Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Procannmeetasil 103 1 0403

Uploaded by

Arjun SOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Procannmeetasil 103 1 0403

Uploaded by

Arjun SCopyright:

Available Formats

Lawmaking by the ICJ and Other International Courts

Author(s): Thomas Buergenthal

Source: Proceedings of the Annual Meeting (American Society of International Law) , Vol.

103, International Law As Law (2009), pp. 403-406

Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the American Society of

International Law

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5305/procannmeetasil.103.1.0403

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Cambridge University Press and American Society of International Law are collaborating with

JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Proceedings of the Annual Meeting (American

Society of International Law)

This content downloaded from

123.63.228.146 on Mon, 11 Mar 2019 12:17:01 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

International Law as Law at the International Court of Justice 403

factor that gives the jurisprudence of the ICJ a special place of respect, even in the absence

of a formal hierarchical order.

Lawmaking by the ICJ and Other International Courts

By Thomas Buergenthal*

Although the proliferation of international courts as a subject has received considerable

attention in recent years, the same has not been true of the ever more important role these

courts play in the international lawmaking process. This is the topic I propose to deal with

this afternoon, with special emphasis on the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

When Article 38 of the current statute of the ICJ was adopted, it was the only permanent

international court in existence. That, of course, was also true with regard to the comparable

provision of the statute of the Permanent Court of International Justice. After identifying the

three principal sources of international law—international conventions, custom, and general

principles of law—Article 38 declares that, subject to the provisions of Article 59 of the

Statute, the subsidiary means for the determination of rules of law are ‘‘judicial decisions

and the teachings of the most highly qualified publicists of the various nations.’’ Thus, while

under Article 59 decisions of the ICJ are binding between the parties to a case, judicial

decisions generally, whether rendered by national or international courts, merely serve as

‘‘subsidiary means for the determination of rules of law.’’

The world has changed rather dramatically since the ICJ Statute was adopted. For one

thing, the ICJ is no longer the only international court in existence. It has been joined by a

growing number of important international and regional courts and tribunals, among them

the International Criminal Court, Law of the Sea Tribunal, European Court of Justice, three

regional human rights tribunals, and various ad hoc international criminal tribunals, including

the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the International

Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. During the past decade, furthermore, more cases have been

referred to the ICJ than ever before, and more keep coming. These cases deal with an ever

greater number of international law subjects than in the past. In addition to its traditional

fare of territorial and maritime disputes, the Court is today increasingly being called upon

to decide a whole range of disputes, including cases concerning the illegal exploitation of

natural resources, human rights and humanitarian law, the use of force, treaty interpretation,

self-determination, consular rights, different types of immunities, international environmental

law, state responsibility, the law of international organizations, and so on. The jurisprudence

which these cases generate, together with important earlier ICJ decisions, cover an ever

broader range of international law topics.

And as the number of new cases grows, so does the international law the Court is called

upon to interpret and apply. In the process, it clarifies existing law and of necessity makes

new law, not with the broad brush strokes generally employed by legislatures, but by what

might be called normative accretion. Other international and regional courts also render more

and more judgments in their fields of judicial competence, thus further expanding the existing

corpus of international law.

It should, therefore, be asked what the legal effect of this case law is. It is clear, of course,

that the doctrine of stare decisis is not part of international law. For states not parties to a

case, judgments of the ICJ and of some other international courts are formally not lawmaking

*

Judge, International Court of Justice.

This content downloaded from

123.63.228.146 on Mon, 11 M on Thu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

404 ASIL Proceedings, 2009

in character in the sense in which decisions of Common Law courts are binding precedents

within their respective jurisdictions.

But, what of the practical legal effect of such judgments? What is the significance of the

fact that the ICJ is the principal judicial organ of the United Nations? Do ICJ decisions have

a special normative effect on the international plane as a result of its status, even though

Article 38 speaks of judicial decisions in general and does not confer on decisions of the

ICJ a hierarchic supremacy vis-à-vis judgments of other international courts? Of course, in

a formal legal sense ICJ decisions do not enjoy such a preferred status. But does this answer

not overlook the normative effect which states, international organizations, international

arbitral tribunals, and international lawyers—in short, the international community gener-

ally—increasingly attribute to decisions of the ICJ, precisely because it is the principal

judicial organ of the UN and because its decisions have over the years gained legitimacy

and respect commensurate with this special status?

It is therefore not surprising that when it comes to determining what the relevant interna-

tional law rule is, a decision by the ICJ will today, in general, be treated by the international

community as the most authoritative statement on the subject and accepted as the law. Note,

for example, how closely the International Law Commission followed the jurisprudence of

the Court in drafting its Articles on State Responsibility and how frequently this jurisprudence

is invoked as law in diplomatic correspondence and in decisions of international arbitral

tribunals, probably more so than the traditional sources of international law—particularly

custom and general principles—that have not been authenticated or validated by an ICJ

judgment.

It is possible, of course, to view this role of the ICJ merely as reflecting its traditional

function as a ‘‘subsidiary means for the determination of rules of law’’ within the meaning

of Article 38(1)(d) of the ICJ Statute. But this conclusion would miss the significant transfor-

mation that international law as a legal system has undergone and is undergoing as a result,

first, of the increasing number of cases that come to the ICJ, which reflects an ever wider

acceptance of the legitimacy of its expanding judicial role and lawmaking authority and,

second, the comparable lawmaking role that other international and regional courts perform

within their respective spheres of judicial competence.

The ICJ, together with the other existing international courts, make up a rapidly evolving

international judicial system that continues to expand and gain in importance because states

resort to it increasingly to resolve their disputes and because they invoke its jurisprudence

as law with ever greater frequency. As more and more disputes between states are resolved

by international courts, states rely on the decisions of these courts more than ever before to

validate their international legal claims. The lengthy arguments advanced in the past by

governments to prove that a practice has become customary international law, for example,

or that a certain interpretation of a treaty is the correct one, are increasingly giving way to

the simple citation of one or the other ICJ judgment or decision of another international

court as the governing law.

It can be argued, of course, that recourse to these decisions is merely a shorthand form

of citing them as evidence of what the law is rather than as law in its own right—the

subsidiary means argument—but the reality is different. The existence of a functioning

international judicial system with the ICJ at its informal apex, increasingly transforms these

decisions, as a practical matter, into directly applicable law.

Here, it is worth recalling that despite the fact that under Article 59 of the Statute decisions

of the ICJ bind only the parties to the case, the Court treats all its decisions as judicial

This content downloaded from

123.63.228.146 on Mon, 11 Mar 2019 12:17:01 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

International Law as Law at the International Court of Justice 405

precedents from which it will rarely depart, and then only in special circumstances. The ICJ

made that point most recently in Croatia v. Serbia, when it declared that ‘‘to the extent that

the decisions contain findings of law, the Court will treat them as all previous decisions:

that is to say that, while those decisions are in no way binding on the Court, it will not

depart from its settled jurisprudence unless it finds very particular reasons to do so.’’1 This

is not a message about applicable law that is likely be lost on counsel appearing before the

Court or, for that matter, on government legal advisers generally.

The practice of international courts also indicates that they increasingly cite not only their

own decisions but also judgments of their sister institutions, the way American courts cite

decisions from other jurisdictions. While obviously not binding precedents as between them,

these decisions are treated as persuasive authority to be relied upon or not depending upon

the soundness of their reasoning or analysis. That, for example, is how the ICJ looked to

the decisions of the ICTY in the recent Genocide case and how the Inter-American Court

of Human Rights draws on decisions of the European Court of Human Rights and those of

the ICJ. Similar practice can be observed in the context of Permanent Court of Arbitration

and International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes arbitrations, for example,

where ICJ judgments are routinely relied upon as relevant law in the awards rendered by

the panels of arbitrators. Comparable examples abound throughout the international judicial

system, which includes the case law of international administrative tribunals and that of the

United Nations human rights treaty bodies. A particularly telling example is the reference

of the ICJ to the case law of the UN Human Rights Committee in addressing the question

of the extraterritorial application of Article 2(1) of the International Covenant on Civil and

Political Rights.2 In short, what we have here is international judicial cross-fertilization

that enriches and strengthens contemporary international law. I believe that the lawmaking

significance of this phenomenon remains to be fully appreciated in the teaching of contempo-

rary international law.

Also, not to be overlooked in understanding the importance of this cross-fertilization

process is the normative effect international court decisions are increasingly having on

judgments of national courts. Decisions of the European Court of Human Rights, for example,

are routinely followed by national courts of the States Parties to the European Convention.

Decisions of the Inter-American Court on Human Rights are beginning to have a similar

impact on judgments of national courts in the Americas. ICJ decisions tend also to be followed

by many national courts when called to apply international law, but not Texas, of course,

or the U.S. Supreme Court.

The international judicial system in existence today is not hierarchically integrated in that

no court in the system is formally superior to any of the others. I am not sure that this is

necessarily detrimental to the development of international law. For, to the extent that it

permits greater lawmaking creativity within the international judicial system and by courts

comprising that system, it is likely to strengthen international law. At the same time, let us

not forget that there exists an informal hierarchy which comes into play when one or the

other of these international courts finds it necessary to apply general international law in the

exercise of its functions. In such situations, it will in general look first to the jurisprudence

of the ICJ.

1

Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Bosnia and

Herzegovina v. Serbia and Montenegro), Judgment (Feb. 26, 2007).

2

Armed Activities on the Territory of the Congo (Congo v. Uganda), 2000 ICJ Rep. 111 (July 1).

This content downloaded from

123.63.228.146 on Mon, 11 Mar 2019 12:17:01 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

406 ASIL Proceedings, 2009

Moreover, as we have already seen in the recent Genocide Case and in some other cases,

the ICJ is also beginning to draw on the jurisprudence of other international courts. The

absence of an international legislature with general lawmaking power, and the fact that

lawmaking treaties tend to address only a limited number of subjects, means that the ICJ

and the other courts comprising the international judicial system play an ever more important

lawmaking role. This emerging process increasingly resembles the lawmaking role that courts

play in the Anglo-American legal system, frequently relying as authority on a mix of judicial

decisions, both binding and not binding within a particular jurisdiction. A similar type of

judicial cross-fertilization and lawmaking is now also being practiced within the international

judicial system. While this practice does not find expression in Article 38 of the Court’s

statute, it reflects the contemporary reality and the growing importance of international

judicial lawmaking as well as the needs of the international community. Today, as a result,

international law is a more vibrant and mature legal system than ever before, and that is

what makes it more fun to be a part of.

Remarks by Bruno Simma*

Judge Bruno Simma primarily discussed the process, and likelihood, of institutional change

at the International Court of Justice (ICJ). More specifically, he predicted that the Court

would undergo minimal change in the coming years, despite various proposals currently up

for review, due to issues of institutional resistance. As he put it, courts are generally sedentary

institutions and tend toward preserving the status quo, as evidenced by the fact that the rules

governing the ICJ have hardly changed since their original drafting in the early 1920s.

Nonetheless, Judge Simma observed that the Court has been successful in implementing

several incremental changes to promote efficiency such as restricting the length of briefs

and imposing time limits on oral proceedings. Moreover, efforts to increase the number of

law clerks at the ICJ and to improve coordination with other international courts have been

important developments. He further explained that renewed attention needs to be directed

at reforming the process of asking questions before the Court and reevaluating the use of

chamber proceedings.

*

Judge, International Court of Justice.

This content downloaded from

123.63.228.146 on Mon, 11 Mar 2019 12:17:01 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- The International Court of Justice: An Arbitral Tribunal or a Judicial Body?From EverandThe International Court of Justice: An Arbitral Tribunal or a Judicial Body?No ratings yet

- Damodaram Sanjivayya National Law University Visakhapatnam, A.P., IndiaDocument23 pagesDamodaram Sanjivayya National Law University Visakhapatnam, A.P., IndiaArthi GaddipatiNo ratings yet

- Journal of International Dispute SettlementDocument19 pagesJournal of International Dispute SettlementaliNo ratings yet

- General Principles of Law Recognised by Civilised StatesDocument7 pagesGeneral Principles of Law Recognised by Civilised StatesSangeeta SinghNo ratings yet

- Sources of International LawDocument6 pagesSources of International Lawmoropant tambe0% (1)

- Sources of International LawDocument6 pagesSources of International Lawmoropant tambeNo ratings yet

- American Society of International Law The American Journal of International LawDocument10 pagesAmerican Society of International Law The American Journal of International LawRISHINo ratings yet

- Akash 189 PIL - Merged-Pages-DeletedDocument26 pagesAkash 189 PIL - Merged-Pages-DeletedCharu LataNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Source of International Law (PIL)Document9 pagesContemporary Source of International Law (PIL)Rahul manglaNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Source of International Law (PIL)Document9 pagesContemporary Source of International Law (PIL)Rahul manglaNo ratings yet

- Enforcement of International Judicial DecisionsDocument189 pagesEnforcement of International Judicial DecisionsmanishdgNo ratings yet

- International Law AssignmentDocument11 pagesInternational Law AssignmentUjjwal MishraNo ratings yet

- PIL Anuj 021 Assignment PDFDocument19 pagesPIL Anuj 021 Assignment PDFsajidpathaan1No ratings yet

- Project - Public International LawDocument18 pagesProject - Public International LawAparna SinghNo ratings yet

- Sources of Human RightsDocument5 pagesSources of Human RightsSebin JamesNo ratings yet

- Photography by JazbaDocument4 pagesPhotography by JazbaUxair ShafiqNo ratings yet

- DR PilDocument20 pagesDR PilNamanNo ratings yet

- PIL Docs SahilDocument18 pagesPIL Docs SahilSinghNo ratings yet

- Sources of International Law - Written AssignmentDocument11 pagesSources of International Law - Written AssignmentAiman HafizNo ratings yet

- General Principles of International Law Recognised by Civilised StatesDocument6 pagesGeneral Principles of International Law Recognised by Civilised StatesNavdeep Birla100% (1)

- International Law SeminarDocument4 pagesInternational Law Seminarmahek agarwalNo ratings yet

- Project - Public International LawDocument16 pagesProject - Public International LawAparna SinghNo ratings yet

- Cambridge University Press The American Journal of International LawDocument22 pagesCambridge University Press The American Journal of International LawMamatha RangaswamyNo ratings yet

- Greenwood Outline PDFDocument5 pagesGreenwood Outline PDFCharmaine Reyes FabellaNo ratings yet

- The Use of Precedent by International Judges and ArbitratorsDocument19 pagesThe Use of Precedent by International Judges and Arbitratorsnivartana selvamNo ratings yet

- Iura Novit Curia and Due Process PDFDocument19 pagesIura Novit Curia and Due Process PDFIgorRRSSNo ratings yet

- Describe The Principles of General International LawDocument2 pagesDescribe The Principles of General International LawshafeeqmohaNo ratings yet

- Source of InternatiDocument3 pagesSource of InternatiHabtamu GabisaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Discussion QuestionsDocument4 pagesChapter 2 Discussion Questionslexyjay1980No ratings yet

- Chapter On ICJDocument31 pagesChapter On ICJSovanrangsey KongNo ratings yet

- Custom As A Source of International Law PDFDocument14 pagesCustom As A Source of International Law PDFMeenakshi SharmaNo ratings yet

- Sources of International Law11Document12 pagesSources of International Law11shubhamNo ratings yet

- The Sources of International Law (I)Document11 pagesThe Sources of International Law (I)100453151No ratings yet

- Final Pil Notes - AnshulDocument142 pagesFinal Pil Notes - AnshulSaloni MishraNo ratings yet

- Public International Law ProjectDocument10 pagesPublic International Law ProjectJenniferNo ratings yet

- Judicial Intervention in International Arbitration: TH THDocument26 pagesJudicial Intervention in International Arbitration: TH THtayyaba redaNo ratings yet

- Notes On Law of International InstitutionsDocument22 pagesNotes On Law of International InstitutionsAdvika PhotumsettyNo ratings yet

- Conflicts of LawDocument22 pagesConflicts of LawHijabwear BizNo ratings yet

- Public Internaitonal Law Questionss and AnswersDocument18 pagesPublic Internaitonal Law Questionss and AnswersFaye Cience BoholNo ratings yet

- Elaboration On Article 38 of The Statute of The International Court of JusticeDocument7 pagesElaboration On Article 38 of The Statute of The International Court of JusticeSabella Clara100% (1)

- Symbiosis Law School, Nagpur Academic Year 2021-22 Batch 2019-24 Ba/Bba. LLB Semester-V Subject - Public International LawDocument6 pagesSymbiosis Law School, Nagpur Academic Year 2021-22 Batch 2019-24 Ba/Bba. LLB Semester-V Subject - Public International Lawgeethu sachithanandNo ratings yet

- GUILLAUME Gilbert. The Use of Precedent by International Judges and Arbitrator 2011Document19 pagesGUILLAUME Gilbert. The Use of Precedent by International Judges and Arbitrator 2011Ioana NustiuNo ratings yet

- Multiple Courts Bad NCDocument15 pagesMultiple Courts Bad NCCedric ZhouNo ratings yet

- Courts in International LawDocument1 pageCourts in International LawSandra SimNo ratings yet

- International Law - Ian Brownlie: Part I - Preliminary Topics 1. Sources of The LawDocument17 pagesInternational Law - Ian Brownlie: Part I - Preliminary Topics 1. Sources of The LawAmadeus CachiaNo ratings yet

- Customary International Law and Treaties - A Critical Analysis.Document8 pagesCustomary International Law and Treaties - A Critical Analysis.Jananthan Thavarajah100% (5)

- Customary International Law and Treaties A Critical AnalysisDocument9 pagesCustomary International Law and Treaties A Critical AnalysisAniket RajNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Sources of The International LawDocument10 pagesIntroduction To The Sources of The International Lawvaibhav katochNo ratings yet

- Administrator,+unblj v60 Forum02Document23 pagesAdministrator,+unblj v60 Forum02VAISHNAVI RASTOGI 19113047No ratings yet

- CES by Amandeep DrallDocument9 pagesCES by Amandeep DrallAman SinghNo ratings yet

- Group 3 - International LawDocument14 pagesGroup 3 - International LawEdem EdysonNo ratings yet

- PIL Project (1884)Document10 pagesPIL Project (1884)fathimaliyanacm1884No ratings yet

- Case Summaries PIL 1Document5 pagesCase Summaries PIL 1yawizzy bNo ratings yet

- Sources of International Space Law - Jaku and FreelandDocument19 pagesSources of International Space Law - Jaku and FreelandIsha SenNo ratings yet

- Hat Is Public International LawDocument74 pagesHat Is Public International LawAsraleah Mac DeeNo ratings yet

- Guido Acquaviva e Fausto Pocar - Stare DecisisDocument10 pagesGuido Acquaviva e Fausto Pocar - Stare DecisisPablo AlflenNo ratings yet

- 2.PIL-Intr OPIL Problems and Process 2 Sources of International Law Provenance and Problems KKDocument16 pages2.PIL-Intr OPIL Problems and Process 2 Sources of International Law Provenance and Problems KKEtuna MerabishviliNo ratings yet

- Ii. Sources of International Law: Restatement (Third) of Foreign Relations Law of The United StatesDocument5 pagesIi. Sources of International Law: Restatement (Third) of Foreign Relations Law of The United StatesMuji JaafarNo ratings yet

- Sources of International Law: Pratiksha Sharma Sem-7, Roll No - 305/20 Sec - FDocument19 pagesSources of International Law: Pratiksha Sharma Sem-7, Roll No - 305/20 Sec - FRaaghav SapraNo ratings yet

- IA - Enforcement of Awards Set Aside GuilardDocument31 pagesIA - Enforcement of Awards Set Aside GuilardMarta BokuchavaNo ratings yet

- 2015RDocument44 pages2015RArjun S100% (1)

- The International Unification of Air LawDocument26 pagesThe International Unification of Air LawArjun S100% (1)

- Lily Thomas and Ors Vs Union of India UOI and Ors 0927s000503COM506930Document24 pagesLily Thomas and Ors Vs Union of India UOI and Ors 0927s000503COM506930Arjun SNo ratings yet

- The Relevance of The International Court of Justice in International LawDocument8 pagesThe Relevance of The International Court of Justice in International LawArjun SNo ratings yet

- Strategic Analysis of Raymond App. Ltd.Document8 pagesStrategic Analysis of Raymond App. Ltd.thegr81pary83% (6)

- 07 Chapter 3Document12 pages07 Chapter 3Arjun SNo ratings yet

- Applications On Website For INTSPDocument1 pageApplications On Website For INTSPArjun SNo ratings yet

- Financial ManagementDocument3 pagesFinancial ManagementArjun SNo ratings yet

- Right To Peace As A Human Right: Rakesh Kumar SinghDocument9 pagesRight To Peace As A Human Right: Rakesh Kumar SinghArjun SNo ratings yet

- Applications On Website For INTSPDocument1 pageApplications On Website For INTSPArjun SNo ratings yet

- ICJ Guide JMCMUN GenocideDocument12 pagesICJ Guide JMCMUN GenocidesunidhiNo ratings yet

- Team Best Memorial Petitioner Nalsar Public International Sanikasunil1552 Nualsacin 20240122 082206 1 20Document20 pagesTeam Best Memorial Petitioner Nalsar Public International Sanikasunil1552 Nualsacin 20240122 082206 1 20sanikasunil1552No ratings yet

- Anglo French PDFDocument14 pagesAnglo French PDFRAINBOW AVALANCHENo ratings yet

- Lesson 4 Lecture NotesDocument5 pagesLesson 4 Lecture NotesJohn Mark CabillarNo ratings yet

- Powers-and-Functions-of-the-Security-Council (Bacsal & Flores)Document13 pagesPowers-and-Functions-of-the-Security-Council (Bacsal & Flores)DANICA FLORESNo ratings yet

- 2013 Ad MU PIL SyllabusDocument10 pages2013 Ad MU PIL SyllabusowenNo ratings yet

- Duke University School of LawDocument35 pagesDuke University School of LawAleePandoSolanoNo ratings yet

- Nature, Origin and Basis of International LawDocument18 pagesNature, Origin and Basis of International LawTahir WagganNo ratings yet

- PIL Midterm TANYA PDFDocument28 pagesPIL Midterm TANYA PDFJillandroNo ratings yet

- (The Collected Courses of The Academy of European Law 13,1) Christian Tomuschat - Human Rights - Between Idealism and Realism-Oxford University Press (2009)Document465 pages(The Collected Courses of The Academy of European Law 13,1) Christian Tomuschat - Human Rights - Between Idealism and Realism-Oxford University Press (2009)Saint NarcissusNo ratings yet

- The Contemporary Global Governance PPT 4Document10 pagesThe Contemporary Global Governance PPT 4Cyanide048100% (1)

- United NationsDocument155 pagesUnited NationsKapil Sharma100% (1)

- Peaceful Settlement of Disputes - Dr. Walid Abdulrahim Professor of LawDocument18 pagesPeaceful Settlement of Disputes - Dr. Walid Abdulrahim Professor of LawThejaNo ratings yet

- Theories As To The Basis of Intl LawDocument14 pagesTheories As To The Basis of Intl LawsandeepNo ratings yet

- Assingment Case Study Practical Training III Roll Div 1Document23 pagesAssingment Case Study Practical Training III Roll Div 1Swatantraprakash Yadav100% (1)

- Parker (United States.) v. United Mexican StatesDocument8 pagesParker (United States.) v. United Mexican StatescontestantlauNo ratings yet

- Poli Bar QuestionsDocument34 pagesPoli Bar QuestionsJave Mike AtonNo ratings yet

- Philippine Manual of Legal CitationsDocument115 pagesPhilippine Manual of Legal CitationsEn Zo67% (3)

- 1505 - ApplicantDocument35 pages1505 - ApplicantSanchit Shrivastava25% (4)

- Public International LAWDocument12 pagesPublic International LAWJennylyn Biltz Albano0% (1)

- CW Midterm ModuleDocument22 pagesCW Midterm ModuleAppoch Kaye RolloqueNo ratings yet

- A.K. Jain Public International LawDocument236 pagesA.K. Jain Public International LawRohan Patel100% (2)

- HRs and IHL - Cordula DroegeDocument47 pagesHRs and IHL - Cordula DroegeAyushi AgarwalNo ratings yet

- 3.mills - JurisdiccionDocument53 pages3.mills - JurisdiccionBrigitte RyszelNo ratings yet

- United Nations - WiDocument42 pagesUnited Nations - WiFilopeNo ratings yet

- International Law AssignmentDocument20 pagesInternational Law Assignmentkunal mehtoNo ratings yet

- Sources of Human RightsDocument5 pagesSources of Human RightsSebin JamesNo ratings yet

- Legal Language Project On JurisdictionDocument12 pagesLegal Language Project On JurisdictionAkshat TiwaryNo ratings yet

- International Humanitarian Law and Human RightsDocument609 pagesInternational Humanitarian Law and Human RightsKH Esclares-Prado100% (2)

- For the Thrill of It: Leopold, Loeb, and the Murder That Shocked Jazz Age ChicagoFrom EverandFor the Thrill of It: Leopold, Loeb, and the Murder That Shocked Jazz Age ChicagoRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (97)

- Reasonable Doubts: The O.J. Simpson Case and the Criminal Justice SystemFrom EverandReasonable Doubts: The O.J. Simpson Case and the Criminal Justice SystemRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (25)

- Perversion of Justice: The Jeffrey Epstein StoryFrom EverandPerversion of Justice: The Jeffrey Epstein StoryRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (10)

- Dean Corll: The True Story of The Houston Mass MurdersFrom EverandDean Corll: The True Story of The Houston Mass MurdersRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (29)

- Hunting Whitey: The Inside Story of the Capture & Killing of America's Most Wanted Crime BossFrom EverandHunting Whitey: The Inside Story of the Capture & Killing of America's Most Wanted Crime BossRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (6)

- The Killer Across the Table: Unlocking the Secrets of Serial Killers and Predators with the FBI's Original MindhunterFrom EverandThe Killer Across the Table: Unlocking the Secrets of Serial Killers and Predators with the FBI's Original MindhunterRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (112)

- Lady Killers: Deadly Women Throughout HistoryFrom EverandLady Killers: Deadly Women Throughout HistoryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (155)

- The Edge of Innocence: The Trial of Casper BennettFrom EverandThe Edge of Innocence: The Trial of Casper BennettRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- The Killer Across the Table: Unlocking the Secrets of Serial Killers and Predators with the FBI's Original MindhunterFrom EverandThe Killer Across the Table: Unlocking the Secrets of Serial Killers and Predators with the FBI's Original MindhunterRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (456)

- The Death of Punishment: Searching for Justice among the Worst of the WorstFrom EverandThe Death of Punishment: Searching for Justice among the Worst of the WorstNo ratings yet

- A Warrant to Kill: A True Story of Obsession, Lies and a Killer CopFrom EverandA Warrant to Kill: A True Story of Obsession, Lies and a Killer CopRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (21)

- Ice and Bone: Tracking an Alaskan Serial KillerFrom EverandIce and Bone: Tracking an Alaskan Serial KillerRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (7)

- O.J. Is Innocent and I Can Prove It: The Shocking Truth about the Murders of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron GoldmanFrom EverandO.J. Is Innocent and I Can Prove It: The Shocking Truth about the Murders of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron GoldmanRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Conviction: The Untold Story of Putting Jodi Arias Behind BarsFrom EverandConviction: The Untold Story of Putting Jodi Arias Behind BarsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (16)

- The Secret Barrister: Stories of the Law and How It's BrokenFrom EverandThe Secret Barrister: Stories of the Law and How It's BrokenRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (12)

- Just Mercy: a story of justice and redemptionFrom EverandJust Mercy: a story of justice and redemptionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (175)

- The Only Story That Has Not Been Told About OJ: What if he wasn't guilty?From EverandThe Only Story That Has Not Been Told About OJ: What if he wasn't guilty?No ratings yet

- I Don't Like Mondays: The True Story Behind America's First Modern School ShootingFrom EverandI Don't Like Mondays: The True Story Behind America's First Modern School ShootingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Kidnapped by a Client: The Incredible True Story of an Attorney's Fight for JusticeFrom EverandKidnapped by a Client: The Incredible True Story of an Attorney's Fight for JusticeRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Innocent Blood: A True Story of Obsession and Serial MurderFrom EverandInnocent Blood: A True Story of Obsession and Serial MurderRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (72)

- What's Prison For?: Punishment and Rehabilitation in the Age of Mass IncarcerationFrom EverandWhat's Prison For?: Punishment and Rehabilitation in the Age of Mass IncarcerationNo ratings yet

- Life Sentence: The Brief and Tragic Career of Baltimore’s Deadliest Gang LeaderFrom EverandLife Sentence: The Brief and Tragic Career of Baltimore’s Deadliest Gang LeaderRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (16)

- Wolf Boys: Two American Teenagers and Mexico's Most Dangerous Drug CartelFrom EverandWolf Boys: Two American Teenagers and Mexico's Most Dangerous Drug CartelRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (61)

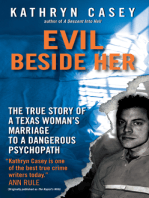

- Evil Beside Her: The True Story of a Texas Woman's Marriage to a Dangerous PsychopathFrom EverandEvil Beside Her: The True Story of a Texas Woman's Marriage to a Dangerous PsychopathRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (47)