Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Property Transcriptdocx

Uploaded by

Prince Dela CruzOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Property Transcriptdocx

Uploaded by

Prince Dela CruzCopyright:

Available Formats

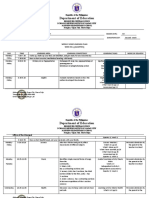

PROPERTY

Lecture By Dean Navarro

Transcribed By Bjone Favorito

Immovables………………………………………………………………………………….. 2

Movables……………………………………………………………………………………... 3

Public Dominion……………………………………………………………………………. 3

Ownership…………………………………………………………………………………… 5

Hidden Treasures………………………………………………………………… 7

Right of accession………………………………………………………………… 9

Accession with co-owners………………………………………………………. 13

Alluvion…………………………………………………………………………… 15

Usufruct……………………………………………………………………………………… 17

Rights of the Usufructuary……………………………………………………… 17

Obligations of the Usufructuary………………………………………………. 19

Extinguishment of Usufructuary………………………………………………. 21

Easments……………………………………………………………………………………... 23

Kinds of Easments……………………………………………………………….. 23

Modes of Acquiring Easments…………………………………………………. 24

Rights and Obligations of the Dominant and Servient Estate……………... 25

Modes of Extinguishment of Easements……………………………………… 25

Legal Easements…………………………………………………………………. 26

Right of Way…………………………………………………………… 26

Party Wall………………………………………………………………. 27

Light and View………………………………………………………… 28

Other Legal Easments…………………………………………………. 29

Nuisance……………………………………………………………………………………… 30

Public and Private Nuisance……………………………………………………. 31

Nuisance Per se and Per Accidens……………………………………………… 31

Remedies against Nuisance……………………………………………………… 32

Modes of Acquiring Ownership…………………………………………………………… 34

Occupation…………………………………………………………………………. 34

Intellectual Creation……………………………………………………………… 34

Donation…………………………………………………………………………… 37

Types of Donation……………………………………………………… 37

Inter Vivos and Mortis Causa…………………………………………. 38

Persons who may Give or Receive a Donation……………………... 39

Form for Valid Donations……………………………………………… 40

Things that may be Donated…………………………………………… 41

Reversion…………………………………………………………………. 41

Revocation and Reduction……………………………………………… 42

CAVEAT: Co-ownership and Possession (Art.484 to 561) not included

IMMOVABLE PROPERTIES

In the Mindanao Bus Company case, sabi ng SC dun: the industry is not carried on in this building

where the repair shop is located. The transportation business is carried on outside, not here. That is the

reason why the court said that the repair equipment there should not be considered as immobilized but

remain as personal property.

Can the parties agree that a certain machinery which has been installed by the owner of the

tenement for an industry or works which will be carried on in that building and which tend to meet

directly the needs of said industry or works, to treat this machinery as personal property? Subject them to

a chattel mortgage? Is that allowable? YES. The principle of estoppel will apply. Although the machinery

in the building, when installed by the owner and tend to meet the needs of the industry or works and

carried on in that building, if the parties agree to treat the machinery as chattel, and enter into a chattel

mortgage, neither of them will be permitted to question the validity of the chattel mortgage later on, on

the ground that the subject was actually a real property.

In number 6 of Art.415, the law deals with animal houses, pigeon houses, fish ponds and other

breeding places of a similar nature in case the owner has placed them or preserves them with the

intention to have them permanently attached to the land. The animals in these places are included. So, if

there is a pigeon house permanently attached to the land, the pigeons are also considered real property.

Of course pigeons sometimes fly around, or in the case of fish ponds, if you happen to have bangus, the

bangus are also considered real property, immovable even if they are swimming around. For purposes of

sale, however, these should be considered as movable property. So if you enter into a contract of sale of

the bangus in your fishpond, that’s not a sale of real property but considered sale of personal property. Or

if you donate the bangus to a certain individual, that should not be considered a donation of real property,

but a donation of personal property, otherwise you would need to execute a public document both for the

donation and the acceptance.

Fertilizers actually used on a piece of land. What about insecticides? Same rule should apply.

Then you have mines, quarries or slag dumps, while the matter thereof forms part of the bed and

waters, either running or stagnant. The waters referred to here are natural waters. So if you have several

drums of water which you keep in your yard, because in some areas water is getting scarce, the water in

those drums which you have earlier collected cannot be considered as covered by number 8 of Art.415 –

mga waters dito, mga waters in rivers, in lakes, or in lagoons – natural waters.

Docks and structures, which are although floating, are intended by their nature and object to

remain at a fixed place on a river, lake or port. A question was asked regarding this: there was a barge

which was at a fixed place. Basta nasa fixed place, consider it as real property even if it’s floating. For

example NAPOCOR and some other private companies have these power barges which supply electricity

to certain island provinces. So they are usually docked along the shore or a port and they remain there for

a considerable period of time – they are considered as real property. Yung floating restaurant dyan sa may

Transcribed By: Bjone Favorito Page 2

reclamation area, it’s floating but it remains at a fixed place, thus should be considered a real property.

But of course, if it’s actually a boat which takes on passengers and go on a cruise of Manila Bay

while dinner is served, I don’t think you can consider that as real.

Lastly, you have contracts for public use or servitudes and other real rights over real property.

MOVABLE PROPERTIES

Certain real properties are, by special provision of law, also considered as movable property.

Very good example are growing crops – under the chattel mortgage law, as well as under the civil code

provisions on sales, they are considered personal property. While they are still growing on the soil, sabi

ng SC in Sibal vs. Valdez, it’s a mobilization by anticipation. In other words, the law already anticipates

their subsequently becoming movable. When would that happen? When they are actually gathered, so

even before they are gathered, there is mobilization. That’s why they can be the subject of a chattel

mortgage.

Forces of nature which are brought under control by science. Nuclear power, wind power,

electricity – these are considered movable property.

Shares of stock in any corporation – these are considered personal property regardless of the fact

that the corporations in which these shares are held has real property or even if all of the assets consists of

real property. The shares of stock shall always be considered as personal property.

PUBLIC DOMINION

Art.420 – Properties considered as Public Dominion: those intended for public use and those

intended for public service or for the development of national wealth.

Properties intended for public use – roads, streets, parks. A property is considered, according to

the court, for public use within the meaning of the civil code, if it is open indiscriminately to the public. In

other words, anyone can go there and use it. Like streets – anyone can use it; it is open indiscriminately to

everyone.

Properties of public dominion area subject to certain special rules – another important thing we

have to remember. They cannot be made the subject matter of contracts. They cannot be sold, nor leased.

They cannot be acquired by prescription. They cannot be attached and sold at a public auction to satisfy

any judgement. They cannot be even burdened with an easement. You cannot even register them, have

them titled in your name under the torens system, and if a title is issued, that’s not a valid title.

The Government has property of two types: Of Public Dominion and Patrimonial Property. With

respect to the Patrimonial, just like any other ordinary private property, it can be the subject of contracts.

Property of Public Dominion, as long as it remain as such, is subject to the special rules we just

Transcribed By: Bjone Favorito Page 3

mentioned. Is it possible to convert Public Dominion to Patrimonial? The answer is YES, it is possible.

How can that be done? Will the mere fact that property of public dominion is no longer actually being

used for public use or is no longer actually being devoted for public service automatically converts it to

patrimonial property? The answer is NO, it will not. There must be a formal declaration by the executive

or legislative of such conversion, otherwise the property remains property of public dominion.

With respect to property of political subdivisions, the conversion must be authorized by law. A

very good example is the Roppongi cases involving the property of the Philippines located in Japan which

were given to us by way of reparation by the Japanese as part of the reparations agreement. Those

properties were originally intended for the use of our embassy but they were never used for that purpose.

After a long period of time, there was an attempt to sell these properties. The SC said: “the mere fact that

these properties in Japan have not been actually used for their original purpose does not automatically

convert these properties into patrimonial properties. They remain part of public domain, and

consequently are not available for private appropriation or ownership until there is a formal declaration

on the part of the government to withdraw it from being such. Abandonment cannot be inferred, it must

be definite.” On the part of local government entities, just like the state, their properties are subdivided

into public use and patrimonial. For property to be considered for public use, it must be open

indiscriminately to the public, otherwise it cannot be said to be for public use.

In some cases, however, the SC, in determining whether properties of a LGU should be

considered as public or patrimonial, opted to apply the special laws governing municipal corporations.

Thus, in the case of Zamboanga del Norte vs The City of Zamboanga, the SC said: “we cannot possibly decide

this case strictly along the lines and parameters set by the civil code in determining what properties are

for public and private.” This involves the creation of a new local gov’t carved out of a former political

unit. In that case, and in similar cases involving local gov’ts, the SC instead considered the use of the

property – whether it is for governmental purposes or not. As long as the property was used for

governmental purposes, it was considered public property. Still on this point, in the absence of clear

evidence as to the source of the funds used in acquiring the property which is currently being held by the

local government unit, the presumption is that the property came from the state - Salas vs Harencio and

similar cases. So, if an LGU is currently holding a property, but there is no clear showing as to the source

of the funds used to acquire the property or as to how it acquired the property, the presumption is that

the property or land actually came from the state and the LGU is holding it merely in trust for the state

for the benefit of the inhabitants of the locality. If that is so, those properties cannot be considered as

patrimonial property and the national legislature will be considered to have absolute control over these

properties.

In some cases decided by the SC, it has been made clear that LGUs cannot enter into contracts,

cannot even validly authorize by means of an ordinance, the awarding of contracts over certain streets in

favor of private individuals for purposes of having a flea market there. As long as the street remains a

street, it’s for public use and therefore it is beyond the power of the LGU to deal with by means of

contracts. In one case, the LGU authorized that a certain street be converted to a flea market. There was

an ordinance authorizing that. The court said that cannot be. What is clear from these cases is that: while

Transcribed By: Bjone Favorito Page 4

even under the Local Government Code, LGUs are allowed to withdraw certain streets, when no longer

necessary, from public use, they cannot do so without actually withdrawing the road from public use.

They will still maintain it as a street and, at the same time, operate it as a flea market – that cannot be

done. So in these cases sabi ng court “hindi pwede yan. As long as they have not been withdrawn from

public use, they remain property for public use and you cannot, at the same time, enter into contracts

with private individuals who intend to operate a flea market in that road. Kung gusto nyo, i-withdraw

nyo.” In other words, it will cease to be a street, and only after that can you deal with it as patrimonial

property but not while it is still a street.

You recall the ruling of the SC in Chaves vs PEA. There was this agreement between the PEA and

the AMARI, that AMARI would reclaim areas of the Manila Bay and, as payment, it will be paid with

reclaimed lands. Maliwanag na maliwanag, sabi ng SC “with respect to the reclaimed lands on freedom

islands around 157 hectares which are covered by titles in the name of the PEA, they are alienable lands

of the public domain. But they may only be leased, not sold, to private corporations. Of course, they may

be sold to Filipino citizens. With respect to the submerged areas, they are inalienable and outside the

commerce of man. Only after PEA has reclaimed them may the gov’t reclassify them as alienable and

disposable lands, if no longer needed for public service. The transfer of the submerged lands to AMARI is

also void since the Constitution prohibits alienation of our natural resources other than agricultural land

of the public domain.” Of course, there were many separate opinions filed in that case but just stick to the

main decision.

OWNERSHIP

Remember the traditional attributes of ownership. Generally the rights of an owner – The right to

use, right to the fruits, the jus abutendi – that should never be interpreted to mean the right to abuse, there

is no such thing. Jus abutendi simply means the right to consume the thing by its use. Right to dispose,

right to vindicate or recover. You also remember the limitations on the rights of ownership. These are

limitations which may come either from the state, in the exercise of its inherent powers, or imposed by

specific provisions of law like the provisions of the civil code dealing with easements. These may also be

limitations imposed by the person transmitting the property – if I am donating property to you, I may

impose on the deed of donation certain limitations on your use of the property.

In connection with the rights of ownership, you remember the doctrine of self-help under

Art.429. An owner or lawful possessor is allowed by law the use of such force as may be reasonably

necessary to repel or prevent an actual or threatened unlawful deprivation or physical invasion or

usurpation of his property. Only reasonable force should be used. The doctrine can be invoked only at the

time when there is an actual or threatened unlawful physical invasion, not thereafter. If the property has

already been taken by the third person, you are not allowed to use force to get it back. You must invoke

the aid of judicial authorities. One of the best examples would be the case of German Management and

Services Inc. Here was a land owner who wanted to develop his property and so he executed an SPA in

favor of German Mngt Services to develop the property. GMS went to the property and discovered that

Transcribed By: Bjone Favorito Page 5

certain individuals are occupying and cultivating the property. GMS used physical force to oust these

occupants and later on invoked the doctrine of self-help. Court said “that’s not proper, it is not disputed

that when they tried to enter the property, those occupants were already there cultivating the land for

some time. A party in peaceable quiet possession shall not be turned out by a strong hand, violence or

terror.” The doctrine can only be exercised and invoked at the time of actual or threatened dispossession.

When possession has already been lost, the owner must resort to judicial process for the recovery of his

property and cannot take the law into his own hands.

A little oxygen break at this point

The owner has the right to enclose his property with a fence, a wall or any other means. There is a

very beautiful case in this connection, I refer to Custodio vs CA. There was a property owned by a person,

and there was no fence around this property. So, some of his neighbours were passing through his land

to reach the public road. Later on, the property owner decided to enclose his property with a fence.

Consequently, his neighbours could no longer pass through, they had to take a more round-about route

to reach the street. They filed a complaint for damages. The court said “this is a case of damnum absque

injuria. The property owner was simply exercising a right explicitly granted to him by law – the right to

enclose his property with a fence. In the meantime, great inconvenience was caused to his neighbours

who now had to take a longer route to reach to street. It’s just too bad but obviously they do not have the

legal right to claim damages.” Please take note that when the case was decided, there was no easement

yet. It was only after the case was decided that the court said: an easement should be created but they

should pay indemnity. So, as long as there is no easement yet, you have the perfect right to enclose your

property with a fence. That’s very clear in art.430.

A property owner has the Jus Utendi – the right to use his property. But the right to use ones’

property must be exercised in such a way as not to injure others – Sic utere tuo ut alienum non laedas. In one

case, there were two adjoining properties. The owner of the higher property built thereon a certain

artificial bodies of water. There were artificial lakes, water pots, etc. Unfortunately, during bad weather,

some of these constructions were washed away and they fell to the adjoining lower estate. The lower

court dismissed the case, the SC said the case should be reinstated applying art.431. Obviously, the court

considered the construction of theses artificial bodies of water on the higher estate as something which

causes some damage or prejudice to the adjoining lower estate.

You also take note of the provisions of art.432 of the civil code, sometimes referred to as the

emergency doctrine. If you are the owner of a thing, the law says you have no right to prohibit the

interference of another person with your property, as long as the interference is necessary to prevent an

imminent danger and as long as the threatened damage or injury is much greater than the damage which

would arise to you from the interference with your property. In this connection, the view has been

advanced, to which I agree, that negligence on the part of the person interfering does not preclude resort

to the rule under 432. If, for example, while I was using my car, another vehicle, owned and driven by

Mr. X, careened into the street and slammed into a meralco post and started to billow with smoke, was

obviously on fire. Under this article, Mr. X, although was negligent, would have the right to interfere

with my property if I happen to have a fire extinguisher. I do not have the right to prohibit his

Transcribed By: Bjone Favorito Page 6

interference with the use of that extinguisher. His negligence does not preclude him from invoking the

rule under 432. Obviously, any possible damage which might be caused to me through the use of my fire

extinguisher is much less than the damage which would result from the complete burning of his car. So,

in that case, the requirements of 432 would clearly be met.

You just read art.433 and 434 – actual possession under claim of ownership raises a disputable

presumption of ownership. The true owner must resort to judicial process if he wants to recover his

property. And then, the requirement in an action to recover property is that: (1) the property must be

identified; (2) the plaintiff must rely on the strength of his own evidence, and not on the weakness of the

defendant’s claim - which is in accord with the rule that “he who alleges has the burden of proof”.

Art.435, on the other hand, is simply a restatement of the basic principle in Constitutional Law.

One of the inherent powers of the state is the power of eminent domain – property may be taken for

public use as long as there is payment of just compensation.

Art.436 is a restatement of the rule on police power. The moment the state exercises it’s police

power, then property rights must necessarily yield, and if property is taken or damaged or destroyed as a

consequence of police power, there is no right to any indemnity. The only indemnity you get is the

feeling of satisfaction that somehow you have contributed to the common good.

I call your attention to art.437. The owner of property is the owner not only of its surface, but of

everything under it. Of course, that does not necessarily mean that everything under the provision is to

be taken in its literal sense. If there are, for example, there are minerals under your land, that does not

belong to you, that belongs to our Kabalikat sa Kaunlaran – the State (Regalian doctrine). The question is:

Up to what depth will you be considered the owner of what is beneath your land? Does that extend up to

the middle of the earth? The rule of thumb is: it extends only up to such depth as you can still make use

of it. In a case decided by the SC, it would seem that it is quite deep, at least in the point of view of the SC.

I refer to NPC vs. Ibrahim where there was a property owner and, unknown to him, the NPC has

constructed a tunnel passing beneath his land because the NPC was drawing water from Agus river. So

the property owner was not aware of the tunnel. It was only much later that he found out.

Hidden Treasures

What is considered as Treasure? The Law Defines in Art.438 - it is any hidden AND unknown

deposit of money, jewellery or other precious object, the lawful ownership of which does not appear. In

other words, hindi alam kung sino ang may ari. If you see your neighbour one midnight, digging a hole

in a parcel of land near your house, and hiding a jar full of jewellery – that is not hidden treasure. Alam

mo kung sino ang nag baon. The lawful ownership must not appear.

The law enumerates money, jewellery or other precious objects. Applying the ejusdem generis rule,

that should be limited to things of similar nature. Therefore, this does not include mineral deposits or oil.

Pag aari yan ng ating Kabalikat sa Kaunlaran – the State. What is the rule with respect to hidden treasure? It

belongs to the owner of the land, building or other property in which it is found. If it is found by another

person, in other words, somebody other than the owner of the property AND by chance: you have the 1/2

Transcribed By: Bjone Favorito Page 7

rule (50-50). Half will belong to the owner, the other half to the finder. If, however, the finder happens to

be a trespasser, he is not entitled to any share.

The law requires that the finding must be "by chance". In other words, this would usually mean,

and in the traditional meaning ascribed to this phrase is, that the finding was not intended. Totally not

expected, the finder was not looking for the treasure.

Supposing that a man has been given the usufruct of a parcel of land by his friend, then there was

an old man who gave him what appeared to be an old map and the old man told him that on a part of

that property, there is treasure buried by pirates a long time ago. And so this usufructury, believing what

was told to him by the old man, digs at the precise spot indicated by the old map. And true enough, he

finds hidden treasure. Will he be entitled to any share of the treasure? Will his finding be considered as a

finding by chance? If you go by the traditional view, then it would seem that it would not fall under that

category because he intentionally looked for the treasure. But I think this logic and good sense in the view

advanced by others, according to them, when the law says "by chance", that should be interpreted to

mean "by a stroke of good fortune".

Let me put it this way: a lot of people have been engaged, all over the Philippines, in the search

for the so-called "Yamashita Treasure". Even books have been written about the search for this treasure. A

lot of people have engaged in diggings, have spent millions to finance these excavations. But a lot of them

were not able to locate any treasure at all. Even if you look for treasure, there is no guarantee, even if you

are using an old map, that you will be able to find one. In that sense, if you do find treasure, your finding

could be considered as "by a stroke of good fortune" and in that sense, it can be considered as "finding by

chance".

If the finder was precisely employed by the owner of that land to look for treasure there, the

finder will not be entitled to any share under Art.438. His remuneration will depend on his contract or

agreement with the land owner as to how the treasure will be shared or as to his compensation for the

work which would be undertaken.

Transcribed By: Bjone Favorito Page 8

RIGHT OF ACCESSION

The General Rule contained in Art.440: "If you are the owner of property, by right of accession,

you are also entitled and own everything which is produced by the property, or which is incorporated

with that property, or which is attached to that property, either naturally or artificially. The owner has the

right, by accession, to everything produced, incorporated or attached to that property.

There are various kinds of accession. You have Accession Discreta - the right, given to the owner,

to everything which is produced by the property. This is divided into the three types of fruits: Natural

fruits, Industrial fruits and Civil fruits. Natural fruits are the spontaneous products of the soil, and other

products of animals. Animal manure - that's natural fruit. Mushrooms not cultivated, those that just

sprout in the fields especially after a thunderstorm the previous evening - those can be considered as

spontaneous products of the soil. Industrial fruits, on the other hand, are those which are produced by

lands through human labor and cultivation. If you are talking of mushrooms which are produced by a

farm, they are cultured, that would be industrial rather than natural. Civil fruits - rents, the price of leases

of lands and other property, life annuity and other similar income.

Then you have Accession Continua - the right, given to the owner, to everything which is

incorporated or attached to his property either naturally or artificially.

With regard to immovable property, you have: (1) Accesion Industrial, which covers buildings,

plantings, sowing, and you have; (2) Accesion Natural, which includes Alluvion, Avulsion, change of river

bed, formation of islands, etc.

With regard to movable property, you have (1) Adjunction/Conjunction,

(2) Commixtion/Confusion and (3) Specification.

To the owner belongs all of the fruits. Do not forget, however, the rule under Art.443, a very

important rule, that he who receives the fruits have the obligation to reimburse the expenses made by

another person in their production, gathering and preservation. Please take note that in 443, the law does

not distinguish between people or persons who are in good faith and persons in bad faith. It applies to

everyone. You might have been in bad faith but as long as you spent for the production, gathering and

preservation of the fruits, the owner who is able to get that possession is obligated to reimburse you for

the expenses which you incurred. Please take note also that the article would not apply if the fruits have

not yet been gathered. So if the fruits are still ungathered, you don’t apply 443. Consequently, if you

happen to be in bad faith and you have not yet gathered the fruits when the lawful owner or possessor

recovers the property from you, you don’t apply 443. You simply lose all of these fruits, applying the rule

with respect to possessors in bad faith as well as planters and sowers in bad faith. He who is in bad faith

loses everything that he has built, planted or sown.

Art.445 tells us when these rules on accession, with respect to immovable property, would apply

and when they would not. The law says “whatever is built, planted or sown on the land of another,

together with the improvements and repairs made thereon, shall be belong to the owner of the land.” If I

build, pant or sow on my own land, therefore, these rules on accession would find no proper application.

Transcribed By: Bjone Favorito Page 9

You apply these rules if it was on the land of another. Because if it was the owner of the land himself who

builds, plants or sows, there is no question, he is really the owner of everything. As a matter of fact, there

is a presumption under Art.446 that everything or all works of sowing and planting are presumed to

have been made by the owner and at his expense. Of course, that is a disputable presumption, but a

presumption just the same.

What is the scenario in Art.447? Here is a land owner who decides to build on his property using

the materials of another person. I have a parcel of land, I build a house there, or any other thing, but I use

your material. There are always two possibilities: either I am in good faith or in bad faith. Good faith – if I

thought that I had the right or owned the materials. Bad faith – if I knew that you were the owner of those

materials, and despite that knowledge, I still used them. If I am in good faith, what is my obligation? The

law says I should pay their value – that is fair and square. Can I be held liable for damages? The answer is

NO, because precisely, I was in good faith. I simply have to pay the value of the materials owned by you.

If I am in bad faith, of course I have to pay the value of the materials PLUS damages intended to penalize

me for my bad faith. What would be the rights of the owner of the materials? The law says you can

remove your materials if it is possible to do so without injury to the work constructed. If it is possible to

remove your materials without injury, that means it’s not really a case of attachment because it’s possible

to remove without injury to the plantings, construction or works. If I am in bad faith, however, the law

says you can remove your materials in any case, aside from your right to recover damages. So if good

faith – limited right of removal on your part.

Scenario contemplated by Art.448: here the law contemplates a situation where there is a land

owner and somebody builds, plants or sows on his property. Again, we have to determine whether the

builder, planter or sower is in good faith or in bad faith. The land owner also, because the land owner can

be in bad faith. When? If he knew that somebody was building on his property and he permitted/allowed

it to continue (Sige lang, mag tayo ka dyan. Tapos ka. After a while, akin yan). Bad faith ‘yon. If he was not

aware – good faith. The builder, planter or sower, on the other hand, would be in good faith if he is not

aware of any defect or flaw in his title or mode of acquisition. The builder thinks he owns that land, or he

thought he had the legal right to build thereon. If he is aware that he has no legal right to build on that

property, but he built, planted or sown just the same, he would obviously be in bad faith. What would be

the respective rights? Assuming both parties are in good faith, the rights would be as follows: The land

owner can appropriate what has been built, planted or sown on his land. Of course, he has to pay proper

indemnity to the builder, planter or sower. In the case of building and planting, the land owner also has

the option of selling the land, occupied by the building or planting, to the builder or planter. He cannot,

however, avail of that option (yung “ask the builder or planter to buy the land”) if the value of the land is

considerably more than the value of the building or planting. Please take note, the law uses the phrase

“considerably more”. If the value of the land and the value of the building or planting are more or less the

same, or if the difference in the value is not too much, then the land owner is not precluded from availing

of that option. Kase dapat ang difference ng value must be considerably more than the value of the

building or planting. In that case, they can simply enter into a lease agreement. If they cannot agree on

the terms of the lease, the courts shall fix the terms thereof according to Art.448.

Transcribed By: Bjone Favorito Page 10

Please take note that 448 distinguishes between the planter and a sower. Obviously parehong nag

tatanim yan. What’s the difference? You are a sower if what you actually sow is something that will not

produce fruits for a long period of time – rice, for example. Sabi nung kanta “planting rice is never fun” but

actually pag dating sa 448, it’s not planting rice, it’s sowing rice. Because once you harvest, you’ll have to

sow again. Sower ka nyan. But if what you plant is something which will last for years and continue

producing fruits year after year, you are not a sower, you are a planter. Halimbawa, nag tanim ka ng punong

manga or coconut or whatever, that’s a case of planting. Because what you have planted will last for years

and continue producing whithout having to re-plant them. If what are involved are bananas, what are

you? Ordinarily I would say that you should be considered merely a sower, not a planter because the

ordinary way of getting the fruits is by cutting down the trunk. Pag bumagsak na, tsaka mo kukunin yung

mga bunches of bananas. Although some areas in South America, yung mga large banana plantations,

hindi daw ganon. They simply get the bunches of bananas and they are able to produce fruits for quite

some time.

Land owner has the right to appropriate, but he must pay the proper indemnity. What is the

indemnity? Supposing that the builder spent 500,000 when he built, but at the time when the land owner

exercises his option to appropriate, the building was already worth 5 million. What is the amount which

would constitute the proper indemnity? The Supreme Court has already decided that point. It is the

market value at the time when the indemnity is to be paid. So in that problem, although only 500,000 was

spent, since the property at the time when the indemnity is to be paid, the property was already worth 5

million, it is the latter which should be paid by the land owner. If the land owner decides to appropriate,

he has to pay the indemnity, and prior to such payment, the builder has the right of retention. If you are

the land owner and I am the owner, and we are both in good faith. I built on your land a building, you

informed me that your option is to appropriate the building. So, the price of indemnity, let’s say, is 10

million. Prior to your payment of 10M to me, I have the right to retain the building and to continue

occupying your land. That is the right of retention given by law to me. What is the purpose? To insure

that I will be paid properly the indemnity due to me.

Supposing that during this period of retention, while you have not yet paid me the indemnity,

nag hahanap ka pa ng perang pambayad sakin, the building is lost because of caso fortuito, tinamaan ng kidlat at

nasunog completey. What’s the net effect? Sorry nalang ako, I lose my right of retention because you are

not obligated, as land owner, to pay for buildings or improvements which have already ceased to exist.

So wala na, no more right of retention. During the period of retention, can the land owner demand from

the builder the payment of rent? Lupa ko yan e, I am deprived of the use of my property. The answer is

NO. As long as there is a right of retention brought about by the earlier exercise of the land owner of the

option to appropriate, he (the builder) cannot be compelled to pay rent. Why? Because if he is required to

pay rent, that will damage or negate his security for the payment of the indemnity.

Supposing that the property or building which I constructed in good faith on your land is

producing fruits. Let’s say that portions are being leased or rented out to third persons who are paying

me rent during the period when I have the right of retention. Who is entitled to the rentals being paid by

the tenants? Can these rentals be offset with the indemnity do to me? In one early case (Ortiz vs Cayanan)

Transcribed By: Bjone Favorito Page 11

which involved possessor in good faith who has a right of retention because the indemnity have not yet

been paid, during the period when he had the right, a detour was constructed through the property kase

one highway was being constructed and in the meantime, vehicles had to take a detour through the

property and tolls were collected. The question is, can the tolls collected by the possessor be offset or

compensated with the indemnity due to him? Supreme Court said YES. In other words, the right of

retention in that case is not merely a security but rather a way for the extinguishment of the obligation to

pay indemnity.

In some other cases, Pecson for example, sabi ng SC hindi pwede. If fruits are collected by the

builder in good faith during the period of right of retention, these fruits cannot be compensated with the

indemnity due him. Why? Because he is the one entitled, as a consequence to his right, to the possession

and tenancy of the property. He is also entitled to these fruits. So there can be no compensation of the

fruits and indemnity for the simple reason that they are both due and belong to him. Admittedly, I could

sense a certain ambivalence on the part of court decisions. One reason why, according to some decisions,

the builder in good faith is no longer entitled to the fruits during the period of retention is because under

the law on possession, the moment the builder becomes aware that he is not really the owner of the

property or there is a defect in the mode or title of his acquisition, then strictly speaking, he is no longer

in good faith. And from that moment on, he is not entitled to the fruits. That’s the basis of SC decisions.

But personally, I think that the better view is that he would still be entitled. In other words, as long as he

builds in good faith, he cannot be deprived of the rights pertaining to a builder in good faith, one of

which is the right of retention even if at some point he becomes aware that there is a defect in his title.

And the right of retention, I submit, necessarily implies tenancy and continued possession. As such, he

should still be entitled to the fruits and there can be compensation between the fruits and the amount of

indemnity due to him.

The option is given to the land owner, not to the builder. It is the land owner who decides

whether he will appropriate what has been built or planted or whether he will ask the builder or planter

to buy the land. That option is given to him. The builder cannot compel the land owner to simply sell the

land to him or at least the portion thereof occupied by his building. Why is the option given by law to the

land owner? In a case, the SC clearly says: because the right of the land owner is older.

Can the land owner simply refuse to exercise either of the option under Art.448? He does not

want to appropriate the building, sabi nya “Ayoko nyang building mo, ano gagawin ko, ampangit nyang bahay

mo”, neither does he want to sell the land occupied by the building. In short, he simply tells the builder

“Lumayas ka, tanggalin mo yang building mo dyan, dahil ‘di mo lupa yan, lupa ko yan.” Can the land owner do

that? The answer is: he cannot just refuse to exercise his option and simply ask for the removal of what, in

good faith, has been built or planted on his land. The options are limited to those in Art.488.

But supposing that the land owner avails or elects the option of selling his land and the value of

the land, let’s assume further, is not considerably more than that of the building. The builder, however, is

unable to pay. Kahit na sunugin mo yung builder, wala ka maamoy na pera. Wala syang pambayad dun sa land.

Sabi ng SC: if that is the case, then the land owner can ask for the removal of the building. If, having opted

to sell his land, and assuming the value is not considerably more than that of the building, the builder is

Transcribed By: Bjone Favorito Page 12

unable to pay, then that’s a situation where the land owner can actually ask for the removal of the

building. Any other remedies available to the land owner if that were the case? Of course, there is always

the remedy of simply entering into a lease. “Sige, di mo pala kayang bayaran, mag lease nalang tayo.” There is

also a third remedy, third option: The land owner can ask for a sale of both the land and the building, the

proceeds of the sale will be first applied to the value of the land. The rest, or any excess, will be delivered

to the owner of the house or the building.

Prior to the time that the land owner exercises his option of either appropriation or sale, the

builder would have been occupying the land of the land owner. Can he be required to pay rent for his

occupancy during that period prior to the exercise of the land owner of his option? The answer is YES, he

should be. The moment the land owner, however, exercises the option to appropriate; there arises the

right of redemption on the part of the builder, from that moment he cannot be compelled to pay rent. If

the land owner opts instead to sell the land to the builder, can rent be demanded in meantime? The

answer is YES, of course. The rent will have to be paid until such time when the property/land is in fact

acquired by the builder. Pag na acquire na nya yun, of course he is the owner already, he simply does not

have to pay rent anymore.

Accession with Co-owners

We said earlier that these rules on Accession on immovable property would not apply to a

situation where it is the land owner himself who builds or plants on his property kasi sabi natin, under the

law, “built, panted or sown on the land of another.” Kung sarili mong lupa, no application ‘to. Now, having

said that, it follows that if a co-owner of a property builds or plants on the property under co-ownership,

these rules would not apply. Because the co-owner is the owner of an ideal share of the whole. And, as a

matter of fact, under the law on co-ownership, a co-owner has the right to use the property under co-

ownership as long as he does not prevent the other co-owners from similarly using it. However, if the co-

ownership has already been terminated by a partition of the property and after the partition, it is

discovered that one of the previous co-owners has built on a part of a property which was later on

adjudicated to another co-owner, then the rules on Art.448 should apply. The previous co-owner who

had earlier built on the property under co-ownership, but a portion of whose building is discovered to

encroach upon the part adjudicated in the partition to the other co-owners, will have the rights of a

builder in good faith. For example, we are the two co-owners, and during the existence of the co-

ownership I built a building on that land. Later on, we agreed to partition the property, tapos ang co-

ownership by partition. Pagka partition naten, na-diskubre a few square meters of my building occupy the

part allotted to you under our partition agreement, 448 can be applied. I will be considered as a builder in

good faith.

The claim of good faith may be made by a successor in interest of the original builder. In one

case, a certain land, together with a building standing thereon, was purchased by a buyer. Later on, upon

re-survey of the land, it was discovered that a portion of the building encroached upon the adjacent

property. SC: The buyer in this case can invoke good faith and the provisions of 448 can apply.

Transcribed By: Bjone Favorito Page 13

To a certain extent, it’s quite amusing to remember some of the cases involved. In one case, can

you imagine, there was a couple who bought a lot from a subdivision. Usually, ang mga subdivision Lot

No. so-and-so, Block No. so-and-so. The time finally came when they decided to construct a house, so

punta sila sa subdivision. Tinanong nila yung representative of the subdivision developer “We are going to

construct already, saan nga ba yung lote na nabili namen?” “Ito ho” tinuro yung lote, so they constructed.

Anak ng tokwa, hindi pala yun yung lote. Nagkamali ng turo. Can they invoke the rights of a builder in good

faith? Of course, they can. By the way, even if the property involved is registered property, halimbawa

magkatabi yung lote naten, parehong may titulo, when property is titled, very precise ang description nyan ng

boundaries. (beginning at a point mark 1 on plan, 2000 mts from the llm etc ganyan, then north ganun-

ganun 70 degrees 40 minutes and whatever, to point 2..) Can you still claim good faith if the properties are

covered by a torens title? The answer is YES. Tandaan naten ang rason, baka matanong – because, if you are

an ordinary mortal person, you are not expected, unless you happen to be an expert in the science of

surveying, to know the precise boundaries of your property even if your property is covered by a torens

title. Kung surveyor ka – pwede, pero tayong mga ordinaryong mortals, anong malay naten kung nasan yang mga

north 70 degrees na yan? Although meron na ngayon mga GPS. Sa cellphone lang meron nyan e, sasabihin sayo

kung nasaang lugar ka, north ganito, eksakto, accurate to within 5 meters. Meron nga mga GPS na kinakabit sa

kotse, may nag sasalita “turn right after 100 meters”, but even then, I submit, the rule still applies. Unless

you are an expert in the science of surveying, you should not be held accountable for a mistake, so pwede

parin ang good faith. Pero ibang usapan naman kung halimbawa, I built on a lot in Manila. May nakita akong

bakanteng lote, nagtayo ako dun. Nung sinita ako ng may ari, sabi ko “ay ganun ba? Pasensya, akala ko lote ko ito

e” e wala naman ako titulo maskiano. Ang pagaari ko nasa Quezon city, wala akong property sa Manila, can I

claim good faith? NO, I should not be allowed to claim. My mere assertion that I thought I had the legal

right to build on the property is obviously a vagrant assertion. Why vagrant? Because it has no visible

means of support. So hindi pwedeng vagrant assertion.

Supposing that the builder is in bad faith – he loses everything, he becomes liable for damages.

The land owner can demand that you buy his land regardless of the value. No restriction that it should

not be considerably more – wala yung mga ganung restriction. Basta in bad faith ka, bilhin mo yung lupa ko.

Kung ang building mo is worth 1M, the land na tinayuan mo is worth 5M, pwede, you can be compelled to

buy the land. Bad faith ka, pasaway ka, kasalanan mo, and you are liable for damages. The land owner

would have the right to demand removal. “Tanggalin mo yan, lumayas ka sa lupa ko”. Basta in bad faith, you

have no rights whatsoever EXCEPT isa lang: yung recovery of necessary expenses for the preservation of

the property. Why so? Kasi pag dating sa necessary expenses, since these are supposedly incurred for the

preservation of the property, the land owner himself would have incurred the same expenses. Even if he

was the one who has possession of the property. So, in terms of fairness and basic justice, the law

mandates that the builder in bad faith should be entitled to this. By the way, all fruits of the property

belong to the owner. Siguraduhin lang natin na talagang fruits. There is an old case – the “Bonus”. Certain

land owners were asked by a certain company “pwede ba i-mortagage ninyo yang mga lupa ninyo para maka

secure kame ng loan? For the risk you are going to take, we will give you certain bonuses.” Pumayag,

minortgage, so binigyan ng bonuses. Are these bonuses fruits? The answer is NO because they were not

produced by the land, not even civil fruits.

Transcribed By: Bjone Favorito Page 14

Supposing that both the land owner and the builder are in bad faith? Then they are both

considered to have acted in good faith. So you apply the provision of Art.448. Supposing that the builder

used the materials of a third person in building on the land of another, it would depend on whether the

builder and the land owner are in good faith or in bad faith. Assuming that they are both in good faith,

and the material owner is also in good faith, what will be the rights of the owner of the materials? He can

recover the value of his materials from the builder who used it but the land owner can be held subsidiary

liable for the value of the materials in case the builder is unable to pay the owner of the materials their

value. If, however, the builder is in bad faith, and consequently, the land owner demands the removal or

the demolition of the building, remember that the land owner will have no subsidiary liability. Why? In

Accession, he who benefits from the accession must pay for it. That’s one underlying principle. Kung sino

nakinabang sa accession, dapat mag bayad. That’s the reason why if the land owner decides to appropriate

the building, there is subsidiary liability on his part in case the builder is insolvent. If the land owner

decides to ask for the removal, he does not benefit from that accession and, therefore, there would be no

subsidiary liability on his part. Which is also the reason why if the property is sold by the land owner

pending payment of the indemnity to the builder, who will pay the indemnity to the builder? It depends,

if in the contract of sale between the land owner and the third person, if the land owner was already paid

not just the value of the land but the value of the building as well, then the land owner must pay the

value of the building (proper indemnity) to the builder. If on the other hand, the land owner was not paid

the value of the building, then he does not benefit from the building, it would then be the buyer who will

benefit from the accession, it will be the buyer who will have to pay the builder the proper indemnity. I

repeat, he who benefits from an accession must be the one to pay for it.

Alluvion

Art.457 – if you are the owner of a parcel of land adjoining the bank of a river, and due to the

natural action of the water over a period of time, deposits of river sill are left there by the water, such that

the area of your land gradually increased year after year, you are the owner of that additional area. Your

ownership is automatic. The additional area brought about by the alluvion automatically belongs to the

land owner of that land adjoining the banks of a river. It (the additional area) is not, however,

automatically registered or covered or protected by the torens title of the land owner. He has to register it

in his name and, if prior to his registration of the additional area, a third person succeeds in occupying

that area, claiming it as his own, satisfies the requisite for acquisitive prescription, that third person

would have acquired ownership over that area. So I repeat, if you are the owner of a property adjoining

the banks of a river, in the course of many years, due to the gradual deposit of river sill, lumaki ng lumaki

yung area mo, automatically, as long as everything happens naturally, hindi ka nag construct ng catchment

basin or whatever there, no human intervention, you are the owner of the additional area through

alluvion. But that area is not automatically covered by your torens title. The torens title will not

automatically extend to the additional area. Therefore, the additional area can still be acquired by third

persons through acquisitive prescription. The increase in the area must be exclusively due to nature.

There must be absolutely no human intervention, otherwise that is not alluvion.

Transcribed By: Bjone Favorito Page 15

In so far as areas bordering lakes are concerned, like Laguna de Bay, if there are additional areas brought

about by the action of the water or whatever, to whom would these areas belong? They would belong to

the owners of the adjacent lands applying the Spanish law on waters. If you own a parcel of land, let’s say

in La Union, and through the action of the sea, your land gradually increased in area, who would own

the additional area? Kabalikat sa Kaunlaran, wag natin pakialaman yan, that belongs to the State. Alluvion is

applicable only in rivers, hindi kasama dito yung mga shores of the seas but, applying the Spanish law on

waters, if what is involved is a lake, the additional area will also belong to the adjacent land.

Transcribed By: Bjone Favorito Page 16

USUFRUCT

Nothing complicated about Usufructs. The basic idea of Usufruct is: Property is given to a

person, is given the right to use and enjoy the property, with the basic obligation of preserving its form

and substance. Basically, that’s what usufruct is all about. You try to remember at least a few of the

distinctions between a usufruct and lease. You need not remember all of the distinctions, just some of it.

For example, is that usufruct is always a real right. In the case of lease, it’s not always a real right. It

becomes a real right only if the period is more than 1 year, or if it is registered. A usufruct can only be

created by a person who owns the property. Sya lang ang pwede mag constitute ng usufruct. Yung lease

pwede, it can be created by somebody who is not actually the owner of the property. For example, the

lease may sub-lease the property. In the matter of its creation, there are various ways of creating a

usufruct. It may be created by the law itself or by the will of the testator. In the case of a lease, generally

the only possible source of the lease is the contract between the parties, except of course in the case of the

implied new lease. Or in the case of the forced leased under Art.448 – “if the value of the land is

considerably more, etc.” – just remember those cases.

Rights of the Usufructuary

You remember the rights of a usufructuary. So if you are the usufructuary, what will be your

rights? Basically, you can use the property, you’re entitled to all of the fruits – whether natural, industrial

or civil fruits. Supposing there are hidden treasures, the usufructuary, the law says, is considered a

stranger. In other words, if somebody finds the hidden treasure, then the usufructuary does not get any

share. If it is the usufructuary himself who finds the treasure, then he may be entitled to one half and the

other half will go to the naked owner of the property.

You remember the provisions of the law regarding growing or pending fruits. Those fruits which

are growing or pending at the commencement of the usufruct will belong to the usufructuary. Those

growing or pending fruits, at the time of the end or termination of the usufruct will belong to the naked

owner. With respect to the fruits pending at the time of the start, sabi naten they would belong to the

usufructuary – does he have to refund to the naked owner the expenses incurred so far? There is no need

to refund. But when it comes to the fruits pending at the time of termination of the usufruct, while the

law says that they belong to the naked owner, the naked owner has to reimburse the usufructuary the

expenses incurred by the latter for cultivation, seeds and other similar expenses. If the property under

usufruct is tenantable, you can lease or rent it out to tenants, and it is the usufructuary, not the naked

owner, who has the right to determine who will be the tenant of the property.

If there are any accessions, for example the property under usufruct happens to be a piece of land

located along the banks of a river, and in the course of time, the area increased because of alluvion, the

usufructuary has the right to make use of the additional area. That’s part of his right under Art.571. the

usufructuary may decide to personally use the thing, enjoy it or he may allow another person to enjoy the

thing under usufruct. But remember that all contracts entered into by the usufructuary with third persons

are co-terminus with the usufruct, with the exception of lease of rural lands, which shall be deemed to

Transcribed By: Bjone Favorito Page 17

continue up to the end of the agricultural year. The obvious purpose there is to allow the lessee who may

be cultivating the land to continue with the production and gathering.

Usufruct imposes upon the usufructuary the obligation of preserving the form and substance of

the thing. But the law allows the grant of a usufruct over the entire patrimony of a person, and when that

happens, chances are, in that patrimony, there will be some properties which, by their very nature, will

deteriorate or will be impaired do to ordinary wear and tear. Supposing that what has been given by way

of usufruct is property which gradually deteriorates through ordinary use, ordinary wear and tear. For

example the object is a car – if the usufruct is for five years, after the period iba na yung kotseng yan.

Ordinary use of the car will result in ordinary wear and tear. Can the usufructuary use the property? The

answer is yes, pwede parin. What will be his obligation? He is simply obligated to return the thing in the

condition in which it may be at the time of termination of the usufruct. If the thing suffers damage or

injury due to his fraud or negligence, he is obligated to indemnify. Pero kung ordinary wear and tear lang

– no obligation. He simply has to return the thing in the condition in which it may be found at the

termination of the usufruct.

Can there be a usufruct on consumable things? Those which cannot be used in a manner

appropriate to their nature without their being consumed or used-up. Can there be a usufruct on money?

On rice? The answer is YES. These are what are sometimes called “abnormal usufructs on consumables”,

sometimes called “quasi-usufructs”, but I think the better view, as pointed out by some commentators, is

: if the object of a usufruct is consumable, in effect, what you have is a “simple loan”. So what will be the

obligation of the usufructuary? Syempre he uses, he consumes. Then he simply has to return or pay the

appraised value at the time of termination of the usufruct, if it was appraised. If it was not appraised, he

will have the obligation of returning the same quantity and quality or pay their “current value”. That is

one advantage of having an appraisal – at least, you only have to return the appraised value.

With respect to usufructs on fruits-bearing trees, remember, the usufruct cannot cut down the

trees but he is allowed to use the trees which have been up-rooted by accident – the dead trunks, he can

use them but if he does, he has the obligation to replace them with new plants. Halimbawa santol or manga

or caimito or star apple. If there is something extra ordinary which happens, and the trees have been up-

rooted or disappeared in such extra ordinary number that it would be impossible or too burdensome to

replace them, the usufructuary may simply demand from the naked owner to clear the land so that he can

continue using the land, or, if he wants, he can use them (the trees), but if he does, he will have the

obligation to replace them with new trees pursuant to Art.575.

Usufruct over wood land: the usufructuary is allowed to make such ordinary felling and cutting

as the owner was in the habit of doing or in accordance with the customs of the place. You remember, in

this connection, ang coconut land is not wood land. Hindi pwedeng mag putol ng puno ng nyog ang

usufructuary.

Supposing the usufructuary introduces useful improvements, or improvements for mere

pleasure or ornamental improvements on the property under usufruct, can he do it? YES, as long as he

does not alter the form and substance of the thing under usufruct. Can he demand reimbursement for the

Transcribed By: Bjone Favorito Page 18

expenses he incurred? The answer is NO. He cannot claim reimbursement for useful or ornamental

expenses, but he can set off (offset) the value of these improvements against any possible liability for

damages which he may have incurred.

Obligations of the Usufructuary

What are the obligations of a usufructuary? At the start of the usufruct, there are two basic

obligations. Number one: he must submit an inventory of the things under usufruct. Number two: he

must also give a sufficient security. What will be the security for? To guarantee his compliance with his

obligations as a usufructuary. When is an inventory not required? When no one will be injured, provided

that the naked owner consents to the non-submission of the inventory in case the naked owner waives

the requirement for an inventory or if there is such a provision in a will, where the usufruct was created,

or in the contract creating the usufruct. What about the security? When is a security not required? Again,

when no one will be injured, provided that the naked owner consents, second, if there is waiver on the

part of the naked owner, third, if the usufructuary happens to be the donor of the thing – sa kanya

nanggaling, binigay nya but he reserves the usufruct of the property, he is not required to furnish a

security. In the case of caucion juratoria – the promise under oath, the usufructuary is also not required to

furnish a security.

What will be the legal consequence if there is a failure to provide the security? We have the

provisions of Art.586. In that case, the naked owner may demand that the movables be placed under

administration, that the movables be sold, that the public bonds or instruments of credit be converted

into registered securities or certificates, and that the cash and the proceeds of the sale of the movables be

invested in safe securities. The usufucrutuary will be entitled to the interest on these sales of the

movables, and the other proceeds of the properties placed under administration.

What is the Caucion Juratoria? Sometimes it may happen that the usufructuary is given the

usufruct of certain properties, for example house or furniture, equipment or tools, but he does not have

money to get the necessary security. In that case, he may petition the court to allow him to make use of

the house so that he and his family can live there, that he be allowed to use the furniture, equipment and

implements of a trade so that he can earn money. That may be granted by the court upon the promise of

the usufructuary under oath. Kaya ang tawag dyan “caucion juratoria” – that he will take care of it as

required by law.

A usufructuary is obliged to take care of the thing with the diligence of a good father of a family.

Supposing he fails in that obligation, he abuses that thing, or he misuses the thing, will that cause the

termination of the usufruct? The answer is NO. What is the remedy? The owner may simply ask that

administration be given to him pursuant to the provision of Art.610. if the usufruct is constituted on a

herd of livestock, the law says he is obligated to replace with the number of those which are lost each

year due to natural causes or due to the rapacity of beasts of prey. Yung mga nawawala dahil sa mga

mandarambong – beasts of prey, mga hayop na mababagsik.

Supposing that the usufruct is constituted on sterile animals, yung mga hayop na baog, hindi

pwedeng manganak, what will be the obligation of the usufructuary? It will be considered as if the usufruct

Transcribed By: Bjone Favorito Page 19

was constituted on fungibles. In other words, the usufructury simply has the obligation to pay their

appraised value if appraised or, if not, to replace them with the same quantity and quality or pay their

current value at the time of the termination of the usufruct. A good example of a sterile animal would be

a mule, the one usually used to carry things or cargo, yung mga panahon ng cowboys at indian. It is a

sterile animal, and you produce a mule by cross-breeding a male donkey with a female horse, the

offspring will be a mule.

Who is responsible for repairs? You distinguish between ordinary and extra ordinary repairs.

Ordinary repairs are the responsibility of the usufructuary. When is a repair considered ordinary? If it is

due to wear and tear, and if it is indispensable to the preservation of the thing. So two requisites. The

usufructuary is obliged to make the ordinary repairs. All other repairs are considered extra ordinary.

Halimbawa, due to wear and tear, but not indispensable to the preservation of the thing, that’s

considered extra ordinary. Such repairs shall be, according to the law, at the expense of the naked owner.

But the naked owner, please take note, is not obliged to make the extra ordinary repairs.

Supposing the naked owner makes the extra ordinary repairs, he spends for it, what right would

he have? Under the law, he would have the right to demand from the usufructuary legal interest on the

amount he spent on the extra ordinary repairs for the duration of the usufruct. Supposing the repair is

extra ordinary and indispensable for operation but not caused by ordinary wear and tear, for example the

property under usufruct is a house, may malakas na bagyo at linipad ang bubungan – that’s not due to

ordinary wear and tear but it is indispensable to the operation of the property. And let’s further assume

that the naked owner does not make that extra ordinary repair. In that case, since it is indispensable to the

preservation of the things, the usufructuary may make that extra ordinary repair. What would be his

rights? He may demand from the naked owner, at the termination of the usufruct, the increase in value

which the thing may have acquired as a consequence of the repair.

Annual charges and taxes which are considered lien on the fruits – charged to the usufructuary.

Real property tax on the land under usufruct – that should be paid by the naked owner, not by the

usufructuary.

If the usufruct is constituted on the whole patrimony of the person, and the naked owner

happens to have unpaid debts, is there an obligation on the part of the usufructuary to pay the debts? If

there is no order for the naked owner to pay the debts, there is no obligation on the part of the

usufructuary to pay those debts except if the usufruct was constituted in fraud of creditors. If there is an

order from the naked owner for the usufructuary to pay the naked owner’s debts, it is understood that he

is obligated to pay only to pay the debts existing at the time the usufruct was constituted. Only pre-

existing debts must be paid, applying the provisions of Art.758 and 759.

Transcribed By: Bjone Favorito Page 20

Extinguishment of Usufruct

How is usufruct Extinguished? You take note of the provisions of Art.603.

The death of the usufructuary generally terminates the usufruct. What about the death of the

naked owner? It does not terminate the usufruct.

Merger would also result in termination of the usufruct, meaning to say, if there is merger of both

the usufruct and the ownership of the same property in the same person, then the usufruct is necessarily

terminated.

Total loss of the thing – that also results in the termination of the usufruct.

Termination of the right of the person constituting the usufruct – that also terminates the

usufruct. If I gave you the usufruct over a parcel of land, and during the existence of the usufruct, my

rights are declared, by final judgement of a court, to be null and void – I’m not really the owner, that’s an

example of a situation where the usufruct will be terminated by the termination of the rights of a person

constituting the usufruct.

Renunciation on the part of the usufructuary – that would also terminate the usufruct. Does a

renunciation require the consent of the naked owner? The better view is that it does not. If the loss is not

total, but partial, needless to state, the usufruct continues on the part of the thing which has not been lost.

In the case of multiple usufructs, it is only upon the death of the last usufructuary that the

usufruct is terminated. Supposing that the usufruct is granted for the number of years that would elapse

before a person would reach a certain age. Let’s say I give you a usufruct today until X reaches the age of

40, and X is, let’s say, only 30 years old today. So, the usufruct is supposed to last for 10 years. Supposing

X dies after 5 years, will the usufruct terminate? The answer is NO. It continues until the year when he is

supposed to reach 40. Unless the usufruct was granted only in consideration of the existence of X, in

which case, it would terminate upon the death of X.

You take note of the provisions of Art.607. Two situations contemplated here.

First: usufruct is constituted on both the land and the building, and then the building is

destroyed. What is the consequence? The usufruct over the land continues. Usufructuary has the right to

continue using the land and he has the right to make use of the materials. If the naked owner wants to

rebuild, his decision is subject to the concurrence or consent of the usufructuary because his usufruct is

over both land and the building. If the usufruct is constituted over the building only, not expressly

covering the land, and the building is destroyed, the usufruct on the building ends but the usufructuary

can still make use of the materials. The usufructuary in that situation is also entitled to the continuous use

of the land because, although the land was not expressly included in the usufruct, of course, the building

cannot be floating on thin air, so when he was granted usufruct of the land, necessarily, kasama din yung

pinagkaka tayuan nun. It necessarily included his right to make use of the land on which the building

stands. If the naked owner rebuilds, he has the obligation to pay the usufructuary interest not only of the

value of the materials, but also on the value of the land. Bakit may interest pati sa value of the land?

Transcribed By: Bjone Favorito Page 21

Because, sabi nga natin, even if the usufruct expressly covered only the building, it necessarily included

the use of the land because a building cannot float. If the property under usufruct has been expropriated,

what will be the consequence? The naked owner has the obligation to either replace it with another

property of the same kind and value or, depending on the naked owner, he can simply pay the

usufructuary interest on the indemnity paid to him. This was precisely the rule applied by the SC in the

case of Locsin vs. Valenzuela, where the property under usufruct was taken under P.D.27 – yung “given to

the tenant”.

Transcribed By: Bjone Favorito Page 22

EASMENTS

A few important points to remember: try to take note of some of the distinctions between

easement and lease. One distinction is that an easement is a real right, lease is a real right only when more

than one year and registered. Another important distinction is that you can only have an easement with

respect to immovable property or real property, yung lease pwede kahit na personal or movable property.

Kinds of Easments

Remember the various types or classifications of easements. An easement may be continuous or

discontinuous, apparent or non-apparent, positive or negative. When is an easement considered

continuous? If its use does not depend upon the acts of men. It is discontinuous if its use depends upon

the acts of men. If it’s only used at intervals, and depends upon the acts of men. When is an easement

apparent? If there is an external sign which continually keeps it in view and reveals its use and

enjoyment. It is non-apparent if there is no visible indication of its existence. When is an easement

positive? When it imposes upon the owner of the servient estate the obligation of allowing something to

be done or of doing it himself. It is negative if it prohibits and prevents the owner of the servient estate

from doing something which otherwise he could lawfully do where it not for the existence of the

easement.

Continuous easement – an easement of drainage, of abutment of a dam, of light and view – these

are continuous easements. The easement of light and view continues to be in use even if there is nobody

making use of the light and view. Discontinuous easement – right of way, because it’s impossible for a

man to be continuously walking to and fro through the right of way, 24 hours-a-day, 7 days-a-week. Its

use depends upon human intervention, upon the right of man.

What about an apparent easement? If the right of way is permanent, there is a permanent road

there, that’s apparent. Again, abutment of a dam, kitang kita mo, nandyan yan. An easement of aqueduct,

by express legal provision, is always considered continuous and apparent. Therefore, it can be acquired

by prescription. Non-apparent easement – the easement of Altius non tollendi, where you are not

supposed to build beyond a certain height. If you are the servient owner and there are people passing by

your property, there is nothing which will indicate that the reason why you are not building beyond a

certain height is because there is an easement. So it is non-apparent.

The easement is positive if it imposes upon the owner of the servient estate the obligation of

allowing something to be done or of doing it himself. A very good example would be an opening made

on a party wall – an easement of light and view through a party wall – that’s a positive easement because

it imposes upon the owner of the servient estate the obligation of allowing something to be done on the

servient estate itself. Negative easement – the easement of light and view is negative if you make the

opening on your own wall. So as to the wall facing the property of another you make an opening – that,

as long as you comply with the requirements of a notarial prohibition, will be a negative easement. Why?

Because the owner of the servient estate will be prohibited from doing something which lawfully he

could do where it not for the existence of the easement. And that is: to block your light and view.

Transcribed By: Bjone Favorito Page 23

Modes of Acquiring Easments

Remember that an easement is inseparable from the estate to which it either actively or passively

belongs. You cannot alienate an easement separately from an estate to which it belongs. How are

easements acquired? Either by title or prescription, but remember one very important rule: only