Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Khang MoeSuccessCriteriaandFactorsforInternationalDevelopmentProjects ALifeCycle BasedFrameworkProjectManagementJ.v.3912008

Uploaded by

piamus2Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Khang MoeSuccessCriteriaandFactorsforInternationalDevelopmentProjects ALifeCycle BasedFrameworkProjectManagementJ.v.3912008

Uploaded by

piamus2Copyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/227714640

Success Criteria and Factors for International Development Projects: A Life-

Cycle-Based Framework

Article in Project Management Journal · March 2008

DOI: 10.1002/pmj.20034

CITATIONS READS

176 2,404

2 authors:

Khang Do Ba Dean Kyne

Asian Institute of Technology University of Texas Rio Grande Valley

41 PUBLICATIONS 1,046 CITATIONS 24 PUBLICATIONS 513 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Decision Making View project

PhD research View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Dean Kyne on 03 January 2018.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

PAPERS Success Criteria and Factors for

International Development Projects:

A Life-Cycle-Based Framework

Do Ba Khang, Asian Institute of Technology, Thailand

Tun Lin Moe, Pennsylvania State University, Harrisburg, PA, USA

ABSTRACT ■ INTRODUCTION ■

ot-for-profit development projects, especially those financed with

The paper presents a new conceptual model for

not-for-profit international development proj-

ects that identifies different sets of success cri-

teria and factors in the project life-cycle phases

and then provides the dynamic linkages among

these criteria and factors. The model can serve

N international development aid, play a vital role in the socioeco-

nomic development process of developing countries. According to

the United Nations Development Programme’s (UNDP’s) Human

Development Report (2004), the 49 least developed countries in the world

received US $55.15 billion in Official Development Assistance (ODA) in 2004;

that is 8.9% of their total GDP.

as a basis to evaluate the project status and to

The success of these projects determines the socioeconomic progress in

forecast the results progressively throughout

the recipient countries but also the effectiveness of the contribution of the

the stages. Thus, it helps the project manage-

donor countries and agencies. Understanding the critical factors that influ-

ment team and the key stakeholders prioritize

ence project success enhances the ability of donors and implementing agen-

their attention and scarce development resour-

cies to ensure desired outcomes. In addition, it helps them forecast the future

ces to ensure successful project completion.

status of the project, diagnose the problem areas, and prioritize their atten-

Empirical data from a field survey conducted in

tion and scarce resources to ensure successful completion of the projects.

selected Southeast Asian countries confirm the

Critical success factors for business or profit-oriented projects such as

model’s validity and also illustrate important

construction projects, information technology projects, defense projects,

managerial implications.

and so on have received significant research interest in the last two decades

based on the pioneering research by Pinto and Slevin (1987, 1989). However,

KEYWORDS: project success criteria; criti-

little of this research pays adequate attention to international development

cal success factors; international develop-

projects that possess significant differentiating characteristics, especially the

ment projects; project life cycle

social and not-for-profit nature of the projects, the complex relationships of

the stakeholders involved, and the intangibility of the developmental results.

At the same time, the factors identified in the literature reviewed were mostly

focused on either success of the project implementation or the overall success

of the project and failed to explicitly list the factors relevant for the different

life-cycle phases of the project. As a result, they cannot be used to progressively

measure the project performance early in the project life to timely diagnose

project problems.

The paper aims to contribute to the general project management body of

knowledge by addressing the international development projects that take

place in the developing countries. The majority of funding for these projects

is from the Official Development Assistance provided by the OEDC member

countries through multilateral or bilateral aid agencies and usually takes the

form of concessionaire loans, grants, or technical assistance implemented

through the governments of the recipient countries. Other sources of funding

Project Management Journal, Vol. 39, No. 1, 72–84 come from private philanthropic and nongovernment organizations (NGOs).

© 2008 by the Project Management Institute In this study, the authors take a new life-cycle-based approach in developing

Published online in Wiley InterScience a conceptual model to assess and forecast project success that takes into

(www.interscience.wiley.com) account both the frameworks developed earlier for general projects and

DOI: 10.1002/pmj.20034 the specific characteristics and context of the international development

72 March 2008 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj

projects. For this purpose, first the proj- Following this line of research, the goods and services produced to the

ect management literature on success Andersen and Jessen (2000) emphasized project documents, achievement of proj-

factors and criteria is reviewed and the need for separating the task- and ect objectives, completion of the project

then the key characteristics that differ- people-oriented aspects in evaluat- in time and within budget, receiving

entiate the international development ing the project results. They further a high national profile, and receiving a

projects from others are described. An divided the results into 10 elements good reputation among the principal

analysis of these characteristics leads to to give a more comprehensive picture donors.

a dynamic model that identifies differ- of the outcomes of a project. These Compared with the studies on proj-

ent success criteria and factors for the dimensions include the traditional ect success criteria, a considerably

different phases of the project life cycle, time, budget, and quality elements but larger body of knowledge has been

and then links the success criteria of also the usefulness of the products to accumulated on the generic and critical

each phase with that of the subsequent the base organization, the appeal of the factors responsible for the project suc-

phase. results to all stakeholders, the learning cess or failure. Good reviews of the

The framework is tested empirically experience, the motivation for future research conducted over the last four

with a survey conducted with both work, knowledge acquisition, the way decades can be found in Pinto and

ODA and international NGO projects in the final report is prepared and accepted, Slevin (1987), Belassi and Tukel (1996),

selected countries in Southeast Asia. and how the project is closed (Andersen Westerveld (2003), Diallo and Thuillier

Analysis of the data collected confirms & Jessen, 2000). (2004, 2005), and Fortune and White

the validity of the framework and also Other authors (Baccarini, 1999; (2006). From the perspectives relevant

contributes new insights into managing Cooke-Davies, 2002) have adopted the to managing international development

these projects. The proposed frame- Logical Framework Methodology and projects, the most prominent studies of

work provides the project stakeholders observed the need to differentiate two the period suggest that these factors are

with a forecasting and diagnostic tool to different concepts of success for a closely interrelated, and at times over-

evaluate progressively and objectively project: lapping, and can be grouped in three

the project chance of success, and • Project management success is con- major categories: competency, motiva-

therefore to assist in improving the cerned with the traditional time, cost, tion, and the enabling environment.

overall performance. and quality aspects at the comple- The competencies required for

tion of the project. The concept is the project success can be related to the

Project Success Criteria and process oriented and involves the sat- project manager and the team mem-

Factors: A Literature Review isfaction of the users and key stake- bers, or the institutional competencies

Defining criteria to measure project holders at the project completion. of the project team itself. The critical

success has been recognized as a diffi- • Project success is measured against individual competencies—technical,

cult and controversial task (Baccarini, the achievement of the project owner’s interpersonal, and administrative—

1999; Liu & Walker, 1998). Pinto and strategic organizational objectives have been explicitly identified by most

Mantel (1990) attempted to define the and goals, as well as the satisfaction of the authors reviewed. For example,

project success according to three dif- of the users and key stakeholders’ Martin (1974), Locke (1984), and Pinto

ferent dimensions: needs where they relate to the pro- and Slevin (1987) emphasized the need

• The efficiency of the implementation ject’s final product (Baccarini, 1999). for carefully recruiting the right manag-

process that is “an internally oriented er and personnel to ensure project suc-

measure of the performance of the Diallo and Thuillier (2004) was the cess, while Cleland and King (1983)

project team, including such criteria first important empirical research that is highlighted the role of effective training

as staying on schedule, on budget, focused on the specific success criteria to build the capacities required. White

meeting the technical goals of the and factors of international develop- and Fortune (2002) added the relevant

project, and maintaining smooth ment projects. These authors assessed project experiences to these competen-

working relationship within the team the project success as perceived by cies. The institutional competencies

and parent organization.” seven groups of stakeholders: coordi- are commonly recognized as effective

• The perceived quality of the project, nators, task managers, supervisors, control and communication systems,

which includes the project team’s project team, steering committee, ben- good planning and scheduling, abs-

perception of the value and useful- eficiaries, and population at large. They ence of bureaucracy, strong teamwork

ness of the project deliverables. also outlined a comprehensive set of and leadership, lack of dysfunctional

• The client’s satisfaction or an external evaluation criteria that includes satis- conflicts, etc. (Pinto & Slevin, 1989;

performance measure of the project faction of beneficiaries with goods and White & Fortune, 2002; Westerveld,

performance and its team. services generated, conformation of 2003).

March 2008 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj 73

PAPERS

Success Criteria and Factors for International Development Projects

Without the willingness to perform such as political, economical and social and measurable, compared with infra-

and dedication to the project success situations, technical conditions and structure and industrial projects com-

by the manager and the team mem- competitors. Other external factors monly found in the private sector. Even

bers, competencies are useless. Moti- included adequate resources, facility, for projects involving development of

vation factors recognized in the litera- finance and information (Baker, physical infrastructure and facilities,

ture include clear understanding of the Murphy, & Fisher, 1983; Pinto & Slevin, the ultimate “soft” goals of serving sus-

project goals, objectives, and mission 1987; Sayles & Chandler, 1971; White & tainable social and economic develop-

(Anderson & Jessen, 2000; Belassi & Fortune, 2002; Westerveld, 2003). ment always have a priority in the proj-

Tukel, 1996; Martin, 1974; White As pointed out by Pinto and Slevin ect evaluation by key stakeholders. The

& Fortune, 2002). This understanding (1987), the critical success factors vary intangibility of project objectives and

should be supplemented by the com- according to different types of projects. deliverables raises a special challenge

mitments to the project success by all Thus, the results obtained for industrial in managing and evaluating develop-

the project team. Cooke-Davies (2002) and business projects, or even for gen- ment projects that require adaptation

emphasizes the clear assignment of eral projects, may not always be appli- of the existing project management

responsibilities as a way of accomplish- cable to not-for-profit projects that can body of knowledge and adopting new

ing this commitment. Andersen and be very different from those found in tools and concepts to define, monitor

Jessen (2000) refer to clear terms of ref- industry or the private sector. However, and measure the extent that the devel-

erences for the project. Many studies except for the seminal studies of Diallo opment projects achieve these objec-

(for example, Sayles & Chandler, 1971, and Thuillier (2004, 2005), none of the tives. Neglecting this important aspect

White & Fortune, 2002) recommend an researches on project critical success of development projects usually leads

effective monitoring and control factors addressed this important group to the tendency of measuring only

system to reinforce the motivation of of projects. (See Fortune and White resource mobilization and efforts,

the project team. These factors, and the [2006].) The current research follows up rather than results. The consequence is

compatibility of the interests of the the studies by Diallo and Thuillier the inefficient use of development

individuals with those of the project, (2004, 2005) of international develop- funds and long-term lack of accounta-

are even more important for interna- ment projects by taking into considera- bility. As project interventions cannot

tional development projects, where the tion specific critical success factors and be continued forever, most projects

relationships of the project team and criteria for each of the life-cycle phases also have an ultimate goal to produce

the other stakeholders are much more of these projects. positive and significant changes that

complex (Kwak, 2002; Youker, 1999). will be sustained after the external

Communication and trust factors are Characteristics of International assistance comes to an end. This sus-

found empirically by Diallo and Development Projects tainability requirement adds a new

Thuillier (2005) as critical to the success Development projects form a special level to the intangibility of the develop-

of international development projects type of projects that provide socio- ment outcomes.

in sub-Saharan Africa. economic assistance to the developing Another characteristic of most inter-

A project environment mostly countries, or to some specially desig- national development projects is the

refers to the relationship to external nated group of target beneficiaries. complex web of the many stakeholders

conditions and stakeholders, such as These projects differ from industrial or involved (Youker, 1999). Industrial and

funding agencies, implementing agen- commercial projects in several impor- commercial projects usually have two

cies, agencies of recipient governments tant ways, the understanding of which key stakeholders—the client, who pays

and target beneficiaries. An enabling has strong impacts on how the projects for the project, and as a result, gets

environment provides adequate sup- can be managed and evaluated. the benefits from its deliverables,

port from key stakeholders, adequate The objectives of development and the contractor, or implementing

resources, and creates favorable condi- projects, by definition, concern poverty unit, who gets paid for managing the

tions with support from management alleviation and living standards improve- project to achieve the desired results.

and compatible rules and regulations. ment, environment protection, basic International development projects, in

Early research identified top manage- human rights protection, assistance for contrast, commonly involve three sep-

ment support and adequate allocation victims of natural or people-caused arate key stakeholders, namely the

of resources as key environmental fac- disasters, capacity building and devel- funding agency who pays for but does

tors (Cleland & King, 1983; Martin, opment of basic physical and social not use directly the project outputs, the

1974; Pinto & Slevin, 1987). Belassi and infrastructures. These humanitarian and implementing unit, and the target ben-

Tukel (1996) described explicitly the social objectives are usually much less eficiaries who actually benefit from the

factors related to external environment, tangible, with deliverables less visible project outputs but most commonly do

74 March 2008 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj

not pay for the projects. The role sepa- the project document, creating a spe- a development project into a hierarchy

ration of these three key stakeholders cial dilemma for the implementation. of five components: inputs, activities,

has several important implications. The challenges faced by interna- and three levels of the project results—

First, financial accountability by the tional development projects convince outputs (or deliverables), objectives

project management team is often us of the need to refine the existing (or purposes, or outcomes) and goals (or

considered as important as its responsi- evaluation frameworks used in indus- impacts). Following Baccarini’s ap-

bility to complete the projects within try to allow the managers and stake- proach (1999), the success of a project

the time, cost and quality. This is even holders of these projects to assess the is defined at two levels: the project ma-

more important since these projects project performance in a more objec- nagement success, and the project

are implemented in developing coun- tive and consistent manner. This may success.

tries where cases of high-level corrup- be achieved by considering project life Project management success, being

tion often take place. Second, because cycle, and then evaluating the success process oriented, should be assessed by

of the common developmental, cultur- of each phase based on the outputs the input, activity and output elements

al and knowledge gap between donors produced by the activities of the of the LFA, and can be progressively

and the target recipients, the likely mis- phase. These partial successes can evaluated in the different stages of the

match between the real needs and then be integrated into an assessment project. It can be broken down into suc-

capacity of the target groups and the of the overall success of the whole cess of project life-cycle phases, and

understanding and development poli- project. then measured by evaluating the quality

cies of the funding agencies may result The life cycle of most projects can of the end products generated and the

in poor project design, a precursor of be broken into sequential phases that achievement of the results intended for

failure in the implementation. Third, are generally differentiated by the tech- each of these phases. For example, the

complicating the requirements for nical work being carried out, the key conceptualizing phase of an interna-

financial accountability are the efforts actors involved, the deliverables to be tional development project should gen-

by the funding agencies and the gov- generated and the ways these are con- erally be considered as successful if in

ernments of the recipient countries to trolled and approved (Project Manage- this early stage the following conditions

establish rules and procedures to regu- ment Institute [PMI], 2004). Although exist:

late the disbursement and utilization of the number and names of the life-cycle • Correct target beneficiaries have been

the development funds. Set with simi- phases and the precise boundary identified and their relevant needs

lar intention, but by different institu- points may vary largely from one proj- have been assessed to match the

tions with different organizational ect to another, international develop- development priorities of the donors;

cultures and traditions, these various ment projects go through a typical life • An appropriate implementing agency

rules and procedures often contradict cycle including four relatively distinct has been identified and notified that

each other, raising special and unnec- stages. Table 1 summarizes the most is capable and willing to carry out the

essary difficulties during project imple- common scope of the work to be car- proposed project;

mentation. ried out, the end products to be deliv- • Initial awareness and support of all

The lack of market pressures in ered and the parties involved in these key parties concerned have been ade-

appraising and implementing develop- four life-cycle phases. quately raised in order to ensure the

ment projects, combined with the project proposal enters the next plan-

intangibility of their objectives, often The Proposed Life-Cycle-Based ning phase.

makes these projects the target of polit- Framework

ical manipulations. Individual politi- Measuring the success of international The success of the last phase, based

cians and political parties may push for development projects commonly on the smooth closing of the project

infeasible projects, or may oppose involves a high degree of subjective office and all due transactions, and

good projects for their own political judgments, due to the intangibility of acceptance of the end deliverables and

gains. In extreme cases, some donor their objectives. In this research, more the project final reports by the key

countries may use development fund- objective success criteria are developed stakeholders, is the culmination of the

ing to nurture a political alliance with by adopting the Logical Framework success of all the previous phases and

the leaders of the recipient countries, Approach (LFA), a general methodolo- constitutes the overall project manage-

or simply to buy a good conscience gy commonly used by the development ment success.

(Pallage & Robe, 1998). As a conse- community to design, plan, manage Project success, on the other hand,

quence, the real interests of different and communicate their projects reflects the effective use of the project’s

stakeholders in these projects may be (Coleman, 1987; Gasper, 2000; Wiggins final products and the sustainable

different from the stated objectives in & Shields, 1995). The LFA deconstructs achievement of the project purpose

March 2008 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj 75

PAPERS

76

Life-Cycle Phases Key Activities Key Players End Products

Conceptualizing • Identify the potential target beneficiaries and assess • Funding agencies (or their representative) • Needs assessment report

their development needs. • Consultants • Project proposal or

• Align the development priorities of donors, the capacities concept paper

• Implementing agencies

of potential implementing agencies, and the development

needs. • Representatives of target beneficiaries and

local governments

• Develop and evaluate project alternatives.

• Generate interest and support of key stakeholders.

Planning • Develop the project scope and LOGFRAME. • Funding agency (representative) • Project documents including

• Estimate resources required. • Government (representative) • Project scope and LOGFRAME

• Budget

• Mobilize support and commitment. • Consultants • Organizational setup

• Plan for project schedule and organization setup. • Implementing agencies • Schedule

• Negotiate for final approval. • Risk management plan

• Project agreement with resource

and support commitment

March 2008 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj

Implementing • Set up project management team. • Project management team • Resources mobilized

• Review and revise project plan and kick off the project. • Subcontractors, suppliers, partners • Activities carried out

• Carry out the project activities as planned. • Target beneficiaries • Outputs produced and delivered

• Control the project budget and expenses. • Inception report and M&E reports

• Monitor, evaluate, and report project progress and per-

formance.

• Manage relationships with stakeholders.

Closing/ • Final test the project outputs. • Project management team • Project completion report

completing

• Complete the project final report. • Funding agency (representative) • Final settlement of all pending

• Settle all financial transactions with subcontractors, sup- • Government (representative) financial dues

pliers, consultants, etc. • Implementing agencies • Project outputs and assets trans-

Success Criteria and Factors for International Development Projects

• Hand over the project output and asset. ferred

• Bring into public notice the project results and lessons. • Dissolution or transformation of

the project team into an ongoing

• Dissolve or transform the project team. operation

Table 1: Life-cycle phases of international development projects.

and long-term goals. It should be eval- countries was based on the authors’ For each phase of the project, the

uated at the end of the project by a access to the international develop- respondents are asked to rate their

different set of criteria that are based ment projects in these countries but perception of the importance of the

essentially on the development impacts, can also be justified by the total volume success factors listed for the phase

the sustainability and the acceptance of assistance aid involved (US $1,894.6 (questions QI35–QI53). For the same

of the project achievements by the million in 2004, or 29.53% of total ODA factors, the respondents are also asked

stakeholders and the development com- disbursed for the 11 countries in South- to assess the extent these factors are–or

munity in general. East Asia), with Vietnam being the have been–actually present in their

As indicated by the research largest recipient of ODA in South-East project (questions Q35–Q53). By regress-

reviewed, the conditions required to Asia (US $1,768.8 million in 2004) and ing the project success measures to the

ensure the project management suc- Myanmar, one of the smallest. A 53- scores provided for these later ques-

cess in each life-cycle phase involves item questionnaire was used where the tions, the actual impacts of these fac-

the competencies and commitment respondents were asked to evaluate the tors on the success of the phases as well

of the concerned parties in carrying out success of their project using different as the overall success can be evaluated.1

the scope of the work of the phase, and approaches, and then assess the critical Thus, both the subjective judgment

other external enabling environmental success factors both on their perceived and a more objective assessment of the

conditions for the conduct of these importance and on the extent of their relative importance of the factors on

activities. As these conditions could presence in the project. the project success are obtained and

be extensive, the authors focus on the The overall success of the projects compared.

most common factors, based on their is first evaluated using the perceived Over 1,000 questionnaires were dis-

own experiences and field interviews judgment by the various key stake- tributed to the project managers and

with the project stakeholders. In addi- holders, such as manager and team staff members, officials at donor agen-

tion, since the end products of one members, funding and implementing cies, government agencies and INGOs

project life-cycle phase serve as inputs agencies, target beneficiaries and gen- in visits to their offices, and in work-

for the subsequent one, the success eral public (questions Q6–Q12). After- shops attended by them. Of the 374

in each phase provides favorable pre- ward, the respondents also evaluate the returned questionnaires, after discard-

conditions for the implementation of overall success of their project based on ing responses with missing data, 368

the remaining part of the project. The more specific criteria identified in the were usable. A preliminary analysis of

success criteria for one phase are con- model, such as visible impact on target the data collected reveals a broad and

ceptualized as part of the success factors beneficiaries, built capacity, reputa- relatively balanced representation of

for the subsequent phase. tion, sustainability of project results, the different sectors and types of stake-

Table 2 summarizes these criteria and chance of being extended as result holders in the sample: In Vietnam (296

and factors for the life-cycle phases of of success (questions Q30–Q34). These responses) the respondents come

international development projects. two sets of criteria correspond to mostly from agriculture, environmen-

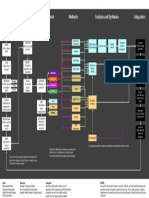

Figure 1 provides a comprehensive rep- the two dimensions of project success: tal, energy, social development, and

resentation of our proposed framework the perceived satisfaction by key stake- capacity building-reform-governance

that incorporates the identified criteria holders, and the quality of overall categories, while the respondents in

and factors for both project manage- intended results. The respondents are Myanmar (72 responses) represent the

ment success and project success into a also asked to evaluate the partial proj- INGO’s working with social development,

dynamic structure linking the life-cycle ect management success of each life-

phases of the international develop- cycle phase the project has gone

1Although one may argue that statistical analysis of Likert

ment projects. through. The criteria used include the

scale data is not rigorously tractable with classical multiple

quality of the outputs produced by regression (see, for example, Diallo & Thuillier, 2004, 2005),

the phases as well as the acceptance of this study follows the common “pragmatist” approach in

Empirical Validation these outputs by the key stakeholders business research of treating Likert scale data as interval or

“quasi-interval” measurements (Cooper & Schindler, 2001,

Survey Design (questions Q13–Q28). The traditional p. 234; Hofstede, 2001, p. 50; Pedhazur & Schmelkin, 1991,

In order to validate the model, a survey criteria of targets, time and costs are p. 28). Regression analysis was also commonly used in crit-

was conducted with internal and included in the success assessment in ical success factor research (for example, Andersen and

Jessen, 2000; Pinto & Slevin, 1989). In this study, to cross-

external stakeholders of both Official the implementing phase, which is con- check the results of regression analysis, multinomial regres-

Development Assistance (ODA) projects sistent with the common approach in sion analysis was performed on the same data following the

and international non-governmental the literature (Belassi & Tukel, 1996; approach taken by Diallo and Thuillier (2004, 2005), with

essentially consistent results. We report here the classical

organizations (INGO) in Vietnam and Diallo & Thuillier, 2004; Pinto & Slevin, regression results that are straightforward and easier to

Myanmar. The choice of these two 1987). interpret.

March 2008 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj 77

PAPERS

Success Criteria and Factors for International Development Projects

Life-Cycle Phases Success Criteria Critical Success Factors

Conceptualizing • Addressing relevant needs of the right target group of • Clear understanding of project

beneficiaries environment by funding and implement-

• Identifying the right implementing agency capable and ing agencies and consultants

willing to deliver • Competencies of project designers

• Matching policy priorities and raising the interests of key • Effective consultations with primary

stakeholders stakeholders

Planning • Approval of, and commitment to, the project by the key • Compatibility of development priorities of

parties the key stakeholders

• Sufficient resources committed and ready to be disbursed • Adequate resources and competencies

• Core organizational capacity established for PM available to support the project plan

• Competencies of project planners

• Effective consultation with key

stakeholders

Implementing • Resources mobilized and used as planned • Compatible rules and procedures for PM

• Activities carried out as scheduled • Continuing supports of stakeholders

• Commitment to project goals and

• Outputs produced meet the planned specifications and

objectives

quality

• Competencies of project management

• Good accountability of resources utilization

team

• Key stakeholders informed of and satisfied with project

• Effective consultation with all stakeholders

progress

Closing/ • Project assets transferred, financial settlements completed, • Adequate provisions for project closing in

Completing and team dissolved to the satisfaction of key stakeholders. the project plan

• Project end outputs are accepted and used by target benefi- • Competencies of project manager

ciaries. • Effective consultation with key stakeholders

• Project completion report accepted by the key stakeholders.

Overall Project • Project has a visible impact on the beneficiaries. • Donors and recipient government have

Success • Project has built institutional capacity within the country. clear policies to sustain project’s activities

and results.

• Project has good reputation.

• Adequate local capacities are available.

• Project has good chance of being extended as result of

success. • There is strong local ownership of the

project.

• Project’s outcomes are likely to be sustained.

Table 2: Success criteria and factors for international development projects.

health-nutrition-population, and capac- alpha values, ranging from 0.89 to 0.95 are also confident that other key stake-

ity building-reform-governance proj- for the items covering overall success, holders assess their projects as equally

ects. In terms of responsibility, 28% of partial success, and the success factors’ successful. This general optimistic

the respondents are project managers, presence and importance. assessment of success reflects the

coordinators or directors; 47% are proj- impact of social desirability of develop-

ect team members; and the remainder Analysis of Findings ment projects over perceptions of their

are representing external stakeholders Overall, the respondents have a very success. The only exception here is the

(donors, local authorities and target positive judgment of the success of judgment of how the general public

beneficiaries). Reliability analysis for their projects (with average score above perceives the projects (average score of

the questionnaire yields high Cronbach’s 4.0 over a scale of 5; see Table 3). They 3.83, significantly lower than the others).

78 March 2008 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj

o Compatibility of o Compatible rules and

development priorities of procedures for PM

the key stakeholders o Consistent supports of

o Adequate resources and stakeholders

competencies available to o Adequate provisions for o Policy supports of donors

o Clear understanding of o Commitment to project

support the project plan project closing and recipient government

project environment goals and objectives

o Competencies of project o Competencies of project o Adequate institutional

o Competencies of project o Competencies of project

planners manager competencies

designers management team

o Effective consultation with o Effective consultation with o Strong ownership and

o Effective consultation with o Effective consultation

key stakeholders key stakeholders institutional commitments

primary stakeholders

CSFs CSFs CSFs CSFs CSFs

I. Conceptualizing II. Planning III. Implementing IV. Closing/Completing Project Success

o Resources mobilized o Financial settlements o Development impacts

o Need assessment report o Final project documents

o Activities carried out o Project completion report o Sustainability

o Project concept paper o Project agreement

o Outputs produced o Outputs and project assets o Recognition

o Short term work plans and transferred

M&E reports o Project team dissolved

SC SC

SC

o Addressing relevant o Approval of, and

o Project is sustained by local

commitment to, the project SC SC

needs of the right target institutional capacity

group of beneficiaries by the key parties o Resources mobilized and o Project assets transferred,

o Project’s impacts on

o Identifying the right o Sufficient resources used as planned financial settlements

beneficiaries are visible

implementing agency committed and ready to be o Activities carried out as completed, and team

o Project has good reputation

capable and willing to disbursed scheduled dissolved to the satisfaction

in donor’s community

deliver o Core organizational capacity o Outputs produced meet the of key stakeholders

o Project is recognized to

o Matching policy established for PM planned specifications and o Project end outputs are

have meaningful and

priorities and raising the quality accepted and used by

significant contributions to

interests of key o Good accountability of target beneficiaries

the development of the

stakeholders resources utilization o Project completion report

country

o Key stakeholders informed accepted by the key

o Project is extended into

of and satisfied with stakeholders

another phase

project progress

Project Management Success Project Success

Overall Project Success

Figure 1: Project life-cycle-based framework for international development projects management.

March 2008 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj

79

PAPERS

Success Criteria and Factors for International Development Projects

Success Judgment by Stakeholders Mean SD This lack of confidence in the public

perception suggests some possible

Q6 overall success perceived by the respondent 4.02 0.752 external communication problems that

Q7 success as perceived by manager 4.07 0.710 will emerge again in a later analysis.

Q8 success as perceived by implementing agency 4.08 0.738 A factor analysis performed on the

Q9 success as perceived by funding agency 4.08 0.717 success judgments of key stakeholders

Q10 success as perceived by team members 4.07 0.755

(questions Q7–Q12) indicates that the

Q11 success as perceived by target beneficiaries 4.05 0 .771

measurements of the success percep-

Q12 success as perceived by general public 3.83 0.925

4.09 tion of the project may be simplified by

grouping the respondents around three

Criteria-Based Success Evaluation by Life-Cycle Phases clusters: the management team, the

Conceptualizing phase agencies (both from recipients and

Q13 relevant needs 4.28 0.821 donor governments), and the target

Q14 right agency 4.23 0.701 group, including the general public.

Q15 matching donor priorities 4.26 0.782 The score of the groups could then

Q16 matching recipient country 4.20 0.825 be calculated by averaging the scores

4.24 0.596 of the variables within the groups.

Planning phase However, in this study, scores of all the

Q17 commitments of key parties 4.19 0.742 variables are simply averaged to obtain

Q18 sufficient resources 4.12 0.834 the overall subjective judgment of the

Q19 org. capacity 4.04 0.872 project success. This average is found

4.12 0.668 to correlate highly with the overall

success scores evaluated using more

Implementing phase

specific and objective criteria, with

Q20 resources mobilization 3.93 0.848

Q21 activities as scheduled 3.72 0.959 Pearson coefficients ranging from 0.488

Q22 output met specifications 3.98 0.869 to 0.576. (See Table 4.) The highest cor-

Q23 good accountability 4.03 0.781 relation (0.576 between the average

Q24 key stakeholders satisfied 3.97 0.805 success judgment and the Q34) also

3.93 0.692 indicates that the sustainability of proj-

ect results has larger bearing on the

Closing phase

perceived success judgment than other

Q25 end outputs accepted and used 4.15 0.798

Q26 financial dues settled 4.13 0.745 success criteria.

Q27 assets dissolved and transferred 4.04 0.808 The assessments by the respon-

Q28 completion report accepted 4.05 0.763 dents of the project management suc-

4.09 0.602 cess in the life-cycle phases are equally

positive. However, the respondents are

Table 3: Project success assessment, by stakeholders and at life-cycle phases.

less optimistic in assessing the success

Correlations Mean SD 1 2 3 4 5 6

1 Average success judgment 4.06 1

2 Q30 visible impact 4.21 0.706 0.516 1

3 Q31 institutional capacity 3.99 0.872 0.521 0.483 1

4 Q32 good reputation 4.04 0.763 0.530 0.440 0.484 1

5 Q33 good change for extension 4.01 0.861 0.488 0.404 0.469 0.518 1

6 Q34 sustained outcomes 4.07 0.812 0.576 0.553 0.586 0.515 0.564 1

Table 4: Correlation of success judgment and criteria-based assessment.

80 March 2008 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj

of the implementation phase. As Table 3 factors listed in our proposed model is further highlighted by the relatively

indicates, this phase has an average are indeed important to the success of low impact of effective consultations

score (3.93) that is significantly lower their projects: With a scale from 1 to 4, with other stakeholders: lowest in the

than the average success scores of the all the mean scores of the factors initiation and closing phases, second

other life-cycle phases. Also, most proj- exceed 3.4. (See Table 5.) Unlike the lowest in the planning phase and third

ects seem to have schedule problems, success criteria, the data do not indi- out of six factors in the implementation

as the mean score for the schedule cri- cate statistically significant differences phase.

terion (Q21 at 3.72) is significantly among the impacts of these factors in Table 5 only summarizes the per-

lower than all the other mean scores. the different life-cycle phases. Consist- ception of the respondents on the

The finding confirms the common per- ently throughout the life cycle of the importance of the factors listed in

ception of the development community projects, the competency factor was the model. In order to verify if these

that the implementation phase is when considered by the respondents as most perceptions truly reflect the real

projects exhibit most problems. It is not important. Although in different phases, impacts of the factors on the partial

surprising that after the implementa- this factor refers to the capacity to per- and overall success of the projects, the

tion phase, the closing phase is less form assigned functions of different respondents were also asked to evalu-

successful than the early stages of the players (designers in the first phase, ate the extent to which these factors

project life cycle. planners in the second phase, project were present in their project at the cor-

The success factors for the life-cycle manager and team in the last two responding phases. For each phase,

phases and for the overall project suc- phases), all respondents indicate that the regression analysis with the average

cess are first ranked according to their predominant influence in each of these success score of the phase as depend-

perceived importance to the project. phases is the capability of the internal ent variable and the presence of the

The respondents all agree that the active stakeholders of the projects. This factors in the phase as independent

Rank Rank (within

Importance of CSFs Mean SD (overall) a phase)

Conceptualizing phase

Qi35 understanding of environment 3.71 0.480 2 2

Qi36 effective consultations 3.47 0.590 16 3

Qi37 competency of project designers 3.71 0.484 1 1

Planning phase

Qi38 compatible development priorities 3.45 0.578 18 4

Qi39 adequate resources 3.61 0.552 7 2

Qi40 effective consultations with planning 3.48 0.631 15 3

Qi41 competency of project planners 3.64 0.536 5 1

Implementing phase

Qi42 adequate supports 3.63 0.506 6 2

Qi43 high motivation and interest 3.57 0.572 11 5

Qi44 adequate knowledge and skills 3.66 0.496 3 1

Qi45 adequate resources and support 3.57 0.552 10 4

Qi46 compatible rules and procedures 3.50 0.557 14 6

Qi47 effective consultations during implementing 3.58 0.556 9 3

Closing phase

Qi48 adequate provisions in project plan 3.46 0.583 17 2

Qi49 effective consultations during closing 3.43 0.575 19 3

Qi50 competency of project manager 3.55 0.542 13 1

Overall project success

Qi51 clear policies of donors 3.64 0.522 4 1

Qi52 local capacities 3.56 0.550 12 3

Qi53 strong ownership of project 3.58 0.557 8 2

Table 5: Perceived importance of critical success factors.

March 2008 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj 81

PAPERS

Success Criteria and Factors for International Development Projects

Standardized Beta Sig. Adjusted R2 Model Sig.

Dependent Variable: SP1

(Constant) 0.000 0.247 0.000

Q35 understanding of environment 0.247 0.000

Q36 effective consultations 0.302 0.000

Q37 competency of project designers 0.023 0.688

Dependent Variable: SP2

(Constant) 0.217 0.548 0.000

SP1 0.521 0.000

Q38 compatible development priorities 0.183 0.000

Q39 adequate resources 0.141 0.002

Q40 effective consultations with planning 0.075 0.105

Q41 competency of project planners 0.008 0.858

Dependent Variable: SP3

(Constant) 0.258 0.575 0.000

SP2 0.548 0.000

Q42 adequate supports 0.140 0.004

Q43 high motivation and interest 0.069 0.088

Q44 adequate knowledge and skills –0.039 0.397

Q45 adequate resources and support 0.083 0.080

Q46 compatible rules and procedures 0.010 0.846

Q47 effective consultations during implementing 0.136 0.005

Dependent Variable: SP4

(Constant) 0.000 0.543 0.000

SP3 0.639 0.000

Q48 adequate provisions –0.002 0.964

Q49 effective consultations during closing 0.129 0.007

Q50 competency of project manager 0.063 0.144

Table 6: Regression analysis of success factors.

variables can help determine the phases: In each life-cycle phase, the management team is most related to

impacts of these factors on the success influence of the success of the preced- success, the empirical evidence shows

of the phase. By taking into this analysis ing phase is always significant and, in that effective consultations are far

the average success score of the previ- fact, far exceeds that of other success more important in influencing the

ous phase as additional independent factors listed in the model. project success, at least for the interna-

variable, the hypothesis that the suc- However, the most surprising tional development projects. The mis-

cess of each phase also has influence observation from Table 6 is that the placement of attention on internal

over the success of the subsequent consultation factors (Q36, Q40, Q47, competency, rather than on external

phase can be tested. and Q49) turn out to have more influ- communication and participation, pro-

The results, summarized in Table 6, ence on the project management vides some explanations to the lack of

once again reconfirm the success success than most other factors, con- confidence shown by the respondents

factors developed in the model. Of trasting the findings from Table 5. The in their rating of how the public may

the 16 factors listed for the life-cycle only exception is in the planning phase, assess success of their projects (Q12,

phases, 10 have significant or moder- where external supports and resources Table 3).

ately significant impacts on the partial are slightly more important. This obser- This finding may also have far

project management success scores, vation is further emphasized by reaching practical implications:

and no factor has a significant negative the lack of statistical significance of the • In order to improve the project per-

beta coefficient in the regression competency factor in all phases. In formance, the advocates of the partic-

model. The analysis also confirms the other words, despite the conventional ipatory approach, which involves the

dynamic linkages of the partial project wisdom that the competence of the proj- stakeholders in the active participation

management success of the successive ect designers, planners and the project in the design, planning, implementing,

82 March 2008 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj

monitoring and evaluating develop- with its characteristics and inherent and INGO projects confirms the validity

ment projects, now have empirical project logic, allows for a clear picture of the model. It also illustrates the value

support; of the key project players involved and of the model in providing practical

• The focus of capacity building efforts their roles in the different phases of the insights on success and failure condi-

by donors, local governments and project, and a better understanding of tions of these projects. Empirical data

many implementing agencies on the conditions required in ensuring emphasize the importance of effective

training seems to be not well placed. project management and project consultancy and participation of the

This study would indicate that more success. stakeholders in all life-cycle phases.

efforts should be made in bringing the The framework may have important Although the survey was conducted

stakeholders together for the training practical implications. It emphasizes only in two selected countries in South-

activities to be effective and have the need to “start right” development East Asia, it is believed that the findings,

impacts on project performance. projects: the success of the early phases supported by the general conceptual

have strong impacts on later stages. framework, will have practical implica-

Conclusions Separating the success criteria and tions in managing international devel-

In this paper, a new framework is devel- conditions by life-cycle phases also opment projects in other developing

oped based on the previous empirical allows for more specific descriptions of countries. ■

and conceptual research on critical the conditions to be evaluated. For

success factors of projects, and adapted example, the competency factor com- References

with special consideration on the char- monly recognized in most research can Andersen, E. S., & Jessen, S. A. (2000).

acteristics and context of the interna- now be broken down into different sets Project evaluation scheme: A tool for

tional development projects. The key of skills and knowledge required by the evaluating project status and predict-

distinction here is the recognition of project designers, planners or imple- ing project results. Project

the different sets of success criteria and mentation team manager and mem- Management Journal, 6(1), 61–69.

conditions for the different stages of bers at different stages of the project. Baccarini, D. (1999). The logical

the project life cycle. For each phase Project management performance can framework method for defining project

of the project, the explicit list of the now be evaluated in each of the phases, success. Project Management Journal,

success criteria is developed based on and the framework presents a practical 30(4), 25–32.

analysis of the results typically expect- monitoring and evaluating tool that Baker, B. N., Murphy, D. C., & Fisher, D.

ed at the end of the phase to provide a can be used very early in the project life (1983). Factors affecting project suc-

result-based framework to evaluate the cycle, and thus facilitate timely correc- cess. In D. I. Cleland & W. R. King,

project management performance. tive actions. Because the framework (Eds.), Project management handbook

Meeting these success criteria requires supports the whole project life cycle, (pp. 902–919). New York: Van Nostrand.

favorable internal and external condi- this instrument can be useful to the

Belassi, W., & Tukel, O. I. (1996). A new

tions that include the high quality project manager during the implemen-

framework for determining critical

inputs from the preceding phase as well tation, but also to the designers, plan-

success/failure factors in projects.

as other factors that are derived from ners and external reviewers who are

International Journal of Project

an understanding of the activities involved with the project at earlier

Management, 14(3), 141–151.

required for, and the parties involved stages. The evaluation of the critical

in, the phases. The dynamic linkages success factors at each stage will help Cleland, D. I., & King, W. R. (1983).

between the criteria and factors in suc- forecast the future status and predict Systems analysis and project manage-

cessive phases provide a more solid project results. More important from a ment. New York: McGraw-Hill.

conceptual foundation to evaluate the practical standpoint, the results clarify Coleman, G. (1987). Logical framework

project’s current and future status, the weak areas needing special atten- approach to the monitoring and evalu-

because the different activities, players, tion and support for successful com- ation of agricultural and rural develop-

deliverables and environments at the pletion. On the other hand, the vast ment projects. Project Appraisal, 2(4),

various project phases necessitate dif- diversity of international development 251–259.

ferent conditions for success. projects creates some limits on the Cooke-Davies, T. (2002). The “real”

By focusing on international devel- practical application of the model: success factors on projects.

opment projects, the proposed frame- the success criteria and factors may International Journal of Project

work helps fill the knowledge gap in the need to be further adapted and refined Management, 20, 185–190.

studies of this important project man- for specific categories of IDP projects. Cooper, D. R., & Schindler, P. S. (2001).

agement application area. The context The analysis based on the proposed Business research methods. Boston:

of international development projects, framework and a field survey with ODA McGraw-Hill.

March 2008 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj 83

PAPERS

Success Criteria and Factors for International Development Projects

Diallo, A., & Thuillier, D. (2004). The (Cahier de recherche working paper Wiggins, S., & Shields, D. (1995).

success dimensions of international no. 63). Center for Research on Economic Clarifying the “logical framework” as a

development projects: The perceptions Fluctuations and Employment. tool for planning and managing devel-

of African project coordinators. Pedhazur, E. J., & Schmelkin, L. P. opment projects. Project Appraisal, 10,

International Journal of Project (1991). Measurements, design, and 2–12.

Management, 22, 19–31. analysis: An integrated approach. Youker, R. (1999). Managing interna-

Diallo A., & Thuillier, D. (2005). The Mahwah, NJ: LEA Publishers. tional development projects: Lessons

success of international projects, trust, Pinto, J. K., & Mantel, S. J., Jr. (1990). learned. Project Management Journal,

and communication: An African per- The causes of project failure. IEEE 30(2), 6–7.

spective. International Journal of Transactions on Engineering

Project Management, 23(3), 237–252. Management, 37(4), 269–276.

Do Ba Khang is an associate professor in the

Fortune J., & White, D. (2006). Framing Pinto, J. K., & Slevin, D. P. (1987). School of Management, Asian Institute of

of project success critical success fac- Critical factors in successful project Technology, Bangkok, Thailand. He completed

tors by a system model. International implementation. IEEE Transactions his first master’s degree in mathematics from

Journal of Project Management, 24(1), on Engineering Management, 34(1), the Eotvos Lorand University in Budapest,

53–65. 22–27. Hungary, and holds a MSc and a Dr. Tech. Sc. in

Gasper, D. (2000). Evaluating the “logi- Pinto, J. K., & Slevin, D. P. (1989). industrial engineering from the Asian Institute

cal framework approach” towards Critical success factors in R&D proj- of Technology, Thailand. His current research

learning-oriented development evalu- ects. Research Technology interests focus on the adoption of project man-

ation. Public Administration and Management, 32(1), 31–35. agement practices in developing countries in

Development, 20, 17–28. Project Management Institute (PMI). Asia. He provides consulting services to various

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s conse- (2004). A guide to the project manage- international bodies, governmental agencies,

quences (2nd ed.). London: Sage ment body of knowledge (PMBOK® and nongovernmental organizations in the

Publications. guide) (3rd ed.). Newtown Square, PA: region.

Kwak, Y. H. (2002, September). Critical Author.

success factors in international devel- Sayles, L. R., & Chandler, M. K. (1971). Tun Lin Moe holds a MA in business communica-

opment project management. Paper Managing large systems. New York: tion and management from the University of the

presented at the CIB 10th International Harper & Row. Thai Chamber of Commerce and a PhD in devel-

Symposium Construction Innovation & United Nations Development opment administration from National Institute

Global Competitiveness, Cincinnati, Programmes (UNDP). (2004). Human of Development Administration, Thailand. He

Ohio. development report 2004. New York: was appointed a postdoctoral fellow at the

Liu, A. N. N., & Walker, A. (1998). UNDP. Asian Institute of Technology, Thailand, and

Evaluation of project outcomes. Westerveld, E. (2003). The project Karlsruhe University, Germany. He has more

Construction Management & excellence model: Linking success cri- than 7 years of teaching experience in degree

Economics, 16, 109–219. teria and critical success factors. programs at internationally accredited universi-

Locke, D. (1984). Project management. International Journal of Project ties in Thailand. He also has more than 7 years

New York: St. Martins. Management, 21, 411–418. of work experience in an international develop-

Martin, C. C. (1974). Project manage- White, D., & Fortune, J. (2002). Current ment agency, a philanthropy organization, and

ment. New York: St. Martins. practice in project management: An business organizations. He is currently study-

Pallage, S., & Robe, M. A. (1998). empirical study. International Journal ing in a master’s degree program in public

Foreign aid and the business cycle of Project Management, 20, 1–11. policy at Pennsylvania State University.

84 March 2008 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj

View publication stats

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- XXX Impact of The Perceived RiskDocument16 pagesXXX Impact of The Perceived RiskDuy KhánhNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- PSYCH 610 GUIDE Real EducationDocument21 pagesPSYCH 610 GUIDE Real Educationveeru31No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance SheetsDocument97 pagesSustainable Livelihoods Guidance SheetsMurshid Alam SheikhNo ratings yet

- Nov 4Document43 pagesNov 4Faith Cerise MercadoNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- 12 Integration: ObjectivesDocument24 pages12 Integration: ObjectivesQwaAlmanlawiNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- NCM113 Lec FinalsDocument17 pagesNCM113 Lec FinalsBethrice MelegritoNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- 09.01.01.07 KNA Supplier Quality Manual Rev 0Document22 pages09.01.01.07 KNA Supplier Quality Manual Rev 0Marco SánchezNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Innovation Survey IndonesiaDocument21 pagesInnovation Survey IndonesiadarlingsilluNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Structural and Mechanical Electrical Plumbing Work Project of Hotel Patra CirebonDocument27 pagesStructural and Mechanical Electrical Plumbing Work Project of Hotel Patra Cirebontitah emilahNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Chap 7 Sampling Probability - StudentDocument54 pagesChap 7 Sampling Probability - StudentLinh NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Essentials To Statistics 5th EditionDocument4 pagesEssentials To Statistics 5th EditionAudrey KwonNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Oral Presentations RubricDocument1 pageOral Presentations RubricMohd Idris Shah IsmailNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Rock Music and Aggression PDFDocument9 pagesRock Music and Aggression PDFPsicosocial ReneLunaNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Behavioural AssessmentDocument5 pagesBehavioural AssessmentKranthi Ranadheer100% (1)

- Boxplot - ActivityAnswerKeyDocument6 pagesBoxplot - ActivityAnswerKeyGourav SinghalNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- How To Use ChatGPT To Create A Research InstrumentDocument7 pagesHow To Use ChatGPT To Create A Research InstrumentewNo ratings yet

- GST's Effect On Start-Ups: TOPSIS Approach On Compliances, Cost and Tax FactorsDocument9 pagesGST's Effect On Start-Ups: TOPSIS Approach On Compliances, Cost and Tax FactorsarunNo ratings yet

- TVL Students of TcitsDocument9 pagesTVL Students of TcitsIs Mo0% (1)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Time: 3 Hours Maximum Marks: 100 Note: Attempt Questions From Each Section As Per Instructions Given BelowDocument2 pagesTime: 3 Hours Maximum Marks: 100 Note: Attempt Questions From Each Section As Per Instructions Given BelownitikanehiNo ratings yet

- Definition Sources and MethodologyDocument53 pagesDefinition Sources and MethodologyDuhreen Kate CastroNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Tef Impact Report 2022Document164 pagesTef Impact Report 2022KIEFFOLOH BENJAMINNo ratings yet

- HESPISDocument8 pagesHESPISShivarajkumar JayaprakashNo ratings yet

- KBPATcaseDocument19 pagesKBPATcaseCristyl Vismanos GastaNo ratings yet

- 8614 Assignment No 1Document16 pages8614 Assignment No 1Noor Ul AinNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- MULE Design Research Process Model v2Document1 pageMULE Design Research Process Model v2Nur Ahmad FurlongNo ratings yet

- PBB in MauritiusDocument7 pagesPBB in MauritiusnewmadproNo ratings yet

- Cariogram - A Multifactorial Risk Assessment Model For A Multifactorial DiseaseDocument10 pagesCariogram - A Multifactorial Risk Assessment Model For A Multifactorial DiseaseFrancisco Bustamante VelásquezNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Outline DefinitionDocument7 pagesResearch Paper Outline Definitionfzhw508n100% (1)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- De-Escalation TechniquesDocument26 pagesDe-Escalation TechniquesCarolina PradoNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)