Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Goldberg GLBT Family Studies 2006 PDF

Uploaded by

FSony0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

1 views16 pagesOriginal Title

Goldberg GLBT Family Studies 2006.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

1 views16 pagesGoldberg GLBT Family Studies 2006 PDF

Uploaded by

FSonyCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 16

The Transition to Parenthood

for Lesbian Couples

Abbie E. Goldberg

ABSTRACT. Wi

with older childre

bian couples is se current study examines aspects of the transi

tion to parenthood experience for 29

udy explores aspects of couples d

there is a slowly growing literature on lesbians

pe), per-

Support across the transition to parenthood, and avail-

ability and use of legal safeguards (such as wills, powers of attorney, and

coparent adoptions by nonbiological mothers). Future studies should ex-

plore how single lesbians manage the transition to parenthood, Research

on lesbians and gay men who are e

also needed. (Aricl copies availab

Livery Service: 1-800-HAWORTH, E-mail address: Website: © 2006 by The Haworth Pres,

dh, All rights reserved]

KEYWORDS. Lesbian mothers, lesbian couples, tran

hood, parenthood decision, alternative insemination, leg

See rarer

Abbie E. Goldberg, MS, is ie Department of Psychology, Univer-

sity of Massachusetts, Amherst ibbieg @psych.umass.edu).

This research was conducted under the Roy Serivner Disseitation Award Grant

(2002), awarded by the American Psychological Foui and the Jessie Bernard

‘Award (2002), awarded by the National Couneil on Family Relations.

Journal of GLBT Family Studies, Vol. 2(1) 2006

Available online at hutp.//ww-haworthpress.com/web/GLBTF

‘© 2006 by The Haworth Press, Inc, All rights reserved

dois10.1300/7461 v0zn01_02 B

i JOURNAL OF GLBT FAMILY STUDIES

‘The transition to parenthood for lesbian couples is aneglected yet im-

portant area of research. Understanding the experience of lesbian

women as they become parents is increasingly significant given that be-

tween 1.5 and 5 million lesbians are currently raising children (Allen &

1993; Patterson, 199Sa). Some of these women be-

ontext of heterosexual unions; however, since the

1980s, increased access to donor insemination has allowed many lesbi-

ans to pursue parenthood, resulting in a lesbian baby boom and a conse-

quent increase in the number of children born to lesbian couples

(Gartrell, Harnilton, Banks, Mosbacher, Reed, Sparks, & Bishop, 1996;

Gartrell, Banks, Hamilton, Reed, Bishop, & Rodas, 1996; Gartrel,

Banks, Reed, Hamilton, Rodas, & Deck, 2000; Patterson, 1992).

Although several clinicians have written books based on their experi-

ences working with lesbian women and couples who are considering

parenthood (e.g., Martin, 1993; Pies, 1987), very little empirical re-

ines lesbian couples’ transition to parenthood experience

1996, 1999, 2000). We know very little about the experi-

n couples as they prepare for and take on the role of par-

ent although scholars of family diversity (e.g., Allen, Fine, and Demo,

2000) have underlined this area as one of growing importance.

There is, however, a slowly growing body of literature on lesbian

children (Patterson, 192; Tasker & Golombok, 1997) as

number of studies that have focuse

ples without children (Kurdek, 1993, 1994),

much of the research on lesbi

well-being but only insofar as to compare these women’s mental

that of heterosexual mothers. Several studies have found no differ-

logical health of lesbian and heterosexual

(Falk, 1989; McNeil, Rienzi, & Kposow: 1992, 1997)

vith others reporting enhanced psychologi

areas of self-confidence and sel

Some research

that optimize mental be

pears that openness about one’s sexu:

hanced well-being among both lesbian parents (Rand, Graham, &

Rawlin; ,yala & Coleman, 2000; Mor-

ris, Waldo, & Rothblum, 2001). Soci

» Rot

the factors or conditions

ind mother’

Abbie E. Goldberg Is

Coleman, 2000; Oetjen & Rothblum, 2000) and friends (Oetjen &

Rothblum, 2000) also appear to reduce lesbians’ risk for depression.

n couples” relationship quality has also been the subject of re-

search. In general, lesbians and gay men report high relationship satis-

faction relative to norms for relationship satisfaction for heterosexual

‘couples (Patterson, 1995a; Peplau & Cochran, 1990). Identified corre

lates of relationship quality for lesbian couples include feelings of hav-

ing equal power in the relationship, sharing decision-making, and

placing high value on the relationship (Kurdek, 1994, 1995; Peplau,

Padesky, & Hamilton, 1983). Interestingly, although lesbian couples

value egalitarian child rearing (Dunne, 1998, 2000), only about half of

lesbian couples studied appear to have achieved it (e.g., Brewaeys,

Devroey, Helmerhorst, van Hall, & Ponjaert, 1995; Wendlan«

Hill, 1996), There is evidence that when children are young,

mothers are somewhat more involved in child care and nor

mothers spend more time in paid employment (Patterson,

equal division of labor appears to be in both the parents” and,

vestigation o

were conceived by donor insemination and which includes data

before couples have given birth. The researchers project that they

interview these f

over a 25-year period.

is research has yielded three publications (Gi

descriptive

pregnancy preferences and mot

tions, and social support. Results revealed that the NLLFS samp!

igely Caucasian, relatively well-educated, and, at the time of the

terview, women in couples had been together for a mean of 6 years.

16 JOURNAL OF GLBT FAMILY STUDIES | Abbie E. Goldberg

When asked aboi

‘heir preferences regarding alternative insemination, gether at this time point, 29 were sharing child rearing equally. In 17

47% of the sample preferred an unknown sperm donor, 45% preferred a couples, biological mothers did more, and in four couples, nonbio.

known donor, and 8% reported that they had no preference." As a whole, logical mothers performed a greater proportion of child c:

Tyomen had strong support networks: most women were in regular con family suppor, 14% of birthmothers in continuous relationships saic

tact with their families of origin, and most (78%) expected at least some their parents did not acknowledge their partners as co-mothers, More-

people in their family to accept their child. Moreover, the majority of over, 17% of biological mothers and 13% of nonbiologi

Women reported having a bestfriend outside of the family, and most ex-

pected that existing friendships wo

would not change (27%) after the birth,

In the

either enhanced (35%) or

idy was designed to build on Gartrell and her col-

iffers from their study in several fundamental

ind most importantly, a criterion for the current study was

men were transitioning to parenthood for the first time. The

colleagues report data from the

n Were tWo years old. Foci of

intervie Parenting issues, legal supports, and so-

support. Most children had been born vaginally (68%), and most NLLFS sample included women who were sing ie ee

covered by health insurance (94%). Seventy-five percent of the third time; only 62% of prospective birth mothers were pregnant for the

reported sharing child care equal time. Second, al requirements of the t

Id care was shared but the biological mother was considered fisttime. Second, two ad relatcashipe ond at eee Marea at

-three percent of children carried both moth- eae

: we birth of the child—were not criteria for in-

ae Mosteouining 57% eee Clusion in the NLLFS. Third, the current study is focused on a short pe.

familieshad wills sod Soe owers of storney fort iod of time-a month before to three months after the arrival of

gible nonbiologieal mothers (meters 's first child. In the NLLFS, there was no standard time for the

women’s

where coparent adopt first interview (women were interviewed at some point during the pro.

children, With regard to soci

ess of insemination or during the pregnancy) and the second inter iew

ga 1 vy

child enhanced their relationship with their own parents, Contact with was not conducted ae the child was 2 years old, In ad

‘one's own parents had increased for 55% of women, and 77% reported credit, the NLLFS is far more long-term,

that ther parents were very excited about their grand Thus, the cufrent study included 29 couples that were preparing to

ol mothers tended to rate their own parents as closer to the target ive birth to their first child via alternative insemination. (The study

tude couples that were preparing to adopt their first

however, because of the small number of adoptive couples that

Obtained, their data are not presented here.) Both part-

iewed before the birth of their first child (in the last

1 month before the due date) and 3 months after

baby was born, Effort was made to recruit participants who were

Verse with respect to age and geography, and, to the extent possible,

and social cla

iper come from a larger study that assessed

child than nonbiological mothers rated their own parents. With regard

to support from friends, a quarter of women reported the loss of some

friendships, often with lesbians who were not parents themselves,

Finally, in their (2000) paper, Gartrell and her colleagues report on a

number of domains including women’s rela parenting experi-

ences, and social support. By % of the o:

couples had divorced (15% of divorces oc

Time 3). Child custody was shared in 10 0

mothers retained sole custod: rimary custody

mothers were more likely to have sole or primary custody if the ing the deci ing process regarding

nonbiological mother had not officially adopted the child indicating the employment, social support, the division of labor

power of coparent adoptions to increase the likelihood of shared cus. important to note that

{ody in the case of relationship termination among lesbian couples. apers using these data are currently under review for pul

‘With regard to parenting, of the 50 original couples who were still to. 1) Goldberg and Sayer's paper examines the relatio

You might also like

- Seu Amor É Grosso DemaisDocument16 pagesSeu Amor É Grosso DemaisFSonyNo ratings yet

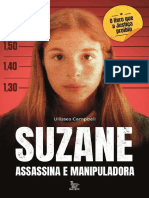

- Suzane Assassina e Manipulador Ebooksdemais PDFDocument239 pagesSuzane Assassina e Manipulador Ebooksdemais PDFJessica Souza95% (40)

- Genealogias Abjetas o Que Tem de Queer o PDFDocument3,669 pagesGenealogias Abjetas o Que Tem de Queer o PDFFSony100% (1)

- Psicologia PDFDocument116 pagesPsicologia PDFFSonyNo ratings yet

- (Livro) Aleister Crowley - O Livro Das MentirasDocument188 pages(Livro) Aleister Crowley - O Livro Das MentirasFSonyNo ratings yet

- Idade MediaDocument12 pagesIdade MediaFSonyNo ratings yet

- (Artigo) Agnes B Curry - The-Metaphysical-Basis-of-Sexuality PDFDocument17 pages(Artigo) Agnes B Curry - The-Metaphysical-Basis-of-Sexuality PDFFSonyNo ratings yet

- Quadros de Guerra PDFDocument3 pagesQuadros de Guerra PDFFSonyNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)