Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Global History of The 19th Century (2014) Came Out in English, One Reviewer

Uploaded by

Jearim Yael Andrade San Martín0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

30 views7 pagesklñlo

Original Title

Global History

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentklñlo

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

30 views7 pagesGlobal History of The 19th Century (2014) Came Out in English, One Reviewer

Uploaded by

Jearim Yael Andrade San Martínklñlo

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 7

Essays:

What is global history now?

Jeremy Adelman

Well, that was a short ride. Not long ago, one of the world’s leading historians,

Lynn Hunt, stated with confidence in Writing History in the Global Era (2014) that

a more global approach to the past would do for our age what national history did

in the heyday of nation-building: it would, as Jean-Jacques Rousseau had said was

necessary of the nation-builders, remake people from the inside out. Global history

would produce tolerant and cosmopolitan global citizens. It rendered the past a

mirror on our future border-crossing selves – not unlike Barack Obama, the son of

a Kenyan father and white American mother, raised in Indonesia and educated in

the Ivy League, who became the passing figure of our fading dreams of meritocracy

without walls.

The mild-mannered German historian Jürgen Osterhammel might serve as an

example of that global turn. When his book The Transformation of the World: A

Global History of the 19th Century (2014) came out in English, one reviewer

baptised him the new Fernand Braudel. It was already a sensation in Germany. One

day, Osterhammel’s office phone at the University of Konstanz rang. On the other

end of the line was the country’s chancellor, Angela Merkel. ‘You don’t check your

SMSs,’ she scolded lightly. At the time, Merkel was on the mend from a broken

pelvis and the political fallout of the Eurocrisis. While recovering, she’d read

Osterhammel’s 1,200-page book for therapy. She was calling to invite the author to

her 60th-birthday party to lecture her guests about time and global perspectives.

Obsessed with the rise of China and the consequences of digitalisation, she had

turned to the sage of the moment: the global historian.

It’s hard to imagine Osterhammel getting invited to the party now. In our fevered

present of Nation-X First, of resurgent ethno-nationalism, what’s the point of

recovering global pasts? Merkel, daughter of the East, might be the improbable last

voice of Atlantic Charter internationalism. Two years after her 60th birthday, the

vision of an integrated future and spreading tolerance is beating a hasty retreat.

What is to become of this approach to the past, one that a short time ago promised

to re-image a vintage discipline? What would global narratives look like in the age

of an anti-global backlash? Does the rise of ‘America First’, ‘China First’, ‘India First’

and ‘Russia First’ mean that the dreams and work of globe-narrating historians

were just a bender, a neo-liberal joyride?

Until very recently, the practice of modern history centred on, and was dominated

by, the nation state. Most history was the history of the nation. If you wander

through the history and biography aisles of either brick-and-mortar or virtual

bookstores, the characters and heroes of patriotism dominate. In the United States,

authors such as Walter Isaacson, David McCullough and Doris Kearns Goodwin

have helped to give millions of readers their understanding of the past and the

present. Inevitably, they wrote page-turning profiles of heroic nation-builders.

Every nation cherishes its national history, and every country has a cadre of flame-

keepers.

Then, along came globalisation and the shake-up of old, bordered imaginations.

Historians quickly responded to the fall of the Berlin Wall, the crumbling

protective ramparts of national capitalism, the boom in container shipping, and the

rise of the cosmopolis. New scales and new concepts came to life. Europe’s

Schengen Agreement, inked in 1985, the North American Free Trade Agreement in

1993, and the founding of the World Trade Organization in 1995, heralded new

levels of international fusion. These now-imperilled treaties promised a borderless

world. ‘The world is being flattened,’ Thomas Friedman’s popular manifesto of

globalisation, The World Is Flat (2005), concluded. ‘I didn’t start it and you can’t

stop it,’ Friedman wrote in an open letter to his daughter, ‘except at great cost to

human development and your own future.’

As the only game in town, globalisation produced a new popular genre that might

be called patriotic globalism. Samantha Power’s A Problem from Hell: America and

the Age of Genocide (2002), Philip Gourevitch’s We Wish to Inform You That

Tomorrow We Will Be Killed with Our Families (1998), and books by Adam

Hochschild all gave us horrible crises with would-be heroes fashioned, not as

nation-builders, but as humanitarian worldmakers. There was also a surge of

stories about a shared, planetary future, with a common, carbon-addicted past. The

Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit in 1992 turned sustainability into a border-busting

buzzword and fuelled environmental history. Two decades earlier, Alfred Crosby

could not find a publisher who wanted his book The Columbian Exchange (1972),

which charted the ecological fallout of the integration of the New World biome into

the Eurasian system. Now, his book is Biblical.

After years of falling enrolments, declining majors and a dispiriting job market,

many saw ‘global history’ as an elixir

In 2006, the scholars jumped officially on board. A team founded the Journal of

Global History. Patrick O’Brien at the London School of Economics kicked it off with

a call for new cosmopolitan meta-narratives for ‘our globalising world’. It was

dedicated to stories to transcend (quoting the 18th-century Tory philosopher Lord

Bolingbroke) ‘national partialities and prejudices’. Behind the scenes, universities

in Europe (which includes, for a few more months at least, the United Kingdom),

pockets in Japan, China and Brazil, but most especially in the US, rolled out new

courses, new research centres, and new PhD programmes.

After years of falling enrolments, declining majors and a dispiriting job market for

history PhDs, many saw ‘global history’ as an elixir, a way to return to public

relevance. Globalisation had become all the rage. Historians, Hunt wrote in 2014,

were stepping up with narratives of interconnection and integration. Jared

Diamond’s works, synthesising 13,000 years of global history, populated airport

newsstands. To get middle- and high-school students jazzed up about history on a

cosmological scale – ‘13.8 Billion Years of History. Free. Online. Awesome’ – Bill

Gates unveiled his Big History Project. More recently, Sven Beckert’s Empire of

Cotton: A Global History (2014) swept prizes and hit No 1 on Amazon’s bestseller

ranks under the ‘Fashion and Textile’ category.

To understand what global history was, it helps to understand what it was

supposed to eclipse. It used to be that, in the US, history departments had their

cores in American and/or European fields; in Canada, Australia and Britain, the

nuclei were also national. History meant the history of the nation, its peoples and

their origins. When social and cultural history came along, it changed the subject

from presidents or prime ministers to Hollywood or garment workers. But the

framework remained mostly national; historians still wrote books about the

making of the English working class, or the conversion of peasants into French

citizens. There might be a smattering of East Asian or Latin American historians in

the mix. Often, they were cordoned into regional studies units, or lumped – as in

my home department at Princeton – as ‘non-Western historians’, defined by their

fundamental difference, there to embellish but not challenge the national canon.

The major exception was the study of migrations and diasporas, coerced or free.

But even those fields tended to sit alongside the national behemoths; there was the

American history survey (or French, or British), and then the story of African-

Americans.

True, there has long been something called ‘world history’. The standard world

history course was a tour of the civilisations that preceded or abutted ‘Western

Civilisation’. The Western Civ industry dated to the early years of the 20th century.

Back then, faced with creeping specialisation, historians got summoned to offer a

structured base for the national collegian-citizen. With household names such as

Arnold Toynbee and Will and Ariel Durant it boomed, like the rest of American

industry, in the golden age of NATO, Sputnik and federal spending. One of its

greatest figures was the University of Chicago historian William H McNeill, author

of the stand-by History of Western Civilisation: A Handbook (1949). As Western Civ

became something of a relic in the 1960s, ‘world history’ or ‘world civilisations’

took its place to explain the Triumph of the West and, by extension, the Decline of

the Rest. McNeill’s epic The Rise of the West (1963) was the high-standard bearer

for this kind of encompassing view of the planetary past composed of civilisational

blocs competing for global supremacy. This was not global history, though many

subsequent global historians cut their teeth studying other civilisations. Rather, it

was a story that brought in the Rest to help explain the West.

Connection was in; networks were hot: global history would show the latticework

of exchanges and encounters

By the 1980s, it was no longer foregone that the Rest was synonymous with

decline, or the West with rise. The Rest, to some, became the new threat to define

the purpose of the West. Samuel Huntington’s The Clash of Civilisations and the

Remaking of World Order (1996) offered a counterpoint to the emerging bravura of

one-world heroism. In Huntington’s view, the essentially dark, antagonistic,

competitive perspective of the world-civilisations approach remained the driving

force of history. Don’t kid yourself, he argued: the fall of the Berlin Wall merely

heralded the return of an older, deeper civilisational conflict. That message has

new treads with the White House chief strategist Steve Bannon’s prophecies about

the inevitable collision of the ‘Judeo-Christian West’ with the Jihadist East. ‘There is

a major war brewing, a war that’s already global,’ he told an audience in 2014.

‘Every day that we refuse to look at this as what it is, and the scale of it, and really

the viciousness of it, will be a day where you will rue that we didn’t act.’

The notion of intractable divides, however, seemed increasingly at odds with the

high-def, global-fusing present; it mobilised a new generation of historians to go

beyond stories of our walled-off, essential selves. Their global history project

would reveal connections across societies instead of cohesions within them. The

vintage comparative, civilisational framework gave way to contacts and linkages.

Connection was in; networks were hot. Global history would show the latticework

of exchanges and encounters – from the Silk Road of 1300 to turbo-charged supply

chains of 2000.

More than anyone, Sanjay Subrahmanyam, now at the University of California, Los

Angeles, made the coinage of ‘connected histories’ his own. As determined to

dethrone the myth of Indian civilisation (whose Hindutva ideology is dear to the

tribalism of India’s Right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party) as he is to dispel the idea of

a Great European Trajectory (from Athens to the Enlightenment, a march dear to

European tribalists), the son of urbane Delhi turned encounters and contacts with

many origin points and as many meanings into a global bricolage that antedated

our multicultural makeups. Through travel, discovery, translation and the flow of

books, silver and opium – ‘histories that moved’ as Subrahmanyam called them in

his inaugural lecture at the Collège de France in 2013 – he evoked a world laced

together long before the rise of the West.

Global history’s other signature was its emphasis on dependence between

societies. If globalisation opened the borders between Westerners and Resterners,

global historians were especially interested not just in the contacts, but in the ways

in which countries and regions contoured each other. The rise of the West looked

more and more not just like a response to the Rest, but dependent on it. Even the

industrial revolution and Europe’s great leap forward in the 19th century, the one

thing that seemed to separate Europe from others, came under the global

historian’s macroscope. In The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of

the Modern World Economy (2000), Kenneth Pomeranz demolished the view of

Europeans as the authors of their own miraculous rise. He revealed how much

European enterprise and accumulation shared with China. How Europe’s break

from the common, Eurasian-Malthusian straightjacket began not with the region’s

internal uniqueness, but with access to and conquest of what Adam Smith called

the wastelands of the Americas. In the same vein, global historians demonstrated

how much insurance, banking and shipping startups owed to the African slave

trade. The European miracle was, in short, a global harvest.

Global history did not mean telling the story of everything in the world. What was

global was not the object of study, but the emphasis on connections, scale and,

most of all, integration. Even the nations and civilisations were more the products

and less the producers of global interactions. Some scholars went all-out. ‘If you

are not doing an explicitly transnational, international or global project, you now

have to explain why you are not,’ said the Harvard historian David Armitage in

2012. ‘The hegemony of national historiography,’ he pronounced, ‘is over.’

No sooner did historians catch the globalisation wave with fancy new courses,

magazines, textbooks and attention, than the wave seemed to collapse. The story

changed. A powerful political movement arose against ‘globalism’. White-

supremacists and Vladimir Putin fans from the Traditionalist Worker Party in the

US proclaim as their slogan that ‘Globalism is the poison, nationalism is the

antidote.’ Donald Trump put it only a bit more mildly. ‘Americanism, not globalism,

will be our credo,’ he thundered to cheering Republicans in his convention speech

in July 2016. On the day after the US inaugurated Trump, the French presidential

hopeful Marine Le Pen gave an incendiary speech at a summit in Germany, calling

2017 the year of the great awakening of the nationalist Right. ‘We are living

through the end of one world,’ she proclaimed, ‘and the birth of another.’

Suddenly, global historians seemed out of step with their times. If the backlash was

a wake-up call for the globalisers, it also revealed some problems for the global

chroniclers.

All narratives are selective, shaped as much by what they exclude as what they

include. Despite the mantras of integration and the inclusion on the planetary

scale, global history came with its own segregation – starting with language.

Historians working across borders merged their mode of communication in ways

that created new walls; in the search for academic cohesion, English became

Globish. Global history would not be possible without the globalisation of the

English language. In a recent workshop in Tokyo, I marvelled as Italians, Chinese

and Japanese historians swapped ideas and sake in a lingua franca. But this kind of

flatness can mask a new linguistic hierarchy. It is one of the paradoxes of global

history that the drive to overcome Eurocentrism contributed to the Anglicising of

intellectual lives around the world. As English became Globish, there was less

incentive to learn foreign languages – the indispensable key to bridging ourselves

and others. According to a 2015 report by the Modern Languages Association, the

US foreign-language head count at universities peaked in 2009, and has been

declining ever since.

Global history is another Anglospheric invention to integrate the Other into a

cosmopolitan narrative on our terms, in our tongues

The retreat from learning how to talk with others reflected a wider stall. Despite

the embrace of global history, there is evidence that the global turn didn’t actually

help to raise the profile of the Rest. In a 2013 survey of 57 history departments in

the UK, the US and Canada, Luke Clossey and Nicholas Guyatt show that historians

remain pretty loyal to the West after all. In the UK, 13 per cent of historians study

the non-Western world. The most wincing datum? East Asia commands only 1.9

per cent of all history faculty appointments in the UK. In the US, the figure is almost

9 per cent. Even in the US, less than one-third of historians are interested in the

world beyond the West. If some critics were getting all worked up about the

encroachment of Resterners on the Western Civ canon, they needn’t worry. ‘We’re

overwhelmingly interested in ourselves,’ Clossey and Guyatt conclude. To justify

Brexit, the UK’s prime minister Theresa May yearns for a ‘Global Britain’ (as if

Europe were not part of the globe), but UK historians still look inwards; 41 per

cent of historians in the UK study Britain and Ireland, homelands to 1 per cent of

the world’s population. Oxford University, my alma mater, recently mothballed its

professorship in Latin American history, the last of its kind in the UK. Outside the

Anglosphere, things are mostly worse. In all the German-speaking universities,

there are only five professors of African history. In Japan, to study non-Japanese

and non-‘Oriental’ pasts means dispatch from history departments altogether, to

teach about the Other in other units on the margins of the master-discipline.

What are we to make of all this? First, the high hopes for cosmopolitan narratives

about ‘encounters’ between Westerners and Resterners led to some pretty one-

way exchanges about the shape of the global. It is hard not to conclude that global

history is another Anglospheric invention to integrate the Other into a

cosmopolitan narrative on our terms, in our tongues. Sort of like the wider world

economy.

Secondly, to some extent, global history sounds like history fit for the now-defunct

Clinton Global Initiative, a shiny, high-profile endeavour emphasising borderless,

do-good storytelling about our cosmopolitan commonness, global history to give

globalisation a human face. It privileged motion over place, histoires qui

bougent (stories that move) over tales of those who got left behind, narratives

about others for the selves who felt some connection – of shared self-interest or

empathy – between far-flung neighbours of the global cosmopolis.

Perhaps we should not be shocked at the backlash against post-national,

cosmopolitan story-telling. During the French regional elections of 2015, one Front

National poster featured two women’s faces, one painted with the French tricolour

and the other wearing a burqa. The text proclaimed: ‘Choose your neighborhood:

vote for the Front.’ The logic of global history tended to dwell on integration and

concord, rather than disintegration and discord. Global historians favoured stories

about curiosity towards distant neighbours. They – we – tended to overlook

nearby neighbourhoods dissolved by transnational supply chains.

Global history preferred a scale that reflected its cosmopolitan self-yearnings. It

also implicitly created what the sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild in Strangers in

Their Own Land (2016) called ‘empathy walls’ between globe-trotting liberals and

locally rooted provincials. Going global often meant losing contact with – to

borrow another of her bons mots – ‘deep stories’ of resentment about loss of and

threat to local attachments. The older patriotic narratives had tethered people to a

sense of bounded unity. The new, cosmopolitan, global narratives crossed those

boundaries. But they dissolved the heartlanders’ ties to a sense of place in the

world. In a political climate dominated by railing against Leviathan government,

big banks, mega-treaties with inscrutable acronyms such as TPP, and distant

Eurocrats, the pretentious drive to replace deep stories of near-mourning with

global stories of distant connection was bound to face its limits. In the scramble to

make Others part of our stories, we inadvertently created a new swath of strangers

at home.

Global history faces two seemingly opposite challenges for an inter-dependent,

over-heating planet. If we are going to muster meaningful narratives about the

togetherness of strangers near and far, we are going to have to be more global and

get more serious about engaging other languages and other ways of telling history.

Historians and their reader-citizens are also going to have to re-signify the place of

local attachments and meanings. Going deeper into the stories of Others afar and

Strangers at home means dispensing with the idea that global integration was like

an electric circuit, bringing light to the connected. Becoming inter-dependent is not

just messier than drawing a wiring diagram. It means reckoning with dimensions

of networks and circuits that global historians – and possibly all narratives of

cosmopolitan convergence – leave out of the story: lighting up corners of the earth

leaves others in the dark. The story of the globalists illuminates some at the

expense of others, the left behind, the ones who cannot move, and those who

become immobilised because the light no longer shines on them.

To shift the imagery: understanding inter-dependence means seeing how it

expands personal and social horizons for some, but also thins bonds with

others. At least until those bonds become more meaningful than an Instagram list,

there will be much more resistance to integration than we have admitted.

To gain better insights into the dynamics and resistances to integration, to give as

much airtime to separation, disintegration and fragility as we do to connection,

integration and convergence, we are going to have to get rid of flat-Earth

narratives and ideas of global predestination once and for all. We are going to have

to account for how more interdependence can yield more conflict, how for

instance, despite growing trade and student exchanges between China and Japan,

Beijing can announce (as it did in 2014) two new national holidays to

commemorate the victims of Japanese aggression from 1937 to 1945.

Connection, mobility, fusion, oneness: we put our stock in the magnetism of the

market and the empathetic power of a cosmopolitan spirit that appeared to take

hold of the upper echelons of a higher education committed to an idyll of global

citizenship.

I did my own part in the global pivot. For several years, I oversaw Princeton’s

internationalisation drive, creating global knowledge supply chains. It never

occurred to me, or to others, to ask: what would happen to those less sexy,

diminutive, scales of civic engagement? We didn’t worry much. They were the

remits of provincialism, quietly escorted from the stage upon which we were

supposed to be educating the new homo globus.

During globalisation’s up-cycle, it was easier to overlook the divides. When

economies slumped, and globalisation fatigue set in, the gauzy veil came off.

This does not make global history less pressing. On the contrary. One of the ironies

is that the anti-globalism movement is immersed in transnational mutual

adoration networks. The day after the Brexit plebiscite, Trump travelled to the UK

to reopen his golf resort. The British had ‘taken back their country’, he told the

bristle of microphones, then returned home to Make America Great Again. Le Pen’s

excitement about Trump is well-known. Fyodor V Biryukov, head of Rodina, the

Russian Motherland Party, calls this swarm ‘a new global revolution’. It was, we

should recall, the global financial crisis of 2008-9 that did the most to ravage the

hopes of one-world dreamers, emanating from the sector that had gone furthest to

fuse Westerners and Resterners while creating deeper divides at home: banking.

In short, we need narratives of global life that reckon with disintegration as well as

integration, the costs and not just the bounty of interdependence. They might not

do well on the chirpy TED-talk circuit, compete with Friedman’s unbridled faith in

borderless technocracy, or appeal much to Davos Man. But if we are going to come

to terms with the deep histories of global transformations, we need to remind

ourselves of one of the historian’s crafts, and listen to the other half of the globe,

the tribalists out there and right here, talking back.

You might also like

- ALLATSON - Ilan Stavans's Latino USA - A Cartoon HistoryDocument22 pagesALLATSON - Ilan Stavans's Latino USA - A Cartoon HistoryNerakNo ratings yet

- Fidel Castro: My Life: A Spoken AutobiographyFrom EverandFidel Castro: My Life: A Spoken AutobiographyRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (14)

- Conspiracy: How the Paranoid Style Flourishes and Where It Comes FromFrom EverandConspiracy: How the Paranoid Style Flourishes and Where It Comes FromRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- On Western Terrorism: From Hiroshima to Drone WarfareFrom EverandOn Western Terrorism: From Hiroshima to Drone WarfareRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (16)

- Jeremy Adelman - What Is Global History NowDocument16 pagesJeremy Adelman - What Is Global History NowAlex Aravena RubioNo ratings yet

- International Business 8th Edition Czinkota Test BankDocument27 pagesInternational Business 8th Edition Czinkota Test Bankstephenhooverfjkaztqgrs100% (11)

- Case Discussion Questions: Criteria China Plant San Francisco PlantDocument2 pagesCase Discussion Questions: Criteria China Plant San Francisco PlantPragya Singh BaghelNo ratings yet

- Close Encounters of EmpiresDocument593 pagesClose Encounters of Empiresanapaula1978No ratings yet

- Pest Analysis of Pharma IndustryDocument10 pagesPest Analysis of Pharma IndustryNirmal75% (4)

- A GuideDocument23 pagesA GuideMuhajir AlarabiNo ratings yet

- With Dignity, Hope, and Joy: The Latin American Youth Center: A Case StudyDocument100 pagesWith Dignity, Hope, and Joy: The Latin American Youth Center: A Case Studyscholar1968No ratings yet

- What Is Global History Now ALDEMAN JeremyDocument9 pagesWhat Is Global History Now ALDEMAN JeremyIsabela CarneiroNo ratings yet

- Voyage of the Damned: A Shocking True Story of Hope, Betrayal, and Nazi TerrorFrom EverandVoyage of the Damned: A Shocking True Story of Hope, Betrayal, and Nazi TerrorRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (25)

- Not Stolen: The Truth About European Colonialism in the New WorldFrom EverandNot Stolen: The Truth About European Colonialism in the New WorldRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- The Return of History: Conflict, Migration, and Geopolitics in the Twenty-First CenturyFrom EverandThe Return of History: Conflict, Migration, and Geopolitics in the Twenty-First CenturyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (12)

- HHB ch3Document45 pagesHHB ch3susanwhittenNo ratings yet

- Book Reviews 119: University of California, IrvineDocument4 pagesBook Reviews 119: University of California, IrvineGuido DiblasiNo ratings yet

- The American Short Story. A Chronological History: Volume 5 - Robert W Chambers to Ellen GlasgowFrom EverandThe American Short Story. A Chronological History: Volume 5 - Robert W Chambers to Ellen GlasgowNo ratings yet

- Dublin Easter 1916 The French Connection: The French ConnectionFrom EverandDublin Easter 1916 The French Connection: The French ConnectionNo ratings yet

- The Politics of Genocide - Edward S. HermanDocument245 pagesThe Politics of Genocide - Edward S. Hermanuppaimappla100% (1)

- Modern Times Paul Johnson ThesisDocument6 pagesModern Times Paul Johnson Thesisjennawelchhartford100% (2)

- James Clifford - Après CoupDocument7 pagesJames Clifford - Après CoupSonyNo ratings yet

- The Lost Generation-StudentDocument11 pagesThe Lost Generation-StudentjheatonNo ratings yet

- Mapping the Millennium: Behind the Plans of the New World OrderFrom EverandMapping the Millennium: Behind the Plans of the New World OrderRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- The Decline of The West: An American StoryDocument21 pagesThe Decline of The West: An American StoryGerman Marshall Fund of the United States100% (1)

- The United States and The State of IsraelDocument419 pagesThe United States and The State of Israelcofitabs100% (1)

- Literature Review NationalismDocument8 pagesLiterature Review Nationalismc5qvh6b4100% (1)

- Title Description Publisher AuthorDocument8 pagesTitle Description Publisher Authorankitch123No ratings yet

- The Significance of The Frontier in American IdeologyDocument13 pagesThe Significance of The Frontier in American Ideologyaerpel100% (1)

- Washington and the Hope of Peace; Or, Washington and the Riddle of PeaceFrom EverandWashington and the Hope of Peace; Or, Washington and the Riddle of PeaceNo ratings yet

- The Dead Do Not Die: "Exterminate All the Brutes" and Terra NulliusFrom EverandThe Dead Do Not Die: "Exterminate All the Brutes" and Terra NulliusRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- Cultural Revolutions: Reason Versus Culture in Philosophy, Politics, and JihadFrom EverandCultural Revolutions: Reason Versus Culture in Philosophy, Politics, and JihadNo ratings yet

- Schiller InstituteTHE NEW DARK AGE The Frankfurt School and Political CorrectnessDocument21 pagesSchiller InstituteTHE NEW DARK AGE The Frankfurt School and Political Correctness300rNo ratings yet

- Deadly Contradictions: The New American Empire and Global WarringFrom EverandDeadly Contradictions: The New American Empire and Global WarringNo ratings yet

- The Untold History of the United States, Volume 2: Young Readers Edition, 1945-1962From EverandThe Untold History of the United States, Volume 2: Young Readers Edition, 1945-1962Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Lost Promise of Patriotism: Debating American Identity, 1890-1920From EverandThe Lost Promise of Patriotism: Debating American Identity, 1890-1920No ratings yet

- America's Hidden History: Untold Tales of the First Pilgrims, Fighting Women, and Forgotten Founders Who Shaped a NationFrom EverandAmerica's Hidden History: Untold Tales of the First Pilgrims, Fighting Women, and Forgotten Founders Who Shaped a NationRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (121)

- 1920s Culture CarouselDocument7 pages1920s Culture CarouselEllen BrueggerNo ratings yet

- Holt Modernism HistoryDocument14 pagesHolt Modernism HistoryAna HuembesNo ratings yet

- Revenge of The Neanderthal by Willis CartoDocument23 pagesRevenge of The Neanderthal by Willis CartoPeter FredricksNo ratings yet

- Not Forgotten: Elegies for, and Reminiscences of, a Diverse Cast of Characters, Most of Them AdmirableFrom EverandNot Forgotten: Elegies for, and Reminiscences of, a Diverse Cast of Characters, Most of Them AdmirableNo ratings yet

- The Grand DesignDocument27 pagesThe Grand DesignHans FandinoNo ratings yet

- Conflicts of Interest: Canada and the Third WorldFrom EverandConflicts of Interest: Canada and the Third WorldRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Facing Racial Revolution: Eyewitness Accounts of the Haitian InsurrectionFrom EverandFacing Racial Revolution: Eyewitness Accounts of the Haitian InsurrectionNo ratings yet

- Migration and State Power: Global Humanities. Studies in Histories, Cultures and Societies 03/2016From EverandMigration and State Power: Global Humanities. Studies in Histories, Cultures and Societies 03/2016No ratings yet

- #Hashtags# #Congresomua2018 #Congresomua #Congresonacionalmua #Muaamch #Muauchile #Universitariosadventistas #Iasd #Pcm2018 #UchileDocument1 page#Hashtags# #Congresomua2018 #Congresomua #Congresonacionalmua #Muaamch #Muauchile #Universitariosadventistas #Iasd #Pcm2018 #UchileJearim Yael Andrade San MartínNo ratings yet

- Taylor Swift - Untouchable (Uke Cifras)Document2 pagesTaylor Swift - Untouchable (Uke Cifras)Jearim Yael Andrade San MartínNo ratings yet

- Taylor Swift - CrazierDocument2 pagesTaylor Swift - CrazierJearim Yael Andrade San MartínNo ratings yet

- Taylor Swift - Last Kiss (Uke Cifras)Document1 pageTaylor Swift - Last Kiss (Uke Cifras)Jearim Yael Andrade San MartínNo ratings yet

- Lea Michele - Heavy Love (Uke Cifras) PDFDocument1 pageLea Michele - Heavy Love (Uke Cifras) PDFJearim Yael Andrade San MartínNo ratings yet

- Lea Michele - Love Is Alive (Uke Cifras)Document1 pageLea Michele - Love Is Alive (Uke Cifras)Jearim Yael Andrade San MartínNo ratings yet

- Lea Michele - Believer (Uke Cifras) PDFDocument1 pageLea Michele - Believer (Uke Cifras) PDFJearim Yael Andrade San MartínNo ratings yet

- Lea Michele - Heavy Love (Uke Cifras)Document1 pageLea Michele - Heavy Love (Uke Cifras)Jearim Yael Andrade San MartínNo ratings yet

- Lea Michele - Believer (Uke Cifras) PDFDocument1 pageLea Michele - Believer (Uke Cifras) PDFJearim Yael Andrade San MartínNo ratings yet

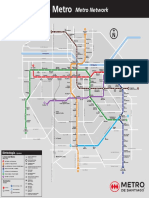

- Metrored Servicios 2018 PDFDocument1 pageMetrored Servicios 2018 PDFJearim Yael Andrade San MartínNo ratings yet

- NASSCOM McKinsey Report 2005Document11 pagesNASSCOM McKinsey Report 2005hrassiwallaNo ratings yet

- 5926 Supplemental Statement 20150130 12Document45 pages5926 Supplemental Statement 20150130 12Mihai IvaşcuNo ratings yet

- Seattle Planning Commission 2020 Growth Strategy White PaperDocument18 pagesSeattle Planning Commission 2020 Growth Strategy White PaperThe Urbanist100% (1)

- Martin Luther King Jr. (Born Michael King Jr. January 15, 1929 - April 4, 1968) Was An AmericanDocument1 pageMartin Luther King Jr. (Born Michael King Jr. January 15, 1929 - April 4, 1968) Was An AmericanJordan DonovanNo ratings yet

- Friedman and Ekholm Ameth 2013 FinDocument14 pagesFriedman and Ekholm Ameth 2013 FinJonathan FriedmanNo ratings yet

- Group Discussion TopicsDocument19 pagesGroup Discussion TopicsVeeraragavan SubramaniamNo ratings yet

- Rule: Federal Management Regulation (FMR) : Surplus Personal Property DonationDocument2 pagesRule: Federal Management Regulation (FMR) : Surplus Personal Property DonationJustia.comNo ratings yet

- Most Expected Css QuestionsDocument7 pagesMost Expected Css QuestionsMůṥāwwir Abbāś AttāriNo ratings yet

- Reading Questions - Chapter 27 ApushDocument4 pagesReading Questions - Chapter 27 ApushLaurel HouleNo ratings yet

- 02-06-18 EditionDocument28 pages02-06-18 EditionSan Mateo Daily JournalNo ratings yet

- Silent MassacreDocument222 pagesSilent MassacreChris Lissa MyersNo ratings yet

- Critical Mission: Essays On Democracy PromotionDocument283 pagesCritical Mission: Essays On Democracy PromotionCarnegie Endowment for International Peace100% (1)

- Mignolo Interview PluriversityDocument38 pagesMignolo Interview PluriversityJamille Pinheiro DiasNo ratings yet

- Morel - Black Mans BurdenDocument268 pagesMorel - Black Mans BurdennkiakoNo ratings yet

- American OpportunityDocument52 pagesAmerican OpportunityAlejandro Juárez ZepedaNo ratings yet

- Notice: Program Exclusions ListDocument6 pagesNotice: Program Exclusions ListJustia.comNo ratings yet

- Gordon Eden ResumeDocument13 pagesGordon Eden ResumeKOB4No ratings yet

- Book Review of Dragon FireDocument4 pagesBook Review of Dragon Fireif u can't, who canNo ratings yet

- Texas Government Term Paper TopicsDocument8 pagesTexas Government Term Paper Topicsc5eyjfntNo ratings yet

- Ditch Witch Locations 2 0Document30 pagesDitch Witch Locations 2 0api-325800611No ratings yet

- Claudia Strauss PDFDocument3 pagesClaudia Strauss PDFsorokzNo ratings yet

- Letter From Mr. Paul DesfossesDocument2 pagesLetter From Mr. Paul DesfossesPhilHart0% (1)

- 06 GOLAY - Face of Empire - Chapter 4-7 PDFDocument72 pages06 GOLAY - Face of Empire - Chapter 4-7 PDFMark Kenneth BaldoqueNo ratings yet