Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Eurozone Crisis

Uploaded by

robinaryaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Eurozone Crisis

Uploaded by

robinaryaCopyright:

Available Formats

The eurozone ﴾debt﴿ crisis – causes and

crisis response

Economic Report

Maartje Wijffelaars and Herwin Loman

To the Eurzone (debt) crisis overview page

The eurozone crisis could develop due to lack of mechanisms to prevent the build‐up of macro‐

economic imbalances.

Given limited access to other sources of finance and limited fiscal transfers, the ECB played a

crucial role in the crisis response.

External assistance only came after extreme market stress. The implicit promise of the ECB to act

as a lender of last resort countries and government was necessary to re‐establish market access.

Program countries in particular had to push through reforms and severe austerity measures.

By definition, crisis countries were not able to use monetary and exchange rate policy, but, given

the chaos that it would likely have resulted in, euro‐exit remained an unappealing alternative.

Introduction

In this report, we outline how the eurozone crisis has evolved, with a special focus on peripheral member

states, i.e. Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Italy, Spain and Cyprus. We discuss how European Monetary Union ﴾EMU﴿

membership shaped both the economic crisis itself and the crisis response. As this study does not provide a

counterfactual, the conclusions do not necessarily imply that crisis hit countries would have been better off

outside the euro area ﴾for information on the benefits and costs of membership see for example Baldwin et al.,

2008; Mongelli, 2010; Rabobank, 2013﴿﴿. For more detailed information about the specific causes and

resolution of the crisis for each crisis country please see Eurozone ﴾debt﴿ crisis: Country profiles Cyprus, Greece,

Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Spain.

The Causes

The eurozone ﴾debt﴿ crisis was caused by ﴾i﴿ the lack of a﴾n﴿ ﴾effective﴿ mechanisms / institutions to prevent the

build‐up of macro‐economic and, in some countries, fiscal imbalances and ﴾ii﴿ the lack of common eurozone

institutions to effectively absorb shocks ﴾also see Rabobank, 2012; Rabobank, 2013﴿.

Lower borrowing costs following the entry into the euro area led to large intra‐eurozone capital flows,

primarily in the form of banks loans, resulting in significant increases of primarily private, and in some cases

Rabo Research | Economic Research December 18, 2015 | 1/5

https://economics.rabobank.com/publications/2015/december/the%2Deurozone%2Ddebt%2Dcrisis%2D%2Dcauses%2Dand%2Dcrisis%2Dresponse/

also public sector indebtedness in peripheral member states. Cheap ﴾foreign﴿ credit was often not used for

productive investment. Instead it was to a large extent used to finance consumption, an oversupply of housing

and, in some countries, irresponsible fiscal policies ﴾figure 1﴿. Meanwhile, partially as a result, the

competitiveness of most Southern eurozone member states deteriorated substantially in the years after euro

entry vis‐à‐vis their Northern counter parts, especially relative to Germany, which undertook wage moderation

in this period ﴾figure 2﴿. Accordingly, most peripheral countries ran large current account deficits ﴾figure 3﴿ and

experienced a ﴾further﴿ deterioration in their external investment positions.

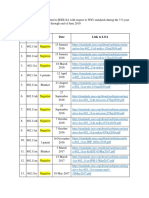

Figure 1:Fiscal stance prior to the crisis varies Figure 2: Loss of competitiveness in most

strongly between countries peripheral member states

Source: Macrobond, Eurostat Source: Macrobond, European Commission

Figure 3: Peripheral countries ran large current While especially the ﴾peripheral﴿ countries with large

account deficits housing market booms ﴾i.e. Ireland and Spain﴿ were

already seriously affected by the Great Recession, a

severe sovereign debt crisis started when the Greek

government was no longer able to finance its debt

on the markets in 2010. Rising concerns about

Greece’s fiscal problems spread rapidly to the other

peripheral member states due to the lack of

common eurozone wide institutions to absorb

shocks and growing uncertainty about the

interpretation of the EU’s ‘non‐bailout’ clause and

the willingness of eurozone member states to

support weaker member states and the currency

Source: Macrobond, IMF

union itself. Strong reliance in peripheral countries

on external capital and interlinkages between

governments and banks worsened these problems. As intra‐eurozone capital flows fell sharply, the peripheral

countries were confronted with a sudden stop of capital inflows and a strong tightening of financial conditions

for sovereigns, banks, companies and households. Below we discuss how euro membership has had an impact

on the crisis response.

The Crisis response

External assistance provided as part of eurozone membership…

The ECB played a crucial role in the crisis response. From the start of the crisis, particularly through its longer‐

term refinancing operations ﴾LTRO﴿ programs, the ECB mitigated the negative effects of rapidly reversing

cross‐border private capital flows. Growing divergence in Target II balances within the Eurosystem substituting

for private intra‐eurozone loans reflected this assistance. By providing cheap credit the ECB has thus saved the

Rabo Research | Economic Research December 18, 2015 | 2/5

https://economics.rabobank.com/publications/2015/december/the%2Deurozone%2Ddebt%2Dcrisis%2D%2Dcauses%2Dand%2Dcrisis%2Dresponse/

banking sectors in, and thereby the economies of, the crisis‐hit countries from a collapse. Other eurozone

member states also benefitted, as a collapse would have had a severe, and possibly fatal, impact on the

monetary union as a whole ﴾Rabobank, 2013﴿.

Access to other sources of finance was more constrained. Financial support packages in the form of official

intra‐eurozone and IMF‐loans[1] also helped accommodate the balance of payments, banking and sovereign

debt crises that the peripheral countries fell prey to. However, sovereign bond yields, which had risen to

elevated levels in all countries, only fell to more sustainable levels after Mario Draghi’s promise in July 2012 to

do “whatever it takes” to preserve the euro and the subsequent announcement of Outright Monetary

Transactions[2] ﴾figure 4﴿. As a result, most crisis countries and governments gradually regained market access.

In contrast to more regular, politically integrated currency areas, due to the limited size of the budget of the

European Commission and the fact that support was given in the form of loans and not grants, the size of fiscal

transfers within the euro area was and is very small. This made the adjustment process for peripheral eurozone

members more difficult. External support in the form of loans together with a strong reluctance among

eurozone member states to allow sovereign defaults to take place, resulted in a further build‐up of ﴾external﴿

public debt, particularly in Greece ﴾figure 5﴿.

Figure 4: Government bond yields have fallen to Figure 5: Large external public debt increases

below pre‐crisis rates

Source: Macrobond, World Bank

Source: Macrobond

…but only after heightened market stress…

External assistance only came after extreme market stress. The eurozone wide crisis response was severely

handicapped by the lack of supranational economic institutions. For a long time, it was not clear to what

extent other eurozone members and the ECB and other European institutions were willing to support the crisis

countries. Within the eurozone, there was initially no central bank that could act as a lender of last resort for

sovereigns ﴾De Grauwe, 2011﴿[3]. As a result, investors got concerned about the ability of peripheral member

states to service their public debt as well as the possibility of a euro area break up. This severely constrained

liquidity, especially in Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Italy, Spain and Cyprus. Ultimately, it was the intense market

pressure that moved fellow Eurozone members and institutions like the IMF and the ECB to extend financial

assistance..

…accompanied by austerity and reforms…

In return for financial support from other eurozone members, programme countries ﴾Greece, Ireland, Portugal,

Spain and Cyprus﴿ had to push through reforms and severe austerity measures. Italy never requested a support

programme, but implemented austerity measures to comfort financial markets and to live up to Europe’s

Rabo Research | Economic Research December 18, 2015 | 3/5

https://economics.rabobank.com/publications/2015/december/the%2Deurozone%2Ddebt%2Dcrisis%2D%2Dcauses%2Dand%2Dcrisis%2Dresponse/

budget rules. In all the crisis countries, austerity strongly contributed to high unemployment ﴾figure 6﴿ and a

sharp and protracted contraction of GDP ﴾figure 7﴿.

Figure 6: Unemployment rates have increased Figure 7: GDP volume still below pre‐crisis peak

significantly in most crisis countries

Source: Macrobond, Eurostat Source: Macrobond, Eurostat

On top of the conditions tied to financial support programmes, EU budget rules also constrained non‐crisis

eurozone countries from supporting domestic demand through fiscal policy. The fact that core member states

also tightened their budgets during the crisis years, made the adjustment process for peripheral eurozone

members even more difficult.

While fiscal profligacy was one of the main causes of the crisis in some countries, particularly Greece, a slower

pace of fiscal adjustment could have reduced the negative impact of the adjustment process. Moreover,

eurozone wide contractionary fiscal policy limited the effectiveness of expansionary monetary policy.

… and EMU membership did not allow countries to employ

monetary and exchange rate policy

As members of a currency union, individual eurozone countries were by definition unable to individually

employ exchange rate or monetary policy to address competitiveness problems and stimulate growth. As a

result, countries had to resort to internal devaluation, i.e. reducing labour costs, at the cost of a further

contraction of the economy and higher unemployment. However, currency devaluation via euro‐exit would

only have increased the peripheral countries’ external debt challenges. Furthermore, euro exit would have

created chaos, both for exiting countries themselves and for the other member states, as an exit would have

increased uncertainty about the future of the ﴾remainder of the﴿ eurozone.

Footnotes

[1] Union wide financial support funds ﴾first EFSF and later ESM﴿ were set up to prevent sovereign defaults and

related contagion risk. Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain and Cyprus received financial support via these funds.

[2] Afterwards, the launch of quantitative easing by the ECB in March 2015 has resulted in further downwards

pressure on yields.

[3] Since the introduction of the Outright Monetary Transactions ﴾OMT, 2012﴿, and especially since the formal

approval of its existence by the European Constitutional Court ﴾2015﴿, the ECB can also buy government

bonds in unlimited quantities. The main difference between monetary financing of government debt within

and outside the EMU is that support via the OMT is conditional on an austerity and reform programme. This is

Rabo Research | Economic Research December 18, 2015 | 4/5

https://economics.rabobank.com/publications/2015/december/the%2Deurozone%2Ddebt%2Dcrisis%2D%2Dcauses%2Dand%2Dcrisis%2Dresponse/

important as structural reforms tend to increase the sustainability of government debt in the long term and

this could help to reduce moral hazard risks. Outside the EMU, a Central Bank is unlikely to be able to request

the government to push through reforms in exchange for government bond purchases. That said, the

conditionality makes the emergency backstop subject to political risk.

Author﴾s﴿

Maartje Wijffelaars Herwin Loman

RaboResearch Global Economics +31 30 21 62666

+31 30 21 68740 economics@rn.rabobank.nl

Maartje.Wijffelaars@rabobank.nl

Rabo Research | Economic Research December 18, 2015 | 5/5

https://economics.rabobank.com/publications/2015/december/the%2Deurozone%2Ddebt%2Dcrisis%2D%2Dcauses%2Dand%2Dcrisis%2Dresponse/

You might also like

- Combinepdf PDFDocument487 pagesCombinepdf PDFpiyushNo ratings yet

- Cameron, Et Al v. Apple - Proposed SettlementDocument37 pagesCameron, Et Al v. Apple - Proposed SettlementMikey CampbellNo ratings yet

- Maint BriefingDocument4 pagesMaint BriefingWellington RamosNo ratings yet

- Exception Report Document CodesDocument33 pagesException Report Document CodesForeclosure Fraud100% (1)

- En Banc G.R. No. L-16439 July 20, 1961 ANTONIO GELUZ, Petitioner, vs. The Hon. Court of Appeals and Oscar Lazo, RespondentsDocument6 pagesEn Banc G.R. No. L-16439 July 20, 1961 ANTONIO GELUZ, Petitioner, vs. The Hon. Court of Appeals and Oscar Lazo, Respondentsdoc dacuscosNo ratings yet

- Professional Practice of Accounting With AnswerDocument12 pagesProfessional Practice of Accounting With AnswerRNo ratings yet

- Miaa Vs CA Gr155650 20jul2006 DIGESTDocument2 pagesMiaa Vs CA Gr155650 20jul2006 DIGESTRyla Pasiola100% (1)

- Allied Banking Corporation V BPIDocument2 pagesAllied Banking Corporation V BPImenforever100% (3)

- European-Debt Crisis - WikipediaDocument53 pagesEuropean-Debt Crisis - WikipediaShashank Salil ShrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Global Network: Brazil The PhilippinesDocument1 pageGlobal Network: Brazil The Philippinesmayuresh1101No ratings yet

- Application Form For For Testing Labs ISO17025Document14 pagesApplication Form For For Testing Labs ISO17025PK Jha100% (2)

- Greece's Debt Crisis ExplainedDocument6 pagesGreece's Debt Crisis ExplainedNgurah MahendraNo ratings yet

- The Eurozone (Debt) Crisis - Causes and Crisis ResponseDocument5 pagesThe Eurozone (Debt) Crisis - Causes and Crisis Response7 UpNo ratings yet

- Fixed Income Securities: Essay AssignmentDocument3 pagesFixed Income Securities: Essay AssignmentSheeraz AhmedNo ratings yet

- 1 DissertationsDocument11 pages1 DissertationsKumar DeepanshuNo ratings yet

- Euro Debt Crises: Written by Shoaib YaqoobDocument4 pagesEuro Debt Crises: Written by Shoaib Yaqoobhamid2k30No ratings yet

- European Sovereign Debt Crisis - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument38 pagesEuropean Sovereign Debt Crisis - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediatsnikhilNo ratings yet

- The Eurozone in Crisis:: Professor Assaf RazinDocument59 pagesThe Eurozone in Crisis:: Professor Assaf RazinUmesh YadavNo ratings yet

- Contagious Effects of Greece Crisis On Euro-Zone StatesDocument10 pagesContagious Effects of Greece Crisis On Euro-Zone StatesSidra MukhtarNo ratings yet

- National Law Institute University: Greek Sovereign Debt CrisisDocument15 pagesNational Law Institute University: Greek Sovereign Debt Crisisalok mishraNo ratings yet

- Eurozone CrisisDocument14 pagesEurozone CrisisMaria MeșinăNo ratings yet

- Study Guide Topic A: European CouncilDocument9 pagesStudy Guide Topic A: European CouncilAaqib ChaturbhaiNo ratings yet

- Financial Crisis: Bank Run. Since Banks Lend Out Most of The Cash They Receive in Deposits (See FractionalDocument8 pagesFinancial Crisis: Bank Run. Since Banks Lend Out Most of The Cash They Receive in Deposits (See FractionalRabia MalikNo ratings yet

- Behind The Euro CrisisDocument4 pagesBehind The Euro CrisisKostas GeorgioyNo ratings yet

- What Is The European DebtDocument32 pagesWhat Is The European DebtVaibhav JainNo ratings yet

- La Crisis de Deuda en Zona Euro 2011Document10 pagesLa Crisis de Deuda en Zona Euro 2011InformaNo ratings yet

- Greece Economic CrisisDocument32 pagesGreece Economic CrisisJOANNA ANGELA INGCONo ratings yet

- European Sovereign-Debt Crisis: o o o o o o o oDocument34 pagesEuropean Sovereign-Debt Crisis: o o o o o o o oRakesh ShettyNo ratings yet

- Greece Debt Crisis ExplainedDocument4 pagesGreece Debt Crisis ExplainedLee SharpNo ratings yet

- The European Debt Crisis: HistoryDocument7 pagesThe European Debt Crisis: Historyaquash16scribdNo ratings yet

- Huhu PDFDocument11 pagesHuhu PDFSam GitongaNo ratings yet

- Final TestDocument4 pagesFinal TestBilal SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Euro Debt CrisisDocument2 pagesEuro Debt CrisisAmrita KarNo ratings yet

- Greece Crisis 2010Document26 pagesGreece Crisis 2010Kamalpreet KaurNo ratings yet

- European Debt CrisisDocument3 pagesEuropean Debt CrisisVivek SinghNo ratings yet

- Group 5bDocument20 pagesGroup 5bAnkit SinghviNo ratings yet

- Austerity Measures & Euro Crisis: TeamDocument4 pagesAusterity Measures & Euro Crisis: Teamankushkumar2000No ratings yet

- The Europea Debt: Why We Should Care?Document4 pagesThe Europea Debt: Why We Should Care?Qraen UchenNo ratings yet

- Explained in 10 Sheets: Europe and The Global Financial CrisisDocument26 pagesExplained in 10 Sheets: Europe and The Global Financial CrisismanishkhondeNo ratings yet

- European Sovereign Debt Crisis: PiigsDocument11 pagesEuropean Sovereign Debt Crisis: PiigsBismahqNo ratings yet

- Global Ebrief Subject: What The Past Could Mean For Greece, JapanDocument5 pagesGlobal Ebrief Subject: What The Past Could Mean For Greece, Japandwrich27No ratings yet

- GRP 7Document19 pagesGRP 7Khushi ShahNo ratings yet

- A Project Report in EepDocument10 pagesA Project Report in EepRakesh ChaurasiyaNo ratings yet

- Default and Exit From The Eurozone: A Radical Left Strategy - LapavitsasDocument10 pagesDefault and Exit From The Eurozone: A Radical Left Strategy - Lapavitsasziraffa100% (1)

- Vignette #5-Affirming Conditionality: From The SMP To OMTDocument14 pagesVignette #5-Affirming Conditionality: From The SMP To OMTGandhi Jenny Rakeshkumar BD20029No ratings yet

- European Crisis US BANKDocument6 pagesEuropean Crisis US BANKEKAI CenterNo ratings yet

- Greece Crisis ExplainedDocument14 pagesGreece Crisis ExplainedAshish DuttNo ratings yet

- PB 2011-06Document8 pagesPB 2011-06BruegelNo ratings yet

- Eurozone Debt Crisis 2009 FinalDocument51 pagesEurozone Debt Crisis 2009 FinalMohit KarwalNo ratings yet

- Causes of The Eurozone Crisis: A SummaryDocument2 pagesCauses of The Eurozone Crisis: A SummaryMay Yee KonNo ratings yet

- The Greek - Sovereign Debt CrisisDocument13 pagesThe Greek - Sovereign Debt Crisischakri5555No ratings yet

- Eurozone Crisis and Its Impact On Indian Economy 4800 +Document16 pagesEurozone Crisis and Its Impact On Indian Economy 4800 +Bhavesh Rockers GargNo ratings yet

- IMF Debt Markets - December 2013Document63 pagesIMF Debt Markets - December 2013Gold Silver WorldsNo ratings yet

- Compare and Contrast The Eurozone Debt Crisis of The 2000 and The LDC Crisis of 1980s. What Lessons Can Be Learnt From Both CrisisDocument12 pagesCompare and Contrast The Eurozone Debt Crisis of The 2000 and The LDC Crisis of 1980s. What Lessons Can Be Learnt From Both CrisisphlupoNo ratings yet

- Greek Financial CrisisDocument22 pagesGreek Financial CrisisOptionTradeNo ratings yet

- Euro Zone Crisis: A Macroeconomic StudyDocument25 pagesEuro Zone Crisis: A Macroeconomic StudyAnirban ChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- European Debt CrisisDocument13 pagesEuropean Debt Crisisjaguark2210No ratings yet

- Greece's Mismanagement of Fiscal PolicyDocument5 pagesGreece's Mismanagement of Fiscal PolicyShrey ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- European Debt CrisisDocument42 pagesEuropean Debt CrisisjavictoriNo ratings yet

- Euro Debt CrisisDocument1 pageEuro Debt CrisisMonke GaemingNo ratings yet

- Canale Crisei 2013Document12 pagesCanale Crisei 2013rorita.canaleuniparthenope.itNo ratings yet

- Greece CrisisDocument6 pagesGreece CrisisShu En SeowNo ratings yet

- Subprime Mortgage Crisis and Eurozone CrisisDocument105 pagesSubprime Mortgage Crisis and Eurozone CrisisPratibha MishraNo ratings yet

- Euro Debt-1Document7 pagesEuro Debt-1DHAVAL PATELNo ratings yet

- LEVY Inst. PN 12 11Document5 pagesLEVY Inst. PN 12 11glamisNo ratings yet

- EU Crisis and Its Effect S: Presented by Leon Emre Taha LukeDocument10 pagesEU Crisis and Its Effect S: Presented by Leon Emre Taha Lukeemre tunaNo ratings yet

- The ECB During The Sovereign Debt Crisis Since 2009Document20 pagesThe ECB During The Sovereign Debt Crisis Since 2009nthNo ratings yet

- Challenges For The Euro Area and Implications For Latvia: PolicyDocument6 pagesChallenges For The Euro Area and Implications For Latvia: PolicyBruegelNo ratings yet

- The Incomplete Currency: The Future of the Euro and Solutions for the EurozoneFrom EverandThe Incomplete Currency: The Future of the Euro and Solutions for the EurozoneNo ratings yet

- R K Mohanty: Faculty Member, Sir SPBT College, Central Bank of India, MumbaiDocument39 pagesR K Mohanty: Faculty Member, Sir SPBT College, Central Bank of India, Mumbaiyashovardhan3singhNo ratings yet

- IMF Outlook AsiaDocument122 pagesIMF Outlook AsiarobinaryaNo ratings yet

- Summary Dodd Frank ActDocument28 pagesSummary Dodd Frank ActederekNo ratings yet

- World Oil Trade and The Libyan CrisisDocument8 pagesWorld Oil Trade and The Libyan CrisisrobinaryaNo ratings yet

- Sample IPCRF Summary of RatingsDocument2 pagesSample IPCRF Summary of RatingsNandy CamionNo ratings yet

- Subercaseaux, GuillermoDocument416 pagesSubercaseaux, GuillermoMarco Cabesour Hernandez RomanNo ratings yet

- SPF 5189zdsDocument10 pagesSPF 5189zdsAparna BhardwajNo ratings yet

- Adverb18 Adjective To Adverb SentencesDocument2 pagesAdverb18 Adjective To Adverb SentencesjayedosNo ratings yet

- Interconnect 2017 2110: What'S New in Ibm Integration Bus?: Ben Thompson Iib Chief ArchitectDocument30 pagesInterconnect 2017 2110: What'S New in Ibm Integration Bus?: Ben Thompson Iib Chief Architectsansajjan9604No ratings yet

- Exclusion Clause AnswerDocument4 pagesExclusion Clause AnswerGROWNo ratings yet

- Arvind Fashions Limited Annual Report For FY-2020 2021 CompressedDocument257 pagesArvind Fashions Limited Annual Report For FY-2020 2021 CompressedUDIT GUPTANo ratings yet

- Final Report On The Audit of Peace Corps Panama IG-18-01-ADocument32 pagesFinal Report On The Audit of Peace Corps Panama IG-18-01-AAccessible Journal Media: Peace Corps DocumentsNo ratings yet

- 016 - Neda SecretariatDocument4 pages016 - Neda Secretariatmale PampangaNo ratings yet

- NSF International / Nonfood Compounds Registration ProgramDocument1 pageNSF International / Nonfood Compounds Registration ProgramMichaelNo ratings yet

- WiFi LoAs Submitted 1-1-2016 To 6 - 30 - 2019Document3 pagesWiFi LoAs Submitted 1-1-2016 To 6 - 30 - 2019abdNo ratings yet

- Internal Orders / Requisitions - Oracle Order ManagementDocument14 pagesInternal Orders / Requisitions - Oracle Order ManagementtsurendarNo ratings yet

- Certificate of Compensation Payment/Tax Withheld: Commission On ElectionsDocument9 pagesCertificate of Compensation Payment/Tax Withheld: Commission On ElectionsMARLON TABACULDENo ratings yet

- Research - Procedure - Law of The Case DoctrineDocument11 pagesResearch - Procedure - Law of The Case DoctrineJunnieson BonielNo ratings yet

- Valuation of Fixed Assets in Special CasesDocument7 pagesValuation of Fixed Assets in Special CasesPinky MehtaNo ratings yet

- SAP Project System - A Ready Reference (Part 1) - SAP BlogsDocument17 pagesSAP Project System - A Ready Reference (Part 1) - SAP BlogsSUNIL palNo ratings yet

- MIH International v. Comfortland MedicalDocument7 pagesMIH International v. Comfortland MedicalPriorSmartNo ratings yet

- Heterosexism and HomophobiaDocument6 pagesHeterosexism and HomophobiaVictorNo ratings yet

- Solved Acme Realty A Real Estate Development Company Is A Limited PDFDocument1 pageSolved Acme Realty A Real Estate Development Company Is A Limited PDFAnbu jaromiaNo ratings yet

- Full Download Introduction To Brain and Behavior 5th Edition Kolb Test Bank PDF Full ChapterDocument36 pagesFull Download Introduction To Brain and Behavior 5th Edition Kolb Test Bank PDF Full Chapternaturismcarexyn5yo100% (16)