Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Risk Management

Uploaded by

ssalaria_1Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Risk Management

Uploaded by

ssalaria_1Copyright:

Available Formats

In recent years, managers have become increas- just that.

The General Accounting Office reports

ingly aware of how their organizations can be buf- that between 1989 and 1992 the use of derivatives-

feted hy risks beyond their controi. In many cases, among them forwards, futures, options, and swaps-

fluctuations in eeonomie and financial variables grew by 145%. Much of that growth came from

such as exchange rates, interest rates, and commod- corporations: one recent study shows a more than

ity prices have had destabilizing effects on corpo- fourfold increase between 1987 and 1991 in their

rate strategies and performance. Consider the fol- use of some types of derivatives.'

lowing examples: In large part, the growth of derivatives is due to

D In the first half of 1986, world oil prices plummet- innovations by financial theorists who, during the

ed by 50%; overall, energy prices fell by 24%. While 1970s, developed new methods-such as the Black-

this was a boon to the economy as a whole, it was Scholes option-pricing formula-to value these com-

disastrous for oil producers as well as for companies plex instruments. Sueh improvements in the tech-

like Dresser Industries, which supplies ma- nology of financial engineering have helped spawn

chinery and a new arsenal of risk-management weapons.

Unfortunately, the insights of the financial engi-

neers do not give managers any

guidance on how to de-

ploy the new

A Framework for

Risk Management

by Kenneth A. Froot, David S. Scharfstein, and Jeremy C. Stein

equip-

ment to ener-

gy producers. As do-

mestic oil production collapsed, so did demand for weapons most

Dresser's equipment. The company's operating effectively. Al-

profits dropped from $292 million in 1985 to $139 though many com-

million in 1986; its stock price fell from $24 to $14; panies are heavily in-

and its capital spending decreased from $122 mil- volved in risk management, it's

lion to $71 million. safe to say that there is no single, well-accepted

D During the first half of the 1980s, the U.S. dollar set of principles that underlies their hedging pro-

appreciated by 50% in real terms, only to fall back grams. Financial managers will give different an-

to its starting point by 1988. The stronger dollar swers to even the most basic questions: What is

forced many U.S. exporters to cut prices drastically the goal of risk management? Should Dresser and

to remain competitive in global markets, reducing Caterpillar have used derivatives to insulate their

short-term profits and long-term competitiveness. stock prices from shocks to energy prices and ex-

Caterpillar, the world's largest manufacturer of change rates? Or should they have focused instead

earthmoving equipment, saw its real-dollar sales on stabilizing their near-term operating income,

decline by 45% between 1981 and 1985 before in- reported earnings, and return on equity, or on re-

creasing by 35% as the dollar weakened. Mean- moving some of the volatility from their capital

while, the company's capital expenditures fell from spending?

$713 million to $229 million before jumping to Without a clear set of risk-management goals, us-

$793 million in 1988. But by that time, Caterpillar ing derivatives can be dangerous. That has been

had lost ground to foreign competitors such as

Japan's Komatsu. Kenneth A. Froot is a professor at the Harvard Business

In principle, both Dresser and Caterpillar could School in Boston. Massachusetts. David S. Scharfstein is

the Dai'lchi Kangyo Bank Professor and Jeremy C. Stein

have insulated themselves from energy-price and the J.C. Penney Professor, at the Massachusetts Institute

exchange-rate risks by using the derivatives mar- of Technology's Sloan School of Management in Cam-

kets. Today more and more companies are doing bridge, Massachusetts.

HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW November-December 1994 91

RISK MANAGEMENT

made abundantly clear by the numerous cases of and interest rates, potentially compromising a com-

derivatives trades that have backfired in the last pany's ability to invest.

couple of years. Procter & Gamble's losses in cus- A risk-management program, therefore, should

tomized interest-rate derivatives and Metallge- have a single overarching goal: to ensure that a

sellschaft's losses in oil futures are two of the most company has the cash available to make value-en-

prominent examples. The important point is not hancing investments.

that these companies lost money in derivatives, be- By recognizing and accepting this goal, manag-

cause even the best risk-management programs ers will be better equipped to address the most

will incur losses on some trades. What's important basic questions of risk management: Which risks

is that both companies lost substantial should be hedged and whieh should be

sums of money - in the case of Met- left unhedged- What kinds of instru-

allgesellschaft, more than $1 bil- ments and trading strategies are

lion - because they took posi- appropriate- How should a

tions in derivatives that did company's risk-management

not fit well with their corpo- strategy be affected by its

rate strategies. competitors' strategies?

Our goal in this article

is to present a framework From Pharaoh to

to guide top-level man- Modern Finance

agers in developing a co-

herent risk-management Risk management is

strategy-in particular, to not a modern invention.

make sensible use of the The Old Testament tells

risk-management fire- the story of the Egyptian

power available to them Pharaoh who dreamed that

through financial deriva- seven healthy cattle were

tives.' Contrary to what senior devoured by seven sickly cat-

managers may assume, a com- tle and that seven healthy ears

pany's risk-management strategy of corn were devoured by seven

cannot be delegated to the corporate sickly ears of corn. Puzzled by the

treasurer-let alone to a hotshot financial en- dream, Pharaoh called on Joseph to interpret

gineer. Ultimately, a company's risk-management it. According to Joseph, the dream foretold seven

strategy needs to be integrated with its overall eor- years of plenty followed by seven years of famine.

porate strategy. To hedge against that risk, Pharaoh bought and

Our risk-management paradigm rests on three stored large quantities of corn. Egypt prospered dur-

basic premises: ing the famine, Joseph became the second most

D The key to creating corporate value is making powerful man in Egypt, the Hebrews followed him

good investments. there, and the rest is history.

• The key to making good investments is generat- In the Middle Ages, hedging was made easier by

ing enough cash internally to fund those invest- the creation of futures markets. Rather than buying

and storing crops, consumers could

ensure the availability and price of

Without a elear set of risk- a crop by buying it for delivery at a

predetermined price and date. And

management goals, using farmers could hedge the risk that the

price of their crops would fall by sell-

derivatives can be dangerous. ing them for later delivery at a pre-

determined price.

It is easy to see why Pharaoh, the

mentS; when companies don't generate enough consumer, and the farmer would want to hedge.

cash, they tend to cut investment more drastically The farmer's income, for example, is tied closely to

than their competitors do. the price he can get for his crop. So any risk-averse

n Cash flow-so crucial to the investment process- farmer would want to insure his income against

can often be disrupted by movements in external fluctuations in crop prices just as many working

factors such as exchange rates, commodity prices. people protect their incomes with disability insur-

92 DRAWINGS BY ERIC DEVER

ance, It's not surprising, then, that the first futures area, is that value is created on the left-hand side of

markets were developed to enable farmers to insure the balance sheet when companies make good in-

themselves more easily. vestments-in, say, plant and equipment, R&D, or

More recently, large publicly held companies market share - that ultimately increase operating

have emerged as the principal users of risk-manage- cash flows. How companies finance those invest-

ment instruments. Indeed, most new financial ments on the right-hand side of the halance sheet-

products are designed to enable corporations to whether through deht, equity, or retained earnings-

hedge more effectively. But, unlike

the farmer, the consumer, and

Pharaoh, it is not so clear why a cor-

poration would want to hedge. After

The key to making good

all, corporations are generally owned

by many small investors, each of

investments is generating the

whom bears only a small part of the

risk. In fact, Adolf A. Berle, Jr., and cash to fund them internally.

Gardiner C. Means argue in their

classic book. The Modern Corporation and Private is largely irrelevant. These decisions about finan-

Property, that the modern corporate form of organi- cial policy can affeet only how the value ereated by

zation was developed precisely to enahle entrepre- a company's real investments is divided among its

neurs to disperse risk among many small Investors. investors. But in an efficient and well-functioning

If that is true, it's hard to see why corporations capital market, they cannot affect the overall value

themselves also need to reduce risk-investors can of those investments.

manage risk on their own. If one accepts the view of Modigliani and Miller,

Until the 1970s, finance specialists accepted this it follows almost as a corollary that risk-manage-

logic. The standard view was that if an investor ment strategies are also of no consequence. They

does not want to be exposed to, say, the are purely financial transactions that

oil-price risk inherent in owning don't affect the value of a company's

Dresser Industries, he can hedge operating assets. Indeed, once the

for himself. For example, he can transaction costs associated

offset any loss on his Dresser with hedging instruments

Industries stock that might are factored in, a hard-line

come from a decline in oil Modigliani-Miller disciple

priees hy also holding the would argue against do-

stocks of companies that ing any risk manage-

generally benefit from ment at all.

oil-price declines, such Over the past two

as petrochemieal firms. decades, however, a dif-

There is thus no reason ferent view of financial

for the corporation to policy has emerged that

hedge on behalf of the in- allows a more integral

vestor. Or, put somewhat role for risk management.

differently, hedging trans- This "postmodern" para-

actions at the corporate lev- digm accepts as gospel the

el sometimes lose money and key insight of Modigliani and

sometimes make money, but on av- Miller-that value is created only

erage they break even; companies can'i when companies make good invest-

systematically make money by hedging. Un- ments that ultimately increase their operat-

like individual risk management, corporate risk ing cash flows. But it goes further by treating finan-

management doesn't hurt, hut it also doesn't help. cial policy as critical in enabling companies to

Corporate finance specialists will reeognize this make valuable investments. And it recognizes that

logic as a variant of the Modigliani and Miller theo- companies face real trade-offs in how they finance

rem, which was developed in the 1950s and hecame their investments.'

the foundation of "modern finanee." The key in- For example, suppose a company wants to add a

sight of Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller, each new plant that would expand its production capaci-

of whom won a Nohel Prize for his work in this ty. If the company has enough retained earnings to

HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW November-Decemk-r i 994 93

RISK MANAGEMENT

pay for the cost of the plant, it will use those funds sioned. The costs we have outlined make external

to build it. But if the company doesn't have the financing of any form-be it debt or equity-more

cash, it will need to raise capital from one of two expensive than internally generated funds. Given

sources: the debt market (perhaps through a bank those costs, companies prefer to fund investments

loan or a bond issue) or the equity market. with retained earnings if they can. In fact, there is a

It is unlikely that the company would decide to financial pecking order in which companies rely

issue equity. Indeed, on average, less than 2% of all first on retained earnings, then on debt, and, as a

corporate financing comes from the external equity last resort, on outside equity.

market.' Why the aversion to equity? The problem What is even more striking is that companies see

is that it's difficult for stock market investors to external financing as so costly that they actually

cut investment spending when they

don't have the internally generated

The role of risk management is to ^^^^ ^^^^ to fmance an their mvest

ment projects. Indeed, one study

ensure that a company has found that companies reduced their

capital expenditures by roughly 35

the cash available to make cents for each $1 reduction in cash

flow.'' These financial frictions thus

: investments. determine not oniy how companies

finance their investments but also

whether they are able to undertake

know the real value of a company's assets. They those investments in the first place. Internally gen-

may get it right on average, but sometimes they erated cash is therefore a competitive weapon that

price the stock too high and sometimes they price it effectively reduces a company's cost of capital and

too low. Naturally, companies will be reluctant to facilitates investment.

raise funds by selling stock when they think their This is the most critical implication of the post-

equity is undervalued. And if they do issue equity, modern paradigm, and it forms the theoretical

it will send a strong signal to the stock market that foundation of the view stated earlier-that the role

they think their shares are overvalued. In fact, of risk management is to ensure that companies

when companies issue equity, the stock price tends have the cash available to make value-enhancing

to fall by about 3%.'' The result: most companies investments. Although the practical implications

perceive equity to be a costly source of financing of this idea may seem vague, we will demonstrate

and tend to avoid it. how it can help to develop a coherent risk-manage-

The information problems that limit the appeal ment strategy.

of equity are of much less concern when it comes

to debt: most debt issues-particularly those of in-

vestment-grade companies-are easy to value even

Why Hedge?

without precise knowledge of the company's assets. Let's start with the case of a hypothetical multi-

As a result, companies are usually less worried national pharmaceutical company, Omega Drug.

about paying too high an interest rate on their bor- Omega's headquarters, production facilities, and re-

rowings than about getting too low a price for their search labs are in the United States, but roughly

equity. It's therefore not surprising that the bulk of half of its sales come from abroad, mainly Japan and

all external funding is from the debt market. Germany. Omega has several products that are still

However, debt financing is not without cost: tak- protected by patents, and it does not expeet to in-

ing on too much debt limits a company's ability to troduce any new products this year. Omega's main

raise funds later. No one wants to lend to a compa- uncertainty is the revenue it will receive from for-

ny with a large debt burden, because the company eign sales. The company can forecast its foreign

may use some of the new funds not to invest in sales volume very accurately, but the dollar value of

productive assets but to pay off the old debt. In the those sales is hard to pin down because of the un-

extreme, high debt levels can trigger distress, de- certainty inherent in exchange rates. If exchange

faults, and even bankruptcy. So while companies rates remain stable. Omega expects the dollar value

often borrow to finance their mvestnicnts, there are of its cash flow from foreign and domestic opera-

limits to how much they can or will borrow. tions to be $200 million. If, however, thc dollar ap-

The bottom line is that financial markets do not preciates substantially relative to the Japanese yen

work as smoothly as Modigliani and Miller envi- and the German mark, then Omega's cash flow will

94 HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW Ntivemiier-Dtccmber 1994

fall to $ 100 million, since the weaker yen and mark the $200 million budget was, on a relative basis,

mean that foreign cash flows are worth less in dol- roughly in line with the budgets of its principal

lars. Conversely, a significant dollar depreciation competitors.

would increase Omega's cash flow to $300 million. Given its comparatively high leverage and limit-

Each of these scenarios is equally likely. ed collateral, Omega is not in a position to borrow

Like most multinational corporations. Omega any funds to finance its R&D program. It is also re-

frequently receives calls from investment bankers luctant to issue equity. That leaves internally gen-

trying to persuade the company to hedge its foreign- erated cash as the only funding source that Omega's

exchange risk. The bankers typically present an im- managers are prepared to tap for the R&D program.

pressive set of calculations showing how Omega Therefore, fluctuations in the dollar's exchange

can reduce the risk in its earnings, cash flow, stock rate can be critical. If the dollar appreciates. Omega

price, and return on equity simply by trading on for- will have a cash flow of only $100 million to allo-

eign-exchange markets. So far. Omega has resisted cate to its RikD program - well below the desired

those overtures and has chosen not to engage in any $200 million budget. A stable dollar will generate

substantial foreign-exchange hedging. "After all," enough cash flow for the program, while a depreci-

Omega's top-level officers have

argued, "we're a pharmaceutical

company, not a bank."

Omega has one thing going for

it: a healthy skepticism of bank-

ers trying to sell their financial

services. But the bankers also

have something going for them:

the skills to insulate companies

from financial risk. What neither

the company nor the bankers

have is a well-articulated view of

the role of risk management.

The starting point for our anal-

ysis is understanding the link be-

tween Omega's cash flows and

its strategic investments, prinei-

pally its R&D program. R&D is the key to suc- ating dollar will generate an excess of $100 million.

cess in the pharmaceutical business, and its impor- (See the table "The Effect of Hedging on Omega

tance has grown dramatically during the last two Drug's R&D Investment and Value.")

decades. Twenty years ago. Omega was spending Will Omega be better off if it hedges? Suppose

8% of sales on R&D; now it is spending 12% of Omega tells its bankers to trade on its behalf so that

sales on R&D. the company's cash flows are completely insulated

Last year. Omega's R&D budget was $180 mil- from foreign-exchange risk. If the dollar appreci-

lion. In the coming year, the company would like to ates, the trades will generate a $ 100 million gain; if

spend $200 million. Omega arrived at this figure by the dollar depreciates, they'll post a $100 million

first forecasting the increase in patentable products loss. The trades will generate no gain or loss if the

that would result from a particular level of R&D. dollar remains at its current level. Effectively, the

As a second step, managers valued the increased hedging program locks in net cash flows of $200

cash flows through a diseountcd-cash-flow analy- million for Omega-the cash flows that the com-

sis. Such an approach could generate only rough es- pany would receive at prevailing exchange rates.

timates of the value of R&D because of the uncer- Whatever the exchange rate turns out to be. Omega

tainty inherent in the R&D process, but it was the will have S200 million available for RtitD-just the

best Omega could do. Specifically, the company's right amount.

calculations indicated that an R&D budget of $200 If Omega doesn't hedge, it will be able to invest

million would generate a net present value of $90 only $ 100 million in R&D if the dollar appreciates.

million, compared with $60 million for R&D bud- By hedging. Omega is able to add $100 million of

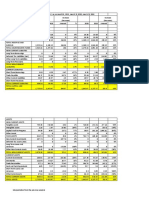

gets of $100 million and $300 million. (See the table R&D in this scenario, increasing discounted future

"Payoffs from Omega Drug's R&D Investment.") eash flows by $130 million (from $160 million to

The eompany took comfort in the knowledge that $290 million). On the other hand, if the dollar de-

HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW NovL-mbL-r-DL-ccmbcr 1994 95

RISK MANAGEMENT

'he Effect of Hedging on Omego

'rug's R&D Investment and Value

Hedge raiTuerirohi

Proceeds' Hedging*

100 100 • lCXi h 100 + 130

200 300 0

300 -100

*in miliions of dollars

predates, Omega will lose $100 million on its for- ing, the company reduces supply when there is ex-

eign-exchange transactions. However, the $130 cess supply and increases supply when there is a

million gain clearly outweighs the $100 million shortage. This aligns the internal supply of funds

loss. Overall, Omega is better off if it hedges. with the demand for funds. Of course, the average

Although this example is highly stylized, it illus- supply of funds doesn't change with hedging, be-

trates a basic principle. In general, the supply of in- cause hedging is a zero-net-present-value invest-

ternally generated funds does not equal the invest- ment: it does not create value hy itself. But it en-

ment demand for funds. Sometimes there is an sures that the company has the funds precisely

excess supply,- sometimes there is a shortage. Be- when it needs them. Because value is ultimately

cause external financing is costly, this imbalance created by making sure the company undertakes

shifts investment away from the optimal level. the right investments, risk management adds real

Risk management can reduce this imbalance and value. (See the graph "Omega Drug: Hedging with

the resulting investment distortion. It enables com- Fixed R&JD Investment.")

panies to better align their demand for funds with

their internal supply of funds. That is, risk manage-

ment lets companies transfer funds from situations When to Hedge-or Not

in which they have an excess supply to situations The basic principle outlined above is just a first

in which they have a shortage. In essence, it allows step. The real challenge of risk management is to

companies to borrow from themselves. apply it to developing strategies that deal with the

Here's another way to look at what happens. variety of risks faced by different companies.

As tbe dollar depreciates, the internal supply of What we have argued so far is that companies

funds - Omega's cash flow-increases. The demand should use risk management to align their internal

supply of funds with their demand

for funds. In the case of Omega Drug,

Risk management enables that means hedging all the exchange-

rate risk. Since we have assumed

companies to become better at that the demand for funds - the de-

sired amount of investment - isn't'

aligning the demand for funds affected by exchange rates. Omega

should stabilize its supply by in-

with the internal supply of funds. sulating its cash flows from any

changes in exchange rates. This as-

sumption may be reasonable in the

for funds - the desired level of investment - is fixed case of Omega because it is unlikely that the val-

and independent of the exchange rate. When the ue of investing in R&D in pharmaceuticals would

company doesn't hedge, demand and supply are depend very much on exchange rates. But there

equal only if the dollar remains stable. If the dollar are many instances in which exchange rates, com-

depreciates, however, supply exceeds demand; if it modity prices, or interest rates do affect the value

appreciates, supply falls short of demand. By hedg- of a company's investment opportunities. Under-

96 HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW November-Deccmbt;r 1994

standing the connection between a company's in- Omega Oil sometimes has an excess demand of $50

vestment opportunities and those key economic; million and sometimes an excess supply of $50 mil-

variables is critical to developing a coherent risk- lion; with Omega Drug, the excess demand and ex-

management strategy. cess supply were $100 million. Omega Oil, there-

Take the case of an oil company. The main risk it fore, doesn't need to hedge its oil-price risk as much

faces is changes in the price of oil. When oil prices as Omega Drug needed to hedge its foreign-ex-

fall, cash flows decline because existing oil proper- change risk. Roughly speaking, the optimal hedge

ties produce less revenue. Therefore, the company's for Omega Oil is only half that for Omega Drug.

supply of internal funds is exposed to oil-price risk Here the demand for funds increases with the

in much the same way that a multinational drug price of oil. (See the graph "Omega Oil: Hedging

company's cash flows are exposed to foreign-ex- with Oil-Price-Sensitive R&D Investment.") The

change risk. difference between supply and demand is smaller in

However, while the value of pharmaceutical the example of tbe oil company than it is wben the

R&D investment is unaffected hy exchange rates, investment level is fixed, as it was with Omega

the value of investing in the oil business falls when Drug. To align supply with demand. Omega Oil

oil prices drop. When prices are low, it's less attrac- doesn't need to hedge as much as Omega Drug did.

tive to explore for and develop new oil reserves. So Essentially, Omega Oil already has something of a

when the supply of funds is low, so is the demand huilt-in hedge.

for funds. On the flip side, when oil prices rise, cash An important point emerges from this example:

flows rise and the value of investing rises. Supply A proper risk-management strategy ensures that

and demand are both high. For an oil company, companies have the cash when they need it for in-

much more than for a pharmaceutical company, vestment, but it does not seek to insulate them

the supply of funds tends to match the demand for completely from risks of all kinds.

funds even if the company does not actively man- If Omega Oil follows our recommended strategy

age risk. As a result, there is less reason for an oil and hedges oil-price risk only partially, then its

company to hedge than there is for a multinational stock price, earnings, return on equity, and any

pharmaceutical company. number of other performance measures will fluc-

To illustrate the difference

more clearly, let's change some

of the numbers in our Omega Omega Drug: Hedging

Drug example and rename the 1th Fixed R&D Investment

company Omega Oil. Let's sup-

pose there are tbree possible oil Supply of Internal Funds

prices - low, medium, and bigb - (cash How from operations)

whicb generate cash flows of

$100 million, $200 million, and

$300 million, respectively. The

higher the oil price, tbe more

revenue Omega Oil generates on

its existing reserves.

So far, the example is exactly

the same as before. Where it dif-

fers is on the investment side.

The optimal amount of invest- Demand for Funds

ment in the low-oil-price regime (desired R&D investment)

is $130 million; in the medium-

oil-price regime, it's $200 mil-

lion; and in the high-oil-price

regime, it's $250 million. Thus,

higher oil prices make exploring

for and developing oil reserves

more attractive. In this example,

the supply of funds is not too far

off from the demand for funds Appreciating Depreciating

even if Omega Oil doesn't hedge. Dollar Dollar

HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW November-December ) 994 97

RISK MANAGEMENT

tuate with the price of oil. When oil prices are This approach helps managers address two key

low. Omega is worth less: the company's existing issues. First, it helps them identify what is worth

properties are less valuable, and it will invest less. hedging and what isn't. Worrying about stock-price

It's simply less profitable to be in the oil business, volatility in and of itself isn't worthwhile; such

and this will be reflected in Omega's performance volatility can be better managed by individual in-

measures. But there's nothing a risk-management vestors through their portfolio strategies. By con-

program can do to improve the underlying bad trast, excessive investment volatility can threaten

economics of low oil prices. The goal of risk man- a company's ability to meet its strategic objectives

agement is not to insure investors and corporate and, as a result, is worth controlling through risk

managers against oil-price risk per se. It is to en- management.

sure that companies have the cash they need to Second, this approach helps managers figure out

create value by making good investments. how much hedging is necessary. If changes in ex-

In fact, attempting to insulate investors com- change rates, commodity prices, and interest rates

pletely from oil-price risk could actually destroy lead to large imbalances in the supply and demand

value. For example, if Omega Oil were to hedge ful- for funds, then the company should hedge aggres-

ly, it would actually have an excess supply of funds sively; if not, the company has a natural hedge, and

when oil prices fall: its cash flow would be stabi- it does not need to hedge as much.

lized at $200 million, and its investment needs Managers who adopt our approach should ask

would be only $ 150 million. But when oil prices are themselves two questions: How sensitive are cash

high, just the opposite would be true: the company flows to risk variables such as exchange rates, com-

would lose so much money on its hedging position modity prices, and interest rates? and How sensi-

that it would have a shortage of funds for invest- tive are investment opportunities to those risk vari-

ment. Its net cash flows would still be only $200 ables? The answers will help managers understand

million, but its investment needs would rise to whether the supply of funds and the demand for

$250 million. In this case, hedging fully would pre- funds are naturally aligned or whether they can be

vent the company from making value-enhancing better aligned through risk management.

investments.

Guidelines for Managers

Omega Oil: Hedging ^ what follow are some guide-

Oil-Price-Sensitive R&D Investment lines for how managers can think

about risk-management issues.

Supply of Internal Funds Although these are by no means

(casn now from operations) the only issues to consider, our

suggestions should provide man-

agers with useful direction.

• Companies in the same indus-

try should not necessarily adopt

the same hedging strategy. To un-

derstand why, take the case of oil.

Even though all oil companies are

exposed to oil-price risk, some

may be exposed more than others

Demand for Funds in both their cash flows and their

(desired R&D investment) investment opportunities. Let's

compare Omega Oil with Epsilon

Oil. Omega has existing reserves

in Saudi Arabia that are a rela-

tively cheap source of oil, where-

as Epsilon gets its oil from the

North Sea, which is a relatively

expensive source. If the price of

oil falls dramatically, Epsilon

Lo^er Current Higher may be forced to shut down those

Oil Price Oil Price Oil Prke reserves altogether, wiping out an

98 HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW November-December 1994

RISK MANAGEMENT

important source of its cash flow. Omega would cy of pricing low to huild market share. Eor compa-

continue to operate its reserves because the cost of nies that make sueh investments, internally gener-

taking the oil out of the ground is still less than the ated funds are especially important. As a result,

oil price. Therefore, Epsilon's cash flows are more there may be an even greater need to align tbe sup-

sensitive to the price of oil. Hedging is more valu- ply of funds with the demand for funds through risk

able for Epsilon than it is for Omega because Ep- management.

silon's supply of funds is less in sync with its de- D Even companies with conservative capital struc-

mand for funds. tures-no debt,, lots of cash-can benefit from hedg-

Similar logic applies when the two oil companies ing. At first glance, it might appear that a company

differ in their investment opportunities. with a very conservative capital structure

Suppose instead that Omega and Ep- should be less interested in risk man-

silon both have essentially the agement. After all, such a compa-

same cash-flow streams from ny could adjust rather easily to

their existing oil properties a large drop in cash flow hy

but Epsilon is trying to de- borrowing at relatively low

velop new reserves in the cost. It wouldn't need to

North Sea, and Omega in curtail investment, and

Saudi Arabia. When the corporate value would

price of oil drops, it may not suffer much. The ba-

no longer be worthwhile sic objective of risk man-

to try to develop re- agement - aligning the

serves in the North Sea, supply of internal funds

since it is an expensive with the demand for in-

source of oil, but it may vestment f u n d i n g - h a s

be worthwhile to do so less urgency in this type of

in Saudi Arahia. Thus, the situation because managers

drop in the oil price affects can easily adjust to a supply

both companies' cash flows shortfall by borrowing. To be

equally, hut Epsilon's investment sure, hedging wouldn't hurt, hut it

opportunities fall more than Omega's migbt not help much either.

do. Because Epsilon's demand for funds is But managers in this position should ask

more in line with its supply of funds, Epsilon has themselves why they have chosen such a conserva-

less incentive to hedge than Omega does. tive capital structure. If the answer is. The world is

a risky place, and you never know what ean happen

Again, a simple message emerges: To develop a to exchange rates or interest rates, they have more

coherent risk-management strategy, companies thinking to do. What they have done is use low

must carefully articulate tbe nature of both their leverage instead of, say, the derivatives markets to

cash flows and their investment opportunities. protect against the risk in those economic vari-

Once they have done this, their efforts to align the ables. An alternative strategy would be to take on

supply of funds with the demand for funds will gen- more debt and then hedge those risks directly in the

erate the right strategies for managing risk. derivatives markets. In fact, there's something to be

D Companies may benefit from risk management said for the seeond approach: it's no more risky in

even it" they have no major investments in plant terms of the ability to make good investments than

and equipment. We define investment very hri)adly the low-deht/no-hedging strategy, but, in many

to include not just conventional investments such countries, the added debt made possible by hedging

as capital expenditures but also investments in in- allows a company to take advantage of the tax de-

tangible assets such as a well-trained workforce, duetibility of interest payments.

brand-name recognition, and market share. n Multinational companies must recognize that

In fact, companies that make these sorts of in- foreign-exchange risk affects not only cash flows

vestments may need to be even more active ahout but also investment opportunities. A number of

managing risk. After all, a capital-intensive compa- complex issues arise with multinationals, but

ny can use its newly purchased plant and equip- many of them can be illustrated with two exam-

ment as collateral to secure a loan. "Softer" invest- ples. In each example, a company is planning to

ments are harder to collateralize. It may not be so build a plant in Germany to manufacture cameras.

easy for a company to raise capital from a hank to In Example I it will sell the cameras in Germany,

fund, say, short-term losses that result from a poli-

100 HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW November-December 1994

while in Example 2 it will sell them in the United either. However, there are some situations in

States. In both cases, most of the company's cash which a company may have even greater reason to

flows come from its other businesses in the United hedge if its competitors don't. Let's continue with

States. How aggressively should it hedge the dol- the example of the camera company that is consid-

lar/mark exchange rate? ering building capacity to manufacture and sell

Example 1. If the dollar depreeiates relative to the cameras in Germany. Suppose now that its com-

mark, it will become more expensive (in dollar petitors - other camera companies with revenues

terms) to build the plant in Germany. But this does mostly in dollars - are also eonsidering building ca-

not mean that the company will want to build a pacity in Germany.

smaller plant - or scrap the plant altogether - be- If its competitors choose not to hedge, they won't

cause the marks it receives from selling cameras in be in a strong position to add capacity if the dollar

Germany will also be worth more in dollars. In oth- depreciates: they will find themselves short of

er words, because the plant's costs and revenues are marks. But that is precisely the situation in which

both mark-denominated, as long as the plant is eco- the company wants to build its plant - when its

nomically attractive today, it will still be attractive competitors' weakness reduees the likelihood of

if the dollar/mark rate changes. Therefore, just as industry overcapacity,- this makes its investment in

Omega Drug wants to maintain its R&.D despite Germany more attractive. Therefore, the company

the dollar's appreciation, this company would want should hedge to make sure it has enough cash for

to maintain its investment in Germany despite the this investment.

dollar's depreciation. This calls for fairly aggressive This is just another example of how clearly artic-

hedging against a depreciation in the dollar to en- ulating the nature of investment opportunities can

sure that the company has enough marks to build inform a company's risk-management strategy; in

the plant. this case, the investment opportunities depend on

Example 2. The answer here is a bit more com- the overall structure of the industry and on the fi-

plex. Since the company is now manufacturing nancial strength of its competitors. Thus, the same

cameras for export back to the United States, a de- elements that go into formulating a competitive

preciation in the dollar makes it less attractive to strategy should also be used to formulate a risk-

manufacture in Germany. Dollar-denominated la- management strategy.

bor costs are simply higher when the mark is more D The choice of specific derivatives cannot .simply

valuable. Thus, any depreeiation in the dollar raises be delegated to the financial specialists in the com-

the dollar cost of building the plant. But it also re- pany. It's true that many of the more technical as-

duces the dollar income the company would re- pects of derivatives trading are best left to the tech-

ceive from the plant. As a result, the company nical finance staff. But senior managers need to

might want to scale back its investment or scrap understand how the choices of financial instru-

the plant when the dollar depreci-

ates. The value of investing falls, so

there's less reason to hedge than in

Example 1. This case is analogous to The choice of specific

that of Omega Oil in that risk that

hurts cash flows - namely, a depre- derivatives should not simply

ciation of the dollar relative to the

mark-also diminishes the appeal of be delegated to the company's

investing. As a result, there is less

reason to hedge the risk. financial specialists.

Of course, this assumes that the

company hasn't yet committed to building the ments link up with the broader issues of risk-man-

plant. If it has, then it would make sense to hedge agement strategy that we have been exploring.

the short-term risk of a dollar depreciation to en- There are two key features of derivatives that a

sure that the funds are available to continue the company must keep in mind when evaluating

project. But if it hasn't committed, it is less impor- which ones to use. The first is the cash-flow impli-

tant to hedge the longer-term risks. cations of the instruments. For example, futures

D Companies should pay close attention to the contracts are traded on an exchange and require a

hedging strategies ot their competitors. It is tempt- company to mark to market on a daily basis-that

ing for managers to think that if the competition is, to put up money to compensate for any short-,

doesn't hedge, then their company doesn't need to. term losses. These expenditures can cut into the

HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW NovcmbL-r-DcLcmhcr im

RISK MANAGEMENT

cash a company needs to finance current invest- shareholders. So unless a company can explain why

ments. In contrast, over-the-counter forward con- an exotic instrument protects its investment op-

tracts-which are customized transactions arranged portunities better than a plain-vanilla one, it's bet-

with derivatives dealers-do not have this drawback ter to go witb plain vanilla.

because they do not have to be settled until the con-

tract matures. However, this advantage will proha- Wbere do managers go from here? The first step-

bly come at some cost; when a dealer writes the which may bc the hardest - is to realize that they

company a forward, he will charge a premium for cannot ignore risk management. Some managers

the risk that he hears by not extracting any pay- may be tempted to do so in order to avoid high-pro-

ments until the contract matures. file hlundcrs like those of Procter S<. Gamble and

The second feature of derivatives that should be Metaligesellschaft. But, as the Dresser Industries

kept in mind is the "linearity" or "nonlinearity" of and Caterpillar examples show, this head-in-the-

the contracts. Futures and forwards are essentially sand approach has costs as well. Nor can risk man-

linear contracts: for every dollar the company gains agement simply be handed off to the financial staff.

when the underlying variable moves in one direc- That approach can lead to poor coordination with

tion by 10%, it loses a dollar when the underlying overall corporate strategy and a patchwork of de-

variahle moves in the other direction by 10%. By rivatives trades that may, when taken together, re-

contrast, options are nonlinear in that they allow duce overall corporate value. Instead, it's critical

the company to put a floor on its losses without for a company to devise a risk-management strate-

having to give up the potential for gains. If there is gy that is based on good investments and is aligned

a minimum amount of investment a company needs with its hroader corporate objectives.

to maintain, options can allow it to lock in the nec- 1. The siuily, rupurtL-d in Derivatives: Practices and Principles, was con-

essary cash. At the same time, they provide the ducted by the Group of Thirty, an independent Study group in Washing-

flexibility to increase investment in good times. ton, D.C., made up lit economists, bankers, and policymakers.

2. A more technical article on this suhject, "Risk Management: Coordinat-

Again, the decision of which contract to use ing Corporate Investment and Financing Policies," was pahlished hy the au-

should he driven hy the objective of aligning the de- thors in th\: lournul t>( [•imincc. vol.48, 199^1, p. 1629.

mand for funds with the supply of internal funds. A .1. This view has been advanced in an influential series of papers hy Stew-

art C. Myers of MIT's Sloan Schoul ot Management: "The Determinants

skillful financial engineer may be good at pricing of Corporate Borrowing," loiirmil of Financial Economics, vol. 4, 1977,

intricate financial contracts, but this alone docs not p. 147; "CurporatL- Financing and Investment Decisions When Firms Have

Information That Investors Do Not Have," coauthored with Nicholas

indicate which types of contracts fit best with a Majluf, loiirnci! of Finnncia! Economics, vol. 13, 1984, p, 187, antJ "The

company's risk-management strategy. Capita] Structure Puzzle," louinii! of Finance, vol.39, 1984, p. S75.

An important corollary to this point is that it 4. See, for example, leffrey MacKie-Mason, "Do Firms Care Who Provides

Their Financing?" in Asymmetric Information, Corportitt: Finance, and

probably makes good sense to stay away from the Investment, ed. R. Clenn Hubbard (Chicago: University of Chicago Press,

most exotic, customized hedging instruments un- 1990), p. 63,

less there is a very clear investment-side justifica- 5. Paul Asquith and David Mullins, "Equity Issues and Offering Dilu-

tion," Journal of Finuncidl Economics, vol. IS, 1986, p. 61.

tion for their use. Dealers make more profit selling

6. See, for example, Steven Fazzari, R. Glenn Hubhard, and Bruce

cutting-edge instruments, for which competition is Petersen, "Financing Constraints and Corporate Investment," Broakmgs

less intense. And each additional dollar of profit go- Papers on Economic Activity, no. 1, 1988, p, 141.

ing to the dealer is a dollar less of value availahle to Reprint 94604

102 HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW Novcmher-Decemher 1994

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Account Statement From 1 Sep 2020 To 6 Oct 2020: TXN Date Value Date Description Ref No./Cheque No. Debit Credit BalanceDocument2 pagesAccount Statement From 1 Sep 2020 To 6 Oct 2020: TXN Date Value Date Description Ref No./Cheque No. Debit Credit BalancePAWAN SHARMANo ratings yet

- 12 Asian Cathay Finance V Sps Gravador and de VeraDocument9 pages12 Asian Cathay Finance V Sps Gravador and de VeraAnne VallaritNo ratings yet

- Vinati OrganicsDocument6 pagesVinati OrganicsNeha NehaNo ratings yet

- Consolidated Financial Statements Dec 312012Document60 pagesConsolidated Financial Statements Dec 312012Inamullah KhanNo ratings yet

- Buffalo Accounting Go-Live ChecklistDocument16 pagesBuffalo Accounting Go-Live ChecklistThach DoanNo ratings yet

- A Company Is An Artificial Person Created by LawDocument5 pagesA Company Is An Artificial Person Created by LawNeelabhNo ratings yet

- Partnership Agreement (Short Form)Document2 pagesPartnership Agreement (Short Form)Legal Forms91% (11)

- 24.4 SebiDocument30 pages24.4 SebijashuramuNo ratings yet

- A Study On Lending Practices of RDCC Bank, SindhanurDocument60 pagesA Study On Lending Practices of RDCC Bank, SindhanurHasan shaikhNo ratings yet

- Letters of Credit NotesDocument3 pagesLetters of Credit NotesattorneyNo ratings yet

- Portfolio Management ServicesDocument24 pagesPortfolio Management ServicesASHI100% (5)

- 1109021 (1)Document1 page1109021 (1)Cms Stl CmsNo ratings yet

- Reverse Takeovers - An ExplanationDocument6 pagesReverse Takeovers - An ExplanationMohsin AijazNo ratings yet

- Effects of InflationDocument3 pagesEffects of InflationonenumbNo ratings yet

- Psak 72 10 Minutes PDFDocument2 pagesPsak 72 10 Minutes PDFMentari AndiniNo ratings yet

- A Boost For Your Career in Finance: Benefits IncludeDocument2 pagesA Boost For Your Career in Finance: Benefits IncludeSarthak ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Central Bank: The Guardian of CurrencyDocument6 pagesCentral Bank: The Guardian of CurrencyBe YourselfNo ratings yet

- Salary Packaging - Smart SalaryDocument9 pagesSalary Packaging - Smart SalaryraogongfuNo ratings yet

- Intermediate Accounting 8Th Edition Spiceland Test Bank Full Chapter PDFDocument67 pagesIntermediate Accounting 8Th Edition Spiceland Test Bank Full Chapter PDFchanelleeymanvip100% (11)

- MCX Deepens Its Footprint in The GIFT City (Company Update)Document3 pagesMCX Deepens Its Footprint in The GIFT City (Company Update)Shyam SunderNo ratings yet

- Exchange Rate Exposure and Its Determinants Evidence From Indian FirmsDocument16 pagesExchange Rate Exposure and Its Determinants Evidence From Indian Firmsswapnil tyagiNo ratings yet

- ZTBL Internship ReportDocument33 pagesZTBL Internship Reportmuhammad waseemNo ratings yet

- Nike CaseDocument10 pagesNike CaseDanielle Saavedra0% (1)

- November 2019Document4 pagesNovember 2019Astrid MeloNo ratings yet

- LESSON 8 - Purpose of BanksDocument5 pagesLESSON 8 - Purpose of BanksChirag HablaniNo ratings yet

- Risk Assessment Worksheet BlankDocument5 pagesRisk Assessment Worksheet BlankisolongNo ratings yet

- Blackbook Project On Merchant BankingDocument66 pagesBlackbook Project On Merchant BankingElton Andrade75% (12)

- Negotiable InstrumentsQ&ADocument11 pagesNegotiable InstrumentsQ&AMelgen100% (1)

- Investment Arbitration and Country Risk 1711783556Document28 pagesInvestment Arbitration and Country Risk 17117835568nqcpq9tq9No ratings yet