Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Conversation - Unknown - Indigenous Constitutional Recognition The Concept of Consultation

Uploaded by

John0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

25 views4 pagesThis document discusses the concept of consultation in proposals for Indigenous constitutional recognition put forward by the Cape York Institute. Key points:

- An Indigenous body would be established in the constitution to provide advice to the Commonwealth parliament on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. This advice would be tabled but not binding.

- While a helpful proposal, the document notes that true consultation requires understanding, skills, and commitment - which are often lacking in Australian political culture.

- Several aspects of the proposal could be improved, such as ensuring consultation applies to all levels of government and actors affecting Indigenous peoples, not just the Commonwealth parliament. The placement of the proposal in the constitution could also be reconsidered.

Original Description:

Conversation - Unknown - Indigenous Constitutional Recognition the Concept of Consultation

Original Title

Conversation - Unknown - Indigenous Constitutional Recognition the Concept of Consultation

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis document discusses the concept of consultation in proposals for Indigenous constitutional recognition put forward by the Cape York Institute. Key points:

- An Indigenous body would be established in the constitution to provide advice to the Commonwealth parliament on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. This advice would be tabled but not binding.

- While a helpful proposal, the document notes that true consultation requires understanding, skills, and commitment - which are often lacking in Australian political culture.

- Several aspects of the proposal could be improved, such as ensuring consultation applies to all levels of government and actors affecting Indigenous peoples, not just the Commonwealth parliament. The placement of the proposal in the constitution could also be reconsidered.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

25 views4 pagesConversation - Unknown - Indigenous Constitutional Recognition The Concept of Consultation

Uploaded by

JohnThis document discusses the concept of consultation in proposals for Indigenous constitutional recognition put forward by the Cape York Institute. Key points:

- An Indigenous body would be established in the constitution to provide advice to the Commonwealth parliament on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. This advice would be tabled but not binding.

- While a helpful proposal, the document notes that true consultation requires understanding, skills, and commitment - which are often lacking in Australian political culture.

- Several aspects of the proposal could be improved, such as ensuring consultation applies to all levels of government and actors affecting Indigenous peoples, not just the Commonwealth parliament. The placement of the proposal in the constitution could also be reconsidered.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

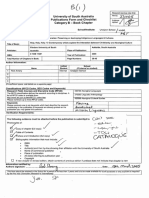

INDIGENOUS CONSTITUTIONAL RECOGNITION:

THE CONCEPT OF CONSULTATION

by Cheryl Saunders

INTRODUCTION the principal tools for ensuring compliance with principles of

I was asked to make some remarks about the concept of ‘consultation’ constitutionalism. It is vastly preferable to a watered down, purely

in the proposal for Indigenous constitutional recognition put symbolic version of the Expert Panel’s proposals3, if that proves

forward by the Cape York Institute (‘CPI’). My understanding of what to be the only alternative on offer.

presently is proposed is taken from the two submissions by the CPI

to the Joint Select Committee on Constitutional Recognition of I should make it clear, however, that I profoundly disagree with

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples (‘Joint Committee’)1 the description of the Constitution as a ‘procedural, practical

and from Anne Twomey’s very helpful piece in The Conversation, and pragmatic Charter of Government’ that accompanies the

translating these proposals into constitutional form. 2 justification for this proposal. That description denies the dignity

and significance of the institutions that the Constitution establishes,

The essential elements, as I understand them, are these: drawing on the potentially rich conception of Australian federal

• An Indigenous body would be required by the Constitution, democracy. And I also disassociate myself from the concerns about

with its composition, roles, powers and procedures provided the effects of a non-discrimination clause in the Constitution, which

in legislation. are not only exaggerated, but pay insufficient regard to the well-

• The body would provide ‘advice’ to the Commonwealth founded fears of Indigenous Australians about placing their faith

Parliament and government on what are described as ‘matters in the Australian political process alone.

relating’ to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

• The advice would be required to be tabled in the Parliament I agree with Anne Twomey that the proposal for an Indigenous

as soon as practicable, by the Prime Minister or the Speaker (in constitutional body can be drafted so as to be non-justiciable, at

principle, I prefer the latter). least as far as the giving and taking of advice are concerned, on the

• Both Houses would be required to ‘give consideration’ to the basis that this occurs within the lawmaking process. In the absence

advice in debating proposed laws with respect to Aboriginal of justiciability, however, the political process bears a heavy burden,

and Torres Strait Islander peoples. which must be discharged effectively if this form of constitutional

• The ‘advice’ would not be binding and the provisions would be recognition is to be meaningful.

drafted so as to be non-justiciable (although without expressly

saying so). To attempt to ensure that the political process is up to the task,

• The Indigenous body could be proactive as well as reactive, in the proposal relies on the transparency that would accompany

the sense of offering advice on any matters as it considered fit. the tabling of the Indigenous body’s advice in the Parliament,

• This new provision would be added to the Constitution in a coupled with the respect that the views of the Indigenous

new Chapter IA, immediately following the chapter on the body should attract, initially and over time. There are Australian

Parliament and preceding the chapter on the Executive. precedents for strategies of this kind. In its early years, the former

Administrative Review Council relied entirely on the persuasive

OBSERVATIONS quality of its tabled advice for its considerable influence over the

In my view, this is a helpful and constructive proposal, offering a direction of development of the administrative law system. In a

new and quite different approach to constitutional recognition, sense, the legislative bills of rights in Victoria and the Australian

which has some potential to be both effective and broadly Capital Territory also rely on transparency to ensure that the

acceptable. It fits with the distinctive focus of the Australian protected rights are taken into account when new legislation

Constitution on institutions and the organisation of power as is made.

INDIGENOUS LAW BULLETIN July / August, Volume 8, Issue 19 I 19

Nevertheless, if this proposal is to go forward it should be carefully any initiative affecting Indigenous Australians in any way, as long

designed in full understanding of the reality that the Australian as, at least, the body obtained information about the initiative early

political culture is indeed very bad at genuine consultation; either enough for its advice to have a chance of being effective.

with the public at large or with groups affected by particular

proposals. The history of dealings with Indigenous peoples is In relation to the obligation on the Commonwealth Parliament,

testament to this reality, which may be attributable to a shortfall there are several possible interpretations. One is that the obligation

in understanding of what effective consultation involves, in skills, is triggered only when legislation relies (solely?) on whatever head

or in commitment. The recent fate of self-government in Norfolk of power to legislate for Indigenous peoples replaces the ‘race’

Island is a recent illustration in a different context. power in section 51(xxvi). This would not, however, catch the

legislation authorising the intervention in the Northern Territory.

Several other aspects of the proposal also deserve further A second interpretation, which would do so, would require the

consideration from the standpoint of its reliance on consultation Commonwealth Parliament to consider any relevant advice in

or advice. making any law specifically for Indigenous peoples, whatever

the source of power for the legislation. A third (but on the face

First, in its present form, the proposal does not adequately take of the text less likely) interpretation, would trigger the obligation

account of the range of actors making decisions that affect to consider whenever legislation affected Indigenous people in

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, at various points in company with others albeit, perhaps, in a particular way.

the policy development cycle.

A third point, to some extent consequential on the earlier two,

is the proposed placement of the new provision in Chapter IA

Many parts of the world already of the Constitution. I acknowledge that this placement gives the

have in place much more formalised provision a prominence that fits with its significance. To the extent

procedures for consultation with that the consultative mechanism is associated solely with proposed

legislation passing through the Commonwealth Parliament, there

Indigenous peoples and other

also is some logic in placing the new provision immediately

structural minority groups. after the chapter on the Parliament. Interspersing a new chapter

amongst the first three chapters of the Constitution on which the

All levels of government exercise public power in ways that separation of powers depends is inelegant, however, from the

affect Indigenous peoples: the Commonwealth, the states, the standpoint of constitutional design. More significantly for present

territories and local government. Indigenous peoples are affected purposes, to the extent that the consultative mechanism ultimately

by policies given effect through executive, as well as legislative has wider effect—at all levels of government and on all public

action. Executive schemes reliant on spending, or contract, or decision-makers—this placement also may be misleading. Most

intergovernmental agreement are endemic in the Australian significantly of all, it may also be impolitic; encouraging (spurious)

system of government. The proposal to close down Indigenous claims that the Indigenous body gives an unfair advantage to

communities in the north of Western Australia, for example, Indigenous peoples in the legislative process or that, in some

involved funding decisions taken by both levels of government. unexplained way, it amounts to a third chamber of the legislature.

Within the executive branch, decisions are taken by a wide range

of actors, including Ministers, both individually and in Cabinet, An alternative placement might be in a new Chapter VIIA, in a

and bureaucrats. And even if consultation with the Indigenous new section 127, replacing the discriminatory provision that

body is confined to legislation, governments are committed to was removed in 1967 (and thus having a symbolism of its own).

the form and purpose of legislation well before proposals hit the The chapter heading might specifically refer to recognition. The

parliamentary floor. new section 127 might include the new power to legislate for

Indigenous peoples, in lieu of section 51(xxvi), followed by the

Secondly, it is not entirely clear to me when the consultative requirement for the establishment of the Indigenous advisory body

mechanisms will be triggered, on the proposal as it presently and an obligation on the Parliament to consider its advice, when

stands. I accept that the proposal is drafted so as to confer a it proposed to exercise the new power.4 This arrangement would

broader authority on the Indigenous body to give advice than on make it clear that the power and the obligation to consult were

the Commonwealth Parliament to take the advice into account. I linked; an impeccable arrangement, on any view. The Indigenous

assume that the former would entitle the body to give advice on body should still have the authority to advise on any aspect of

20 I INDIGENOUS LAW BULLETIN July / August, Volume 8, Issue 19

Australian governance affecting Indigenous people, and its advice the understanding in relation to the Sami Parliament.

should still be required to be tabled in the Parliament, but the • Public authorities are obliged to inform an Indigenous body

package might more readily be perceived as directed solely to the about all matters in this category, as early as possible in the

imperatives of recognition. decision-making process.

• Information about both agreement and lack of agreement

COMPARATIVE EXPERIENCE should be included in Cabinet documents and in parliamentary

Some insights into ways in which an approach to recognition proceedings.

that constitutionalised a mechanism for consultation might be • Regular meetings should be held between government leaders

both justified and strengthened can be drawn from comparative and the Indigenous body (or representatives of it).

experience.

INSIGHTS FOR AUSTRALIA

Many parts of the world already have in place much more The lessons of these insights for the Australian proposal are obvious.

formalised procedures for consultation with Indigenous peoples At the risk of repetition, however, they include the following:

and other structural minority groups, not only in order to give • A principal rationale (perhaps the rationale) for achieving

effect to international obligations but, even more importantly, constitutional recognition in this way lies in the contribution

as an obvious way of providing good governance. These include: that it makes to good government.

• Scandinavia, where consultation occurs with Sami Parliaments • ‘Consultation’ (or giving and receiving advice) involves a rich

in Finland, Norway and Sweden.5 and genuine process that is concerned with outcome as well

• Europe, pursuant to the Framework Convention on National as input; that is pursued in good faith; and that is undertaken

Minorities.6 with the goal of reaching agreement (even if the goal is not

• New Zealand, where there is a developed understanding of always realised).

what consultation with Maori involves, for decision-making • Consultation should take place whenever Indigenous interests

both within and outside the Treaty of Waitangi.7 are affected in a way that is distinctive and not shared by society

• Canada, where an obligation to consult has been associated as a whole, or other groups of it.

with the ‘honour of the Crown’, given apparent impetus by the • Consultation should be undertaken by any public actor making

1982 constitutional changes (section 35).8 decisions that affect Indigenous peoples in this way, at any

level of government.

Ideas and techniques that can be extracted from this experience • For consultation to be effective, information should be

with potential relevance for present purposes include the following: provided to the Indigenous body at the start of a policy process.

• Consultation can be equated with (effective) participation • If agreement is not reached, and a decision is to be made

and active involvement in public decision-making. It should without or against the advice of the Indigenous body, this

be measured both by the opportunity to make substantive should be publically disclosed.

(and timely) contributions; and in terms of the effect of the • Regular meetings should occur between government or

contributions on the final decisions made. parliamentary leaders and representatives of the Indigenous

• The rationale for consultation, thus understood, lies in body.

good governance, understood from the perspective of • In the Australian context, it might be useful to establish

both government and governed. Public policy based on a committee of the Senate or of both Houses of the

consultation is likely to be both adequately informed and Commonwealth Parliament, to report on the advice and its

accepted by those to whom they apply. implications for public policy, including legislation.

• Consultation should be undertaken ‘in good faith, with the

objective of reaching agreement.’ These insights suggest the way in which the arrangements should

• The obligation to consult, understood in this way, extends operate in practice. They do not necessarily, however, dictate the

to all public agencies, at all levels of government, exercising scope of the formal obligations to be placed on the Parliament by

public authority through all available instruments, ranging the constitutional provisions.

from legislation, regulations and funding decisions through

to soft law. For reasons suggested earlier, it might be politic for these to be

• The obligation to consult applies when Indigenous interests expressed more narrowly, to formally oblige the Houses of the

are affected ‘directly’, but not in relation to ‘matters of a general Commonwealth Parliament to take account of the Indigenous

nature … assumed to affect the society as a whole’, to quote body’s advice only when a law is made pursuant to the head of

INDIGENOUS LAW BULLETIN July / August, Volume 8, Issue 19 I 21

power that authorises lawmaking, with respect to Indigenous Constitutional Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

Peoples, January 2015.

peoples; or, perhaps, when a law can be characterised as one with

2 Anne Twomey, ‘Putting Words to the Tune of Indigenous

respect to Indigenous peoples, even if it could be supported by Constitutional Recognition’, The Conversation (online), 20 May

another law as well. If this were done, the de facto influence of 2015 <https://theconversation.com/putting-words-to-the-tune-of-

indigenous-constitutional-recognition-42038>.

the body might nevertheless grow over time, through the wider

3 Expert Panel on Constitutional Recognition of Indigenous

range of matters on which it chooses to give advice, the quality of Australians, Recognising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

its advice and the respect that the body attracts. Peoples in the Constitution: Report of the Expert Panel (Report, 16

January 2012).

4 I owe this point to discussions with Michael Crommelin, following

Cheryl Saunders AO is a laureate professor at Melbourne Law the symposium to which these remarks initially were delivered.

School. She has specialist interests in Australian and comparative 5 See, eg, Erna Solberg and Sven-Roald Nystø, Procedures

public law, including comparative constitutional law and method, for Consultation between State Authorities and the Sami

Parliament (Norway) (11 May 2005) National Congress of

intergovernmental relations and constitutional design and change.

Australia’s First Peoples <http://nationalcongress.com.au/

She is a President Emeritus of the International Association of wp-content/uploads/2012/11/ProceduresforConsultationsState-

Constitutional Law, a former President of the International Association AuthoritiesandSami-Parliament.pdf>.

6 Framework Convention on National Minorities, opened for

of Centres for Federal Studies, a former President of the Administrative

signature 1 February 1995, ETS 157 (entered into force 1

Review Council of Australia and a current member of the Advisory February 1998) art 15<http://conventions.coe.int/treaty/en/

Board of International IDEA. Treaties/Html/157.htm>. See also Organization for Security and

Cooperation in Europe, ‘Lund Recommendations on the Effective

Participation of National Minorities in Public Life & Explanatory

This paper was originally presented by Cheryl Saunders at a symposium Note’ (September 1999) 10 [12]–[13] <http://www.osce.org/

hcnm/32240?download=true>.

on constitutional reform at Sydney Law School on 12 June 2015.

7 Ministry of Justice (New Zealand), Guide for Consultation with

Maori (December 1997) <http://www.justice.govt.nz/publications/

1 Cape York Institute, Submission No 38 to the Joint Select publications-archived/1997/guide-for-consultation-with-maori>.

Committee on Constitutional Recognition of Aboriginal and

8 Manitoba Metis Federation Inc v Canada (Attorney-General) [2013]

Torres Strait Islander Peoples, October 2014; Cape York

1 SCR 623.

Institute, Submission No 38.2 to the Joint Select Committee on

Amala Groom

Portrait of a Man, 2015

Type C photograph on Hahnemuhle photo rag paper

5940mm x 8410mm

Image by Liz Warning

22 I INDIGENOUS LAW BULLETIN July / August, Volume 8, Issue 19

You might also like

- External Aids To Interpretation and Construction - Notes of DiscussionDocument12 pagesExternal Aids To Interpretation and Construction - Notes of DiscussionsanchiNo ratings yet

- CopytDocument29 pagesCopytYousuf MohdNo ratings yet

- 051 - Delegated Legislation (465-492)Document28 pages051 - Delegated Legislation (465-492)Karishma RajputNo ratings yet

- 20190427-PRESS RELEASE MR G. H. Schorel-Hlavka O.W.B. ISSUE - Re The Theft of Our Democracy, Etc, & The Constitution-Supplement 46-Shorten-EtcDocument10 pages20190427-PRESS RELEASE MR G. H. Schorel-Hlavka O.W.B. ISSUE - Re The Theft of Our Democracy, Etc, & The Constitution-Supplement 46-Shorten-EtcGerrit Hendrik Schorel-HlavkaNo ratings yet

- 2021 Submission HoR Enquiry Into Constitutional Reform and ReferendumsDocument10 pages2021 Submission HoR Enquiry Into Constitutional Reform and ReferendumsAndrew Francis OliverNo ratings yet

- Elliott Statutoryinterpretationwelfare 1960Document17 pagesElliott Statutoryinterpretationwelfare 1960Kaavya GopalNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law Final Exam NotesDocument21 pagesConstitutional Law Final Exam NotesbriNo ratings yet

- Assignment For BallbDocument5 pagesAssignment For BallbParas SehgalNo ratings yet

- E Mureinik A Bridge To Where - Only Read PG 1-3 and The ConclusionDocument19 pagesE Mureinik A Bridge To Where - Only Read PG 1-3 and The ConclusionZuleika de SouzaNo ratings yet

- Agpalo Notes - Statutory Construction, CH 11Document2 pagesAgpalo Notes - Statutory Construction, CH 11Chikoy AnonuevoNo ratings yet

- Why A Separation of Power in Government Its Importance To ConstitutionalismDocument6 pagesWhy A Separation of Power in Government Its Importance To ConstitutionalismmaccaferriasiaNo ratings yet

- Legal Revision ExamDocument6 pagesLegal Revision ExamSally GuanNo ratings yet

- New Ipr AssignmentDocument5 pagesNew Ipr AssignmentParas SehgalNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Supremacy and Judicial ReasoningDocument20 pagesConstitutional Supremacy and Judicial ReasoningRoberto Javier Oñoro JimenezNo ratings yet

- 2004 Vol4 2pdfDocument25 pages2004 Vol4 2pdfR Nidhi PillayNo ratings yet

- Chapter-III (59-109)Document51 pagesChapter-III (59-109)mNo ratings yet

- Interpretation of StatutesDocument6 pagesInterpretation of StatutesJapneet KaurNo ratings yet

- Gerrit, Have You Got An Issue Against Medical Evacuations?Document4 pagesGerrit, Have You Got An Issue Against Medical Evacuations?Gerrit Hendrik Schorel-HlavkaNo ratings yet

- 1 Blackstone, Commentaries, Vol. I, 160. 2 And, Legally Speaking, of Course, Parliament Can Even Do These Things. 3 Supra, P. 12Document36 pages1 Blackstone, Commentaries, Vol. I, 160. 2 And, Legally Speaking, of Course, Parliament Can Even Do These Things. 3 Supra, P. 12Raquel SantosNo ratings yet

- Against A Written ConstitutionDocument10 pagesAgainst A Written Constitutionvidovdan9852No ratings yet

- Privy CouncilDocument22 pagesPrivy CouncilRahul KanthNo ratings yet

- Law, Politics and Constitutional RightsDocument11 pagesLaw, Politics and Constitutional Rightsmce1000No ratings yet

- Twomey, Anne - The Application of Constitutional Preambles and The Constitutional Recognition of Indigenous AustraliansDocument28 pagesTwomey, Anne - The Application of Constitutional Preambles and The Constitutional Recognition of Indigenous AustraliansRoberto SagredoNo ratings yet

- Mapale Odt PDFDocument15 pagesMapale Odt PDFAndrew SekayiriNo ratings yet

- Sima - Microsoft Word - Federal Constitutional Law Notes - 142 Pages PDFDocument142 pagesSima - Microsoft Word - Federal Constitutional Law Notes - 142 Pages PDFregi.steredNo ratings yet

- Principles of Interpretation of Delegated Legislation - IpleadersDocument9 pagesPrinciples of Interpretation of Delegated Legislation - IpleadersHimanshu BhatiaNo ratings yet

- Separation of PowersDocument9 pagesSeparation of PowersArvindaNo ratings yet

- 130702-Mr G. H. Schorel-Hlavka O.W.B. To Q A Bryce G-G Re Appointment Inter-State CommissionerDocument4 pages130702-Mr G. H. Schorel-Hlavka O.W.B. To Q A Bryce G-G Re Appointment Inter-State CommissionerGerrit Hendrik Schorel-HlavkaNo ratings yet

- Example-Thesis-Proposal MonashDocument9 pagesExample-Thesis-Proposal Monashevasundari100% (1)

- This Content Downloaded From 14.139.214.181 On Fri, 10 Jul 2020 08:06:01 UTCDocument11 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 14.139.214.181 On Fri, 10 Jul 2020 08:06:01 UTCAyush PandeyNo ratings yet

- Delegated Legislation - Unit II PDFDocument110 pagesDelegated Legislation - Unit II PDFsukumarmswNo ratings yet

- Public Law LectureDocument30 pagesPublic Law LectureAra ShuzanNo ratings yet

- 4 PDFDocument15 pages4 PDFAshish SinghNo ratings yet

- A Few Thoughts On The Nexus of Delegated Legislation and Separation of Powers IDocument23 pagesA Few Thoughts On The Nexus of Delegated Legislation and Separation of Powers IabhishekNo ratings yet

- Du Plessis 2000 The Legitimacy of Judicial Review in South Africa S New Constitutional Dispensation Insights From TheDocument15 pagesDu Plessis 2000 The Legitimacy of Judicial Review in South Africa S New Constitutional Dispensation Insights From TheCocobutter VivNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law Notes 1st 2nd SemesterDocument134 pagesConstitutional Law Notes 1st 2nd SemesterKenn Ade100% (2)

- Amending Process of The Indian ConstitutionDocument14 pagesAmending Process of The Indian ConstitutionAadi saklechaNo ratings yet

- SSRN-id2198646 - Características de Las Constituciones EstatalesDocument42 pagesSSRN-id2198646 - Características de Las Constituciones EstatalesLuisa PerezNo ratings yet

- Interpretaion of Statutes 2Document13 pagesInterpretaion of Statutes 2kunalNo ratings yet

- Assignment TopicDocument9 pagesAssignment Topicbabar hayatNo ratings yet

- Reed's Parliamentary Rules: A Manual of General Parliamentary LawFrom EverandReed's Parliamentary Rules: A Manual of General Parliamentary LawNo ratings yet

- Governing Britain: Parliament, ministers and our ambiguous constitutionFrom EverandGoverning Britain: Parliament, ministers and our ambiguous constitutionNo ratings yet

- Law Making ProcessDocument13 pagesLaw Making ProcessUmair Ahmed AndrabiNo ratings yet

- Topic A Lecture 7 - Statute Law Without CasesDocument33 pagesTopic A Lecture 7 - Statute Law Without CasesVasudha BhardwajNo ratings yet

- The Executive Power of The Commonwealth - Peter GerangelosDocument36 pagesThe Executive Power of The Commonwealth - Peter GerangelosUdesh FernandoNo ratings yet

- Sources of Law in BotswanaDocument13 pagesSources of Law in BotswanaTatenda Gwatirisa100% (1)

- National Assembly and Senate Should Take Lead in Protecting The Constitution, Not ViolatingDocument2 pagesNational Assembly and Senate Should Take Lead in Protecting The Constitution, Not ViolatingBevin Bhoke JuniorNo ratings yet

- Commons and The House of Lords - Was Recast in Terms of The Ancient Greek Theory of MixedDocument3 pagesCommons and The House of Lords - Was Recast in Terms of The Ancient Greek Theory of MixedJayson TasarraNo ratings yet

- Consti 1 Syllabus of Atty. Jamon by Alvin C. Rufino PDFDocument38 pagesConsti 1 Syllabus of Atty. Jamon by Alvin C. Rufino PDFReg AnasNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law NCA SummaryDocument59 pagesConstitutional Law NCA SummaryKC Onuigbo100% (11)

- Australian Constitution and Public Law PluralismDocument10 pagesAustralian Constitution and Public Law PluralismCollins Kipkemoi SangNo ratings yet

- LC 1002 - Administrative LawDocument9 pagesLC 1002 - Administrative LawShadab Ahmed AnsariNo ratings yet

- Consti Case NotesDocument11 pagesConsti Case NotesNapoleon Sango IIINo ratings yet

- 07 External AidsDocument29 pages07 External AidsMansi BansodNo ratings yet

- Strathclyde ReviewDocument32 pagesStrathclyde ReviewPoliticsHome.comNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Amendment: Madhav KhoslaDocument17 pagesConstitutional Amendment: Madhav KhoslaAadhitya NarayananNo ratings yet

- K C Wheare Modern Constitutions What A Constitution IsDocument13 pagesK C Wheare Modern Constitutions What A Constitution IsLakshadeep SinghNo ratings yet

- Constitutionalism Additional MaterialDocument23 pagesConstitutionalism Additional MaterialOratile TshenkengNo ratings yet

- Interpretation of Statutes AssignmentDocument17 pagesInterpretation of Statutes AssignmentOwaisWarsiNo ratings yet

- Jessel, Borrero - 2014 - A Laboratory Comparison of Two Variations of Differential-Reinforcement-Of-Low-Rate ProceduresDocument11 pagesJessel, Borrero - 2014 - A Laboratory Comparison of Two Variations of Differential-Reinforcement-Of-Low-Rate ProceduresJohnNo ratings yet

- Singh, Mishra - 2013 - Second Language Proficiency Modulates Conflict-Monitoring in An Oculomotor Stroop Task Evidence From Hindi-EnglisDocument10 pagesSingh, Mishra - 2013 - Second Language Proficiency Modulates Conflict-Monitoring in An Oculomotor Stroop Task Evidence From Hindi-EnglisJohnNo ratings yet

- Lionnet - 1992 - 'Logiques Métisses' Cultural Appropriation and Postcolonial RepresentationsDocument22 pagesLionnet - 1992 - 'Logiques Métisses' Cultural Appropriation and Postcolonial RepresentationsJohnNo ratings yet

- Silverstein - 1976 - EditorialDocument4 pagesSilverstein - 1976 - EditorialJohnNo ratings yet

- Gallegos - 2014 - Paving The Way Indigenous Leaders Creating Change in The Legal WorldDocument11 pagesGallegos - 2014 - Paving The Way Indigenous Leaders Creating Change in The Legal WorldJohnNo ratings yet

- Dequech - 2011 - Uncertainty A Typology and Refinements of Existing Concepts PDFDocument21 pagesDequech - 2011 - Uncertainty A Typology and Refinements of Existing Concepts PDFJohnNo ratings yet

- Dhankar - 2014 - Months in Review March-April PDFDocument1 pageDhankar - 2014 - Months in Review March-April PDFJohnNo ratings yet

- Morschauser - 1987 - Threat Formulae in Ancient EgyptDocument637 pagesMorschauser - 1987 - Threat Formulae in Ancient EgyptJohn100% (1)

- Deshong - 2013 - Indigenous Political Aspirations and The Tides of Change PDFDocument4 pagesDeshong - 2013 - Indigenous Political Aspirations and The Tides of Change PDFJohnNo ratings yet

- Silverstein - 1977 - Homosexuality and The Ethics of Behavioral Intervention. Paper 2Document8 pagesSilverstein - 1977 - Homosexuality and The Ethics of Behavioral Intervention. Paper 2JohnNo ratings yet

- Dews - 1964 - Humors PDFDocument6 pagesDews - 1964 - Humors PDFJohnNo ratings yet

- Cashdan - 1985 - Coping With Risk Reciprocity Among The Basarwa of Northern BotswanaDocument22 pagesCashdan - 1985 - Coping With Risk Reciprocity Among The Basarwa of Northern BotswanaJohnNo ratings yet

- A Student'S Experience As An Aurora Intern: Internships in Native Title LawDocument2 pagesA Student'S Experience As An Aurora Intern: Internships in Native Title LawJohnNo ratings yet

- Amery - 2001 - Language Planning and Language RevivalDocument83 pagesAmery - 2001 - Language Planning and Language RevivalJohnNo ratings yet

- Baer - 1974 - A Note On The Absence of A Santa Claus in Any Known Ecosystem A Rejoinder To WillemsDocument3 pagesBaer - 1974 - A Note On The Absence of A Santa Claus in Any Known Ecosystem A Rejoinder To WillemsJohnNo ratings yet

- Lo Bianco, Slaughter - 2009 - Australian Education Review Second Languages and Australian SchoolingDocument84 pagesLo Bianco, Slaughter - 2009 - Australian Education Review Second Languages and Australian SchoolingJohnNo ratings yet

- Antaki Et Al. - 2003 - Discourse Analysis Means Doing Analysis A Critique of Six Analytic ShortcomingsDocument21 pagesAntaki Et Al. - 2003 - Discourse Analysis Means Doing Analysis A Critique of Six Analytic ShortcomingsJohnNo ratings yet

- Apel, Diller - 2017 - Prison As Punishment A Behavior-Analytic Evaluation of IncarcerationDocument14 pagesApel, Diller - 2017 - Prison As Punishment A Behavior-Analytic Evaluation of IncarcerationJohnNo ratings yet

- Zuberbu - 2005 - The Phylogenetic Roots of Language Evidence From Primate Communication and CognitionDocument5 pagesZuberbu - 2005 - The Phylogenetic Roots of Language Evidence From Primate Communication and CognitionJohnNo ratings yet

- Lejano - 2012 - Parâmetros para Análise de Políticas - A Fusão de Texto e ContextoDocument293 pagesLejano - 2012 - Parâmetros para Análise de Políticas - A Fusão de Texto e ContextoJohn67% (3)

- Amery - 2004 - Early Christian Missionaries Preserving or Destroying Indigenous Languages and CultureDocument36 pagesAmery - 2004 - Early Christian Missionaries Preserving or Destroying Indigenous Languages and CultureJohnNo ratings yet

- Coupland, Holmes, Coupland - 1998 - Negotiating Sun Use Constructing Consistency and Managing Inconsistency PDFDocument23 pagesCoupland, Holmes, Coupland - 1998 - Negotiating Sun Use Constructing Consistency and Managing Inconsistency PDFJohnNo ratings yet

- Amery - 2010 - Monitoring The Use of KaurnaDocument11 pagesAmery - 2010 - Monitoring The Use of KaurnaJohnNo ratings yet

- Thompson - 2015 - Artist Statement Christian ThompsonDocument1 pageThompson - 2015 - Artist Statement Christian ThompsonJohnNo ratings yet

- Romaine - 2006 - Planning For The Survival of Linguistic Diversity PDFDocument33 pagesRomaine - 2006 - Planning For The Survival of Linguistic Diversity PDFJohnNo ratings yet

- Does Reconciliation Require A Treaty? 2014Document3 pagesDoes Reconciliation Require A Treaty? 2014JohnNo ratings yet

- Heads or Tails Two Sides of The Coin 1986Document21 pagesHeads or Tails Two Sides of The Coin 1986JohnNo ratings yet

- Adams, Towns, Gavey - 1995 - Dominance and Entitlement The Rhetoric Men Use To Discuss Their Violence Towards WomenDocument21 pagesAdams, Towns, Gavey - 1995 - Dominance and Entitlement The Rhetoric Men Use To Discuss Their Violence Towards WomenJohnNo ratings yet

- Sally Wiggins - 2002 - Talking With Your Mouth Full Gustatory 'MMMS' and The Embodiment of PleasureDocument28 pagesSally Wiggins - 2002 - Talking With Your Mouth Full Gustatory 'MMMS' and The Embodiment of PleasureJohnNo ratings yet

- Counter Aff Anthony DoqueDocument3 pagesCounter Aff Anthony DoqueApril Legaspi Fernandez100% (1)

- Panlilio v. RTCDocument1 pagePanlilio v. RTCJohney DoeNo ratings yet

- Clinton v. Jones - Case Brief For Law Students - Casebriefs PDFDocument4 pagesClinton v. Jones - Case Brief For Law Students - Casebriefs PDFEu CaNo ratings yet

- Jakim Bey Affivadit of Truth and InvestigationDocument13 pagesJakim Bey Affivadit of Truth and Investigationjakim el bey100% (1)

- Renegotiating Intimacies: Marriage, Sexualities, Living Practices (II)Document3 pagesRenegotiating Intimacies: Marriage, Sexualities, Living Practices (II)api-25886263No ratings yet

- Affidavit of Corporate DenialDocument9 pagesAffidavit of Corporate DenialHOPE6578% (9)

- Solid Manila Corporation Vs Bio Hong TradingDocument3 pagesSolid Manila Corporation Vs Bio Hong TradingJethroNo ratings yet

- Case DigestDocument7 pagesCase DigestSachuzen23No ratings yet

- El Chapo Trial Witness Colombian Drug Lord "Chupeta" Agreed To Forfeit 10BDocument9 pagesEl Chapo Trial Witness Colombian Drug Lord "Chupeta" Agreed To Forfeit 10BChivis MartinezNo ratings yet

- Status Review Sample Los Angeles DcfsDocument18 pagesStatus Review Sample Los Angeles DcfsSusyBonillaNo ratings yet

- Emergency MotionDocument7 pagesEmergency MotionmikekvolpeNo ratings yet

- Maharashtra Marine Fishing Regulation Act, 1981Document13 pagesMaharashtra Marine Fishing Regulation Act, 1981Latest Laws TeamNo ratings yet

- Glossary of Legal (And Related) Terms Courthouse Signs English-SpanishDocument31 pagesGlossary of Legal (And Related) Terms Courthouse Signs English-SpanishJasna PeraltaNo ratings yet

- Petition For Certiorari SampleDocument35 pagesPetition For Certiorari SampleGerard Nelson Manalo100% (1)

- AffidavitDocument2 pagesAffidavitAngel Ann CañaNo ratings yet

- Corruption (EngDocument8 pagesCorruption (EngFasih RehmanNo ratings yet

- AGSABA BQsDocument2 pagesAGSABA BQsJake AriñoNo ratings yet

- Monthly Accomplishment Report (Ndep) A.Y. 2018-2019 Urbiztondo National High SchoolDocument1 pageMonthly Accomplishment Report (Ndep) A.Y. 2018-2019 Urbiztondo National High SchoolBon FreecsNo ratings yet

- Appellate JurisdictionDocument28 pagesAppellate JurisdictionMuHAMMAD Ziya ul haqq Quraishy100% (1)

- Coja Vs CADocument2 pagesCoja Vs CAanamergal100% (1)

- BAPMI Rules On ArbitratorsDocument5 pagesBAPMI Rules On Arbitratorsedwina_kharismaNo ratings yet

- Richard Greenle v. United States Postal Service, 46 F.3d 1151, 10th Cir. (1995)Document2 pagesRichard Greenle v. United States Postal Service, 46 F.3d 1151, 10th Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Elizalde Rope Factory, Inc. vs. Court of Industrial RelationsDocument6 pagesElizalde Rope Factory, Inc. vs. Court of Industrial RelationsAnonymous WDEHEGxDhNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 153254 September 30, 2004 People of The Philippines, Appellee, EDEN DEL CASTILLO, AppellantDocument10 pagesG.R. No. 153254 September 30, 2004 People of The Philippines, Appellee, EDEN DEL CASTILLO, AppellantgirlNo ratings yet

- Contract Law-Study MaterialDocument349 pagesContract Law-Study Materialvimalmakadia73% (11)

- Raul Balog Compra JRDocument8 pagesRaul Balog Compra JRMarkyholicz AmpilNo ratings yet

- Petition To Connecticut Supreme CourtDocument9 pagesPetition To Connecticut Supreme CourtJosephine MillerNo ratings yet

- Environmental Quality (Prescribed Premises Scheduled Wastes Treatment and Disposal Facilities) (Amendment) Regulations 2006 - P.U. (A) 253-2006 PDFDocument2 pagesEnvironmental Quality (Prescribed Premises Scheduled Wastes Treatment and Disposal Facilities) (Amendment) Regulations 2006 - P.U. (A) 253-2006 PDFVan PijeNo ratings yet

- Chapter - Ii General Conditions of ServiceDocument7 pagesChapter - Ii General Conditions of ServiceAMAN JHANo ratings yet