Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Rovee Collier1999 Memory

Uploaded by

antegeia2222Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Rovee Collier1999 Memory

Uploaded by

antegeia2222Copyright:

Available Formats

80 VOLUME 8, NUMBER 3, JUNE 1999

dergo over the first 18 months of

The Development of Infant Memory life (see Fig. 1). Unfortunately, even

Carolyn Rovee-Collier1 when the same task was used, re-

searchers often changed stimuli

Department of Psychology, Rutgers—The State University of New Jersey, and task parameters nonsystemati-

Piscataway, New Jersey

cally; failed to equate age differ-

ences in motivation, stimulus

possess only a primitive memory salience, task demands, or original

Abstract learning; or used identical instruc-

system that cannot encode specific

Over the first year and a half tions or prompts with infants who

events (Mandler, 1998), that early

of life, the duration of memory differed in verbal competence.

development is characterized by

becomes progressively longer, Such practices made cross-age

“infantile amnesia” (the absence of

the specificity of the cues re- comparisons precarious at best.

quired for recognition progres- enduring memories; Pillemer &

To sidestep these problems, my

sively decreases after short test White, 1989), that children cannot

colleagues and I have used two

delays, and the latency of remember events until they can re-

nonverbal tasks to study infants’

priming progressively decreas- hearse them by talking about them

memory development—a mobile

es to the adult level. The mem- (Nelson, 1990), and that children

task with 2- to 6-month-olds and a

ory dissociations of very younger than 18 months are inca-

train task with 6- to 18-month-olds.

young infants on recognition pable of representation (Piaget,

All task parameters are standard-

and priming tasks, which pre- 1952); others argue that the behav-

ized and age-calibrated. Because

sumably tap different memory ior of older infants and children is

the memory performance of 6-

systems, are also identical to shaped by their earlier experiences

month-olds is identical on these

those of adults. These parallels (Watson, 1930) and that adult per-

two tasks, comparisons between

suggest that both memory sys- sonality is shaped by memories of the memory performance of older

tems are present very early in events that occurred in infancy and younger infants is not con-

development instead of (Freud, 1935). Surprisingly, this de- founded by the shift in task.

emerging hierarchically over bate has been waged in the absence In the mobile task, infants learn

the 1st year, as previously of data from infants themselves. to move a crib mobile by kicking

thought. Finally, even young This article reviews new evi- via a ribbon strung between the

infants can remember an event dence that infants’ memory pro- mobile hook and one ankle (see

over the entire “infantile am- cessing does not fundamentally Fig. 2a). The rate at which they ini-

nesia” period if they are peri- differ from that of older children tially kick before the ankle ribbon is

odically exposed to appropri- and adults. Not only can older chil- connected to the mobile serves as a

ate nonverbal reminders. In dren remember an event that oc- baseline for comparison with their

short, the same fundamental curred before they could talk, but kick rate during the subsequent

mechanisms appear to under- even very young infants can re- recognition test, when infants are

lie memory processing in in- member an event over the entire in- again placed under the mobile

fants and adults. fantile-amnesia period if they are while the ankle ribbon is discon-

periodically reminded. nected. If they recognize the mobile

Keywords (see Fig. 2b), they kick above their

recognition; priming; infantile baseline rate; otherwise, they do

amnesia; reminders DEVELOPMENTAL

not. In the train task, infants learn

CHANGES IN

to move a miniature train around a

RECOGNITION

circular track by depressing a lever

All people have a natural curios- (see Fig. 3). Again, baseline is mea-

ity about their own memory. This Before now, the major impedi- sured, and retention is tested when

curiosity was tweaked several ment to research on infants’ memo- the lever is deactivated; infants

years ago by reports in the popular ry development was methodologi- who recognize the train respond

press of recovered memories from cal: Tasks commonly used with above their baseline rate.

early childhood. These reports also older infants were inappropriate Infants ages 2 to 18 months have

renewed a long-standing debate for younger ones. This problem is been identically trained for 2 suc-

about whether infants can actually not surprising when one considers cessive days in the mobile or train

remember for any length of time. the considerable physical and be- task and tested after a series of dif-

Some researchers argue that infants havioral changes that infants un- ferent delays. They exhibit equiva-

Published by Blackwell Publishers, Inc.

CURRENT DIRECTIONS IN PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE 81

lent retention after short delays,

but their duration of retention in-

creases linearly with age (see Fig.

4)—a result not attributable to age

differences in activity or speed of

learning. At any given age, howev-

er, memory performance can be al-

tered simply by changing the pa-

rameters of training. If given three

6-min training sessions instead of

two 9-min sessions, for example, 8-

week-olds remember for 2 weeks

(as long as 6-month-olds given two

6-min sessions), instead of 1 or 2

days only.

Age differences in retention that

have been obtained with other

paradigms similarly reflect differ-

ences in task parameters and not

in the underlying memory

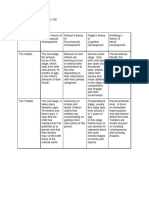

Fig. 1. Infants 2, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18 months of age (from left to right). Note the dra- processes. In the deferred-imita-

matic differences between the younger and older infants. tion paradigm, for example, in-

fants watch an adult manipulate

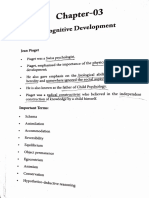

a b

Fig. 2. A 3-month-old during training in the mobile task and during a retention test. During training (a), the infant’s kicks move

the mobile by means of the ankle ribbon that is connected to the mobile hook. During baseline and all retention tests (b), the ankle

ribbon and the mobile are connected to different hooks so that kicks cannot move the mobile.

Copyright © 1999 American Psychological Society

82 VOLUME 8, NUMBER 3, JUNE 1999

that novel objects can cue retrieval

only after delays when they can be

clearly differentiated from the orig-

inal training objects indicates that

older infants actively disregard the

difference. This emerging strategy

enables older infants to “test the

waters” and determine whether or

not new objects that they encounter

in the same context are functionally

equivalent to the old ones.

When the training and testing

contexts differ, infants exhibit a dif-

ferent pattern. At 3, 9, and 12

months of age, infants recognize

the training object in a different

context after all but the very

longest test delays. Apparently,

when the memory is weak, infor-

mation about the context facilitates

Fig. 3. A 6-month-old infant during training in the train task. Pressing the lever

moves the toy train. its retrieval. Between 12 and 24

months of age, infants will also im-

an object and are asked to imitate train or in a context different from itate an action that they saw in one

those actions later. At 6 months where they were trained. Because context (e.g., the day-care center)

(the youngest age at which this infants remember increasingly when tested with the same object in

paradigm can be used), infants longer as they get older (see Fig. 4), a different context (e.g., the labora-

who watch for 30 s in a single ses- we compared their memory per- tory) a few days later. Taken to-

sion successfully imitate if tested formance after equivalent delays— gether, these findings reveal that

immediately afterward, but not if the shortest, middle, and longest infants can remember what they

tested 24 hr later; if they watch for points on the forgetting function of learn in one place if tested in an-

60 s, however, they can imitate each age. other except after relatively long

successfully 24 hr later (Barr, For infants between 2 and 6 delays. Parents, educators, and

Dowden, & Hayne, 1996). months of age, only the original public policy experts will be com-

Similarly, 18-month-olds exhibit mobile (or train) is an effective re- forted to know that infants can

deferred imitation for 4 weeks trieval cue when testing occurs 1 transfer what they learn at the day-

after one session but for 10 weeks day after training; a novel one is care center or in nursery school to

after two sessions. not. For infants between 9 and 12 home if given an opportunity to do

so before too much time has

months of age, however, a novel

passed.

train can cue retrieval when testing

DEVELOPMENTAL occurs within 2 weeks of training,

CHANGES IN MEMORY but not after longer delays (from 3

SPECIFICITY to 8 weeks), when only the original DEVELOPMENTAL

train can cue retrieval. A similar CHANGES IN PRIMING

pattern is seen in deferred-imita- LATENCY

Because only cues that are high-

ly similar to what is in a memory tion tests, although the duration of

can retrieve it, the informational retention in this paradigm is short- Even if infants cannot recognize

content of infants’ memories can be er overall. Six-month-olds will not a stimulus, like adults, they can still

determined by probing the memo- imitate if the test object is novel. respond to it if they are exposed to

ries with different retrieval cues Twelve-month-olds will—but only a memory prime (or prompt) be-

and seeing which ones are effec- after delays on the order of min- fore the retention test. The prime,

tive. We followed this strategy with utes; after longer delays, they will an isolated component of the origi-

infants from 2 to 12 months of age imitate only if the test object is the nal training situation, such as the

by testing them after a series of de- one they saw originally (Hayne, original mobile or context, initiates

lays either with a new mobile or MacDonald, & Barr, 1997). The fact a perceptual identification process

Published by Blackwell Publishers, Inc.

CURRENT DIRECTIONS IN PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE 83

Fig. 5. Decrease in priming latency

(graphed in log seconds) over the 1st

year of life. Open circles show results

on the mobile task, and filled circles

show results on the train task; 6-month-

olds were trained, primed, and tested

in both tasks. Each data point indicates

how long it took infants of a given age

to exhibit retention after being exposed

to a 2-min prime.

DEVELOPMENT OF

MULTIPLE MEMORY

SYSTEMS

Fig. 4. Maximum duration of retention over the first 18 months of life. Filled circles

show retention on the mobile task, and open circles show retention on the train task;

6-month-olds were trained and tested in both tasks. The notion that memory pro-

cessing is mediated by two func-

tionally different and independent

that facilitates retrieval of the latent months of age, infants responded memory systems originated more

memory by increasing its accessi- instantaneously to the prime (see than a quarter-century ago with

bility. In a recent series of studies, Fig. 5). clinical observations that amnesics

Hildreth and I primed memories This result reveals that the are impaired relative to normal

that infants had forgotten (i.e., their speed of memory processing in- adults on recognition but not on

performance on the long-term re- creases over the 1st year of life. priming tests. Amnesics, for exam-

tention test was at baseline) and Even at 3 months of age, however, ple, performed poorly when asked

then assessed how long it took for infants respond instantaneously if to recognize which of four words

the memories to be recovered (i.e., a prime is presented if the memo- was on a list they had studied just

for infants to exhibit significant re- ry was recently acquired. Infants minutes earlier, but they performed

tention on the ensuing test; who were trained with a three- as well as normal adults when

Hildreth & Rovee-Collier, 1999). mobile serial list, for example, rec- given a word fragment (the prime)

Infants from 3 to 12 months of age ognized only the first mobile on and asked to complete it with the

were trained in the mobile or train the list 24 hr later—a classic pri- first word that came to mind.

task and were primed—only macy effect. If primed with the Typically, they completed the word

briefly and only once—with the first mobile immediately before fragments with words from the

original mobile or train 1 week the 24-hr test, however, they also previous study list, even though

after they no longer recognized it. recognized the second mobile; and they could not recognize them.

Even though the time it took in- if successively primed with the This dissociation suggested that

fants to forget the training event in- first two mobiles on the study list, recognition and priming tests tap

creased linearly with age (see Fig. they recognized the third mobile different underlying memory sys-

4), the latency of priming decreased (Gulya, Rovee-Collier, Galluccio, tems—one that is impaired in am-

over this same period until, at 12 & Wilk, 1998). nesia (explicit or declarative mem-

Copyright © 1999 American Psychological Society

84 VOLUME 8, NUMBER 3, JUNE 1999

ory) and one that is not (implicit or that periodic nonverbal reminders In the second study (Hartshorn,

nondeclarative memory). Since can maintain the memory of an 1998), 6-month-olds learned the

then, more than a dozen independ- event from early infancy (2 and 6 train task, were briefly reminded at

ent variables have been found to months of age) through 1 1/2 to 2 7, 8, 9, and 12 months of age, and

differentially affect adults’ memory years of age—-the entire span of were tested at 18 months of age.

performance on recognition and the developmental period thought Although 6-month-olds typically

priming tests, and memory dissoci- to be characterized by infantile forget after 2 weeks, after being pe-

ations have become a diagnostic for amnesia. In the first study (Rovee- riodically reminded, they still ex-

the existence of two memory Collier, Hartshorn, & DiRubbo, in hibited significant retention 1 year

systems. press), 8-week-olds learned the later, at 18 months of age. In addi-

For years, these memory sys- mobile task. Every 3 weeks there- tion, 5 of 6 infants who were re-

tems were thought to develop hier- after until infants were 26 weeks minded immediately after the 18-

archically, with infants possessing of age, they received a preliminary month test still remembered when

only the primitive, perceptual- retention test followed by a 3-min retested at 24 months of age, 1 1/2

priming system until late in their visual reminder—either a reacti- years after the original event. These

1st year. This assumption was vation (priming) treatment in infants had encountered only one

based on the Jacksonian “first in, which they merely observed a mo- reminder (at 18 months) in the pre-

last out” principle of the develop- bile moving (a nonmoving mobile ceding year!

ment and dissolution of function is not an effective reminder) or a Unfortunately, the mobile task is

(i.e., the function that appears earli- reinstatement treatment in which inappropriate for infants older than

est in development disappears last they moved it themselves by kick- 6 months, and the train task is in-

when the organism is undergoing ing. Their final retention test oc- appropriate for infants younger

demise), but empirical support for than 6 months. However, because

curred at 29 weeks of age, when

it in the domain of memory came periodic nonverbal reminders

the experiment had to be termi-

only from studies of aging am- maintained memories of these two

nated because the infants outgrew

nesics (McKee & Squire, 1993)—not comparable events over an over-

the task. Although 8-week-olds

infants. Now, new evidence has lapping period between 2 months

forget after 1 to 2 days (see Fig. 4),

shown that all of the same inde- and 2 years of age, it seems highly

after exposure to periodic re-

pendent variables that produce dis- likely that periodic nonverbal re-

minders, they still exhibited sig-

sociations on recognition and prim- minders could also maintain the

nificant retention 4 1/2 months

ing tests with adults produce memory of a single event from 2

dissociations on recognition and later, and most still remembered 5

months through 2 years of age, if

priming tests with infants as well 1/4 months later. Control infants

not longer.

(Rovee-Collier, 1997). For example, who were not trained originally

priming produces the same degree but saw the same reminders as

of retention after all training-test their experimental counterparts WHENCEFORTH INFANTILE

delays, but the degree of retention exhibited no retention after any AMNESIA?

on recognition tests decreases as delay.

the training-test delay becomes The impact of periodic re-

minders is illustrated in Figure 6, The preceding evidence raises

longer for both adults (Tulving,

which shows the retention data of serious doubts about the generality

Schacter, & Stark, 1982) and infants.

individual 8-week-olds superim- of infantile amnesia, as well as the

This evidence demonstrates that

posed on the retention function accounts that have been put forth

the Jacksonian principle does not

apply to the development of mem- from Figure 4. When the experi- to explain it. Clearly, neither the

ory systems; rather, both systems ment ended, four 8-week-olds had immaturity of their brain nor their

are present and functional from remembered as long as expected of inability to talk limits how long

early infancy. 2 1/4-year-olds, one had remem- young infants can remember an

bered as long as expected of 2-year- event. As long as they periodically

olds, and the infant with the “poor- encounter appropriate nonverbal

est” memory had remembered for reminders, their memory of an

MAINTAINING MEMORIES

as long as children almost 1 1/2 event can be maintained—perhaps

WITH REMINDERS

years old. Had we been able to con- forever. Because a match between

tinue the study, some infants un- the encoding and retrieval contexts

Two recent studies from our doubtedly would have remem- is critical for retrieval after very

laboratory have demonstrated bered even longer. long delays, however, a shift from

Published by Blackwell Publishers, Inc.

CURRENT DIRECTIONS IN PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE 85

Acknowledgments—This research was

supported by Grants R37-MH32307 and

K05-MH00902 from the National

Institute of Mental Health.

Note

1. Address correspondence to

Carolyn Rovee-Collier, Department of

Psychology, Rutgers University, 152

Frelinghuysen Rd., Piscataway, NJ

08854-8020; e-mail: rovee@rci.rutgers.

edu.

References

Barr, R., Dowden, A., & Hayne, H. (1996).

Developmental changes in deferred imitation

by 6- to 24-month-old infants. Infant Behavior

and Development, 19, 159–170.

Freud, S. (1935). A general introduction to psycho-

analysis. New York: Clarion Books.

Gulya, M., Rovee-Collier, C., Galluccio, L., & Wilk,

A. (1998). Memory processing of a serial list by

very young infants. Psychological Science, 9,

303–307.

Hartshorn, K. (1998). The effect of reinstatement on

infant long-term retention. Unpublished doc-

toral dissertation, Rutgers University, New

Brunswick, NJ.

Hayne, H., MacDonald, S., & Barr, R. (1997).

Developmental changes in the specificity of

memory over the second year of life. Infant

Behavior and Development, 20, 233–245.

Fig. 6. Maximum duration of retention of individual 2-month-olds who were Hildreth, K., & Rovee-Collier, C. (1999). Decreases

reminded every 3 weeks through 26 weeks of age (open squares) relative to the max- in the latency of priming over the first year of life.

imum duration of retention of unreminded infants (solid line, from Fig. 4). The Manuscript submitted for publication.

Mandler, J.M. (1998). Representation. In W. Damon

dashed line, fitted by eye, extrapolates the original retention function through 30 (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 2.

months of age. By following each arrow to a point on the function and reading down Cognition, perception, and language (pp.

to the x-axis, one can determine the age equivalent for the duration of retention of 255–308). New York: Wiley.

each reminded 2-month-old. McKee, R.D., & Squire, L.R. (1993). On the devel-

opment of declarative memory. Journal of

Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and

nonverbal to verbal retrieval cues Cognition, 19, 397–404.

Recommended Reading Nelson, K. (1990). Remembering, forgetting, and

or any other contextual change— childhood amnesia. In R. Fivush & J.A.

Hudson (Eds.), Knowing and remembering in

either natural or perceived—would Campbell, B.A., & Jaynes, J. (1966). young children (pp. 301–316). Cambridge,

lessen the probability that a memo- Reinstatement. Psychological Re- England: Cambridge University Press.

ry encoded in infancy would be re- view, 73, 478–480. Piaget, J. (1952). Origins of intelligence in children

Gulya, M., Rovee-Collier, C., Gal- (M. Cook, Trans.). New York: International

trieved later in life. In addition, be- luccio, L., & Wilk, A. (1998). (See

Universities Press.

Pillemer, D.B., & White, S.H. (1989). Childhood

cause contextual information References) events recalled by children and adults. In H.W.

disappears from memories that Hartshorn, K., Rovee-Collier, C., Reese (Ed.), Advances in child development and

Gerhardstein, P., Bhatt, R.S., behavior (Vol. 21, pp. 297–340). New York:

have been reactivated once or Academic Press.

Wondoloski, T.L., Klein, P., Gilch, Rovee-Collier, C. (1997). Dissociations in infant

twice, older children and adults J., Wurtzel, N., & Campos-de- memory: Rethinking the development of

may actually remember a number Carvalho, M. (1998). The onto- implicit and explicit memory. Psychological

geny of long-term memory over Review, 104, 467–498.

of early-life events but not know Rovee-Collier, C., Hartshorn, K., & DiRubbo, M.

where or when they occurred. In the first year-and-a-half of life. (in press). Long-term maintenance of infant

Developmental Psychobiology, 32, memory. Developmental Psychobiology.

short, even if an appropriate re- 1–31. Tulving, E., Schacter, D.L., & Stark, H.A. (1982).

trieval cue were to recover an early Hayne, H., MacDonald, S., & Barr, R. Priming effects in word-fragment completion

are independent of recognition memory.

memory later in life, a person (1997). (See References) Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning,

would probably be unable to iden- Rovee-Collier, C. (1997). (See Refer- Memory, and Cognition, 8, 336–342.

ences) Watson, J.B. (1930). Behaviorism. Chicago:

tify it as such. University of Chicago Press.

Copyright © 1999 American Psychological Society

You might also like

- Infantile Amnesia: A Neurogenic HypothesisDocument12 pagesInfantile Amnesia: A Neurogenic HypothesisrocioNo ratings yet

- Behne 2005Document10 pagesBehne 2005franciscoNo ratings yet

- Vsms ManualDocument8 pagesVsms ManualAkanksha MehtaNo ratings yet

- Estrategias de MemoriaDocument10 pagesEstrategias de MemoriaKari GrechiNo ratings yet

- Rovee-Collier, C. (2011) Preserving Infant Memories - en Psychology and The Real WorldDocument4 pagesRovee-Collier, C. (2011) Preserving Infant Memories - en Psychology and The Real WorldJuan MezaNo ratings yet

- Exam 3 CoverageDocument11 pagesExam 3 CoverageSOFHIA CLAIRE SUMBAQUILNo ratings yet

- Infant Wake After Sleep Onset Serves As A Marker For Different Trajectories in Cognitive DevelopmentDocument10 pagesInfant Wake After Sleep Onset Serves As A Marker For Different Trajectories in Cognitive DevelopmentSrii AgustiniNo ratings yet

- NeuroscientistDocument5 pagesNeuroscientistMouhamadou Moukhtar SarrNo ratings yet

- Child and Adolescent ReviewerDocument8 pagesChild and Adolescent ReviewerMarjorie RagilesNo ratings yet

- Developmental DelayDocument2 pagesDevelopmental DelayTonny MachariaNo ratings yet

- 1995 Akshamoff Stiles Development ROCFT 2Document12 pages1995 Akshamoff Stiles Development ROCFT 2Liad BelaNo ratings yet

- Developmental Dissociation Between TheDocument9 pagesDevelopmental Dissociation Between ThemeiselinaNo ratings yet

- Communicating With Children and Adolescents-3Document8 pagesCommunicating With Children and Adolescents-3AANo ratings yet

- (1994) DROR - Mental Imagery and AgingDocument13 pages(1994) DROR - Mental Imagery and AgingNathália QueirózNo ratings yet

- U6 Wa Educ 5410Document5 pagesU6 Wa Educ 5410TomNo ratings yet

- 20 Brain TrustDocument6 pages20 Brain TrusttomcorreaNo ratings yet

- Emotional Expressions of Young Infants and ChildrenDocument23 pagesEmotional Expressions of Young Infants and ChildrenwavennNo ratings yet

- AnnNYAcadSci85 444 78Document19 pagesAnnNYAcadSci85 444 78Dana MunteanNo ratings yet

- Memory and Early Brain DevelopmentDocument6 pagesMemory and Early Brain Developmentwidya dwi agustinNo ratings yet

- Measuring Children's Attention Span A Microcomputer Assessment TechniqueDocument7 pagesMeasuring Children's Attention Span A Microcomputer Assessment TechniqueSara H.No ratings yet

- Melt Zoff 1990Document37 pagesMelt Zoff 1990David SilRzNo ratings yet

- Insel 2001Document8 pagesInsel 2001AugustinNo ratings yet

- Untitled DocumentDocument4 pagesUntitled DocumentsustiguerchristianpaulNo ratings yet

- RSTB 2002 1202Document16 pagesRSTB 2002 1202J M Cruz Ortiz YukeNo ratings yet

- Society For Research in Child Development, Wiley Child DevelopmentDocument25 pagesSociety For Research in Child Development, Wiley Child Developmentcecilia martinezNo ratings yet

- Go To Page Word 2022 2 1Document17 pagesGo To Page Word 2022 2 1api-621033980No ratings yet

- Flavell 1999Document17 pagesFlavell 1999OscarNo ratings yet

- Teaching With The Teen Brain in Mind: 10 Top TipsDocument2 pagesTeaching With The Teen Brain in Mind: 10 Top TipschrisNo ratings yet

- Adolescent BRain by John SantrockDocument2 pagesAdolescent BRain by John SantrockTharshanraaj RaajNo ratings yet

- Early ChildhoodDocument5 pagesEarly ChildhoodRaven SandaganNo ratings yet

- Dunn, The Impact of Sensory Processing Abilities On The Daily Lives of Young Children and Their Families - A Conceptual Model, 1997 PDFDocument14 pagesDunn, The Impact of Sensory Processing Abilities On The Daily Lives of Young Children and Their Families - A Conceptual Model, 1997 PDFmacarenavNo ratings yet

- Imitation in Infancy. MimicryDocument8 pagesImitation in Infancy. MimicryJuan Victor SeminarioNo ratings yet

- Wellman, H. M., Cross, D. y Watson, J. 2001. Meta-Analysis of TheoryDocument30 pagesWellman, H. M., Cross, D. y Watson, J. 2001. Meta-Analysis of TheoryKrratozNo ratings yet

- Tarullo, Obradovic, Gunnar (2009, 0-3) Self-Control and The Developing BrainDocument7 pagesTarullo, Obradovic, Gunnar (2009, 0-3) Self-Control and The Developing BrainCerasela Daniela BNo ratings yet

- Article With Peer Commentaries and Response Neural Plasticity and Human Development: The Role of Early Experience in Sculpting Memory SystemsDocument16 pagesArticle With Peer Commentaries and Response Neural Plasticity and Human Development: The Role of Early Experience in Sculpting Memory SystemsEnus SchlickerNo ratings yet

- 2005 16183 003 PDFDocument19 pages2005 16183 003 PDFFernandaGuimaraesNo ratings yet

- Making Space For LearningDocument76 pagesMaking Space For LearningLeah DowdellNo ratings yet

- Shum 1999Document11 pagesShum 1999Andrea Gallo de la PazNo ratings yet

- Didactics ExamDocument11 pagesDidactics Exammaria fernanada GiraldoNo ratings yet

- Children's Haptic and Cross-Modal Recognition With Familiar and Unfamiliar ObjectsDocument15 pagesChildren's Haptic and Cross-Modal Recognition With Familiar and Unfamiliar ObjectsKentNo ratings yet

- Componentes 2Document24 pagesComponentes 2sofNo ratings yet

- Piaget - Resources PDFDocument4 pagesPiaget - Resources PDFapi-533984280No ratings yet

- Child Dev WorkbookDocument29 pagesChild Dev WorkbookDominic Bonkers StandingNo ratings yet

- Imitation and Other Minds MeltzoffDocument29 pagesImitation and Other Minds MeltzoffDiego Abraham Morales TapiaNo ratings yet

- Math and Science Skills in Stages of Development eDocument1 pageMath and Science Skills in Stages of Development eapi-338452431100% (1)

- Chap Ter 21Document21 pagesChap Ter 21Rubén Páez DíazNo ratings yet

- 2007 - Verbal Working Memory in Children With Mild Intellectual DisabilitiesDocument8 pages2007 - Verbal Working Memory in Children With Mild Intellectual DisabilitiesEl Tal RuleiroNo ratings yet

- Kognitivni Razvoj U Odojastvu PERCEPCIJADocument36 pagesKognitivni Razvoj U Odojastvu PERCEPCIJAIvan DjukicNo ratings yet

- Detayson - SPED 540 Week 5 FLADocument19 pagesDetayson - SPED 540 Week 5 FLAMary Rosedy DetaysonNo ratings yet

- Cognitive DevelopmentDocument15 pagesCognitive DevelopmentAryan TomarNo ratings yet

- Perceived Effects of Lack of Sleep To The Class Performance of Grade 11 Humanities and Social Science 2Document7 pagesPerceived Effects of Lack of Sleep To The Class Performance of Grade 11 Humanities and Social Science 2Dimape Chavez AlisonNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 2018Document12 pagesChapter 3 2018UshaNo ratings yet

- Handouts (Jean Piaget) (Personal Development)Document1 pageHandouts (Jean Piaget) (Personal Development)CyberR.DomingoNo ratings yet

- Gesell, A. Monthly Increments of Development in InfancyDocument6 pagesGesell, A. Monthly Increments of Development in InfancyRodolfo van GoodmanNo ratings yet

- Adolescents' Performance On The Iowa Gambling Task: Implications For The Development of Decision Making and Ventromedial Prefrontal CortexDocument11 pagesAdolescents' Performance On The Iowa Gambling Task: Implications For The Development of Decision Making and Ventromedial Prefrontal CortexVuk KolarevicNo ratings yet

- The Emergence and Early Development of Autobiographical MemoryDocument25 pagesThe Emergence and Early Development of Autobiographical MemoryJuan Manuel RozaNo ratings yet

- Ordinary Magic: Resilience Processes in DevelopmentDocument12 pagesOrdinary Magic: Resilience Processes in DevelopmentCristina EneNo ratings yet

- Changes in The Brain of A TeenagerDocument1 pageChanges in The Brain of A TeenagerSupremacus ExcelsusNo ratings yet

- Theory ToolkitDocument20 pagesTheory ToolkitAngel TNo ratings yet

- Animal Psychology - Discover Which Role it Plays in Our LifeFrom EverandAnimal Psychology - Discover Which Role it Plays in Our LifeNo ratings yet

- Microdyn Bio Cel L 2Document2 pagesMicrodyn Bio Cel L 2antegeia2222No ratings yet

- Europe Environment ConcersDocument25 pagesEurope Environment Concersantegeia2222No ratings yet

- 1101 Mast LowDocument8 pages1101 Mast Lowantegeia2222100% (1)

- Safety Catalog SOFAMEL 2011Document80 pagesSafety Catalog SOFAMEL 2011antegeia2222100% (3)

- GE Multilin Relay Selection GuideDocument40 pagesGE Multilin Relay Selection GuideSaravanan Natarajan100% (1)

- History of Organizational DevelopmentDocument4 pagesHistory of Organizational DevelopmentAntony OmbogoNo ratings yet

- Paper 3Document14 pagesPaper 3Yousef ShahwanNo ratings yet

- Multiple Response Optimization of Heat Shock Process For Separation of Bovine Serum Albumin From PlasmaDocument11 pagesMultiple Response Optimization of Heat Shock Process For Separation of Bovine Serum Albumin From PlasmaJavier RigauNo ratings yet

- Finding The Answers To The Research Questions (Qualitative) : Quarter 4 - Module 5Document39 pagesFinding The Answers To The Research Questions (Qualitative) : Quarter 4 - Module 5Jernel Raymundo80% (5)

- Open Book ExamsDocument4 pagesOpen Book ExamsBhavnaNo ratings yet

- Research ProposalDocument7 pagesResearch Proposal111adi100% (1)

- Psychological Contract Inventory-RousseauDocument30 pagesPsychological Contract Inventory-RousseauMariéli CandidoNo ratings yet

- Business Report Writing: Information Systems in ContextDocument17 pagesBusiness Report Writing: Information Systems in Contextjoeynguyen1302No ratings yet

- Shared Value Literature Review Implications For FuDocument14 pagesShared Value Literature Review Implications For Fumonu100% (1)

- Comparison of HUMS Benefits-A Readiness ApproachDocument9 pagesComparison of HUMS Benefits-A Readiness ApproachHamid AliNo ratings yet

- HJRS DataDocument58 pagesHJRS DataGoldenNo ratings yet

- Appendix g.3 Qra Modelling r2Document10 pagesAppendix g.3 Qra Modelling r2ext.diego.paulinoNo ratings yet

- Obstacles To Teaching Gifted Students From The Point of View of Female Teachers in The Middle and High School in JeddahDocument22 pagesObstacles To Teaching Gifted Students From The Point of View of Female Teachers in The Middle and High School in JeddahBASMA GHNo ratings yet

- Comparing and Contrasting Quantitative and Qualitative ResearchDocument4 pagesComparing and Contrasting Quantitative and Qualitative ResearchJose Angelo Soler NateNo ratings yet

- Vercel 1Document28 pagesVercel 1Cristy Mae Almendras SyNo ratings yet

- Sports Information Systems-A Systematic ReviewDocument23 pagesSports Information Systems-A Systematic ReviewRajesh Mandal100% (1)

- UPB HES SO at PlantCLEF 2017 Automatic Plant Image Identification Using Transfer Learning Via Convolutional Neural NetworksDocument9 pagesUPB HES SO at PlantCLEF 2017 Automatic Plant Image Identification Using Transfer Learning Via Convolutional Neural NetworksAnonymous ntIcRwM55RNo ratings yet

- FTC 1 Unit 1Document9 pagesFTC 1 Unit 1Lady lin BandalNo ratings yet

- Worksheet in GE Math: Wk-12 Statistics Measures of DispersionDocument4 pagesWorksheet in GE Math: Wk-12 Statistics Measures of DispersionAngel OreiroNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Motivasi Dan PromkesDocument6 pagesJurnal Motivasi Dan PromkesRizki DianraNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument4 pagesCase StudyZack MarksNo ratings yet

- COMBRI Design Manual Part I EnglishDocument296 pagesCOMBRI Design Manual Part I EnglishJames EllisNo ratings yet

- Lecture 10 Risk 2122BBDocument43 pagesLecture 10 Risk 2122BBCloseup ModelsNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Topics For Physical ScienceDocument5 pagesResearch Paper Topics For Physical Sciencegooietrif100% (1)

- Chem3pracmanual 16-02-17Document346 pagesChem3pracmanual 16-02-17Naufal ShukriNo ratings yet

- Syllabus - BKAA2013 - 1 - (1) A142Document7 pagesSyllabus - BKAA2013 - 1 - (1) A142AwnieAzizanNo ratings yet

- ATS1261 Major Assessment 1 - Tho Tony Nguyen ID 24212792Document13 pagesATS1261 Major Assessment 1 - Tho Tony Nguyen ID 24212792Aaron CraneNo ratings yet

- Ranit - Michael Book1 5 (Eco Lodge Tourism Facility) 1Document61 pagesRanit - Michael Book1 5 (Eco Lodge Tourism Facility) 1MICHAEL RANIT0% (1)

- PWP (WithOUT Bulk Sampling) - Mashau Capital (Pty) LTD FreeStateDocument53 pagesPWP (WithOUT Bulk Sampling) - Mashau Capital (Pty) LTD FreeStateNkhophele GeoEnvironmentalNo ratings yet