disadvantages and Side

1419-1431 (2007).

for the diagnostic pathway in patients with acute Effects. Saudi. Med. J. 20, 491-494 (1999).

184 Imaging Med. (2017) 9(6)

You might also like

- Successful Retrieval of A Dislodged Zotarolimuseluting Coronary Stent in The Ascending AortaDocument3 pagesSuccessful Retrieval of A Dislodged Zotarolimuseluting Coronary Stent in The Ascending AortaShira michaelNo ratings yet

- A Multiparametric Mri Score For Prostate Cancer Detection Performance in Patients With and Without Endorectal CoilDocument8 pagesA Multiparametric Mri Score For Prostate Cancer Detection Performance in Patients With and Without Endorectal CoilShira michaelNo ratings yet

- Interference With Creatinine Estimation by Impenem Cilastatin in Jaffes Kinetic MethodDocument2 pagesInterference With Creatinine Estimation by Impenem Cilastatin in Jaffes Kinetic MethodShira michaelNo ratings yet

- Highintensity Focused Ultrasound of Uterine Fibroids and Adenomyosis Maneuver Technique For BowelDocument3 pagesHighintensity Focused Ultrasound of Uterine Fibroids and Adenomyosis Maneuver Technique For BowelShira michaelNo ratings yet

- Cd146 Expression As A Surrogate Biomarker For Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Multilineage Differentiation Is Preserved DDocument13 pagesCd146 Expression As A Surrogate Biomarker For Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Multilineage Differentiation Is Preserved DShira michaelNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Endotracheal Cuff Pressure Measurements Before and After Nursing Care in Emergency Patients Pilot BalloonDocument5 pagesComparison of Endotracheal Cuff Pressure Measurements Before and After Nursing Care in Emergency Patients Pilot BalloonShira michaelNo ratings yet

- The Role of History of Disease Factors in The Congenital Heart Disease in AdultsDocument4 pagesThe Role of History of Disease Factors in The Congenital Heart Disease in AdultsShira michaelNo ratings yet

- Rheumatology To Hepatology Cross Talk An Evidence Based Update On The Treat To Target Strategy in Hepatitisc Related ExtDocument9 pagesRheumatology To Hepatology Cross Talk An Evidence Based Update On The Treat To Target Strategy in Hepatitisc Related ExtShira michaelNo ratings yet

- Respiratory Function Following Onpump Versus Offpump Coronary Bypass Grafting SurgeryDocument7 pagesRespiratory Function Following Onpump Versus Offpump Coronary Bypass Grafting SurgeryShira michaelNo ratings yet

- A Clinical Study of Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Younger and Elder Rectal Cancer PatientsaDocument12 pagesA Clinical Study of Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Younger and Elder Rectal Cancer PatientsaShira michaelNo ratings yet

- Yatri R. Shah, Dhrubo Jyoti Sen and C N Patel - Schiff's Bases of Piperidone Derivative As Microbial Growth InhibitorsDocument9 pagesYatri R. Shah, Dhrubo Jyoti Sen and C N Patel - Schiff's Bases of Piperidone Derivative As Microbial Growth InhibitorsSmokeysamNo ratings yet

- Effects of Exenatide On Both Fat Mass Loss and Cardiometabolic Risk in Obese Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes MellitusDocument7 pagesEffects of Exenatide On Both Fat Mass Loss and Cardiometabolic Risk in Obese Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes MellitusShira michaelNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Rigid and Deformable Image Registration Accuracy of The Liver During Longterm Transition After Proton BeamDocument6 pagesComparison of Rigid and Deformable Image Registration Accuracy of The Liver During Longterm Transition After Proton BeamShira michaelNo ratings yet

- Onset Patterns of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Myalgic EncephalomyelitisDocument30 pagesOnset Patterns of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Myalgic EncephalomyelitisShira michaelNo ratings yet

- Highintensity Focused Ultrasound of Uterine Fibroids and Adenomyosis Maneuver Technique For BowelDocument3 pagesHighintensity Focused Ultrasound of Uterine Fibroids and Adenomyosis Maneuver Technique For BowelShira michaelNo ratings yet

- Successful Retrieval of A Dislodged Zotarolimuseluting Coronary Stent in The Ascending AortaDocument3 pagesSuccessful Retrieval of A Dislodged Zotarolimuseluting Coronary Stent in The Ascending AortaShira michaelNo ratings yet

- Quantitative Analysis On Literature of Working Memory On The Athlete in ChinaDocument5 pagesQuantitative Analysis On Literature of Working Memory On The Athlete in ChinaShira michaelNo ratings yet

- Phytochemical and Antimicrobial Studies of Oroxylum Indicum ExtractsDocument8 pagesPhytochemical and Antimicrobial Studies of Oroxylum Indicum ExtractsShira michaelNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Endotracheal Cuff Pressure Measurements Before and After Nursing Care in Emergency Patients Pilot BalloonDocument5 pagesComparison of Endotracheal Cuff Pressure Measurements Before and After Nursing Care in Emergency Patients Pilot BalloonShira michaelNo ratings yet

- A Rare Complication of Acute Cholecystitis Leading To Perihepatic Abscess Gall Bladder PerforationDocument3 pagesA Rare Complication of Acute Cholecystitis Leading To Perihepatic Abscess Gall Bladder PerforationShira michaelNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Intestinal Obstruction: Zeeshan Razzaq MRCS Ire, MRCS Ed, MRCS Eng Colorectal RegistrarDocument61 pagesIntestinal Obstruction: Zeeshan Razzaq MRCS Ire, MRCS Ed, MRCS Eng Colorectal Registraraini natashaNo ratings yet

- Interpretasi Foto AbdomenDocument96 pagesInterpretasi Foto AbdomenGaluh EkaNo ratings yet

- An Unusual Cause of Small Bowel Obstruction: Internal Supravesical HerniaDocument4 pagesAn Unusual Cause of Small Bowel Obstruction: Internal Supravesical HerniaIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Acute Abdominal Pain MS LectureDocument63 pagesAcute Abdominal Pain MS LectureRovanNo ratings yet

- Abdominal Pain: LSU Medical Student Clerkship, New Orleans, LADocument48 pagesAbdominal Pain: LSU Medical Student Clerkship, New Orleans, LALeonardo Adi BestNo ratings yet

- Acute Abdomen: The "Black Hole" of MedicineDocument97 pagesAcute Abdomen: The "Black Hole" of Medicineedward iskandarNo ratings yet

- NASPGHAN Capsule Endoscopy Clinical Report.28Document10 pagesNASPGHAN Capsule Endoscopy Clinical Report.28Carlos CuadrosNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan On Intestinal ObstructionDocument41 pagesLesson Plan On Intestinal ObstructionLoma Waghmare (Jadhav)100% (1)

- I Am An Exam Question: Pre-Operative Physical Examination of A Surgical PatientDocument9 pagesI Am An Exam Question: Pre-Operative Physical Examination of A Surgical PatientMyrtle Yvonne RagubNo ratings yet

- Weaning from Parenteral Nutrition: Strategies and ConsiderationsDocument26 pagesWeaning from Parenteral Nutrition: Strategies and ConsiderationsJosebeth RisquezNo ratings yet

- IntussusceptionDocument10 pagesIntussusceptionshenlie100% (1)

- History Taking in Medicine and Surgery: Third EditionDocument48 pagesHistory Taking in Medicine and Surgery: Third EditionSapreni agustinaNo ratings yet

- GastroenterologyDocument8 pagesGastroenterologyRumana AliNo ratings yet

- Surgical Ho Guide PDFDocument76 pagesSurgical Ho Guide PDFMardiana KamalNo ratings yet

- Pediatrics Acute AbdomenDocument67 pagesPediatrics Acute AbdomenCabdi IshakNo ratings yet

- Approach To The Adult With Nausea and Vomiting - UpToDateDocument20 pagesApproach To The Adult With Nausea and Vomiting - UpToDateJolien JobsNo ratings yet

- ULCERATIVE COLITIS-doneDocument6 pagesULCERATIVE COLITIS-donecory kurdapyaNo ratings yet

- Intestinal ObstructionDocument9 pagesIntestinal ObstructionHamss AhmedNo ratings yet

- 3 Year CPC October 8, 20202Document4 pages3 Year CPC October 8, 20202Raian SuyuNo ratings yet

- DR Wifanto S Jeo, SPB-BD - Acute AbdomenDocument28 pagesDR Wifanto S Jeo, SPB-BD - Acute AbdomenIrma DamayantiNo ratings yet

- Gastrointestinal Manifestations of HIV Http-::hivinsite - Ucsf.eduDocument21 pagesGastrointestinal Manifestations of HIV Http-::hivinsite - Ucsf.edufitriNo ratings yet

- Appendicitis and PeritonitisDocument22 pagesAppendicitis and PeritonitisElizar JarNo ratings yet

- Surgery EORDocument76 pagesSurgery EORAndrew BowmanNo ratings yet

- Radiology Notes by Zainab MamDocument88 pagesRadiology Notes by Zainab MamBiveshta SharmaNo ratings yet

- POZE Professor - Dr. - Dieter - Beyer, - Professor - Dr. - Ulrich - (B-Ok - CC) PDFDocument463 pagesPOZE Professor - Dr. - Dieter - Beyer, - Professor - Dr. - Ulrich - (B-Ok - CC) PDFUffie-Isabela GheNo ratings yet

- GastroparesisDocument31 pagesGastroparesisGaby ZuritaNo ratings yet

- Infantile Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis - UpToDateDocument22 pagesInfantile Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis - UpToDateNELFA MOLINA DUBÓNNo ratings yet

- Abdominal Tuberculosis: Prof. M.P. SharmaDocument38 pagesAbdominal Tuberculosis: Prof. M.P. SharmaFarhana Yasmin MouryNo ratings yet

- Causes of Abdominal Pain in Adults - UpToDateDocument13 pagesCauses of Abdominal Pain in Adults - UpToDateAudricNo ratings yet

- Department of Surgery: Case Presentation Intestinal ObstructionDocument46 pagesDepartment of Surgery: Case Presentation Intestinal Obstructionhadil ayeshNo ratings yet