Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Primer On Social Discount Rates

Uploaded by

Ruth ChiahOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Primer On Social Discount Rates

Uploaded by

Ruth ChiahCopyright:

Available Formats

Economics in policy-making 5

Discounting and

time preferences

Cost–benefit analysis (CBA), social CBA and Social Return on Investment (SROI)

do not simply involve listing the costs and benefits of a project over time and adding

them up. They also involve considering how much the future impacts of a project are

worth to us now – which is often a very different matter.

What is discounting? The extent to which future cash flows are devalued is

determined through the discount rate. To illustrate how

Broadly speaking, welfare economics works on the this works, imagine a hypothetical investment which

rule that individuals have a higher ‘time preference’ for involves a cost of £50 today (input) and generates a

the present than for the future. That is, people prefer to benefit of £100 three years from now (output in year 3).

increase their “utility” (their welfare) sooner rather than

later. Ask yourself, for instance, if you’d rather have £100 Table 1 (on the next page) shows how manipulating the

now or in a year’s time? discount rate affects the PV of that future £100 return.

Most people’s answer to this question would be ‘now’ – Net Present Value (NPV) represents the net benefits

unless there was some extra benefit gained by waiting. of the project, after weighing up the PV of its costs

For instance, would you consider accepting the money and benefits – i.e. its discounted benefits minus its

in one years’ time if it meant you would be given more? discounted costs.

How much more would make it worth the wait?

Given that, in this example, the £50 costs of the project are

All this points to the idea that the ‘present value’ (PV) of borne today (in year zero); they are not influenced by the

things (i.e. the value you put on them now) increases or future discount rate. The £100 worth of benefits, however,

decreases depending on how soon they will happen. are influenced by the discount rate – since they arise after

three years. So the overall NPV of the transaction depends

In order to take this into account, CBA involves the on the level at which this discount rate is set.

practice of discounting – which means devaluing future

benefits and costs so as to represent their present value As Table 1 shows, setting a 0% discount rate is the same

(PV). It is this present value of costs and benefits that as stating no time preference for the present. The costs

CBA weighs up and presents so that decision-makers incurred today would be weighted the same as benefits

can determine whether a project or intervention should accruing three years from now. So the present value of

go ahead. Only when the present value (PV) of benefit the future £100 cash flow would not be discounted, and

outweighs the present value (PV) of costs should an the NPV of making the original £50 transaction would be

action be taken. £50 (£100−£50).

Published by nef (the new economics foundation), April 2013 as part of the MSEP project to build the socio-economic capacity of marine NGOs.

www.neweconomics.org Tel: 020 7820 6300 Email: chris.williams@neweconomics.org Registered charity number 1055254.

Briefing 5: Discounting and time preferences

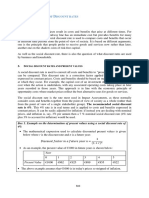

Table 1: A discount rate application example

Year 0 Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 NPV 0% discount NPV 5% discount NPV 15% discount

(now) (t = 1) (t = 2) (t = 3) rate (£) rate (£) rate (£)

Costs £50 0 0 0

£50 (£100-£50) £36.38 (£86.38-£50) £15.75 (£65.75-£50)

Benefits 0 0 0 £100

By discounting future values by 5% per year, however, collective choice (i.e. capable of accurately foreseeing

then the present value of gaining £100 cash three years future public needs) or should the State impose time

in the future would work out at £86.38. This, in turn, preferences?

would place the net present value of paying £50 today at

roughly £36.38. Two contrasting views on these issues are salient:

Finally, if applying a 15% discount rate to the transaction, 1. On the one hand, a variety of mainstream economists

the present value of future benefits would almost halve consider that what is valid for individuals (i.e. relatively

to £65.75 So the net present value (net benefit) will, in strong preference for the present) is also valid for

this case, be only £15.75 (£65.75–£50). society as a whole.

As you can see from the examples above, the choice of According to this view, so-called “social” discount

discount rate can critically influence the results of a cost- rates (i.e. discounting used for appraising public

benefit analysis. The higher the discount rate, the higher investment) should definitely be used, and should

the presumed time preference for immediate costs be based upon individual preferences (i.e. collective

and benefits, and the lower the value placed on future preferences are perceived as the aggregation of

benefits and costs. individual / private preferences).

In the example above we went from a net present value This view takes an empirical, rather than normative

(NPV) of £50 to ~£16 simply by raising the discount stance. That is, instead of asking whether we should

rate to 15%. So you can see that, if the discount rate discount, it asserts (in a “consequentialist” rationale)

went above 20% (stating a very high time preference for that because private individuals discount the future,

the present) the net benefits (NPV) of the project would we should also discount for public investment.

come out as zero or even a negative number. Such a

result would imply that the initial investment is a bad, 2. Other scholars think that the question of discounting

inefficient idea that should be abandoned. public investment is an essentially philosophical one,

relating to how much a given society should value the

future (including the well-being of future generations)

Should we use discounting for social and public

relative to the present. According to this stream of

interventions?

thought, social discount rates cannot be based on

There is wide consensus that discounting makes sense the evidently high time preferences of individuals, and

at a personal / household level, because people do tend should be set sensibly lower. There is also evidence

to have a higher preference for well-being in the present that individuals are very bad at computing time for

rather than in the future. This is partly caused by fear of example, which makes the focus on ‘time preferences’

not being alive in the future to collect those well-being paradoxical.

benefits. As such, we should expect discount rates at

this micro level to be virtually always higher than zero. In practice, discount rates for social projects and public

(Although the fact that people usually care about their interventions are set differently in different countries.

children’s future wellbeing can lower such discount rates, Despite the debate outlined above, many countries

and partly explain why individuals tend to save money opt to set their public discount rates lower than private

and assets). discount rates (as illustrated below). As you can see

below, there is a trend towards using lower discount

Likewise if conducting a CBA for a private investment, rates for public interventions.

discounting is sensible and can be set relatively

high, depending on a variety of factors and the time The UK requires all social projects’ costs and benefits

preferences of the entrepreneurs in question. to be discounted at a rate of 3.5% per year – except for

projects happening 30 years or more into the future,

But when it comes to public investment the matter is not for which lower discount rates are chosen (see section

so clear. Should we discount the future when carrying below for an explanation).

out CBA’s of public interventions, when doing so would

clearly favour short-term gains rather than public interest Of course, a government’s decisions to impose specific

in the long-run? Or, is there a rate at which a society discount rates are not without criticism. Aside from the

as a whole is willing to sacrifice current consumption or general lack of consensus on the matter, discounting

well-being in exchange for future consumption and well- the future has numerous implications – particularly for

being? Finally, are individuals capable of making this environmental sustainability.

2 Briefing 5: Discounting and time preferences

Country/Agency Discount Rate

Imagine a situation whereby action could be taken to

restore a particular fish stock. A £200 million investment

Australia 8% (1991): rate annually reviewed is required today in order to stop the stock being fished

to extinction over the next fifty years. (This investment

Canada 10%

might include compensation for fishermen in return for

People’s Republic 8% of short and medium term projects; not fishing the endangered species, or, funding to allow

of China lower than 8% rate for long-term the fisherman to re-train and take up other professions).

projects

France Real discount rate set since 1960; After fifty years of protection, the replenished fish

set at 8% in 1985 and 4% in 2005 population is predicted to be worth £1 billion in actual

market value – five times the value of our original £200

Germany 1999: 4% million investment.

2004: 3%

India 12% But, if the UK’s prevailing social discount rate of 3.5%

was applied, that £1 billion benefit, due 50 years down

Italy 5% the line, would generate a present value of just £179

New Zealand 10% as a standard rate whenever there million1 And – given this amount is less than the £200

(Treasury) is no other agreed sector discount rate million cost of the project – the investment would not be

made.

Norway 1978: 7%

1998: 3.5% As you can see, a high discount rate can be a major

Pakistan 12%

impediment when it comes to making our economic

system more environmentally sustainable. It can also

Philippines 15% devalue the well-being of future generations, which is

Spain 6% for transport; 4% for water

ethically questionable. Can we really suggest, for example,

that a coral reef is “worth” less to a person fifty years into

United Kingdom 1967: 8% the future than to a person living today?

1969: 10%

1978: 5%

What are the alternatives to future discounting?

1989: 6%

2003: 3.5% One way of tackling this problem of inter-generational bias

Different rates lower than 3.5% for is to reject future discounting. This would mean that costs

long-term projects over 30 years and benefits accruing to present generations would be

considered equal to those accruing to future generations.

Beyond ethical discussions, a 0% discount rate could

What are the implications of discounting

have the perverse effect of favouring over-investment in

the future?

the present (to mitigate higher costs in the future) and

The debate about discounting the future in public thus spur further environmental and natural resource

investment has been accentuated by environmental degradation. The perversity is that this would enhance

problems like biodiversity loss, ecosystem disruption and what “0%” discount rate proponents aim to avoid: the

climate change. All of these problems are bound to have reduction of the stock of natural capital available to future

long-term impacts which will affect us, as well as future generations.

generations.

TEEB (The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity)

By and large, public investment for mitigating these has proposed a solution to this problem by suggesting

impacts and preventing further environmental that different social discount rates should be used for

destruction is considered necessary for the well-being different purposes. A 0% discount rate could be used

of future generations. But how much should our current for investment in environmental sustainability only, while

generation invest? Should we sacrifice part of our higher discount rates would be used for other forms of

well-being for the benefit of future generations? This is public investment. This proposal avoids the problems

dependent, among other things, on the inter-temporal associated with using a zero discount rate (see the first

preferences (and thus discounting of public investment) point above).

of the current generation.

Finally, other research has suggested a so-called

If we choose to discount investments in biodiversity “hyperbolic” discount rate. The discount rate would be

conservation and climate change mitigation, the benefits high for short term impacts, in order to represent the

that our investments deliver for future generations will time preferences of the current generation (for their own

automatically appear smaller in present value terms. This income stream), but would gradually decrease over time

would foster a state of “low inter-generational equity”, to enhance inter-generational equity. Put simply, medium

where the wellbeing of different generations – including to long-term impacts would be discounted less than

those yet to be born – would be unequally valued. short-term impacts.

3 Briefing 5: Discounting and time preferences

Further reading and useful resources Economics in Policy-making

briefings:

TEEB: Discounting, ethics, and options for

maintaining biodiversity and ecosystem integrity 1 An overview of economics

http://evolution.binghamton.edu/evos/wp-content/ Sagar Shah

uploads/2010/01/Gowdy-2009.aspx.pdf 2 How economics is used in government

decision-making

Climate Change and Discounting the Future: A

Susan Steed

Guide for the Perplexed

http://www.hks.harvard.edu/m-rcbg/cepr/Online%20 3 Valuing the environment in economic terms

Library/Papers/Weisbach_Sunstein_Climate_Future. Olivier Vardakoulias

4 Social CBA and SROI

Olivier Vardakoulias

Asian Development Bank: Review of theory and

practice of discounting 5 Discounting and time preferences

http://www2.adb.org/Documents/ERD/Working_ Olivier Vardakoulias

Papers/WP094.pdf

6 Multi-criteria analysis

Olivier Vardakoulias

Valuing future life and future lives: A framework for

understanding discounting 7 Beyond GDP: Valuing what matters and

http://faculty.som.yale.edu/ShaneFrederick/ measuring natural capital

Future%20Life%20and%20Future%20Lives.pdf Saamah Abdallah

8 Markets, market failure, and regulation

James Meadway

9a Finance and money: the basics

The Marine Socio–Economics Project (MSEP) Josh Ryan-Collins

is a project funded by The Tubney Charitable Trust

and coordinated by nef in partnership with the 9b What’s wrong with our financial system?

WWF, MCS, RSPB and The Wildlife Trusts. Josh Ryan-Collins

10 Property rights and ownership models

The project aims to build socio-economic capacity James Meadway

and cooperation between NGOs and aid their

engagement with all sectors using the marine 11 Behavioural economics – dispelling the myths

environment. Susan Steed

Note: A ‘’discount factor’’ is the amount by which

any future value must be multiplied to convert it

into present value

= 1 / (1+DR) ^ t

1 i.e. 1billion / (1 + 0.035) ^ 50 (1 billion, divided by 3.5% to the power of 50 years) = 179,053,337.

Written by: Olivier Vardakoulias

Edited by: Chris Williams

Design by: the Argument by Design – www.tabd.co.uk

Published by nef (the new economics foundation), April 2013 as part of the MSEProject to build the socio-economic capacity of marine NGOs.

www.neweconomics.org Tel: 020 7820 6300 Email: chris.williams@neweconomics.org Registered charity number 1055254.

4 Briefing 5: Discounting and time preferences

You might also like

- An MBA in a Book: Everything You Need to Know to Master Business - In One Book!From EverandAn MBA in a Book: Everything You Need to Know to Master Business - In One Book!No ratings yet

- Cost-Benefit AnalysisDocument47 pagesCost-Benefit AnalysisDarryl LemNo ratings yet

- Home Gym: Workout at Home for Beginners, Workout Kit & AccessoriesFrom EverandHome Gym: Workout at Home for Beginners, Workout Kit & AccessoriesNo ratings yet

- WK 9 Tutorial 10 Suggested AnswersDocument7 pagesWK 9 Tutorial 10 Suggested Answerswen niNo ratings yet

- Efficient Ways to Maintain Your Finances: Budgeting, Retirement Plan, Passive Income & Personal FinanceFrom EverandEfficient Ways to Maintain Your Finances: Budgeting, Retirement Plan, Passive Income & Personal FinanceNo ratings yet

- Public Finance Notes On Chapter 8Document3 pagesPublic Finance Notes On Chapter 8Colin SealeNo ratings yet

- Solutions Manual To Accompany Cost Benefit Analysis 4th Edition 0137002696Document10 pagesSolutions Manual To Accompany Cost Benefit Analysis 4th Edition 0137002696CrystalDavisntgrw100% (89)

- What Is The Investment MultiplierDocument4 pagesWhat Is The Investment MultiplierArpita DasNo ratings yet

- Discount RatesDocument14 pagesDiscount RatesAditya Kumar SinghNo ratings yet

- Tool #61. The Use of Discount RatesDocument5 pagesTool #61. The Use of Discount RatesRodolfo TupayachiNo ratings yet

- Ebook Cost Benefit Analysis 4Th Edition Boardman Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument36 pagesEbook Cost Benefit Analysis 4Th Edition Boardman Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFCherylHorngjmf100% (10)

- School of LawDocument4 pagesSchool of LawSri MuganNo ratings yet

- Econ311: Public Finance Policy and Practice, Lecture Notes 2013 Public Expenditure Appraisal Project AppraisalDocument21 pagesEcon311: Public Finance Policy and Practice, Lecture Notes 2013 Public Expenditure Appraisal Project AppraisalTinotenda MuzavaziNo ratings yet

- Financial - Management Book of Paramasivam and SubramaniamDocument21 pagesFinancial - Management Book of Paramasivam and SubramaniamPandy PeriasamyNo ratings yet

- Income and ExpenditureDocument5 pagesIncome and Expendituremusinguzi francisNo ratings yet

- Sequence 5 - Life Cycle Costing - Engineering EconomicsDocument30 pagesSequence 5 - Life Cycle Costing - Engineering EconomicsZeeshan AhmadNo ratings yet

- IGNOU MEC-002 Free Solved Assignment 2012Document8 pagesIGNOU MEC-002 Free Solved Assignment 2012manish.cdmaNo ratings yet

- Unit - Iii - Cost Benefit Analysis For Building & Infrastructure Projects-Sara5401Document42 pagesUnit - Iii - Cost Benefit Analysis For Building & Infrastructure Projects-Sara5401Thamil macNo ratings yet

- Investment Multiplier - EconomicsDocument5 pagesInvestment Multiplier - Economicsanon_357116694100% (1)

- Behavioural Economics Intertemporal ChoiceDocument3 pagesBehavioural Economics Intertemporal Choiceanne1708No ratings yet

- Time Value of MoneyDocument7 pagesTime Value of Moneyanand.arora7No ratings yet

- Discounting Explainer - FinalDocument5 pagesDiscounting Explainer - FinalAhsanNo ratings yet

- PV PrimerDocument15 pagesPV Primerveda20No ratings yet

- Relationship Between GDP, Consumption, Savings and InvestmentDocument16 pagesRelationship Between GDP, Consumption, Savings and InvestmentBharath NaikNo ratings yet

- An Overview of BenefitDocument9 pagesAn Overview of BenefitDivyashri JainNo ratings yet

- Exam 4Document13 pagesExam 4Faheem ManzoorNo ratings yet

- Investment DecisionDocument26 pagesInvestment DecisionToyin Gabriel AyelemiNo ratings yet

- Boardman Im ch5Document9 pagesBoardman Im ch5Efraín Jesús Márquez Flores0% (1)

- 10 Things You Should Know About EconomicsDocument16 pages10 Things You Should Know About EconomicsLine RingcodanNo ratings yet

- 304A Financial Management and Decision MakingDocument67 pages304A Financial Management and Decision MakingSam SamNo ratings yet

- IGNOU MEC-002 Free Solved Assignment 2012Document8 pagesIGNOU MEC-002 Free Solved Assignment 2012manuraj4No ratings yet

- Understanding The Time Value of MoneyDocument5 pagesUnderstanding The Time Value of MoneyMARL VINCENT L LABITADNo ratings yet

- Taxes On Savings: Jonathan Gruber Public Finance and Public PolicyDocument51 pagesTaxes On Savings: Jonathan Gruber Public Finance and Public PolicyGaluh WicaksanaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 3Document13 pagesLecture 3ashrrakat31No ratings yet

- 03 - Time Value of MoneyDocument32 pages03 - Time Value of Moneyusman jamalNo ratings yet

- San José State UniversityDocument18 pagesSan José State UniversityDivyashri JainNo ratings yet

- Time Value of MoneyDocument36 pagesTime Value of MoneyAkeef KhanNo ratings yet

- Cap 5Document21 pagesCap 5IvanaNo ratings yet

- Solution Manual For Macroeconomics 15th Canadian Edition Campbell R Mcconnell Stanley L Brue Sean Masaki Flynn Tom BarbieroDocument17 pagesSolution Manual For Macroeconomics 15th Canadian Edition Campbell R Mcconnell Stanley L Brue Sean Masaki Flynn Tom Barbierothomaslucasikwjeqyonm100% (24)

- Chapter 1-Practice - SolutionDocument18 pagesChapter 1-Practice - SolutionXpertZ Pro 1No ratings yet

- Consumption SavingsDocument68 pagesConsumption SavingskhatedeleonNo ratings yet

- 10 Principles of EconomicsDocument12 pages10 Principles of EconomicsAbdul Rehman AhmadNo ratings yet

- Ques No 1.briefly Explain and Illustrate The Concept of Time Value of MoneyDocument15 pagesQues No 1.briefly Explain and Illustrate The Concept of Time Value of MoneyIstiaque AhmedNo ratings yet

- Steps of CostDocument5 pagesSteps of Costleonxchima SmogNo ratings yet

- Macro 2006Document296 pagesMacro 2006api-3819060No ratings yet

- Time Value of MoneyDocument7 pagesTime Value of MoneyRishab Jain 2027203No ratings yet

- Redefining The Optimal Retirement Income StrategyDocument13 pagesRedefining The Optimal Retirement Income StrategyidiotNo ratings yet

- Economics As An Applied ScienceDocument35 pagesEconomics As An Applied ScienceStephanie Ann MARIDABLENo ratings yet

- Unit - Vi Energy Economic Analysis: Energy Auditing & Demand Side ManagementDocument18 pagesUnit - Vi Energy Economic Analysis: Energy Auditing & Demand Side ManagementDIVYA PRASOONA CNo ratings yet

- DEFLATIONDocument4 pagesDEFLATIONTanshit SarmadiNo ratings yet

- ECO209 Macroeconomic Theory: Consumption and SavingDocument5 pagesECO209 Macroeconomic Theory: Consumption and SavingKiranNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Cost Benefit AnalysisDocument15 pagesAn Introduction To Cost Benefit Analysisasrar121No ratings yet

- Accounting ExplainedDocument69 pagesAccounting ExplainedGeetaNo ratings yet

- TMVTBDocument17 pagesTMVTBShantam RajanNo ratings yet

- Keynes ProfPigouMoney 1937Document12 pagesKeynes ProfPigouMoney 1937Jorge “Pollux” MedranoNo ratings yet

- Financial Management: Chapter Three Time Value of MoneyDocument16 pagesFinancial Management: Chapter Three Time Value of MoneyLydiaNo ratings yet

- Consumption and SavingDocument6 pagesConsumption and Savingmah rukhNo ratings yet

- No 06. Chapter 4: Consumption, Saving, and InvestmentDocument35 pagesNo 06. Chapter 4: Consumption, Saving, and InvestmentBushra NaumanNo ratings yet

- Module 3 - Project Documentation and SelectionDocument5 pagesModule 3 - Project Documentation and SelectionJohncel TawatNo ratings yet

- Capital Expenditure AnalysisDocument5 pagesCapital Expenditure AnalysisAllan SsemujjuNo ratings yet

- Managerial Economics Applications Strategies and Tactics 14th Edition Mcguigan Solutions ManualDocument26 pagesManagerial Economics Applications Strategies and Tactics 14th Edition Mcguigan Solutions ManualGeraldWalkerajqr100% (57)

- Aviation Investment Economic Appraisal For Airports - Air Traffic Management - Airlines and AeronauticsDocument259 pagesAviation Investment Economic Appraisal For Airports - Air Traffic Management - Airlines and AeronauticsDipendra ShresthaNo ratings yet

- LCOE CalculationDocument27 pagesLCOE CalculationRadhakrishnan VNo ratings yet

- Sustainable DesignDocument48 pagesSustainable DesignAbdul Hakkim100% (2)

- Sustanable DevelopmentDocument10 pagesSustanable Developmentsushant dawaneNo ratings yet

- Discounting Slides (Feb 10, 2022)Document19 pagesDiscounting Slides (Feb 10, 2022)H MNo ratings yet

- Analisis Costo BeneficioDocument9 pagesAnalisis Costo BeneficioSTEVAN BELLO GUTIERREZNo ratings yet

- Unesco - Eolss Sample Chapter: On The Economics of Non-Renewable ResourcesDocument27 pagesUnesco - Eolss Sample Chapter: On The Economics of Non-Renewable ResourcesKartik MaulekhiNo ratings yet

- Frederick - Cognitive Reflection and Decision MakingDocument156 pagesFrederick - Cognitive Reflection and Decision MakingirmNo ratings yet

- Whole-Life Costing AnalysisDocument64 pagesWhole-Life Costing Analysisernest kusiimaNo ratings yet

- The Implications of Hyperbolic Discounting: For Project EvaluationDocument18 pagesThe Implications of Hyperbolic Discounting: For Project EvaluationRodolfo QuijadaNo ratings yet

- Copenhagen Consensus 2008 YoheDocument52 pagesCopenhagen Consensus 2008 YoheANDI Agencia de Noticias do Direito da Infancia100% (1)

- OMB Circular A4 Comment LetterDocument13 pagesOMB Circular A4 Comment LetterEzra HercykNo ratings yet

- Automobile Externalities and PoliciesDocument28 pagesAutomobile Externalities and Policiescamila adhaniaNo ratings yet

- Defrancesco E., Gatto P., Rosato P., (2014) A 'Component-Based' Approach To Discounting For Nature Resource Damage Assesment PDFDocument9 pagesDefrancesco E., Gatto P., Rosato P., (2014) A 'Component-Based' Approach To Discounting For Nature Resource Damage Assesment PDFChechoReyesNo ratings yet

- Dasgupta Review - Full ReportDocument606 pagesDasgupta Review - Full ReportanfezaNo ratings yet

- Nature in Economics: Partha DasguptaDocument8 pagesNature in Economics: Partha DasguptaOssi OllinahoNo ratings yet

- Lecture Notes: Discounting and Climate Change: 1 Components of The Discount RateDocument11 pagesLecture Notes: Discounting and Climate Change: 1 Components of The Discount RateRicardo Machuca BreñaNo ratings yet

- Ethics Review of Carbon TaxesDocument31 pagesEthics Review of Carbon TaxesBách Nguyễn XuânNo ratings yet

- The Economic Effects of Climate ChangeDocument24 pagesThe Economic Effects of Climate ChangeMartin BarragánNo ratings yet

- CU/CUF Amicus Brief - Louisiana v. Biden (Biden Climate Executive Order)Document36 pagesCU/CUF Amicus Brief - Louisiana v. Biden (Biden Climate Executive Order)Citizens UnitedNo ratings yet

- Discount Rate - Environmental EconomicsDocument6 pagesDiscount Rate - Environmental EconomicsRoberta DGNo ratings yet

- Full Download Managerial Economics Applications Strategies and Tactics 13th Edition Mcguigan Solutions ManualDocument36 pagesFull Download Managerial Economics Applications Strategies and Tactics 13th Edition Mcguigan Solutions Manualthuyradzavichzuk100% (29)

- Cowen & Parfit - Against The Social Discount RateDocument13 pagesCowen & Parfit - Against The Social Discount RateWazavNo ratings yet

- A Manual For The Economic Evaluation of Energy EffDocument121 pagesA Manual For The Economic Evaluation of Energy Effwalqui1No ratings yet

- Arrow Et. Al. - 2004Document34 pagesArrow Et. Al. - 2004Ayush KumarNo ratings yet

- Manual For Procurement of PPPs 2022 Clean v10 (Draft)Document86 pagesManual For Procurement of PPPs 2022 Clean v10 (Draft)Yogesh Sindhu100% (1)

- Full Download Managerial Economics Applications Strategies and Tactics 14th Edition Mcguigan Solutions ManualDocument36 pagesFull Download Managerial Economics Applications Strategies and Tactics 14th Edition Mcguigan Solutions Manualthuyradzavichzuk100% (38)