Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Evidence-Based Practices and Students With Autism Spectrum Disorders

Uploaded by

Marta Balula DiasOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Evidence-Based Practices and Students With Autism Spectrum Disorders

Uploaded by

Marta Balula DiasCopyright:

Available Formats

Evidence-Based Practices and

Students With Autism Spectrum

Disorders

Richard L. Simpson

The past several years have been witness to a variety of educa- perception that improved student outcomes will be most likely

tion reform and reorganization efforts, including for students to occur within a restructured education system (Egnor, 2003;

with disabilities. Prominent among these restructuring efforts Robelen, 2002).

have been initiatives that require educators to adopt practices Education restructuring includes teachers’ willingness and

that are supported by research. Noteworthy examples of this ability to adopt and properly use effective-practice materials

trend include the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 and other

and strategies (Lerman, Vorndran, & Addison, 2004). Indeed,

calls for use of effective practice methods by educators and

a salient element of NCLB relates to using effective education

others who are connected with students with disabilities. Al-

though this is a daunting challenge for any group of students, practices developed from scientifically based research (SBR).

the process of identifying and consistently and correctly using Such practices are defined as those that have met rigorous peer

effective practice methods has been especially demanding for review and other standards and that, when consistently and re-

professionals who work with children and youth with autism liably applied with fidelity, have a history of yielding positive

spectrum disorders. This article discusses issues and factors that results (Simpson, LaCava, & Graner, 2004).

relate to identifying and using effective practices with students The call for effective and scientifically supported methods

with autism-related disorders. Recommended effective practice for use with students with disabilities extends beyond NCLB

methods are also provided. and other legislative and policy statements (Odom et al.,

2005). This appeal has been particularly trumpeted within the

field of autism spectrum disorders (ASD; National Research

S

igned into law in January 2002, the No Child Left Be- Council, 2001). Demands and pleas for adoption of effective

hind Act of 2001 (NCLB) is an ambitious congressional practices for children and youth with autism and related dis-

attempt “to ensure that all children have a fair, equal, and abilities are connected, at least in part, to the significantly in-

significant opportunity to obtain a high-quality education, and creased prevalence of ASD (American Psychiatric Association,

reach, at a minimum, proficiency on challenging state aca- 2000) and a longstanding tradition and legacy of accepting,

demic achievement standards and state academic assessments” condoning, and even promoting methods and strategies that

(NCLB, 2002). Included in the noteworthy, standards-based lack efficacy and proven utility (Gresham, Beebe-Frankenberger,

NCLB enactment is the expectation that all students, includ- & MacMillan, 1999; Simpson, 2004). This article addresses

ing those with disabilities, will demonstrate annual yearly several issues connected to identifying and using scientifically

progress (AYP) and perform at a “proficient” level on state supported and effective-practice methods with students with

academic assessment tests. The means, suitability, and even the ASD. Effective practices for students with ASD are identified.

sensibility for accomplishing these lofty goals are under intense

debate (Albrecht & Joles, 2003; Allbritten, Mainzer, & Zieg-

ler, 2004; Center on Educational Policy, 2003). Algozzine Controversial Interventions and

(2003), for example, observed that federal control is being ex- Treatments for Students

erted through discretionary and other incentives to state and With ASD

local education agencies, even though the U.S. federal gov-

ernment has no designated power to manage education. Yet, Notwithstanding noteworthy advancements in treating and

independent of these debates, there is general agreement that understanding individuals with ASD, autism-related disabili-

improving students’ performance and outcomes is an impor- ties remain largely inexplicable (Frith, 2003). Thus, in spite of

tant and necessary endeavor. Moreover, increasingly there is a crucial and meaningful gains in information about ASD and

FOCUS ON AUTISM AND OTHER DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES

VOLUME 20, NUMBER 3, FALL 2005

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at LAKEHEAD UNIV on March 13, 2015

PAGES 140–149

VOLUME 20, NUMBER 3, FALL 2005

141

procedures and intervention strategies that benefit individuals for which there is neither a clear explanation nor a universally

with ASD, persons with autism-related disorders remain an accepted course of treatment. When confronted with oppor-

enigmatic group. Highly unique and idiosyncratic character- tunities and options that purport to lead to significantly im-

istics associated with ASD, manifestation of irregular and oc- proved outcomes, even if the techniques that are being

casionally even advanced skills that accompany diagnoses of considered lack scientific validation, it is understandable that

autism, and a remarkably increased prevalence of ASD (Amer- many parents, as well as numerous professionals who work

ican Psychiatric Association, 2000; Autism Society of America, with these children and youth, are willing to consider and even

2005) are only a few of the factors that have fueled significant forcefully advocate for approaches that promise improved out-

debate about which treatment and intervention choices are comes or to restore an individual to normal functioning. Kalb

most apt to lead to favorable outcomes (Prizant & Rubin, (2005) poignantly makes this point in a Newsweek feature ar-

1999). ticle on autism, commenting on one family’s search for treat-

Furthermore, related to its perceived distinctiveness and ments: “Since their sons were diagnosed [with autism], both

inimitability and because autism is considered to be a life-long, at age 2, Barry and Dana Craven have tried a dizzying array of

permanent disability, autism-related disabilities have attracted therapies: neurofeedback, music therapy, swimming with dol-

a number of highly controversial treatments and intervention phins, social-skills therapy, gluten-free diets, vitamins, anti-

strategies (Bettelheim, 1967; Biklen & Schubert, 1991; Sill- anxiety pills and steroids” (p. 45).

man, 1995). In this context, controversial is a reference to un- In spite of the comprehensible reasons for the current in-

validated methods and strategies for which there is little in the tervention and treatment dilemma, it is nonetheless painfully

way of scientific support and efficacy, especially when extraor- evident that unrestricted use of and reliance on untested meth-

dinary and incomparable results are promised (Simpson & ods, especially those that promise extraordinary results, have

Myles, 1998). been detrimental to the ASD field. Gullible and uncritical ac-

ceptance of interventions and treatments that promise phe-

nomenal results and acceptance of unvalidated methods and

Effective and Scientifically Valid strategies that capriciously and naively supplant proven strate-

Interventions and Treatments gies have undermined wide-reaching identification, correct

for Students With ASD implementation, and prudent evaluation of methods that bode

best for children and that may be the prerequisite foundation

Persons associated with children and youth with autism and for effective programs for students with ASD. In short, de-

autism-related disorders are not exclusive in their struggle to pendence on and uncritical use of miracle cures and unproven

sort between effective and ineffective interventions and treat- methods have encouraged unhealthy, unrealistic, and improb-

ments and to identify the salient components of an effective able expectations and have, in all too many cases, retarded the

program. Indeed, no area of disability has managed to escape progress of students with ASD.

the difficulties associated with controversial and unsupported The apparent solution to this dilemma is to identify and

treatments and interventions (American Speech-Language- use scientific methods and evidence-based practices (Shavelson

Hearing Association, 2004). Yet, no area of disability has ex- & Towne, 2002). This clear-cut and evident answer is appeal-

perienced this problem to the same degree as those within the ing and has obvious value. Yet its implementation is fraught

autism field. Parents and professionals connected to children with Herculean challenges. Regarding using a science-oriented

and youth with ASD have been singularly and exceptionally strategy for identifying and adopting evidence-based methods,

prominent in their willingness to consider and advocate use of Odom and his colleagues sagely observed that “the ‘devil is in

unproven and controversial interventions and treatments, in- the details’” (Odom et al., 2005, p. 137). To be sure, there

cluding strategies and methodologies that supposedly lead to are significant difficulties and a lack of consensus regarding

attainment of skills, knowledge, and progress that are well be- how best to identify, use and evaluate scientifically valid and

yond those characteristically found with established effective- effective practices (U.S. Department of Education, 2003).

practice methods (Heflin & Simpson, 2002; Volkmar, Cook, NCLB has prominently and aggressively supported the use

& Pomeroy, 1999a). That some of these methods are pro- of SBR in selecting educational practices. Mentioned more

moted to result in rapid, all encompassing, and dramatic im- than 100 times in NCLB, SBR is defined as “research that in-

provements, or to actually restore an individual with an volves the application of rigorous, systematic, and objective

autism-related disability to normalcy, has been particularly procedures to obtain reliable and valid knowledge relevant to

problematic. education activities and programs” (NCLB, 2002). Accord-

The appeal and lure of overvalued and unvalidated inter- ingly, NCLB has identified effective SBR practices as those that

ventions and treatments are both explicable and arguably even have met thorough and particular standards and that have re-

logical. Consider and identify with the parents of children with liably yielded positive results when applied in the approved

autism: These individuals are confronted with raising children manner. Rigorous peer review policies and strategies are the

who have been identified with a life-long pernicious disability preferred means for testing and confirming that practices are

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at LAKEHEAD UNIV on March 13, 2015

FOCUS ON AUTISM AND OTHER DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES

142

scientifically based. More specifically, scientifically based prac- The WWC strategy for identifying SBR practices is the De-

tices include products and materials validated by means of re- sign and Implementation Assessment Device instrument and a

search designs that use random samples and control and related protocol for ensuring that methods are scientifically

experimental groups. This model of research is considered by verified (What Works Clearinghouse, 2004). The Design and

NCLB to be the “gold standard.” For a variety of sound rea- Implementation Assessment Device and its related validation

sons, however, randomized control group designs are infre- process are particularly controversial due to the requirement

quently used in research involving children and youth with that evidence-based and SBR practices should be supported by

autism-related disorders. This narrow interpretation of what is randomized experimental group design methodology (White

scientifically valid has broad and significant implications re- & Smith, 2002). Such research methodology has typically not

lated to endorsing intervention and treatment practices for been used to evaluate ASD methods, primarily because of lim-

children and youth with ASD. ited samples of students with ASD with similar characteristics,

Smith (2003) attempted to explain NCLB’s narrow inter- programs, needs, and so forth. Moreover, it appears obvious

pretation of SBR by citing the U.S. Department of Educa- that different research methodologies are needed to answer

tion’s Questions and Answers on No Child Left Behind: Doing different questions (Horner et al., 2005; Shavelson & Towne,

What Works, a guidance tool for parents and educators: 2002). For example, identifying effective management inter-

ventions for highly idiosyncratic self-injurious behaviors of

To say that an instructional program or practice is grounded in youth with severe forms of autism might best be undertaken

scientifically based research means there is reliable evidence that using a single-subject design validation approach. Similarly, a

the program or practice works. For example, to obtain reliable ev- possible environmental or educational link associated with cer-

idence about a reading strategy or instructional practice, an ex-

tain outcomes might best be identified using correlational

perimental study may be done that involves using an experimental/

methods (Thompson, Diamond, McWilliam, Snyder, & Sny-

control group design to see if the method is effective in teaching

children to read. der, 2005). Accordingly, using a variety of methodologies to

identify effective practices for students with ASD appears to be

[NCLB] sets forth rigorous requirements to ensure that research the most sensible and pragmatic path for the ASD field to fol-

is scientifically based. It moves the testing of education practice

low. At the same time, even though there is controversy re-

toward the medical model used by scientists to assess the effec-

garding the precise means of determining scientific evidence,

tiveness of medications, therapies and the like. Studies that test

random samples of the population and that involve a control there is an obvious need for professionals and parents to be

group are scientifically controlled. To gain scientifically based re- able to identify effective methods for students with ASD

search about a particular educational program or practice, it must (Browder & Cooper-Duffy, 2003; National Research Coun-

be the subject of such a study. (p. 126) cil, 2001; Volkmar, Cook, & Pomeroy, 1999b).

In summary, the SBR requirement of NCLB appears to re-

The call for implementation of scientifically based practices strict and impede identification of effective practices for stu-

was strongly promoted by the Coalition for Evidence-Based dents with ASD. Research involving students with ASD often

Policy (Council for Excellence in Government, 2002). On the precludes use of randomized group design methodology be-

basis of the argument that decades of stagnation in American cause of limited student samples, heterogeneous clinical edu-

education needed to be reversed through the promotion of cational programs, and the need for flexibility in matching

evidence-based practices, the Coalition proposed, in 2002, research designs to specific questions and issues under investi-

that the U.S. Department of Education establish a knowledge gation. The National Research Council (2001) recognized that

base of validated educational interventions that have been there are important occasions when randomization is not fea-

proven effective in clinical trials using large-scale replication sible. Furthermore, Sailor and Stowe (2003) correctly observed

methods and create incentives for programs that receive fed- that “No Child Left Behind and accompanying education leg-

eral education funds to use such interventions. islation at the federal level . . . has begun to not only inform

In August 2002, to facilitate the aforementioned valida- inquiry, but also to restrict it” (p. 151). Algozzine (2003) fur-

tion process, the U.S. Department of Education awarded thered this line of reasoning by observing that government

$18.5 million to the What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) to control of discretionary funds and other incentives allows the

assess and report on effective programs (Eisenhart & Towne, government to wield power over state and local education

2003). Designed to be “a central, independent and trusted agencies, institutes of higher education, and any other indi-

source of evidence about what actually works in education,” viduals who must comply with NCLB, thus effectively imped-

the WWC was intended to provide information about reliable, ing the very goal that NCLB pursues: the identification of

scientifically based practices and supporting evidence from scientifically valid methods for all students, including those

which educators could make choices. Because the WWC has with ASD. Finally, Eisenhart and Towne (2003) prudently

posted few results of their investigation of products or prac- called for more dialogue among individuals involved in the

tices, it is unclear whether they will be successful in this effort. NCLB SBR debate, perceptively noting that “more of it” is an

This is particularly the case with students identified with ASD. obvious need (p. 35).

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at LAKEHEAD UNIV on March 13, 2015

VOLUME 20, NUMBER 3, FALL 2005

143

It is evident that identification of effective practices for stu- catalogs, and in the brochures of companies that sell educa-

dents with ASD extends far beyond NCLB. Indeed, profes- tional and psychological materials, which is clear testament to

sionals and family members must ultimately determine whether this problem. Just because a brochure indicates that a partic-

a particular strategy or method that is deemed to be an effec- ular method is supported by research does not make it so.

tive or scientifically based method is suitable for an individual Practitioners and others who recommend a particular material

student. Accordingly, the onus for making responsible meth- or method must have an understanding of its utility and un-

odology decisions falls with teams of professionals and parents. derlying scientific support.

Professionals and parents require access to straightforward in- Determining whether a method is objectively verifiable is

formation about the efficacy of various methods, as well as sup- essential. Thus, as outlined in NCLB, interventions and treat-

plementary information that will assist them in determining a ments for students with ASD must demonstrate their worth.

method’s suitability with individual students. Moreover, it is They must pass rigorous and objectively measured standards

essential that the professionals and parents who are making de- and demonstrate value by producing positive outcomes when

cisions about which methods to use demonstrate a willingness used correctly. It, however, is also strongly recommended that

and ability to use this information in a collegial and collabora- the autism community recognize that objectively verifiable is

tive fashion. There appears to be little doubt that the success- not limited to a single form of supporting research and effi-

ful identification and implementation of effective practices will cacy. That is, “rigorous, systematic, and objective procedures”

best be made at the local level by groups of professionals and that recognize “reliable and valid” (NCLB, 2002) interven-

parents who possess the most knowledge and information tions and treatments can take multiple forms (e.g., single-

about individual students. Teachers, other professionals, and subject designs, correlation studies, quasi-experimental designs),

parents involved in the decision-making process must become in addition to research designs that have random samples and

better consumers of objectively verified and effective inter- control and experimental groups. The salient issue in judging

vention methods available for use with children and youth with the merits of a particular method is whether there is objectively

ASD. verifiable supporting evidence that is appropriate for the issue,

circumstances, and conditions that are under investigation.

Objectively verifiable supporting information and data in the

Recommendations for Professionals form of high-quality studies in peer-reviewed journals are un-

and Parents questionably vital and necessary. Although non–peer-reviewed

materials on Web pages and other briefly written, easily read,

Based on work of Heflin and Simpson (1998), we propose the and effortlessly accessed and convenient information has clear

following recommendations for helping professionals and par- appeal, these sources of support often lack the credibility, ob-

ents become better consumers of intervention methods for jectivity, and impartiality of more traditional forms of research

students with ASD and for deciding the suitability of various information. Information from a single source that is not sup-

intervention options. Three basic questions can be used to fa- ported by other researchers and entities and information that

cilitate selecting a program or method for individual students lacks peer review and empirical validation but instead comes

diagnosed with ASD: primarily from personal testimonials should be considered

1. What are the efficacy and anticipated outcomes that with caution. Furthermore, many objective and peer-reviewed

align with a particular practice, and are the anticipated out- research reports are available via Internet sites (see, for exam-

comes in harmony with the needs of the student? ple, Pyramid Educational Consultants, 2005).

2. What are the potential risks associated with the practice? In addition to an evaluation of the overall effectiveness and

3. What are the most effective means of evaluating a par- usefulness of a method, the assessment process must include

ticular method or approach? an appraisal of the extent to which the outcomes associated

with an approach align with the needs of an individual student.

Furthermore, it is recommended that product or procedure

Question 1

consumers consider the extent to which supporting research

The first question asks, What are the efficacy and anticipated was conducted with students who are similar to the student

outcomes that align with a particular practice, and are the an- for whom the product is being considered. A severely impaired

ticipated outcomes in harmony with the needs of the student? child with limited language, for instance, may be a poor can-

This process involves assessing the merits of a particular ap- didate for a scientifically supported method that primarily fo-

proach, including what the approach purports or has been cuses on pragmatic social language outcomes and that was

found to accomplish with persons with ASD or similar condi- validated using high-functioning students with intact expres-

tions. This is not a straightforward and undemanding process, sive verbal communication skills.

at least in part because of the slapdash and ubiquitous use of Assessment of the suitability of a method should also in-

such terms as evidence-based, research-based, and so forth. clude an evaluation of its potential social validity (Maag, 2004;

These terms are prominently displayed on the Web sites, in the Wolf, 1978). Given the multiple and pervasive challenges fac-

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at LAKEHEAD UNIV on March 13, 2015

FOCUS ON AUTISM AND OTHER DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES

144

ing children and youth with ASD, it is essential that maximally Question 3

significant targets be addressed and that these targets have piv-

otal importance. Because individuals connected to students The third question addresses how a method or strategy will be

with ASD may have differences of opinion, it is recommended evaluated. This involves considering the process and proce-

that this process be undertaken by multiple individuals who dures that may be used to determine whether a particular

have varied perspectives, including parents and family mem- method is able to produce desired and anticipated outcomes.

bers, students, teachers, and so forth. Indeed, the social valid- It also involves evaluating negative outcomes and undesired

ity associated with matching interventions to perceived needs side effects that may result from using a method.

and desired outcomes is by its very nature weighted in unity By its very nature, declaring that a method is an objectively

with individuals’ subjective and personal opinions, attitudes, verified effective practice involves evaluation. Consumers of

and perceptions of the objectives, outcomes, procedures, and these methods are urged to judge them on both the basis of

cost effectiveness of potentially using a particular method. the reported scientific merits and the demonstrated utility with

Moreover, because social validation is predictably slanted to- individual students. It is insufficient to accept that a method-

ward individuals’ perceived notions of practical and pragmatic ology is an objectively verified effective practice solely on the

relative benefits, such as quality-of-life factors, social validity basis of published or reported research results. Equally impor-

should be considered relative to its perceived practical benefit, tant is determining, via ongoing data collection, whether the

rather than judged solely on the basis of quantitative or em- method results in positive outcomes with individual students.

pirical scientific findings. It is important to remember, how- The evaluation process with individual students includes

ever, that social validity is most effective when combined with three basic considerations: (a) How will the method be evalu-

a consideration of quantitative and other objectively verified ated, including how will student progress be demonstrated?

information, when intervention targets address basic and (b) Who will carry out the evaluations, and to whom will the

salient needs of students with ASD (i.e., social interaction, results be provided? and (c) How frequently will an evaluation

communication/language, behavioral) and when multiple of an intervention occur? Although the process appears mun-

judges who hold different stakeholder positions are inde- dane and conventional, specification of these elements will

pendently permitted to offer their subjective evaluative and structure and clarify the crucial evaluation process for various

perspective input. Although social validity in no way is a re- stakeholders.

placement for more objective and empirical evaluation of a Specifying the criteria that will be used to determine

method or procedure being considered for use with a student whether an intervention or treatment is effective and whether

with ASD, it does augment the methodology evaluation and the method should be continued also is an essential element

selection process by adding components that otherwise might of the assessment process. That different individuals associated

be neglected. with students with ASD will have different expectations and

perceptions related to the meaning of success, positive out-

come, and so forth is to be expected. Accordingly, clarification

Question 2 of at least the broad parameters of standards and criteria by

The second question asks, What are the potential risks associ- which a procedure will be judged is vitally important.

ated with the practice? This query includes consideration of

any possible negative outcomes or side effects associated with

using a method, including health, behavioral, and quality-of- Current Best Practices for

life risks for a student. It also includes consideration of poten- Students With ASD

tial parent- and family-related quality-of-life considerations.

For example, a family considering implementation of a highly Clearly there is a decided and dramatic need for identification

intensive and long-term discrete trial training method with a and use of scientifically based and effective practice methods.

young child with autism should be assisted in considering the Positive and expected outcomes occur when knowledgeable

cost, time, and possible effect on the family of implementing and skilled professionals, in collaboration with parents and

such a program. families, use methods that have objectively verified efficacy. As

This question also includes consideration of what options anyone who has ever worked with a student with an ASD can

would be excluded if a particular method were to be adopted. attest, however, successful outcomes require not only that an

Teams of professionals and parents do not have unlimited effective method be chosen but also that it be properly

amounts of time and opportunities to work with children and matched to the needs of a particular student and the planning

youth with ASD. Accordingly, adoption of a particular method team. Furthermore, the strategy can be expected to work ef-

often means that an alternative approach cannot be used. fectively only if it is correctly applied by a knowledgeable pro-

Hence, pragmatic and realistic consideration of intervention fessional or group of professionals. Indeed, without treatment

methods requires that teams of parents and professionals care- fidelity, wherein methods are correctly, consistently, and care-

fully compare methods and strategy options and consider the fully implemented using all prescribed practices, procedures,

consequences of dropping one alternative in favor of another. steps, and techniques required for promised results, even the

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at LAKEHEAD UNIV on March 13, 2015

VOLUME 20, NUMBER 3, FALL 2005

145

most effective technique will likely be unable to deliver ex- in the interpersonal relationship, physiological/biological/

pected outcomes (Cook & Schirmer, 2003; Detrich, 1999; neurological (prescription medications are not included), and

Lang & Fox, 2003). “other” categories. Within the skill-based category, applied be-

It is also increasingly evident that there is no single best- havior analysis (Alberto & Troutman, 2003; Anderson & Ro-

suited and universally effective method for all children and manczyk, 1999), discrete trial training (rated independent of

youth with ASD. The best programs appear to be those that applied behavior analysis; Maurice, Green, & Luce, 1996), and

incorporate a variety of objectively verified practices and that pivotal response training (Koegel, Koegel, Harrower, & Car-

are designed to address and support the needs of individual ter, 1999) were judged to meet the standard of scientifically

students and the professionals and families with whom they are based practices. This was also the case for Learning Experiences:

linked (National Research Council, 2001; Olley, 1999). An Alternative Program for Preschoolers and Parents (LEAP;

The field of ASD is unmistakably in its infancy stage, but Strain & Hoyson, 2000), which was included in the cognitive

there are basic intervention and treatment methods that ap- category. Two options, holding therapy (Welch, 1988) and

pear to have the capacity to serve as the foundation for success- facilitated communication (Biklen, 1993; Biklen & Schubert,

ful educational programs for students with ASD. As previously 1991) were perceived to meet the criteria for the not recom-

noted, effective practices are ultimately those that are system- mended classification (i.e., they were judged to lack efficacy

atically and objectively verified, are used with fidelity, and are and had the potential to be harmful).

tailored to fit the individual needs of students. In this context, Although important efforts were made to ensure impar-

the following methods were evaluated solely on the basis of tiality and objectivity, the evaluations, as with similar projects

their perceived objective, scientific, and effective-practice mer- (National Research Council, 2001), were likely affected to

its. The ultimate utility of these interventions and treatments some extent (albeit unknowingly) by the reviewers’ percep-

is a function of their alignment with the needs of individual tions and experiences. Similar undertakings of this nature will,

students, as well as program planners and implementers, and in all likelihood, reflect the overt and unconscious biases of the

the extent to which they are used in the prescribed fashion by persons who make the judgments. Yet, in spite of the inherent

appropriately trained, knowledgeable personnel. partiality and bias that accompany methodology assessments,

The reviews are based on work undertaken by Simpson this process is crucial. Indeed, the field will be unable to move

et al. (2005). This team evaluated 33 commonly used inter- forward unless it first prudently and systematically undertakes

ventions and treatments for children and youth with ASD. the difficult task of identifying objectively verifiable methods

They organized the methods into five categories: interpersonal and strategies that have the greatest probability of producing

relationship, skill based, cognitive, physiological/biological/ desired outcomes with students with autism-related disabili-

neurological, and other. In addition to describing each ASD ties. Complete agreement and total consensus will likely never

method, their intervention and treatment evaluations included be achieved. Nevertheless, the development of methodology

the following considerations: (a) reported outcomes and ef- evaluation processes focused on identifying objectively verifi-

fects; (b) qualifications of persons implementing the interven- able effective methods bodes well for students with ASD and

tion or treatment; (c) how, where, and when the intervention is a crucial first step in moving the field to a point of basic

or treatment is best administered; (d) potential risks associated agreement on methods and procedures that should be in place

with the intervention or treatment; (e) costs associated with for all students.

using the intervention or treatment; and (f ) methods for eval- Initial steps have already been taken in this direction. For

uating the effectiveness of the method. On the basis of these example, the Committee on Educational Interventions for

factors, the 33 interventions and treatments were graded as Children with Autism, Division of Behavioral and Social Sci-

falling within one of four categories: (a) scientifically based, ences and Education, National Research Council (2001) iden-

(b) promising practice, (c) practice having limited supporting tified a list of general characteristics perceived to be associated

information, or (d) not recommended (Simpson et al., 2005). with effective educational programs for children with ASD:

Scientifically based practices were recognized as those that have

“significant and convincing empirical efficacy and support” early [age] entry into an intervention program; active engage-

(p. 9). Promising practices were those methods that emerged ment in intensive instructional programming for the equivalent

of a full school day, including services that may be offered in dif-

as having “efficacy and utility with individuals with ASD”

ferent sites, for a minimum of five days a week with full-year pro-

(p. 9), even though the intervention requires additional objec-

gramming; use of planned teaching opportunities, organized

tive verification. Practices with limited supporting information around relatively brief periods of time for the youngest children

were those that lacked objective and convincing supporting (e.g., 15–20 minute intervals); and sufficient amounts of adult at-

evidence but had undecided, possible, or potential utility and tention in one-to-one or very small group instruction to meet in-

efficacy. The classification not recommended was used for in- dividualized goals. (p. 6)

terventions and treatments that were perceived to lack efficacy

and that might have the potential to be harmful. These preliminary and basic recommendations now must

The results of the evaluation process are summarized in be expanded, confirmed, and refined, and specific method-

Table 1. As noted, no perceived scientifically based practices fell ologies must be subjected to well-thought-out and objective

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at LAKEHEAD UNIV on March 13, 2015

146

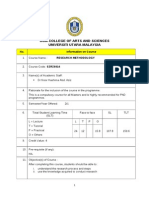

TABLE 1

Evaluation of Interventions and Treatments for Learners With Autism Spectrum Disorders

Intervention and Treatment Categories

Physiological/

Interpersonal biological/

Classification relationship Skill-based Cognitive neurological Other

Scientifically based • Applied behavior analysis • Learning Experi-

practice (Hagopian, Crockett, van ences: An Alter-

Stone, DeLeon, & Bowman, native Program

2000) for Preschoolers

• Discrete trial teaching and Parents

(Committee on Educational (Strain &

Interventions for Children Hoyson, 2000)

with Autism, 2001)

• Pivotal response training

(Hupp & Reitman, 2000)

Promising practice • Play-oriented • Picture Exchange Commu- • Cognitive be- • Sensory integra-

strategies nication System (Pyramid havioral modifi- tion (Case-Smith &

Educational Consultants, cation (Zirpoli, Bryant, 1999)

2005) 2005)

• Incidental teaching (Char- • Cognitive learn-

lop-Christy & Carpenter, ing strategies

2000) (Bock, 1999)

• Structured teaching (e.g., • Social stories

TEACCH; Panerai, Ferrante, (Rogers &

Caputo, & Impellizzeri, Myles, 2001)

1998) • Social decision-

• Augmentative alternative making strate-

communication (Ogletree, gies (Myles &

1998) Simpson, 2003)

• Assistive technology (Tjus,

Hinmann, & Nelson, 2001)

• Joint action routines

(Prizant, Wetherby & Rydell,

2000)

Limited supporting • Gentle teaching (Fox, • Van Dijk curricular approach • Cognitive • Scotopic sensitiv- • Music ther-

information for Dunlop, & Busch- (MacFarland, 2001) scripts (Krantz & ity syndrome: Irlen apy (Brown-

practice baker, 2000) • Fast ForWord (Gillam, Loeb, McClannahan, lenses (Griffin, well, 2002)

• Option method (e.g., & Friel-Patti, 2001) 1998) Christenson, Wes- • Art therapy

Son-Rise program; • Cartooning son, & Erickson, (Kornreich &

Option Institute and (Rogers & 1997) Schimmel,

Fellowship, 2004) Myles, 2001) • Auditory integra- 1991)

• Floor time (Green- • Power cards tion training (Mud-

span & Wieder, 2000) (Gagnon, 2001) ford et al., 2000)

• Pet/animal therapy • Megavitamin ther-

(McKinney, Dustin, & apy (Adams &

Wolff, 2001) McGinnis, 2001)

• Relationship devel- • Feingold diet (Tsai,

opment intervention 1998)

(Gustein & Sheely, • Herb, mineral, and

2002) other supple-

ments (Tolbert,

Haigler, Wairs, &

Dennis, 1993)

Not recommended • Holding therapy (Wa- • Facilitated communication

terhouse, 2000) (Perry, Bryson, & Bebko,

1998)

Note. Adapted from Simpson, R., de Boer-Ott, S., Griswold, D., Myles, B., Byrd, S., Ganz, J., et al. (2005). Autism spectrum disorders: Interventions and treat-

ments for children and youth. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. Used with permission of Corwin Press.

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at LAKEHEAD UNIV on March 13, 2015

VOLUME 20, NUMBER 3, FALL 2005

147

assessment. It is highly likely that time will confirm that there Algozzine, R. (2003). Scientifically based research: Who let the dogs

are no universally effective strategies and methodologies and out? Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 28(3),

that individual students will respond differently to different 156–160.

strategies. Yet, if basic elements of effective programming are Allbritten, D., Mainzer, R., & Ziegler, D. (2004). Will students with

not incorporated into interventions and treatments and pro- disabilities be scapegoats for school failures? Teaching Exceptional

Children, 36(3), 73–75.

grams are not based on objectively verifiable effective meth-

Autism Society of America. (2005). What is autism? Retrieved Feb-

ods, children and youth with ASD will fail to achieve outcomes

ruary 8, 2005, from http://autism-society.org

that fully reflect their capabilities.

Bettelheim, B. (1967). The empty fortress: Infantile autism and the

birth of self. New York: Free Press.

Biklen, D. (1993). Communication unbound: How facilitated com-

Summary munication is challenging traditional views of autism and ability/

disability. New York: Teachers College Press.

Children and youth with ASD have noticeably poor prognoses Biklen, D., & Schubert, A. (1991). New words: The communication

compared to other groups of students with disabilities. They of students with autism. Remedial and Special Education, 12(6),

also have the dubious distinction of regularly and commonly 46–57.

being exposed to intervention and treatment programs and Bock, M. A. (1999). Sorting laundry: Categorization application to

strategies that lack efficacy and demonstrating relatively poor an authentic learning activity by children with autism. Focus on

responses to intervention and treatment efforts. Accordingly, Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 14, 220–230.

there is an unmistakable need for objectively verifiable effec- Browder, D., & Cooper-Duffy, K. (2003). Evidence-based practices

for students with severe disabilities and the requirements for ac-

tive methods that can serve as the underpinning for every stu-

countability in No Child Left Behind. The Journal of Special Edu-

dent’s program. This process will be complicated and at times

cation, 37(3), 157–163.

tedious, it will be encumbered and affected by political and

Brownwell, M. D. (2002). Music adapted social stories to modify be-

legislative actions, and it will likely never result in total con- haviors in students with autism: Four case studies. Journal of Music

sensus. Yet, the need to identify effective methods is so im- Therapy, 39, 117–124.

portant that the field will not be able to move forward without Case-Smith, J., & Bryan, T. (1999). The effects of occupational ther-

significant progress in this area. apy with sensory integration emphasis on preschool-age children

with autism. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 53, 489–

497.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR Center on Educational Policy. (2003). From the capitol to the class-

room: State and federal efforts to implement the No Child Left Be-

Richard L. Simpson is a professor of special education at the University

hind Act. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved February 24, 2005,

of Kansas. He currently directs several federally funded projects that pre-

from http://www.ctredpol.org/pubs/nclbfullreportjan2003.pdf

pare professionals in effective practice methods for children and youth

with autism spectrum disorders. Address: Richard L. Simpson, Depart- Charlop-Christy, M. H., & Carpenter, M. H. (2000). Modified in-

ment of Special Education, JR Pearson Hall, 1122 W. Campus Road, cidental teaching sessions: A procedure for parents to increase

University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS 66045-3101; e-mail address: spontaneous speech in their children with autism. Journal of Posi-

richsimp@ku.edu tive Behavior Interventions, 2, 98–112.

Committee on Educational Interventions for Children with Autism.

(2001). Educating children with autism. Washington, DC: Na-

REFERENCES tional Academy Press.

Cook, B. G., & Schirmer, B. R. (2003). What is special about spe-

Adams, J., & McGinnis, W. (2001). Vitamins, minerals & autism. cial education? Overview and Analysis, 37, 200–205.

Advocate, 34(4), 21–22. Council for Excellence in Government. (2002). Coalition for evidence-

Alberto, P., & Troutman, A. (2003). Applied behavior analysis for based policy. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved February 15, 2005,

teachers (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/Prentice Hall. from http://www.excelgov.org/

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical Detrich, R. (1999). Increasing treatment fidelity by matching inter-

manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: ventions to contextual variables within educational settings. School

Author. Psychology Review, 28(4), 608–620.

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2004). Evidence- Egnor, D. (2003). Implications for special education policy and prac-

based practice in communication disorders: An introduction. Rock- tice. Principal Leadership, 3(7), 10–13.

ville, MD: Author. Eisenhart, M., & Towne, L. (2003). Contestation and change in na-

Anderson, S. R., & Romanczyk, R. (1999). Early intervention for tional policy on “scientifically based” education research. Educa-

young children with autism: Continuum-based behavioral models. tional Researcher, 32(7), 31–38.

The Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Disabilities, Fox, L., Dunlop, G., & Buschbaker, P. (2000). Understanding and

24(3), 162–173. intervening with children’s challenging behavior: A comprehensive

Albrecht, S. F., & Joles, C. (2003). Accountability and access to op- approach. In A. M. Wetherby & B. M. Prizant (Eds.), Autism spec-

portunity: Mutually exclusive tenets under a high-stakes testing trum disorders: A transactional development perspective (pp. 307–

mandate. Preventing School Failure, 47(2), 86–91. 332). Baltimore: Brookes.

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at LAKEHEAD UNIV on March 13, 2015

FOCUS ON AUTISM AND OTHER DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES

148

Frith, U. (2003). Autism: Explaining the enigma. Oxford, UK: Black- Maag, J. (2004). Behavior management: From theoretical implications

well Publishing. to practical applications. Belmont, CA: Thomson/Wadsworth.

Gagnon, E. (2001). Power cards: Using special interests to motivate MacFarland, S. (2001). Overview of the van Dijk curricular approach.

children and youth with Asperger syndrome and autism. Shawnee Retrieved January 19, 2004, from www.tr.wou.edu/dblink/

Mission, KS: Autism Asperger. VANDIJK12.htm

Gillam, R. B., Loeb, D. F., & Friel-Patti, S. (2001). Looking back: Maurice, C., Green, G., & Luce, S. (1996). Behavioral intervention

A summary of five exploratory studies of Fast ForWord. American for young children with autism: A manual for parents and profes-

Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 10, 269–273. sionals. Austin, TX: PRO-ED.

Greenspan, S. I., & Wieder, S. (2000). A developmental approach to Mayer-Johnson Inc. (2001). Boardmaker. Solana Beach, CA: Au-

difficulties in relating and communication in autism spectrum dis- thor.

orders and related syndromes. In A. M. Wetherby & B. M. Prizant McKinney, A., Dustin, D., & Wolff, R. (2001). The promise of dol-

(Eds.), Autism spectrum disorders: A transitional developmental phin assisted therapy. Parks and Recreation, 36(5), 46–50.

perspective (pp. 279–303). Baltimore: Brookes. Mudford, O. C., Cross, B. A., Breen, S., Cullen, C., Reeves, D.,

Gresham, F., Beebe-Frankenberger, M., & MacMillan, D. (1999). A Gould, J., et al. (2000). Auditory integration training for children

selective review of treatments for children with autism: Description with autism: No behavioral benefits detected. American Journal

and methodological considerations. School Psychology Review, 28(4), on Mental Retardation, 105, 118–129.

559–575. Myles, B. S., & Simpson, R. L. (2003). Asperger syndrome: A guide

Griffin, J. R., Christenson, G., Wesson, M., & Erickson, G. B. for educators and parents. Austin, TX: PRO-ED.

(1997). Optometric management of reading dysfunction. Boston: National Research Council. (2001). Educating children with autism.

Butterworth-Heinemann. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Gustein, S. E., & Sheely, R. K. (2002). Relationship development in-

No Child Left Behind Act of 2001. 20 U.S.C. 70 § 6301 et seq.

tervention with children, adolescents and adults. London: Jessica

(2002).

Kingsley.

Odom, S., Brantinger, E., Gersten, R., Horner, R., Thompson, B.,

Hagopian, L. P., Crockett, J. L., van Stone, M., DeLeon, I. G., &

& Harris, K. (2005). Research in special education: Scientific meth-

Bowman, L. G. (2000). Effects of noncontingent reinforcement

ods and evidence-based practices. Exceptional Children, 71(2), 137–

on problem behavior and stimulus engagement: The role of satia-

148.

tion, extinction and alternative reinforcement. Journal of Applied

Ogletree, B. T. (1998). The communicative context of autism. In

Behavior Analysis, 33, 433–448.

R. Simpson & B. Myles (Eds.), Educating children and youth with

Heflin, J., & Simpson, R. (1998). Interventions for children and

autism (pp. 141–172). Austin, TX: PRO-ED.

youth with autism: Prudent choices in a world of exaggerated

Olley, G. (1999). Curriculum for students with autism. School Psy-

claims and empty promises. Part II: Legal policy analysis and rec-

chology Review, 28(4), 595–607.

ommendations for selecting interventions and treatments. Focus on

Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 13(4), 212–220. Option Institute and Fellowship. (2004). The Son-Rise program: For

Heflin, J., & Simpson, R. (2002). Understanding intervention con- families with special children [brochure]. Sheffield, MA: Author.

troversies. In B. Scheuermann & J. Webber (Eds.), Autism: Teach- Panerai, S., Ferrante, L., Caputo, V., & Impellizzeri, C. (1998). Use

ing does make a difference (pp. 248–277). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/ of structured teaching for treatment of children with autism and

Thomson. severe and profound mental retardation. Education and Training

Horner, R., Carr, E., Halle, J., McGee, G., Odom, S., & Wolery, M. in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities, 33, 376–

(2005). The use of single-subject research to identify evidence- 374.

based practice in special education. Exceptional Children, 71(2), Perry, A., Bryson, S., & Bebko, J. (1998). Brief report: Degree of

165–179. facilitator influence in facilitated communication as a function of

Kalb, C. (2005, February 28). When does autism start? Newsweek, facilitator characteristics, attitudes, and beliefs. Journal of Autism

pp. 44–53. and Developmental Disorders, 28, 87–90.

Koegel, L., Koegel, R., Harrower, J., & Carter, C. (1999). Pivotal Prizant, B., & Rubin, E. (1999). Contemporary issues in interven-

response intervention 1: Overview of approach. The Journal of the tions for autism spectrum disorders: A commentary. The Journal

Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, 24(3), 174–185. of the Association for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 24(3), 199–

Kornreich, T. Z., & Schimmel, B. F. (1991). The world is attacked 208.

by great big snowflakes: Art therapy with an autistic boy. Ameri- Prizant, B. M., Wetherby, A. M., & Rydell, P. J. (2000). Commu-

can Journal of Art Therapy, 29, 77–84. nication intervention issues for children with autism spectrum

Krantz, P., & McClannahan, L. (1998). Social interaction skills for disorders. In A. M. Wetherby & B. M. Prizant (Eds.), Autism spec-

children with autism: A script-fading procedure for beginning trum disorders: A transactional developmental perspective (pp. 193–

readers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 31, 191–202. 224). Baltimore: Brookes.

Lang, M., & Fox, L. (2003). Breaking with tradition: Providing ef- Pyramid Educational Consultants. (2005). The picture exchange com-

fective professional development for instructional personnel sup- munication system (PECS). Newark, DE: Author. Retrieved Febru-

porting students with severe disabilities. Teacher Education and ary 24, 2005, from http://www.pecs.com/index.html

Special Education, 26(1), 17–26. Robelen, E. W. (2002, January 9). An ESEA primer. Education Week,

Lerman, D., Vorndran, L., & Addison, L. (2004). Preparing teach- pp. 28–29.

ers in evidence-based practices for young children with autism. Rogers, M. F., & Myles, S. B. (2001). Using social stories and comic

School Psychology Review, 33(4), 510–526. strip conversations to interpret social situations for an adolescent

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at LAKEHEAD UNIV on March 13, 2015

VOLUME 20, NUMBER 3, FALL 2005

149

with Asperger syndrome. Intervention in School and Clinic, 36, with autism and mixed intellectual disabilities. Autism: The Inter-

310–313. national Journal of Research and Practice, 5, 175–187.

Sailor, W., & Stowe, M. (2003). The relationship of inquiry to pub- Tolbert, L., Haigler, T., Wairs, M., & Dennis, T. (1993). Brief report:

lic policy. Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, Lack of response in an autistic population to low-dose clinical trial

28(3), 148–152. of pyridoxine plus magnesium. Journal of Autism and Develop-

Shavelson, R. J., & Towne, L. (Eds). (2002). Scientific research in ed- mental Disorders, 23, 193–199.

ucation. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. Tsai, L. (1998). Medical interventions for students with autism. In

Sillman, E. (1995). Issues raised by facilitated communication for R. Simpson & B. Myles (Eds.), Educating children and youth with

theorizing and research on autism: Comments for Duchan’s (1993) autism (pp. 141–172). Austin, TX: PRO-ED.

tutorial. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 38, 204–206. U.S. Department of Education. (2003). Identifying and implement-

Simpson, R. (2004). Finding effective intervention and personnel ing educational practices supported by rigorous evidence: A user

preparation practices for students with autism spectrum disorders. friendly guide. Washington, DC: Author.

Exceptional Children, 70(2), 135–144. Volkmar, F., Cook, E., & Pomeroy, J. (1999a). Practice parameters

Simpson, R., de Boer-Ott, S., Griswold, D., Myles, B., Byrd, S., for the assessment and treatment of children, adolescents and

Ganz, J., et al. (2005). Autism spectrum disorders: Interventions adults with autism and other pervasive developmental disorders.

and treatments for children and youth. Thousand Oaks, CA: Cor- Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychia-

win Press. try, 38(12), 32S–54S.

Simpson, R., LaCava, P., & Graner, P. (2004). The No Child Left Volkmar, F., Cook, E., & Pomeroy, J. (1999b). Summary of the prac-

Behind Act (NCLB): Challenges and implications for educators. tice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children, ado-

Intervention in School and Clinic, 40(20), 67–75. lescents and adults with autism and other pervasive developmental

Simpson, R., & Myles, B. (1998). Controversial therapies and inter- disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adoles-

ventions with children and youth with autism. In R. L. Simpson & cent Psychiatry, 38(12), 32S–54S.

B. S. Myles (Eds.), Educating children and youth with autism Waterhouse, S. (2000). A positive approach to autism. London: Jes-

(pp. 315–331). Austin, TX: PRO-ED. sica Kingsley.

Smith, A. (2003). Scientifically based research and evidence-based Welch, M. G. (1988). Holding time. New York: Simon and Schuster.

education: A federal policy context. Research & Practice for Persons What Works Clearinghouse. (2004). A trusted source of scientific evi-

with Severe Disabilities, 28(3), 126–132. dence of what works in education. Retrieved February 15, 2005,

Strain, P., & Hoyson, M. (2000). The need for longitudinal, inten- from http://www.w-w-c.org/about.html

sive social skill intervention: LEAP follow-up outcomes for chil- What Works Clearinghouse. (2004). Design and implementation as-

dren with autism. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, sessment device. Retrieved February 15, 2005, from http://www

20(2), 116–122. .whatworks.ed.gov/reviewprocess/standards.html

Thompson, B., Diamond, K., McWilliam, R., Snyder, P., & Snyder, White, E., & Smith, C. (2002). Scientific research in education. Ed-

S. (2005). Evaluating the quality of evidence from correlational ucational Researcher, 31(8), 3–29.

research for evidence-based practice. Exceptional Children, 71(2), Wolf, M. (1978). Social validity: The case for subjective measurement

181–194. of how applied behavior analysis is finding its heart. Journal of Ap-

Tjus, T., Hinmann, M., & Nelson, K. E. (2001). Interaction patterns plied Behavior Analysis, 11, 203–214.

between children and their teachers when using a specific multi- Zirpoli, T. J. (2005). Behavior management: Applications for teachers.

media and communication strategy: Observations from children Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson-Merrill/Prentice Hall.

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at LAKEHEAD UNIV on March 13, 2015

You might also like

- Autism and The Grand Challenges in Global Mental HealthDocument4 pagesAutism and The Grand Challenges in Global Mental HealthKarel GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Acceptability of and Resistance To Applied Behavioural Analysis and Other Behaviour TechniquesDocument16 pagesAcceptability of and Resistance To Applied Behavioural Analysis and Other Behaviour TechniquesRacheleNo ratings yet

- Evidence Based Practices For Young Children With AutismDocument11 pagesEvidence Based Practices For Young Children With Autismkonyicska_kingaNo ratings yet

- Article 2023 EnquestesDocument9 pagesArticle 2023 EnquestespaulacamposorpiNo ratings yet

- Autism Treatment Survey: Services Received by Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders in Public School ClassroomsDocument11 pagesAutism Treatment Survey: Services Received by Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders in Public School ClassroomsLIZETH FERNANDA VILLEGAS ZULUAGANo ratings yet

- Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders: Shin-Yi Wang, Ying Cui, Rauno ParrilaDocument8 pagesResearch in Autism Spectrum Disorders: Shin-Yi Wang, Ying Cui, Rauno ParrilaYusrina Ayu FebryanNo ratings yet

- Are Zero Tolerance Policies Effective in SchsDocument11 pagesAre Zero Tolerance Policies Effective in SchsEducation JusticeNo ratings yet

- Effects of Anti-Stigma CampaignDocument15 pagesEffects of Anti-Stigma Campaignkiki lovemeNo ratings yet

- Keywords: Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Young Children, ChallengDocument20 pagesKeywords: Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Young Children, ChallengKristin Lancaster WheelerNo ratings yet

- 01 Clinical Change Mechanisms in The Treatment of College StudentsDocument17 pages01 Clinical Change Mechanisms in The Treatment of College StudentsaamandadonedaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0005789423000370 MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S0005789423000370 MainAli JNo ratings yet

- Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders: Matthew J. Segall, Jonathan M. CampbellDocument12 pagesResearch in Autism Spectrum Disorders: Matthew J. Segall, Jonathan M. CampbellMattNo ratings yet

- Howlin197783 AcceptedDocument11 pagesHowlin197783 AcceptedMark Anthony PanahonNo ratings yet

- Revisión SistemáticaDocument14 pagesRevisión SistemáticaSofia DibildoxNo ratings yet

- Autism Interventions A Critical UpdateDocument7 pagesAutism Interventions A Critical UpdateHumaira MalikNo ratings yet

- Medical Students Perceptions Awareness Societal Attitudes and Knowledge of Autism Spectrum Disorder An Exploratory Study in MalaysiaDocument11 pagesMedical Students Perceptions Awareness Societal Attitudes and Knowledge of Autism Spectrum Disorder An Exploratory Study in MalaysiaHobieNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Autism and InclusionDocument5 pagesDissertation Autism and InclusionBuyCollegePapersSingapore100% (1)

- Incredible Years ProgramDocument11 pagesIncredible Years ProgramKallia KoufakiNo ratings yet

- Anderson Et Al. - 2018 - Building Capacity To Support Students With AutismDocument33 pagesAnderson Et Al. - 2018 - Building Capacity To Support Students With AutismIanovici Daniela MirelaNo ratings yet

- Impact of Ibi Paper - Veleno - Final Draft - ModifiedDocument22 pagesImpact of Ibi Paper - Veleno - Final Draft - Modifiedapi-163017967No ratings yet

- National Council On Family Relations Family RelationsDocument15 pagesNational Council On Family Relations Family Relationsmoses machiraNo ratings yet

- Knowledge and Reported Use of Evidence Based PracticesDocument12 pagesKnowledge and Reported Use of Evidence Based PracticesmhabranNo ratings yet

- Trends and models in school-based occupational therapyDocument22 pagesTrends and models in school-based occupational therapyJenny RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Evidenced-Based Interventions for Children with AutismDocument16 pagesEvidenced-Based Interventions for Children with AutismDarahttbNo ratings yet

- Multidisciplinary Teamwork in Autism: Can One Size Fit All?: Karola DillenburgerDocument17 pagesMultidisciplinary Teamwork in Autism: Can One Size Fit All?: Karola DillenburgerMoustafa AbdouNo ratings yet

- The Role of The School Psychologist in The Inclusive EducationDocument20 pagesThe Role of The School Psychologist in The Inclusive EducationCortés PameliNo ratings yet

- Inclusion of Learners With Autism Spectrum Disorders in General Education SettingsDocument18 pagesInclusion of Learners With Autism Spectrum Disorders in General Education SettingsSara BenitoNo ratings yet

- A Meta Synthesis of How Parents of Children With Autism Describe Their Experience of Advocating For Their Children During The Process of DiagnosisDocument15 pagesA Meta Synthesis of How Parents of Children With Autism Describe Their Experience of Advocating For Their Children During The Process of DiagnosisKarel Guevara100% (1)

- Ebp in Health EducationDocument25 pagesEbp in Health EducationPablito NazarenoNo ratings yet

- Occupational Therapists Prefer Combining PDFDocument12 pagesOccupational Therapists Prefer Combining PDFSuperfixenNo ratings yet

- 6 - A Review On Measuring Treatment Response in Parent-Mediated Autism Early InterventionsDocument16 pages6 - A Review On Measuring Treatment Response in Parent-Mediated Autism Early InterventionsAlena CairoNo ratings yet

- A Systematic Review of Predictors, Moderators, and Mediators of Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) Outcomes For Children With Autism Spectrum DisorderDocument12 pagesA Systematic Review of Predictors, Moderators, and Mediators of Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) Outcomes For Children With Autism Spectrum DisorderOrnella ThysNo ratings yet

- Wicked Problems in Health Professions EdDocument12 pagesWicked Problems in Health Professions EdSamar AboulsoudNo ratings yet

- Screening For Social Emotional Concerns: Considerations in The Selection of Instruments January 2009Document18 pagesScreening For Social Emotional Concerns: Considerations in The Selection of Instruments January 2009healthoregon100% (1)

- CoachingDocument15 pagesCoachingHec ChavezNo ratings yet

- Article - INFUSION - OF - AGE-FRIENDLY - PRINCIPLES - INTO - CURRICULADocument1 pageArticle - INFUSION - OF - AGE-FRIENDLY - PRINCIPLES - INTO - CURRICULAHarlene ArabiaNo ratings yet

- Boshoff 2018Document15 pagesBoshoff 2018Thaís Spall ChaximNo ratings yet

- Handbook of Parent-Implemented Interventions For Very Young Children With AutismDocument497 pagesHandbook of Parent-Implemented Interventions For Very Young Children With AutismLudmilaCândido100% (1)

- 2019 Dunn e Foley Qualitative Research - Perceptions of The Developmental, Individual Differences, Relationship-Based (DIR) Model Among Preschool Staff in A Public-School SettingDocument11 pages2019 Dunn e Foley Qualitative Research - Perceptions of The Developmental, Individual Differences, Relationship-Based (DIR) Model Among Preschool Staff in A Public-School SettingLaisy LimeiraNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Community-Based Early Intervention For Childrens With Autism Spectrum Disorder. A Meta-AnalysisDocument10 pagesEffectiveness of Community-Based Early Intervention For Childrens With Autism Spectrum Disorder. A Meta-AnalysisLucas De Almeida MedeirosNo ratings yet

- Preparing Tomorrow's Doctors To Care For Patients With Autism - 2016Document15 pagesPreparing Tomorrow's Doctors To Care For Patients With Autism - 2016Karel GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Kaminski Clausse (2017)Document24 pagesKaminski Clausse (2017)Nuria Moreno RománNo ratings yet

- fasd-intervention-2009Document21 pagesfasd-intervention-2009api-739840251No ratings yet

- EBP Parent Summary Apr2009Document19 pagesEBP Parent Summary Apr2009wholesoulazNo ratings yet

- Mcpherson 2016Document11 pagesMcpherson 2016shafyd ramdanNo ratings yet

- CH 81 Assessment in Early Childhood Instruction Focused Strategies To Support Response To Intervention Frameworks PDFDocument11 pagesCH 81 Assessment in Early Childhood Instruction Focused Strategies To Support Response To Intervention Frameworks PDFVasia PapapetrouNo ratings yet

- Template - Artikel 1 - No Absen 1 S.D 8Document12 pagesTemplate - Artikel 1 - No Absen 1 S.D 8Angelica EarlyanaNo ratings yet

- TTo TSH en Enfoque EscolarDocument15 pagesTTo TSH en Enfoque EscolarCamila AlejandraNo ratings yet

- Cheak-Zamora, N. C., Teti, M. and First, J. (2015) - Transitions Are Scary For Our Kids, and They'Re Scary For Us' Family Member and Youth Perspectives On The Challenges of Transitioning ToDocument13 pagesCheak-Zamora, N. C., Teti, M. and First, J. (2015) - Transitions Are Scary For Our Kids, and They'Re Scary For Us' Family Member and Youth Perspectives On The Challenges of Transitioning ToTomislav CvrtnjakNo ratings yet

- Errorless Compliance Training DucharmeDocument9 pagesErrorless Compliance Training DucharmerarasNo ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Review of Interventions For Autism Used in or of Relevance To Occupational TherapyDocument14 pagesEvidence-Based Review of Interventions For Autism Used in or of Relevance To Occupational TherapyGabriela LalaNo ratings yet

- Adherencia TerapeuticaDocument14 pagesAdherencia TerapeuticaEykiAmaroMuñozZuritaNo ratings yet

- Testing and Beyond - Strategies and Tools For Evaluating and Assessing Infants and ToddlersDocument25 pagesTesting and Beyond - Strategies and Tools For Evaluating and Assessing Infants and ToddlersMargareta Salsah BeeNo ratings yet

- Clinician Perspectives On Telehealth Assessment of Autism Spectrum Disorder During The COVID-19 PandemicDocument16 pagesClinician Perspectives On Telehealth Assessment of Autism Spectrum Disorder During The COVID-19 PandemicrenatoNo ratings yet

- TVL Students Challenges in Performance Task Despite Modular Distance Learning ModalityDocument9 pagesTVL Students Challenges in Performance Task Despite Modular Distance Learning ModalityPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Sawyer 2010Document11 pagesSawyer 2010Đan TâmNo ratings yet

- Aur 2046Document14 pagesAur 2046Eduardo JordaoNo ratings yet

- NURS FPX4900 Roxy ObiesieElizabeth Assessment4PartB 1Document11 pagesNURS FPX4900 Roxy ObiesieElizabeth Assessment4PartB 1Jeffrey MwendwaNo ratings yet

- Outcome DIDocument8 pagesOutcome DIarifNo ratings yet

- Therapist's Guide to Pediatric Affect and Behavior RegulationFrom EverandTherapist's Guide to Pediatric Affect and Behavior RegulationNo ratings yet

- Free - Level 1 Instructions PDFDocument1 pageFree - Level 1 Instructions PDFMarta Balula DiasNo ratings yet

- GTD For Teens Vision CanvasDocument2 pagesGTD For Teens Vision CanvasMarta Balula DiasNo ratings yet

- GTD For Teens Goals Canvas PDFDocument2 pagesGTD For Teens Goals Canvas PDFMarta Balula DiasNo ratings yet

- GTD For Teens Clarify CanvasDocument2 pagesGTD For Teens Clarify CanvasMarta Balula DiasNo ratings yet

- Steiner Anthroposophy Background PDFDocument1 pageSteiner Anthroposophy Background PDFMarta Balula DiasNo ratings yet

- ACTS SWSF Project HandbookDocument45 pagesACTS SWSF Project HandbookMarta Balula DiasNo ratings yet

- Lifecycle PlantDocument8 pagesLifecycle PlantMarta Balula Dias100% (1)

- The Archimedes Forest Schools Model PDFDocument172 pagesThe Archimedes Forest Schools Model PDFMarta Balula DiasNo ratings yet

- Folheto SoundsoryDocument2 pagesFolheto SoundsoryMarta Balula DiasNo ratings yet

- How to Help Your Child with Learning Problems NOWDocument6 pagesHow to Help Your Child with Learning Problems NOWMarta Balula DiasNo ratings yet

- Discourse Analysis DA and Content AnalysDocument2 pagesDiscourse Analysis DA and Content AnalysBadarNo ratings yet

- The Marketing Research Process and Defining The Problem and Research ObjectivesDocument29 pagesThe Marketing Research Process and Defining The Problem and Research ObjectivesnotsaudNo ratings yet

- 2964 CONSORT+2010+ChecklistDocument3 pages2964 CONSORT+2010+ChecklistNur UlayatilmiladiyyahNo ratings yet

- Distribusi Soal Statistik I Tahun Akademik 2022/2023Document2 pagesDistribusi Soal Statistik I Tahun Akademik 2022/2023yangbaca nyemotNo ratings yet

- PRISMA Extension For Scoping Reviews PRISMA SCRDocument19 pagesPRISMA Extension For Scoping Reviews PRISMA SCRJhon OrtizNo ratings yet

- Lect19b Mills Method SlidespdfDocument8 pagesLect19b Mills Method SlidespdfLuc ChiassonNo ratings yet

- PR1 Chapter 3 English 2Document2 pagesPR1 Chapter 3 English 2raizhendesalit2No ratings yet

- Title Proposal Form For StudentsDocument3 pagesTitle Proposal Form For StudentsHelen AlalagNo ratings yet

- 3 - Research Instrument, Validity, and ReliabilityDocument4 pages3 - Research Instrument, Validity, and ReliabilityMeryl LabatanaNo ratings yet

- A Mixed Methods Design To Investigate Student Outcomes Based On Parental Attitudes, Beliefs, and Expectations in Mathematics EducationDocument16 pagesA Mixed Methods Design To Investigate Student Outcomes Based On Parental Attitudes, Beliefs, and Expectations in Mathematics EducationChristine VillarinNo ratings yet

- Real Statistics Using Excel - Examples Workbook Charles Zaiontz, 9 April 2015Document1,595 pagesReal Statistics Using Excel - Examples Workbook Charles Zaiontz, 9 April 2015Maaraa MaaraaNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of Qualitative Research MethodsDocument5 pagesCharacteristics of Qualitative Research Methodsshabnam100% (1)

- Analytical Method DevelopmentDocument3 pagesAnalytical Method DevelopmentMohanad AlashkarNo ratings yet

- Epistemological Integration, Essentials of An Islamic MethodologyDocument367 pagesEpistemological Integration, Essentials of An Islamic MethodologyPddfNo ratings yet

- SMDM Project Report: Submitted By: Kratika VijayvergiyaDocument15 pagesSMDM Project Report: Submitted By: Kratika VijayvergiyaKratika VijayvergiyaNo ratings yet

- RM MBA-Sem-I 2018Document1 pageRM MBA-Sem-I 2018yogeshgharpureNo ratings yet

- Chapter-5 Explorartory Research DesignDocument27 pagesChapter-5 Explorartory Research DesignAyushman UpretiNo ratings yet

- UUM Research MethodologyDocument8 pagesUUM Research MethodologySuhamira NordinNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9 (Compatibility Mode)Document26 pagesChapter 9 (Compatibility Mode)Thomas AndersonNo ratings yet

- Research Final Format G 12Document22 pagesResearch Final Format G 12Gwaps KoNo ratings yet

- Simple Project Risk Management PlanDocument19 pagesSimple Project Risk Management PlanBAMLAKE ALEMAYEHUNo ratings yet

- HMEF5113 Statistics For Educational ResearchDocument234 pagesHMEF5113 Statistics For Educational ResearchLily Ng100% (1)

- Psmim Midterm Module 1Document14 pagesPsmim Midterm Module 1joan MangadaNo ratings yet

- Draft Lesson Plan Week 7-Sok Saran Nov 12, 2020Document4 pagesDraft Lesson Plan Week 7-Sok Saran Nov 12, 2020Sran LouthNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of ResearchDocument23 pagesCharacteristics of ResearchJoana CabatañaNo ratings yet

- The PHD Proofreaders Writing Template-1Document1 pageThe PHD Proofreaders Writing Template-1HarsanoJayadi100% (1)

- PR2 Q1 Module1Document10 pagesPR2 Q1 Module1Edison MontemayorNo ratings yet

- Struggles of Students Who Live in A Far Flung Areas PR1Document27 pagesStruggles of Students Who Live in A Far Flung Areas PR1vennehraitolNo ratings yet

- 5.practice Problems On Hypotheses Testing-One SampleDocument2 pages5.practice Problems On Hypotheses Testing-One Samplesamaya pypNo ratings yet

- Compsa (Midterm) ModuleDocument10 pagesCompsa (Midterm) ModuleJaypher PeridoNo ratings yet